Network Accountability in Healthcare: A Perspective from a First Nations Community in Canada*

Accepted by Merridee Bujaki and Leslie Berger. This article is dedicated to Uche Ezike-Dennis: gone too soon, but forever in our hearts.

ABSTRACT

enThis study examines the role of accountability in the governance and delivery of healthcare to a First Nations community in Canada. Drawing on actor network theory, this study explores the role of accountability in the formation and sustenance of a healthcare network using the case study of a First Nations healthcare organization. The study provides insights into how accountability helps to sustain a network of actors with divergent interests and a plurality of strategies. It finds that network accountability is the central mechanism that motivates the principal actors in the network to reconstitute themselves and converge around the purpose of strengthening governance. This study also finds evidence of accountability as a multidimensional construct that facilitates the sustenance of the federal government as the controlling actor in the network. This study provides fresh empirical insights gained from a flesh-and-blood, actual network that acknowledges the context of a marginalized group—namely, First Nations peoples. Furthermore, this study extends and presents a viable accountability model that can be adopted as the federal government enters into self-governance agreements with First Nations peoples. In contrast to the dominant literature on accountability, this study adopts the unique context of a marginalized group in a market-based developed economy.

RÉSUMÉ

frResponsabilisation du réseau dans le domaine des soins de santé : perspective issue d’une communauté des Premières Nations au Canada

La présente étude se penche sur le rôle de la responsabilisation dans la gouvernance et la prestation des soins de santé à une communauté des Premières Nations au Canada. S’appuyant sur la théorie de l’acteur-réseau, elle explore le rôle joué par la responsabilisation dans la création et le maintien d’un réseau de soins de santé à l’aide d’une étude de cas portant sur un organisme de soins de santé des Premières Nations. L’étude propose des observations sur la façon dont la responsabilisation favorise le maintien d’un réseau d’acteurs qui ont des intérêts divergents et font appel à diverses stratégies. Elle établit que la responsabilisation du réseau est le mécanisme central qui motive les principaux acteurs du réseau à se mobiliser et à unir leurs forces pour renforcer la gouvernance. Elle fait aussi état d’éléments probants indiquant que la responsabilité est un concept multidimensionnel qui contribue à maintenir le gouvernement fédéral comme acteur dominant dans le réseau. Elle fournit des perspectives empiriques inédites provenant d’un réseau réel actif sur le terrain qui reconnaît la situation d’un groupe marginalisé – soit les peuples des Premières Nations. En outre, elle élargit et présente un modèle de responsabilisation viable qui peut être adopté dans le contexte actuel où le gouvernement fédéral conclut des ententes d’auto-gouvernance avec les Premières Nations. Contrairement aux recherches qu’on retrouve dans la littérature dominante sur la comptabilité, cette étude adopte le point de vue unique d’un groupe marginalisé dans une économie de marché.

INTRODUCTION

This field-level study examines the role of accountability in the governance and delivery of healthcare to a First Nations community in Canada (hereafter, the Band). In Canada, the term “First Nations” refers to a segment of Indigenous Peoples (Younging 2018), with the other segments being the Inuit and the Métis. Therefore, the Band we study is appropriately characterized as both First Nations and Indigenous. In this study, we use the term “First Nations” except where the terms “Indian” or “Aboriginal” are used in a specific context, such as in legislation, research, or colonial-era literature. This study responds to the call by Mutiganda (2013) for further empirical studies on how policies intersect with accountability. He writes, “The relational aspect of accountability implies a hierarchical relationship between the giver of accounts, that is, the accountee, and the receiver of those accounts, or the accountor” (Mutiganda 2013, 520).

Generally, the accountability literature is dominated by hierarchical forms of accountability (Cooper and Owen 2007; Joannides 2012; Modell 2009; Mutiganda 2013). Roberts (1991) challenges this status quo by introducing socializing accountability while acknowledging that the dominant form of accountability is hierarchical. The hierarchical form of accountability is also referred to as “upward” (Christensen and Ebrahim 2006; Fowler and Cordery 2015) or “vertical” (O'Donnell 1999). This is because one actor is often able to exercise power over the other (Mitchell et al. 1997). The alternate form is referred to as “lateral” (Christensen and Ebrahim 2006; Fowler and Cordery 2015) or “horizontal” (O'Donnell 1999). This study relies on O'Donnell's (1999) framework, which focuses on the accountability of political institutions. The framework is relevant because the Band health center is accountable to two political institutions—the Canadian federal government, through the Ministry of Health's (Health Canada) First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB), and the Band administration, which is governed by a chief and other council members, who are referred to collectively as the “Chief-and-Council.”

Some First Nations peoples in Canada have signed agreements, known as treaties, with the Government of Canada, which define the rights and obligations of the parties. Specifically, the treaties provide for self-governance rights and political recognition for First Nations Band administrations. Consequently, while some First Nations communities, including the Band we investigated, use democratic systems to elect the Chief-and-Council, others recognize hereditary Chiefs. Given this dual political structure, this study investigates the form of accountability that sustains the network alliance. Furthermore, although the treaties recognize the political self-governance of First Nations, social services, such as healthcare, are funded and governed by Canada's federal and provincial governments, creating further tensions. Some First Nations communities manage their own programs; in other instances, the programs are comanaged or even managed by third parties, depending on the state of past governance practices of the particular First Nations community. When we use the term government in this study, we refer to the Canadian federal government; we specify provincial government when appropriate, and we use “Band administration” or “Chief-and-Council” to refer to First Nations government.

Another commonality of the aforementioned studies is that they have primarily investigated accountability in Western contexts, which may explain the common discoveries of the dominant hierarchical forms of accountability. Of the studies undertaken in alternate contexts, some have sought to investigate the federal government's approach to First Nations governance and uncovered mechanisms of gradual program devolution by government to First Nations, including capacity building to eventually transition full responsibility for governance to First Nations peoples (Baker and Schneider 2015; Baker et al. 2012; Rae 2009). Other studies have contributed to the debate on First Nations self-governance (Baker and Schneider 2015; Baker et al. 2012; Shepherd 2006). However, few studies, if any, have sought to empirically investigate the role of accountability in healthcare governance from the perspectives of First Nations peoples. We aim to fill this research gap. It is important to conduct this study because, in Canada, despite similar per capita spending, First Nations communities often experience subpar health outcomes, including higher rates of HIV, diabetes, and infant and maternal mortality, compared to their non-Indigenous counterparts. Worse still, it has been suggested in the media that Canadian First Nations experience “third world” conditions (Levasseur and Marcoux 2015). Thus, the debate about First Nations healthcare no longer revolves around whether inequities exist but instead usually focuses on amelioration (Health Canada 2003).

In summary, the purposes of this study are twofold. First, we draw on actor network theory (ANT) (Callon 1986; Latour 1987; Law 1986, 1992) to explore the role played by accountability in the formation and sustenance of a healthcare network that includes multiple political institutions—the Chief-and-Council, the federal government, and various actors, such as First Nations patients and employees, federal government health employees, and all their repertories. We conceptualize this actor network as neither a hierarchy nor a market healthcare alliance (Powell 1990), but rather a network of actants (human and nonhuman actors) whose relationships are continually redefined. Previous studies have shown that tensions exist and will always exist in actor networks (Briers and Chua 2001; Chua 1995; Jorgensen and Messner 2010). The tensions in the First Nations healthcare network are caused by the existence of two political institutions and further exacerbated by the competing interests of these political institutions as they battle for control of the network. In this study, we refer to the role they compete for as the “Actor-in-Chief” and refer to the role of the First Nations health employees charged with accountability (accountees) as “Custodians.” The Custodians are all Indigenous employees of the Band health center. Relatedly, we examine the accountability relationship in the First Nations context as a nonhierarchical construct. While prior studies (e.g., Bruijn and Whiteman 2010; Crawley and Sinclair 2003; Lertzman and Vredenburg 2005) rely on Roberts's (1991) notion of “socialized accountability” to present evidence on various actor network issues, the current study provides empirical evidence of a nonhierarchical and multidimensional approach to accountability. Prior to colonialism, Indigenous leaders were chosen through either hereditary or traditional/cultural procedures. However, the Indian Act of 1876 provided for the election of Band administrations, paving the way for political gaming. The Custodians aver that cultural abuse and financial abuse are inextricably linked, with cases of individuals who were not knowledgeable about First Nations culture seeking leadership positions as Indigenous elders and then committing financial improprieties. Consequently, the Custodians act as nodes to enforce accountability of network actors, including political actors. They are also able to institute a network form of accountability (Klijn and Koppenjan 2014)—specifically, by bringing other actors, such as doctors not captured under the traditional accountability relationship, into the framework and seeking to hold them accountable.

Second, we investigate if and how one political institution is subjugated and the other political institution emerges as a controlling actor. ANT suggests that networks are defined by tensions, and at the center of these tensions are relationships between actors, especially between actors seeking to exercise control over the network. These relationships occupy a single genre—namely, “trials of strength” in which “no actant eclipses another a priori without further effort” (Harman 2009, 25). We investigate the problematization of the network—the framing of the network's problems by the controlling actor in order to recruit allies—and we also investigate the financial and behavioral controls that are deployed to sustain control. We find that the federal government successfully problematized the network's challenges as caused by systematic abuse.

This study contributes to the accountability literature by providing empirical evidence from a First Nations setting in which issues of accountability mobilize diverse actors in the healthcare network to converge around the common purpose of curtailing financial abuse. Our study also extends the accountability bodies of work by providing an understanding of the role of accountability in the translation, retranslation, and sustenance of a network of actors with competing interests and a plurality of overarching strategies. Specifically, we find that First Nations actors, who were previously subordinated in power relations, are capable of exercising power by enforcing network accountability. This study is also relevant for management practice, because understanding how the network is sustained is critical to improving healthcare outcomes in Canada, a country where healthcare is regarded as both a right and a defining characteristic of Canadian identity, with 64% of Canadians citing the Canadian healthcare system as a source of national pride (Statistics Canada 2013). The reminder of the paper is organized as follows. First, we discuss the background and related accountability literature on First Nations healthcare in Canada and our site of investigation. Next, we advance the theoretical framework and methodology for the study. Then, we present the findings and discuss the study results, and lastly, we conclude.

BACKGROUND

Accountability

In the accountability literature, Sinclair (1995) identifies five forms of accountability: political, public, managerial, professional, and personal. Political accountability is either vertical (Bovens et al. 1998; O'Donnell 1999), which encompasses, for example, the use of elections to hold political actors responsible, or horizontal (Bovens 2007; O'Donnell 1999), which relies on strong institutions to hold political actors (e.g., the executive branch) accountable. As O'Donnell (1999, 39) argues, “For this horizontal form of accountability to be effective there must exist state agencies that are authorized and willing to oversee, control, redress and/or sanction unlawful actions of other state agencies.” In other words, the superordinate resolution mechanism for political forms of accountability is a strong legal framework. Political accountability is also two-dimensional and incorporates answerability and enforcement. Answerability refers to the obligation of political actors to explain their actions, while enforcement refers to the ability of accountability agencies to impose sanctions on political actors (Schedler 1999, 14).

Mutiganda (2013) discusses accountability between budgetary actors where the political actors demand accounts (accountor) and the technical actors give accounts (accountee), implying a hierarchical relationship. As Mutiganda (2013, 526) further notes, political and technical accountability actors' institutionalized “ways of thinking and doing are less similar in the realm of action.” Joannides (2012) also proposes hierarchical forms of accountability and further argues that accountability be framed as the giving and demanding of reasons for conduct akin to answerability.

Roberts (1991, 363) identifies an alternate form of “socializing accountability” that exists within organizations: “Socializing forms of accountability suggested that there exists the possibility of a different experience of self and one's relation to others. . . . Out of such relationships is built mutual understanding and ties of friendship, loyalty, and reciprocal obligation.” Our study contributes to the accountability literature by uncovering within the First Nations healthcare setting some themes commonly used in hierarchical accountability. Specifically, this study identifies the Custodians as accountees and the FNIHB, in its capacity as funder, as an upward stakeholder. This study also extends the accountability literature by providing empirical evidence of the Custodians' perceptions of accountability as multidimensional, with political actors (both the federal government and the Chief-and-Council) sometimes also needing to answer to technical actors. While the purpose of political accountability is to enforce legality, in the case of network accountability it enforces the purpose that has been bestowed on the network, usually by the controlling actor and negotiated with network allies.

First Nations Healthcare in Canada

Despite consensus on the need for quality healthcare for First Nations peoples, the two political institutions of the Canadian government and the Chief-and-Council have joint responsibility but divergent strategies for First Nations healthcare. We argue that the First Nations healthcare network is neither hierarchical nor market-based because there is no strict command structure between the two political actors, and their participation in the network does not depend on market forces. Moreover, differences between the political institutions cannot be addressed by meta-rationality (Jorgensen and Messner 2010)—the prioritization of a superordinate goal to which both groups subscribe and are subordinated. For instance, although Health Canada, as the sole funder, is an upward stakeholder, the communities are not answerable to this ministry in the same way that a company's marketing and sales teams are answerable to the company's president in an organizational hierarchy. This is because, although healthcare is provided to First Nations as a matter of policy in Canada, the federal government assumes the obligation to deliver these services and cannot arbitrarily decide to pull funding for First Nations health projects or overtly use funding as a means of social control, as was the case with rations in the 1800s that were withheld from First Nations as a means of extracting compliance (Waldram et al. 1997). Likewise, the communities require funding and cannot arbitrarily walk away from funding arrangements.

Although the Canadian healthcare system is befitting that of an OECD country, the country's First Nations population has less access to healthcare and poorer or subpar health status and outcomes than the country's non-Indigenous population (Coburn and Eakin 1998; D'Arcy 1998; Waldram et al. 1997). The dichotomies in healthcare have led to charges of neglect, indifference, and even genocide against the Canadian federal government (Waldram et al. 1997). This contradiction in the accessibility and equality of healthcare is acknowledged by the Canadian government. In fact, the Indian Health Policy of 1979 (Health Canada 2007) uses such phrases as “grave” and “intolerably low” to describe the state of First Nations healthcare. According to the Office of the Auditor General of Canada (n.d.), “Health Canada had not implemented its objective of ensuring that First Nations individuals living in remote communities have comparable access to clinical and client care services as other provincial residents living in similar geographic locations.”

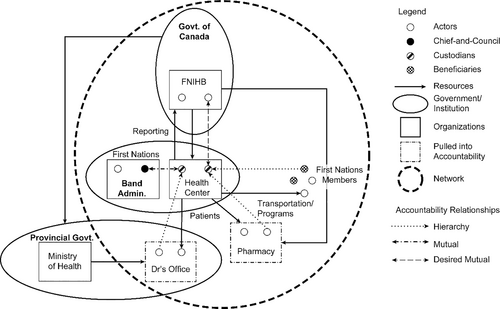

In Canada, provincial governments are responsible for providing and cofunding healthcare for residents, except for First Nations peoples and members of the military, whose healthcare is primarily funded by the federal government (Canada Health Act 1985). Figure 1 presents a high-level illustration of the First Nations healthcare network and funding flows, showing how the federal government cofunds healthcare in provinces through Canada Health Transfers, the fiscal mechanism by which the federal government cofunds its share of healthcare. The political institutions of the Government of Canada, the provincial government, and the Band administration are shown in Figure 1. The Government of Canada agency responsible for First Nations health programs on reserves is the FNIHB, which provides health coverage through the Non-Insured Health Benefits (NIHB) program, such as medical transportation, drugs, dental care, vision care, medical supplies and equipment, short-term crisis intervention mental health counseling, and ancillary health services, to First Nations and Inuit people when they are not covered by other provincial insurance (Government of Canada 2017). The responsibility for defining programming and funding means that the FNIHB provides governance for First Nations healthcare, while Indigenous employees manage individual health centers that provide community care on reserves. Where there is no attendant general practitioner at the health center, such as our site of investigation, patients are transported to the nearest city for primary and specialist care. Medical transportation personnel deal with the logistics of getting First Nations patients to hospitals via air or ground transportation. Consequently, the medical transportation unit, which accounted for roughly 56% of the health center budget, is the busiest program and is a key element of this study.

There were 634 First Nations communities in Canada with a population of 1,008,955 people as at December 30, 2019, representing approximately 3% of the Canadian population, of whom approximately 40% live on reserves (Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada 2020; Government of Canada 2020). In 2018–2019, federal government health spending on First Nations and Inuit healthcare was 2.3% of Canada's total healthcare spending (Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer 2021). The site of investigation is one of many First Nations health centers in Canada responsible for administering the Government of Canada's programs on the reserve (the Band).

We consider this Band a suitable case study to investigate network accountability dynamics, because the FNIHB placed it under comanagement and required improved accountability before it would return to self-management. Bands can either self-manage their health centers or, where accountability is a concern, they can be comanaged or turned over to third-party management. The latter two forms of management require participating in a remedial management plan before the Band can return to self-management. The Band fell into comanagement amid allegations of financial mismanagement by the Chief-and-Council. According to one Custodian, this situation occurred during a transition from an era of “true elders” to a new kind of Chief-and-Council. Consequently, the Band provides a suitable site for the empirical investigation of the role played by accountability in improving and fulfilling governance obligations between the actors in the network in several ways. First, examining a Band that is in comanagement could provide relevant evidence for other Bands in similar comanagement scenarios. Second, examining a Band in comanagement might provide relevant findings for other First Nations communities, given broader public policy discussions about accountability mechanisms, as all programs (including healthcare) are set to be transitioned to the First Nations under a self-governance framework, as embodied in the landmark Métis First Nations self-governance agreement with Canada.1

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

We conceptualize the delivery of healthcare to First Nations communities and the various actors involved as constituting a network. This network constitutes of actants—namely, non-Indigenous Health Canada employees, First Nations health employees, and repertoires available to both groups of actors, including systems, policies, budgets, and reports. We rely primarily on ANT (Callon 1986; Latour 1987) to understand the formation of the network and ensuing relational tensions. The framework of ANT and, specifically, the sociology of translation, facilitate our understanding of the issues presented in this study. ANT moves away from explaining social relationships in terms of micro- and macro-phenomena. As Latour (1999) explains, social scientists start by inquiring into face-to-face interactions at local sites, only to realize that many of the elements necessary to understand the situation are embodied in culture, norms, values, structure, social context, nonlocal actors, and so on. Once the scientists arrive at this macro level, dissatisfaction leads them to move back to the original flesh-and-blood network in a perpetually circular fashion (Latour 1999).

We recognize that “a wide number of organizations (and individuals) are affected by an organization, even if the stakeholders are not funders, but receivers or suppliers of goods and services” (Fowler and Cordery 2015, 131). Cooper and Owen (2007, 665) argue that the funder (in our study, the Canadian government) aims to enforce “one-dimensional” stakeholder accountability, with the Custodians as the accountable party in that model. The funder (or controlling actor) aims to attain control by financial and behavioral means. In this study, the Custodians sought to reframe accountability as multidimensional and become the nodes in the network that strive to enforce accountability between all the stakeholders, whether institutions or actors. Stakeholders include suppliers, such as doctors, who are not ordinarily contemplated in the traditional First Nations healthcare accountor–accountee relationship; political institutions, such as the funding stakeholder FNIHB and the First Nations government (Chief-and-Council); and First Nation actors—that is, healthcare beneficiaries and employees of the health center.

Consistent with Modell (2009), we adopt ANT as an alternate lens through which to understand the role of the actors in individual organizations rather than populations of organizations in institutional fields. The relationships in the network are not just inter- or intra-organizational. While we focus on the accountability relationship between the individual actors, we acknowledge the reporting relationship between the FNIHB and the health center, and we treat the Custodians in the health center as the nexus for accountability relationships between several stakeholders. Although the primary tension is the result of a battle for control between the Chief-and-Council and the federal government, our study finds that the external actors may also contribute to the tensions in the network.

Actors seeking control will recruit others to their purpose through problematization, which is a time-driven phase of framing the problems in the network. Problematization occurs when an actor seeks to become indispensable to the other actors by defining their problems and proposing that the problems are best resolved if the actors collectively negotiate an obligatory passage point (Callon 1986). The obligatory passage point is the mechanism—in this case, accountability—that causes the actors to mobilize and converge around the purpose of strengthening governance.

METHODOLOGY

Given the peculiar context of First Nations healthcare, our investigation was well served by a case study approach, which allowed us delve into their real-world context in great depth. The appropriateness of case studies in contextually oriented situations, such as First Nations, is aptly described by Alam et al. (2004, 139): “Case studies are considered appropriate where issues under investigation are unique and particular, and emphasis is on understanding, interpretation and explanation.”

Our data collection primarily relied on interviews with First Nations employees in the health center who were directly subject to the accountor–accountee relationship, as evidenced by their provision of periodic program reporting to the FNIHB. Furthermore, the first researcher spent extensive time in the field with First Nations actors and observed how healthcare is motivated, discussed, and delivered on a Canadian reserve. The study is limited by the number of health centers we investigated and the number of interviewees. Furthermore, our site of investigation might not be representative of all First Nations. However, all the First Nation health centers are governed by similar contracts, known as contribution agreements, and similar accountability frameworks; as such, our study provides insights that are likely relevant for other Indigenous settings (and non-Indigenous settings with a similar social context—for example, community health centers, subaltern societies, and the global South), especially for Bands in comanagement and those facing political accountability issues. Consequently, we traded breadth (number of Bands, health centers, or participants) for depth (one health center in great depth) to uncover rich insights with broad implications. Denzin (1978) proposes various approaches to triangulation, such as multiple observers, theories, methods, and data sources. We relied on data source triangulation (Denzin 1978, 101) by “go[ing] to as many concrete situations as possible in forming the observational base.” Specifically, we sought to interview stakeholders with differing organizational views on accountability and individuals in different organizational functions while also relying on other sources, such as contribution agreements. This allowed for multiple perspectives but also gave us a means of validating our findings, as we focused on common themes across interviews and documents.

The interviews were complemented by reviews of two kinds of data: documents in the public domain and proprietary data not available in the public domain. Our interview data were the primary form of evidence used in our analysis. However, these two additional kinds of documents, along with extant literature, were used primarily to corroborate (or otherwise) interview data. Proprietary documents include the health center's periodic reporting to the FNIHB, and documents in the public domain include the Indian Health Policy of 1979, the Auditor General of Canada's reports, government websites (e.g., Health Canada, Indigenous Affairs), Health Canada benefits documentation, program reports, Health Co-management Committee meeting minutes, and Government of Canada Strategic Plans.

Our institutions' guidelines on ethics review conform to the Canadian Tri-Council Policy Statement on Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans, including chapter 9, which deals specifically with research involving First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples of Canada (Government of Canada 2018). While our participants all provided informed consent, including by confirming their willingness to be audio-recorded and quoted, our research design opted for anonymizing the specific details of the Band and the functional titles of the participants, given the candid nature of their participation in this study. The rich nature of the insights provided prompted the need to take additional precautions to protect their identities.

We interviewed four participants, three of whom worked for the health center, and one who was a program manager for the FNIHB. The three health organization participants represented 100% of the NIHB accountees in the healthcare center. The fourth participant was a regional manager (a non-Indigenous person); we chose to speak to this person given the responsibilities of the position, which essentially placed the manager at the front line of dealing with First Nations communities in terms of accountability and overall compliance. However, only quotations from the First Nations participants are included in the findings, as we sought to illuminate the First Nations perspective on accountability in this study. Our interviews with First Nations participants captured the views of individuals involved in organizational levels of accountability. These Custodians were all Indigenous members of the Band, by birth or marriage, who worked at the health center. They constitute the frontline of accountability for the community's healthcare organization. We gathered information on the respondents' work and life on the reserve, reporting obligations, and their interactions with accounting practices and other actors in the healthcare space.

Every interview was recorded and later transcribed. Each interview lasted between 30 minutes and 2 hours, and each participant was interviewed twice. After transcription, the data were selectively coded using NVivo software and then examined and reduced to data with theoretical relevance. Using NVivo, we assigned first cycle codes, which include budget, audit, reporting, accountability, micromanagement, program manager, Health Canada, doctor, medical transportation system, and benefit coverage. We then abstracted common themes and interpreted our data using ANT to arrive at the following three themes: (i) performativity and controls, (ii) network accountability, and (iii) translated network. This approach is consistent with Yin's (2014) approach of examining theoretical propositions, creating a description, using a mixture of qualitative interview data, and examining rival theories. Specifically, we used an iterative process (Yin 2014) of checking, comparing, and theorizing against archival data and literature. Finally, we utilized the interview data in our findings, as in vivo texts (direct quotations) and abstractions after applying theoretical insights to our data.

FINDINGS AND ANALYSIS

Performativity and Controls

They think that I'm the one that's making all the rules. I'm not. I'm just the messenger. They don't understand that.

This role as a messenger implies a somewhat hierarchical relationship between accountee and accountor, which is expected given that the Canadian government as the funder has the traits of an upward stakeholder, demanding a one-dimensional accountability relationship. Messengers are “emissaries” in ANT parlance. ANT requires that emissaries be both mobile and durable. While the Custodians are mobile, they partly rely on systems to achieve durability.

The FNIHB attains control by enlisting other actors as allies or, as Law (1986, 255) describes, “Machines or other physical objects, and people, sometimes separately but more frequently in combination . . . seem to be the obvious raw materials for the actor who seeks to control others.” Our study reveals that these “raw materials” include the Mobile Transportation System (MTS) reporting software, used for making and tracking appointments. In the MTS, people who missed appointments—“no shows”—are tracked and a note is entered into the system, requiring them to make up for missed appointments. In other words, the system creates a type of blacklist. Other raw material includes flex budgets, notice of budget adjustment, healthcare policies, financial policies (e.g., the separation of finances by having the health center operate a separate bank account), and the entire repertoire used by the health organization and Health Canada's FNIHB staff. These raw materials are described in ANT as inscriptions that are “durable and mobile emissaries” (Law 1986) and are used to instill certain behaviors. Therefore, the controlling actors' power is not a result of some inherent strength but rather of their alliances with human and nonhuman agents of control—for all intents and purposes, an actor is its relationships with others (Harman 2009, 17).

In this case study, an analysis of policy and program reporting documentation reveals two main forms of controls: financial and behavioral. Financial controls were required to ensure accountability of upward stakeholders (Band council), and behavioral controls were required to ensure the downward accountability of beneficiaries (patients and employees). Health Canada puts these controls in place at the health center to enable the Custodians to enforce accountability of all actors in the network. These two forms of control are described in detail in the following subsections.

Financial Controls

Say that HRD [Human Resources Development, a non-health center department] is short [of] funds to pay their payroll or something. They [Chief-and-Council] were borrowing from Health [Center] dollars to pay for them. But their money is quarterly, so they only get a lump sum every few months. So, when that money would come in, it would be spent already, so they couldn't pay back health. It's like borrowing from Peter to pay Paul but you can't pay Peter back.

I got an earful from the Chief yesterday because the Chief only hears one side: “We're not giving him enough money.”

Now, with the way the Chief-and-Councils have come into place and how they mismanaged dollars over the last 20 . . . at least the last 20 years, 15 years, since those elders have moved on and passed on, a new kind of Chief-and-Council came into place, and now it's how . . . we used to be in a position of providing a service to the people. As leadership, they were providing a service to the people. Now, they switched it around where people are a service to them [are servicing them].

The leadership at the time was very accountable. They made sure that people did their jobs. The generation that I had supervise me, they were very powerful supervisors because they are the ones who could speak all three languages, and they were accountable. You got to work. You walked in the door. If you were after 8:00 in the morning, you were sent home. They don't do that anymore because they don't have that generation now overseeing them. We learned to be accountable back then to our jobs and what we do and how we proceed.

That, to me, is the biggest disgrace because you have not grown up in it. You haven't practiced it. You haven't lived it, and then you create this image of what you think it looks like. You pretend you know the ceremonies and the songs, and you start preaching to the younger generation, and it's all a lie. To me, that's the ultimate disgrace.

The sacrifice is physical, emotional, mental, spiritual, and it's done during that time of this family, and you have ceremonies before you get to that main one in the summer time.

We vote them in, and they put themselves in that position. “While I'm your employer, I can get rid of you.”

The health center was funded by the Government of Canada but was responsible to the First Nations political institution. As such, while the Government of Canada is an upward stakeholder, which implies hierarchical accountability, the competing obligation to the Chief-and-Council complicated the First Nations healthcare accountability framework (see Figure 1). To exercise control, it was not sufficient to be the funder, since the Government of Canada could not withdraw funding if the Custodians aligned with the Chief-and-Council rather than the federal government. Rather, the shared view that there was rampant abuse of healthcare was successfully problematized by Health Canada and is evident in the language used in FNIHB documentation on benefits eligibility. In sharp contrast to the documentation for non-First Nations people, we observed that over the period of our field work, Health Canada, in policy guidelines on the FNIHB website,2 mentioned several abuses that would result in First Nations peoples losing their healthcare benefits, highlighting an a priori assumption on the part of the Canadian government that abuse of benefits was a problem in First Nations healthcare.

Comanagement made that biggest change because Health Canada—and we were concerned about our credibility in our position and jobs and programming and dollars and how we couldn't get things done. Now that we have comanagement in place, and Health Canada has put that into an actual agreement, as part of our agreement to have a comanager to structure how things need to go with no political influence anymore, because that was the problem. Now, we are standing on our two feet somewhat, still getting there and making decisions based on what we have and not what we have not.

Okay, what are the issues that we are needing to fix here? Number one, our financial accountability. Our bank transfers were back and forth every month between the Band and Health, Band and Health, like they would borrow, put back, borrow, put back.

So, from [New Bank], I determine our salary and then we move that into [Old Bank], but we only do monthly, weekly.

We only do that, like I said biweekly, because we don't want Chief-and-Council to actually see how much we have with our working budget.

The payroll policy in question allowed the Custodians to use a non-Band-controlled account at New Bank for the payroll to prevent the Chief-and-Council from being able to access these funds. The separation of funds was a financial control mechanism used to minimize the quantum of potential losses, and these financial controls were intended primarily to curtail abuse.

Behavioral Controls

Now we started putting boundaries around that, time clock, accountability, and so it just took layers of improving things from the basic.

We have our Band policy, our Band employee policy that we follow. And also, Health has . . . we each have our own program policies that we have to follow. Shit comes with every job you have. For my program, that usually happens a lot because I have to follow my policy.

At the end of the month, we batch. If that file is incomplete [in the MTS system] and it says that the client didn't go, then Health Canada will [mark it as a] no-show. We can't provide services for that client until they've gone and made up for that trip and brought back some type of confirmation that they went on their own. So, when I get that back, I have to fax it off to Health Canada to prove that the client did go on their own and make up for that trip. Then they remove that. A lot of them would get upset with me, because they think that it's me that's doing that, but it's not.

When the community don't like you, we [Government] know that you're doing a good job. I was like, well, I'm not the best. I'm not popular out here.

“Well, that's a white man's way”—that's what I get from them [beneficiaries]. I said, “No.” In my mind, it's a respect, it's accountability, and it's being proud because your word means everything.

The participant's use of the “white man's way” is a reference to colonial ways, and evidence, in their view, that the government has extended the hierarchy of accountability relationship beyond the formal accountees (Custodians) to patients and other stakeholders on the reserves, through the Custodians. This positioning of actors relative to others in the network is known as performativity in the network, a necessary step in translation.

Thus, accounting inscriptions (behavioral controls) were used to modify behavior and to make accountability in healthcare more effective, from the perspective of the Custodians, than in Band programs that were funded by other government agencies. In other words, the Custodians used accounting inscriptions to resolve tensions in the network and hold other actors accountable. Although accounting was intended to serve the needs of Health Canada as the controlling actor, it also empowered the Custodians in their roles.

Network Accountability

Health Canada, too, needs to be accountable to what they say and do because it affects how I react or not react.

This desire for mutual monitoring confirms that while the Custodians held their community members and Chiefs accountable, they also believed that the government should be held accountable for program outcomes. If a government directive was going to negatively impact patients, the Custodian would be willing to counteract that directive, as it would mean holding the government accountable, in the Custodian's view. However, in reality, the formal accountability structure remains hierarchical, while functioning like a mutual relationship, given the formality of the contribution agreements and the power the government wields as an upward stakeholder, such as the decision whether a Band should be under third-party management or comanagement. While this mutual form of accountability has some similarities with horizontal accountability, it is also quite different. For example, horizontal accountability depends on strong institutions and a legal framework for enforcement (Schedler 1999), while the mutual form of social accountability is based on discretion and relationships (Roberts 1991)—a network form of accountability.

The nearest doctor, who out here people call the Candyman, is only 15 minutes away and he is going to give you whatever you ask for. It's not what you need. It's what you want. That's what he will give you.

That's too bad that's how he operates. It's too bad that it's mostly my people, the Native community, that are his clientele. He is not helping a situation. He's just helping the addiction and that's sad. It's very, very sad.

They're the ones that are there to give us the information and to hear out our problems that we're having. Our head office knew that this is what's been happening for a few years.

I had to make changes there too because I had some doctors who were abusing the system and abusing my clients and providing prescription drugs and getting them dependent on them.

He's been over-prescribing. I don't know how he does that. . . . We stopped transporting there.

We started using what power we realized we had through Health Canada because Health Canada was saying, “If you don't want to transport, don't transport.” We thought it was mandatory all the time. Now we realized, no, we can put our own guidelines around what that means.

In the absence of the government holding this doctor accountable and sanctioning him, the Custodians took charge of holding him accountable by quoting policy and refusing to transport patients to his clinic, in the process reframing the network accountability relationship as multidimensional. There was really no basis in law; the Custodians did not have formal institutional support for nontransportation, but they had the relationships to enforce network accountability. This modified accountability framework was enacted in the network structure in response to unethical behavior by other actors, even if these actors were ordinarily considered to be outside of the accountor–accountee framework and were pulled into the accountability framework, such as doctors and pharmacies (Figure 1). Ordinarily the provincial ministry or department of health or the respective college (of physicians or pharmacists) would be responsible for ensuring the accountability of these professionals. In this case, however, the Custodians sought to hold these actors accountable, which effectively made the Custodians the nodes for enforcing network accountability.

A Translated Network

We're dealing with all issues with the past financial person, the past Chief, the past director. There were all these problems that were created financially accountability-wise, work-wise, program, everything.

Now I report to a comanager and we work together, because her role is to help me understand managerial stuff, being accountable. Because I come from a place of empathy from counseling, and sometimes, you have to be able just to call a spade a spade and all that stuff.

Whereas, 20 years ago when things weren't done properly, it could go. But now it can't, because document program, reporting documentation has changed considerably.

Now they are making sure that the dollars they are sending out to us for health is being carried out by someone who is certified to do it, who was accountable to do it and could manage it. That's what's happening slowly, which is a good thing. It just goes back to being proud of what you do and being accountable.

They [Health Canada] are the ones who are insisting we be accountable, and we're saying yes, we are.

It's gotten stricter. . . . [W]e can't be doing that today. So that part has changed a lot, which is good because now you're accountable to your job. You're accountable for your funding, and you're holding the community accountable to be responsible for themselves.

We are now in the middle of change and fact-finding and looking for where did those dollars go? Who accounted for it? Then, we had a ministerial audit done for that year, and so they came in, did a nitty-gritty ministerial audit, which was really good. I liked that because it really showed where things fell, and that has to do with receipts, program dollars. We don't know if they were actually spent on what was said it was going to be spent on because we never got receipts. The people identified are the most problematic staff.

We're in that place now of getting staff account[able] and accredited, and that way, they can fall back on the ethics and principles, the vision, the mission. They can fall back on something that says, “This is why I'm here.”

We're slowly moving away to following our actual employee policies and having a legal stand.

If somebody actually sued them as an individual, that would change everything really fast. But there are only a handful of us who know that. The rest of the community don't know that.

He is abusive verbally. All the women would cringe and not do anything, but we're the power here.

They don't read the agreement. We know that because you can pull things over their eyes and throw back why we have to be accountable because they haven't read the agreement. If they did, they would not be at our door like today asking us for this and that. Because if they read the agreement and they signed it, they would know that they're accountable to make sure the dollars are used for what they're meant to be used for.

The Chief-and-Council's continual failure to “mobilize” allies has resulted in Health Canada intervening and framing the problems as abuse, which has resonated with the Custodians and helped to mobilize them as federal government allies. The Custodians, while welcoming this role, found that the specific form of accountor–accountee relationship intended for the network was insufficient and modified it to achieve network accountability, one in which the political institutions (the government and the Chief-and-Council, denoted in Figure 1) and suppliers (doctors and pharmacists, shown as “pulled into accountability” in Figure 1) needed to be just as accountable as patients, health center employees, and the Custodians themselves, who hitherto had been the primary, if not sole, subjects of the traditional accountability framework.

DISCUSSION

Cooper and Owen (2007) argue that the government makes use of one-dimensional power in a quest for hierarchical accountability. This approach “ignores key issues such the establishment of rights and transfer of power to stakeholder groups” (Cooper and Owen 2007, 665). In our study, accountability was used to reframe the Custodians' responsibilities, and they extended the accountability relationship to the users of healthcare. In other words, the Custodians would be accountable to the FNIHB, and the First Nations users of healthcare would be accountable to the Custodians. Furthermore, the Custodians acted as the nexus for this network form of accountability. Specifically, they brought other stakeholders who were not contemplated in an accountor–accountee relationship into their accountability framework. They also aimed to make the accountability relationship with FNIHB reciprocal.

I know I can't explain that to the chief the way he needs to hear it because he's got an audience of the other council, if he barks at you, he makes himself feel good, so I let him bark. That's all he could do anyway.

The Custodians relying on financial controls clearly recognize that they can exert power over the Chief. On the surface, it appears that financial controls should have been enough to incentivize the Custodians' adherence to the upward stakeholder—the FNIHB. However, as argued, although the financial controls were an enabler, they were insufficient. The mere fact that the FNIHB is the health organization's financier did not necessarily mobilize actors to Health Canada's purpose, nor was the threat of program cancellation sufficient to achieve control in the actor network, especially because there was no precedent for program cancellation.

As such, the installation of Health Canada as the controlling actor was possible only with the support of Custodians. The government's empowerment and mobilization of Custodians as allies alter their position relative to other First Nations actors. The Custodians perceived comanagement as a positive, mutually reinforcing relationship, especially because it helped the Band to avoid third-party management and a total loss of autonomy, and it curtailed the Band administration's misuse of health center resources. Furthermore, while under the current leadership, autonomy has resulted in financial abuse and poor health outcomes, improving accountability would put the Band on the path back to self-managing its health programs, which is a necessary step toward eventual First Nations self-governance. The Custodians used their knowledge to further achieve a level of empowerment based on their relations with other actors, including the federal government and First Nations actors. As these changes take form, accountability starts to force the actors to assume relative positions. For example, the Custodians redefined accountability as multidimensional and argued that government and other external actors that exert significant impacts on the health organization's operations and budgets should also be held accountable.

CONCLUSION

This study examines the role of accountability in the governance and delivery of healthcare to a First Nations community in Canada. It attempts to capture and contextualize the essence of the engagement between diverse actors in the First Nations healthcare network. Using a case study method, this study provides insights about the nature, context, and complexity of the social well-being of a marginalized group of the Canadian population. We contribute to the accountability literature by using ANT to unpack the role that accountability plays in translating a network full of tensions. Specifically, we find that accountability forces the network actors to converge on a purpose—that is, strengthening governance. The study is limited in that we were able to access only one site of investigation, but this shortcoming was mitigated by data source triangulation and the fact that First Nations health centers are governed by similar contribution agreements, depending on their funding models. Another limitation is that we include only the perspectives of First Nations participants, because we seek to illuminate the Indigenous perspective on accountability. The addition of non–First Nations participants might have presented a more inclusive account of accountability but would likely have conformed to the dominant hierarchical views on accountability. We call for further empirical research (including of other First Nations) that investigates the network form of accountability and deepens understanding of other contexts that may be more (or less) effective than traditional notions of accountability.

The study finds that the interpretations and effects of accountability cause tensions among the network of actors involved in First Nations healthcare governance and delivery. We find that this First Nations community regards an accountability framework that holds all actors in a network—whether political (the government and the Chief-and-Council) or external (doctors)—to the same ethical standards of a multidimensional, nonhierarchical accountability framework to be more suitable than traditional notions of accountor–accountee accountability demanded by upward stakeholders. Simply put, an accountability relationship that perpetually subjects First Nations employees to the giving of accounts, reporting, or justifying, without a reciprocal accounting by the government on how it is meeting the healthcare needs of the First Nations community, is regarded as inappropriate. This finding is supported by prior studies (Lertzman and Vredenburg 2005) that find there is an ethical need to engage with First Nations peoples in accordance with their wishes and other studies (Baker et al. 2012) that find a divergence between the expectations of First Nations and government in governance and accountability frameworks.

One set of motivating concerns which has informed this exploration of the possibilities of accountability lies in the exclusion of ethical considerations from the formal processes of hierarchical accountability. At first sight what have been described as socializing forms of accountability seem to offer a model for how organizational accountability might be transformed, in a way that might temper the pursuit of strategic objectives with ethical concerns. In practice, however, it is difficult to conceive of how the informal could become the basis for an alternative organizational order, however morally desirable this might be.

We extend this literature by proposing a nonhierarchical, network form of accountability for the First Nations community, which may also be relevant in non–First Nations settings requiring governance of a common pooled resource. Our study has major implications for practice, as it suggests what First Nations healthcare operational and accountability environment could look like when the governance of healthcare is eventually transitioned to First Nations leadership. This is particularly relevant given that the transition to self-governance is underway. In June 2019, the Métis Nation signed a landmark and historic self-government agreement with the Government of Canada (Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada 2019), which covers scope and jurisdiction as well as dual citizenship (Métis Nation of Alberta 2019).

The governance framework between Canada and the provinces for Canada Health Transfers has evolved since its inception. The reality, however, is that the existing operational and accountability frameworks for First Nations date back to the Indian Health Policy of 1979 and consequently also need revamping. The time has come to revisit these policy frameworks and to envision a new First Nations healthcare governance and accountability model for Canada that reflects the network form of accountability desired by the Custodians. Furthermore, as the Métis self-government agreement and other similar agreements are translated from strategic documents into practice by actors on both sides, it is crucial that the Canadian government contemplates what accountability might look like in the relationship. While current policies, operations, and accountability frameworks are developed and activated to resolve immediate accountability problems, there needs to be a strategic approach and consideration, including planning, for future First Nations healthcare based on a viable governance and accountability model, such as the network accountability proposed in this study.