Trends in pain undertreatment among lung cancer patients at the EOL: Analysis of urban city medical insurance data in China

Jiani Zheng, Yihua Huang, Junyi He and Huaqiang Zhou contributed equally to this work and share first authorship.

[Correction added on 16 February 2024, after first online publication: the 4th author's given name has been amended from ‘Huangqiang’ to ‘Huaqiang’.]

Abstract

Background

Cancer-related pain is one of the common priority symptoms in advanced lung cancer patients at the end-of-life (EOL). Alleviating pain is undoubtedly a critical component of palliative care in lung cancer. Our study was initiated to examined trends in opioid prescription-level outcomes as potential indicators of undertreated pain in China.

Methods

This study used data on 1330 patients diagnosed with lung cancer of urban city medical insurance in China who died between 2014 and 2017. Opioid prescription-level outcomes were determined by annual trends of the proportion of patients filling an opioid prescription, the total dose of opioids filled by decedents, and morphine milligram equivalents per day (MMED) at the EOL (defined as the 60 days before death). We further analyzed monthly changes in the number of opioid prescriptions filled, MMED, and mean daily dose of opioids per prescription (MDDP) of the last 60 days of life by year at death and age, respectively.

Results

A total of 959 patients with exact dates of death were included, with 432 cases (45.06%; 95% CI: 44.36%–45.77%) receiving at least one opioid prescription at the EOL. The declining trends were shown in the proportion of patients filling any opioid prescription, the total dose of opioids filled by decedents and MMED, with an annual decrease of 0.341% (p = 0.01), 104.23 mg (p = 0.011) and 2.84 mg (p = 0.014), respectively. Within the 31–60 days to the 0–30 days of life, the MMED declined 6.08 mg (95% CI: −7.14 to −5.03; p = 0.000351), while the number of opioid prescriptions rose 0.66 (95% CI: 0.160–1.16; p = 0.025). Like the MMED, the MDDP fell 4.11 mg (95% CI: −5.86 to −2.37; p = 0.005) within the last month before death compared to the previous month.

Conclusion

Terminal lung cancer populations in urban China have experienced reduced access to opioids at the EOL. The clinicians did not prescribe a satisfactory dose of opioids per prescription, while the patients suffered increasing pain in the last 30 days of life. Sufficient opioid analgesic administration should be advocated for lung cancer patients during the EOL period.

INTRODUCTION

Cancer-related pain is one of the common priority symptoms in advanced lung cancer patients in the last days of life.1-3 Patients with unrelieved pain have a higher risk of mood disorders such as depression, stress, and anxiety,4-7 and would even experience fear of disease progression and death at the end-of-life (EOL).8 Nearly 20% of new cancer cases in the world are reported in China, making cancer pain management a topic worth noting of the country.9

The existing evidence implies a significant increase in patients' physical suffering during their last year of life, especially with a rapid increase in the last 2 months among patients with solid metastatic cancers.10 According to a report based on 1754 patients, persistent or severe pain is more prevalent even in the last weeks of life among terminal cancer patients.11 Insufficient pain management would definitely impact the quality of life for these patients in the last phase of life.

Alleviating pain is a critical component of palliative care in cancer.12 Opioids are the mainstay of moderate-to-severe cancer pain treatment.12 A survey on cancer pain identified inadequate pain assessment, insufficient staff knowledge of pain management, strict state regulation of opioid prescribing, and lack of access to strong and high-potency analgesics are becoming obstacles to optimal cancer pain management.13 However, it is unclear whether cancer pain is properly managed for lung cancer patients near the EOL in China. We therefore investigated annual and monthly changes of opioids prescription-level outcomes among lung cancer patients in the last 60 days of life. The study cohort was derived from urban city medical insurance in China between 2014 and 2017, aimed to examine trends in opioid prescription-level outcomes as potential indicators of undertreated pain among lung cancer patients.

METHODS

Data and patients

The present study selected patients diagnosed with lung cancer (ICD-10 C33-34) in Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance (UEBMI) and Urban Resident Basic Medical Insurance (URBMI) of Guangzhou, China who died between 2014 and 2017. In China, UEBMI and URBMI were two different social health insurances which were established to cover more than 95% of urban residents, containing primary care records of inpatient and outpatient medical information across different medical institutions in each patient's identity. Patients had medical records at least 1 year before death to ensure continued medical treatment in the same city.

All healthcare utilization and treatment data were provided by the Guangzhou Municipal Medical Insurance Bureau integrating hospital information system, health insurance database and population information database with the identification card number. Patient-level data on age, sex, date of death, diagnosis, prescription treatments at the EOL were included in our study.

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013) and approved by Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center IRB (B2022-153-01).

Outcomes

Only lung cancer patients with exact records of death date were included. We identified all outpatient and inpatient opioid prescriptions filled ≤60 days before death. The reviewed drugs were strong short-acting (SSA) opioids (including immediate-release morphine, oxycodone, and hydromorphone), weak short-acting (WSA) opioids (including codeine, dihydrocodeine, and tramadol), and long-acting (LA) opioids (including extended-release morphine, oxycodone and transdermal fentanyl). Methadone, meperidine and pentazocine prescriptions were excluded from the calculations due to no reliable equianalgesic conversion values were reported for these agents.14, 15 Each dose of transdermal fentanyl was considered as a 3-day supply.

(1) The proportion of patients with lung cancer filling opioid prescriptions was calculated by dividing the number of patients receiving ≥1 opioid prescription by the total number of decedents that year. (2) We multiplied the total dose of each prescription filled in the given period by standard conversion factors,15 summed across all a patient's prescriptions, and averaged to obtain a daily dose in morphine milligram equivalents per day (MMED). (3) The mean total dose of opioids by decedents was calculated by summing the morphine equivalent dose of all opioid prescriptions filled by decedents at the EOL in a given year, and dividing it by the total number of decedents that year. (4) Mean daily dose of opioids per prescription (MDDP) were calculated by dividing MMED by the number of opioid prescriptions in the given period.

Opioid prescription-level outcomes were determined by annual trends of the proportion of patients filling an opioid prescription (calculated overall and by medication type), the total dose of opioids filled by decedents and MMED in the 60 days before death. In addition, monthly changes in the number of opioid prescriptions filled, MMED and MDDP of the last 60 days of life were also analyzed by year at death and age, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to assess the prescription-level outcomes. Exact methods were used to calculate 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Simple linear regression qualified annual trends in the proportion of patients with lung cancer filling any/LA/SSA/WSA opioid prescriptions, the total dose of opioids filled by decedents and MMED at the EOL because the EOL data were normal distribution. A paired sample t-test was used to examine the changes of the preceding and following month of each prescription-level outcome in the same group. All statistical analyses in the study were analyzed by IBM SPSS Statistics (version 26). A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Study population

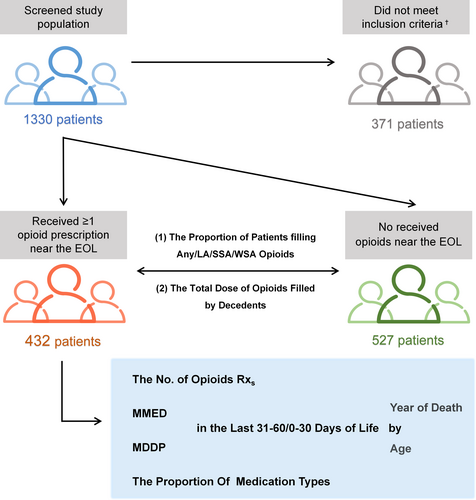

The study included 959 lung cancer patients who died between 2014 and 2017 with exact records of death date, and 432 patients who received ≥1 opioid prescription in the last 60 days of life were screened for further investigation (Figure 1). Patients' average age at death was 65.78 years (standard deviation [SD], 12.03 years). The female-to-male ratio of lung cancer patients was approximately 1:1.7 (37.73% vs. 62.27%). The hospice length of stay near the last 90 days of life were 40.97 days (SD, 23.31 years) (Table 1).

| Characteristics | Total EOL study population | Received ≥1 opioid prescription near the EOL Study population | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | % | Mean | SD | No. of patients | % | Mean | SD | |

| Overall population | 959 | 100 | 432 | 100 | ||||

| Year of death | ||||||||

| 2014 | 257 | 26.80 | 116 | 26.85 | ||||

| 2015 | 320 | 33.37 | 145 | 33.56 | ||||

| 2016 | 254 | 26.49 | 114 | 26.39 | ||||

| 2017 | 128 | 13.35 | 57 | 13.19 | ||||

| Age, years | ||||||||

| <50 | 58 | 6.05 | 68.03 | 12.07 | 31 | 7.18 | 65.78 | 12.03 |

| 50–59 | 197 | 20.54 | 109 | 25.23 | ||||

| 60–69 | 267 | 27.84 | 137 | 31.71 | ||||

| 70–79 | 249 | 25.96 | 92 | 21.30 | ||||

| 80–89 | 174 | 18.14 | 55 | 12.73 | ||||

| ≥90 | 14 | 1.46 | 8 | 1.85 | ||||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 600 | 62.57 | 269 | 62.27 | ||||

| Female | 359 | 37.43 | 163 | 37.73 | ||||

| Presence of chronic illness | ||||||||

| Essential hypertension | 569 | 59.33 | 258 | 59.72 | ||||

| Diabetes | 194 | 20.23 | 95 | 21.99 | ||||

| Ischemic heart disease | 192 | 20.02 | 98 | 22.69 | ||||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 147 | 15.33 | 75 | 17.36 | ||||

| Cerebral stroke | 157 | 16.37 | 66 | 15.28 | ||||

| Chronic renal failure | 37 | 3.86 | 21 | 4.86 | ||||

| Hip or pelvic fracture | 23 | 2.40 | 16 | 3.70 | ||||

| Alzheimer or other dementias | 35 | 3.65 | 12 | 2.78 | ||||

| Hospice length of stay near the EOL | 42.34 | 23.23 | 40.97 | 23.31 | ||||

- Abbreviations: EOL, end-of-life; SD, standard deviation.

Annual trends in opioid prescription-level outcomes at the EOL

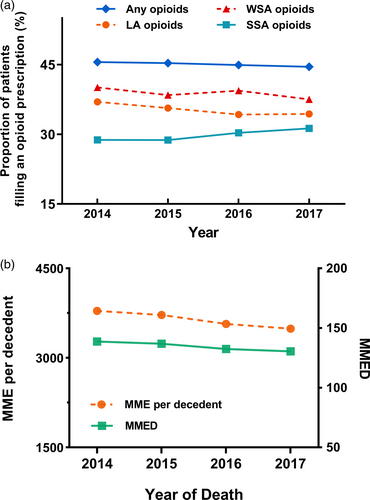

Under half the patients (45.06%; 95% CI: 44.36%–45.77%) filled ≥1 opioid prescription at the EOL from 2014 to 2017, and the proportion of patients filling any opioid prescription showed a slight but significant declining trend with an annual decrease of 0.341% (p = 0.01). The prescription rate of LA, WSA and SSA did not change statistically in a given period (p = 0.07; p = 0.217 and p = 0.056) (Figure 2a, Data S1).

The total dose of opioids filled by lung cancer decedents at the EOL (averaged across those who did and did not receive an opioid) fell 104.23 mg annually (95% CI: −152.26 to −56.20, p = 0.011), from 3796.43 morphine milligram equivalents to 3489.31 morphine milligram equivalents per decedent. Among patients prescribed ≥1 opioid prescription in the last 60 days, the population mean daily dose fell 2.84 mg (95% CI, −4.31 to −1.36, p = 0.014) annually, from 138.62 MMED to 130.59 MMED between 2014 and 2017 (Figure 2b, Data S1).

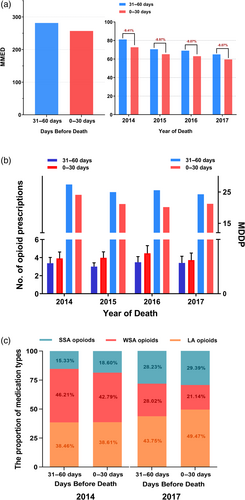

Monthly changes in opioids prescription-level outcomes at the last 60 days of life

Among patients prescribed ≥1 opioid prescription at the EOL, the MMED declined 6.08 mg (95% CI: −7.14 to −5.03; p = 0.000351) from the last 31–60 days to the 0–30 days before death (Data S1). The gap of decline rates in MMED over 2 months decreased from 9.41% to 8.07% during the years 2014–2017 (Figure 3a).

The number of opioid prescriptions near the EOL rose 0.66 (95% CI: 0.160–1.16; p = 0.025) month over month at the EOL (Data S1). In addition, the MDDP displayed a similar decline as the MMED – falling 4.11 mg (95% CI: −5.86 to −2.37; p = 0.005) within the last month before death compared to the previous month (Figure 3b, Data S1).

As for the medication types provided to patients filling ≥1 opioids at the EOL, the proportion of SSA and LA opioids significant rose in 2017 compared with 2014, while the proportion of WSA opioids reduced. In 2017, there was an increase of 5.72% in the proportion of LA opioids in the last 0–30 days compared with the last 31–60 days before death (from 43.75% to 49.47%). The proportion of WSA opioids fell from 28.02% to 21.14% in parallel (Figure 3c).

The MMED declined sharply with increasing age at death (−45.75 mg, 95% CI: −52.65 to −38.85, p = 0.000051) at the EOL (Figure 4a, Table S6). As patients approached death, the number of opioid prescriptions increased over the 31–60 to the 0–30 days of life among all age groups (0.69; 95% CI: 0.36 to 1.01, p = 0.003; Data S1). Simultaneously, the MDDP declined 2.33 mg (95% CI: −3.55 to −1.11; p = 0.004) in all age groups (Figure 4b, Data S1).

DISCUSSION

The inadequate control of cancer pain remains a worldwide problem.16, 17 A survey conducted in seriously ill patients and their families revealed that 55% of the patients were conscious in the last 3 days of life, and 40% of the patients had severe pain most of the time.18 In patients with advanced lung malignancies, a study supported that up to 47% of the patients suffered significant pain even in the last 48 h of life.19 Insufficient pain management of cancer patients in the last days of life is a common medical problem, but one that is rarely discussed openly. Through reviewing the urban city medical insurance data of lung cancer patients in China, our study first showed that the problem of analgesic undertreatment exists among patients with lung cancer at the EOL.

In our study, opioid prescribing at the EOL fell annually in numerous ways, including the proportion of patients filling any opioid prescription, the total dose of opioids filled by decedents and MMED. Long-acting opioids had a relatively small but no significant decreasing trend in opioid prescribing at EOL. Indeed, the use of fentanyl transdermal patches may be limited by the shortage selection of drug regular specifications in China. Only 4.2 mg and 8.4 mg of specifications can be accessed in medical institutions, making it difficult to titrate fentanyl dosage against pain relief. Such limited dose options of the drug might therefore indirectly restrict the use of LA opioid analgesics. Yet, LA medications are recognized as a last resort for severe cancer pain, which cannot be well managed by weak opioids.12 Moreover, the prescription rate of WSA in our study was much higher than that reported in patients with various types of cancer from other countries,20 which might be due to the wide use of cough suppressants such as codeine and dihydrocodeine in lung cancer compared with other cancers. The prevalence of opioid prescriptions is an appropriate proxy for determining the quality of palliative cancer care. It is therefore problematic to observe the continuously annual decline of EOL opioid utilization among terminal lung cancer populations.

Worsening opioid access in the last 30 days of life was explored as a potential cause of undertreated EOL pain in lung cancer patients. We further examined the changes of opioid prescription-level outcomes between the 31–60 days and the 0–30 days of life among patients who received ≥1 EOL opioid prescription. Declines in MDDP were accompanied by a rising number of opioid prescriptions month over month in the last 60 days of life, suggesting that the clinicians did not prescribe a satisfactory dose of opioids per prescription even though the patients suffered increasing pain. Fortunately, the awareness of appropriate opioid analgesic administration has improved among the clinicians – reflected by the narrowing gap of decline rate in MMED over 2 months year by year as well as the rising proportion in filling of LA opioids in 2017 compared with 2014. These trends may point to the positive effects of the Good Pain Management (GPM) Ward Program launched in China.21

Pain screening by clinicians is the first step to manage cancer patient pain. A survey to 500 oncologists reflected that the main barriers to better pain administration were patient reluctance to use opioids and inadequate staff knowledge of pain management.22 According to an observational study using functional positron emission tomography scans of the brain, pain can be perceived even in patients with a minimally conscious state.23 However, the ability to swallow and speak reduced in patients at the EOL, which may mislead clinicians that analgesic treatment is unnecessary for these patients Additionally, the inherent concerns of opioid-induced adverse events (AEs) also restrict the clinical medication of opioids in a real-world clinical context.24-27 Opioid-induced respiratory depression (OIRD) is generally caused by opioid overdose and in the postoperative period with an incidence rate of 0.001%–1%,28-30 but does not commonly happen in terminal cancer patients. It is thought that potentially life-threatening OIRD decreases in breathing frequency,31 yet pain stimulates respiration and increases respiratory rate that can attenuate morphine-induced respiratory depression.27, 32, 33 As for the common nonlife-threatening AEs such as constipation, nausea, and vomiting that arise from opioids, multiple symptomatic strategies are available to achieve better clinical management.34 Additionally, somnolence can be induced by opioids as another nonlife-threatening AE, while the drug does not affect patient consciousness when it used for the alleviation of pain.35 Therefore, opioid-induced AEs should not be the reason for reducing the dosage of opioid prescriptions, especially since existing empirical evidences have illustrated increased suffering at the EOL in terminal cancer patients.

When assessing EOL prescription-level outcomes by age in the present study, we observed that MMED fell significantly with increasing age. While previous studies have reported that the prevalence of significant pain decreases with age,36, 37 the reliability of reports of modest to severe pain by elderly patients may be compromised by cognitive factors, differences in pain tolerance, or differential response to pain medications.37 Moreover, the prevalence of pain was high in patients with chronic disease.38-42 It is worth noting that two or more comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, cardiac disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and renal disease were identified as significant risk factors for OIRD.43, 44 The half-lives of opioids and their metabolites apparently increased due to age or disease-related reduction in renal and hepatic function in elderly patients and patients with chronic disease.45, 46 Therefore, careful and intensive monitoring is of great importance for these patients who are administered opioids. Balance should be aimed for between the benefit and potential disadvantages of opioid analgesics for elderly patients and patients with chronic disease.

Physicians from seven countries generally agree that terminally ill patients should receive pain alleviation if necessary, despite a possible life-shortening effect.47 The GPM Program in China encourages physicians to pay more attention to cancer pain, improve their medical knowledge of appropriate analgesic administration and embolden them to use strong opioids more actively.21 The 2014 World Health Assembly resolution and The Lancet Commission on Palliative Care and Pain Relief have also emphasized the urgency of reducing suffering near the EOL.31, 48 Opioids are the cornerstone of treating moderate-to-severe cancer pain. To date, opioids are even allowed for the treatment of dyspnea that is induced by the inevitable progression of thoracic tumors in patients with advanced lung cancer.49-53 The high prevalence of palliative pain and dyspnea in patients with lung cancer support that most patients could benefit from opioids.54 Therefore, aggressive symptom relief may be needed and the attendance and empathy for patients are paramount if existing pain treatment is inadequate for palliative care patients.

The present study had several limitations. First, we screened the patients with detailed death dates, so only patients who died during hospitalization were included for analysis. Data on patients who died at home were not available. In fact, pain management is more limited for these patients without inpatient palliative care services. Second, due to the limitation of available data, prevalence and intensity of pain cannot be directly evaluated by analgesic prescription despite previous studies confirming an increase in suffering among terminally ill patients as death approaches. Third, whether patients used the prescribed opioids could not be determined, while prescription records were reasonable to deduce the current situation. Lastly, our study was conducted in multiacademic medical centers with an entirely Asian patient population. Physicians' attitudes and practices towards end-of-life decisions may vary in their countries. Therefore, more international comparative studies are needed.

In conclusion, terminal lung cancer populations in urban China have experienced reduced access to opioids at the EOL. We found a rising number of EOL opioid prescriptions among patients with lung cancer, suggesting an increase in suffering in lung cancer patients as death approaches. However, the decrease in MDDP indicated that the clinicians did not prescribe a satisfactory dose of opioids per prescription for the patients in the last 30 days before death. Therefore, sufficient EOL opioid analgesic administration should be advocated for lung cancer patients in developing the suitable policy solutions and good attendance and full knowledge of clinicians.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors had full access to the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Conceptualization: Jiani Zheng and Yihua Huang. Investigation: Jiani Zheng, Yihua Huang, Junyi He and Huaqiang Zhou. Resources: Jiani Zheng, Yihua Huang, Huaqiang Zhou, Tingting Liu and Mengting Shi. Data curation: All authors. Formal analysis: Jiani Zheng, Yihua Huang, Huaqiang Zhou, Tingting Liu, Junyi He and Jie Huang. Writing-original draft: Jiani Zheng, Yihua Huang and Huaqiang Zhou. Writing-review and editing: all authors. Project administration: Yuanyuan Zhao, Wenfeng Fang, Yunpeng Yang and Li Zhang. Funding acquisition: Huaqiang Zhou and Wenfeng Fang, Y.unpeng., and Li Zhang. Supervision: Li Zhang. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 82241232, 82072558, 82173101, 82272789, 82102864).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this study.