Long-term results of a randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled phase III trial: Endostar (rh-endostatin) versus placebo in combination with vinorelbine and cisplatin in advanced non-small cell lung cancer

Abstract

Background:

Phase II-III trials in patients with untreated and previously treated locally advanced or non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) suggested that Endostar was able to enhance the effect of platinum-based chemotherapy (NP regimen) with tolerable adverse effects.

Methods

Four hundred and eighty six patients were randomized into two arms: study arm A: NP plus Endostar (n = 322; vinorelbine, cisplatin, Endostar), and study arm B: NP plus placebo (n = 164; vinorelbine, cisplatin, 0.9% sodium chloride). Patients were treated every third week for two to six cycles.

Results:

Overall response rates were 35.4% in arm A and 19.5% in arm B (P = 0.0003). The median time to progression was 6.3 months for arm A and 3.6 months for B, respectively (P < 0.001). The clinical benefit rates were 73.3% in arm A and 64.0% in arm B (P = 0.035). Grade 3/4 neutropenia, anemia, and nausea/vomiting were 28.5%, 3.4%, and 8.0%, respectively, in Arm A compared with 28.2%, 3.0%, and 6.6%, respectively, in Arm B (P > 0.05). There were two treatment related deaths in arm A and one in arm B (P > 0.05). The median overall survival was longer in arm A than in arm B (P < 0.0001).

Conclusion:

Long-term follow-up revealed that the addition of Endostar to an NP regimen can result in a significant clinical and survival benefit in advanced NSCLC patients, compared with NP alone.

Introduction

Lung cancer is the most common cause of cancer-related death in China,1, 2 and has been the leading cause of male cancer death.1-3 For the last 10 years, treatment has consisted of cisplatin-doublet chemotherapy and supportive care. The response rate and one-year survival is 20–25% for first-line treatment and 8–15% for the second-line.4, 5

Invasive tumor growth or metastasis, involves the sprouting of new blood vessels from existing capillaries. Folkman (1971), in his research work on angiogenesis, first highlighted that cancer progression is critical for malignancy growth.6 The extent of tumor growth, beyond a size of 2 mm3, requires the vascular network to transport nutriment. Anti-angiogenic molecules are, therefore, considered to offer novel therapeutic modalities for the treatment of tumors. Investigations of different anti-angiogenesis and vascular targeting strategies for numerous tumor types, including lung carcinoma, are currently in progress. More than a dozen endogenous proteins that act as positive regulators of tumor angiogenesis have been identified.7 Endogenous mammalian proteins that inhibit endothelial cell growth may play a physiologic role in maintaining the normally low replication rate of vascular endothelial cells, and include angiostatin and endostatin.8-10

Endostatin, a 20 kDa C-terminal globular domain of the collagen XVIII, was originally isolated from the supernatant of a cultured murine hemangioendothelioma cell line for its ability to inhibit tumor angiogenesis.11 In animal models, tumor dormancy could be induced by repeated administration of endostatin for several cycles without causing drug resistance. Endostatin exhibits potent anti-endothelial cell activities, including inhibition of cell proliferation, migration, adhesion, and survival, which are all required for angiogenesis in vivo. Endostatin has been reported to have low toxicity in both animal studies and human trials.12-15

Rh-endostatin (code number YH-16, commercial name Endostar) is a new recombinant human endostatin developed by Luo YZ's group in Simcere-Medgenn Bioengineering Co. Ltd, Nanjing and Yantai, China, and is different from the original endostatin studied by O'Reilly.12, 13 Endostar is designed to stop cancer by nullifying a tumors ability to obtain oxygen and nutrients for growth. Endostar works by inhibiting angiogenesis: the proliferous formation of new blood vessels in and around the tumoral tissue. Preclinical studies have shown that this novel agent could inhibit tumor growth and shrink existing tumor blood vessels.16-18

A phase-I clinical trial conducted in China showed that Endostar was well tolerated. The efficacy of Endostar was evident in inhibiting tumor growth (one patient with malignant melanoma had a minor response and five patients showed stable disease).19 A phase-II B trial of Endostar in combination with NP demonstrated an increase in response rate and decrease in adverse events, compared with bi-therapy of NP in patients with advanced non small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC).20 A phase-III trial of Endostar in combination with NP versus placebo plus NP for advanced NSCLC was conducted from April 2003 to June 2004. The preliminary results were reported in 2005.21, 22 Endostar was approved by the Chinese Food and Drug Administration as an official new anticancer drug in 2006, and has been widely used in advanced NSCLC. This report presents the data of long-term follow up of patients in the phase III study, along with an analysis of the factors influencing survival of NSCLC patients.

Methods

Patients

Patients eligible for the study were those with locally advanced and metastatic NSCLC, confirmed by histology or cytology, with bi-dimensionally measurable disease. Inclusion criteria included: an age of 18 to 75 years, an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) of 0 to 2, a life expectancy of more than three months, no allergic history to biologic therapy, and written informed consent. In addition, the following results were required in order to be eligible for our study: adequate organ function, as indicated by a white blood cell count ≥4000/μL, absolute granulocyte count (AGC) ≥1500/μL, hemoglobin level ≥9.5 g/dL, platelet count ≥10 000/μL, total bilirubin level ≤1.5 times the upper limit of normal (ULN), serum transaminase level ≤2 times ULN, and prothrombin time (PT)/protein truncation test (PTT) ≤1.5 times ULN. Patients who were on an NP regimen and had ceased treatment for more than six months were permitted in the study. Patients who were treated with nitrosoureas or mitomycin C for more than six weeks or with the other chemotherapeutic drugs for more than four weeks prior to the study were permitted. Subjects (or their legally acceptable representatives) were required to sign an informed consent document indicating that they understood the purpose of and procedures required for the study and were willing to participate.

Exclusion criteria included ongoing anticancer therapy, chemotherapy with NP within six months before the initiation of study, receipt of other therapy (radiotherapy, chemotherapy, biological therapy) or clinical trial within one month of the study, clinically significant cardiovascular disease, presence of pregnancy or lactation, presence of hepatic and renal dysfunction, unmanageable psychosis, and uncontrolled central nervous system metastasis.

Study design and treatment

This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, and multi-center trial. Eligible patients were randomly assigned to receive Endostar plus NP or placebo plus NP in a 2:1 ratio. Patients received either Endostar plus NP (vinorelbine 25 mg/m2 on days one and five, cisplatin 30 mg/m2 on days two through four, and Endostar 7.5 mg/m2 on days one through 14), or placebo plus NP (vinorelbine 25 mg/m2 on days one and five, cisplatin 30 mg/m2 on days two through four, 0.9% sodium-chloride 3.75 mL on days one through 14) for two to four three-week cycles. Treatment with the two regimens was discontinued if disease progression, symptomatic deterioration, or unacceptable toxicity occurred during the study, or where there was a delay to treatment of more than two weeks or grade 4 hematological toxicity, or until consent was withdrawn. All patients were followed up for three years. The Ethics and Scientific Committees of the participating hospitals in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and current State Drug Administration Good Clinical Practices approved the protocol.

Assessment of efficacy and safety

The primary end point was the overall rate of response (RR) to the treatment (including complete response and partial response). Secondary end points included the time to progression (TTP), overall survival (OS), clinical benefit rate (CBR), quality-of-life (QoL) assessment, improved disease-related symptoms, and safety during treatment. An evaluation of response was performed after cycle 2 and was confirmed four weeks after the end of the trial. Responses were assessed based on World Health Organization (WHO) criteria by the independent experts evaluation committee (IEEC). TTP was defined as the time from the achievement of a response to progression. Quality of life was assessed with the use of the International Scales for QoL in patients with lung cancer, at each visit. Adverse events were assessed each day and graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (version 3.0) from the beginning of treatment.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software (version 8.0, SAS institute). Treatment differences for all end points were tested at a two-sided α level of 0.05. RR and CBR were compared between the two groups with the Chi-square test. The Wilcoxon test was used to compare the efficacy of the two groups. A log rank test was used to compare the TTP of the two groups. A multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to identify prognostic factors in response rate. The stratified Cox proportional- hazards model was used to assess the factors that may influence TTP or OS. In analyses of TTP, data for patients who started alternative chemotherapy, who were lost to follow-up, or who died before documentation of progressive disease were censored at the last assessment. In analyses of survival, data for patients were censored on the date they were last known to be alive, regardless of disease progression or alternative therapy.

Results

Patients and treatment

A total of 493 patients with advanced NSCLC were screened and 486 patients were randomly assigned to receive Endostar plus NP (n = 322) or placebo plus NP (n = 164) at 24 sites in China between April 2003 and June 2004. Seven patients were randomly excluded from 493 screened patients: four fell short of inclusion criteria; two had protocol deviation; and one patient was eliminated because of loss of data. The mean age was 56 years and the majority (n = 229; 71%) were males. Baseline demographic and disease characteristics of the two groups were balanced (Table 1). The median duration of treatment with Endostar plus NP and placebo plus NP was 48 days (range, 1–385) and 43 days (range, 1–257), respectively.

| Item | Endostar plus NP (n = 322) | Placebo plus NP (n = 164) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years old) | ||

| Median (range) | 57 (18–76) | 55 (32–76) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 229 (71.1%) | 117 (71.3%) |

| Female | 93 (28.9%) | 47 (28.7%) |

| ECOG score | ||

| 0 | 65 (20.2%) | 31 (18.9%) |

| 1 | 205 (63.7%) | 95 (57.9%) |

| 2 | 52 (16.1%) | 38 (23.2%) |

| Histology | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 129 (40.1%) | 55 (33.5%) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 165 (51.2%) | 98 (59.8%) |

| Others | 28 (8.7%) | 11 (6.7%) |

| TNM stage | ||

| IIIA | 51 (15.8%) | 30 (18.3%) |

| IIIB | 86 (36.7%) | 45 (27.4%) |

| IV | 185 (57.5%) | 89 (54.3%) |

| No. of metastatic organs | ||

| 0 | 35 (10.9%) | 20 (12.2%) |

| 1 | 150 (46.6%) | 81 (49.4%) |

| 2 | 92 (28.6%) | 41 (25.0%) |

| ≥3 | 45 (14.0%) | 22 (13.4%) |

| Treatment history | ||

| Surgery | 36 (11.2%) | 23 (14.0%) |

| Radiotherapy | 35 (10.9%) | 24 (14.6%) |

| Chemotherapy | 92 (28.6%) | 47 (28.7%) |

| Chemotherapy-naive | 230 (71.4%) | 117 (71.3%) |

- ECOG, Eastern cooperative oncology group; TNM, tumor node metastasis.

Efficacy

A total of 486 patients were determined to be suitable for evaluation if they had received at least one dose of a study drug and had measurable disease at baseline. The response rate (including complete response, partial response) was 35.4% in the Endostar plus NP group and 19.5% in the placebo plus NP group (P = 0.0003). The median TTP was 6.3 months (189 days) in the Endostar plus NP group and 3.6 months (108 days) in the placebo plus NP group. The clinical benefit rate was 73.3% in the Endostar plus NP group and 64% in the placebo plus NP group (P = 0.035). In improvement of disease-related symptoms, such as cough, expectoration, hemoptysis, and chest pain, the Endostar plus NP group showed better responses than the placebo plus NP group.

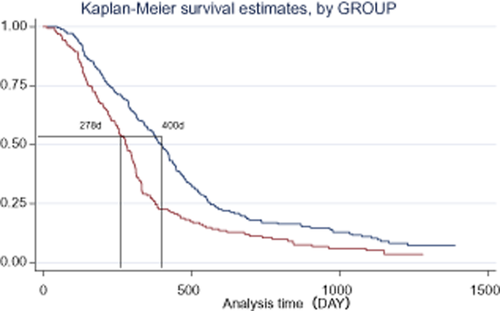

Long-term Survival

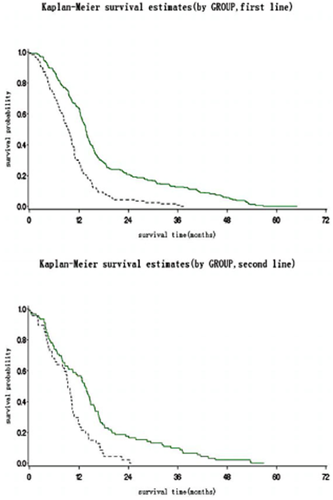

After more than five years of follow up, patients who received Endostar plus NP had a longer median overall survival (13.75 months, 418 days 95% confidence interval [CI] 394–437 days) than those who received the placebo plus NP (9.77 months, 297 days 95% CI 257–313 days, P < 0.0001). There was a statistically significant difference between the two treatment groups in the patients untreated previously (400 days vs. 278 days P = 0.0001 (Figs 1, 2). In addition, the QoL score in the Endostar plus NP group and placebo plus NP group was increased from baselines of 49.37 ± 6.27 and 49.19 ± 6.22 to 54.41 ± 3.68 and 53.67 ± 5.88, respectively (Table 2). There was a significant difference between the two groups by the end point (P = 0.0155).

Survival of patients in Endostar and placebo groups.  , Endostar plus NP;

, Endostar plus NP;  , Placebo plus NP.

, Placebo plus NP.

Survival of patients in Endostar and placebo group in first-line and relapsed patients. Group:  , Endostar;

, Endostar;  , Endostar (censor);

, Endostar (censor);  , placebo;

, placebo;  , placebo (censor).

, placebo (censor).

| QoL | ITT | PP | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endostar + NP | Placebo + NP | Endostar + NP | Placebo + NP | |

| Baseline | ||||

| N (Missing) | 322 (0) | 164 (0) | 289 (0) | 160 (0) |

| Mean (SD) | 49.37 (6.27) | 49.19 (6.22) | 49.57 (6.12) | 49.21 (6.25) |

| Median | 50.00 | 50.00 | 50.00 | 50.00 |

| Min, Max | 24.00, 60.00 | 28.00, 60.00 | 24.00, 60.00 | 28.00, 60.00 |

| 4 Cycles | ||||

| N (Missing) | 27 (295) | 12 (152) | 27 (262) | 12 (148) |

| Mean (SD) | 54.41 (3.68) | 53.67 (5.88) | 54.41 (3.68) | 53.67 (5.88) |

| Median | 55.00 | 56.00 | 55.00 | 56.00 |

| Min, Max | 44.00, 60.00 | 44.00, 60.00 | 44.00, 60.00 | 44.00, 60.00 |

| N (Missing) | 27 (295) | 12 (152) | 27 (262) | 12 (148) |

| 4 Cycles – Baseline | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 3.56 (5.88) | 4.67 (4.96) | 3.56 (5.88) | 4.67 (4.96) |

| Median | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 |

| Min, Max | 10.00, 19.00 | 1.00, 18.00 | 10.00, 19.00 | 1.00, 18.00 |

| Paired t | 3.1425 | 3.2589 | 3.1425 | 3.2589 |

| P | 0.0042 | 0.0076 | 0.0042 | 0.0076 |

| Analysis of Covariance | ||||

| Factor | F | P | ||

| Group | 6.00 | 0.0155 | ||

| Baseline | 101.50 | <0.0001 | ||

| Initial or Re-treatment | 0.20 | 0.6538 | ||

- ITT, intent to treat; QOL, quality of life; PP, per-protocol; SD, stable disease.

Sub-group analysis

In patients with first treatment, the RR (40.00% vs. 23.93%, P < 0.01), TTP (6.61 months vs. 3.65 months, P < 0.001) and CBR (76.52% vs. 64.96%, P < 0.05) of the Endostar plus NP group were higher than those of placebo plus NP group. In patients with pre-treated NSCLC, the RR (23.91% vs. 8.51%, P < 0.05) and TTP (5.72 months vs. 3.16 months, P < 0.001) were higher in the Endostar plus NP group than in the placebo plus NP group, but there was no significant difference in CBR between the two groups (65.22% vs. 61.70%, P > 0.05). Male patients with ECOG PS scores of 0–1, squamous cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma, over 40 years of age, or stage IV, had higher RR in the Endostar plus NP group than in placebo plus NP group (P < 0.05). Female patients with ECOG PS score 0, over 60 years of age, stage IIIb, or previously untreated, had a higher CBR in the Endostar plus NP group than in the placebo plus NP group (P < 0.05).

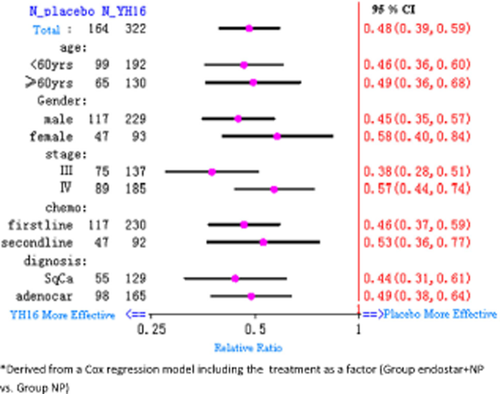

Prognostic factors

Prognostic factors, such as type or number of previous therapies, type of NSCLC, clinical stage, gender, age, PS score, bodyweight index, and metastasis were analyzed with logistic regression. The results showed that RR and TTP were favourable in the Endostar plus NP group compared to the placebo plus NP group (P < 0.05) (Tables 3, 4, Fig 3).

Prognostic factors influencing the survival of patients in the two groups.

| Factor | P-value | RR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment group | 0.0006 | 0.44 | 0.28–0.71 |

| Age | 0.18 | 0.99 | 0.97–1.00 |

| Gender | 0.018 | 1.73 | 1.01–2.71 |

| Body index | 0.025 | 0.92 | 0.86–0.99 |

| ECOG PS score | 0.012 | 0.64 | 0.45–0.91 |

| Complicated disease | 0.25 | 0.70 | 0.39–1.28 |

| Duration of Disease | 0.59 | 0.99 | 0.97–1.02 |

| TNM stage | 0.66 | 1.002 (III B vs. III A) | 0.512–1.962 |

| 1.236 (IV vs. III A) | 0.648–2.358 | ||

| Metastasis status | 0.68 | 0.86 | 0.41–1.78 |

| Naïve or relapsed | 0.0032 | 0.43 | 0.24–0.75 |

- CI, confidence interval; ECOG, Eastern cooperative oncology group; PS, performance status; RR, response rate; TNM, tumor node metastasis.

| Factor | Time to progression | OS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-value | RR | 95% CI | Comparison | P-value | RR | 95% CI | Comparison | |

| Treatment group | <0.0001 | 2.60 | 2.03–3.34 | Placebo vs. Endostar | <0.0001 | 2.012 | 1.623–2.495 | Placebo vs. Endostar |

| Age | 0.1509 | 0.99 | 0.98–1.00 | 0.8182 | 0.999 | 0.989–1.009 | ||

| ECOG score | 0.0627 | 1.22 | 0.99–1.50 | 0.0084 | 1.274 | 1.064–1.526 | ||

| Body index | 0.4739 | 1.02 | 0.97–1.06 | 0.4711 | 1.013 | 0.978–1.050 | ||

| Duration of Disease | 0.7108 | 1.00 | 0.99–1.01 | 0.9122 | 1.001 | 0.991–1.010 | ||

| Gender | 0.2082 | 0.84 | 0.64–1.10 | 2 vs. 1 | 0.3960 | 0.902 | 0.712–1.144 | 2 vs. 1 |

| Naïve or relapsed | 0.0608 | 1.33 | 0.99–1.78 | 2 vs. 1 | 0.9660 | 1.006 | 0.779–1.298 | 2 vs. 1 |

| TNM stage | 0.1371 | 1.14 | 0.96–1.36 | III B vs. IIIA | 0.7185 | 0.942 | 0.681–1.303 | IIIB vs. IIIA |

| 0.3471 | 1.22 | 0.81–1.85 | IV vs. IIIA | 0.2577 | 1.184 | 0.884–1.586 | IV vs. IIIA | |

| Complicated disease | 0.9154 | 0.98 | 0.70–1.38 | 1 vs. 0 | 0.6684 | 1.130 | 0.843–1.514 | 1 vs. 0 |

- CI, confidence interval; ECOG, Eastern cooperative oncology group; RR, response rate; TNM, tumor node metastasis.

Safety

All patients in the Endostar plus NP group had adverse events. The hematological toxicity included neutropenia (171, 53.10%), anemia (105, 32.60%), and thrombocytopenia (51, 15.83%). Non-hematologic toxicity included nausea and vomiting (165, 51.24%), fatigue (104, 32.29%), constipation (55, 17.08%), increased alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (22, 6.83%), and arrhythmia (21, 6.51%). The most common grade 3 or 4 adverse events were neutropenia (93, 28.88%), anemia (11, 3.41%), nausea and vomiting (26, 8.07%), and fatigue (12, 3.72%). The were was no significant difference in the incidence of adverse events between the two groups, and the adverse events were typically mild to moderate and were manageable with routine support. There were five deaths in the study: three in the placebo plus NP group (from serious infection), and two in the Endostar plus NP group (one from acute abdominal pain, the other from disease progression). These events were not considered to be related to the study drug.

Discussion

At present, results from chemotherapy for advanced NSCLC have reached a period of plateau.4, 5, 23 The NP regimen is one of the first-line regimens used in China. Improving the outcome of advanced NSCLC remains a priority. The growth of solid tumors is dependent upon their ability to elicit the development of new blood vessels into the tumor mass (angiogenesis). There has been an increase in attempts to target tumor vasculature in order to inhibit tumor growth. Many studies have shown that an angiogenesis inhibitor in combination with chemotherapy can improve responses and clinical benefit. In a study, bevacizumab (Avastin), a monoclonal antibody against vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), was administered along with irinotecan, bolus fluorouracil, and leucovorin for the treatment of 813 patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer.24 The results showed that the addition of bevacizumab to fluorouracil based combination chemotherapy resulted in statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in survival among patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Bevacizumab also showed promising results with chemotherapy in NSCLC and breast cancer patients.25, 26 Endostar (recombinant human endostatin) is the most potent anti-angiogenesis agent known today, because of its effective interaction with a wide range of angiogenesis promoters. Preclinical studies showed that rh-endostatin inhibited steady Lewis lung carcinoma in mice. This observation was the basis of combining rh-endostatin with chemotherapy in the management of common malignancies. In this phase III trial, our results showed significant clinical and survival benefit in the Endostar-treated group compared with the placebo group. The majority of advanced NSCLC patients tolerated the Endostar combination well.

The response rate of the control group (placebo plus NP treatment) in this trial is similar to the result of Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) phase III trial (RR, 19.5% vs. 26.0% and median TTP, 3.6 months vs. 4.0 months).27, 28 The Endostar plus NP treated group showed significantly superior RR (35.5%), median TTP (6.3 months) and OS (418 days) in patients with NSCLC compared to the placebo plus NP group (297 days). In addition, Endostar plus NP as the first treatment showed better results in RR (40.0% vs. 23.9%), CBR (76.52% vs. 65.00%), and median TTP (6.61 vs. 3.7 months). In the TAX 326 trial, 26 patients treated with docetaxel plus platinum (DC) had a median survival of 11.3 versus 10.1 months for NP treated patients, and RR was 31.6% for DC treated patients versus 24.5% for NP treated patients. We achieved similar results to the TAX 326 trial for RR of NP treated as first line chemotherapy (29.0% vs. 24.5%).29 However, in the Endostar plus NP treated group, the RR increased by 16% and median TTP (2.9 months) was longer than the RR of docetaxel plus DC treatment. These results show that two completely different mechanisms of drug synergies resulted in improved efficacy. The results from the present study further suggested that Endostar plus NP was an effective treatment option for first line treatment of advanced NSCLC.

Docetaxel is included in second line chemotherapy for standard treatment of NSCLC and has a 10% RR and six month median OS,4 while other regimens such as alimita, gefitinib, and erlotinib have a RR of under 10%.30-32 In our study, the RR of Endostar plus NP was 23.91%, showing benefits for the re-treated patients and prolonged OS for advanced NSCLC.33, 34 In this trial, the Endostar plus NP group showed a significant increase in QoL compared to the placebo plus NP group (P = 0.0155). Patients over 40 years of age (including those over 60) in the Endostar plus NP group showed higher RR and longer TTP than those in the placebo plus NP group. Patients over 60 years of age in the Endostar plus NP group had higher CBR than those in the placebo plus NP group. This suggested that elderly patients with advanced NSCLC could also benefit from the treatment of Endostar plus NP. In our study, the combination of NP and Rh-endostatin led to incidences of tachycardia that were higher than in the NP plus placebo group Further research is required to explore the pathological mechanism of the drug, which causes arrhythmia. Additional research is also required to provide a rational basis for the mechanism of multimodality therapy and to identify potential problems that might arise from endostatin plus radiotherapy, to ensure that endostatin will be successfully incorporated into computed tomography in a timely and rational manner.

After our phase III trial, there have been a number of trials in China confirming the results that Endostar can enhance the efficacy of other platinum containing regimens, such as TC, TP, PC in NSCLC,35-40 and also in gastro-intestinal cancers, such as in combination with FOLFOX 4, XELOX and XELERI regimens.41-44 Local infusion of Endostar in combination with chemotherapy may control malignant pleural and abdominal effusions.45-48 Other clinical and laboratory studies in breast and esophageal cancer, and hepatoma are also underway.49-52

Endostar acts on the surface of cells through nucleolin and may enhance the activity of chemotherapy.53, 54 Studies are ongoing to find the correlation between nucleolin and the clinical effect of Endostar in order to determine predictive factors in NSCLC patients. The successful clinical response to gefitinib and erlotinib in lung cancer, through the mutation of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), has created such a possibility.55, 56

Conclusion

The addition of Endostar in NP chemotherapy could result in statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in efficacy and survival in NSCLC patients, both in first- and second-line treatment. Endostar in combination with chemotherapy induces a clinically significant response, with manageable adverse effects. As part of combination therapy, Endostar has proven a safe and effective drug and could be added to current treatment strategies in the NCCN China Edition clinical guideline for advanced NSCLC patients.

Acknowledgment

This study was funded by Simcere-Medgenn Bioengineering Co.

Disclosure

No authors report any conflict of interest.