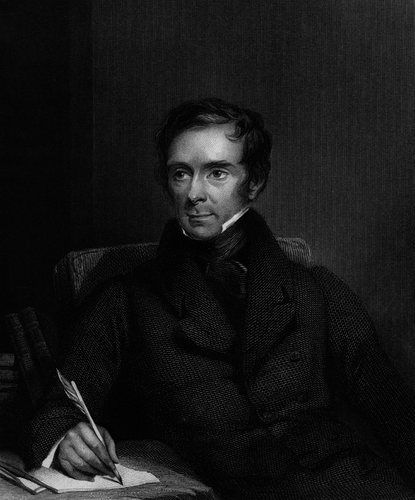

Sir Benjamin Collins Brodie (1783–1862) – a pioneer rheumatologist

Abstract

Aim

Sir Benjamin Collins Brodie (1783–1862) was a London surgeon who investigated joint disease by observation and morbid anatomy in the first half of the 19th century. His descriptions of inflammatory joint disease have been referred to in the past, but only in a fragmentary way. This study aimed to provide more detail than previously, allowing for a new appreciation of his contributions.

Methods

The authors used the first (1818), third (1834) and fifth (1850) editions of his book, Pathological and Surgical Observations on the Diseases of Joints, to provide his description of reactive arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis.

Results

Brodie's descriptions are admirably clear. He describes reactive arthritis in the first edition of his book more completely than authors before him and even Reiter a century later. He recognised that the conjunctivo-urethral-synovial syndrome can occur independently of gonorrhoea, that there are often repeated attacks, and that irits is a complication – the first indication that this syndrome might be part of what we now call seronegative spondyloarthritis. The fifth edition (1850) has among the earliest descriptions in English of ankylosing spondylitis and rheumatoid arthritis.

Conclusion

Brodie's understanding of rheumatic diseases, and his willingness to pass this knowledge on, demands that he be widely recognised as a pioneer rheumatologist.

Sir Benjamin Collins Brodie (Fig. 1), 1st Baronet, was a surgeon at St. George's Hospital, London. Several surgical conditions are linked to his name (Brodie's abscess, Brodie's pile and Brodie's tumor), but his best work came from the sustained study of joint disease over 40 years. He wrote about the common and potentially fatal forms of arthritis – tubercular and septic – and his achievement was to draw attention, with admirable clarity, to chronic synovitis that was not fatal, and which could be managed conservatively. He claimed that “a great number of limbs are now preserved which would in former times have been amputated as a matter of course”, a dreadful operation in the days before anesthesia (pp. 99–100).1

Brodie's initial studies of joint disease were presented as a series of papers to the Medical and Chirurgical Society of London.2 His subsequent book, Pathological and Surgical Observations on the Diseases of Joints went through five editions. We reviewed three editions of Brodie's book3 to illustrate his admirably clear descriptions of three types of inflammatory arthritis (Fig. 1).

Reactive arthritis

A gentleman forty-five years of age, in the middle of June, 1817, became affected with symptoms resembling those of gonorrhoea. There was a purulent discharge from the urethra, with ardor urinae and chordee. On the 23rd of June he first experienced some degree of pain in his feet …

June 25th, the pain in his feet was more severe; the tunicae conjunctivae of his eyes were much inflamed, with a profuse discharge of pus. These symptoms increased in violence …The whole of each foot became swollen; there was inflammation of the synovial membranes of the ankles; and … inflammation of the synovial membranes belonging to the joints of the tarsals, metatarsals and toes…

Two days later “the synovial membrane [of the left knee] was found exceedingly distended with synovia …”

Symptoms improved. The patient developed pain in the right elbow and shoulder, without swelling, and mild synovitis of the right knee. “From this time” said Brodie, “he progressively mended …”

… became affected with an ophthalmia, but of a different nature from that which he laboured under in the preceding summer. The inflammation was seated in the proper tunics of the eye; and … [might] have terminated in adhesions of the iris …3a (pp. 55–60)

He never had any return of the inflammation of the synovial membranes or the purulent ophthalmia, but no year elapsed without an attack of acute iritis … [ultimately] the vision in one eye was completely destroyed, while that in the other was very imperfect.3c (p. 46)

This clearly identifies the disease as part of the seronegative sponyloarthritis spectrum.

He described four other cases, all men, in whom a similar train of symptoms took place. All had recurrent attacks, and all had urethritis, asymmetrical arthritis (predominantly of the lower limb), and conjunctivitis, though not necessarily in that order. One patient had three attacks of iritis.

I was led to suspect that the fluid in the joint might be purulent … I punctured the knee with a narrow sharp-pointed instrument; and, by applying a cupping glass over the puncture, drew off between two and three ounces, not of pus, but of turbid serum, with small flakes of coagulated lymph floating in it.3b (p. 62)

The ‘coagulated lymph’ is now called ‘rice bodies’; culture for bacteria did not then exist.

The disease is usually described under the name of gonorrhoeal rheumatism, though it is plain … that it differs from ordinary rheumatism in many essential circumstances; and though … it occurs in most instances as a consequence of gonorrhoea, it may take place quite independently of gonorrhoeal infection.3c (p. 43)

The history of reactive arthritis has been told several times.4, 5 Early observers such as Stoll concentrated upon arthritis occurring as a consequence of dysenteric illness.6 He felt that the arthritis and dysentery had the same cause, differing only in form; to use his words, they were ‘filles de la même mère’. For Harkness, reactive arthritis had a venereal or dysenteric form depending only on whether the causative organism entered via the urethra or the gut.7

The triad of conjunctivitis, urethritis and arthritis became associated with Reiter's name. He had reported a single post-dysenteric case in 1916, during the First World War.8, 9 In 1942, the Americans Bauer and Engelmann suggested using the term ‘Reiter's syndrome’ for this triad.10 By then, Reiter had become president of the Reich Health Office and had sanctioned morally indefensible scientific experiments. In 2007 four rheumatologists, including the same Dr Engelmann, recommended that Reiter no longer be honoured with this eponym.11

Noël Fiessinger and Edgar Leroy described four cases of ‘conjunctivo-urethro-synovial’ syndrome in soldiers, also following dysentery. Their publication appeared a week earlier than Reiter's.12 Among Francophones the triad was soon known as the Fiessinger-Leroy syndrome, with Reiter's name being added only later.

Ankylosing spondylitis

Ankylosing spondylitis has been considered to be a disease of antiquity, but recent radiologic studies of 13 royal Egyptian mummies calls this into question.13 Brodie gives one of the earliest descriptions in English of ankylosing spondylitis in the fifth edition of his book.

In 1841 he was consulted by a 31-year-old man who had pain in the spine “from the neck downwards, but especially the middle dorsal vertebrae” and in the pelvis, aggravated by sneezing. Symptoms had begun “almost imperceptibly” 3 years previously. There was “scarcely any perceptible flexure of the spine, the stooping being apparently confined to the motion of the pelvis on the thigh”. He had lost weight, and had an effusion in the right knee. A year later his spine was in “the same rigid and inflexible state as formerly”. He spent most of his time thereafter in Malta; the state of his spine remained unaltered and he “occasionally suffered from inflammation of the eyes …”3c (pp. 358–61).

Rheumatoid arthritis

The disease is rarely confined to a single joint, and in most instances several joints are affected in succession. Often it shows itself in the first instance in a joint of one of the fingers, which is observed to be slightly enlarged and stiff …Then, one after the other, other joints of the fingers are affected in the same manner. It was to this enlargement of the joints of the fingers that Dr Haygarth gave the name nodosities. The immediate cause of it seems to be a thickening of the synovial membrane; and probably in part an effusion of serum into its cavity …

The progress of the disease is generally very slow, so that many years may elapse before it reaches what may be regarded as its most advanced stage …

In a few instances, after having reached a certain point, the disease becomes stationary, or there may be apparently some degree of improvement. But …I do not recollect any one case in which there was anything approaching to a cure.

In one individual a few joints only are affected …; in another scarcely one joint of the extremities remains in a sound state …

Nevertheless the patient thus afflicted, a cripple, dependent on others for the means of locomotion, may live for years …3c (pp. 241–4).

Conclusion

Some of my happiest hours were those during which I was occupied in the wards, with my pupils around me, answering their inquiries, explaining the cases to them at the bedside of the patients, informing them as to the grounds on which I made my diagnosis, and my reasons for the treatment I employed, and not concealing from them my oversights and errors … even now (many years afterwards) these scenes are often renewed to me at night, and events of which I have no recollection when awake come to me in dreams.1 (p. 185)