Contrast-enhanced spectral mammography (CESM) and contrast enhanced MRI (CEMRI): Patient preferences and tolerance

Abstract

Introduction

Contrast-enhanced spectral mammography (CESM) may have similar diagnostic performance to Contrast-enhanced MRI (CEMRI) in the diagnosis and staging of breast cancer. To date, research has focused exclusively on diagnostic performance when comparing these two techniques. Patient experience is also an important factor when comparing and deciding on which of these modalities is preferable. The aim of this study is to compare patient experience of CESM against CEMRI during preoperative breast cancer staging.

Methods

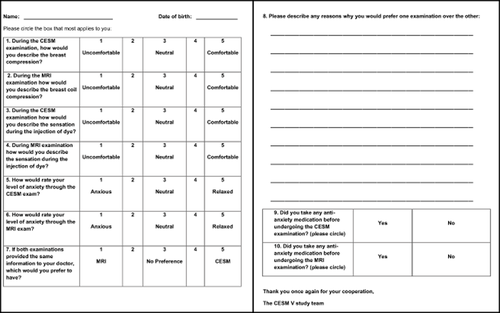

Forty-nine participants who underwent both CESM and CEMRI, as part of a larger trial, completed a Likert questionnaire about their preference for each modality according to the following criteria: comfort of breast compression, comfort of intravenous (IV) contrast injection, anxiety and overall preference. Participants also reported reasons for preferring one modality to the other. Quantitative data were analysed using a Wilcoxon sign-rank test and chi-squared test. Qualitative data are reported descriptively.

Results

A significantly higher overall preference towards CESM was demonstrated (n = 49, P < 0.001), with faster procedure time, greater comfort and lower noise level cited as the commonest reasons. Participants also reported significantly lower rates of anxiety during CESM compared with CEMRI (n = 36, P = 0.009). A significantly higher rate of comfort was reported during CEMRI for measures of breast compression (n = 49, P = 0.001) and the sensation of IV contrast injection (n = 49, P = 0.003).

Conclusion

Our data suggest that overall, patients prefer the experience of CESM to CEMRI, adding support for the role of CESM as a possible alternative to CEMRI for breast cancer staging.

Introduction

MRI is a topic of extensive research and has been described as the most important medical innovation in the last 25 years in a consensus report by general internists.1 In the context of preoperative breast cancer staging, contrast-enhanced MRI (CEMRI) is currently regarded as the most sensitive test for detecting breast cancer. The strength of CEMRI hinges on the use of a gadolinium contrast agent to delineate malignant breast lesions by showing areas of abnormal contrast uptake associated with tumour neo-angiogenesis and the presence of abnormal ‘leaky’ blood vessels.2

Despite strong diagnostic performance, MRI induces a high rate of anxiety-related reactions. Due to claustrophobia, between 1% and 15% of patients having MRI require sedation to undergo the scan or abort it altogether.3 While the use of MRI for breast cancer has been shown to be relatively well tolerated compared with MRI of other body regions,4 compared with conventional mammography, it has been shown to induce a significantly higher level of distress.5 The development of contrast-enhanced spectral mammography (CESM) entices us with the possibility of a non-inferior technique to CEMRI in terms of diagnostic performance and perhaps a better patient experience.6-9

Like CEMRI, the strength of CESM in diagnostic performance relies on the use of intravenous (IV) contrast, though the latter requires administration of iodine rather than gadolinium. CESM offers many possible advantages which may improve patient experience beyond what is possible for CEMRI. Aside from the need for routine IV injection, CESM confers the same logistical advantages that mammography has over MRI, such as quicker procedure time (roughly 10 min), lower cost, absence of need to time the scan according to the menstrual cycle and perhaps most importantly, no associated risk of claustrophobia. As with standard mammography, CESM requires the use of breast compression.

Previous research has focused exclusively on the diagnostic performance of CESM against CEMRI for cancer staging.6, 8, 10 CESM has not yet been confirmed as a valid substitute for CEMRI for this indication, but promising initial results comparing these two techniques have led to more research into this area. No studies as yet have compared the two for patient tolerability regardless of the clinical indication for which the study is performed. Nevertheless, patient experience is an important factor when assessing the overall non-inferiority of CESM relative to CEMRI, and when deciding which of these modalities should be used for patients following diagnosis. Further research is therefore warranted in this area.

Methods

Interim results from 49 participants in the CESM V trial (for protocol, see ANZCTR website11) recruited between June 2013 and November 2014 were analysed. This study aims to assess the diagnostic accuracy of CESM against CEMRI for non-inferiority in the context of breast cancer staging. Patient preference towards either modality forms a secondary objective of this study and is the subject of this report.

Participants were included on this study if they had biopsy-proven invasive breast cancer, were aged 21 years or older and fit to undergo surgery. They were excluded if they had contraindications to IV contrast or MRI, were candidates for neo-adjuvant chemotherapy or had pure in situ carcinoma. Institutional Ethics Committee approval for this study was obtained and all patients provided written informed consent.

All participants underwent both CESM and CEMRI. All CESM examinations were performed with a Senographe DS mammography machine (GE Healthcare, Chalfont St. Giles, UK). All CEMRI examinations were performed with a short-bore (1.6 m) Siemens Sonata Maestro Class 1.5T MRI machine (Siemans Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany). Before their scans, patients were given a participant information sheet describing both procedures. This covered information about what their participation would entail beyond their normal treatment and the benefits and risks of undertaking both of these tests. The order in which CESM and CEMRI were performed was determined by availability of appointments; in 37 cases the CESM was performed first and in 12 cases the CEMRI was performed first. Prior to CESM, 47 participants were administered Iohexol (GE Healthcare Australia Pty Ltd, Rydalmere, NSW, Australia) and two were administered Ioversol (Mallinckrodt Canada ULC, Montreal Parenteral Plant, Point-Claire, Quebec, Canada), at an average dose of 104 mL (SD = 15 ml). The only reason for the difference in contrast used was a change in the infusion pump. All CEMRI participants were administered gadopentetate dimeglumine at an average dose of 15 mL (SD = 4 ml). All patients had both scans at least 24 h apart from one another. This delay was to ensure almost complete clearance of the contrast administered during the first scan before the injection of contrast for the later scan (minimising any risk of contrast-induced nephropathy).

Participants were given a five-point Likert scale questionnaire following completion of whichever of the two modalities they underwent second. The questionnaire contained seven questions about their preference towards aspects of either modality (Fig. 1). All questions were designed to address subjective measures of patient experience of either modality for which CESM and CEMRI could be directly compared: tolerance of the IV dye injection, tolerance of the breast compression and level of anxiety. Study participants also answered which of the two tests they would prefer to undergo if neither was inferior in diagnostic capacity, and were asked to elaborate on reasons for this preference. The number of patients taking anxiolytics prior to either scan was collected for the last 15 participants, once this was recognised by the researchers as a potential confounding variable to patient anxiety during either scan. As not all participants completed all questions, the number of participants reported in the various analyses varied.

Five-point Likert questionnaire relating to participant experience of contrast-enhanced spectral mammography (CESM) and contrast-enhanced MRI (CEMRI).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS version 22. A Wilcoxon sign-rank test was used to compare the responses for CESM and for CEMRI relating to patient experience (questions 1 to 6). Question 7, which addressed overall patient preference for either technique, was measured with chi-squared analysis as this was based on single sample data where preference for one modality over the other was graded along the same Likert scale.

Results

Of the 77 patients who were invited to participate, 68 provided consent and 9 declined to participate. There were 11 participants who withdrew from the study after giving their initial consent as they felt overwhelmed following their diagnosis. A further six participants were withdrawn for the following reasons: one had inadequate renal function, another had a minor adverse reaction to iodinated contrast given during an unrelated CT scan, two developed urticaria 48 hours following the injection of Iohexol for CESM, in one patient IV access could not be obtained and one patient failed to complete the CEMRI scan due to anxiety and claustrophobia. Two participants did not complete the questionnaire so their data have not been included in the dataset. Data from 49 participants were analysed. The average participant age was 55 years (range = 36–74, SD = 9.50 years). The average duration of CESM scans, from the first injection to last mammographic view, was 6 min and 30 s. The average duration of CEMRI examinations, from the time of first to last acquisition, was 29 min and 39 s. There did not appear to be a large difference between the duration in days from the time patients were diagnosed with breast cancer to the time that they had their CESM scan (mean = 7.49, SD = 3.54 days), as compared with the time that they had their CEMRI scan (mean = 11.49, SD = 4.81 days).

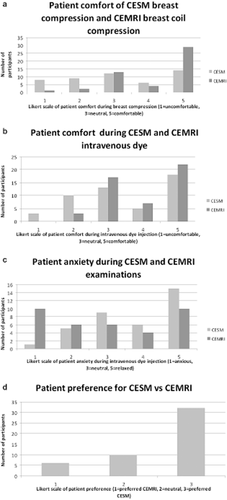

The results of the analysis of the responses to the questions are shown in Figure 2. Significantly more participants preferred CESM to CEMRI (n = 49, P < 0.001). A significantly higher rate of anxiety was experienced among participants throughout the CEMRI procedure compared with CESM (n = 36, P = 0.009). None of the 15 participants questioned regarding the use of anxiolytic medications reported using this type of medication before either scan.

Patient experience of contrast-enhanced spectral mammography (CESM) and contrast-enhanced MRI (CEMRI) in terms of (a) breast compression, (b) intravenous dye injection, (c) anxiety and (d) overall preference.  , CESM;

, CESM;  , CEMRI.

, CEMRI.

Participants consistently preferred CEMRI to CESM for the iodinated contrast injection (n = 49, P = 0.003). Similar data were reported for patient tolerability to breast compression, with participants consistently showing preference towards CEMRI compared with CESM (n = 49, P = 0.001). It is important to note, however, that despite their preferences towards MRI for these factors, the majority of participants reported being either ‘comfortable’ or ‘neutral’ during both the CESM and the CEMRI scan.

Qualitative data were thematically categorised as per recommendations by Polley et al.12 Of the patients who were given these questionnaires, 39 provided clear indication that they preferred one modality over the other. Table 1 summarises participants' reasons for choosing one modality to the other. Many participants cited more than one reason for their preference. The most common reasons for favouring CESM to CEMRI were the relative speed, comfort (standing or lying) and noise of the procedures.

| True for CESM (number of participants) | True for CEMRI (number of participants) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological | Greater speed of procedure | 17 | 0 |

| Less relative noise of procedure | 11 | 0 | |

| Less procedure complexity/More ease | 3 | 1 | |

| Less claustrophobia | 4 | 0 | |

| Less awareness of breathing | 3 | 0 | |

| Less perceived distance between patient and radiographer (i.e. more personal) | 1 | 0 | |

| Greater familiarity (i.e. previous experience of that modality) | 1 | 0 | |

| Immediate access to results | 1 | 0 | |

| Greater confidence in results | 0 | 2 | |

| Less anxiety related to breast compression | 0 | 1 | |

| Less anxiety from IV injection | 0 | 2 | |

| Physical | Greater comfort (mainly due to standing or lying position) | 11 | 4 |

| Less need to remain still | 3 | 0 | |

| Less need for sedation | 1 | 0 | |

| Less discomfort from breast compression | 0 | 1 | |

| Greater accommodation of patient needs (i.e. larger breasts) | 0 | 1 | |

| Less discomfort from injection needle | 0 | 1 | |

| Less sensation from IV injection | 0 | 2 | |

| Less relative pain | 0 | 1 | |

- IV, intravenous; CEMRI, contrast-enhanced MRI; CESM, contrast-enhanced spectral mammography.

Discussion

This study is the first to have compared CESM against CEMRI in terms of patient preference. These findings set a strong platform for future studies by addressing a number of questions which so far have remained unanswered. Firstly, the study has demonstrated that CESM is preferred by patients compared with contrast enhanced MRI performed in a short-bore MRI machine (1.6 m in length). This is important, given that research has demonstrated a reduction in claustrophobia, by a factor of three, when using short-bore machines compared with older long-bore (>1.6 m) models.13

Patient anxiety

Our findings demonstrate that participants experienced aversion to CEMRI for a number of different reasons. Our quantitative data show a lower level of anxiety associated with CESM compared with CEMRI. Only four study participants referenced claustrophobia as a basis for preferring CESM to CEMRI, with the commonest reasons being the shorter relative duration of CESM, greater comfort and lower noise level. Previous research has shown that anxiety reduction protocols can alleviate the psychological impact of MRI on patients. These include giving them information about what an MRI entails before their scan, equipping them with cognitive strategies, giving them a tape recording of the noise from an MRI scanner and allowing them control over music in the scanning room.14 Granted that our trial did not employ any of these strategies (aside from provision of information about what the CEMRI entails), it is possible that when implemented, a combination of these interventions could improve patient tolerability of CEMRI relative to CESM. Therefore, it is recommended that future research examining patient experience of the two study modalities documents the role that these factors may play on patient anxiety associated with either technique.

Contrast injection

Participants reported significantly lower rates of comfort during CESM for the measures of IV contrast injection. While the risk of adverse reactions from either contrast agent has been investigated,9, 15 this is the first study to have investigated how the use of one rather than the other may contribute to overall patient experience. Despite significant preference to CEMRI for this measure, only two participants cited the sensation from the injection of iodinated contrast and the anxiety arising from it as being a defining factor for their preference towards CEMRI.

Breast compression

The decision to include tolerability of breast compression as a criteria for comparison was based on previous research which suggested that pain associated with mammography may undermine compliance with ongoing screening.16 Our findings demonstrated a significant preference with respect to the minimal breast compression associated with breast immobilisation for CEMRI in a breast coil as compared with CESM. This study is the first to investigate this area in the context of preoperative staging, where different factors may have come in to play compared with those found during screening, e.g. the breasts may be more sensitive to compression following recent diagnostic biopsy. However, despite our findings suggesting that participants experience more discomfort due to breast compression during CESM relative to CEMRI, this did not seem to adversely influence their preference towards CESM.

Study limitations

The most important limitation of this study relates to the small sample size. Despite reaching statistical significance for a number of measures, a larger study is needed before conclusions can be drawn about both techniques as to the non-inferiority of CESM relative to CEMRI and their individual roles in routine clinical practice. We did not ask the majority of participants about whether they had taken anxiolytic medication (e.g. oral benzodiazepines) prior to either CESM or CEMRI. The use of anti-anxiety medication may have influenced perceptions of the test experience and if taken for only one of two modalities could have introduced bias. One participant volunteered in free-text comment that she ‘had to take a valium before the MRI … would have been too anxious to go through it otherwise’. This has brought to light the need to systematically assess use of anxiolytic medications for both tests in future research, as this may confound results at the time of completing the study questionnaire for factors such as pain from breast compression and overall anxiety.

Finally, lack of use of a validated questionnaire limits translation of our study findings in comparison with those of others. This study did not use a standardised questionnaire for collecting information relating to participant anxiety, such as the Impact of Event Scale (IES) or the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI).17 Consistency of future investigative research in this area will create greater scope for data linkage and meta-analysis which will further our understanding in this field.

Conclusion

Previous studies evaluating the use of CESM against CEMRI have concentrated exclusively on comparing their diagnostic accuracy and issues such as cost and accessibility. If diagnostic non-inferiority of CESM to CEMRI is confirmed, the results of our study regarding patient preference for CESM will provide further evidence to support the adoption of CESM as an alternative to CEMRI for selected clinical indications.

Acknowledgements

For the first 5 months of this study, GE Healthcare, Chalfont St. Giles, UK, supplied the equipment modifications required to perform the CESM examinations. GE has had no part in the study design and has not had access to the results of this study prior to publication. Funding for this study was received from the Royal Perth Hospital Department of Radiology Special Purposes Account. We also thank the Royal Perth Hospital Medical Imaging Technologists, Biostatistician Mr Michael Phillips and Prof Christobel Saunders for their valuable contributions to this study. Dr Taylor is currently supported by a Harold and Sylvia Rowell Clinician Research Fellowship from the Medical Research Foundation of Royal Perth Hospital.