Mapping competency frameworks: implications for public health curricula design

The authors have stated they have no conflicts of interest.

Abstract

Objectives: We discuss the implications stemming from a recent competency mapping project on public health workforce education and training programs.

Methods: In line with professional practice, we reflected on the results of a major mapping exercise which examined public health competency frameworks against the Global Charter, particularly with respect to the implications for curriculum design.

Results: Our reflections identified five key challenges (diversity of frameworks, interpretation challenges, levels of competence, integration in curricula and knowledge vs skills-based competences) for developing internationally consistent credentialling standards.

Conclusions: While the Charter provides an international benchmark for public health curricula, we argue that applying an international competency framework is challenging. Anyone working in public health should be trained in all foundation areas of public health to support public health practice and initiatives into the future and they may then choose to specialise in sub-disciplines of public health.

Implications for public health: Both theoretical and practical content must be fully integrated across public health programs to operationalise competencies. Utilising the Charter can ensure alignment with the sector needs, and curriculum mapping should be an integral part of a continual and ongoing review process.

Public health competency frameworks provide benchmarks for best practice in public health education and training and provide a potential basis for the sharing of core content across and between programs for equivalence. In many countries they also serve as a measure of competence in professional practice. We draw on the definition of competency provided by Gonzci1 as an integrated set of knowledge, attitudes, values and skills required for intelligent performance for particular situations. Wong2 argues that competency-based learning “promises greater accountability, flexibility and learner-centeredness.”

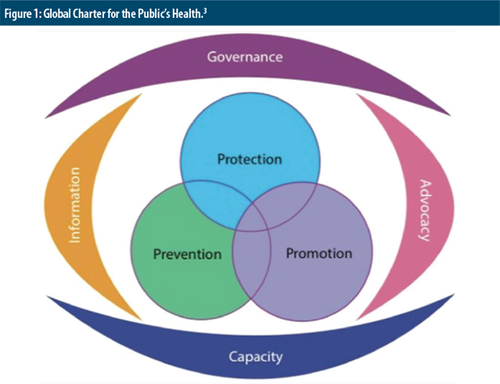

The Global Charter for the Public's Health, developed by the World Federation of Public Health Associations (WFPHA) and endorsed by the World Health Organization (WHO), gives guidance for essential public health services and provides direction on the core functions for the profession (Figure 1).3 The Charter reflects the wide scope of public health practice and provides the foundation for multisectoral policies and collaborations to address contemporary public health challenges.

Global Charter for the Public's Health.3

It has been argued that there is a need for a public health workforce that has the capacity and capability to respond to both local and global emergencies,4 as well as manage routine public health activities including health promotion and disease prevention and protection, in addition to health governance and policy. Such events typically occur because of changes to our physical and political environments and lead to injury to humans and ongoing mental health problems, as well as animal and plant health, and may include:

- Spread of infectious and communicable diseases: such as Cholera, variations of SARS CoVs, Ebola, Avian influenza;

- Naturally occurring disasters: such as the tsunamis in South-East Asia and Japan, earthquakes and volcanic eruptions;

- Effects of climate change: such as the recent bushfires in Australia, California and Greece producing health issues associated with poor air quality, or the sustainability of island nations affected by rising sea levels; and

- Man-made disasters: such as the results of warfare and political disruption, displaced populations, nuclear power plant emergencies, mass shootings and infrastructure collapses.

In order to achieve an effective and internationally proficient workforce, there needs to be provision for cross-national recognition of the public health profession, which requires world-wide standards for public health education.4 With evolutions in the field of education and an increasing focus on competencies as a major driver of curricula design,4 arguably an international competency framework would provide a mechanism for achieving global consistency in educational outcomes. In turn, this would allow for consistent credentialing of public health education programs to achieve the necessary cross-national recognition. This was precisely why the WFPHA Public Health Professionals’ Education and Training Working Group (PETWG) was established in 2010, with one of its goals being to identify and harmonise taught essential public health functions and competencies based on practice needs globally.

As members of the WFPHA PETWG, we recently completed a quantitative mapping of public health competency frameworks to review their alignment with, and contribution to, the current direction set out within the Charter.5 The Charter focuses primarily on public health practice, whereby the seven core elements encompass the diversity of public health functions and services applied at the individual, institutional and governmental levels: public health services (Protection, Promotion and Prevention) and overarching enabling functions (Information, Governance, Capacity, and Advocacy).3 The competency frameworks are used to guide both knowledge and skills for practice, and content of education and training programs. Our work is informing a revision of the Charter to reflect contemporary changes in public health practice.

Our original research5 also identified several implications for public health teaching and learning programs, particularly curriculum design and teaching practices. Furthermore, it highlighted implications for the accreditation of education and training programs and professional registration of public health practitioners, both being mechanisms for professionalising the public health workforce.6 This paper therefore explores these implications for public health teaching and learning programs considering the growing interest in developing consistent credentialing standards for the public health profession.

We note that individual students can gain competence in most of the core services and functions of the Charter, such as skills in managing information systems and knowledge of governance structures in public health. However, not all Charter elements are applicable at the level of individual public health practitioners. For example, if we take the function of capacity, a student cannot be expected to have already meaningfully contributed to broader workforce development. Public health workforce development is important, and public health organisations need to pay attention to credentialing, certification and other markers of professionalism. Therefore, during their education and training students should develop a broad knowledge of workforce development and how related strategies are applied across public health more broadly and demonstrate a personal commitment to continuing professional development and life-long learning.

Methods

Our original mapping review included eight publicly available public health competency frameworks, designed to inform curricula, accreditation standards and/or professional practice standards shown in Table 1. All sets were developed specifically for the discipline of public health, rather than the multiple health profession disciplines that perform public health service functions.7

Competency Framework |

Author |

Aims |

|---|---|---|

European Core Competencies for Public Health Professionals. https://www.aphea.be/docs/research/ECCMPHE1.pdf. Accessed 12 Aug 2019 |

Association of Schools of Public Health in the European Region [ASPHER], 2018∗ |

To inform curriculum development throughout Europe Accreditation |

Foundation Competencies for Public Health Graduates in Australia (2nd ed). http://caphia.com.au/testsite/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/CAPHIA_document_DIGITAL_nov_22.pdf. Accessed 12 Aug 2019 |

Council of Public Health Institutions in Australasia [CAPHIA], 2016. |

To inform curriculum development in MPH and public health undergraduate degree programs in Australia |

Accreditation Criteria – Schools of Public Health and Public Health Programs. https://media.ceph.org/documents/2016.Criteria.pdf. Accessed 12 Aug 2019 |

Council on Education for Public Health [CEPH], 2016. |

Accreditation of schools of public health and public health programs Accreditation |

Core Competencies for Public Health in Canada (Release 1.0). https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/services/public-health-practice/skills-online/core-competencies-public-health-canada/cc-manual-eng090407.pdf. Accessed 12 Aug 2019 |

Public Health Agency of Canada/Agence de la Sante [PHAC], 2008. |

Guide practice of individuals and organisations Inform curricula development, training and professional development |

Generic Competencies for Public Health in Aotearoa New Zealand. https://app.box.com/s/vpwqpz8yyus8d8umucjzbtdi1m111p5u. Accessed 12 Aug 2019 |

Public Health Association of New Zealand [PHANZ], 2007. |

Guide practice of individual public health practitioners Inform curricula development and training |

Public Health Medicine Advanced Training Curriculum. https://www.racp.edu.au/docs/default-source/default-document-library/public-health-medicine-advanced-training-curriculum.pdf?sfvrsn=77252c1a_4. Accessed 12 Aug 2019 |

Royal Australian College of Physicians [RCAP], 2017. |

Outlines expected competencies of public health physicians Inform curriculum development |

Public Health Speciality Training Curriculum. https://www.fph.org.uk/media/2621/public-health-specialty-training-curriculum_final2019.pdf. Accessed 12 Aug 2019 |

UK Faculty of Public Health [UKFPH], 2015. |

Outlines expected competencies of public health registrars Inform curriculum development |

The Global Public Health Curriculum: Revised Shortlist of Specific Global Health Competencies. https://www.seejph.com/index.php/seejph/article/view/1876/1796. Accessed 12 Aug 2019 |

Laaser, 2018. |

Inform curriculum development for postgraduate education and training and professional development of public health professions |

- ∗ Note: The ASPHER competency framework has been significantly updated since this review

Although a full description of the method and quantitative results is provided elsewhere,5 in brief our mapping process involved using a pre-formed template to map the competency statements from each framework against the core elements of the Charter. We then quantified coverage of the Charter's elements in each of the frameworks. Results were collectively compared in a series of discussions. Whilst in general, agreement was easily achieved the process highlighted the complexities and difficulties of undertaking this exercise, given the range of cultural and disciplinary lenses within the team and thus interpretations of the competencies.

Since completing that work, we have undertaken an ongoing iterative process, in line with reflective practice.8 We reflected on the implications that the challenges we experienced have for our own curricula design and teaching practices both individually and collectively, and for other educators from different social and cultural contexts, or different disciplines within the field of public health. Similarly, we reflected on the learning needs of our graduates and the challenges they face applying their theoretical training into effective practice, particularly in times of upheaval. Ultimately, we reflected on how these implications might impact the feasibility of developing internationally consistent credentialing standards.

Results and discussion

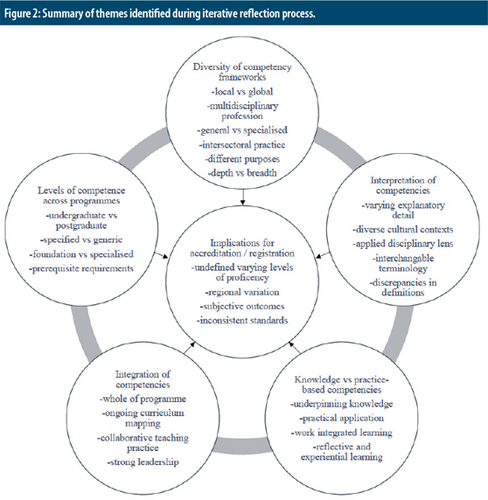

Five key challenges were identified during the competencies mapping process that have implications for developing internationally consistent credentialing standards: the diversity of competency frameworks; challenges in interpreting frameworks; levels of competency required for different programs; effective integration of content to meet targeted learning outcomes; and balancing content based on knowledge versus praxis. Figure 2 provides a summary of these themes and the relationship between the various issues.

Summary of themes identified during iterative reflection process.

Diversity of competency frameworks

While the need for an international competency framework for public health has been considered for some time, achieving this is a major challenge for several reasons. Although public health is recognised as a discrete field, with distinct services and functions,3 unlike clearly delineated clinical-based health professions, public health consists of multiple specialised sub-disciplines9 such as epidemiology, disease prevention or health promotion. As aforementioned, other health professions may also perform specific public health services and functions.4 Public health practice also intersects with multiple other non-health professions4 resulting in sometimes fragmented or siloed education. Tying education outcomes to career pathways can therefore be difficult to evaluate,9 particularly when postgraduate learners are often learning while ‘on the job’.

A wide array of competency frameworks exists which aim to link education to effective practice, both discipline-specific and interdisciplinary public health. Diversity also prevails across and within countries, with different organizations responsible for public health education and training. Some education and competency frameworks are linked to professional standards; others to accrediting agencies.

Accrediting agencies serve, or are discretionarily accessed by, institutions across differing geographical regions.10 When accrediting agencies specify which competency framework must be used, this can impact the taught curriculum, if competencies included in other frameworks are excluded as a result.11 Conversely, which framework is chosen can affect the content and perceived quality of the curriculum11 and may potentially influence decisions made by differing institutions as to which framework their program is accredited against.

Case study:

In Australia there is currently no requirement for public health programs to be accredited. Wishing to have an accredited Master of Public Health (MPH) program, the decision was made by one university to apply for accreditation through the Association of Schools of Public Health in the European Region (ASPHER) rather than the Americas-based Council on Education for Public Health (CEPH), as this framework most closely resembled its existing curriculum.

A study by Harrison, Egemmell and Ereed,11 which used four different frameworks to audit their curriculum, ‘highlights the challenges and effects of selecting any single competence framework against which the curriculum is assessed’. As well as important content variation, they found that inconsistent formatting and terminology used across the frameworks further complicated interpretation of the competencies. Although sceptical of the value of a singular international competency framework, they nevertheless recommend a standard format across all frameworks as a minimum requirement.

Our mapping of eight public health competency frameworks showed that although they remain significantly different in structure, format and levels of detail, the competency sets examined generally do not vary widely; the core content is similar internationally.5 Each set of competencies illustrates the broad nature of public health practice covered in the Charter and in the scope of core competencies that graduates should attain by the end of an educational program. We therefore argue the Charter can be used as a benchmark to achieve global consistency, because it already provides a framework that public health educators can use to review and update their programs so that learning outcomes align with global expectations for public health practice. Mapping the alignment of competencies expected common to all working in public health ensures that graduates can work in an international setting in a variety of public health fields.

However, we must also be mindful of the international focus of the Charter. Fully internationalising curricula risks silencing and marginalising local and culturally diverse perspectives. For example, our research highlighted the absence of culturally responsive practice as a core competency in many of the frameworks and the Charter, particularly in relation to working with Indigenous peoples across the globe.5 Public health learning and teaching must be responsive and reflective of local cultural contexts, alongside global issues and trends. Our mapping study indeed confirmed that each of the publicly available competency sets reflects a locally contextualised view of the wider field of public health, providing the ‘level of heterogeneity and flexibility’ that Harrison, Egemmell and Ereed11 argue is still needed.

As our study also highlighted, the existing public health competency frameworks are geographically limited to the mainly Anglophile regions of the United Kingdom and Europe, Canada and North America, Australia and New Zealand. Outside of these regions, there is seemingly a reliance on academics and education program developers to ascertain content and assess the meeting of competencies. The apparent lack of frameworks designed for use in low-middle income countries is concerning and warrants attention to ensure their ‘particular public health challenges, which require specific approaches for investigation and effective intervention,’ are addressed.11 Arguably, rectifying this by developing additional frameworks will likely add to the diversity that already exists between public health competency frameworks.

Interpretation of competencies

The mapping process also highlighted difficulties in the interpretation of several competencies, with implications for robust alignment between teaching content and practice. While some level of documentation and explanatory detail is provided with some frameworks, it remained difficult to interpret and consider where and how the competencies fit against the elements of the Charter. Our interpretation of the meaning and intent of many of the competency sets was dependent on both reading the background materials and on working group discussions about intended academic content. The working group had several lengthy discussions about our own personal ways of defining and interpreting the terms and concepts used in the frameworks, highlighting potential discrepancies in how some terms are used interchangeably. These challenges are also reflective of the difficulties in mapping competencies within and between national and cultural contexts, because in part, the frameworks reflect the temporal, geographical, and socio-political concerns of their place of origin. Mapping competencies is therefore a professional exercise which requires sound overall knowledge of the public health field, but also the local, social and political contexts, meaning it is not as simple as it sounds.12

This points to ‘blurriness’ in the universal language of public health and discrepancies in definitions of common concepts. Because the terminology varies between countries, the WFPHA PETWG has developed a set of definitions that can be used throughout its membership, to assist in gaining some clarity and shared meaning for educational processes.13

However, this document does not include definitions for the numerous components of the Charter and how these are applied in public health practice. The consequent variation in interpretation of competencies has implications for guaranteeing that content is addressed similarly and that programs will meet defined expectations of the competency frameworks. A universal language that clearly defines the components of public health practice, rather than just listing the components of practice, will work towards avoiding subjective and consequently inconsistent interpretation.

Levels of competencies

The public health discipline currently has two main entry points, through undergraduate and postgraduate training. Whilst traditionally a postgraduate space, there is a growing number of undergraduate public health offerings.14 This scenario is further complicated by the increasing numbers of emerging doctoral public health degrees.4 Competency frameworks that differentiate between the levels of competence required at the various program levels, such as the CEPH15 framework, provide guidance for curricula designers in decisions about which competencies should be taught, but we found that most frameworks do not provide this kind of breakdown. They were either for a specified level,16, 17 or generic in nature for all public health education programs.18-21

In the latter instance, educators must decide which competencies are applicable to which degree level. We also questioned how extensively and accurately the more detailed competency sets can or need to be covered, taught and assessed within a single program.5 There can be challenges around attending to a large set of competencies within a curriculum, especially at the postgraduate level where the duration of the degree is commonly less than undergraduate programs. Varying interpretations of competencies arguably lead to differing applications within public health education programs at differing levels.

Our mapping process thus raises issues regarding the utility of competency frameworks across different levels of qualifications: What are the agreed standards of each level - introductory, developing, mastery? Can we expect a higher level of competency and independent application and practice at postgraduate level? Which competencies are expected of all public health workers? Are there some competencies which reside with higher levels of seniority? There is clearly a need to rethink essential competencies at each level.

An alternative model, reflected in the Council of Academic Public Health Institutions in Australasia (CAPHIA) framework,22 differentiates between generalist and specialist competencies. Although this model partially explains the aforementioned fragmentation and inconsistency in public health curricula occurring worldwide, which has contributed to calls for a single international framework, it is a way to address the inability of individual institutions to cover everything at the desirable breadth and depth. Indeed, Shickle, Stroud, Day and Smith23 argue that “some, if not all, levels of the public health workforce do not need to be trained in all public health competencies”.

Universities can use their individual area of expertise to highlight their specialised skills (for example in epidemiology and biostatistics, public health policy, or health promotion), in this way accommodating the multidisciplinary nature of the public health workforce. For those who have achieved the foundational competencies through pathways such as undergraduate programs or are health professionals from other disciplines that have received some public health education,10 they can choose to further specialise in one of the subdisciplines of public health and receive the in-depth training that enables them to appropriately respond to the specialised kinds of public health emergencies described above at a consultancy/advisory level. Arguably these programs should be at the postgraduate level.

Certainly, not all doctoral public health programs require students to demonstrate competence in all areas of public health, focusing instead on development of the research skills and completion of a thesis on a particular area of interest. However, not all doctoral public health programs require a public health degree as a prerequisite, often merely a health-related qualification and/or equivalent experience.

This potentially means graduates are not fully trained in public health practice as reflected in the elements of the Charter and are therefore not public health practitioners, but specialists in a sub-discipline, such as an epidemiologist. We therefore argue they should be referred to according to that sub-discipline rather than as public health practitioners. Future work needs to focus on determining which foundational competencies are required to meet sector expectations and public health practitioners trained accordingly. Establishing minimum requirements, or levels of competency, would also give space for students to progress and transition through their learning and career stages from broad levels to specialised knowledge.

Integration of competencies

While Mackenzie, Hinchey and Cornforth24 agree that competency frameworks are a useful guide for what programs should cover, they argue that ‘the domains and competencies say little about how to structure curricula or deliver course content to achieve the intended results.’ According to Corvin, Debate, Wolfe-Quintero and Petersen,25 ‘the curriculum must be versatile enough to incorporate emerging problems but scripted enough to ensure foundational competencies are taught in appropriate depth and breadth.’

Our research highlighted the extent to which the detail in competency sets vary in depth and breadth. We argue that the more detailed frameworks pose challenges for curricula designers to include all content in a program. Conversely, ‘frameworks that take the broader approach allow educators more flexibility in adapting the content of their curricula’5, to both local and changing global contexts.

For foundational and generalised programs, the broad and diverse contexts of public health practice warrants that the teaching and learning of public health professionals mirror this. Corvin, DeBate, Wolfe-Quintero and Petersen26 argue that public health curricula should be integrated and flexible to prepare graduates who can respond and engage within a dynamic and changing public health environment. ‘The issues plaguing health globally are multicausal and require integrated, interdisciplinary approaches to create sustainable and effective solutions. An antiquated, traditional and siloed approach to foundational public health courses falls short in adequately addressing these issues.’26 Whilst competencies refer to what is expected to be taught, there are implications here for the pedagogical approaches in delivering this content and how to build flexibility into teaching programs.

The integration of competencies throughout a program, rather than as discrete content modules, better reflects the nature of public health challenges and the philosophy of public health. Ensuring both depth and breadth in coverage requires a systematic integration and implementation of content across a program. Program development requires intentional consideration of integration and use of multiple ways of knowing and teaching to be successful in creating an effective public health workforce.24 This integration requires continuous course review and a high level of collaboration across teaching staff, and commitment to consideration of the bigger picture of the frameworks being applied. Curriculum mapping should therefore be an integral part of a continual and ongoing review process, and not just a one-off activity.

It also demands strong leadership in being mindful of connections between interrelated content and opportunities for robust and purposeful alignment. For example, Coombe, Lee and Robinson27 argue that it is much more meaningful to integrate cultural competence throughout an entire program, rather than a half day workshop, or standalone course. Course developers must consider that learning outcomes and competency may be gained across the whole program, asking how does students’ learning and progression through the program build on knowledge and skills to develop a cohesive set of competencies? Measuring competency across a program would better illustrate students’ synthesis of knowledge and skills.

Case study:

Massey University (Aotearoa New Zealand) has made a commitment to uphold the national treaty, Te Tiriti o Waitangi,a between Indigenous Māori and the colonising British Crown. This goal requires the University to “promote the determination of Māori-led aspirations, active use of Te Reo Māori (Māori language) and the vitality and wellbeing of all people and our environment in order to give full and authentic expression to the eminence of Te Tiriti o Waitangi”.28 As a Te Tiriti o Waitangi-led institution, Massey University's public health programs must embed and enact Te Tiriti o Waitangi. Understanding and addressing health inequities is fundamental to the discipline of public health. Internationally, it is recognised that public health practitioners must have the skills to appraise the effectiveness of past and current public health work in light of continuing inequitable health outcomes, and critically reflect on their discipline's history. The recently restructured MPH program has a stronger focus on producing graduates who are champions and advocates for improving Māori health and wellbeing.

There are three main ways that Te Tiriti o Waitangi has been integrated in program development:

- The new graduate profile explicitly states Te Tiriti-led practice, partnering with Māori as Tangata Whenua, and working effectively with a range of groups, values and worldviews including with Pacific Peoples.

- Ensuring that the Māori Health course is part of the compulsory core for the PGDipPH and the MPH.

- Including at least one learning outcome in every core course related to Te Tiriti o Waitangi, Māori and Pacific health, and/or Indigenous knowledge.

This approach also links with wider work within the public health sector, improving Māori and Pacific student success, and building Indigenous research capacity and responsiveness. The proposed MPH program has been co-developed and is delivered in partnership with Māori, in order to contribute to advanced health outcomes for Māori communities.

Knowledge vs practice-based competencies

Beyond deciding on appropriate academic content, public health programs must also be designed for practical competence. This requires an additional focus when applying competency frameworks beyond imparting knowledge, to integrating skills and applied exercises to meaningfully prepare students for engagement in public health practice. The ability to perform tasks, or competencies, requires practice and experience. Teaching and learning play a key role in operationalising the competencies – moving the students from theoretical knowledge to practical application.

The service-learning model, when implemented well, is a practice designed to foster transformative student and community development. Students engage with community partners and are challenged to critically self-reflect, synthesise, and apply their public health learning, analyse ethical and civic situations, and, in partnership, work toward community action.24

Creativity in this space allows application of knowledge to real world settings and local contexts to generate a workforce capable of dealing with public health challenges locally and globally. For this reason, we found those frameworks that include practical examples for application in curricula most useful, as this also goes some way to addressing the question of how curricula should be delivered, particularly when it comes to praxis courses. For instance, the UKFPH16 framework provides examples of work undertaken by Public Health Specialty Registrars that are mapped against the key areas of public health competence. For institutions wanting to adopt a flipped classroom and experiential learning model that utilises practice exercises,25 such examples could be used to inform the design of their classroom activities or assignments.

The pre-existing mapping of examples against the core competencies also addresses challenges associated with interpretation of the competencies by individual educators and curricula designers,11 particularly given the multidisciplinary nature of public health.5 As public health is a practical discipline, suggestions within frameworks for practical application are helpful in understanding specific competencies.

Implications for accreditation and registration

The variations between levels of competencies, how these are applied across different programs and what qualifications are thus awarded, have implications for program accreditation and practitioner registration or licencing. As aforementioned, the two competency frameworks used for the education of public health physicians outline competencies expected for a specified program of study, rather than differentiating between degree levels. Nevertheless, they outline different levels of competency to provide an indication of progress towards the minimum level of competency expected to be achieved, to become registered as a public health physician. While the UKFPH16 framework requires graduates to achieve a ‘full’ level of competency to become registered as locum consultants, the RACP17 framework recognises that the public health field is very broad and hence does not expect physicians to be an expert in all competencies. Instead, it dictates what the minimum expected level for each competency is and indicates more advanced levels to inform self-directed continuing professional education. Credentialing in these cases is relatively clear cut.

Given the CEPH15 framework clearly distinguishes between the various levels of competencies expected at each program level making accreditation requirements explicit, it would arguably also make accreditation expectations clear. Yet programs in the United States of America have completely different structures, meaning accreditors are still required to make subjective judgements in awarding their credentials. As we have found, interpretation is not necessarily straight forward. Frameworks that do not differentiate between competencies required for each program level similarly require accreditors to make subjective judgements.

This is further complicated by variations in credentialing standards across nations,4 different accrediting bodies serving different regions10 and various discipline-specific or sub-specialty areas having separate accreditation bodies with differing credentialing standards.9 For example, health promotion programs may be accredited by national accrediting organisations using their local competency framework, such as the Australian Health Promotion Association,30 or using the International Union for Health Promotion and Education31 core competencies. Furthermore, public health education programs can choose to be accredited by both public health and sub-specialty bodies.

The need for localised versus standardised global curricula is not likely to change soon, which makes the opportunity to use the Charter as an international benchmark more critical. The PETWG is therefore currently undertaking two key pieces of work; firstly, to develop a globally relevant public health competency framework that incorporates the needs of low-middle income countries and clarifies what should be expected as foundational public health competencies; and secondly, to establish a mechanism for endorsing locally contextualised public health competency sets designed for accreditation purposes, which contain all elements of the Charter.

In this way, public health education programs seeking accreditation will need to provide a program of learning in which students are introduced to all core areas of public health, providing graduates with a means of demonstrating competence in all elements of public health practice. Should universities decide to pick and choose the areas they wish to teach and avoid core areas (for example, biostatistics, health policy theory, or health promotion) they are arguably not teaching a public health degree. We would argue they should instead describe it as either a degree specific to a specialised sub-discipline or a generic degree in health sciences.

Conclusions

Although we completed the mapping work outlined in this paper before the SARS CoV-2 pandemic, it has caused many jurisdictions to rethink and appropriately resource their public health capacities. Outcomes from our study have important implications for public health workforce education and training to support public health practice and initiatives into the future.

Competency frameworks are commonly used to structure public health education programs and are central to ensuring that the future public health workforce gain the core competencies expected to enable them to work effectively to address emerging public health challenges. Public health competency frameworks traditionally applied to postgraduate specialised MPH programs. However, given the increasing number of broad undergraduate public health programs, and specialist postgraduate and doctoral programs, it is timely to consider the knowledge and skills that are expected at each level, to ensure tomorrow's public health workforce is appropriately educated and trained to flexibly respond to emerging public health challenges. We argue that anyone working in public health should be trained in all foundation areas of public health, in an accredited public health education program, but may then choose to specialise in one of its sub-disciplines.

In this paper we have reflected on our competency mapping process assessing several competency frameworks against the Charter. Although an international framework would be useful for setting a global standard, there is still a need for local adaptations which address national and regional contexts. However, the Charter provided a useful mechanism to compare competency sets, and to assess public health program content. The Charter could therefore provide additional usefulness in program (re)design to ensure alignment with overarching sector expectations. Hence, an endorsement mechanism for those frameworks that align with the Charter will ensure that public health education and training programs accredited against these frameworks will need to cover all core areas of practice.

A curriculum based on competencies helps to ensure that students gain both requisite knowledge and skills for effective praxis. However, the integration of theory and practice-based content must occur in tandem, and competencies need to be integrated throughout programs, rather than as content modules. We suggest that programs which use multiple ways of knowing and teaching are likely to be more successful in creating an equipped public health workforce. Frameworks that provide practical examples and experiences of practice will assist curriculum designers and educators to better interpret competencies and provide the experiential learning experiences graduates need to develop praxis.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the development and leadership work of Dr Linda Murray (Massey University, New Zealand) as co-director (with Dr Christina Severinsen) of the Massey University Master of Public Health program.