Introduced and extinct: neglected archival specimens shed new light on the historical biogeography of an iconic avian species in the Mediterranean

Abstract

Collection specimens provide valuable and often overlooked biological material that enables addressing relevant, long-unanswered questions in conservation biology, historical biogeography, and other research fields. Here, we use preserved specimens to analyze the historical distribution of the black francolin (Francolinus francolinus, Phasianidae), a case that has recently aroused the interest of archeozoologists and evolutionary biologists. The black francolin currently ranges from the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East to the Indian subcontinent, but, at least since the Middle Ages, it also had a circum-Mediterranean distribution. The species could have persisted in Greece and the Maghreb until the 19th century, even though this possibility had been questioned due to the absence of museum specimens and scant literary evidence. Nevertheless, we identified four 200-year-old stuffed black francolins—presumably the only ones still existing—from these areas and sequenced their mitochondrial DNA control region. Based on the comparison with conspecifics (n = 396) spanning the entirety of the historic and current species range, we found that the new samples pertain to previously identified genetic groups from either the Near East or the Indian subcontinent. While disproving the former occurrence of an allegedly native westernmost subspecies, these results point toward the role of the Crown of Aragon in the circum-Mediterranean expansion of the black francolin, including the Maghreb and Greece. Genetic evidence hints at the long-distance transport of these birds along the Silk Road, probably to be traded in the commerce centers of the Eastern Mediterranean.

INTRODUCTION

Biological collections represent an invaluable source of information in a plethora of research fields, including historical biogeography and conservation biology (Holmes et al. 2016). Over the last few decades, museum specimens have been widely used to produce genetic data for taxa that are rare (Costa et al. 2017) and/or distributed across areas with difficult access (Tae-Woo & Puskás 2012; Masseti 2012; Monteiro et al. 2017; Guerrini et al. 2020). Despite the ethical issues recently raised by some authors (cf. Russo et al. 2017), the genetic material extracted from conserved skins and stuffed animals—often referred to as archival DNA—has been used for conservation management (for instance, to identify genetically close source populations to restore extinct ones: Haouchar et al. 2012) and to assess the otherwise secretive ancestral genomic makeup of intensively managed taxa prior to the onset of restocking practices (Nielsen et al. 1999; Ruzzante et al. 2001; Hauser et al. 2002; Barbanera et al. 2010, 2015). Material from historical biological collections has also been key to investigating vanishing and extinct taxa (e.g. Higuchi et al. 1987; Cooper & Hull 2017; Feigin et al. 2018) and to measure the admixture proportions between domestic species and their wild ancestors (e.g. Wu et al. 2020, 2023), as well as to properly assess the seldom underrated past human impact on present-day biodiversity (e.g. Meineke et al. 2019; Oswald et al. 2023). The many applications of archival DNA studies rely on the spatial and temporal biogeographic representativeness of sample collection, for which the often neglected small exhibits and private collections may become precious sources (Casas-Marce et al. 2012). Noteworthy, citizen science often represents a useful tool for locating such valuable specimens (European Commission 2013).

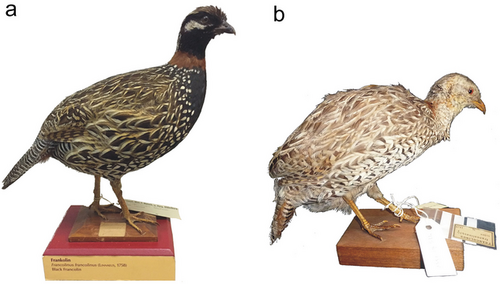

In this paper, we present the iconic case study of the black francolin (Francolinus francolinus Linnaeus, 1766) (Fig. 1; Figs S1,S2, Supporting Information), a medium-sized game bird that has recently aroused the interest of archeozoologists and evolutionary biologists. This taxon belongs to a radiation of five poorly known eastern Palearctic congeners whose evolutionary relationships were clarified only a decade ago (Forcina et al. 2012). The black francolin is the most widely distributed species of that group, currently ranging from Cyprus to the Indian subcontinent with six morphological subspecies (Forcina et al. 2014; McGowan & Kirwan 2015), even though mitochondrial DNA supports only three well-defined genetic groups, each one corresponding to a pair of the traditional subspecies (Forcina et al. 2012, 2015). Moreover, both microsatellite DNA (Forcina et al. 2019) and vocal data (Boesman 2019) support only two groups consisting of the two westernmost and all the other four taxa, thus calling for a reappraisal of the intraspecific taxonomy, which goes beyond the purpose of the present study. The three mitochondrial DNA groups are ascribed, respectively, to the areas stretching i) from the Eastern Mediterranean across the Middle East and the Caucasus up to northern Iran; ii) from the Persian Gulf to Afghanistan and part of Pakistan (but see Forcina et al. 2018); and iii) from the rest of this country to Bangladesh across the Indian subcontinent (McGowan & Kirwan 2015). However, iconographic and literary evidence indicate that the black francolin had also a circum-Mediterranean distribution at least since the Middle Ages (Masseti 2009; Oriani 2014) and that it could have survived in some areas therein until the 19th century (Lilford 1862; Maluquer & Travé 1961). A study of modern samples and archival specimens unveiled the non-native status of the extinct populations from Sicily, central Italy (Tuscany), and Spain, and pointed to the Near East and the Indian subcontinent as the two sources of distinct introduction events to the Western Mediterranean (Forcina et al. 2015).

Here, we address the controversial historical presence of the black francolin in Northern Africa and Greece. Several authors had noted the occurrence of this species in the Maghreb (AA VV 1784; Mouton-Fontenille 1811; MacCarthy 1850; Chenu 1851; Brehm 1870; Chevreux 1891; Ogilvie-Grant 1896; Arrigoni Degli Oddi 1902), but this information was discredited by others (Arrigoni Degli Oddi 1929; Lavauden 1936). Conversely, the past occurrence of the species in Greece has never actually been called into doubt, but no preserved specimens had been identified prior to the present study. The black francolin had been reported from the Greek mainland (Chenu 1851; Annales de la Société d'histoire naturelle de Toulon 1910); from the islands of Lesbos, Samos, and Rhodes (Tournefort 1717; Brisson 1760; Mouton-Fontenille 1811; Annales de la Société d'histoire naturelle de Toulon 1910; Handrinos & Akriotis 1997); or from unidentified Aegean islands (Hume & Marshall 1879–1881), until the first half of the 19th century (Lilford 1862). The former occurrence of the black francolin in Crete was contentious according to Pliny the Elder (as reported in Buffon 1820), but deemed possible by more recent authors (Tristram 1884; Masseti 2009). Interestingly, since all the literature records mentioning the black francolin in the Latin world (where it is always referred to by its Greek name, Attagen or Attagas) date back to after the Roman conquest of Greece, the popularity of this bird was deemed to be part of the broader process of grecianization of Roman customs and traditions (Oriani 2014).

In this study, we identified black francolin museum specimens—presumably the only ones still available—from the Maghreb and Greece and genotyped them at a mitochondrial DNA control region fragment. Our goal is to assess the genetic affinity of the new samples, helping to better understand the nature of the historical presence of the black francolin around the Mediterranean.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We retrieved four black francolin museum specimens sampled from the extinct populations once inhabiting Algeria (n = 2), Greece (n = 1), and one unspecified locality in southern Europe (n = 1) (Table 1). Total genomic DNA extraction and the amplification of a 185-bp fragment of the mitochondrial DNA control region was performed as in Forcina et al. (2015) in a dedicated clean room for the processing of archival samples at the Centre for Molecular Analysis (CTM) of CIBIO/InBIO (Portugal). The workflow was conducted in strict conformity to ancient DNA protocols throughout all steps, including the incorporation of DNA extraction and PCR blank controls to check against possible contamination. PCR amplicons were then visualized on 3.0% agarose gels stained with GelRed and purified following a standard ExoSAP protocol (Fermentas Life Sciences, Waltham, MA, USA) prior to direct sequencing of both DNA strands (BigDye Terminator v.3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit, ABI 3730 DNA automated sequencer, Applied Biosystems, USA) at CIBIO/InBIO. The control region fragments were aligned with ClustalX v.1.81 (Thompson et al. 1997) along with a number (396) of homologous sequences obtained in previous studies of authors of this research (n = 302) as well as of others (Kumar et al. 2020; Negi & Lakhera, unpublished: n = 94) (Supporting Information S1 and S2) to achieve a thorough coverage of the current and historical range of the species. We hence imported the generated nexus file into DnaSP v.5.10.1 (Librado & Rozas 2009) and exported it in the RDF format used for building a haplotype network with the median-joining method (Bandelt et al. 1999) as implemented in NETWORK v.5.0.1.1 (Fluxus Technology) by weighting uniformly mutated positions while setting the ε-tolerance parameter and the transitions/transversions ratio to 0 and 1, respectively.

| Voucher, Sex | Museum, Town, Country | Collection site | Collection date |

|---|---|---|---|

| AVE425, M | State Museum Nature and Human Oldenburg (Landesmuseum Natur und Mensch Oldenburg), Oldenburg, Germany | Greece | before 1895 |

| MZS Ave01336, M | Strasbourg Zoological Museum (Musée Zoologique de l'Université et de la Ville de Strasbourg), Strasbourg, France | Algeria | 1842 |

| MZS Ave01339, M | S Europe | 1832 | |

| MZS Ave01340, F | Algeria | 1842 |

- M, males; F, female; S, southern.

RESULTS

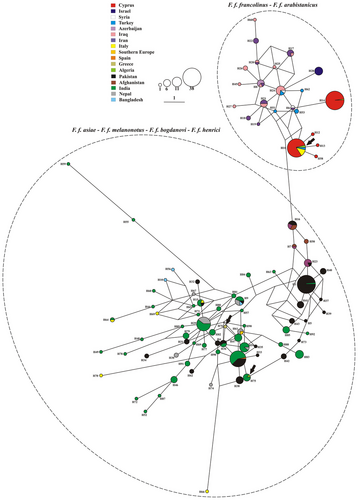

The alignment of the (4 + 396) 400 control region sequences defined a set of 186 characters including indels and 52 variable sites. Ninety-three haplotypes were found (H1–H93: Table S1, Supporting Information).

The network supported the genetic structure already identified by previous studies (Forcina et al. 2012, 2015, 2018), roughly corresponding to three - arguably two - lineages (Fig. 2; see also the Bayesian tree in Forcina et al. 2015). One of the new samples (from Algeria), fell within the group composed by the westernmost subspecies, having the same haplotype (H11) as conspecifics from Cyprus, Turkey, and Italy (both Sicily and Tuscany). The other three samples belonged to the other group, including all the other subspecies. One Algerian sample and the Greek one had haplotypes that coincided (H75) or were close (H76) to those described from Uttarakhand (northern India). Finally, the sample from an unidentified southern European location (Table 1) yielded the same haplotype (H61) of three individuals from Nepal.

DISCUSSION

Black francolin historical biogeography: toward a far more complete picture

The interplay of sedentarity and strong habitat fidelity along with the remarkable longitudinal and latitudinal extension of its distribution make the black francolin an ideal subject to investigate the biogeography of Palearctic fauna (Forcina et al. 2019a). Nonetheless, key pieces to obtain a comprehensive picture of the diversification of this species are still missing. The genetic investigation of modern and historical black francolin samples added another tile in understanding the deep impacts of biological globalization in the Mediterranean region, clarifying the nonnative nature of the populations once inhabiting Italy and Spain (Forcina et al. 2015). The present study corroborates the role of human-mediated dispersal in relation to the historical presence of the black francolin across most of the Mediterranean regions. The newly genotyped samples fell within the previously identified mitochondrial lineages, ascribed to either the Near East or Indian subcontinent (Fig. 2). At the same time, these results—along with the absence of archeozoological records—ultimately disproved the possible persistence of an allegedly native westernmost subspecies in Greece and the Maghreb until the beginning of the 19th century, which prompts the questions of who and when had introduced the black francolin to those areas.

There is abundant literary and iconographic information on the use of the black francolin as a culinary delicacy possessing medical and aphrodisiac properties in the ancient Greek and Roman world (Thompson D'Arcy 1895; Borghini et al. 1983), as well as in Medieval and Renaissance Europe (Baldacci 1964; Cosman 1983; Masseti 2002, 2009; Adamson 2004), with several documents describing it as a courtly game bird kept in high regard by the ruling elites in western Europe, especially in Italy and Spain (Forcina et al. 2015, 2019b). For instance, when the Spanish King Philip V visited Leghorn in 1731, Gian Gastone de' Medici, the last Medicean Grand Duke of Tuscany, paid him homage with “200 among francolins, partridges and quails,” among other things (Vivoli 1846). The presence of the black francolin in Spain is documented in at least 70 historical literary sources, including even some authored by Quevedo and Cervantes. Mentions are concentrated within or nearby the Crown of Aragon, where the black francolin was most often considered a majestic game species (Jiménez Pérez 2013) appearing in documents related to Aragonese kings Jaume I (1208–1276) (Chapman & Buck 1910) and Pere IV (1319–1387) (Maluquer & Travé 1961). Some of these documents are hunting bans mentioning monetary fines and even harsh corporal punishments for those who attempted to hunt and sell this extraordinary quarry, whose consumption was meant to be exclusive for high-borne people (as in the case of the Compilacion de Canellas o de Huesca from 1247 and the Constitucions de Cathalunya from 1456: Jiménez Pérez 2013). Other historical documents are letters explicitly revealing the intention of boosting the existing populations of this species or establishing new ones. For instance, in a letter sent to the commander of Lorquí (Murcia Province), Sancho Dávalos, in January 1454, the king of Castile Juan II asks for a dozen black francolins, six males and six females, with the obvious intent of multiplying them for consumption (Torres Fontes 1974). In the 16th century, King Felipe II bred black francolins in the royal gardens (Sitios Reales; see Clavero 2022) and repeatedly received bird shipments from Murcia (34 individuals from Cartagena, May 1562; AGS LEG 251:2 Fol 13) or Valencia (70 birds, January 1565; AGS LEG 252.3 Fol 86). There is also documentary evidence of the transport of the black francolin outside Iberia. A letter sent by King Pere IV of Aragon from Sicily to the governor of Mallorca in 1368 mentions the black francolin as one of the several game birds imported to the island.

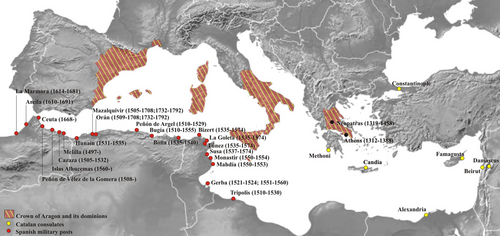

The historical distribution of the black francolin across the Mediterranean strongly resembles the areas of influence of the Crown of Aragon (Fig. 3). In the late Middle Ages Aragon had become the most powerful Mediterranean thalassocracy (Abulafia 2014) controlling several commercial routes and, particularly, the connection of the Silk Road with Western Europe through Eastern Mediterranean trade centers (Coulon 2017). It seems thus plausible that the black francolin primarily and mostly expanded across the Mediterranean transported by Aragonese ships, as already pointed out by Maluquer and Travé (1961). This transport would have had its origin in the Eastern Mediterranean trade hubs and would have involved both birds native to that area as well as those brought there by the Silk Road caravans, resulting in the admixture of genetic lineages found in historical Mediterranean samples characterized in this study and in previous ones (Forcina et al. 2015).

Portuguese fleets—which played a major role in importing exotic fauna to Europe from the late Middle Ages onward (Simões 2014, 2021)—could also have had a role in the human-mediated dispersal of the black francolin. This transport would have been associated with the Silk Route of India, a trade route connecting the Khyber Pass, at the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan, with the Indian Ocean along the Ganges River (Sarkar 1927; Wiles 1972). This area was controlled by the Portuguese, for which Calcutta and Dhaka were crucial emporia in the East (Campos 1919; Alam 2018). However, the lack of historical black francolin records in Portugal or Portuguese-dominated territories and the late establishment of this route in comparison with the appearance of the species in the Western Mediterranean suggest that the role of Portuguese fleets in the expansion of the black francolin would have been minor, if any.

The presence of the black francolin in the Maghreb might be related to the pan-Mediterranean dominant status of the Crown of Aragon. The Hispanic presence increased in the area after the conquest of the Kingdom of Granada, in 1492, when the Catholic Monarchs established a system of fortifications along the Mediterranean African coast. This ambitious project, which started with the conquest of Melilla and Orán under Ferdinand II of Aragon, was carried out forward by his successors, who expanded the Spanish dominions eastward to Tripoli with the ultimate goal of establishing a route to the gold of Sudan and Ethiopia as well as to the spices from India and the Far East through the Red Sea (Bal 2011). Such a process reached its peak with Charles V, who presented himself as the leader and the paladin of the Catholic Christian world against the Islamic one in the framework of more than a century-long clash between the Spanish and the Ottoman empires (Arıkan 1995).

However, while the role of Spain behind the importation of exotic fauna to Europe and the Mediterranean in the Renaissance was prominent (Pérez de Tudela & Jordan-Gschwend 2007), the occurrence of black francolins of southern Asian origin in Greece is also likely associated with the Crown of Aragon, as already suggested by Maluquer and Travé (1961). In this respect, it is worth mentioning that the Almogavars—mercenary troops whose intervention was invoked by Byzantine emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos to fight the rising threat posed by the Ottomans to his dominions—ended up raiding Anatolia and Greece, where they established the Duchies of Athens and Neopatras, which remained over Aragonese rule until 1435. The lasting presence of Iberian mercenaries and their aristocratic leaders in this area might hence well account for the presence of black francolins of southern Asian origin in Greek territory. Taken together, the results of this study finally disprove the still plausible former occurrence of a native subspecies in the westernmost portion of the black francolin range, and further confirm the role of human-mediated dispersal in relation to its historical presence in the Mediterranean.

Concluding remarks

Molecular techniques for DNA extraction and genotyping of historical material are burgeoning (Shapiro & Hofreiter 2012), and emerging next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies allow retrieving massive amounts of genomic data from archival specimens (Woods et al. 2017), with modern cloning approaches even opening the possibility of species revival from extinction (Kumar 2012; Redford et al. 2013; Shapiro 2017). Nevertheless, short single DNA fragments amplified by Sanger sequencing can be obtained quickly and cheaply—as opposed to massive NGS data—while still delivering preliminary information, which is key to redirecting the ongoing efforts and available funds. Importantly, these time- and cost-effective exploratory analyses may unmask glaring errors about taxon identity and origin of museum specimens, which, if not readily flagged, may jeopardize the outcome of the research (Boessenkol et al. 2010). As a case in point, the unique archeozoological remains (i.e. a coracoid and a metatarsus dating back to the first half of the 13th century) allegedly belonging to the black francolin from the Western Mediterranean (Sarà 2005) were disproved as such, being instead assigned to the Sicilian rock partridge (Alectoris graeca whitakeri) based on their control region sequence (Forcina et al. 2015).

Our study also testifies to the importance of exploring exhaustively the available museum resources to draw reliable conclusions, which is particularly important in studies addressing the historical biogeography of a given species. Large biological collections may have multiple specimens, which nonetheless are often retrieved during the same expedition and/or from the same site(s). In this scenario, small exhibits and private collections often host unique specimens in terms of origin and time, while access to and examination of grey literature may provide key information to give value and take advantage of these resources. A paradigmatic example of the great effort needed to localize all the specimens of an extinct taxon scattered around the world is offered by the International Thylacine Specimen Database (www.naturalworlds.org/thylacine/mrp/itsd/itsd_1.htm), which is designed as a freely accessible academic tool to better the understanding of the causes underlying the extinction of the Tasmanian tiger or thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus). In the case of F. francolinus, we found that single biological collections may be the sole repository of specimens—sometimes limited to a single exhibit—from a given extinct population.

Other than highlighting the importance of a thorough exploration of all the biological material associated with a given species, corroborating its taxonomic identity and origin using preliminary genetic analyses, this study shows how crucial the role played by even relatively small biological collections can be in zoological research. Indeed, by hosting specimens that are unique in terms of sampling date and locality, these collections are the last custodians of information that would otherwise be irretrievable and that, for this reason, is invaluable. What is even more interesting is that in cases like the one shown here, collection managers might even be unaware of the uniqueness attached to some of these specimens. This often applies also to private collections, including those that are hosted in convents and monasteries scattered around Europe. We call for the creation of an online public database of private collections hosting biological material for the benefit of biodiversity studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the curators of the ornithological collections, their collaborators, and related museums acknowledged by Forcina et al. (2015) along with the people mentioned in Forcina et al. (2012) for the collection of modern black francolin used for comparison in this study. Aleem Ahmed Khan (Bahauddin Zakariya University) and Imran Khaliq (Ghazi University) are acknowledged for sampling in Pakistan, while CTM technicians Susana Lopes, Patricia Ribeiro, and Sofia Mourão for their valuable assistance with Sanger sequencing and their qualified laboratory work. Finally, we are grateful to Panicos Panayides (Game and Fauna Service, Ministry of Interior, Cyprus) for the bibliographic material on the historical occurrence of the black francolin in Greece and Prof. Carlos Martínez Shaw (Real Academia de la Historia) for his assistance in finding historical evidence testifying the trade in black francolins across the Spanish Empire.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data generated in this study have been reported within the main text or in the supporting information. The Control Region sequences produced in this study were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers OR095509-OR095512.