Indigenous food sovereignty assessment—A systematic literature review

Funding information: Open access publishing facilitated by Bond University, as part of the Wiley - Bond University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Abstract

Aims

The aims of this systematic review were to (1) identify assessment approaches of Indigenous food sovereignty using the core domains of community ownership, inclusion of traditional food knowledge, inclusion/promotion of cultural foods and environmental/intervention sustainability, (2) describe Indigenous research methodologies when assessing Indigenous food sovereignty.

Methods

Guided by Indigenous members of the research team, a systematic review across four databases (Medline, Embase, CINAHL and PsycINFO) was performed. Studies in any language from 1996 to 2021, that used one or more of the core domains (identified from a recent scoping review) of community ownership, inclusion of traditional food knowledge, inclusion/promotion of cultural foods and environmental/intervention sustainability were included.

Results

From 20 062 records, after exclusion criteria were applied, 34 studies were included. Indigenous food sovereignty assessment approaches were mostly qualitative (n = 17) or mixed methods (n = 16), with interviews the most utilised (n = 29), followed by focus groups and meetings (n = 23) and validated frameworks (n = 7) as assessment tools. Indigenous food sovereignty assessment approaches were mostly around inclusion of traditional food knowledge (n = 21), or environmental/intervention sustainability (n = 15). Community-Based Participatory Research approaches were utilised across many studies (n = 26), with one-third utilising Indigenous methods of inquiry. Acknowledgement of data sovereignty (n = 6) or collaboration with Indigenous researchers (n = 4) was limited.

Conclusion

This review highlights Indigenous food sovereignty assessment approaches in the literature worldwide. It emphasises the importance of using Indigenous research methodologies in research conducted by or with Indigenous Peoples and acknowledges Indigenous communities should lead future research in this area.

1 INTRODUCTION

There are an estimated 370 million Indigenous Peoples living around the world.1 The term Indigenous, includes the First Nations or First Peoples, Tribes, Aboriginal Peoples and ethnic groups from different countries.2 The Oxford dictionary describes Indigenous people inhabiting or existing in a land from the earliest times or from before the arrival of colonists. ‘Indigenous’ is an umbrella term for First Nations (status and non-status), Métis and Inuit. ‘Indigenous’ refers to all these groups, either collectively or separately and is the term used in international contexts, for example, the ‘United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples’. Colonisation is invasion: a group of people taking over the land and imposing their own culture on Indigenous people. Colonisation is cultural and psychological in determining whose knowledge is privileged. Therefore, colonisation not only impacts the first generation colonised but creates enduring issues.3 Decolonisation seeks to reverse and remedy this through direct action and listening to the voices of First Nations people.

Over the years, communities and organisations have been working towards decolonisation, to reclaim the rights of First Nations Peoples on the access to their land, natural resources and food sovereignty.3 Food sovereignty can be defined as ‘the right to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems’.4 The definition of food sovereignty has evolved over time,5 and while food sovereignty has a historical basis, its current use and terminology was introduced at the World Food Summit by the La Via Campesina Group in 1996.4 Indigenous food sovereignty is a term that has developed from traditional Indigenous knowledges, belonging to First Nations Peoples around the world.6 Indigenous food sovereignty can be defined as ‘a rights-based approach to land, food and the ability to control a production system that emphasises accountability to holding culturally, ecologically and spiritually respectful relations—with plants, animals, environment and surrounding communities within those systems’.7 Indigenous food sovereignty in practice can be seen as a resurgence of Indigenous forms of authority and autonomy around food.8

Assessment of Indigenous food sovereignty is an essential component of reclaiming food sovereignty as it examines the current community food environment, informs change to strengthen food systems, and in turn, community health and wellbeing.9 In research, it is important to support descriptions of Indigenous food sovereignty in the literature to aid in the assessment of Indigenous food sovereignty. However, the assessment presents challenges, including the ambiguity of the term, the lack of availability in peer-reviewed literature, culturally appropriate quality assessment tools to appraise research, the lack of description in assessment methods, including tools and frameworks, and limited research conducted by or with Indigenous authors.7 A recent scoping review identified four common domains that are used to describe Indigenous food sovereignty including: (1) community ownership, (2) inclusion of traditional food knowledge, (3) inclusion and promotion of cultural foods and (4) environmental/intervention sustainability.7 The first domain relates to the degree to which the community is involved in the intervention. The second domain relates to the extent which traditional food knowledge is emphasised as part of the intervention. This includes generational knowledge passed down from Elders and other knowledge keepers, storytelling, and honouring Indigenous ways of planting, cultivating, harvesting, processing and preparing Indigenous foods. The third domain relates to how traditional cultural foods are included in the intervention. The fourth domain relates to Indigenous peoples' ecological responsibility to grow and process foods in an environmentally responsible way, as well as the responsibility of the researchers to conduct research in a sustainable way.7 These domains may be a useful guide to reduce ambiguity of the term Indigenous food sovereignty and assist researchers to assess Indigenous food sovereignty in the literature.

One method that assesses Indigenous food sovereignty is the Food Sovereignty Assessment Tool, developed by First Nations Development Institute, in the USA.10 The tool is a collaborative and participatory process that takes a solution-oriented approach to achieve food sovereignty.10, 11 It does this by exploring the types of foods consumed, where it is sourced from, individual and tribal economies, and how food resources are managed. Although the Food Sovereignty Assessment Tool is used in intervention projects, it has not been used in research literature. This may be problematic as it is developed and implemented by First Nations people and hence would be an appropriate assessment tool to gather data on Indigenous food sovereignty. Community-based participatory research, as a research approach, emphasises the importance of creating partnerships between researchers and the people for whom the research is ultimately meant to be of use.10 The approach aims to help researchers bring focus to the peoples' perspectives, values and priorities.12, 13 This is a key approach to understanding and assessing Indigenous food sovereignty.

This review investigates existing literature on Indigenous food sovereignty assessment and adds to preliminary Indigenous food sovereignty research literature. Thus, the primary aim of this review is to identify and summarise existing Indigenous food sovereignty assessment approaches. The secondary aim is to explore Indigenous research methodologies used within the extracted studies. This review may guide future researchers to assess Indigenous food sovereignty and explore whether the approaches are effective in examining food environments to inform change and strengthen Indigenous food systems.

2 METHODS

With the team consisting of two Australian Indigenous researchers and five members of non-Australian Indigenous backgrounds, this review has attempted to work towards negating the usual western research practices and use a respective tone throughout to instil practice of cultural safety. This was guided by the two Australian Indigenous researchers. We acknowledge that this research team also consists of non-Australian Indigenous researchers of differing cultural backgrounds who may have a lens of pre-existing cultural bias. These researchers recognise their roles as outsiders looking into the diverse cultures and customs of Indigenous populations.14

The research team recognise this review did not originate from Indigenous communities and acknowledge that future Indigenous food sovereignty research should come from, and be guided by, Indigenous communities. This is essential in practising cultural safety and honouring First Nations peoples' sovereignty over their intellectual property in research and literature.15

The research protocol was not eligible for registration with International prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO) as it was considered a systematic scoping review and was instead uploaded to Open Science Framework (OSF) Home on 6 January 2022. The OSF is a tool that promotes open, centralised workflows by enabling capturing of different aspects of the research cycle, including developing a research idea, designing a study, storing, and analysing collected data, and writing and publishing papers. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist was applied.14 The search strategy was developed in PubMed and translated by the Systematic Review Accelerator Polyglot.15 A systematic search of four databases (Medline, Embase, CINAHL and Psycinfo) was undertaken in November 2021 by three authors, assisted by a librarian in developing the search strategy. The search terms utilised are outlined in Table S1. Forward and backward citation was conducted by three authors on all studies included for analysis.

The inclusion criteria are outlined in Table 1. Studies published from 1996 were included as the current definition of food sovereignty appeared in literature in that year. Intervention is defined as, ‘an act performed for, with or on behalf of a person or population whose purpose is to assess, improve, maintain, promote or modify health, functioning or health conditions’.16

| Inclusion criteria |

|---|

| Indigenous populations worldwide |

| Indigenous food sovereignty intervention studies in any language |

| Used one or more of the domains of Indigenous food sovereignty (community ownership, inclusion/promotion of cultural foods, inclusion of traditional food knowledge and environmental/intervention sustainability) or includes food and culture |

| Describes how Indigenous food sovereignty is assessed outside of the above domains |

| Studies published from 1996 to 2021 |

Systematic Review Accelerator Deduplicator was used to exclude duplicates of extracted studies.17 Studies were then uploaded to Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia) for further deduplication and screening.18 Titles and abstracts of the identified studies were screened independently in duplicates by three authors before progressing to full-text screening in the same format. A third author was nominated to resolve any conflicts in the screening process. One study was translated from Spanish to English via Google Translate and reviewed for accuracy by a native Spanish speaker. The process of consensus decision making by agreement rather than majority vote with all researchers led to the final selection of articles for the review.

The Mixed Method Appraisal Tool was utilised to assess the quality of studies by assessing the robustness of qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies.19 This was completed independently in duplicates by three authors (MA, AI, CL) with disagreements resolved by the third author. Studies assessed using the Mixed Method Appraisal Tool were then categorised as low, unclear, or high quality. Twelve percent of the extracted studies were selectively appraised by two experienced researchers.

A data extraction Excel (Microsoft) spreadsheet was developed based on the research question and reviewed by three authors. Data extraction was performed independently and cross-checked in thirds by three authors. Synthesis was categorised as follows, guided by a study by Maudrie et al (2021): (1) first author/year, (2) population/country, (3) study design, (4) community-based participatory research approach, (5) Indigenous food sovereignty assessment methods, (6) Indigenous food sovereignty frameworks and tools, (7) Indigenous food sovereignty domains (community ownership, inclusion of traditional food knowledge, inclusion/promotion of cultural foods and environmental/intervention sustainability) (8) data analysis, for the description of assessment in Indigenous food sovereignty. Two categories (9) acknowledgement of data sovereignty and (10) acknowledgement of Indigenous authors was included to assess use of Indigenous research methodologies and were crosschecked by one Indigenous researcher (KM). The four Indigenous food sovereignty domains were identified from a recent scoping review and captured the elements of Indigenous food sovereignty.7 As the included studies assessed Indigenous food sovereignty differently, their methods of assessment were collated and described narratively to allow for a deeper analysis of the methods.

3 RESULTS

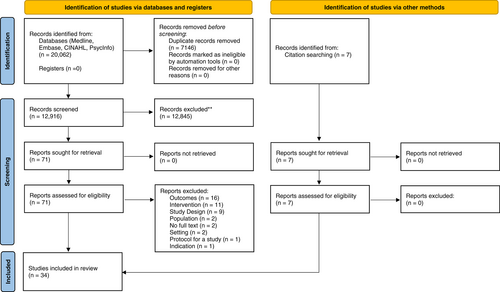

Database searching produced 20 062 records. After deduplication, 12 916 studies were screened against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Seven additional studies were identified through forward and backward searching.20-26 Following full text screening, a total of 34 studies were included in the study (Figure 1).

Characteristics of included studies are summarised in Table 2. Indigenous food sovereignty was assessed mostly in Canada (n = 13),12, 20, 22, 27-36 followed by United States of America (n = 8),23, 26, 37-42 India (n = 3),25, 43, 44 Ecuador (n = 3),24, 45, 46 Australia (n = 2),47, 48 and one study from Uganda,49, 50 South Africa,51 China,21 and Namibia respectively.52 Seven studies used validated frameworks, with the most frequent being the socio-ecological model (n = 3).22, 33, 38 The most frequent assessment method was interviews (n = 29),12, 21, 24-29, 32-34, 36-39, 45, 47-52 followed by focus groups and meetings (n = 23).12, 24, 27-31, 33-40, 46-48, 50-52 The most frequently used tool was the Traditional Food Frequency Questionnaire (n = 7),20, 29-31, 34, 35, 45 and Household Food Security Survey Model (n = 4),26, 28, 30, 31 which assessed inclusion of traditional and local food.

| First author/year | Population/country | Study design | CBPRa approach | Method | Frameworks | Tool | Indigenous food sovereignty domain/sb | Data analysis | Acknowledgments of data sovereignty | Acknowledgement of Indigenous authors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ban, 2020 | Kitasoo/Xai'xais British Columbia Canada |

Qualitative | Yes | Heritage database review Semi-structured interview |

– | – | Environmental/intervention Sustainability |

Conventional content analysis | X | X |

| Batal, 2021 (1) | 92 First Nations Communities—living on-reserve south of 60th parallel. Canada (n = 5176) |

Mixed methods | Yes | Questionnaire Interviews Food baskets |

– | USDA HFSSMc NNFBTd INACRIZe |

Inclusion of Traditional Food Knowledge | Thematic analysis Multivariate logistic regression analysis |

Data are owned by each participating community | X |

| Batal, 2021 (2) | 92 First Nations Communities—living on-reserve south of 60th parallel. Canada |

Mixed methods | Yes | Interview Questionnaire |

Ecosystem framework | TFFQf | Inclusion of Traditional Food Knowledge | Conventional content analysis Multivariable regression analysis |

Principles of OCAPg were followed. | X |

| Blanchet, 2021 | Syilx Okanagan First Nations Canada (n = 265 adults) |

Quantitative | Yes | Survey | Decolonizing health promotion framework | Adapted USDA HFSSMc, CCHSh, RHSi TFFQf |

Inclusion of Traditional Food Knowledge Environmental/intervention Sustainability |

Bivariate regression analysis | Principles of OCAPg were followed. | Two authors are members of the Syilx Nation. |

| Brimblecombe, 2015 | 4 remote Aboriginal communities (North coast, inland from North coast and Central desert) Australia |

Qualitative | Yes | Interviews Meetings Drawings Photovoice |

– | Developed Good Food Planning Tool | Environmental/intervention Sustainability |

Conventional content analysis | X | X |

| Brown, 2020 | The Northern Plains American Indian reservation community United states |

Qualitative | Yes | Interviews Meetings |

SEMj | – | Community Ownership Environmental/intervention Sustainability |

Inductive content analysis Coding based on SEMj |

X | X |

| Budowle, 2019 | Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho families in the Wind River Reservation, Wyoming United states |

Qualitative | Yes | Interviews Observations Talking/knowledge circles Storytelling |

Social ecological and community resilience frameworks | – | Community Ownership Inclusion and Promotion of Cultural Foods |

Grounded theory—deductive and inductive approach | X | One Indigenous author |

| Byker, 2020 | Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Indian Reservation, rural Montana United states |

Mixed methods | Yes | Survey Interviews |

– | USDA's Six-Item Short Form Food Security Survey Module | Environmental/intervention Sustainability | Thematic analysis Descriptive statistics |

X | Two authors include tribal members |

| Deaconu, 2021 | Ecuadorian highlands Ecuador (n = 91F) |

Mixed methods | Not mentioned | Survey Interview Focus groups |

– | TFFQf | Inclusion of Traditional Food Knowledge | Result triangulation Bivariate analyses |

X | X |

| DeBruyn, 2020 | 11–17 American Indians/Alaska Native communities United states |

Mixed methods | Yes | Observations | – | Shared data elements tool | Inclusion of Traditional Food Knowledge | Thematic analysis Descriptive analyses |

X | X |

| Domingo, 2021 | Williams Treaties Nations in Southern Ontario Canada |

Qualitative | Yes | Interviews Storytelling |

– | – | Environmental/intervention Sustainability | Thematic analysis | Principles of OCAPg were followed. | Co-investigator from an Indigenous service |

| Gallegos-Riofrío, 2021 | 144 individuals from 57 smallholder families from Caliata, Ecuador | Mixed methods | Yes | Surveys Site visits Workshops |

– | Lulun project survey adapted from Mexican National Health and Nutrition Survey | Environmental/intervention Sustainability | Results triangulation Member checking Conventional content analysis Descriptive analysis |

X | X |

| Ghosh-Jerath, 2021 | Munda Tribal Community, Khunti District of Jharkhand India |

Mixed methods | Yes | Surveys Focus groups |

– | – | Inclusion of Traditional Food Knowledge | Thematic analysis—deductive | X | X |

| Ghosh-Jerath, 2020 | 18 villages of Sunderpahari and Boarijor India |

Mixed methods | Yes | Focus groups Village transect walk |

– | Agricultural diversity tool Markey survey tool |

Inclusion and Promotion of Cultural Foods Inclusion of Traditional Food Knowledge |

Thematic analysis Categorisation of food items |

X | X |

| Hanemaayer, 2020 | Female Youth of Haudenosaunee community in southern Ontario Canada (n = 5F) |

Qualitative | Yes | Interviews Photovoice |

– | – | Inclusion of Traditional Food Knowledge | Thematic analysis | X | X |

| Heim, 2019 | Indigenous Namibian San community South Africa |

Mixed methods | Not mentioned | Unstructured interviews Observation |

– | – | Inclusion of Traditional Food Knowledge | Individual dietary diversity scoring of dietary recall data Calculated average rank of community food inventory data Author's assessment of food environment (availability, diversity, affordability, desirability and convenience) |

X | X |

| Ju et al., 2013 | 29 villages, Deqin, Shangri-la, Weixi villages Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, northwest Yunnan Tibet, China | Mixed methods | Yes | Surveys Questionnaire Interviews Observations Focus groups |

– | – | Environmental/intervention Sustainability | Not stated | X | X |

| Laberge et al., 2015 | 18–90 years old Mistrissini residents, Cree community of Mistissini in Northern Quebec Canada | Qualitative | Not mentioned | Focus groups | SEMj | – | Inclusion of Traditional Food Knowledge | Deductive-inductive thematic analysis—using Ecological model framework | X | X |

| Laberge et al., 2014 | 3 Aboriginal Cree communities (Mistissini, Eastmain, Wemindgi) (n = 374) in northern Quebec Canada |

Mixed methods | Used the approach but did not identify | Surveys Questionnaires Focus groups |

– | TFFQf | Inclusion of Traditional Food Knowledge | Thematic analysis—Ecological model Multivariate logistic regression analysis |

X | X |

| López-Ríos et al., 2021 | 46 families in the three Wayuu communities (Limunaka, Taiguaicat, Panarrer) Uganda (n = 204) |

Qualitative | Yes | Observations Knowledge circles Tours of territory Community forum Photovoice Semi-structured interview |

– | – | Inclusion and Promotion of Cultural Foods Inclusion of Traditional Food Knowledge Environmental/intervention Sustainability |

Content analysis | X | X |

| Marushka et al., 2021 | First Nation people living on reserves south of the 60th parallel Canada (n = 6487) |

Mixed methods | Yes | Survey Questionnaires |

– | USDA HFSSM TFFQ |

Inclusion of Traditional Food Knowledge Environmental/intervention Sustainability |

Descriptive statistical analysis | X | X |

| Natasha et al., 2018 | 31 males and females' key informants from 6 Villages of Vhavenda tribe in South Africa. | Mixed methods | Not mentioned | Interviews Surveys |

– | – | Inclusion and Promotion of Cultural Foods Inclusion of Traditional Food Knowledge |

Used Value Index and Relative Frequency index. Descriptive statistical analysis. |

X | X |

| Natcher et al., 2002 | First Nation people of the Little Red River Cree Nation of Alberta Canada |

Qualitative | Yes | Surveys Interviews Focus groups Site visits |

– | – | Community Ownership Environmental/intervention Sustainability |

Not stated | X | X |

| Neufeld et al., 2020 | First Nation elder women (n = 18) living on- and off-reserve in southwestern Ontario Canada |

Qualitative | Yes | Surveys Interviews |

SEMj | Developed Food Choice Survey | Inclusion and Promotion of Cultural Foods | Thematic analysis Member checking |

Principles of OCAPg were followed. | X |

| Noreen et al., 2018 | Adults (Eeyouch) from the Eeyou Istchee (Cree) of northern Quebec Canada (n = 330 M, 465F) |

Mixed methods | Not mentioned | Questionnaires Interviews |

– | TFFQ | Inclusion of Traditional Food Knowledge | Statistical analysis | X | X |

| Nu et al., 2017 | Yup'ik community located in a region of southwestern Alaska United states |

Qualitative | Yes | Focus groups | Developed own framework through focus group discussions—Fish-to-school conceptual model | – | Community Ownership Environmental/intervention Sustainability |

Thematic analysis | X | X |

| Penafiel et al., 2016 | Indigenous people of the rural parish of Guasaganda, in the highlands of Cotopaxi central Ecuador (n = 75) children, adolescents, adults, elders | Qualitative | Not mentioned | Interviews | Health Belief Model | – | Inclusion of Traditional Food Knowledge | Conventional content analysis | X | X |

| Richmond et al., 2020 | Reserve-based Indigenous peoples in southwestern Ontario Canada (n = 130 urban, n = 99, reserve base) | Mixed methods | Yes | Surveys Questionnaires |

– | Questions developed by the community TFFQf |

Inclusion of Traditional Food Knowledge | Descriptive statistical analysis | X | X |

| Rogers et al., 2018 | Indigenous and non-Indigenous participants from four remote Indigenous communities in Queensland and Northern Territories, Australia (Indigenous n = 23, and non-Indigenous n = 38) |

Qualitative | Yes | Interviews | – | Questions developed by community | Inclusion and Promotion of Cultural Foods Inclusion of Traditional Food Knowledge |

Thematic analysis | X | X |

| Schure et al., 2013 | Tribal members of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservations (CTUIR), Oregon United states (n = 27) |

Qualitative | Yes | Focus groups | – | – | Inclusion of Traditional Food Knowledge Environmental/intervention Sustainability |

Thematic analysis | X | X |

| Singh, et al., 2007 | Monpa women of West Kameng district, Arunachal Pradesh India (n = 120F, n = 40M) | Qualitative | Yes | Interviews Focus groups Observations |

– | – | Inclusion and Promotion of Cultural Foods Inclusion of Traditional Food Knowledge |

Not stated | X | X |

| Sowerwine et al., 2019 | Three Tribes in the Klamath River Basin of southern Oregon and northern California | Mixed method | Yes | Surveys Interviews Focus groups |

– | USDA HFSSMc | Community Ownership Inclusion and Promotion of Cultural Foods Environmental/intervention Sustainability |

Content analysis Statistical analysis |

X | X |

| Walch et al., 2021 | Elders in 12 rural, remote Alaska Native communities in the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta region in southwest Alaska, United States (n = 12) |

Qualitative | Not mentioned | Focus groups | – | – | Inclusion and Promotion of Cultural Foods Inclusion of Traditional Food Knowledge |

Thematic analysis | data collected belong to the Alaska Native People | X |

| Wendiro et al., 2019 | Artisanal mushroom producers across five districts Uganda |

Qualitative | Yes | Interviews Focus groups |

Innovation systems conceptual framework | – | Inclusion and Promotion of Cultural Foods Environmental/intervention Sustainability |

Thematic analysis | X | X |

- a CBPR—Community based participatory research.

- b Indigenous food sovereignty domains based on scoping review by Maudrie, 2021.

- c USDA HFSSM—The 18-item USDA Household Food Security Survey Module.

- d NNFBT—National Nutritious Food Basket Tool.

- e INACRIZ—Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada Remoteness Index Zone classification.

- f TFFQ—Traditional Food Frequency Questionnaire.

- g OCAP—The First Nations principles of ownership, control, access and possession.

- h CCHS—Canadian Community Health Survey.

- i RHS—Regional Health Survey.

- j SEM—Socio-ecologic model.

Half of the studies (n = 17) used a qualitative approach, followed by a mixed-method study design (n = 16), and only one study used a quantitative study design.30 Of all the studies included, 26 used a community-based participatory research approach. Studies that adopted a community-based participatory research approach assessed more Indigenous food sovereignty principals compared to studies that did not use the approach. Based on the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool, qualitative and quantitative studies were deemed high quality (Figure S1). The quality of mixed method studies was unclear as they did not report on whether there were divergences and inconsistencies within the results and whether they were adequately addressed.

All included studies assessed one or more of the four Indigenous food sovereignty domain principals, most studies assessed the inclusion of traditional food knowledge (n = 21), followed by environmental/intervention sustainability (n = 15), the inclusion and promotion of cultural foods (n = 10), and community ownership (n = 5). No studies assessed all four domains, however, one study assessed three of the four domains,50 and nine studies assessed two domains.23, 25, 26, 30, 32, 37, 41, 44, 49

Assessment methods varied with the most frequent method being interviews (n = 29), followed by focus groups and meetings (n = 23). Other common assessment methods included the use of surveys (n = 13), photovoice (n = 10), dietary assessments (n = 7), observations (n = 5), talking and knowledge circles (n = 5), storytelling (n = 3), and questionnaires (n = 2). Ten other assessment methods were used once throughout the included studies. Most studies (n = 26) used multiple assessment methods (Table 2).

In terms of the assessment of the four domains, the inclusion of traditional food knowledge was mostly assessed using interviews, focus groups and meetings. Environmental sustainability was mostly assessed using surveys, focus groups and meetings. Inclusion/promotion of cultural food knowledge and community ownership was mostly assessed using interviews, focus groups and meetings (Figure S2).

Twenty assessment tools were identified across half of the studies (n = 17). Nine studies used adapted tools, seven of these adapted the food frequency questionnaire to a traditional food frequency questionnaire,20, 29-31, 34, 35, 45 one study adapted the US Department of Agriculture Household Food Security Survey Model for the Indigenous populations of Canada,30 and one study adapted a survey from the Mexican National Health and Nutrition Survey. Four studies developed their own tools, two studies had their questions developed by the Indigenous community to use for their interviews and surveys,35, 48 one study used questions developed by Indigenous community members, and questions from the Canadian Community Health Survey and the Regional Health Survey.30 One study used a tool developed from a previous study.33 Four studies used established tools, three of the four used the US Department of Agriculture Household Food Security Survey Model.26, 28, 31 Batel et al., also used the National Nutritious Food Basket Tool,28 Byker used the US Department of Agriculture—Six-item Short Form Food Security Survey Module.39 Two studies did not mention whether their tools were established, developed, or adapted.40, 43 The most frequently used tool was the Traditional Food Frequency Questionnaire (n = 7) and US Department of Agriculture Household Food Security Survey (n = 4) which assessed the inclusion of traditional and local food.

Nine studies (n = 9) used frameworks to guide their Indigenous food sovereignty assessment.22-24, 29, 30, 33, 37, 38, 49 One study developed their own framework (Fish-to-school conceptual model) through focus group discussions with the participants.23 One study adapted an established framework by combining the socio-ecological model with community resilience framework.38 Seven studies used validated frameworks with the most used being the socio-ecological model.22, 33, 37

This review also investigated the acknowledgement of data sovereignty and Indigenous authors in the included studies. Only a small number of studies acknowledged data sovereignty and/or collaborated with Indigenous researchers or authors. Six studies acknowledged data sovereignty,12, 28-30, 33, 42 with two studies utilising the First Nations principles of ownership, control, access and possession.12, 29, 30, 33 Four studies acknowledged the Indigenous background of authors or investigators in the publication.12, 30, 38, 39 Only two of the included studies acknowledged both aspects.12, 30

4 DISCUSSION

This study is the first to systematically identify Indigenous food sovereignty assessment approaches, utilising either one or a combination of core domains of community ownership, inclusion of traditional food knowledge, inclusion and promotion of cultural foods, and environmental/intervention sustainability. This review also describes Indigenous research methodologies when assessing Indigenous food sovereignty.

A key finding of the review was that community-based participatory research was identified as an Indigenous food sovereignty assessment approach in over three-quarters of the studies.53 When assessing Indigenous food sovereignty, community ownership was assessed either qualitatively or using mixed methods with community-based participatory research. Similarly, studies assessing inclusion and promotion of cultural foods domain mostly utilised qualitative with community-based participatory research methods. Interventions included generational knowledge passed down from Elders and other knowledge keepers, storytelling, and honouring Indigenous ways of planting, cultivating, harvesting, processing and preparing Indigenous foods. The community ownership and inclusion and promotion of cultural foods interventions align with community-based participatory research principles, with ideally the community involved in the initiation, development, implementation and sustainability efforts of an intervention.53, 54 Over 70% of studies included Indigenous community members in the data analysis process, in the format of member checking,46 holding focus groups to assess quantitative results or discuss results for further analysis and interpretation of data.25, 45 However, only one study in this review described the community being involved with the initiation or development of the interventions, forming a Community Advisory Board for the entirety of the study, including study design and data dissemination.39 This allowed the researchers to gain a deeper understanding of the local ecological knowledge and dietary priorities of the community.39 Listening to what the community wants should inform research design. Future Indigenous food sovereignty research should focus on involving the community from the initiation and development of an intervention.

Inclusion of traditional food knowledge and environmental/intervention sustainability domains were the most heterogeneously assessed, with nearly half of both these study interventions again utilising community-based participatory research approaches. Data collection on the inclusion of traditional food knowledge primarily utilised validated tools, such as food frequency questionnaires or food basket surveys to access information such as dietary habits and food security status.26, 28, 31, 39 Aligning with previous Indigenous food sovereignty research some studies described Indigenous people's ecological responsibility to grow and process foods in an environmentally responsible way,10 as well as the responsibility of the researchers to conduct research in a sustainable way.21, 31, 38, 47 Interestingly, none of the extracted studies used the Food Sovereignty Assessment Tool that authors identified in this review, first published in Australian grey literature in 2004.10 Further research is warranted to understand whether these tools are effective in assessing Indigenous food sovereignty worldwide, particularly the relevance of dietary surveys to gather data on Indigenous communities' food intake and food security. Only Indigenous food sovereignty assessment projects in Native American communities utilised similar approaches and acknowledged data sovereignty.9, 55

In Indigenous research, it is necessary to explain the term ‘data sovereignty’.56 Indigenous food sovereignty research methodologies entail that researchers should be led by the communities in the research process to honour their sovereignty. Findings from this review reflected that only six studies acknowledged data sovereignty and/or collaborated with Indigenous researchers or authors, all of which were Canadian studies. Of these six studies, four utilised a data sovereignty strategy named the First Nations principles of ownership, control, access and possession, which shares similar principles with data sovereignty.55 Worldwide, Indigenous food sovereignty assessment and the use of Indigenous methodology, is limited in the research literature, with this review identifying 34 peer-reviewed articles from only nine countries. This highlights that the identified Indigenous food sovereignty assessment approaches may not be representative of the global First Nations populations. Indigenous peoples have raised concern over them being the subject of research by non-Indigenous people, leading to the neglect in Indigenous peoples' ownership of intellectual and cultural property generated from research, and research not responding to the needs or priorities determined by the people.55 Perhaps a more standardised approach to Indigenous food sovereignty assessment is possible, if researchers embrace the central concepts of data sovereignty, community ownership, community-based participatory research, elements of storytelling, talking/knowledge circles, photovoice and decolonisation of the research process.

This review has described the most frequently utilised Indigenous food sovereignty data collection methods; however, they may not be the most culturally appropriate methods.56 As discussed, some researchers have aligned with Indigenous methodologies by using a more Indigenous approach to inquiry, such as incorporating elements of storytelling, talking/knowledge circles and photovoice.31, 37, 39, 48, 51 These methods are reported as ways to better capture the communities' reality and decolonise the research process.31, 51 Grey literature also demonstrates that photovoice, symbol-based reflection, circles and storytelling are more methodologically rigorous and culturally appropriate for gathering data with Indigenous peoples.56 So, not only should future Indigenous food sovereignty research engage with Indigenous communities prior to study design, researchers also need to consider culturally appropriate methods.

A strength of this research is the comprehensive search strategy capturing relevant studies, with no universal definition of Indigenous food sovereignty. The four principal domains of Indigenous food sovereignty were utilised to ensure interventions that did not clearly articulate assessing Indigenous food sovereignty were included.7 Central to this review study design, was collaboration and leadership by First Nations researchers, supporting cultural safety and rigour.54 The researchers embraced, incorporated and supported Indigenous research methods, which is a key component of Indigenous epistemologies.55 Limitations of the review include that the concept did not originate from Indigenous communities, Indigenous food sovereignty is not well defined in literature, and the terminology First Nations or Indigenous for each study has not been verified. Although this review extracted a range of studies from the databases, scoping of alternate databases and sources were not completed. Including grey literature and Google Scholar may provide further studies and information not captured.7

In the process of the review, researchers have discovered an Indigenous quality assessment tool which may be beneficial for future research in this topic, as it supports cultural safety in research.52 Future research can expand the scope of investigation to grey literature of other countries with Indigenous populations. The Food Sovereignty Assessment Tool may be useful to utilise in future Indigenous led research projects.10 Further Indigenous food sovereignty assessment research is recommended, only if Indigenous communities voice their desire for this type of research, to strengthen the available literature and identify the effectiveness of methods assessing Indigenous food sovereignty.

This review used methods of decolonising research throughout the process and features elements of data sovereignty. It addresses the gap in the literature on assessing Indigenous food sovereignty and highlights the variety of methods and tools used across different countries with Indigenous Peoples. Further research could be warranted in identifying the strengths and weaknesses of the identified methods and tools in the assessment of Indigenous food sovereignty. Future research in Indigenous food sovereignty should arise from Indigenous communities to uphold data sovereignty and their voices in research.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

MA, AI, CL: Search design, search execution, screening of studies, quality assessment, citation checking, data extraction, data synthesis, drafting manuscript. BB, KM, KMS, LvH: Protocol development, critical review of the manuscript. The authors acknowledge Melissa Stannard for the Indigenous artwork developed in this review. Sarah Bateup, Faculty Librarian for the search strategy and database search. Sherry Tang, APD and PhD candidate, for providing template for quality bias assessment template and peer review of critical appraisals. Frances Mole, MNutrDietPrac, for translation of one study from Spanish to English.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.