Generational Renewal and Farm Succession: Insights from Ireland

Renouvellement générationnel et succession agricole : perspectives en Irlande

Generationswechsel und Hofnachfolge: Erkenntnisse aus Irland

Summary

enWe use Teagasc National Farm Survey (NFS) data to establish a better understanding about the age profile of people engaged in farming in Ireland and the related issue of farm succession. Insights are drawn from related research on the potential for farm partnerships to assist in improving generational renewal. The findings from the Teagasc NFS indicate a more complex relationship between economic performance and farm succession than is typically portrayed in the economic literature. The results indicate that in the non-dairy cattle system, the proportion of farm operators with an identified successor is lower for viable farms relative to non-viable farms and lower relative to viable farms in other farming systems. Cluster analysis of a sample of dairy farms indicates that the presence of young people in the household is just as important as farm economic viability in determining whether or not a farm successor is identified. The Teagasc NFS analysis indicates that many farms have young people contributing in terms of labour but delayed succession means fewer young farmers taking the role of farm manager. There is scope to increase the use of Farm Partnerships as pathways for younger farmers to progress from contributing labour on the farm to taking on a management role in the farm.

Abstract

frNous employons les données de l'enquête nationale sur les exploitations (National Farm Survey, NFS) de Teagasc pour mieux comprendre le profil d'âge des personnes engagées dans l'agriculture en Irlande et la question connexe de la succession agricole. Des enseignements sont tirés de recherches connexes sur le potentiel des partenariats agricoles pour contribuer à améliorer le renouvellement générationnel. Les résultats de l'enquête NFS de Teagasc indiquent une relation plus complexe entre la performance économique et la succession agricole que ce qui est généralement décrit dans la bibliographie économique. Les résultats indiquent que dans le système de bovins non laitiers, la proportion d'exploitants agricoles ayant un successeur identifié est plus faible pour les fermes viables que pour les fermes non viables et plus faible que pour les fermes viables dans d'autres systèmes agricoles. L'analyse groupée d'un échantillon de fermes laitières indique que la présence de personnes jeunes dans le ménage est tout aussi importante que la viabilité économique de l'exploitation agricole pour déterminer si un successeur agricole est identifié ou non. L'analyse des résultats de l'enquête indique que de nombreuses exploitations agricoles comptent des personnes jeunes qui contribuent en termes de main-d'œuvre, mais qu'une succession tardive signifie que moins de jeunes agriculteurs assument le rôle de chef d'exploitation. Il est possible d'accroître l'utilisation des partenariats agricoles pour permettre aux jeunes agriculteurs de passer du statut de contributeur à la ferme à celui de gestionnaire.

Abstract

deWir verwenden die Daten der nationalen Betriebserhebung des Teagasc (National Farm Survey - NFS), um ein besseres Verständnis über die Altersstruktur der in der irischen Landwirtschaft tätigen Personen und des damit verbundenen Themas der Hofnachfolge zu gewinnen. Dabei werden die Ergebnisse aus ähnlichen Forschungsarbeiten herangezogen, um das Potenzial von Kooperationen in der Landwirtschaft zur Verbesserung des Generationswechsels zu analysieren. Aus den Daten des NFS kann auf eine komplexere Beziehung zwischen wirtschaftlicher Leistung und Hofnachfolge geschlossen werden, als sie in der Literatur üblicherweise dargestellt wird. Die Ergebnisse deuten darauf hin, dass in der Rinderhaltung (außer Milchviehhaltung) der Anteil der Betriebsinhaberinnen und -inhaber mit einer geklärten Hofnachfolge bei wirtschaftlich rentablen Betrieben geringer ist als bei den nicht rentablen Betrieben– und auch geringer ist als im Vergleich zu rentablen Betrieben in anderen Betriebsformen. Mithilfe einer Clusteranalyse für eine Stichprobe von Milchviehbetrieben zeigen wir, dass junge Menschen im Haushalt ebenso wichtig sind wie die wirtschaftliche Rentabilität des Betriebs, wenn es darum geht, ob ein Betriebsnachfolger gefunden wird oder nicht. Die NFS-Betriebserhebung zeigt, dass viele Betriebe junge Menschen als Arbeitskräfte beschäftigen. Allerdings bedeutet eine hinausgezögerte Hofnachfolge, dass weniger junge Landwirtinnen und Landwirte die Führungsrolle des Betriebs übernehmen. Durch verstärkte Kooperationen könnte jungen Landwirtinnen und Landwirten der Weg von der Mitarbeit zur Übernahme einer Führungsrolle im Betrieb erleichtert werden.

Introduction

Within the EU and in many other parts of the world, an ageing farmer population is evident and poses a major challenge if farms are to remain viable. This can to some extent be linked to health improvements and rising life expectancy. However, this ageing cohort is mainly a consequence of limited opportunities for younger successors or new entrants entering the farming profession.

Coopmans et al. (2020) conclude that it is more appropriate to define the generational renewal challenge at the national or regional level due to the varying trends in the age distribution of farmers in different EU Member States. We therefore focus on the generational renewal challenge in Ireland. In 2020, almost 33 per cent of farm holders in Ireland were aged 65 years and over, an increase from 23 per cent in 1991. The proportion of farm holders aged less than 35 years decreased from 13 per cent in 1991 to just 7 per cent in 2020 (CSO, 2021).

The extent of ageing in the farmer population in Ireland requires serious consideration given the important role of agriculture in rural economies. Agriculture has important multiplier effects and supports employment in towns and villages throughout Ireland. A decline in the number of young people and new entrants entering the profession reduces the potential economic contribution of agriculture to rural economies. O'Rourke (2019) highlights the risk of reduced population and land neglect or abandonment. This risk is particularly acute in regions where the direct economic returns from agriculture are low and where there is geographical isolation alongside poor infrastructure and services.

In terms of the positive contribution of young farmers, much recent research points to the environmental awareness of younger farmers across Europe. Pérez et al. (2020) conclude that younger farm owners possess a greater awareness of agriculture-related environmental issues, are faster to adopt new eco-compatible technologies and adapt more easily to changes in agriculture and rural policy. A continuation in the ageing of the farmer population may therefore hinder the efforts of the overall sector in improving environmental sustainability.

Sutherland (2023) concludes that there is very little evidence internationally of a shortage of young people interested in farming and that the low rate of entry into the profession can be attributed to barriers including low incomes and difficulties in accessing land and finance.

In Ireland, the expansion of the dairy farm sector has provided opportunities for young people with an interest in the farming occupation. Deming et al. (2020) report some optimism among those undertaking education as dairy farm managers with indications that this education is helping participants to manoeuvre around the constraints of non-inheritance. In terms of direct financial support, payments for young farmers (under 40 years old) are available to qualified applicants for a 5 year-period up to €175 per hectare for a maximum of 50 hectares.

The scale of the generational renewal challenge is often assessed using data in relation to farm holder demographics. However, the assessment of this challenge requires data in relation to farm succession as this is by far the most common way for people to enter farming as a profession (Sutherland, 2023).

In this article, we have three broad objectives relating to the scale of the generational renewal challenge in Ireland. The first objective is to explore whether or not farm successors are identified, the variation by farm system and whether or not succession identification is stronger for viable farms relative to non-viable farms.

The second objective is to gather more information about the age profile of the farmer population. We ask the question whether or not an alternative family farm age index, as proposed in Burton (2006), could be of added value. Burton first proposed this type of index in response, to among other things, the rise in farm size and the emergence of more complex management/operating systems relative to those under the control of a ‘principal decision-maker’. The approach remains quite novel as only a few studies have adopted similar approaches (for example, Yanore et al., 2024). In addition to the age index, we describe the proportion of farms with a young family member contributing labour.

The third objective is related to farm succession. We question the association between succession intentions and social factors including isolation and excessive workload. Using cluster analysis, we compare specialist dairy farms in terms of farm successor identification according to some economic and social dimensions. Our analysis provides many intuitive findings but also some unexpected findings in relation to the association between farm succession intentions and profitability. The farm profitability is often considered vital towards increasing the likelihood of farm succession (Pitson et al., 2020). Our research points to a more nuanced story with social factors appearing to be just as important in influencing successor identification.

Summary of research approach

This analysis uses data from the Teagasc National Farm Survey (NFS) which operates as part of the EU Farm Accountancy Data Network (FADN). A random, nationally representative sample of farms is selected annually in conjunction with the Central Statistics Office (CSO). In the Teagasc NFS dataset, each farm is assigned a weighting factor so that the results of the survey are representative of the national population of farms. A range of socio-demographic data relating to the farmer and farm household is collected annually. The data used for this research are based on the 2018 and 2021 Teagasc NFS surveys. Additional data pertaining to farm succession were collected in 2018 and contribute to our analysis.

There are essentially two stages to the empirical analysis with the 2018 data. The first stage of the analysis is based on successor identification and the subset of the sample containing farms with an operator aged 50 years or older (542 farms). The analysis is focused on farm operators in this age group because the proportion with an identified successor is much lower for younger farm operators.

The second stage is based on cluster-analysis techniques and the sample of dairy farms. We compare three clusters in terms of the proportion of farm operators identifying a chosen successor and in terms of the income per labour unit. A sample of 177 dairy farmers (aged 50 years and older) is included in the cluster analysis with some additional analysis about 124 younger dairy farmers (aged under 50 years old). The cluster analysis is focused on dairy farms, which provides a more homogeneous group of farms than would emerge from an analysis of the entire sample of farms. The economic viability of farms differs strongly between farming systems in Ireland and it seems best to focus on one system. The research throws light on the farm succession challenges for a system, which tends to involve full-time rather than part-time farming and where there is a relatively high economic viability in recent times.

In addition, we explore a method to overcome the over-emphasis of the available statistics on the age of the principal decision-maker. This approach drawing on Burton (2006) involves the calculation of an age index based on the age of each family member who is working on the farm and the number of hours worked by each of these family members. Family labour input is included in the Teagasc NFS, with a self-reported estimate of the number of hours worked on-farm per annum provided for each family member. We use data from the 2021 Teagasc NFS on self-reported family labour hours to construct a farm family age index for each farm (sample of 828 farms representing 84,100 farms nationally).

Farm successor identification

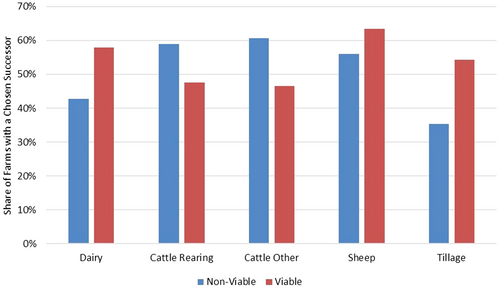

Our research findings point to a nuanced story about farm succession in Ireland. Figure 1 indicates that for dairy, sheep and tillage farming systems, the proportion of farm holdings with an identified successor is higher for viable relative to non-viable holdings. This is particularly the case for tillage farming. However, this does not appear to be the case for non-dairy cattle farms. This is an important finding as this farming system accounts for about 55 per cent of all commercial farms in Ireland.

Share of farm holders with a chosen successor by farming system and farm viability status

Note: Only farm holders aged 50 years and older are included.Source: Authors’ calculations using Teagasc National Farm Survey 2018.

Economically viable cattle farms face challenges with generational renewal. This could be due to the greater labour intensity and management responsibility associated with operating more commercially focused cattle farms while the less viable extensive farms tend to be less demanding in terms of time requirements and therefore provide scope for participation in off-farm employment.

Relative to viable farms in other systems, viable cattle farms appear to have a relatively low proportion with an identified successor. To some extent, this may be influenced by the poor economic performance of cattle farming in 2018 in the aftermath of a fodder crisis and a decline in finished cattle prices. Sheep farms (viable and non-viable) appear to have a relatively high percentage with a chosen successor identified. Based on the 2010 and 2020 censuses of agriculture, there was a 28.6 per cent increase in the number of farms in the sheep farming system and a 4.6 per cent decline in the number of farms in specialist beef cattle production, which may indicate some movement between systems. The census results support our finding that succession intentions are relatively strong for sheep farms. However, more research is needed to understand the activity taking place on sheep farms undergoing succession and the reasons for the increasing participation in this system between 2010 and 2020 and the participation levels in more recent years.

Much emphasis tends to be placed on the importance of economic factors in influencing farm succession (for example, Pitson et al., 2020). However, the relationship between farm successor identification and farm economic performance can be quite weak in some farming systems. Other factors (including social and demographic) can determine the extent of successor identification. The non-pecuniary benefits of farming influence farm labour decisions (for example, Howley et al., 2014). Similarly, recent data collected on small farms in Ireland found that enjoyment of farm work and maintaining a good quality of life are primary motivators for operators (Teagasc, 2024).

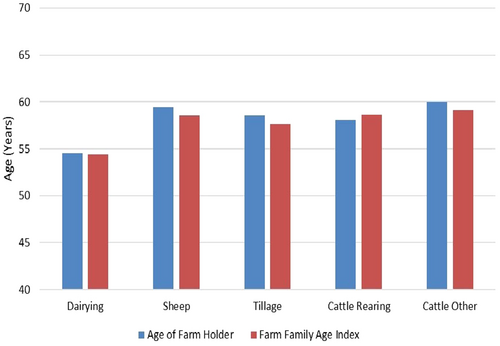

Family Farm Age Index

Most available statistics in relation to the age of the farming population appear insufficient in helping us to form conclusions about whether or not a generational renewal problem exists. This research confirms that the ageing of the farmer population is a real challenge even after taking into account the contribution of younger household members in terms of farm labour input. The family age index results are presented in Figure 2. In the case of sheep, tillage and cattle other farming systems, the use of a farm family age index appears to slightly improve the age profile of farms. However, the age profile of cattle rearing farms increases when one accounts for the input of all family labour. The choice of indicator makes very little difference for specialist dairy farms. The conclusions from this analysis are somewhat different to those of Burton (2006), who originally proposed this type of approach. Burton identified much greater differences between the average value of the age index and the average age of the farm operator. This may be due to the different context with Burton's analysis concerned with typically much larger farms.

Average age statistics by farming system

Note: Farm Family Age Index weights based on reported labour hours and age of household members working on the farm.Source: Authors’ calculations using Teagasc National Farm Survey 2021.

Figure 3 details the proportion of farms with a young person (aged 40 years or less) providing labour on farms. This indicates that one-third of specialist dairy farms have a young person providing at least 200 hours of labour per annum. The comparative figure is 27 per cent for sheep farms and is slightly lower for tillage and cattle systems. The relatively high incidence on sheep farms is likely influenced by the seasonality of labour demand on those farms at lambing time.

Proportion of farms with a family member (aged 40 years and under) providing labour by farming system

Note: Farm household member must be 40 years old or younger and providing a minimum of 200 hours of labour per annum.Source: Authors’ calculations using Teagasc National Farm Survey 2021.

Data on family labour input provides a more optimistic picture on the demographics of Irish farming than is apparent from solely focusing on the age of the farm operator. Despite this, the 2020 Census of Agriculture reported that only 13 per cent of farm holders in Ireland are aged below 40 years, highlighting the problem of delayed succession in terms of managerial control on Irish farms.

Cluster analysis

We investigate differences across dairy farm respondents using hierarchical cluster analysis. We focus on dairy farms as farm viability tends to be higher for the dairy farming system relative to the other main farming systems in Ireland. In addition, there is an advantage in choosing to analyse a relatively homogeneous group of farms as is the case with specialist dairy farms. The analysis enables us to highlight the potential importance of social factors in influencing successor identification.

The variables used to undertake the cluster analysis are the number of household members aged between 16 and 44 years, whether or not the farm is participating in an Agri-Environment Scheme (AES) and whether or not the farm is economically viable. The definition of the variable in relation to young people is due to the available data for the age of all household members. The methods and number of clusters were chosen based on established rules and methods described briefly in Latruffe et al. (2013).

We focus on the subset of farmers in the age category 50 years and older as the vast majority of farmers aged less than 50 years old have not reached the point of choosing a successor. This leads to three cluster groups of specialist dairy farms where the farm operator is aged 50 years or older. The cluster analysis is based on a different year as the data in relation to farm succession were specially collected for the 2018 Teagasc NFS survey and did not form part of the 2021 survey. In the 2018 Teagasc NFS survey, the farmers were asked a question in relation to the presence of stress related to their workload. 2018 was a particularly challenging year due to a summer drought, fodder shortages and a decline in cattle prices in the second half of the year and this motivated the inclusion of this question. Table 1 details the average family farm income per family labour unit and the proportion of farm operators with a chosen successor. In addition, we describe some statistics for farm operators less than 50 years of age.

| No. of Farms | Share with a Chosen Successor (%) | Average Farm Income per Labour Unit | Viability Rate (%) | Share in AES Scheme (%) | Average Number of Household Members Aged 16–44 years | Share Reporting Workload as a Source of Stress | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 69 | 66.9 | 56,224 | 100 | 0 | 1.73 | 49.6 |

| 2 | 48 | 43.6 | 57,717 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 57.2 |

| 3 | 60 | 53.0 | 19,814 | 21.6 | 40.1 | 0.96 | 53.3 |

- Notes: Cluster 1 – Viable Dairy Farm operated by older dairy farmer with young people in the household; Cluster 2 – Viable Dairy Farm operated by older dairy farmer with no young people in the household; Cluster 3 – Other Dairy Farm operated by older dairy farmer with young people in the household; AES Scheme – Only Cluster 3 has participation in an AES scheme.

- Source: Author's calculations using 2018 Teagasc National Farm Survey data.

Results from the cluster analysis indicate that there are varying drivers and barriers to farm succession, and these appear to be linked to particular economic, demographic and social characteristics. The share of farmers with a chosen successor in Cluster 1 is 67 per cent, which is the highest among the clusters. This cluster comprises 69 economically viable farms operated by a dairy farmer (50 years of age or older) with no participation in AES. This cluster has the highest number of people aged 16 to 44 years old in the household, further reflecting the importance of having younger people in the household for successor identification.

The lowest share of farmers with an identified successor is in cluster 2, which comprises 48 economically viable dairy farms. Farms in this cluster are not participating in an AES scheme and there are no members of the household aged between 16 and 44 years. Additionally, farms in this cluster have reported a relatively high workload stress and this may be linked to a lack of family support in sharing the workload.

Most dairy farms are categorised as viable according to the standard definition. Social factors such as farm-related stress or absence of younger family members seem to be just as important in the context of dairy farm succession. The third cluster consists of 60 dairy farms with particularly low farm income per labour unit in 2018 with just 21.8 per cent of farms being economically viable. Further analysis of the data indicates that farms in this cluster tend to have lower viability rates than other dairy farms in most years. However, viability rates in this cluster were particularly low in 2018 due to the challenging weather/production conditions. A relatively high proportion of these farms are participating in an AES scheme (40.1 per cent). Despite the low economic viability rate, these farms appear to be more likely to have an identified successor relative to the farms in cluster 2.

In terms of the farm operators less than 50 years old, these younger farmers have a relatively high income with the vast majority being economically viable (78.1 per cent). However, these farmers appear more likely to report a stress-related workload problem than the three clusters of older farmers. Partly due to the younger age of these farmers, only 14.1 per cent have reached the point of having a chosen successor.

Differences across these clusters confirms the fact that the succession decision is nuanced and driven by farm specific factors and characteristics pertaining to, for example, the economic viability of the operation and the demographic and social status with regard to household membership and workload management.

Farm partnerships

The above analysis points to some novel findings about the challenges in relation to generational renewal for agriculture in Ireland. In terms of the potential policy response, a number of opportunities appear to be available.

Opportunities include the formation of collaborative farming initiatives such as farm partnerships. Shin et al. (2023) highlights that there is ‘significant potential for growth in collaborative farming via alternative business structures’. Farm partnerships between older and younger farmers could be particularly helpful in addressing issues on larger farms, ensuring that knowledge is passed on to the next generation while maintaining the productivity and future viability of the farm.

Farm partnerships can reduce the workload of older farmers and support younger farmers to get involved in farm management, thereby enabling the next generation to take over the farm business in gradual steps. Registered Farm Partnerships (RFPs) are the most common type of formal farm partnership arrangement in Ireland. These partnerships are registered with the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine (DAFM) and provide farmers and successors with a structure for appropriate profit sharing over the duration of the partnership. The number of RFPs in Ireland has reached over 3,800 in 2024 (Fennell, 2024). This represents a seven-fold increase in a 10 year timeframe.

RFPs can avail of greater incentives for farm investment. The Targeted Agricultural Modernisation Scheme (TAMS III) offers higher grant rates for capital investment by young farmers with grant rates applying to larger investments in the case of farm partnerships (DAFM, 2024a). Succession Farm Partnerships (SFPs) were introduced in 2017 and are a particular form of RFP, involving a tax credit incentive to encourage farmers to transfer the farm business to their identified farming successor or successors. Under the SFP, a farmer agrees to transfer at least 80 per cent of the farm assets to a chosen successor within a specified period.

Farm partnerships also provide some non-financial benefits for less profitable farms, as they facilitate a staged exit of an older farmer and the entry of a young farmer. Farming is a way of life for many older farmers and considering retirement from daily routines and social circles in the farming community presents many difficulties including a perceived loss of social status and power (Conway et al., 2022) and perceived economic risks related to the control of farm assets and access to income (Leonard et al., 2020). Farm partnerships can address some of these problems by providing an alternative to retirement while still advancing the process of generational renewal.

Farm partnerships are increasing in number. Our research indicates that many farmers are interested in considering this form of collaborative arrangement. The vast majority of farm successors tend to be family members (CSO, 2022). Table 2 refers to the sample of farms in the 2018 Teagasc NFS survey where the farm holder is aged 50 years and older. This table shows that 19 per cent of these farmers expressed an interest in forming a partnership with their chosen successor before retiring from farming. The majority of these farm holders (68 per cent) did not express an interest in forming a partnership before retirement. Only 1 per cent of these farmers reported being already in a farm partnership while 12 per cent provided a ‘Don't know’ response. Overall, the interest expressed in a possible farm partnership is impressive.

| Proportion of Farm Holders (%) | |

|---|---|

| Yes | 19 |

| No | 68 |

| Don't Know | 12 |

| Already in a Partnership | 1 |

- Source: Authors’ calculations using 2018 Teagasc National Farm Survey data.

Research under the EU Ruralisation project (https://ruralization.eu/) points to the importance of formalised farm partnership arrangements given that joint herd number options are inclined to be informal with no commitment to the transfer of assets. In Ireland, a new Succession Planning Advice Grant scheme has been introduced to encourage older farmers into planning for the inter-generational transfer. This new grant supports farmers (aged 60 years and above) in receiving succession planning advice by contributing up to 50 per cent of vouched legal, accounting and advisory costs, subject to a maximum payment of €1,500 (DAFM, 2024b).

Recent evidence indicates that 44 per cent of Registered Farm Partnerships have at least one female member and this emphasises the importance of female farmers having equal power in the decision-making process.

Lessons and implications

Generational renewal is one of the ten key objectives of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) 2023–2027, which aims to ensure a vibrant and resilient agricultural sector for future generations. Amongst other things, this requires skilled and innovative young farmers who respond to societal demands for food quality and the provision of environmental public goods. The Irish CAP Strategic Plan aims to support generational renewal by providing complementary income support and implementing targeted measures that encourage young farmers to enter the agricultural sector, stabilise their income and sustain their businesses (DAFM, 2024c).

This research highlights the need for tailored interventions in support of generational renewal with a holistic approach that integrates economic, demographic and social dimensions. For instance, economically viable farms without young adults (Cluster 2) could benefit from targeted policy measures to support workload management, whereas less viable farms (Cluster 3) could benefit from financial assistance and support around succession planning.

Policies could be more effective if focusing not only on improving economic viability but also on addressing social and demographic challenges. One such strategy is increasing awareness of and facilitating the use of RFPs, which facilitate farm succession under a dual approach that prepares older farmers to hand over the business within the joint farm management period. This provides targeted initiatives to encourage young adults' involvement in the operation of the farm (and the necessary financial supports) as well as assisting in addressing any labour challenges encountered by established (older) farm operators. Such mechanisms can therefore provide ‘win-win’ solutions, incentivising farm succession and inter-generational transfer, taking account of both family dynamics and broader social factors. Farms with identified successors often have a younger generation involved, suggesting that engaging younger family members early on is beneficial. Further research is necessary to develop effective interventions. Continuous data collection on demographic and social factors relating to farm succession can help to refine suitable support programmes and policies.

Acknowledgement

Funding provided by the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine under the project entitled RENEW2050 - Rural Generational Renewal 2050 -2019R414. Open access funding provided by IReL.

Box 1: Definitions of key terms/concepts

Economic Viability: Family farm income is sufficient to cover family labour (remunerated at the agricultural wage rate) and provide a 5 per cent return on non-land assets.

Family Farm Age Index: This represents the age of the family members contributing labour to the farm weighted according to the number of self-reported labour hours.

Family Farm Income: Gross output less total net expenses; it represents the total return to the family labour, management and capital investment in the farm business.

Farm Succession: The transfer of managerial control from a farmer to their successor; this can take place over time, often over the lifetime of a successor.

Farm Inheritance: This refers to the legal transfer of assets to a successor, which generally takes place following succession.

Farmer Retirement: The final process affecting the overall farm transfer is that of retirement, while succession and inheritance relate more to a successor, retirement specifically impacts the outgoing farmer.

Generational Renewal: Generational renewal in a rural development context goes beyond a reduction in the average age of farmers in the EU. It is also about empowering a new generation of highly qualified young farmers to bring the full benefits of technology to support sustainable farming practices in Europe.

Further Reading

Farm partnerships can reduce the workload of older farmers and support younger farmers to get involved in farm management, thereby enabling the next generation to take over the farm business in gradual steps.

Les partenariats agricoles peuvent réduire la charge de travail des agriculteurs plus âgés et aider les plus jeunes à s'impliquer dans la gestion agricole, permettant ainsi à la prochaine génération de reprendre l'entreprise agricole par étapes progressives.

Kooperationen zwischen landwirtschaftlichen Betrieben können die Arbeitsbelastung älterer Landwirtschaft Betreibender verringern und jüngere Landwirtinnen und Landwirte dabei unterstützen, sich in die Betriebsführung einzubringen. Auf diese Weise kann die nächste Generation den landwirtschaftlichen Betrieb schrittweise übernehmen.