Avocado Production: Water Footprint and Socio-economic Implications

Production d'avocat : empreinte hydrique et implications socio-économiques

Avocadoproduktion: Wasser-Fußabdruck und sozio-ökonomische Auswirkungen

Summary

enThe market for avocados is among the fastest expanding markets worldwide, and consumption, particularly in North America and Europe, has increased during recent decades due largely to a combination of socio-economic and marketing factors. Avocado production, however, is associated with significant water conflicts, stresses and hot spots, as well as with other negative environmental and socio-economic impacts on local communities in the main production zones. In considering near-future climatic change in tropical and subtropical areas where avocados are produced, an urgent road map is needed to avoid and mitigate negative effects of avocado production. This road map needs to bring authorities and policymakers together with large and small producers from areas with present and projected future water scarcity to evaluate the critical capacity and optimal levels of avocado production. The EU as one of the most important markets for this fruit could facilitate and support such a road map and at the same time critically promote imports from countries and regions where current and future severe water risk are not further threatened. Finally, consumer behaviour can contribute to minimising negative effects by making a conscious effort to engage in ethical consumption and environmental conservation, contributing to the sustainability of communities in producing areas.

Abstract

frLe marché de l'avocat est l'un des marchés à la croissance la plus rapide au monde. En effet, la consommation a augmenté au cours des dernières décennies, en particulier en Amérique du Nord et en Europe, en grande partie en raison d'une combinaison de facteurs socio-économiques et de marketing. Or la production d'avocat est associée à d'importants conflits, stress et points chauds en termes d'utilisation de l'eau, ainsi qu’à d'autres impacts environnementaux et socio-économiques négatifs sur les communautés locales dans les principales zones de production. En considérant le changement climatique proche dans les zones tropicales et subtropicales où les avocats sont produits, une feuille de route urgente est nécessaire pour éviter et atténuer les effets négatifs de la production d'avocat. Cette feuille de route doit rassembler les autorités et les décideurs politiques ainsi que les petits et grands producteurs des régions marquées par une pénurie en eau qui se poursuivra selon les projections, afin d’évaluer la capacité critique et les niveaux optimaux de production d'avocat. Étant l'un des marchés les plus importants pour ce fruit, l'Union européenne pourrait faciliter et soutenir une telle feuille de route et en même temps promouvoir de manière critique les importations en provenance de pays et de régions où les risques hydriques graves actuels et futurs ne sont plus une menace. Enfin, le comportement des consommateurs peut contribuer à minimiser les effets négatifs en faisant un effort conscient pour s'engager dans une consommation éthique et la conservation de l'environnement, contribuant ainsi à la durabilité des communautés dans les zones de production.

Abstract

deDer Avocadomarkt gehört zu den am schnellsten wachsenden Märkten weltweit. Der Verbrauch, insbesondere in Nordamerika und Europa, hat in den letzten Jahrzehnten vor allem aufgrund einer Kombination aus sozioökonomischen und marketingbezogenen Faktoren zugenommen. Die Avocadoproduktion ist jedoch mit erheblichen Wasserkonflikten, Belastungen und Krisenherden verbunden sowie mit anderen negativen umweltbezogenen und sozioökonomischen Auswirkungen auf die lokale Bevölkerung in den Hauptanbaugebieten. Angesichts des bevorstehenden Klimawandels in den tropischen und subtropischen Anbaugebieten wird ein Aktionsplan dringend benötigt, um die negativen Auswirkungen der Avocadoproduktion zu vermeiden und abzuschwächen. Dieser Aktionsplan muss Behörden und politische Entscheidungstragende mit großen und kleinen Anbaubetrieben aus den Gebieten mit gegenwärtiger und prognostizierter Wasserknappheit zusammenbringen, um die kritische Größe und das optimale Niveau der Avocadoproduktion zu bewerten. Die EU als einer der wichtigsten Märkte für diese Frucht könnte einen solchen Aktionsplan ermöglichen und unterstützen. Gleichzeitig könnte sie Importe aus Ländern und Regionen fördern, in denen gegenwärtig und zukünftig keine Wasserrisiken befürchtet werden. Schließlich kann auch das Verhalten der Verbraucherinnen und Verbraucher dazu beitragen, die negativen Auswirkungen zu verringern. Dafür müssten sie sich bewusst um ethischen Konsum und Umweltschutz bemühen, um so zur Nachhaltigkeit der Gemeinden in den Anbaugebieten beizutragen.

Avocado consumption

In this article, we argue that the trend of increasing avocado consumption during recent decades is causing negative environmental and socio-economic impacts in many countries and that a road map to attain sustainability is urgently needed. Persea americana (avocado or agauacate, palta in Latin America) is a warm climate tree species whose fruit is used for direct consumption, as well as for production of diverse products including oil and cosmetics (Schaffer et al., 2013). Present estimates indicate that globally around 5 million tonnes (t) are consumed each year. The increasing popularity of avocados in recent years among countries in Europe, North America and the developed parts of Asia, is partially related to lifestyle trends and potential health benefits. However, the high annual avocado consumption, estimated to be on average 3.5 and 1.05 kg per capita in the USA and Europe (Netherlands: 2.28 kg), respectively (CBI, https://www.cbi.eu/) is also due to improved marketing methods across the globe (https://www.persistencemarketresearch.com/) and to other socio-economic changes. For example, the strength of Mexico as a producer within the avocado sector increased significantly after 1997 with the advent of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), when the price of imported avocados decreased (Carman, 2019). The increase in avocado popularity within the US has also been accompanied by a strong marketing campaign; for example, through a Superbowl commercial entitled ‘Avocados from Mexico’. With publicity and social media advocating avocado health benefits, consumption per capita in the US increased by 406 per cent between 1990/91 and 2016/17 (Carman, 2019). For comparison, consumption of all commercially produced fruits increased in the same period by only 28.5 per cent (Carman, 2019).

Similarly, in Europe, avocado consumption per capita increased on average by 179 per cent (ranging from 54 per cent in France to 248 per cent in Italy) between 2012/13 and 2017/18, with industry expectations of further increases (CBI: https://www.cbi.eu/). A significant portion of this demand is driven by the younger millennial generation in Europe and the rise of flexitarian diets, which emphasise more plant-based food. The global avocado market is anticipated to grow at a compound annual rate of 6.2 per cent during the period 2017–2027 (https://www.persistencemarketresearch.com/). Further, retail prices of avocados in the EU have remained relatively constant due to their relatively secure and steady supply (https://www.cbi.eu/). The main avocado importing countries in 2018 in descending order were: USA, Netherlands, France, Italy, UK and Spain (USDA: https://gain.fas.usda.gov/#/).

Avocado production

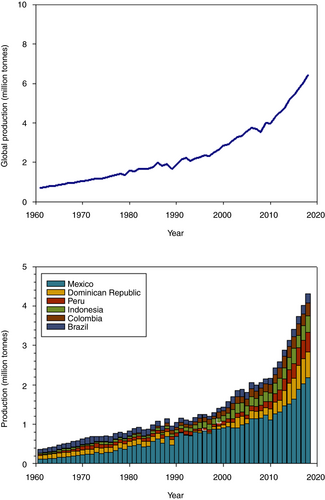

Analysis of avocado production data, which include official, estimated and unofficial values, reported by FAOSTAT in 2019 (http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC), shows that 66 countries currently produce over 25 t/year; and that between 1961 and 2018, this has grown by a total of around 5.7 million tonnes (Figure 1). This increase has been particularly strong since 1990 among the six largest producers in 2018 shown in Figure 1. In Europe, the main producer – and only exporting country – is Spain (89.6 kt in 2018), followed by France (2.5 kt) and Greece (1.6 kt). Given that this production is not enough to satisfy the European market demand, the EU imposes a tariff on imported avocados (as well as on other fruits) of 5.1 per cent in order to protect the fledgling European avocado industry (EU Market Access Database: https://madb.europa.eu/madb/).

Data source: FAOSTAT (http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC).

In North America, the main avocado supplier over the entire year is Mexico (where the fruit is native), while Europe is supplied by Peru, South Africa and Kenya in summer and by Chile, Mexico, Israel and Spain in winter. However, in April 2020, the EU signed an updated free trade agreement with Mexico, which will mean that Mexican avocados imported into the EU will be tariff-free (https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_756). By reducing trade friction and improving trade links, this agreement will increase the share of Mexican avocados being sold to the EU market.

Avocado water footprint

Production of avocado takes place in typically subtropical, tropical and Mediterranean climates where water consumption, in general, is high and where trees of this species cannot usually be grown at commercial scale without supplementary irrigation. Freshwater resources are increasingly over-exploited in many parts of the world with direct negative consequences for food production and humankind (Falkenmart, 2013). In a world where irrigated agriculture accounts for around 70 per cent of the water use worldwide (OECD, 2017), assessing potential imbalances between production and water use is essential to identify areas at risk around the world and to assure sustainability, as well as addressing social issues.

To assess the impact of avocado production on water resources, we first calculated the average green (rainwater) plus blue (surface and groundwater) water footprint of this fruit (Mekonnen and Hoekstra, 2010) for each of the producer countries. The database available for the period 1996–2005 shows that the world average green water footprint for avocado is 849 m3 t–1 (cubic metres of water consumption per tonne), ranging from 31 m3 t–1 in Saint Lucia in the Caribbean to 4,494 m3 t–1 in the region of Beja, Portugal where according to FAOSTAT recorded production took place only between 1990–1994. The blue water footprint on average is 237 m3 t–1, but ranges from 0 m3 t–1 in Grenada and some regions of Guatemala to 2,295 m3 t–1 in the region of Antofagasta, followed by Tarapacá (2,196 m3 t–1) in Chile. For comparison, the world average green and blue water footprint estimated for all fruits is 727 m3 t–1 and 147 m3 t–1, respectively (Mekonnen and Hoekstra, 2010). According to Mekonnen and Hoekstra, this average is higher for fruits than for vegetables (green: 194; and blue: 43 m3 t–1); but lower than for example, for cereals (green: 1,232 m3 t–1; and blue: 228 m3 t–1).

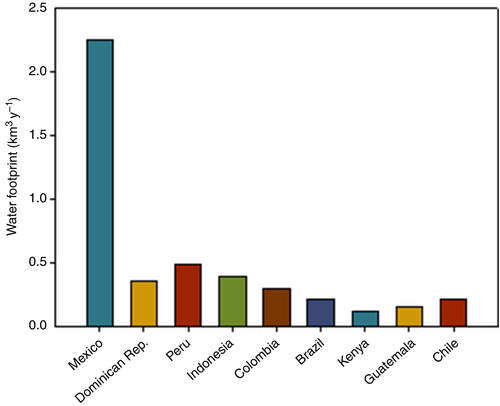

We then multiplied the average water footprint for each of the top avocado producer countries by their respective avocado production in 2018 (Figure 2). In some countries there are large differences in the water footprint among regions, for example, in countries extending over different climatic zones such as Chile. However, for the sake of simplicity and because for most countries detailed production per region is not available, we used the average for each country. Further, for this estimation, we also conservatively assumed that the water footprint has remained constant over time and we did not include the grey water footprint, which is the volume of freshwater required to assimilate pollutants to meet a specific water quality standard. Globally, around 6.96 km3 of water is used or the equivalent of around 2.82 million Olympic size swimming pools (assuming a volume of 2500 m3 each) for avocado production in 2018.

Among the top producing countries, Mexico had the largest water footprint (Figure 2), a country where in just two decades water consumption doubled and water stress conditions are clearly associated with physical and economic stress (Oswald Spring, 2011). Interestingly, Chile (ranked 9 in production) ties with Brazil in its overall water footprint (Figure 2), although Brazil has almost double the level of Chile's production. The blue water footprint from agricultural production in Chile is mainly concentrated in the northern dry Pacific and Central areas where less water is available (Donoso et al., 2015). In fact, from the three main avocado growing regions in Chile, the basins of the Petorca and La Ligua rivers became a symbol for the ‘war on water’ in a country where water rights can be transferred from the state to private entities without restrictions. Production fell by 46 per cent in 2018 compared with its maximum in 2009, suggesting the existence of water stress.

Socio-economic impacts

In Mexico where avocados are considered as ‘green gold’ and production takes place over the whole year, around 160 kha are dedicated to its production with most of the plantations being concentrated in the state of Michoacán, which accounted for around 80 per cent of the total production in 2017. In this region, the area dedicated to the production of avocados has increased in 36 years by around seven-fold. Not surprisingly, a significant area of native forest has been converted into avocado fields. Further, the increase in illegal avocado farming has caused increasing and uncontrolled deforestation in Mexico (https://repository.law.miami.edu/umialr/vol49/iss1/6).

The increased focus on export-based production, and thus outside of the reach of many locals (where avocado has strong cultural ties), has also posed questions over regional food accessibility. Subsistence crops have been pushed on to more marginal land (some of which was previously forested) to expand avocado plantations. This marginal land tends to be less fertile and therefore less productive, leading to food insecurity in the local region. Nevertheless, avocado production (specifically the Haas variety) is increasingly seen as a lucrative and attractive industry in Michoacán and this activity has brought increased wealth to the region. More than 40,000 permanent jobs are associated with avocado production in Michoacán with an additional 60,000 seasonal jobs (Echánove, 2008). Wages in the avocado plantations of Michoacán are considerably higher than for other low-skilled jobs in the region. A plantation worker can earn US$ 60 per day, which is significantly higher than the US$ 5 minimum wage in Mexico, making the work very attractive. That said, Mexican avocado production is dominated by larger agribusinesses with 60 per cent of Mexican avocado exporting farmers classified as medium and large producers and many of the smaller farms have been bought out by larger enterprises looking to expand (Echánove, 2008). In 2018/2019, Mexican avocado exports totalled US$ 2.8 billion (USDA: https://gain.fas.usda.gov/#/) and the potential profit has led to a number of regional drug cartels moving into the avocado business. According to Kahn (2018), the region has seen a marked surge in violence with gangs extorting farmers for protection and also threatening USDA inspectors in the country.

Towards sustainable production

It is evident that increasing demand and production of avocados is already causing water stress conditions in some countries, and has the potential to affect many others. Achieving more sustainable production methods with lower water use is crucial considering that water supplies, for example, from glacier melt waters will decrease soon in many regions of the world especially in the subtropical and tropical zones, where cultivation of avocados is widespread. Further, global groundwater resources have been rapidly depleted in semi-humid and arid areas (Wada et al., 2010), while in many regions of the world where avocados are grown, for example the Mediterranean region and California, drier conditions and water stress are on the increase due to climate change (Iglesias and Garrote, 2015; Prein et al., 2016). Although crop production regulates itself when a resource such as water is limiting, for example, during extended drought periods, the impact on the environment and humans takes place before its use crosses critical boundaries. This is because overuse of water for irrigation in agriculture restricts the availability of this resource for human consumption and other ecosystem services. Current avocado production has a significant impact on water access for local communities and is thus generating water stress. In the Michoacán region, for example, as water becomes more limited as a result of climate change and increased agricultural use, there are growing concerns about how to ensure equitable access for local communities and avoid rising tensions from these inequalities of access (Powers, 2019). Already two-thirds of the global population lives under severe water scarcity for at least one month of the year (Mekkonen and Hoekstra, 2016). Further, given the UN's commitment in their Sustainable Development Goals to achieving universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water by 2030, nation states are required to assess their water impacts across all industries, including agriculture. Although there is growing attention to the social justice aspect associated with virtual water (also known as water embedded in products), when this is exported, the result is that it creates an exploitative trade imbalance where already water stressed poorer nations become further depleted when their natural resources are massively extracted and exported.

Road map to sustainability

A road map needs to bring together authorities and policymakers, large and small producers, as well as communities from areas with present and future water scarcity to develop a strategic action plan. They should assess, well in advance, the critical capacity of production of water-intensive agricultural crops in general and of avocado in particular, as depicted by the OECD (2017). This road map also needs to consider near-future climate change scenarios and the complexities in evaluating agricultural water demand to sustain nutritionally adequate human diets. The reality of creating such a road map to address water stress from agricultural production is particularly challenging in countries with currently difficult political situations. However, this is where governments in the richer avocado importing countries can act to facilitate and support such a strategic action plan. For example, the newly signed EU–Mexico trade agreement is a good initiative and potential framework that also includes objectives on sustainable development, environmental standards and working conditions.

We also emphasise that large companies with higher capacity to respond to water stress conditions should not endanger small farmers. Large agribusinesses need to have greater responsibility for the downstream impact of their water extraction. In addition, the EU and other large importers need to consider the environmental footprint of avocados when deciding from where to import. We think the need for a road map is crucial not only because the global economic market for avocados continues to expand, but also because the area dedicated to its cultivation has increased from 66.7 kha in 1980 to 231.5 kha in 2018 (Global Agricultural Data and Analytical Software, https://gro-intelligence.com/).

The environmental and socio-economic issues related to avocado production should be carefully monitored. This would include new areas of production such as in Africa where Kenya nearly reached the levels of Brazil in 2018 and in China where production increased seven-fold between 1992 and 2018. Areas of avocado production with current and future severe water risk include Mexico, Chile, Peru, United States, Israel and Spain (OECD, 2017).

The primary form of export-based production has been through plantations where avocados are grown in monoculture. This type of agriculture is associated with high water usage due to a heavy reliance on irrigation systems and management practices that degrade soil quality and thus, its water-holding capacity. Furthermore, monoculture production causes other environmental impacts due to the excess use of inorganic fertilisers and pesticides. Therefore, producing organic avocados in Spain, Peru and California, for example, needs to be considered, since water quality deterioration is considerably lower than in conventional agriculture.

Need for urgent measures

Our analysis has shown that demand for avocados among western populations has caused an exponential increase in production since the 1990s. This production is largely based in countries outside the large consumer markets and some of them such as Mexico and Chile show clear water stress problems and are experiencing profound negative social consequences. These problems call for urgent counter measures by governments in both avocado producing and importing countries. We would argue also that it would be beneficial for consumers to get involved through buying sustainably produced avocados.

“The environmental and socio-economic issues related to avocado production should be carefully monitored.”

“Les problèmes environnementaux et socio-économiques liés à la production d'avocat doivent être soigneusement surveillés..”

“Die umweltbezogenen und sozio-ökonomischen Fragen im Zusammen-hang mit der Avocadoproduktion sollten genau untersucht werden.”

Funding

This work did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgements

We thank Arjen Y. Hoekstra for advising on the proper use of water footprint values.