Will a No-deal Brexit Disturb the EU-UK Agri-food Trade?

Un Brexit sans accord perturbera-t-il le commerce agroalimentaire entre l'Union européenne et le Royaume-Uni ?

Wird ein No-Deal-Brexit den Handel zwischen der EU und Großbritannien im Agrar- und Lebensmittelbereich beeinträchtigen?

Summary

enThe UK's decision to leave the European Union (EU) marks a turning point in the history of the EU. We analyse the impacts of an exit with no deal on agri-food trade using the temporary customs duties on imports announced by the British government. We focus on three product groups highly traded between the EU and the UK: wine, cheese and meat preparations. First, we show that a no-deal Brexit will put pressure on EU food producers exporting to the UK, Ireland being the most exposed. Second, impacts differ across products. The EU is a key wine supplier to the UK, but the expected removal of import tariffs may permit New World suppliers to grab market shares. The UK is also highly dependent on the EU for its imports of cheese. In the case of a no-deal, EU producers will face increased competition from third country producers of cheese varieties without geographical indications. The EU exports of meat preparations seem the most affected by a no-deal Brexit. In addition to the strong position of some non-EU suppliers on the British market, which will continue to enjoy a preferential market access, the UK's tariffs on meat products imported from the EU will rise sharply.

Abstract

deLa décision du Royaume-Uni de quitter l'Union européenne (UE) marque un tournant dans l'histoire européenne. Nous analysons les effets d'une sortie sans accord sur le commerce agroalimentaire en employant les droits de douane temporaires sur les importations, annoncés par le gouvernement britannique. Nous nous concentrons sur trois groupes de produits fortement échangés entre l'UE et le Royaume-Uni: le vin, le fromage et les préparations à base de viande. Premièrement, nous montrons qu'un Brexit sans accord pèsera sur les producteurs de denrées alimentaires de l'UE exportant vers le Royaume-Uni, l'Irlande étant le pays le plus exposé. Deuxièmement, les impacts diffèrent d'un produit à l'autre. L'UE est l'un des principaux fournisseurs de vin du Royaume-Uni, mais la suppression attendue des droits de douanes à l'importation pourrait permettre aux fournisseurs du Nouveau Monde d'obtenir des parts de marché. Le Royaume-Uni est également fortement dépendant de l'UE pour ses importations de fromage. En cas d'absence d'accord, les producteurs de l'UE seront confrontés à une concurrence accrue des producteurs de types de fromage de pays tiers sans indication géographique. Les exportations de préparations à base de viande de l'UE semblent être les plus touchées par un Brexit sans accord. Outre la forte position de certains fournisseurs non européens sur le marché britannique, qui continueront à bénéficier d'un accès préférentiel à ce marché, les droits de douane appliqués par le Royaume-Uni aux produits carnés importés de l'UE augmenteront fortement.

Abstract

frDie Entscheidung des Vereinigten Königreichs, die Europäische Union (EU) zu verlassen, markiert einen Wendepunkt in der europäischen Geschichte. Wir analysieren die Auswirkungen eines Ausstiegs ohne Abkommen auf den Agrar- und Lebensmittelhandel unter Verwendung der von der britischen Regierung angekündigten temporären Zölle auf Einfuhren. Wir konzentrieren uns auf drei Produktgruppen, die zwischen der EU und dem Vereinigten Königreich intensiv gehandelt werden: Wein, Käse und Fleischerzeugnisse. Erstens zeigen wir, dass ein No-Deal-Brexit Druck auf die EU-Lebensmittelhersteller, die nach Großbritannien exportieren, ausüben wird, wobei Irland am stärksten betroffen sein wird. Zweitens sind die Auswirkungen von Produkt zu Produkt unterschiedlich. Die EU ist ein bedeutender Weinlieferant des Vereinigten Königreichs. Die zu erwartende Abschaffung der Einfuhrzölle könnte es jedoch den Lieferanten aus Nord- und Südamerika ermöglichen, Marktanteile zu gewinnen. Auch bei der Einfuhr von Käse ist das Vereinigte Königreich in hohem Maße von der EU abhängig. Im Falle eines No-Deals werden Produzenten aus der EU einem verschärften Wettbewerb mit Erzeugern von Käseprodukten ohne Herkunftsangabe aus Drittländern ausgesetzt sein. Die Exporte von EU-Fleischerzeugnissen scheinen am stärksten von einem No-Deal-Brexit betroffen zu sein. Zusätzlich zu der guten Position einiger Nicht-EU-Lieferanten auf dem britischen Markt, die auch künftig einen bevorzugten Marktzugang genießen werden, werden die Zölle des Vereinigten Königreichs auf aus der EU eingeführte Fleischerzeugnisse stark ansteigen.

The UK's decision of June 2016 to leave the European Union (EU), and its notification to the EU on 29 March 2017 (Article 50 of the Treaty on EU) marks a turning point in the history of the EU and raises many questions on future economic relationships, especially on the evolution of agricultural and food trade. Following several rounds of Brexit negotiations, the EU-27 and the UK government reached a withdrawal agreement on 25 November 2018 (EC, 2018).1 However, since this announcement, many twists have taken place, the agreement being rejected three times by the UK Parliament (15 January, 12 March and 29 March 2019). At a European summit on 10 April 2019, the European Council decided to extend the date of exit until 31 October 2019. Before this date, the British Parliament could ratify the withdrawal agreement and start negotiations on the future trade relationship with the EU (at time of writing this could still be possible); or it could fail to conclude a deal opening the door to a hard Brexit; or the UK could rescind its Article 50 notification, possibly following a further referendum.

To date, no deal seems the most likely outcome, fueling the fears of a Halloween Brexit, and it is that scenario we examine in this article. To smooth the impacts of such a shock on the British economy, on 13 March 2019, the UK government published the temporary rates of customs duties on imports that would apply if the UK were to leave the EU with no deal (UK, 2009a, see Box 1). Should European agri-food producers exporting to the UK worry about this scenario? We analyse here the potential impacts of the UK's exit from the EU without a deal on agri-food trade. The temporary tariffs concern only 13 per cent of products imported by the UK, but most of them apply to agri-food goods. EU suppliers will lose the preferential access to the British market that have so far benefited from. This will strengthen the trade competition on this market and challenge the future EU-UK trade relationship.

“Un Brexit sans accord pèsera sur les producteurs de denrées alimentaires de l'Union européenne exportant vers le Royaume-Uni, l'Irlande étant le pays le plus durement touché.”

Box 1. The UK's post-Brexit trade policy in a nutshell

Until the UK's exit from the EU, British imports from EU partners are free of tariffs, non-tariff measures and border checks, while imports from non-EU partners are subject to the common EU import tariff and to border checks (quite long and costly, especially for animal products). As an EU member, the UK provides low or even nil tariff rates (on imports) for non-EU countries with which the EU has signed a preferential trade agreement, and applies the higher EU's MFN (most favoured nation) tariff rate to imports from the remaining non-EU partners (the same rate for all). Brexit implies the UK's exit from all EU trade agreements and charging the same tariff rate on imports from all partners, except the ones with which the UK has (would have) signed a trade deal (UK, 2018, 2019b). If no EU-UK deal is reached, imports from EU partners will enter the UK market under the same regime as imports from third countries, both in terms of tariffs and border checks. To limit the disruption of trade relationships, on 13 March 2019 (two weeks before the initial Brexit due date) the British government announced that, in case of a no-deal exit, it will remove tariffs on 87 per cent of the UK's imports (UK, 2019a). On the remaining 13 per cent of products, it will apply a temporary MFN tariff significantly lower than the EU's MFN tariff, for a period up to twelve months. In this case, non-EU suppliers will benefit from improved access to the British market, the effect being strongest for countries currently facing the highest EU import tariff (i.e. that don't have a preferential trade relationship with the EU), such as the US and China. Thus, even if most of the EU-UK trade will remain tariff-free, EU countries will lose their preferential access to the UK market and, most likely, cede some of their market shares to non-EU competitors.

The temporary import tariffs will not apply to goods crossing from Ireland into Northern Ireland, which will continue to be traded freely and without additional border checks. It remains questionable whether this measure in effect grants Irish producers free access to the whole British market. Indeed, they may choose to ship their exports to the rest of the UK through the Belfast harbour or, by displacement, enable trade partners in Northern Ireland to dispatch their products to the rest of the British market. Other countries exporting to the UK may contest this situation of unfair competition to the WTO's dispute settlement authority, although the temporary status of this measure may temper down potential objections.

The interconnection of British and European agri-food sectors

The UK is highly dependent on the EU-27 for its agricultural and food sectors. In 2015, 72 per cent of its agri-food imports by value came from the EU bloc and 59 per cent of British agri-food exports were directed to EU countries (data obtained from the Comext database).

Reciprocally, the UK is a major destination market for EU-27 agri-food products (8.9 per cent of exports), the second largest after Germany and ahead of France (Table 1). When the UK leaves the EU, it will become by far the largest extra-EU export destination of European agri-food products, followed at some distance by the US (4.5 per cent) and China (3.2 per cent). The main products exported by the EU-27 to the UK are meat products (17.5 per cent) and beverages (13.8 per cent), based on 2015 data.

| Country | Share |

|---|---|

| EU-27 (except the UK), of which : | 62.35 |

| Germany | 12.25 |

| France | 7.77 |

| Netherlands | 6.77 |

| Italy | 6.21 |

| Belgium-Luxembourg | 5.25 |

| Spain | 3.82 |

| United Kingdom | 8.88 |

| Rest of the world, of which | 28.77 |

| USA | 4.52 |

| China | 3.17 |

| Switzerland | 1.69 |

| Japan | 1.43 |

| Russian Federation | 1.30 |

At the same time, the UK is not a major agri-food supplier of the EU-27. EU countries source most of their agri-food imports from Netherlands (11.6 per cent), Germany (11.3 per cent) and France (8.1 per cent). Only 3.4 per cent of the EU-27's agri-food imports (mainly strong alcohols, dairy, and fish & sea products) come from the UK, which makes it the EU's 8th supplier in the sector. The value of the UK's agri-food exports to the EU-27 is comparable to that of Poland (7th, 4 per cent), Brazil (9th, 3 per cent), and the US (10th, 2.8 per cent).

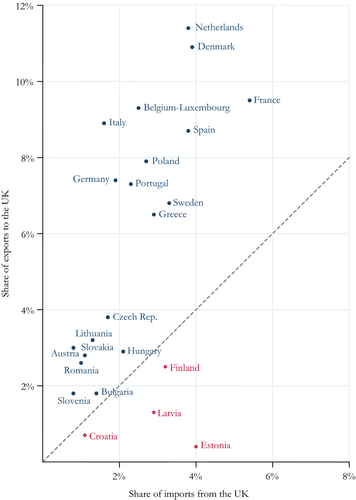

As a result, the EU-27's trade balance with the UK in the agri-food sector is highly positive (US$ 28 billion in 2015). While this feature is common to most EU countries, the relative importance of the British market varies greatly across Member States (Figure 1). Although not shown in Figure 1, Ireland is by far the most dependent on the UK market: 40 per cent of its exports go to the UK (mainly meat products and dairy), and 49 per cent of its imports come from the UK (mainly meat and cereal products). On the opposite side, the UK is only a marginal trade partner for Croatia and Estonia, accounting for less than 1 per cent of their global agri-food exports. The UK has a large global trade deficit in the agri-food sector (US$ 34 billion), most of which (83 per cent) comes from trade with the EU-27.

“Ein No-Deal-Brexit wird Druck auf diejenigen EU-Lebensmittelhersteller ausüben, die nach Großbritannien exportieren, wobei Irland am stärksten betroffen sein wird.”

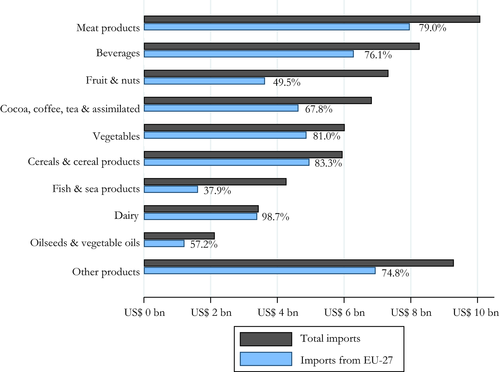

Figure 2 shows the composition of the UK's agri-food imports by broad product groups. The main products imported by the UK are meat products (US$ 10 billion), followed by beverages (US$ 8.2 billion). On average, around 70 per cent of the UK's agri-food imports come from EU partners, but this share varies greatly across product groups (Figure 3). For instance, almost all dairy products imported by the UK come from the EU-27 (98.7 per cent), while the EU-27 supplies less than half of the fruit and nuts (49.5 per cent) and of the fish and sea products (37.9 per cent) imported by the UK.

Note: Bar labels correspond to the share of UK imports from the EU-27 in UK total imports.Source: Authors’ computation using BACI trade database for 2015.

Source: Authors’ computation using BACI trade database for 2015.

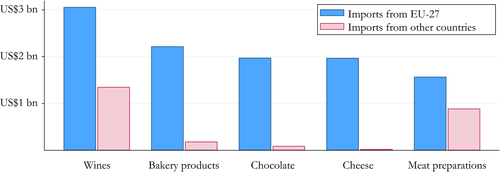

At a more narrow level of disaggregation, five products stand out in the British imports from the EU-27 (Figure 3): wines (over US$ 3 billion), bakery products (US$ 2.4 billion), chocolate and cheese (around US$ 2 billion each), and meat preparations (US$ 1.6 billion). Note that each of these products is a flagship of one of the product categories listed in Figure 2 where the EU-27 has the strongest position on the UK market. There is no representative product for vegetables because the UK imports a large variety of individual products from this category with small weights. Even tomatoes (fresh and chilled), the vegetable that the UK imports the most, lags far behind this top five with only US$ 620 million of annual imports.

Among these five products, the UK is highly dependent on imports from the EU-27 for cheese, chocolate and bakery products, and to a lesser extent for wines and meat preparations. In the rest of the article, we focus on wines (the product with the highest value of EU exports to the UK), cheese (where the EU is a key supplier for the UK) and meat preparations (where the EU faces high competition from non-EU countries). Cheese and meat preparations are also some of the few products on which the UK intends to keep temporary tariffs in case of a no-deal Brexit (Table 2). This decision, aimed at protecting the British cheese and meat producers, signals that these goods will play an important role in the UK's negotiations of future trade agreements.

| EU's average MFN tariff | UK's average temporary MFN tariff | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ad-valorem | Specific | Ad-valorem | Specific | |

| Wine | 0.00% | 10.74 € /hl | 0.00% | 0 |

| Cheese | 0.00% | 1685 €/1000kg | 0.00% | 80 €/1000kg |

| Bakery products | 8.44% | 7.09 €/1000kg | 0.00% | 0 |

| Meat preparations | 2.39% | 1325 €/1000kg | 0.01% | 609 €/1000kg |

| Chocolate | 8.35% | 1.02 €/1000kg | 0.00% | 0 |

Note

- Weighted means of EU and UK tariffs at a narrower product level using trade as weights (see Box 2). Average tariffs mask the heterogeneity observed at product level, especially for the UK's temporary MFN tariffs. For a specific product, the ad-valorem equivalent of the two MFN tariff types (ad-valorem and specific) may differ across source countries due to differences in the structure and price of imports.

Box 2. Import tariffs explained

Import tariffs are set as a percentage of the value of traded goods (ad-valorem duties), as a monetary amount on a physical quantity (specific duties), or as a combination of the two. Two sources of tariff data were employed: the UNCTAD Trade Analysis Information System (TRAINS) database, and the Integrated Tariff of the European Union (TARIC) database. The TRAINS database provides an ad-valorem equivalent of all tariffs (ad-valorem and specific) applied to a specific trade flow at a 6-digit classification of products. The TARIC database provides detailed import duties on EU imports from each partner at an 8-digit and a 10-digit classification of products. Each product analysed in the text (wine, cheese, meat preparations, bakery products, and chocolate) corresponds to a unique 4-digit code. Tariffs applied on these products were computed as a weighted mean of TRAINS tariffs using the UK's imports at the 6-digit level as weights. The EU's ad-valorem and specific tariffs on each product were computed as a weighted mean of TARIC tariffs using the UK's imports at the 8-digit level as weights (Table 2).

Wines: the most exported EU product to the UK.

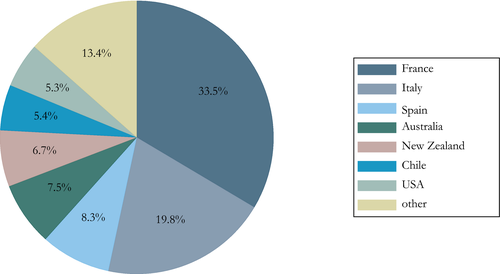

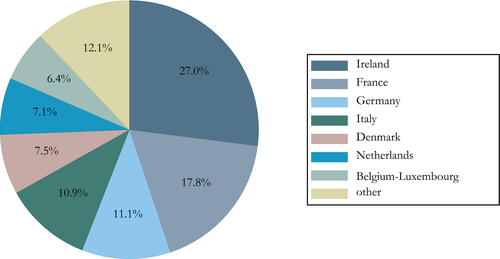

The UK imports nearly 70 per cent of its wine from EU partners (Figure 4), the top three suppliers being France (33.5 per cent), Italy (19.8 per cent) and Spain (8.3 per cent). The EU's main competitors on this market are New World wine producers (Australia, New Zealand, Chile, USA, South Africa, Argentina). The UK's tariffs on imports from these countries currently amount to a 2.96 per cent to 5.96 per cent ad-valorem equivalent, unlike EU wines that are traded freely. Reducing or removing these tariffs, in line with the temporary rates announced by the British government (Table 2), will reinforce the competition on the UK market. Benefiting from an improved market access, New World suppliers may lower prices and capture market shares from EU exporters.2 In addition, the UK is a key destination for the largest New World competitors, absorbing 25 per cent of New Zealand's, 19 per cent of South Africa's, and 17 per cent of Australia's wine exports. This condition may encourage them to adopt more aggressive strategies in order to increase their market shares. Within the EU, France and Italy depend the most on the UK market, both shipping over a fifth of their exports of wine to the UK. After Brexit, the EU wines that could be displaced from the UK market are likely to be reoriented to the US and Germany, the largest and the third-largest export destinations of European wines, respectively. Unlike the US, where EU wines face a moderate 2.74 per cent import tariff, other large non-EU importers charge much higher tariffs (14.17 per cent by China, 22.28 per cent by Japan, 25.60 per cent by Switzerland), making it more difficult to reorient the excess EU supply to these markets.

Source: Authors’ computation using BACI trade database for 2015.

Cheese: a product that the UK imports almost exclusively from EU partners.

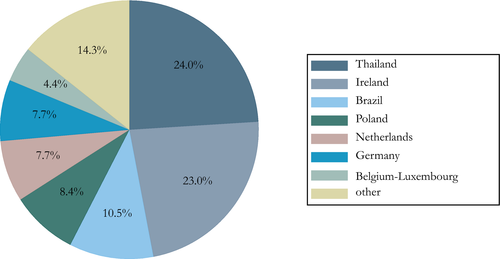

Similarly to other dairy products, the British imports of cheese arrive almost exclusively from EU partners (Figure 5). Ireland is the UK's main supplier of cheese with a market share of 27 per cent, followed by other large European producers. The very low level of British imports from non-EU countries is partially due to the high EU tariff: an ad-valorem equivalent of 19.01 per cent on imports from Australia and New Zealand, 36.59 per cent on imports from Norway, and 42.03 per cent on imports from the US. In case of a no-deal Brexit, these tariffs will be strongly reduced, allowing cheese producers from these countries to increase their presence on the British market and challenge the EU's dominant position.3 However, the heterogeneity of cheese products may attenuate the competition.

Source: Authors’ computation using BACI trade database for 2015.

The EU cheese industry is characterised by the presence of a large number of products with protected names based on geographical indications (GI). GI protection represents an important element of the EU's policy in the agri-food sector. It offers not only an additional shield against competition, but also the possibility to charge a price premium (Box 3). The UK's intention to mirror the EU's scheme of products with GI protection will preserve the capacity of European GI cheese producers to differentiate their products from those of competitors and maintain a price gap, even in case of a no-deal Brexit. For products with no GI protection, British consumers may switch quite easily to lower-priced varieties from outside of the EU. Thus, in the case of a hard Brexit, more varieties like US-produced Mozzarella and Cheddar will lie on the table of Britons, cheesing-off some of the European (and possibly even British) producers. The increased competition from third country producers will primarily affect the Member States that export mostly non-GI protected cheeses (Ireland, Denmark, Germany and the Netherlands), and to a lower degree the EU countries exporting a higher share of GI-protected cheeses (Greece, Italy and France).

“A no-deal Brexit will put pressure on EU food producers exporting to the UK, Ireland being the most severely affected.”

Box 3. Geographical Indications

Geographical Indications (GI) are a form of intellectual property protection that identifies a product as originating in a country, region or locality where a given quality, reputation or other characteristic of the product are attributable to the place where it is produced (Marie-Vivien and Bienabe, 2017). GI are a central issue in the EU's recently signed trade agreements (e.g. CETA, with Canada) and on-going trade negotiations (e.g. with South Korea, Japan, Australia) in the agri-food sector. The EU legislation on GI forbids the sale of products with identical names from other sources (e.g. non-Italian Gorgonzola, non-Greek Feta, and non-British Stilton cheeses). It also promotes the perception of GI as an indicator of high quality, which permits the sale of GI protected goods at a higher price. The UK has an incentive to continue to respect the EU legislation on GI, since it has an important number of its own GI-protected goods. A total of 86 British products are registered under the EU's GI schemes, including 15 cheeses and five spirit drinks. Cumulatively, these products represent 25 per cent of the UK's agri-food exports by value. Scotch Whisky alone accounts for most (over three fourths) of the UK's exports of GI protected goods.

Within the EU, Irish cheese producers are the most dependent on the UK, with 60 per cent of their exports concentrated on this market, mostly non-GI protected. Other EU countries have a more balanced distribution of exports across trade partners (with only 4.5 per cent of the Dutch and as much as 14.3 per cent of the Greek exports of cheese being shipped to the UK), making it less painful to reorient to third markets the products that after Brexit they will not be able to sell to British consumers. European producers trade around 90 per cent of their cheese on the intra-EU market. Therefore, one can expect that they will compensate for a decrease in the British demand for EU products mainly by increasing exports to EU partners. They have already adopted this strategy in response to recent policy shocks, including the Russian food embargo and the end of EU milk quotas. Exporting larger amounts to EU partners will also put a downward pressure on EU prices, which may in the end improve the EU's competitive position with respect to the UK and non-EU suppliers. This secondary price effect merits a deeper analysis, which exceeds the scope of the current assessment.

Meat preparations: a sector where EU exports to the UK compete heavily against third countries.

The British market for meat preparations is notable for the strong presence of non-EU exporters (Figure 6). Thailand, with a share of 24 per cent, is the UK's main supplier on this market, outpacing Ireland (23 per cent), and followed at some distance by Brazil (10.5 per cent). Most (95 per cent) of the Thai exports and half of the Brazilian exports in this product group consist of cooked chicken meat, imported at low preferential rates within tariff-rate-quotas (TRQs) these countries benefit from on the EU market. The two countries are the UK's main suppliers of poultry preparations (55 per cent). On the contrary, two-thirds of bovine meat preparations are imported from the EU and one third from Brazil, and swine meat preparations are imported exclusively from European partners. The UK announced its intention to keep the same preferential tariffs on poultry imports from Thailand and Brazil, but the announced TRQs on its main imports from these countries are below its current level of imports (UK, 2019c). Thailand will be more severely impacted by this change as half of its exports to the British market will become subject to the higher out-of-the-quota (MFN) tariff rate. This may generate up to a 6 per cent increase in the price of the UK's imports of Thai cooked chicken meat, questioning the redistribution of market shares in case of a hard Brexit. Thus, European producers are not much threatened by the competition of Thailand and Brazil on this segment of the market. Currently, Brazilian producers of bovine meat preparations experience a lower access to the UK market (a 16.6 per cent tariff rate) than their European rivals (tariff-free access). In the case of a hard Brexit, this gap will close down, import tariffs shifting to 8.8 per cent for all suppliers. This may weaken the position of EU exporters. Over the entire market for meat preparations, the tariff on imports from other countries (the UK's MFN tariff) will be cut by half (Table 2) allowing new suppliers to enter the British market.

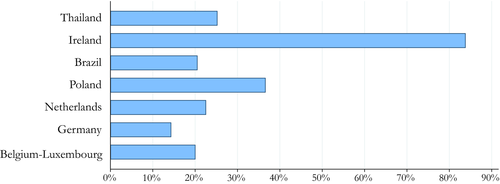

Source: Authors’ computation using BACI trade database for 2015.

Despite the fact that most EU countries account for small shares in the UK's imports of meat preparations, the British market is a major destination of their exports: e.g. 23 per cent for the Netherlands, 37 per cent for Poland, and 84 per cent for Ireland (Figure 7). The UK is the first export market for European exports in this sector (as a bloc), well ahead of other markets. This makes the EU meat sector even more alert to post-Brexit policy changes. The main countries towards which European meat producers could reorient their exports are within the EU, their exports to third countries being marginal (only 2.7 per cent to China and 1.4 per cent to the US). However, the tougher competition they will face on the British market may force them to become more proactive and engage in selling more to extra-EU partners.

Source: Authors’ computation using BACI trade database for 2015.

Pressure on EU food producers

This article has investigated how the UK's exit from the EU might affect three groups of products most intensively traded between the EU and the UK: wine, cheese and meat preparations. The latter two are among the few products on which the UK intends to keep temporary import tariffs if it leaves the EU with no deal. The analysis shows that a no-deal Brexit will put pressure on EU food producers exporting to the UK, Ireland being the most severely affected. This finding is in line with Bellora et al. (2017) and Dhingra et al. (2017) that highlight the high costs of Brexit for the Irish economy.

The EU is a key wine supplier to the UK, but the announced removal of the UK's imports tariffs may permit New World suppliers to capture larger market shares. The UK is also highly dependent on the EU for its imports of cheese. In the case of a no-deal, EU cheese producers will face increased competition from third country producers of cheese varieties without GI protection. However, the heterogeneity of cheese products may attenuate this effect. The EU-UK trade in meat preparations seems to be the most severely affected by a no-deal Brexit. In this sector, EU producers are confronted with strong positions of some non-EU suppliers who will continue to benefit from preferential access to the British market. Under no-deal, the UK will cut by half its import tariffs on meat products from outside the EU, while tariffs on EU products will increase sharply. Our results on meat preparations support the finding by Van Berkum et al. (2016) that a hard Brexit will deteriorate the UK's net trade position for animal products due to higher imports of livestock products from outside the EU.

Similarly to this article, the few recent studies that attempt to measure the impacts of a hard Brexit on trade between the UK and EU Member States show a strong heterogeneity of effects across sectors and countries. For example, Erken et al. (2018) find important changes in the volume of global trade whatever the scenario, the negative impact being stronger under a hard Brexit scenario.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Alan Swinbank and an anonymous referee for very helpful comments on an earlier version of the paper and to Lucile Henry for assistance on data treatment.