Testing the underdog entrepreneurship theory with specialised Australian immigrant data

Funding information: This study was supported by the Australian Research Council (DP170101726).

Abstract

Migrants account for a significant proportion of the Australian workforce, and for many entrepreneurs in its business sector; but they experience difficulties due to language, culture shock, family separation, social exclusion, disability, poverty, and discrimination—across cohorts, visa streams, and geographical locations. Their entrepreneurship choices are conditioned by demographic, socioeconomic, and contextual factors; but little is known about how these choices are affected by migration status, gender, socioeconomic and demographic adversity, and geographic location in their new country. Using the 2021 Australian Census and Migrants Integrated Dataset (ACMID), we examine how these factors influence entrepreneurship choices and preferences for owning incorporated versus unincorporated businesses among permanent migrants arriving in Australia between 2000 and 2021. We analyse relationships between entrepreneurship and demographic, socioeconomic, and contextual factors, distinguished by gender and applicant status, and construct a two-stage conceptual framework and two-step multilevel econometric models to decompose entrepreneurial outcomes that consider various effects. Our quantitative study yields important new evidence and advances knowledge concerning demographic and economic processes, with policy implications at micro and macro levels for inclusive and sustainable economic growth, employment levels, and decent work trajectories.

Key insights

This study examines determinants of permanent migrants’ work choices in Australia—wage employment versus diverse entrepreneurial pathways. Leveraging the recent Australian Census and high-quality immigration data, we analyse key factors and their complex interactions. We assess Miller and Le Breton-Miller’s (2017) underdog entrepreneurship theory, finding some good support in the Australian context while proposing theoretical extensions. Future research should employ longitudinal datasets to better identify causal mechanisms and enrich policy insights for migrant economic participation.

1 INTRODUCTION

Migration is important to Australia, and other high-income countries, as it fosters population growth, supports labour force participation and productivity, and helps offset population ageing (Kirchner, 2020; The Treasury, 2023). Net overseas migration accounted for over 60% of Australia’s population growth of 3.7 million over the last decade, and this figure is projected to increase to about 70% by 2062–63 (The Treasury, 2023). Doubling over the last 50 years, immigration has accounted for a large part of Australia’s current population. More than a quarter (28%) of the Australian population were born overseas, and 24% of Australian-born people have at least one parent born overseas (ABS, 2023). Permanent immigrants come to Australia under four capped programs: Skilled, Family, Special Eligibility, and increasingly the Humanitarian program. Each program comprises various visa categories (DHA, 2024). The 2021 Australian Census and Migrants Integrated Dataset (ACMID) shows that 59% of permanent migrants (totalling 3.0 million) arriving between 1 January 2000 and 10 August 2021 (Census night) came under a range of Skilled visa schemes, 32% came under the Family program, and 9% under the Humanitarian program (ABS, 2023). Of these permanent migrants, 58% were primary visa applicants, and the remainder were secondary. A secondary applicant is a family member of a primary applicant: a spouse, an interdependent partner, a dependent child, or some other dependent relative.

Immigration has long been a catalyst for innovation and entrepreneurship in traditional immigrant-receiving nations such as the US, Canada, Australia, and Germany (Kirchner, 2020). In Australia and other OECD countries, immigrants exhibit a significantly higher propensity than natives to engage in entrepreneurship—whether as sole proprietors or employers in incorporated or unincorporated ventures (Mestres, 2010). Remarkably, one-third of Australia’s small businesses (at least 620,000) are migrant owned, with 83% of these owners establishing their enterprises post-arrival (CGU, 2017). These businesses are not only more dynamic in job creation, innovation, and revenue growth but also employ 1.4 million workers, accounting for 28% of Australia’s small-business workforce. Their ambitious growth plans, including an estimated 200,000 new jobs within 5–10 years (CGU, 2017), underscore their critical role in the economy.

Yet, entrepreneurship among immigrants is far from homogeneous. Systematic literature reviews reveal stark variations in entrepreneurship strategies, types, and outcomes across immigrant groups (Gurău et al., 2020; Malerba & Ferreira, 2021; Sithas & Surangi, 2021). Scholars urge deeper comparative analyses—both within and between immigrant cohorts in host countries—and call for examining demographic, psychographic, and cultural factors that shape entrepreneurial behaviour (Malerba & Ferreira, 2021). Equally critical is understanding why some immigrants refrain from entrepreneurship altogether, including constraints in launching or sustaining ventures (Gurău et al., 2020).

A pivotal but understudied dimension is the choice between incorporated and unincorporated business structures among Australia’s diverse immigrant entrepreneurs. This distinction carries profound implications: incorporated entities (for example, proprietary companies) offer liability protection and access to capital but entail complex compliance, while unincorporated ventures (for example, family partnerships) prioritise flexibility at the cost of personal risk. These structural differences shape risk-taking, financial strategies, and long-term viability, yet their drivers and consequences remain poorly understood. By dissecting this dichotomy, our study addresses a gap in the intersection of migration and entrepreneurial behaviour research, offering actionable insights for policymakers and stakeholders aiming to harness migrant entrepreneurship’s full potential.

This study leverages rich information from the 2021 ACMID data to advance the understanding of immigrant entrepreneurship. Combining detailed information on permanent migrants’ visa class, employment status, and socioeconomic characteristics with geographic data on host communities, we provide the first comprehensive analysis of factors influencing entrepreneurship choices among Australia’s immigrant population (2000–2021). We employ innovative two-stage multilevel econometric models to differentiate between employment, incorporated business ownership, and unincorporated business ownership—a crucial but understudied distinction in migration research. We examine how these outcomes vary across seven visa categories (Skilled: Independent, Government-sponsored, Employer-sponsored, Business; Family: Partner, Parent/Other; Humanitarian) while accounting for gender and primary/secondary applicant status. We incorporate contextual factors, including local socioeconomic advantage/disadvantage—a novel approach in this literature.

RQ1: How do migration status, demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, and geographic-contextual settlement factors differently shape the choice between wage employment and business ownership among diverse immigrant groups in Australia (disaggregated by gender and visa category [primary versus secondary applicants])?

This study advances scholarship at the nexus of demography, human geography, and entrepreneurship through four significant contributions. First, we address a critical gap in quantitative research on Australian migrant entrepreneurship by leveraging the newly released 2021 ACMID data. Our analysis focuses on permanent immigrants aged 16–69 who had settled in Australia for 1–16 years at the 2021 Census time, providing novel insights into how micro-, meso-, and macro-level demographic, social, and economic factors shape entrepreneurial outcomes. The ACMID’s comprehensive coverage is particularly valuable for capturing underrepresented groups in migration programs—a limitation pervasive in conventional social surveys (McLachlan et al., 2013). Second, we bridge theoretical divides by integrating underdog entrepreneurship theory (Miller & Le Breton-Miller, 2017) with classical social- and human-capital frameworks (Gurău et al., 2020). Our two-stage analytical model elucidates how migration adversity—often overlooked in prior work—directly influences entrepreneurship choices, including the critical distinction between incorporated and unincorporated ventures. This empirically validates and extends underdog theory’s applicability to migration contexts. Third, we pioneer an intersectional analysis of how visa status, socioeconomic disadvantages (measured through social and human capital), geographic settlement patterns, and community-level advantages/disadvantages interact with gender and applicant status (primary/secondary) to shape entrepreneurial pathways. These findings redefine conventional narratives about immigrant entrepreneurship determinants. Fourth, we translate robust evidence into policy solutions. By quantifying how migration experiences affect economic participation, our study equips policymakers to align Australia’s migration and entrepreneurship ecosystems—advancing UN Sustainable Development Goal 8 (decent work and inclusive growth). Globally, these insights offer a blueprint for leveraging migration as a catalyst for equitable development.RQ2: How do these factors further differentiate immigrant entrepreneurs into incorporated versus unincorporated enterprises?

Following this introduction, Section 2 synthesises key strands of the literature on the nexus between migration, employment, and entrepreneurship. Section 3 briefly outlines our conceptual framework and data. Section 4 presents our two-stage multilevel econometric modelling approach, introduces how to apply our framework to examine the associations empirically based on the 2021 ACMID microdata, and defines the key variables (outcomes and predictors) that we subjected to quantitative analysis and econometric modelling. Section 5 presents the main empirical results of our econometric analysis. Section 6 extracts theoretical and policy implications and mentions some limitations and possible extensions of this study, and Section 7 assembles more general conclusions and implications.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW: THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN IMMIGRATION, IMMIGRANT ENTREPRENEURSHIP, AND KEY DETERMINANTS

2.1 Immigrant entrepreneurship: theoretical perspectives

The determinants of immigrant entrepreneurship have been extensively theorised through multiple lenses. Kloosterman and Rath’s (2001) mixed embeddedness theory provides a foundational framework, positing that immigrant economic activities are shaped by the interplay of institutional (political) and economic (market) contexts. This theory identifies three critical opportunity structures: economic conditions (for example, privatisation trends), market entry thresholds, and growth potential (Kloosterman & Rath, 2018). While valuable for analysing industry-specific development, the theory’s macro-level focus often overlooks micro-level decision-making processes, particularly how individual migrants navigate these structural constraints (Solano, 2020). Recent work has attempted to bridge this gap, but significant theoretical and empirical challenges remain in understanding how meso-level factors (for example, local community networks) mediate between structural constraints and individual agency.

Social capital theory offers crucial insights into how migrants overcome resource constraints. Putnam’s (1995) conceptualisation of social capital as norms, networks, and trust has been particularly influential in migration studies. Research identifies three network types critical for migrant entrepreneurs: bonding ties (strong, homogeneous connections), bridging ties (weak, heterogeneous connections), and linking ties (vertical power relationships) (Putnam, 2000). While bonding capital helps migrants access informal resources (Bagwell, 2018), excessive reliance on co-ethnic networks can create enclave economies with limited growth potential (Flap et al., 2000). This paradox remains under-theorised, particularly regarding how different migrant groups transition from bonding to bridging capital. Malerba & Ferreira’s (2021) finding about the premium of dual-country networks suggests promising directions for future research, yet their work lacks granularity about network formation processes.

The literature identifies four dominant immigrant entrepreneurial pathways (Gurău et al., 2020): ethnic enclave entrepreneurs (32%), transnational intermediaries (25%), transcultural entrepreneurs (21%), and knowledge-based entrepreneurs (16.7%). While this typology usefully categorises outcomes, it inadequately explains the mechanisms behind pathway selection. Notably absent is rigorous analysis of how visa categories or migration streams (for example, Skilled vs. Humanitarian) predispose migrants toward particular entrepreneurial trajectories—a critical gap our study addresses.

Human capital factors demonstrate equally complex dynamics. Becker’s (1994) framework has guided extensive research showing that host-country-specific human capital—particularly language proficiency and local qualifications—strongly predicts entrepreneurial success (Chen et al., 2019; Williams & Krasniqi, 2018). However, three significant limitations persist. First, most studies treat human capital as static, ignoring its accumulation trajectories post-migration. Second, the assumed linear relationship between education and entrepreneurship fails to account for credential discounting effects (Fortin et al., 2016). Third, emerging evidence about mental health mediators (Cheng, Wang, et al., 2021) suggests current models may oversimplify the human capital-entrepreneurship nexus.

Current theoretical perspectives predominantly focus on positive individual and contextual factors (for example, financial, social, and human capital) in fostering migrant entrepreneurship. This optimistic framing overlooks how adverse circumstances may equally drive entrepreneurial behaviour—a critical gap addressed by Miller and Le Breton-Miller’s (2017) underdog entrepreneurship theory. Their framework posits that economic precarity, sociocultural marginalisation, and physical/emotional challenges can cultivate adaptive traits like risk tolerance, creativity, and networking skills that enable entrepreneurial success. While compelling, this theory remains under-tested in migration contexts, with existing studies largely limited to descriptive explorations (Sithas & Surangi, 2021).

Three key limitations persist: (1) overemphasis on individual agency at the expense of structural constraints; (2) inadequate attention to how visa categories, migration pathways, and geographic settlement patterns moderate adversity effects; and (3) lack of quantitative validation using comprehensive migrant datasets. Our study addresses these gaps by rigorously testing underdog theory with Australia’s 2021 ACMID data—offering systematic evidence on how adversity interacts with institutional factors to shape entrepreneurial outcomes among diverse migrant groups.

2.2 Immigrant entrepreneurship and adversity

Recent scholarship highlights that migrants facing systemic adversities—such as chronic poverty, gender discrimination in patriarchal communities (Shepherd & Williams, 2020), mental health challenges (Wiklund et al., 2018), disability (Hsieh et al., 2019), or exposure to extreme shocks (for example, natural disasters, business failures)—demonstrate a heightened propensity for entrepreneurship. However, the literature largely overlooks critical heterogeneity in migration experiences, with few exceptions (for example, Cheng, Guo, et al., 2021; Hayward et al., 2022). Variations in migration status, individual and familial circumstances, and geographic contexts remain underexplored, limiting our understanding of how divergent structural constraints shape entrepreneurial outcomes.

Longitudinal research in Australia reveals stark disparities in entrepreneurial entry among migrant subgroups. Refugees, for instance, confront compounding disadvantages—financial precarity, residential segregation, and labour market exclusion—which suppress both wage employment and entrepreneurship. Only 1% of a recent refugee cohort initiated businesses within their first four years of settlement (Cheng, Wang, et al., 2021). Humanitarian migrants with unpaid work experience, job-search skills, and better health are more likely to enter employment than self-employment (Cheng, Wang, et al., 2021; Khoo, 2010). Yet, key questions persist: How do social and human capital factors (for example, labour market engagement, unpaid caregiving, familial disability, or post-migration occupational shifts) differentially influence entrepreneurship across migrant populations? This paper addresses this gap by examining how intersecting vulnerabilities and resources shape entrepreneurial pathways.

Australia’s migration system creates distinct entrepreneurial trajectories. Humanitarian and Family visa holders typically enter with lower socioeconomic capital and labour market participation than Skilled migrants (Productivity Commission, 2016). While refugees initially face steep employment barriers, intergenerational progress often mitigates these disadvantages (Hugo, 2014). In contrast, Business migrants arrive with substantial financial, social, and human capital, often mandated by visa requirements (for example, minimum investment thresholds). These migrants leverage multi-scalar networks—micro (household), meso (community), and macro (transnational)—to launch ventures, exemplifying how pre-migration capital shapes post-migration outcomes. Chinese Business migrants, for instance, dominate this category, benefiting from China’s economic boom and asset inflation since 2000 (Dimitratos et al., 2016). For non-business migrants, entrepreneurship often serves as a survival strategy, particularly where welfare access is restricted (Morgan, 2020). However, comparative analyses of entrepreneurial success rates across visa classes remain scarce, obscuring policy-relevant insights.

Geographic and cultural factors further complicate these dynamics. Locational disadvantage—such as residence in underserved neighbourhoods—constrains entrepreneurial opportunities by limiting market access and network mobility (Skattebol & Redmond, 2019). Transnational entrepreneurs face additional hurdles, as their success hinges on how host societies value markers of social difference (for example, nationality, gender, or education) (Sandoz et al., 2022). Cultural assets also play a contested role: while some studies attribute ethnic entrepreneurship to cultural predispositions (Sandoz et al., 2022), others critique this as deterministic, overlooking structural barriers (Nwankwo & Gbadamosi, 2013).

Religion’s influence remains particularly debated. Some argue it fosters trust and ethnic cohesion, enhancing social capital (Parboteeah et al., 2015), while others find no significant effect (Altinay & Wang, 2011). This discrepancy may stem from methodological inconsistencies—for instance, treating religion as a monolithic variable rather than a dynamic network resource. In migrant contexts, faith-based networks often underpin economic resilience, suggesting religion’s role as a proxy for social capital warrants deeper scrutiny (Sithas & Surangi, 2021). This study advances the debate by operationalising religion as a measurable social capital indicator while accounting for spousal citizenship, dependents, and familial migration patterns—factors previously neglected.

Two major limitations persist in the literature on migrant entrepreneurship. First, the lack of heterogeneity in analysis. Most studies treat migrants as a monolithic group, overlooking critical variations in outcomes based on gender, visa type, or pre-migration capital. Second, insufficient attention to comparative pathways: The trade-offs between entrepreneurship and wage employment—or between incorporated and unincorporated business structures—are underexplored across subgroups.

This paper addresses these gaps by analysing how intersecting identities (for example, gender, visa applicant status) and contextual factors (for example, geographic disadvantage) shape entrepreneurial choices. We distinguish four heterogeneous groups defined by the intersection of gender (simplified to male and female) and visa applicant status (primary versus secondary applicant). As Section 5 reveals, these factors systematically influence outcomes across migrant groups over time, offering nuanced insights for policymakers and scholars alike.

3 CONCEPTUALISATION AND DATA

3.1 A Two-Stage Conceptual Framework

Several analytical and theoretical frameworks have been established to analyse migrant labour market outcomes. These models include family decision-making in immigration (Mincer, 1978), positive self-selection based on human capital theory (Borjas, 1987), immigration motivated by relative income (Stark & Taylor, 1991), and conscious decision about moving from the home country to another (Bodvarsson & Berg, 2013). These models reveal that the predominant force driving migration is a differential in wages and opportunities between origin and destination countries.

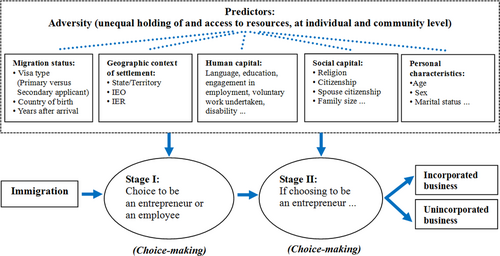

Australia’s Skilled (including Business), Family (mainly Parent and Partner), and Humanitarian visa migrants usually exhibit differing behaviour and outcomes in their new labour market. There is no unified theoretical or conceptual framework to examine thoroughly the labour market performance of diverse immigrant groups, even within a single country. The limited availability of high-quality data has restricted the general application of models. Nonetheless, factors encapsulated in existing models and the literature give a basis for us to classify potential variables collected in the microdata file to be used in this study into five domains to analyse our research questions (Figure 1).

As set out in Figure 1, the conceptual framework of this study purposefully employs the underdog entrepreneurship theory to analyse the effects of adverse experiences (versus advantages) of migrants on their labour market outcomes: 1) the choice to be an entrepreneur or an employee, and 2) the choice of a business type (incorporated versus unincorporated) for those who do choose to be entrepreneurs.

This paper therefore establishes a two-stage framework of the choice-making process at the individual level in a specific community (Figure 1). At Stage I, the cumulative impact of five clusters of factors will measure adversity or advantages for migrants at the individual and community levels. At Stage II, the choice of business ownership means migrants must further choose incorporated or unincorporated ownership.

Adversity is defined as migrant individuals’ unequal allocation of personal and community social and human capital or resources. Accessibility or adversity might be directly mediated by their migration status (for example, visa type, primary versus secondary applicant, years after arrival), individual characteristics (for example, age, sex, marital status), and geographic contexts of their settlement communities, such as State and socioeconomic conditions—which can be measured by indexes of economic resources (IERs) and indexes of education and occupation opportunities (IEOs). The IERs focus on the financial aspects of relative socioeconomic advantage and disadvantage by summarising factors related to income and housing in local settlement communities. The IEOs reflect the educational attainment and occupational level (including skill levels and employment status) of local communities. These two measures are continuous scales with a range from zero (least access to economic resources, education, and occupation opportunities) to 10 (most access). Within diverse migrant groups, those living in disadvantaged households and communities are more predisposed to have underdog status, compared to other migrants. Each domain of these factors influences entrepreneurship choice in Stage I, and subsequently the type of business ownership in Stage II. We use the proposed two-stage framework to understand how entrepreneurship choices are made and if they are directly influenced by these factors (as well as individual characteristics).

3.2 The 2021 Australian Census and Migrants Integrated Dataset (ACMID)

Our study subjected 2021 ACMID microdata—the Confidentialised Unit Record File (CURF), administered by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS)—to sophisticated statistical analysis in the ABS environment’s DataLab. This dataset covers the largest sample of migrants entering under the various Australian immigration programs. It is a valuable resource, with no sparse-data caveats, for exploring entrepreneurship in Australia’s migrant populations, at the disaggregated levels distinguished by our variables Gender and AppStatus (visa applicant status: primary versus secondary). ACMID connects 2021 Census data (ABS, 2023) with almost two million (about 90%) Permanent Migrant Database (PMD) records administered by the Department of Social Service. This linked dataset offers detailed information on the demographic, social, economic, and geographic characteristics of individual migrants. The 2021 ACMID micro-file covers only individual permanent visa holders who arrived between 1 January 2000 and 10 August 2021 (Census night), not their descendants born in Australia. Detailed information on Australian immigrants’ Permanent Residency visa classes recorded in the PMD was combined with variables including employment and enterprise ownership status on Census night 2021, enabling us to distinguish between migrants who run businesses and those who do not, and between entrepreneurs who own incorporated businesses and those who own unincorporated businesses.

4 REGRESSION METHODS

- The data can be treated as a single group, or we can recognise that they concern natural sub-groups. Preliminary examination confirms that there are significant differences in attributes between primary and secondary visa applicants and between males and females. Consequently, we analyse four sub-groups: primary applicant male; primary applicant female; secondary applicant male; secondary applicant female.

- The data within each of the four sub-groups in (1) above can be treated as a simple cross-section (pooled), or we can accept an implicit recognisable hierarchical structure; individuals at one level are nested within units at other levels. That is, there are interdependencies in the data that can be accommodated by appropriate multilevel econometric models.

- Sample selection bias occurs when data being analysed are associated with two distinct non-random groups. In our Stage I we expect that for those who are working there is a preliminary choice between being an employee and being an entrepreneur. In Stage II, the non-random group who choose to be entrepreneurs then choose either an incorporated business or an unincorporated business.

- Our two measures of outcome are binary choice variables: (i) Stage I, entrepreneur or employee; (ii) Stage II, owner of an incorporated business or unincorporated business. Consequently, non-linear models are required (Cameron & Trivedi, 2005).

In summary, we estimate eight models (four sets of pairs); Stage I is a selection model (entrepreneur versus employee) for each of the four groups. Stage II, controlling for selection bias, is the choice of incorporated or unincorporated business ownership.

4.1 Hierarchical versus pooled econometric analysis

As is well documented (see for example Rabe-Hesketh & Skrondal, 2012), ignoring a hierarchical (or nested) structure in data has significant consequences. Pooling multilevel data ignores information contained in the nesting itself; that is, there is a heterogeneous component in the groups (or nest-levels) that would be ignored. In our preliminary analysis, we examined the potential for nesting at various levels. This resulted in nesting by years in Australia (YearsAust). This is consistent with the underdog entrepreneurship theory. That is, we suggest that immigrants’ desire to become entrepreneurs develops over time; therefore, early in their time in Australia, they believe that their home country’s formal qualifications and experience will result in successful employment in Australia (that is, adequate compensation, a suitable position, using their skills and qualifications).

As is apparent from the data we examine, in many cases this expectation is not met. What migrants may experience is an inadequate reward for their skills and experience—often following some difficulty in obtaining employment. As time passes, migrants realise that their situation will not necessarily improve in the labour market. This may be for reasons that can be described as discrimination (either implicit or explicit). The longer this lasts the more disillusioned migrants become, so they seek higher returns for their skills and experience by becoming business owners. This narrative is consistent with our empirical findings.

Moreover, this outcome links directly to the underdog entrepreneurship theory. It has been recorded on numerous occasions that the Australian labour market, as with other immigrant countries (Banerjee & Lee, 2012), fails to recognise and so under-rewards skills and experience from the immigrant’s country of origin (CEDA, 2021; Green et al., 2007), which are too often not recognised as being of value (Tan & Cebulla, 2023). That is, the labour market appears to view immigrants as least likely to be a good fit in their organisation, among similarly talented non-immigrant individuals applying for positions. We can conclude that the Australian labour market classifies immigrants as underdogs. Consequently, perhaps very shortly after arrival and increasingly as time passes, immigrants choose to become entrepreneurs to compensate for inadequate employment opportunities and returns. Once that decision has been made about entering entrepreneurship, they turn to consider the relative benefits of unincorporated and incorporated businesses.

Finally and quite interestingly, our empirical exploration showed no tendency for there to be nesting by VisaType. We find this consistent with the nesting by YearsAust. Since the Australian labour market often implicitly or explicitly discriminates against immigrants, the visa type with which the immigrant gained entry is not generally the primary driver of employer decisions and hence does not result in clustering on VisaType at the aggregate level. Nonetheless, we find that both VisaType and YearsAust are generally (depending on the sub-sample) statistically significant explanatory variables and their direction of association is consistent with theory (see Section 5). Moreover, the significance of these variables with the model suggests a differentiation between group response to migrants’ visa category (that is, not nested on visa) and individual employer responses.

4.2 Sample selection bias

Sample selection bias occurs naturally in labour supply modelling (Greene, 2018). In our case, non-randomness is due to the two-stage decision process of immigrants who are working (aged 16–69). The choice to be an employee or an entrepreneur precedes the choice of owning an incorporated or unincorporated business, so the distribution of incorporated and unincorporated businesses is not independent of the choice to be an employee or an owner.

We follow Heckman’s (1979) guide to correcting for sample selection bias. In the first step, a logit model is used to estimate the probability of employment versus entrepreneurship for those who are working. Outcomes from those equations are then used to construct a correction term that is incorporated into the second-step choice equation (incorporated versus unincorporated), accounting for selection bias.

4.3 The two-step multilevel econometric model

To incorporate control for selection bias, we estimate eight models (four pairs of panel models) of the form given in equation [4] using Stata’s (v17.0) command melogit: “Multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression.”

In Stage I (selection equation [4]) estimation, we can examine the probability of immigrants choosing to be entrepreneurs or employees. Controlling for group-level heterogeneity allows examination of the factors associated with immigrants’ choices. Following Heckman (1979), we also estimate the inverse Mills ratio (IMR) based on the model’s predicted probability of being an entrepreneur. Stage II similarly estimates models of the form described in [4] for the choice between incorporated and unincorporated—including the IMR from Stage I as a control for selection at Stage II.

4.4 Analytical sample

- Self-identified either as an employee or as an owner (captured in our Entrepreneur), and if an owner, owning an incorporated or an unincorporated business (captured in our OwnStatus.)

- Age 16–69 (limited to our estimate of “usual” working age).

- Arrived in Australia between 2000 and 2021 (a data limitation).

The total analytical sample includes 1,412,981 individuals (split into eight sub-samples defined by gender and applicant status). Empirical results (see Section 5) vindicate our use of four natural sub-groups (primary applicant male, etc.). For example, we find differences between coefficients for VisaType across our four sub-samples. In some sub-samples, some explanatory variables are statistically significant; in others they are not. Results of disaggregating in four sub-samples distributed between Entrepreneur, OwnStatus, AppStatus, and Gender are shown in Table 1.

| Application status | Primary applicant | Secondary applicant | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (employee versus owner) | Female | Male | Female | Male |

| Employees | 386,704 | 432,299 | 248,200 | 168,796 |

| Column percent | 90% | 84% | 91% | 87% |

| Owner-managers: incorporated enterprises | 19,485 | 50,402 | 10,529 | 13,929 |

| Column percent | 5% | 10% | 4% | 7% |

| Owner-managers: unincorporated enterprises | 24,003 | 33,298 | 13,303 | 12,033 |

| Column percent | 6% | 6% | 5% | 6% |

| TOTAL | 430,192 | 515,999 | 272,032 | 194,758 |

| Column percent | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

- Note: Percentages may not add to 100% due to rounding.

4.5 Variable definitions and descriptions

Table 2 shows the labels we use for our variables and a brief description of each. Table 3 presents summary statistics (count, mean, standard error) for continuous variables, and Table 4 gives proportions for the categorical variables.

| Label | Description |

|---|---|

| OwnStatus | Business ownership status (employee, owner incorporated, owner unincorporated) |

| Owner | Business type if owner (incorporated versus unincorporated) |

| Entrepreneur | Owner/Entrepreneur status (entrepreneur versus employee) |

| VisaType | Visa classification and subtype |

| AppStatus | Primary or Secondary applicant (dichotomous) |

| Gender | Gender (dichotomous) |

| State | Destination state or territory |

| Aust_cit | Australian citizenship (dichotomous) |

| Sp_Aust_cit | Spouse is an Australian citizen (dichotomous) |

| Disability | Disabled household member (core activity needs assistance; dichotomous) |

| Marital | Registered marital status |

| Occup | Occupation (8 Categories, according to Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations, 2013, Version 1.3. Cat. No. 1220.0) |

| Religion | Religion |

| VoluntaryWk | Voluntary work undertaken |

| ChildCareNopay | Provide unpaid childcare |

| WkEngaged | Engagement with the labour market |

| CoBirth | Persons’ country of birth (9 categories) |

| Age & Agesq | Age of person (and Age squared) |

| YearsAust | Years in Australia |

| Eng | Proficiency in spoken English (3 categories) |

| Edu | Highest educational attainment (5 categories) |

| DepChilds | Count of dependent children in family |

| PepinFam | Number of people in family |

| IER | Index of Economic Resources (National Area) |

| IEO | Index of Education & Occupation (National Area) |

- Note: Other variables, not included in the models, were used in the preliminary and exploratory examination of data and models but are not listed here.

| Primary Female (N = 430,192) | Primary Male (N = 515,999) | Secondary Female (N = 272,032) | Secondary Male (N = 194,758) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | Std. dev. | Mean | Std. dev. | Mean | Std. dev. | Mean | Std. dev. |

| DepChilds | 1.47 | 2.14 | 1.26 | 1.48 | 1.63 | 2.14 | 1.44 | 1.95 |

| PepinFam | 2.92 | 1.24 | 3.11 | 1.30 | 3.29 | 1.26 | 3.27 | 1.34 |

| Age | 39.39 | 8.38 | 41.10 | 8.40 | 36.03 | 11.10 | 33.94 | 11.58 |

| IEO | 6.70 | 2.61 | 6.72 | 2.57 | 6.53 | 2.55 | 6.32 | 2.58 |

| IER | 5.47 | 2.89 | 5.62 | 2.92 | 5.93 | 2.91 | 5.77 | 2.92 |

| YearsAust | 11.07 | 5.07 | 11.30 | 4.98 | 11.33 | 4.79 | 11.79 | 4.77 |

| Female | Male | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | Secondary | Primary | Secondary | |

| Aust_cit | ||||

| Australian | 54.7 | 70.3 | 59.6 | 70.9 |

| Not Australian | 45.3 | 29.7 | 40.4 | 29.1 |

| Disability | ||||

| None | 99.5 | 99.5 | 99.6 | 99.5 |

| Family member disabled | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| VoluntaryWk | ||||

| Not volunteer | 88.5 | 86.4 | 89.0 | 89.7 |

| Volunteer | 11.5 | 13.6 | 11.0 | 10.3 |

| Edu | ||||

| Postgraduate/GradDip/Grad | 29.3 | 20 | 29.6 | 14.2 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 40.5 | 36.1 | 34.6 | 29.5 |

| Advanced Dip/Diploma | 11.6 | 12.2 | 12.4 | 10.5 |

| Certificates I-IV | 6.5 | 9.6 | 11.8 | 13.5 |

| Secondary education and below | 12.1 | 22.1 | 11.7 | 32.2 |

| Eng | ||||

| English only | 27.8 | 30.7 | 30 | 31.4 |

| Very well/well | 67.3 | 65.4 | 65.5 | 64.2 |

| Not well/not at all | 4.9 | 4.0 | 4.5 | 4.4 |

| State | ||||

| NSW | 32.7 | 27.8 | 32.5 | 26.6 |

| Vic | 28.7 | 27.1 | 29.7 | 28.5 |

| Qld | 16.4 | 16.8 | 14.9 | 17.1 |

| SA | 5.5 | 6.8 | 5.6 | 7.0 |

| WA | 12.1 | 17.8 | 13.5 | 16.6 |

| Tas | 1.1 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| NT | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.0 |

| ACT | 2.4 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.3 |

| Sp_Aust_cit | ||||

| Spouse_Aust citizen | 59.9 | 44.7 | 53.9 | 36.7 |

| Spouse_non-Aust citizen | 16.1 | 22.5 | 28.2 | 21.4 |

| Absent/no spouse | 24.1 | 32.8 | 17.9 | 41.9 |

| Marital | ||||

| Never married | 21.0 | 32.0 | 17.2 | 44.5 |

| Widowed | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| Divorced | 7.5 | 3.4 | 4.4 | 2.1 |

| Separated | 3.4 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 1.2 |

| Married | 67.0 | 62.5 | 75.9 | 52 |

| Occup | ||||

| Manager | 11.4 | 8.7 | 18.0 | 11.0 |

| Professionals | 38.7 | 28.8 | 35.4 | 22.3 |

| Technicians & trades workers | 4.6 | 4.5 | 17.4 | 16.2 |

| Community & personal service | 16.3 | 21.7 | 5.1 | 9.7 |

| Clerical & administrative | 14.3 | 17.0 | 6.4 | 7.9 |

| Sales workers | 5.7 | 10.2 | 3.6 | 8.9 |

| Machinery operators & drivers | 1.4 | 1.5 | 7.5 | 11.0 |

| Labourers | 7.7 | 7.7 | 6.5 | 12.9 |

| Religion | ||||

| Christian | 36 | 39.8 | 31.6 | 38.9 |

| Secular | 34 | 28.9 | 32.6 | 32.4 |

| Islam | 4.3 | 6.2 | 9.0 | 6.8 |

| Hindu | 11.0 | 15.9 | 16.5 | 11.2 |

| Jewish | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| Buddhist | 10.2 | 5.6 | 5.4 | 5.2 |

| Other religion | 4.2 | 3.2 | 4.5 | 5.1 |

| ChildCareNopay | ||||

| Not Provided | 52.4 | 58.8 | 52 | 67.9 |

| Care Own Child | 44.8 | 37.4 | 46.4 | 29.8 |

| Care Other | 2.1 | 3.3 | 1.2 | 2.0 |

| Care Own & Other | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| WkEngaged | ||||

| Fully engaged | 64.2 | 63.1 | 85.8 | 80.7 |

| Partially engaged | 31.0 | 33.4 | 12.0 | 16.9 |

| AtleasPartialEng | 4.7 | 3.5 | 2.3 | 2.4 |

| CoBirth | ||||

| India | 15 | 17.9 | 20.9 | 17.2 |

| UK | 10.2 | 15.7 | 14.7 | 15.7 |

| China | 14.1 | 8.7 | 9.2 | 9.1 |

| Philippines | 7.9 | 7.4 | 4.4 | 7.7 |

| South Africa | 2.4 | 7.4 | 3.9 | 6.9 |

| Sri Lanka | 2.0 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 2.6 |

| Malaysia | 2.9 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 2.4 |

| Other | 45.5 | 37.9 | 42.1 | 38.4 |

| VisaType | ||||

| Independent_skilled | 25.2 | 37 | 38 | 35 |

| Employer_sponsored_skilled | 14.3 | 33.3 | 24.9 | 29.2 |

| Government_sponsored_skilled | 4.2 | 13 | 7.2 | 12.9 |

| Business_skilled | 0.5 | 3.5 | 0.7 | 3.8 |

| Family Partner | 52.4 | 5.4 | 24.6 | 7.9 |

| Family Parent & Other | 2.4 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 2.3 |

| Humanitarian | 1.1 | 6.1 | 2.4 | 8.9 |

- Note: Percentages may not add to 100% due to rounding. Includes only those (initially) engaged in the labour market.

5 EMPIRICAL RESULTS

As described above, we analyse four sub-samples: primary versus secondary visa applicants, for females and males. Further, we estimate multilevel models in two stages. Table 5 presents a summary of the estimated odds ratio (OR) from the four Stage I and Stage II logistic multilevel models (where YearsAust defines the second level). While this approach proves successful in differentiating between types of immigrants and outcomes, the drawback is that we have 480 estimated coefficients, and detailing all results is impractical. Instead, following our conceptual framework, we discuss the implications of the models’ extensive set of explanatory variables by grouping them into five categories: Migration status; Geographic context of settlement; Human capital; Social capital; and Personal characteristics (Other). For each of these five, we select interesting results for discussion but give a complete summary of estimated regression coefficients (as ORs) in Table 6. As a guide to interpreting the ORs, note the coding we use for our binary dependent variables.

| Stage I | Stage II | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Employee | OR < 1 | Incorporated | OR < 1 |

| Business owner | OR > 1 | Unincorporated | OR > 1 |

| Variables | Stage I. Employee vs Entrepreneur | Stage II. Incorporated vs Unincorporated | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Primary Female | 2 Primary Male | 3 Secondary Female | 4 Secondary Male | 1 Primary Female | 2 Primary Male | 3 Secondary Female | 4 Secondary Male | |

| Migration status | ||||||||

| VisaType (Independent_skilled = Ref.) | ||||||||

| Skilled Employer_sponsored | 0.979 | 1.035*** | 0.962** | 1.020 | 0.832*** | 0.820*** | 0.904*** | 0.938* |

| Skilled Government_sponsored | 1.081*** | 1.103*** | 0.939** | 0.941** | 1.284*** | 1.102*** | 1.166*** | 1.021 |

| Skilled Business | 7.390*** | 8.757*** | 2.147*** | 1.766*** | 0.164*** | 0.278*** | 0.141*** | 0.483*** |

| Family (Partner) | 1.487*** | 1.238*** | 0.947 | 1.062* | 1.285*** | 1.305*** | 0.675*** | 1.006 |

| Family (Parent & Other) | 20.981 | 0.780*** | 0.812*** | 0.924 | 1.768*** | 1.318*** | 1.140 | 0.999 |

| Humanitarian | 0.756*** | 0.800*** | 0.542*** | 0.986 | 1.638*** | 1.125* | 1.415* | 0.779*** |

| CoBirth (India = Ref.) | ||||||||

| UK | 1.378*** | 1.053** | 1.009 | 0.999 | 1.621*** | 1.673*** | 1.478*** | 1.787*** |

| China | 2.116*** | 1.588*** | 1.567*** | 2.178*** | 0.681** | 0.860** | 0.323*** | 0.722** |

| Philippines | 0.581*** | 0.220*** | 0.366*** | 0.318*** | 1.890*** | 2.416*** | 6.497*** | 2.255*** |

| South Africa | 1.573*** | 1.018 | 1.134*** | 1.007 | 1.664*** | 1.314*** | 1.291** | 1.301*** |

| Sri Lanka | 1.184*** | 0.781*** | 0.962 | 0.976 | 1.184 | 0.881 | 0.965 | 0.831 |

| Malaysia | 1.544*** | 1.029 | 1.033 | 1.113* | 1.426*** | 1.248*** | 1.208 | 1.341** |

| Other | 1.509*** | 1.032* | 1.134*** | 1.181*** | 1.393*** | 1.376*** | 1.082 | 1.203*** |

| YearsAust (Continuous) | 1.378*** | 1.053** | 1.009 | 0.999 | 1.621*** | 1.673*** | 1.478*** | 1.787*** |

| Geographic context of settlement | ||||||||

| State (NSW = Ref.) | ||||||||

| Vic | 1.057*** | 1.149*** | 1.107*** | 1.243*** | 1.045 | 1.239*** | 1.008 | 1.241*** |

| Qld | 1.358*** | 1.359*** | 1.325*** | 1.419*** | 0.918 | 1.286*** | 0.698*** | 1.284*** |

| SA | 1.080*** | 1.231*** | 1.010 | 1.376*** | 1.157** | 1.667*** | 1.239*** | 1.756*** |

| WA | 1.119*** | 1.112*** | 1.044* | 1.210*** | 1.122** | 1.530*** | 1.135** | 1.521*** |

| Tas | 1.551*** | 1.424*** | 1.319*** | 1.371*** | 1.194 | 2.085*** | 0.883 | 1.148 |

| NT | 1.016 | 0.984 | 0.967 | 0.873 | 1.602*** | 1.722*** | 0.938 | 1.729*** |

| ACT | 0.783*** | 0.895*** | 0.724*** | 0.920 | 1.156 | 1.142* | 1.242 | 1.570*** |

| IEO (Continuous) | 1.057*** | 1.149*** | 1.107*** | 1.243*** | 1.045 | 1.239*** | 1.008 | 1.241*** |

| IER (Continuous) | 1.358*** | 1.359*** | 1.325*** | 1.419*** | 0.918 | 1.286*** | 0.698*** | 1.284*** |

| Human capital | ||||||||

| Eng (English only = Ref.) | ||||||||

| Very well/well | 1.057*** | 1.121*** | 1.185*** | 1.168*** | 0.925** | 1.022 | 0.791*** | 0.957 |

| Not well/not at all | 1.367*** | 1.120*** | 1.870*** | 1.270*** | 0.777*** | 1.106** | 0.456*** | 1.076 |

| Edu (Postgraduate/GradDip/Grad = Ref.) | ||||||||

| Bachelor degree | 1.033** | 1.165*** | 1.086*** | 1.226*** | 1.025 | 0.989 | 0.883*** | 1.104* |

| Advanced Diploma/Diploma | 1.282*** | 1.301*** | 1.367*** | 1.381*** | 0.968 | 1.035 | 0.695*** | 1.051 |

| Certificates I–IV | 1.159*** | 1.641*** | 1.205*** | 1.634*** | 1.263*** | 1.081 | 0.903 | 1.165 |

| Secondary education or below | 1.257*** | 1.289*** | 1.237*** | 1.413*** | 1.052 | 1.025 | 0.777*** | 1.122 |

| ChildCareNopay (Not provided = Ref.) | ||||||||

| Care own child | 61.14*** | 1.075*** | 1.223*** | 1.145*** | 0.990 | 1.041* | 0.847** | 1.060 |

| Care other | 1.215*** | 1.067* | 1.122*** | 0.94 | 1.001 | 1.052 | 0.785** | 1.130 |

| Care own & other | 1.236*** | 0.849*** | 1.553*** | 0.992 | 0.998 | 1.426*** | 1.025 | 0.777 |

| WkEngaged (Fully engaged = Ref.) | ||||||||

| PartialEngage | 1.481*** | 2.341*** | 1.508*** | 2.144*** | 1.789*** | 2.201*** | 1.695*** | 1.850*** |

| AtLeasPartialEng | 0.812*** | 1.238*** | 0.92 | 1.336*** | 1.409*** | 1.356*** | 1.190 | 1.358** |

| VoluntaryWk (Not volunteer = Ref.) | ||||||||

| Volunteer | 1.215*** | 1.083*** | 1.206*** | 1.129*** | 1.065 | 1.035 | 0.983 | 1.054 |

| Disability (None = Ref.) | ||||||||

| Fam Member Disab | 0.931 | 1.117* | 0.941 | 1.100 | 1.008 | 1.030 | 1.119 | 0.856 |

| Occup (manager = Ref.) | ||||||||

| Professionals | 0.406*** | 0.553*** | 0.430*** | 0.423*** | 4.388*** | 2.903*** | 10.853*** | 3.986*** |

| Technicians & trades | 0.767*** | 0.817*** | 0.590*** | 0.705*** | 4.287*** | 3.740*** | 8.834*** | 4.069*** |

| Community & personal service | 0.331*** | 0.278*** | 0.258*** | 0.165*** | 9.128*** | 6.352*** | 48.119*** | 6.891*** |

| Clerical & admin | 0.214*** | 0.347*** | 0.2012*** | 0.278*** | 1.467 | 2.617*** | 6.376*** | 2.631*** |

| Sales workers | 0.371*** | 0.590*** | 0.255*** | 0.295*** | 2.380*** | 1.897*** | 10.270*** | 2.038*** |

| Machinery operators & drivers | 0.378*** | 0.888*** | 0.440*** | 0.576*** | 11.83*** | 9.888*** | 22.822*** | 8.582*** |

| Labourers | 0.315*** | 0.601*** | 0.293*** | 0.361*** | 6.618*** | 5.182*** | 28.660*** | 5.222*** |

| Social capital | ||||||||

| Religion (Christian = Ref.) | ||||||||

| Secular | 1.287*** | 1.160*** | 1.298*** | 1.197*** | 1.012 | 1.229*** | 0.862* | 1.120** |

| Islam | 1.213*** | 1.523*** | 1.420*** | 1.710*** | 0.792*** | 0.989 | 0.439*** | 0.936 |

| Hindu | 0.999 | 1.038** | 0.876*** | 1.128*** | 0.762*** | 0.812*** | 0.801** | 0.791*** |

| Jewish | 1.701*** | 2.131*** | 1.608*** | 2.718*** | 0.890 | 1.322** | 0.831 | 1.020 |

| Buddhist | 1.343*** | 1.064*** | 1.302*** | 1.027 | 0.878* | 1.110** | 0.693*** | 1.013 |

| Other religion | 1.136*** | 2.124*** | 1.018 | 2.598*** | 0.680*** | 0.855 | 0.650*** | 0.677** |

| Aust_citizen (Australian = Ref.) | ||||||||

| Not Australian | 1.066*** | 0.993 | 1.102*** | 1.096*** | 1.169*** | 1.250*** | 0.939 | 1.081* |

| Sp_Aus_cit (Spouse_Aust citizen = Ref.) | ||||||||

| Spouse_non-Aust citizen | 0.966** | 0.982* | 0.930*** | 0.962* | 0.929** | 0.981 | 1.241*** | 1.046 |

| Absent/no spouse | 0.927*** | 0.894*** | 0.793*** | 0.750*** | 0.835*** | 0.981 | 1.479*** | 1.191** |

| DepChilds (Continuous) | 0.999 | 1.015*** | 1.028*** | 1.002 | 1.020*** | 0.978*** | 0.949*** | 0.997 |

| PepinFam (Continuous) | 1.054*** | 1.061*** | 0.999 | 1.003 | 0.882*** | 0.921*** | 0.975 | 0.957*** |

| Personal characteristics (other) | ||||||||

| Age (Continuous) | 0.999*** | 0.999*** | 0.999*** | 0.998*** | 1.000 | 1.000*** | 1.002*** | 1.001*** |

| AgeSq (Continuous) | 0.999 | 1.015*** | 1.028*** | 1.002 | 1.020*** | 0.978*** | 0.949*** | 0.997 |

| Marital (Never married = Ref.) | ||||||||

| Widowed | 0.935 | 0.908 | 0.964 | 1.167 | 0.741** | 0.848 | 1.019 | 0.248*** |

| Divorced | 1.152*** | 1.126*** | 1.056 | 1.392*** | 0.733*** | 0.845*** | 0.808** | 0.634*** |

| Separated | 1.016 | 1.047 | 1.027 | 1.388*** | 0.871* | 0.750*** | 0.693*** | 0.780* |

| Married | 1.116*** | 0.979 | 1.216*** | 1.192*** | 0.708*** | 0.829*** | 0.562*** | 0.695*** |

- Notes: *** significant at 1% level, ** significant at 5% level, * significant at 10% level. Stage II tests for Unincorporated (hence an OR<1 favours incorporation).

5.1 Migration status (VisaType, CoBirth, YearsAust)

VisaType, CoBirth, and YearsAust all play a significant role in both the choice to be an entrepreneur and of incorporation or not, for all sub-samples. We consider only statistically significant model coefficients unless otherwise stated.

For VisaType, as shown in Table 6, odds ratios (ORs) generally vary significantly in size across the eight models. Moreover, there are interesting differences between the four sub-samples. Applicant’s type of entry visa Skilled Independent is the base case in the analysis. Unsurprisingly, migrants on Skilled Business visas strongly favour entrepreneurship (see Table 6; OR 1.77 and 8.76, for secondary applicant males and primary applicant males respectively) compared to the base; and they also favour being incorporated compared to the base unincorporated (OR 0.28 and 0.48). There is a very small preference, however, for Skilled Employer-sponsored primary applicant males to choose entrepreneurship (OR 1.03), while secondary females are less likely to choose entrepreneurship (OR 0.96). Nonetheless, all employer-sponsored migrants who choose entrepreneurship have a preference for being incorporated (OR <1). Primary applicant Skilled Government-sponsored migrants are (marginally) more likely to choose entrepreneurship (OR >1) for both males and females than the base, but secondary applicants (especially females) are (marginally) less likely (OR <1).

Looking into the Partner and Parent schemes under the Family visa type, migrants entering the country holding a Partner visa are more likely to become entrepreneurs than the base and also than the Parent group. Interestingly, primary or secondary applicant status has a greater propensity for entrepreneurship. Likewise, primary applicants are more likely than secondary applicants to prefer unincorporated. Female humanitarian migrants, regardless of primary or secondary applicant status, are more likely to prefer entrepreneurship (OR >1), while male humanitarian migrants are indifferent (OR not significantly different from 1).

Overall, we find that for the significant categories, 18 of the 24 coefficients for Entrepreneur are statistically significant, with eight ORs < 1 and 10 ORs > 1. For incorporation (OwnStatus), we find four coefficients non-significant with 10 ORs < 1 favouring incorporated and seven ORs > 1 favouring unincorporated.

YearsAust (years in Australia) is associated with the choice of entrepreneurship (OR significant in all models, and >1 except secondary applicants for entrepreneurship) and with the choice to remain unincorporated (OR significant in the four models, and >1). While the impact is relatively small for primary males (OR for entrepreneurship 1.053) as the dependent variable is a continuous number of years, the cumulative influence is not minor.

CoBirth (country of birth) also plays a significant role. As shown in Table 6, of the 56 coefficients associated with this categorical variable, 41 are statistically significant. Using India as the base, migrants from China are more likely to choose entrepreneurship (OR 1.57–2.18) (Stage I) and prefer incorporated (OR 0.32–0.86) (Stage II). More generally, those from India are less likely to choose entrepreneurship (Stage I) and less likely to choose incorporated than migrants from the UK, South Africa, Malaysia, or Other (Stage II). Those from the Philippines who chose entrepreneurship are most likely to select an unincorporated business compared to those from India (OR 1.89–6.50) (Stage II). Further demonstrating across-country differences, we see that primary applicant females from Sri Lanka are more likely (OR 1.18), but primary applicant males are less likely (OR 0.78) to choose entrepreneurship (Stage I).

Generally, compared to India there are significant differences in the choice of entrepreneurship or of being incorporated versus unincorporated between countries. While sometimes choices differ by country of origin, there is overall consistency. When significant, migrants from South Africa, the UK, China, and Others, for example, tend to prefer entrepreneurship, and those from the Philippines employment; all from the UK, South Africa, and Others tend to prefer unincorporated.

5.2 Geographic context of settlement (State, IER, IEO)

When examining the influence of State (initial Australian state or territory of residence), we use New South Wales (NSW) as the base. In comparison to NSW, almost all locations are associated with entrepreneurship (ORs 1.06 to 1.55) except the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) and the Northern Territory (NT) whose preference is for Employment. Secondary female applicants in South Australia (SA) do not differ statistically from NSW. On the other hand, of the 24 significant coefficients for incorporation, only Qld secondary applicant females are less likely than NSW to choose incorporated; the rest reveal a greater tendency to be unincorporated compared to the base case (ORs 1.12–1.76).

Both the IER and IEO are strongly associated with selecting entrepreneurship in preference to being an employee: all eight coefficients are statistically significant at the 1% level (or better) with OR ranging from 1.06 to 1.442—noting that these two measures are continuous scales from zero to 10 (indicating least to most access to economic resources, education, and occupation opportunities). Similarly, except for secondary applicant females, the higher either index is, the more likely it is for the migrant to select an unincorporated business than an incorporated one (ORs 1.23–1.29).

5.3 Human capital (Eng, Edu, ChildCareNopay, WkEngaged, VoluntaryWk, Disability, Occup)

Eng (English language ability) shows a consistent pattern. Lower levels are all associated with an increased likelihood of entrepreneurship (ORs 1.06–1.87), as apparent in Table 6, Stage I. For the choice of incorporation or not, females are associated with incorporated (ORs 0.46–0.92), but only males with the lowest level prefer unincorporated business (Table 6, Stage II).

For Edu (educational attainment), compared to the base of Postgraduate (Postgraduate/GradDip/Grad), all other levels are associated with an increased probability of entrepreneurship (16 ORs statistically significant and >1: 1.03–1.64). For unincorporated versus incorporated, education does not appear to be very influential; only four coefficients are significant at the 5% level or better. Of those, secondary applicant females tend to choose incorporated, and only primary applicant males are more likely to select an unincorporated structure.

For ChildCareNopay (provision of unpaid childcare), compared to the base “not provided,” any level of provision is associated with a preference for entrepreneurship in 10 of the 12 cases—the other two are secondary males and are not significant. This is probably because females choosing entrepreneurship are more reconciled to family duties due to time constraints and balancing family–work conflicts, even if flexible part-time work or working from home could be arranged in some circumstances (Husted et al., 2001; Waxman, 2000).

Among those falling outside the categories unemployed and not in the labour force (NILF)—WkEngaged (engagement with the labour market)—those self-classified as partially engaged are more likely to choose entrepreneurship (ORs 1.48–2.34) but have a preference for unincorporated business (ORs 1.79–2.20). For those “at least partially engaged,” results are mixed. Primary applicant females are less likely to choose entrepreneurship (OR 0.81), but primary and secondary applicant males are more likely (OR 1.24 and 1.34 respectively). All groups except secondary applicant females consistently prefer unincorporated (ORs 1.36–2.20).

As for VoluntaryWk, all female applicants with volunteering work experience in Australia are significantly associated with a probability of entrepreneurship (both OR 1.14); and they prefer incorporated businesses (OR 1.12 and 1.26). Only primary applicant males have a preference between employment and entrepreneurship, and there is no association between preference for unincorporated versus incorporated for males.

Disability has almost no influence. Primary male applicants have a significant and slight positive OR (1.117) at the 10% level and show a preference for entrepreneurship. Otherwise, this variable has no impact. This result is probably driven by the very small proportion of migrants with a disability; a likely consequence of Australia’s Health Requirements for migrants.

Occup (occupation classification) is strongly influential. In comparison with the base (manager), all other occupations are less likely to choose entrepreneurship (ORs 0.16–0.89). Among the four groups who choose to become entrepreneurs, all occupations (except primary female applicants working as clerical and administrative workers) are more likely to be unincorporated (ORs 1.90–28).

5.4 Social capital (Religion, Aust_Cit, Sp_Aust_Cit, DepChilds, Pepinfam)

Social capital plays a vital role in migrants’ choices, but the diversity is such that no outstanding patterns emerge. Using Christianity as the base, however, when examining the influence of Religion, all but two categories prefer entrepreneurship—only primary applicant Hindu females and secondary applicant Buddhist males have no preference (OR: 1.0 and 1.03). Regarding the preference for incorporation, however, of the 24 ORs, only 4 are >1, 13 are <1, and 7 are not significant. On balance, the preference is for incorporation except for primary applicant males who prefer unincorporated if Secular, Jewish, or Buddhist, and secondary applicant males who prefer unincorporated if Secular.

Citizenship (Aust_citizen): non-Australian citizens tend to prefer entrepreneurship (except primary applicant males) and Unincorporated businesses (except secondary applicant females). For spousal citizenship status (Sp_Aust_cit), compared to the base case of “spouse is an Australian citizen,” there is a clear preference for employment (all categories OR <1: range 0.75 to 0.98). Primary applicant females prefer incorporated while secondary female applicants prefer Unincorporated.

The more dependent children in the household (DepChilds), the more likely entrepreneurship is for primary male applicants or secondary female applicants (OR 1.01 and 1.03), except for secondary applicant males. Thus, DepChilds is associated with incorporated–unincorporated preferences and a preference for incorporated except for primary applicant females who prefer unincorporated.

The number of people in the household for primary applicant (male or female) is associated with a greater probability of entrepreneurship (OR about 1.06). For the incorporated versus unincorporated choice, all but secondary applicant females are more likely to select incorporation (ORs 0.88–0.97).

5.5 Personal characteristics (Age, Agesq, Marital)

Age has an immaterial association with an increased preference for employment (OR ~0.99 for each group) or being incorporated (OR ~1.001). This variable is modified, however, to Agesq (age squared) for 6 of the 8 groups. Apparently, as people age, the response to age generally lessens. Although a very small impact, accumulation over the 21 years of data may see a significant influence with time in Australia.

Marital plays an uncomplicated role. Compared to the base “never married” other classifications, if statistically significant, are associated with an increased likelihood of entrepreneurship (ORs 1.12–1.39). Only widowed or separated primary applicant females and males do not differ from the base case. For the incorporated–unincorporated choice, in all cases where it matters (all but two of the 16 coefficients for this variable) any marital status over the base increases the likelihood of incorporated.

Finally, we conclude that the decision to split the migrants who are not unemployed and not NILF into the four sub-samples was meaningful. A central finding is that while there are not always stark differences in the statistically significant ORs, nor in the relative sizes of those significant ORs when considered, generally, the various groups have differing collective responses to the many explanatory variables.

6 DISCUSSION AND POLICY IMPLICATIONS

6.1 Rethinking the underdog entrepreneurship theory

What emerges from our results is the diversity of the population of migrant entrepreneurs, with both those starting a business out of necessity and those that are enticed by entrepreneurship given their extensive resources (notably human capital). Underdog entrepreneurship cuts across this binary. These findings challenge the conventional contours of underdog entrepreneurship theory, which posits that disadvantaged migrant groups engage in entrepreneurship primarily due to adversity or survivalist necessity (Miller & Le Breton-Miller, 2017). While personal socioeconomic adversity and geographic contexts of settlement communities shape pathways to business ownership, this study reveals that migrants with robust human and social capital—often embedded in advantaged communities and households—also exhibit entrepreneurship propensity. This duality underscores the limitations of framing migrant entrepreneurship through a binary “necessity-versus-opportunity” lens. Instead, structural barriers (for example, credential non-recognition) and agency (for example, leveraging skills from market gaps) intersect, creating heterogeneous trajectories.

Critically, the incorporation of businesses emerges as a strategic choice tied to human and social capital. High-skilled migrants (those coming to Australia under Skilled visa schemes), despite facing migration-related adversities, utilise their resources to establish formal ventures, aligning with human capital theory’s emphasis on skill-driven economic agency. Conversely, unincorporated enterprises often reflect constrained access to institutional networks, resonating with social capital theory’s focus on relational inequalities. Underdog entrepreneurship, thus, is not monolithic; it is mediated by migrants’ intersectional positioning within Australia’s opportunity structures.

6.2 Limitations and suggestions for future research

6.2.1 Data and causality

A major limitation has been that participants are observed on only one occasion, so we could not control for individual heterogeneity (fixed effects). Ours is, therefore, an analysis of association, not of causation (although in several cases one can reasonably infer causality, for example, Skilled employee visa holders are more likely to be employed—probably a causal relationship). After exploratory data analysis, we used a pseudo-cohort effect, clustering migrants by number of years in Australia to enable controlling for cluster-unobserved heterogeneity.

6.2.2 Focus on underdog migrants

Future study is needed to examine “factors of economic geography, government policies, environmental resources, and other contextual elements [that] may be key influences in launching and supporting entrepreneurial initiatives” (Miller & Le Breton-Miller, 2017, p. 14). While the data used in this study are comprehensive, longitudinal census and linked administrative data covering migrants’ differential access to social security (welfare), healthcare, and education/training systems could usefully identify multi-scalar and multi-dimensional adversity and causal factors, processes, and outcomes of being disadvantaged migrants in the labour market. The Person Level Integrated Data Asset (PLIDA, 2006–2024) hosted by the ABS is an example of a big longitudinal database that currently integrates with 30 datasets including the Census, migrants, and data on social security recipients (including the JobSeeker and JobKeeper payments), and data on tax return, health, education, and disability. Specialised surveys with relevant stakeholders (including migrants) could deepen quantitative studies for a more nuanced understanding of how migration history and recent adverse shocks (such as COVID-19), employment, and entrepreneurship experiences over the life course influence migrants’ entrepreneurial choices and performance in Australia. Targeted qualitative data collection could enable the analysis of mechanisms through which migrants overcome adversity. Multi-scalar (personal, community, and institutional) and multi-dimensional (social, cultural, demographic, political, geographical) data and linkages could be of great value for the design of migrant services. Future efforts should address the dynamics of Australia’s migrant entrepreneurship across the life course and cohorts, and the dynamic effects of adversity (including locational disadvantage) on migrant entrepreneurship. Further, it will be important to address sectoral disparities in migrant entrepreneurship. Migrants might be overrepresented in low-growth or low-skill industry sectors (for example, retail, hospitality) and underrepresented in high-value or highly skilled sectors (for example, hi-tech, finance, renewable energy, artificial intelligence), reflecting structural inequalities, resource access barriers, and systematic biases. Future research needs to address these gaps to unravel how sectoral segregation in the labour market perpetuates adversity and shapes the choice and outcome of migrant entrepreneurship.

6.3 Policy implications

Existing theoretical perspectives and policies usually address the positive effects of human and social capital endowments on migrant entrepreneurship. Australia’s Entrepreneurs’ Program and the Entrepreneur Stream visas also target migrant entrepreneurs with high levels of human, social, and financial capital. These conventional migration theories (mainly in economics) and operational practices overlook adverse conditions that drive some migrants to engage in entrepreneurship in the labour market (possibly as a last resort). Challenges faced by migrant entrepreneurs range from navigating a new business landscape, identifying new business opportunities (Schmitt et al., 2018), and accessing new technologies to building new social capital and networks, as business knowledge is most obtained “through social interactions and socialisation” (Thornton et al., 2012:97) and through “a complex network of networks, deployed at ethnic, social, professional and educational level, both nationally and transnationally” (Gurău et al., 2020:711–712).

Fostering entrepreneurship among disadvantaged migrant populations has been practised as a national and regional development policy in the UK, the US, and Canada (Morgan, 2020; Smith et al., 2019). It is imperative for Australia to catch up with other countries in this regard. As one of the world’s major immigration countries, Australia’s demand for migrants and their skills will continue growing—to rehabilitate its economy following COVID-19. Employment is strong; unemployment is the lowest in over 40 years (ABS, 2022). The Australian and State governments must build a culture that nurtures entrepreneurship, like other developed countries competing for skilled and entrepreneurial migrants. The current minimum wage is generally indicative of the challenges in attracting them; certain skilled visa applicants are offered less than that earned by 80% of full-time employees in Australia (New Daily, 2022).

It is in Australia’s interest, both public and private, for all categories of immigrants (especially those who are disadvantaged) to settle successfully, economically and socially. Identifying enablers and barriers to successful entrepreneurship (particularly for “underdogs”) at individual, familial, community, and institutional levels will be beneficial for improved allocation of resources in programs that yield optimal outcomes, enhanced labour-market and social participation, inclusion, and cohesion. An increased understanding of such factors, especially those measuring the types of adversities across diverse groups, will help policymakers at all government levels integrate migration, foster entrepreneurship, and refine social policies.

7 CONCLUSIONS

Researchers and policymakers have a limited understanding of how diverse immigrant groups in Australia seek entrepreneurship or employment and of incorporated versus unincorporated choices among migrant entrepreneurs. Based on the 2021 ACMID microdata, this study has examined the relevance of the underdog entrepreneurship theory (in conjunction with conventional migration and entrepreneurship theories) in relation to choices among migrants entering Australia under different visa schemes over the 21 years from 2000. Migrants have varied demographic and socioeconomic characteristics and live in different geographic locations that are uneven in their social and economic affordances, which differentially cultivate or impede entrepreneurship. One of our central findings is that some migrants facing particular challenges chose to be entrepreneurs. Specifically, those with lower educational attainment or English proficiency and those doing unpaid childcare are more likely to become entrepreneurs. Humanitarian visa females (regardless of primary or secondary application status), Family (Parent and other) visa primary males and secondary application females, and Skilled Government-sponsored secondary female applicants are less likely to choose to be entrepreneurs. In contrast, Family (Partner) migrants (excluding secondary application females), Government-sponsored Skilled visa migrants (both primary females and females) are more likely to become entrepreneurs. More generally, gender and applicant status play differentiating roles between entrepreneurship and employment, and also in choices regarding incorporation. These outcomes are not always consistent with the underdog theory; they do, however, demonstrate that the issue is complex—differing results for the four sub-groups in terms of statistical and practical significance of explanatory variables in the eight models.

Migrants whom we would not classify as underdogs with relatively high levels of human capital, who engage in the labour market and reside in advantageous communities exhibit a greater tendency to become entrepreneurs. Business migrants naturally have the highest probability; they also have a stronger preference for incorporated businesses. Geographic contexts had a complex influence on entrepreneurship, posing significant discrepancies in facilitating migrants to found businesses. The richer the endowment of economic, education, and occupation resources in migrants’ settlement communities, the higher the probability of migrants engaging in entrepreneurship and for choosing unincorporated businesses. These significant associations are mediated by gender and visa applicant status (primary versus secondary). Those coming from the UK (both primary females and males) or South Africa (both primary and secondary females) might have less underdog status than those coming from Sri Lanka (primary visa males) or the Philippines. However, Britons and South Africans are more likely to become entrepreneurs than Sri Lankans and Filipinos, coming from a less developed environment. The longer migrants live in Australia, the greater their propensity toward both entrepreneurship and un-incorporation. We find mixed results for religious background. Statistical and practical significance is strong; robust results provide empirical insight into the role of religion.

We therefore conclude that these findings partially confirm and extend the underdog entrepreneurship theory (Miller & Le Breton-Miller, 2017). They challenge the underdog theory by revealing that structural barriers and resource access, rather than pure disadvantage, shape migrant entrepreneurial pathways. While human capital theory explains resource-rich migrants leveraging skills for opportunity-driven ventures, those facing adversity (despite moderate capital) navigate constraints through unincorporated enterprises, underscoring social capital’s limited compensatory power. However, underdog entrepreneurship transcends the necessity-opportunity binary, emerging intersectionally where systemic exclusion meets aspirational resilience, even among ostensibly advantaged migrant groups. This suggests theories must integrate structural contexts—geographic, demographic, and institutional—to account for how migrants mobilise heterogeneous resources amid adversity, complicating deterministic human/social capital frameworks and rethinking underdog entrepreneurship as negotiated within layered inequalities. Our results are useful evidence for entrepreneurship policymaking and migrant service design. Longitudinal studies that address the dynamics of Australia’s migrant entrepreneurship across the life course and cohorts and research that addresses sectoral disparities in migrant entrepreneurship are some interesting future research directions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by the Australian Research Council (DP170101726). We are grateful to the anonymous Associate Editor and two anonymous reviewers for providing constructive comments on the early manuscript. Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Adelaide, as part of the Wiley - The University of Adelaide agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

There is no research ethics issue.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

This study utilised microdata from the 2021 Australian Census and Migrants Integrated Dataset (ACMID), specifically the Confidentialised Unit Record File (CURF; ABS Cat. No. 3417.0.55.001, 2021). All analyses were conducted in the secure Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) DataLab environment. Access to these detailed microdata required formal ABS approval, which we gratefully acknowledge.