Criminal mutilation in Sweden from 1991 to 2017

Funding information

This study was supported in part by the Swedish National Board of Forensic Medicine

Abstract

We identified 43 cases of mutilation homicides in a nationwide population-based study in Sweden during the period of 1991–2017. 70% of cases were classified as defensive mutilations where the main motive was disposal of the body, while 30% were classified as offensive, that is, due to an expression of strong aggression, necro-/sexual sadism, or psychiatric illness. In comparison with a previous study covering mutilation homicides in Sweden between 1961 and 1990, we noted an increase in incidence. The percentage of cases involving mutilation had increased from 0.5% of all homicides in the 1960s to 2.4% in the 2010s. The most common cause of death was sharp force, but in 28% of the cases, the cause of death could not be determined. The clearance rate in cases of mutilation homicide was 67%, and in a large majority of the cases, the offender was known to the victim. With regards to gender women made up 44% of the victims, whilst men constituted 56% of the victims and a total of 95% of the offenders. Half of the offenders had a personality disorder, however, only 13% were sentenced to forensic psychiatric care.

Highlights

- This is a national population-based study of 43 cases of criminal mutilation in Sweden 1991–2017.

- Mutilation cases have increased from 0.5% of all homicides in the 1960s to 2.4% in the 2010s.

- The victims consisted of 56% males and the known offenders of 95% males.

- Common victim-offender relationships were acquaintances (33%) and intimate partners (30%).

- Of the known offenders 13% were sentenced to forensic psychiatric care and 87% to prison.

1 INTRODUCTION

Homicides involving mutilation or dismemberment of the body tend to instigate strong reactions and media attention, due to their vile nature. The phenomenon has existed for a long period of time and has been studied in forensic journals as far back as 1918 [1]. According to Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary [2], mutilation is defined as “the act of depriving an individual of a limb, member or another important part of the body; or deprival of an organ; or severe disfigurement”. There are varying motives behind mutilations, primarily to discard the body and/or aggravate identification, whereas others are performed to humiliate the victim, to carry out sexual acts, or as an expression of strong aggression or mental illness [1, 3, 4].

A number of case reports concerning mutilations have been published in the past; however, there is a lack of population-based studies covering mutilations over a longer period of time. One exception is the study by Rajs et al. [3] that identified a total of 22 deaths with criminal mutilation in Sweden during the 30-year period of 1961–1990. Two further studies, one in Finland and one in South Korea, looked into 13 cases 1995–2004 [4] and 65 cases in 1995–2011 [5], respectively. Moreover, comparisons between studies are hampered by variations in study design. Some studies have for instance only covered cities or regions in a country whilst not controlling for the total number of homicides or inhabitants in said region. Nonetheless, Adams et al. [6] reported 55 dismemberment cases in New York/USA between 1996 and 2017, Konopka et al. [7] reported 23 mutilation cases in Cracow/Poland from 1968 to 2005 and Wilke-Schalhorst et al. [8] reported 51 cases in Hamburg/Germany for the period between 1959 and 2016.

Sweden, in contrast to most other countries, has one public authority (the National Board of Forensic Medicine) covering the whole country, with digital records dating back to 1991, giving access to detailed, nationwide, medico-legal autopsy data.

Research on dismemberment and mutilation cases is scarce, especially when combined with information on criminogenic and psychosocial factors regarding the perpetrator [9]. The overarching aim of our study is to follow-up on the study performed by Rajs et al. and to investigate the prevalence and characteristics of criminal mutilations in Sweden between 1991 and 2017.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Case selection

This is a retrospective, population-based case series of all detected cases of mutilated bodies in Sweden with date of death between January 1, 1991 and December 31, 2017. Since there is no ICD-code for mutilations or dismemberment in the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of diseases, cases could not be identified by searches in the Cause of Death registry. Instead, we identified cases by free text searches in the Forensic Medicine Database [10] using words “dismembered”, “mutilated”, “decapitated”, “chopped off”, “cut off”, “sawed-off”, “separated”, “body pieces”, “body parts” “skeleton parts”, etc. In addition, cases were identified by interviewing experienced forensic pathologists and police investigators, as well as by online media searches using the above-mentioned search terms. The data were collected from autopsy reports, police investigations, and, when available, court verdicts.

Forensic psychiatric evaluations from the Forensic Psychiatric Unit at the National Board of Forensic Medicine were retrieved for offenders who had undergone such evaluations. During the pretrial process perpetrators with any risk of suffering from symptoms of mental illness undergo mandatory forensic psychiatric evaluation. These inpatient assessments last on average about four weeks and are based on observations, extensive interviews, and retrospective records. Moreover, they are conducted at the request of the court in order to assess whether the offender, from a legal aspect, suffered from a severe mental disorder when committing the offense. Severe mental disorder is a judicial term in Sweden which includes (1) all psychotic states regardless of origin, (2) severe depression with suicidal ideation, (3) personality disorders with psychotic episodes, (4) mental disorders with marked compulsiveness with an impact on the social functioning, and (5) severe mental retardation, severe dementia and severe brain damage. The final assessment results in a recommendation to the court with regards to either forensic psychiatric care or imprisonment for the perpetrator.

All other (non-mutilation) homicides in Sweden during the same study period were collected for comparison. This included all cases in which the manner of death was classified as a homicide in the Forensic Medicine Database and data regarding the victim's sex, age, and cause of death was retrieved.

2.2 Definition and classification

A restriction in previous research is the inconsistency in definitions and classifications of mutilation and dismemberment, which to some extent impedes comparisons between studies [9]. Nonetheless, the term mutilation in the present study is in accordance with the definition given in Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary [2]: “The act of depriving an individual of a limb, member or other important part of the body, deprival of an organ or severe disfigurement” This includes the term “dismemberment” which according to the same source is defined as “amputation of a limb or portion of it”. Cases with deprival of one finger or ear have not been included, but one case with deprival of two fingers, of which one is still missing, has been included in this study. Only cases where the mutilation is a result of damage being directly executed by another person have been included.

- Type I, defensive—where the motive is to get rid of the body and/or make identification more difficult and hinder or delay the police investigation.

- Type II, aggressive—where the act of killing is brought about by a state of outrage and is followed by mutilation of the body, which may involve the face or the genital organs.

- Type III, offensive—motivated by (a) a necrophilia urge to kill and carry out sexual activities with a dead body, with prior or subsequent mutilation; or (b) a sexual sadistic need to carry out sexual activities or intercourse while inflicting pain or injury; or killing, where the mutilation may be initiated in a living person and continued after the killing; or may commence after the killing.

- Type IV, necromanic—sometimes seen in regular necrophilia, as defined above, or with the purpose of using body parts as a trophy, symbol, or fetish.

In this study, the cases were divided into two main groups: defensive and offensive, due to a lack of consensus in how to classify mutilations beyond this main separator. Furthermore, the exact motive for mutilation in many cases within the offensive group is not obvious. All mutilations that were not classified as defensive were classified as offensive by default. All cases deemed non-defensive by Rajs et al. [3] were re-classified as offensive for comparative purposes in our study.

- Defensive—to discard of the body and/or obstruct identification and thus delay or hinder the police investigation.

- Offensive—all non-defensive cases, often to humiliate the victim, to perform sexual acts or as an expression of strong aggression or psychiatric illness.

Cases that expressed a mixture of motives for mutilation were classified according to the most prominent motive, for example, cases where the body had been dismembered into several parts, including the genitalia, have thus been classified as defensive since obstruction of discovery has been regarded as the dominating motive. The same argument has been applied to cases that consisted of skeletal parts, which have been classified as defensive.

2.3 Ethics

Ethical approval was obtained from the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (reference number 2018/5:1).

3 RESULTS

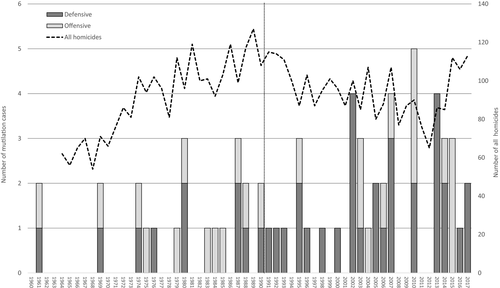

During the period of 1991–2017, a total of 43 cases of criminal mutilation were identified in Sweden. Of these, 30 cases were classified as defensive (70%) and 13 as offensive (30%). Concerning the pattern over time, the number of defensive cases had increased from 10 cases in 1960–1990, as reported by Rajs et al., to 30 cases during1991–2017. The offensive cases had remained more or less the same, 12 and 13 cases, respectively (Figure 1). The percentage of all homicides that consist of mutilation homicides increased in the later study period, from 1.0% of all homicides during the 1990s to 2.4% during the 2010s (Table 1).

| 1970s | 0.5% |

| 1980s | 1.1% |

| 1990s | 1.0% |

| 2000s | 1.8% |

| 2010s | 2.4% |

The incidence of criminal mutilation per year and million inhabitants as reported by Rajs et al. increased over the decades, from under 0.05 in the 1960s to 0.10 in the 1970s and 0.13 in the 1980s. In this study, the incidence was 0.10 in the 1990s, 0.19 in the 2000s, and 0.23 in the 2010s (Figure 2).

The age of the victims ranged from 16 to 81 years (men 16–81, women 18–76 years) with a median age of 45 years for men and 41 years for women. 56% of the victims were male and 44% were female. Meanwhile, the gender distribution in the comparison group (non-mutilation homicides) was 68% male and 32% female for the same study period. A Pearson chi-square test did not show a statistically significant difference in gender distribution between the two study groups (p = 0.11). 47% of the cases (n = 20) were found in the Stockholm area (crime scene or scene of disposal). In cases where material for forensic toxicology analysis could be obtained from the autopsy, screening for alcohols and drugs was performed. In 14 cases (33%), alcohol was detected (BAC 0.026–0.31%) and in six cases (14%) narcotic substances were detected (opioids, benzodiazepines, and central stimulants).

3.1 Cause and manner of death

The causes of death for mutilation victims compared to other victims of homicide can be found in Table 2. The most common cause of death was due to sharp force: 35% of defensive mutilations and 62% of offensive mutilations, compared with 42% of other homicide victims. Death by firearms was less common in the mutilation group (9% of defensive and 0% in offensive mutilations) compared to 23% in non-mutilation homicides. Sharp force trauma and blunt force trauma were the only causes of death in the offensive mutilation group. In twelve of the 43 mutilation cases (28%), no cause of death could be determined, and all of these cases were classified as defensive mutilations. In comparison, according to a search in the Forensic Medicine Database, the cause of death could not be determined in 4% for all other cases that underwent medico-legal autopsy in Sweden during the same study period. Cause of death could be determined in all cases of offensive mutilation. The reasons cause of death could not be established in defensive mutilations was due to decomposition/skeletonization of the body/body parts, the absence of crucial body parts, or simply damage to the body parts by the mutilation itself.

| Dismemberment (n = 43) | Non dismemberment (n = 2508) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Defensive (n = 30) | Offensive (n = 13) | ||

| Cause of death | |||

| Sharp force | 15 (35%) | 8 (62%) | 42% |

| Firearm | 4 (9%) | 0 (0%) | 23% |

| Blunt force | 9 (21%) | 5 (38%) | 20% |

| Strangulation | 3 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 10% |

| Other | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 4% |

| Unknown | 12 (28%) | 0 (0)% | 0% |

| Manner of death | |||

| Homicide | 24 (80%) | 13 (100%) | |

| Undetermined | 6 (20%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 17 (57%) | 7 (54%) | 68% |

| Female | 13 (43%) | 6 (46%) | 32% |

| Age | 42 ± 17 | 42 ± 15 | 40 ± 19 |

In six of the 30 defensive dismemberment cases, manner of death was determined as unclear; none of these had a determined cause of death. Nonetheless, in six other cases, manner of death was established as homicide, despite an undetermined cause of death. In the entire offensive dismemberment group, the cause of death could be determined and the manner of death was homicides in all cases.

3.2 Mode of mutilation

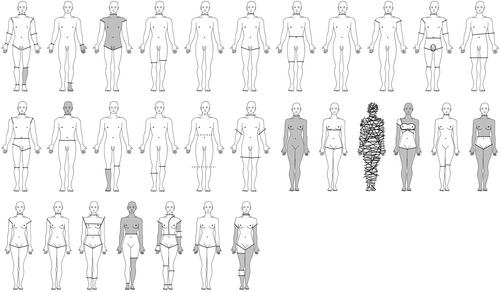

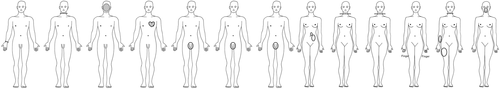

The detailed characteristics of mutilation victims can be found in Table 3. The most common mode of mutilation was to divide the body into four or five parts (in cases where all body parts have been found). In a third of cases, one or several body parts are still missing (n = 15). The most common body part that had been removed was the head (n = 25). In three cases, the victim's penis was found in the victim's mouth. In Figures 3 and 4 schematic presentations of the modes of mutilation can be found, divided according to defensive/offensive manner as well as victim sex. The most common tool for mutilation in the defensive group was a saw (n = 10) while a knife was used in the offensive group (n = 8). It was common for body parts to have been removed from the scene of death in the defensive group; in only five (17%) of the defensive cases, all body parts were found at the same place, the supposed scene of death. In the offensive group, all body parts were found at the scene of death in all ten solved cases (Tables 4 and 5).

| Defensive | Offensive | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 30 | n = 13 | n = 43 | |

| Unsolved cases | 11 | 3 | 14 |

| Body found | |||

| At the scene of death (all body parts) | 5 | 10 | 15 |

| At multiple places, partly at the scene of death | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| No body parts at scene of death | 13 | 0 | 13 |

| Scene of death unknown | 8 | 3 | 11 |

| Dismemberment tool | |||

| Saw | 10 | 1 | 11 |

| Knife | 5 | 8 | 13 |

| Spade or scissors | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Multiple | 9 | 2 | 11 |

| Unknown | 5 | 1 | 6 |

| Body parts in average | 4–5 | 2 | |

| Decapitation | 21 | 4 | 25 |

| Penis in mouth | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Number of cases with missing body parts | 12 | 3 | 15 |

| Variable |

N (%) 40 (100%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 38 (95%) |

| Female | 2 (5%) |

| Age group | |

| 15–24 years | 12 (30.0) |

| 25–34 years | 10 (25.0) |

| 35–44 years | 7 (17.5) |

| 45–54 years | 7 (17.5) |

| 55–64 years | 3 (7.5) |

| 65+ | 1 (2.5) |

| Region of birth | |

| Sweden | 30 (75.0) |

| Other European countries | 7 (17.5) |

| Non-European country | 3 (7.5) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 19 (47.5) |

| Cohabitant/married | 13 (32.5) |

| Live-apart partner | 4 (10.0) |

| Unknown | 4 (10.0) |

| Previous criminalitya | |

| Any convictions | 24 (60.0) |

| Violent crime | 16 (40.0) |

| Unknown | 3 (7.5) |

| Relationship to victim | |

| Partner | 12 (30.0) |

| Relative | 3 (7.5) |

| Acquaintance | 13 (32.5) |

| Criminally related | 5 (12.5) |

| Stranger | 7 (17.5) |

| Influence of substances | |

| No | 11 (27.5) |

| Yes | 19 (47.5) |

| Unknown | 10 (25.0) |

- a Can add up to more than 100%.

| Variable |

N (%) 38 (100) |

|---|---|

| Mental disorders | |

| Psychotic disorder | 3 (7.9) |

| Personality disorder | 19 (50) |

| Substance use disorder | |

| No | 16 (42.1) |

| Yes | 19 (50.0) |

| Unknown | 3 (7.9) |

| Severe mental disorder | |

| No | 33 (86.8) |

| Yes | 5 (13.2) |

| Classification of crime | |

| Murder and crime against the peace of the tomb | 11 (28.9) |

| Murder | 17 (44.7) |

| Crime against the peace of the tomb | 10 (26.3) |

| Sentencing | |

| Life imprisonment | 8 (21.1) |

| Prison sentence | 25 (65.8) |

| Forensic psychiatric care | 5 (13.2) |

- a Two offenders excluded due to committing suicide after the offense and prior to sentencing.

3.3 Legal aspects

Of the 43 cases of mutilation, 67% were solved, that is, one or several perpetrators were convicted for homicide (n = 29), whereas 14 cases (33%) are still unsolved. The clearance rate was higher in the group of cases with a known cause of death. In the cases with an unknown cause of death, 33% were solved (4 out of 12), whereas 81% of the cases with a known cause of death were solved (25 out of 31). The clearance rate was higher in the offensive mutilation group (77%) than in the defensive group (63%). In three cases, no one has been convicted for the homicide (7%); however, one or several perpetrators have been convicted for the mutilation (these cases are counted as unsolved). In two of those three cases, the cause of death could not be determined due to putrefaction and/or the mutilation itself. The third case has appeared in court three times, once with a homicide conviction, but this was appealed and all perpetrators were eventually only convicted for the mutilation.

3.4 Offender characteristics

There were in total 40 offenders (95% male) with a mean age of 35 years (SD =13.98, range 18–83) in the 29 solved cases. Sixty percent of the homicide incidents involved a single offender (n = 24), whereas 33% of the incidents involved three or more offenders. With regards to the region of birth, the majority of the offenders (n = 30, 75%) were born in Sweden, followed by other European countries (n = 7, 18%). In terms of criminal history, 60% of the offenders had been convicted of a crime prior to the incident (n = 24), in which 40% had been convicted of violent crime (n = 16). The most common victim-offender relationship was acquaintances (n = 13, 33%) followed by intimate partners (n = 12, 30%). Among the twelve offenders who killed and dismembered a current or previous intimate partner, four had previously been convicted of at least one partner-related crime. With regard to being under the influence of substances in commission of the offense, nearly half (n = 19, 48%) of all offenders were under the influence of alcohol and/or drugs. More specifically, 25% of the offenders were under the influence of alcohol (n = 10) and 23% were under the influence of illicit drugs (n = 9), with or without alcohol intoxication. However, as information is missing for ten of the offenders, the figures are restrictive.

Psychiatric characteristics based on forensic psychiatric evaluations found that 8% (n = 3) suffered from a psychotic disorder in commission of the crime. The information on the frequency of personality disorders is less reliable, since individuals without indications of severe mental disorders (e.g., psychotic disorders) may not be subjected to comprehensive forensic psychiatric evaluations and thus remain undiagnosed. Nonetheless, our results demonstrate that at least 50% of the offenders had a personality disorder (n = 19). Antisocial personality disorder was predominant (n = 9, 24%), as were personality traits of narcissism and psychopathy. From a medico-legal aspect, five persons were assessed as suffering from a severe mental disorder in connection to the offense (13%), and in corroboration with this finding, the same number of offenders was sentenced to forensic psychiatric care.

4 DISCUSSION

The objective of the study was to investigate the prevalence and characteristics of criminal mutilations in Sweden between 1991 and 2017 and to compare the results with the findings by Rajs et al. [3] from the 1960s onwards. The main finding was that there has been an increase in defensive mutilations over the study period. Adding information from the Rajs et al., the studies together elucidate that offensive mutilations have been stable over time, while the defensive cases have increased, in raw numbers, per 100.000 inhabitants as well as per fraction of all homicides. The proportion of homicides with mutilation has increased from 0.5% in the 1960s to 2.4% in the 2010s and in absolute numbers, the defensive cases have increased from ten cases in the previous study period (30 years) to 30 cases in the current study period (27 years). This finding suggests that the share of all homicides, but also the incidence of mutilation homicides, both fluctuate over time. Furthermore, almost half of the defensive dismemberments in our study were located in the Stockholm area. In comparison, only about a third of the total number of homicides in Sweden took place in the Stockholm area. The increasing trend of defensive mutilation homicides can possibly be explained by the urbanization process with more people living in small areas [12], thus a possible need for dismemberment in order to dispose of a body. Hypothetically, the increase may also have been affected by an increasing availability of information on the internet and an increased production of various crime-inspired books, movies and TV series, which may contribute to inspiration and education. In one of the cases, one perpetrator admitted to having been influenced by a TV series with a serial killer as the main character. However, the impact of these hypothetical explanations could not be ascertained by the data of the present study. The number of offensive cases, on the other hand, has remained more or less the same, 12 cases in the previous study period and 13 cases in the current.

4.1 Comparison to other international studies

Published studies on mutilation from other countries are sparse. In addition, comparisons to other studies are often hampered due to different methodologies. Nonetheless, two population-based studies have been published: one by Häkkänen-Nyholm et al. [4] in Finland and one by Sea and Beauregard [5] in Korea. However, the former only includes cases that involve convicted perpetrators, while the latter has applied a wider definition of mutilation (involving arson, insertion of foreign objects, and pouring acidic liquids on the body). Moreover, these studies have not accounted for the number of inhabitants in the region when reporting absolute numbers of mutilation cases, rendering difficulties in comparing their findings with the results in our study. Another study, by Adams et al. [6], included only cases with separation of bones and excluded cases with mutilation of noses, breasts, or genitalia, which is considered to be a main feature of offensive mutilations. They compared their number of dismemberments to the average homicide rate and concluded that dismemberment occurs in one in every 224 homicides, which corresponds to 0.4% a lower figure than we found in our study. They found an average of 2.5 dismembered decedents per year over a 22-year period.

With regards to trends over time, the findings are somewhat inconclusive. Both our study and the study by Wilke-Schalhorst et al. [8] show an increase in mutilation homicides in Hamburg from 1959 to 2016, while the study by Adams et al. [6] does not. In agreement with the findings by Häkkänen-Nyholm et al. and Konopka et al., our findings suggest that the majority of mutilation homicides in Sweden are defensive in nature.

In line with the hypothetical urbanization process mentioned above, Adams et al. [6] theorized that high population density and difficulties in discarding the dead body in an urban setting were the reason why New York City experiences a higher number of dismemberment cases in comparison with other published results. In the present study, we found on average 1.6 cases per year in Sweden, and 1.2 when including dismemberment through bone only, this is in keeping with the New York study by Adams et al. Notably New York City and Sweden have a similar population size (8.3 and 10.2 million in 2019, respectively). The finding that almost half of the defensive dismemberments in our study were located in the Stockholm area is in line with the findings by Adams et al. [6], showing a higher incidence in urban settings.

Mutilation homicides have often been associated with sexual motives and Rajs et al. [3] changed the very definition of offensive mutilations to be motivated by an urge to carry out sexual activities during or after the killing. While they identified seven cases characterized by sexual motives, none of the cases in our study from 1991 involved sexual elements. In the three cases where the penis was severed and placed in the victim's mouth, there was no known sexual relationship between the victim and the offender. Instead, the motives for these actions seem to have been to humiliate the victim, rather than a sexual urge. Two case reports about postmortem penis amputations have been published [13, 14]. Apart from one case, where the victim's testicles were placed in the victim's mouth, no other cases where the penis was placed in the victim's mouth have been published. Occasional cases of homicides with subsequent penis amputation and placement in the mouth have been reported in international media. The phenomenon is thus not unheard of, it simply has not been scientifically studied.

4.2 Cause and manner of death and forensic toxicology analyses

Failure in determining the cause of death in mutilation cases was ten times more common (28%) in comparison to other medico-legal autopsy cases (4%). The inability to determine cause of death is a direct consequence of either the mutilation itself, lack of body parts, or due to decomposition after body parts have been found at a later stage. In half of the cases with an unknown cause of death, the manner of death was still determined as homicide, indicating that the manner of death was concluded from probabilistic reasoning related to circumstances. Such a strategy might be explained by the fact that determination of manner of death is a task for the forensic pathologist in the Swedish setting. This practice may make the distinction between a pure medical decision and a decision of legal character less clear than in countries where the task of the forensic pathologist is solely to determine the cause of death. In the remaining six cases, manner of death could not be determined due to missing body parts and/or severe decomposition or skeletonization.

A study that investigated the presence of alcohol and drugs in Swedish homicide victims in 2007–2009 [15] showed that 34% of the victims were under the influence of alcohol and 12% under the influence of drugs at the time of death. The results are almost identical with those in the current study, where alcohol was found in 33% of the victims and narcotic substances were detected in 14%.

4.3 Legal and psychiatric aspects

The extent to which the offenders, from a legal aspect, were assessed to suffer from severe mental disorder, and thus subsequently sentenced to forensic psychiatric care, did not differ from other studies examining homicide in a Swedish context [16]. As such, a minority, 13%, of the convicted offenders were sentenced to forensic psychiatric care. This is in stark contrast to the study by Rajs et al. [3] in which the majority of the offenders, 75%, were sentenced to forensic psychiatric care. This difference is rather due to shifts over time concerning legislation and definitions as to what constitutes severe mental disorder. These shifts have led to changes in the population sentenced to forensic psychiatric care [17], thus the results with regards to sentencing and severe mental disorder in our study are not comparable to that of the previous study by Rajs et al.

The clearance rate of all homicides in Sweden varied during the study period between 68% and 90% with a mean of 80% [18]. The clearance rate for the defensive dismemberment cases was 63% compared to the offensive group that had a higher clearance rate of 77%. Compared to some years, the clearance rate of mutilation homicides in total, 67%, and especially defensive dismemberments (63%), was fairly low compared to other homicides, which can be explained by unknown cause and manner of death, poor technical evidence, etc. This could indicate that the perpetrators’ attempt to hamper the legal investigation was in some cases successful. In three cases, involving ten offenders, the offenders were only convicted for the mutilation itself and not for the homicide. In these cases, the police investigation had not been able to rule out suicide or accident as a manner of death, as claimed by the offenders. In Sweden, postmortem mutilation is a crime called “violation of the peace of the tomb”, with a punishment ranging from a fine to a maximum of two-year imprisonment.

5 CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, this population-based study shows that there has been an increase in defensive mutilations in Sweden but no increase in offensive mutilations since the 1960s. Even though there is some difficulty in comparing results between studies due to different methodology, the results at large corroborate other reported international findings on mutilation homicides. Hence, the study lends support to previous findings showing that mutilation homicides are predominantly defensive in nature, and more often occur in densely populated areas.