Show Your Hand: The Impacts of Fair Pricing Requirements in Procurement Contracting

ABSTRACT

This paper studies how a federal procurement regulation, known as the Truth in Negotiations Act (TINA), affects the competitiveness and execution of government contracts. TINA stipulates how contracting officials (COs) can ensure reasonable prices. Following TINA, for contracts above a certain size threshold, COs can no longer rely solely on their own judgment that a price is reasonable. Instead, they must either require suppliers to provide accounting data supporting their proposed prices or expect multiple bids. Using a regression discontinuity design, I find that above-threshold contracts experience greater competition (i.e., more bids), improved performance (i.e., less frequent renegotiations and cost overruns), and reduced use of the harder-to-monitor cost-plus pricing, compared to below-threshold contracts. These findings suggest that TINA's requirements enhance competition and oversight for above-threshold contracts.

1 Introduction

In 2018 alone, governments around the world spent $13 trillion on the procurement of goods and services, equivalent to 15% of global GDP (OCP [2020], World Bank [2020]). A major challenge that governments face is ensuring fair pricing, a concern underscored recently by the U.S. Senate and the media (Sanders et al. [2023], Whitaker [2023]). To address this concern, governments generally require their contracting officials (COs) to ensure that a price is reasonable in at least one of three ways: (1) by using their own judgment based on their analyses of prices, (2) by requiring suppliers to privately disclose accounting information supporting their proposed prices, and (3) by relying on competition among multiple independent bidders. These approaches for establishing reasonable prices can protect governments by lessening information asymmetry and strengthening their bargaining power. For higher value contracts, governments often restrict COs from relying solely on their own judgment of reasonable prices to mitigate errors, shirking, and collusion with bidders (Jensen and Meckling [1976]). Despite the importance of price reasonableness policies, there is limited evidence on how they shape procurement outcomes (Bosio, Djankov, Glaeser, and Shleifer [2020]).

To address these issues, I examine a U.S. federal procurement regulation known as the Truth in Negotiations Act (TINA), which affects the methods COs can use to establish price reasonableness. TINA stipulates that COs must require suppliers to disclose comprehensive accounting data to the government for contracts that exceed a certain price (i.e., the “TINA threshold”) if the government does not expect to receive multiple bids.1 TINA's requirements imply that COs may use either competition or accounting data to ensure that prices are reasonable for contracts above the threshold; COs can no longer rely solely on their own judgment. I study the effects of TINA on competition (i.e., number of bids), contract performance (i.e., frequency of renegotiations and budget overruns), and reliance on harder-to-monitor cost-plus contracts rather than fixed price contracts. These outcomes matter because they relate to public spending, the fairness of the procurement process, supply chain risk, and the quality of goods and services (OECD [2011]). I provide the first empirical evidence on how a price reasonableness policy affects procurement practices.

A priori, the effect of TINA's requirements on contract competition is not clear. It depends on how COs choose to comply: by requiring additional data or taking steps to receive multiple bids. Contract solicitations requiring additional data may decrease competition, as data management costs, weaker bargaining power, and greater legal risk may discourage some suppliers from bidding (Darrough [1993], Berger and Hann [2007], Bens, Berger, and Monahan [2011], Tomy [2019]). TINA requires suppliers to provide “cost or pricing data,” which is defined as all factual information that “prudent buyers and suppliers would reasonably expect to affect price negotiations significantly” (FAR 2.101). This information includes detailed cost line items and supporting facts, such as quotes, drawings, and specifications, which can be costly for suppliers to prepare. For instance, an Internet search reveals dozens of law and accounting consultancy firms offering to help suppliers reduce their costs of complying with TINA. Moreover, suppliers may be concerned that competitors could learn their proprietary information through bid protests or legal challenges, Freedom of Information Act requests (Sheffner [2019]), or by hiring former government employees. Prior literature finds that the proprietary costs of divulging confidential information can make companies, especially innovative firms, less willing to bid on government contracts (He et al. [2024]).

Alternatively, TINA's requirements may increase competition. This is because either of the COs' choices to comply with TINA (requesting additional data or taking steps to receive multiple bids) may encourage bidding. Solicitations that require additional data can increase suppliers' perceptions of fairness and attract competitors. However, requiring additional data represents a “cost” to both suppliers and the government when there are too few bids. COs must process the information and suppliers need time to submit it, delaying award times. To avoid these costs, COs may opt to promote bidding, which can also increase competition. Methods of encouraging supplier participation include relaxing bid specifications, seeking additional suppliers, and lessening restrictions governing who can bid (Kang and Miller [2022]). When deciding whether to require data or promote bidding to comply with TINA, COs will weigh multiple factors, including each choice's effects on their own effort, their ability to exercise discretion in choosing suppliers, the government's processing costs, the contract award timeline, suppliers' costs, bidding, and other factors. Given these tradeoffs, it is not clear whether TINA's requirements should increase or diminish competition for contracts.

For my empirical analyses, I use descriptive and quasi-experimental approaches including a regression discontinuity design (RDD). The treatment group contains contracts that exceed the TINA price threshold and are subject to its requirements (i.e., “affected contracts”).

I find evidence that COs try to avoid the costs associated with requiring additional data by encouraging more bids for contracts above the TINA threshold. COs are more likely to write solicitations that elicit multiple bids: they write fewer sole source contracts (i.e., only a single supplier is allowed to bid) and more open competition solicitations (i.e., all registered suppliers can bid). The prevalence of sole source contracts decreases by 3.89 percentage points (pp) among affected contracts (i.e., 14.7% less frequent than below the threshold). In addition, realized (actual) competition increases: The frequency of contracts with multiple bids is 4.39 pp (or 7.5%) greater for above-threshold contracts than for below-threshold contracts. These results are concentrated among contracts for which suppliers did not submit the data. Overall, this evidence suggests that COs promote bidding to adhere to TINA's requirements, and that this effect is stronger than any competition-decreasing effect due to additional costs to suppliers. These findings are surprising, as media reports and interviews with federal procurement experts suggest that most practitioners and even government employees expect TINA's requirements to primarily discourage competition.2 This belief is likely driven by TINA's emphasis on requiring cost or pricing data, with multiple bids merely serving as an exception to the data requirement.

I also study the regulation's effects on contract performance. TINA's requirements could lead to higher performance by enhancing COs' monitoring and management of affected contracts. Both requiring data and encouraging bidding can improve COs' familiarity with contracts, help COs to compose contracts with fewer errors, and allow them to present stronger arguments against renegotiations. In addition, greater familiarity with contract scope can mitigate uncertainty. This may allow the government to rely less on cost-plus contracts (i.e., paying cost reimbursements plus a profit margin to suppliers) and instead write more fixed-price contracts, which are simpler to monitor given that the suppliers bear all risks associated with price changes (Williamson [1971], Tadelis [2002]). On the other hand, to the extent that TINA's requirements increase competition, studies suggest this could diminish performance for two reasons. First, greater competition means more suppliers may meet the solicitation's bid evaluation criteria, reducing COs' discretion to favor suppliers based simply on their expected performance (Decarolis [2014], Coviello, Guglielmo, and Spagnolo [2018]). Second, greater competition may also induce suppliers to submit lowball bids that they try to renegotiate later (Alesina and Tabellini [2008]). I find that the performance of affected contracts improves: there are fewer contract modifications and cost overruns. Affected contracts also are less likely to be cost-plus type suggesting reduced uncertainty.3 Together, these results are consistent with prior literature that finds greater CO oversight leads to better performance and fewer cost-plus contracts (Warren [2014]).

Examining the performance of contracts that do not require the data in particular can provide further insight into the nature of TINA's impact on competition. My finding of increased competition for affected contracts could be explained by an alternative mechanism: coordination between COs and suppliers. COs may avoid requiring data from their preferred suppliers by opening bidding but indicate to their preferred suppliers beforehand that they will select them regardless. This sort of coordination would negate any benefits that greater competition could bring. If such coordination were to occur, COs would award contracts to the same suppliers without requesting any additional data, as if the threshold were not in effect. Therefore, we would expect no effect of the threshold on the performance or cost-plus pricing of such contracts. Focusing on the contracts where this kind of coordination is most likely—contracts that do not require the data—I find that, in addition to increased competition around the threshold, my performance and cost-plus pricing results hold. These findings suggest that COs do encourage genuine competition for above-threshold contracts.

An important assumption of my RDD analyses is that suppliers and COs do not engage in threshold gaming to avoid TINA's requirements. Additional tests confirm that the extent to which such manipulation occurs is economically insignificant and therefore unlikely to drive my results. In addition, a series of robustness checks validate my main results. First, placebo tests show that my results hold only when the TINA threshold is in effect. Second, heterogeneity tests show that my results are stronger for contracts that face greater exposure to TINA's requirements. Further, I find that TINA only induces an effect on noncommercial contracts, as expected given that commercial contracts are exempt from TINA's requirements. Finally, if COs can avoid requiring the data by encouraging bidding, then a substitution effect should occur between multiple bids and how often the accounting information are required. I find suggestive evidence of such a substitution effect.

This study makes several contributions. First, it expands our understanding of the use of accounting information in procurement contracts between buyers and suppliers. Watts and Zimmerman [1986] show that financial statement information can shape contract design. Costello [2013] documents that financial covenants based on firm performance can be used in supply contracts to alleviate risk due to asymmetric information. I contribute to this literature by documenting that a federal fair pricing policy that requires COs to request accounting data from suppliers or expect multiple bids increases competition, improves performance, and reduces cost-plus pricing.4

Second, my study contributes to the literature on government contracting (Samuels [2021], Brogaard, Denes, and Duchin [2021]), specifically the impacts of disclosure and transparency regulations on contract competition and performance. Recent studies find that public disclosure of procurement data (Duguay, Rauter, and Samuels [2023]) and publicization of contract solicitations (Coviello and Mariniello [2014], Lewis-Faupel, Neggers, Olken, and Pande [2016], Carril, Gonzalez-Lira, and Walker [2022]) affect contract competition and performance. In contrast, my evidence examines the effects of a fair pricing rule, which requires COs to request accounting data from suppliers or expect multiple bids, on the contracting process and the decisions made by COs. My findings are consistent with Warren's [2014] evidence that greater CO oversight increases competitive acquisition procedures and performance. Further, my study suggests that researchers should consider both TINA and cost or pricing data when analyzing federal contracts.

This study relates to literature on the effects of disclosure on product market competition (e.g., Gal-Or [1986], Darrough [1993], Berger and Hann [2007], Tomy [2019]). Bernard, Burgstahler, and Kaya [2018] show that firms go to great lengths to avoid proprietary disclosures, even managing firm size to stay below disclosure thresholds. This suggests some suppliers might avoid proprietary costs associated with TINA by not competing. Prior literature also finds that financial disclosures can increase competition by signaling investment opportunities to competitors (e.g., Bernard [2016], Granja [2018], Breuer [2021]). I find that a procurement regulation requiring private accounting disclosures can also bolster product market competition, though this occurs through a different mechanism: by COs encouraging competitive bidding to bypass TINA's disclosure requirement. As a result, suppliers need not provide their accounting information and COs avoid the cost of processing these disclosures. This study therefore also relates to the literature on information processing costs (e.g., Ball [1992], Healy and Palepu [2001], Blankespoor, deHaan, and Marinovic [2020]).

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the institutional context. Section 3 outlines the conceptual framework. Section 4 describes the samples used in this study. Section 5 defines the research design. Section 6 presents my results on the effects of TINA's requirements on bidding and execution outcomes. Section 7 contains several robustness checks. Section 8 concludes. Additional details are discussed in the appendix and the online appendix.

2 Institutional Context

In this section, I discuss public procurement contracting in the United States and I provide details about TINA.

2.1 FEDERAL PROCUREMENT CONTRACTING

In 2019, procurement accounted for $586 billion of the U.S. federal government's $4.4 trillion budget (CBO [2020], GAO [2020]). Federal procurement is governed by the U.S. Code, a set of legal statutes devised by Congress, as well as various regulations. The Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) implements the U.S. Code and contains detailed policies and procedures for federal procurement of goods and services.5

Most federal procurement contracts are “negotiated” contracts. In awarding these contracts, the government considers not only price but also contract terms and the suppliers' capabilities and performance history. Negotiated contracts are the type of contracts affected by TINA's requirements.

Awarding a negotiated contract involves several steps. First, the CO makes a solicitation, which is typically posted online.6 The solicitation contains the government's requirements, including technical specifications, time frames, and the information suppliers must submit with the proposal.

Second, the government receives proposals from suppliers. The proposals describe their technical approach, price, fee structure, and any additional information required. In most cases, the government can require suppliers to submit any type or quantity of data to establish that the price is reasonable. However, COs are directed to request the minimum data necessary, in order to reduce preparation costs, award times, and government resources expended (FAR 15.402(a)(3)). The most comprehensive data COs can require are “cost or pricing data,” which FAR 2.101 defines as “all facts that, as of the date of price agreement[…] prudent buyers and sellers would reasonably expect to affect price negotiations significantly.” This information includes accounting data, vendor quotes, and any facts contributing to the supplier's judgment of future costs. Cost or pricing data can be a major advantage to the government during negotiations, as it can be used to establish reasonable prices and lower suppliers' profits.

Next, the CO analyzes the proposals to determine whether the prices are “fair and reasonable” as well as realistic (FAR 15.404-1).7 To do this, COs must consider several factors: their own analyses of historical bid prices and market research, whether they received multiple bids, the quality of the suppliers, any data provided by the bidders, and any applicable regulatory thresholds such as the TINA threshold (discussed in section 2.2). The government then selects the winning proposal. Finally, after the government and the supplier negotiate direct costs, indirect costs, and fees, the contract is signed (awarded).

COs manage contract contents and the procurement process; therefore, they play a key role in the competition for and performance of contracts. They are responsible for establishing that prices are fair and reasonable, lowering contract and procurement operating costs, and promoting competition, among other duties (FAR Part 15 and FAR 1.102). The FAR grants COs substantial leeway in determining preaward contract characteristics, such as specifications, contract type (e.g., fixed price, cost-plus-fixed-fee), and solicitation procedures (e.g., private negotiations, sealed bids). COs determine if only one supplier can reliably meet the specifications and requirements and thus whether to solicit a proposal only from that source (i.e., a “sole source” contract per FAR 6.302-1 and FAR 2.101). They also decide whether to seek additional suppliers to increase competition. COs review any data submitted by suppliers. After the contract is awarded, they monitor contract performance (FAR Part 16). Government managers and auditors oversee the COs, who can face punishment for not complying with regulations such as TINA.

- (1) Determining whether adequate competition exists (in federal procurement, “adequate competition” exists when two or more independent bidders submit offers that satisfy the government's requirements).8

- (2) Relying solely on the COs' own judgment based on their market research and experience.

- (3) Requiring suppliers to provide private disclosures that support their proposed prices.

By requiring adequate competition or additional data, policies such as TINA reduce the extent to which COs can rely solely on their own judgment in establishing reasonable prices. I discuss TINA's requirements and how it impacts supplier disclosures further in the following section.

2.2 TRUTH IN NEGOTIATIONS ACT (TINA)

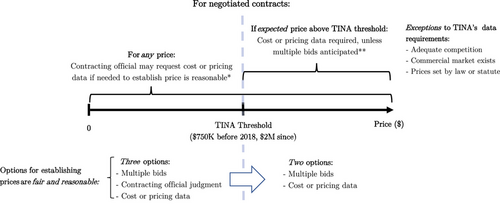

In 1962, after several high-profile incidents of unfair competitive practices and price manipulation involving collusion between government officials and suppliers, Congress passed the TINA.9 Per TINA, suppliers bidding on a negotiated contract must disclose cost or pricing data whenever COs expect the contract price to surpass the TINA threshold, unless multiple bids are anticipated (other exceptions may apply, as discussed below). The threshold is currently set at $2,000,000. Further, for contracts with an agreed (i.e., realized) price above the TINA threshold, suppliers must certify that to the best of their knowledge, “the cost or pricing data provided were accurate, complete, and current” (FAR 15.403-3). COs and governmental auditors must ensure that suppliers comply with TINA.10 Figure 1 summarizes the application of the TINA threshold.

TINA excepts from its requirements contracts whose prices are more likely to be reasonable. In such cases, requiring the data could unnecessarily drain procurement and supplier resources. These exceptions include contracts where COs anticipate adequate price competition (i.e., receiving two or more bids), contracts with prices set by law or regulation, and acquisitions categorized as “commercial items” for which there is already an established, competitive market.11 Regardless of TINA's requirements, the FAR enables COs to request uncertified cost or pricing data when necessary to ensure reasonable prices (see section A.1.1 of the online appendix and FAR 15.403-3 for additional details on certification). In certain cases, COs may also require certified data for below-threshold contracts if they obtain approval from their management (FAR 15.403-4(a)(2)).

In essence, TINA stipulates that for contracts above the threshold the government should protect its interest by requiring greater verification that prices are reasonable. For such contracts, procurement should rely less on COs' judgment and more on cost or pricing data and competition (FAR 15.403-4). COs can be subject to agency problems, such as colluding with bidders on contract awards and shirking. They can also make errors of judgment, especially as technology and production processes change. These problems can cause suppliers to perceive the process as unfair and reduce their desire to bid. For higher dollar contracts, these costs and the cost of an unreasonable price can increase substantially. TINA's requirements aim to alleviate these issues.12

Despite their intended benefits, TINA's requirements also impose various costs on suppliers and the government, which depend on whether COs require the data or encourage multiple bids. I begin by discussing the costs of COs requiring the data. First, suppliers must gather and prepare the cost or pricing data (using table 15-2 of FAR 15.408). If the data are to be certified, they must be the latest available across the supplier's entire enterprise (FAR 15.403-4(b)(2)). This requirement can involve time-consuming data collection “sweeps” that add 30 days on average to the award process according to one government estimate (Lorell, Graser, and Cook [2005]). Sweeps can disproportionately affect larger companies with multiple offices, though implementing a specialized certification system can be costlier for smaller companies. Second, cost or pricing data can be highly proprietary, deterring some companies who would otherwise like to contract with the government (Sheffner [2019], He et al. [2024]). Third, suppliers fear high pecuniary and reputational penalties for providing “defective” (i.e., incomplete, inaccurate, or outdated) cost or pricing data.13 Investigations can also be costly. Government claims against suppliers can also lower their supplier ratings in the Contractor Performance Assessment Reporting System and diminish their future prospects of contracting with the government (Heese and Pérez-Cavazos [2019]). Finally, the government must verify the additional information, which adds further time to the award process.

COs can decide to comply with TINA by encouraging bidding. To promote bidding, the CO can relax specifications (so a broader supplier base may bid), seek additional bidders, or make it easier to qualify new suppliers, each of which requires CO attention. Further, COs must verify any additional bids' prices are realistic. COs may also have less discretion to choose their favored suppliers who may perform better and require less oversight. Finally, involving more bidders increases the risk of bid protests and legal challenges.

Between October 1, 2015, and June 30, 2018, the TINA threshold was set at $750,000 per the FAR. However, on July 1, 2018, several agencies including the DOD raised their thresholds to $2,000,000. These “early adopter” agencies updated their thresholds before the FAR mandated it. They did so to reduce suppliers' data management costs and to align with the 2018 National Defense Authorization Act, which modified the U.S. Code and indicated an eventual FAR update. This threshold increase was the largest by dollar value in the history of TINA (see section B for details).

Table 1 presents the dollars obligated by the 15 largest federal agencies in fiscal years 2016–20, until emergency COVID procurement rules were instituted by the White House on March 13, 2020 (FR Proclamation 9994). The bottom row shows that early adopters' contracts comprised most federal contracts, in both number (81.1%) and dollar (84.6%) terms. The analyses in this paper thus focus on early adopter agencies' contracts around the $750,000 and $2,000,000 TINA thresholds (see section 4 for further discussion and a list of these agencies).14 In section 3, I discuss the conceptual underpinnings of this study and predict how the threshold affects contract bidding and execution.

| Fiscal Year | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Agency | Early Adopter? | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 (Until COVID) | Total | % of All Agencies |

| 1 | Department of Defense (DOD) | Yes | 65.9 | 71.7 | 81.6 | 94.0 | 29.8 | 343.1 | 78.6% |

| (36,978) | (36,082) | (35,067) | (40,174) | (11,598) | (159,899) | (74.2%) | |||

| 2 | Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) | No | 3.9 | 3.7 | 3.1 | 4.7 | 1.1 | 16.5 | 3.8% |

| (2,147) | (1,919) | (1,750) | (2,010) | (322) | (8,148) | (3.8%) | |||

| 3 | Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) | Yes | 2.7 | 4.2 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 0.4 | 12.1 | 2.8% |

| (1,623) | (1,297) | (1,274) | (1,462) | (285) | (5,941) | (2.8%) | |||

| 4 | Department of Homeland Security (DHS) | No | 2.9 | 2.6 | 2.9 | 2.6 | 0.5 | 11.5 | 2.6% |

| (1,279) | (1,237) | (1,321) | (1,099) | (284) | (5,220) | (2.4%) | |||

| 5 | Department of State (DOS) | No | 1.9 | 3.4 | 2.4 | 1.8 | 0.1 | 9.6 | 2.2% |

| (888) | (939) | (937) | (924) | (173) | (3,861) | (1.8%) | |||

| 6 | General Services Administration (GSA) | No | 1.9 | 2.6 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 0.6 | 8.8 | 2.0% |

| (1,321) | (1,325) | (1,147) | (1,272) | (388) | (5,453) | (2.5%) | |||

| 7 | Department of Justice (DOJ) | No | 1.4 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 5.6 | 1.3% |

| (970) | (894) | (820) | (835) | (379) | (3,898) | (1.8%) | |||

| 8 | Department of the Treasury (TREAS) | Yes | 1.8 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 4.9 | 1.1% |

| (558) | (520) | (305) | (391) | (119) | (1,893) | (0.9%) | |||

| 9 | Department of Transportation (DOT) | No | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 4.6 | 1.1% |

| (1,449) | (1,352) | (1,544) | (1,389) | (424) | (6,158) | (2.9%) | |||

| 10 | Department of the Interior (DOI) | No | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 3.3 | 0.8% |

| (805) | (688) | (727) | (770) | (128) | (3,118) | (1.4%) | |||

| 11 | Agency for International Development (USAID) | Yes | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 3.3 | 0.8% |

| (405) | (376) | (274) | (336) | (138) | (1,529) | (0.7%) | |||

| 12 | National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) | Yes | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 2.6 | 0.6% |

| (460) | (395) | (449) | (528) | (151) | (1,983) | (0.9%) | |||

| 13 | Department of Agriculture (USDA) | Yes | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 2.5 | 0.6% |

| (646) | (810) | (544) | (647) | (56) | (2,703) | (1.3%) | |||

| 14 | Department of Commerce (DOC) | No | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 2.0 | 0.5% |

| (381) | (300) | (304) | (307) | (72) | (1,364) | (0.6%) | |||

| 15 | Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) | No | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 1.8 | 0.4% |

| (93) | (69) | (66) | (81) | (38) | (347) | (0.2%) | |||

| All early adopter | 369.1 | 84.6% | |||||||

| agencies total: | (174,624) | (81.1%) | |||||||

- This table presents the total dollars (in billions) obligated to negotiated, noncommercial, prime contracts valued over $250,000, with counts of these contracts signed in parentheses, by fiscal year. The last two columns present totals and shares of all such federal contracts across the time period examined. This table ranks the top 15 federal agencies by total dollars obligated to such contracts. The sample follows the Full Baseline sample's time period, spanning between October 1, 2015 (i.e., the beginning of fiscal year 2016) and March 13, 2020 (i.e., the date the COVID emergency procurement orders were issued), as described in section 4. The last column contains the percentage that the dollars obligated by (contract counts of) a given agency comprise of the total dollars obligated (contract counts) for such contracts across all federal agencies. In the bottom right corner, totals and shares of contracts are presented for all early adopter agencies (including those not listed in this table). Early adopters are defined as agencies that deployed the $2,000,000 TINA threshold in 2018. See section 4 for the full list of early adopter agencies.

3 Conceptual Underpinnings

This section outlines my predictions of the effects of TINA's requirements on the following contract outcomes: whether cost or pricing data are required, competition, the frequency of cost-plus contracting, and contract performance.

3.1 COST OR PRICING DATA PREDICTIONS

TINA requires COs to request cost or pricing data for above-threshold negotiated contracts unless an exception applies (see figure 1). This requirement could lead COs to require cost or pricing data more often. Alternatively, COs may ignore TINA and request the data only when they believe the additional information will be useful, similar to below the threshold. However, I predict that TINA's requirements will produce a significant increase in the overall rate at which cost or pricing data are required.15

3.2 COMPETITION PREDICTIONS

The net effect of TINA's requirements on contract competition is not clear, as it depends on COs' choices between requiring data and taking measures to receive multiple bids. COs' decisions are influenced by personal factors (e.g., CO effort, discretion to choose favored suppliers, career concerns), taxpayer value considerations (e.g., government processing costs, award times, bargaining power, price impacts, performance, perceived fairness), and anticipated effects on bidding. Depending on COs' decisions, contract competition is subject to two countervailing effects, which I call the deterrence effect and the participation enhancement effect.

The deterrence effect has a negative impact on competition because costly disclosures force suppliers to manage more detailed accounting data, assume greater liability for defective data, lose bargaining power, and potentially incur proprietary costs (Darrough [1993], Tomy [2019]). Information leaks, bid protests, legal challenges, hiring of federal employees, and Freedom of Information Act requests can increase the risk that competitors might learn suppliers' proprietary information (Sheffner [2019]). In contrast, suppliers might be more innovative and more willing to work with the government when they can disclose less information (He et al. [2024], Breuer, Leuz, and Vanhaverbeke [2019]). In these ways, TINA may discourage competition. In fact, the 2018 National Defense Authorization Act relaxed TINA's requirements for lower priced contracts to reduce suppliers' data management costs. In my discussions with practitioners, they tended to expect the deterrence effect to dominate.

On the other hand, the participation enhancement effect has a positive impact on competition whether COs decide to promote bidding or require the data. As the FAR stipulates, COs should avoid requesting cost or pricing data unless it is necessary to establish that the proposed price is reasonable. For contracts expected to surpass the threshold, the primary way for COs to bypass TINA's data requirement is by taking measures to expect multiple bids. For example, COs can avoid designating contracts as sole source (i.e., having only one supplier available). They can also seek out bidders, allow open competition, make it easier to qualify new suppliers, or loosen specifications.16 Of course, encouraging bidding has its own costs. It requires attention, increases the risk of bid disputes and legal costs, and requires COs to verify that the offered prices are realistic. However, promoting bidding is often still less costly than requiring cost or pricing data, which entails processing costs, potentially higher contract prices, and project delays as submission of certified cost or pricing data can add weeks or even months to award times.

Competition may also increase due to COs promoting bidding to avoid audit involvement. Audit organizations, such as the DOD's Defense Contracting Audit Authority, often have special requirements regarding data received for TINA-covered contracts. In such cases, COs may need to provide additional documentation. Similarly, incurred-cost audits, which are common for cost-plus contracts, require extra effort from COs when suppliers submit the data. To avoid audits, COs may prefer to encourage bidding.

Requiring additional data may identify cheaper vendors who can deliver adequate goods or services, making it tougher for COs to justify selecting their preferred suppliers.17 Further, in the case of a sole source contract, it may be difficult to argue that only a single supplier is capable of providing the good or service. Requirements to disclose cost data thus may lead COs to relax contract specifications and open competition to alternative suppliers.

Last, improving suppliers' perceptions of fairness may also increase competition. Imposing greater disclosure requirements on preferred suppliers, who may previously have faced limited scrutiny, could signal increased impartiality on part of the COs. In turn, this perception could encourage more bidders to compete.

In these ways, TINA's requirements could increase competition. I predict that the participation enhancement effect will dominate (i.e., TINA's requirements are likely to increase competition).

3.3 PERFORMANCE PREDICTIONS

In this section, I discuss two opposing channels by which TINA's requirements may impact contract performance, in terms of renegotiations and cost overruns. The first channel is the performance enhancement effect. TINA's requirements may lead COs to better monitor and manage above-threshold contracts, resulting in improved contract performance (Warren [2014], Decarolis et al. [2020]). Both obtaining data and encouraging bidding can enhance COs' familiarity with contracts, enabling them to draft contracts that have fewer errors and provide better protection for the government. In addition, to the extent that TINA increases competition, this could deter suppliers from delivering poor performance for fear of losing future contracts to competitors. Indeed, COs are instructed to consider suppliers' past performance when they make award decisions (FAR 12.206). Finally, COs often use cost-plus contracts to shift risk to the government. This approach is necessary when uncertainties prevent COs from adequately defining requirements or prevent suppliers from accurately estimating costs for fixed-price contracting. Improved CO familiarity with contracts can reduce uncertainty and help COs write fewer cost-plus contracts, leading to more fixed-price contracts, which are easier to monitor. If the performance enhancement effect dominates, I would expect TINA's requirements to improve performance.

The second effect on contract performance is the price pressure effect. Increased competition may lead to lower offer prices. However, heightened competition may also diminish CO discretion and increase lowball bidding, both of which can result in poorer performance. First, if COs have less discretion to choose preferred (higher quality) suppliers because sufficiently capable, alternative suppliers submit lower bids, then contract performance may suffer. Second, lowball bidding, also called “buying in” (FAR 3.501-2), is a strategy by which suppliers lower their prices to undercut competitors; then, after winning the contract, they attempt to compensate for diminished profits through contract renegotiations (Decarolis [2014]).18 To the extent that TINA's requirements heighten competition, reduced CO discretion and lowball bidding may lead to more contract modifications and cost overruns (Alesina and Tabellini [2008]). Therefore, if the price pressure effect dominates, TINA's requirements should have a negative effect on performance.

I predict that TINA's requirements are likely to improve performance (i.e., the performance enhancement effect will dominate). I also predict that the threshold will have a negative effect on cost-plus contracts as long as the performance enhancement effect plays a role (regardless of whether it dominates the price pressure effect), because the price pressure effect should not affect cost-plus pricing. Figure 2 summarizes the predictions in this section.

4 Sample Construction

In this study, I focus on the TINA thresholds of $750,000 and $2,000,000, as discussed in section 2.2. The $750,000 threshold, which was in effect from October 1, 2015, to June 30, 2018, increased to $2,000,000 on July 1, 2018 for early adopter agencies. These agencies are the DOD, Department of Agriculture, Agency for International Development, Department of the Treasury, NASA, Department of Energy, and Department of Veterans Affairs.19 Such a large shift in the threshold is rare (see section B). The reason for this sizable increase was to save taxpayers money by lowering suppliers' data management costs.

The $750,000 and $2,000,000 TINA thresholds are particularly ripe for study because they are relatively far apart, which allows me to perform placebo and other robustness tests for stronger inference. These two thresholds were also effective during periods for which the FPDS–Next Generation populates the data used in this study. The FPDS tracks federal contracts from the time of award. Moreover, both thresholds are effective during time periods relatively free from contemporaneous confounding events, such as major U.S. conflicts or economic recessions.20

I focus on prime contracts signed by early adopters. I restrict my analyses to contracts that are the least likely to be exempt from TINA's requirements: negotiated, noncommercial contracts.21 I also exclude Small Business Innovation Research Program contracts due to a lack of price competition (see appendix A.1.2 for details). My “Full Baseline” sample includes all agency contracts that meet the above criteria and have prices between $250,000 and $3,000,000 during periods when either the $750,000 or $2,000,000 threshold was in effect. I exclude contracts below $250,000, because several early adopters used a simplified acquisition threshold of $250,000 during the study period.22 I use the Full Baseline sample primarily for descriptive exercises.

Next, I create two threshold-specific Baseline samples to use in my primary analyses. I do this in two steps. First, I split the Full Baseline sample into two periods corresponding with the effective periods for each threshold. Specifically, the “$750,000 threshold” sample contains contracts signed between October 1, 2015, and June 30, 2018. The “$2,000,000 threshold” sample includes contracts signed between August 6, 2018 (when the Department of Veterans Affairs deviation from FAR was signed) and March 13, 2020 (when the White House instituted emergency COVID procurement rules).23 Second, for each sample, I apply a bandwidth centered around the effective threshold. Section 5 provides details about the research design and variables used in my primary analyses.

The price ranges contained in these samples are likely to be material to even the largest private-sector companies. However, the federal government negotiates some contracts that cost billions of dollars. Thus, one might argue that contracts in the Baseline samples may be inconsequential to the government. Figure A.2 addresses this concern. Panels (a) through (c) show that the density of federal contracts decreases exponentially with price across a variety of price ranges. Panel (d) shows that the threshold-specific Baseline samples used for my analyses contain approximately 80% of all negotiated, noncommercial prime contracts signed by early adopters above the two TINA thresholds while each threshold was in effect. See section A.1.3 of the online appendix for further discussion of the price distribution. In sum, the price ranges examined in this study should be highly pertinent.

5 Research Design

The vector of contract outcomes I study, , contains variables related to cost or pricing data, competition, cost-plus contracts, and contract performance. CP Data is a dummy that equals 100 if cost or pricing data are required with the bid, and zero otherwise. The competition variables are Sole Source and Multiple Offers.27 Sole Source is an indicator set to 100 if the contract is awarded as part of a sole source solicitation (i.e., all but one bidder is excluded), and zero otherwise. Since COs can comply with TINA by taking steps to receive multiple bids, I also examine Multiple Offers, an indicator that equals 100 if the contract receives multiple bids, and zero otherwise.28 Importantly, Sole Source and Multiple Offers are not the converse of each other. A contract can have a solicitation where many bidders are allowed to bid but only a single bid is received (in which case, Multiple Offers = 0 and Sole Source = 0).

also includes contract performance and cost-plus type variables. Log(Number of Modifications) contains the natural logarithm of one plus the number of modifications (i.e., contract changes).29 Following Decarolis et al. [2020], I exclude modifications that are unlikely to have performance implications (e.g., contractor address changes).30 I also exclude changes that are anticipated at the initial contract signing (i.e., exercise of options). Cost Overrun is a dummy that equals 100 if the contract has a modification that results in a price increase, and zero otherwise. Cost-Plus equals 100 if a contract is cost-plus type, and zero otherwise. All variables are detailed in appendix A.

Columns 1, 2, and 3 of table 2 contain the means of the primary variables for contracts in the three Baseline samples used in this study: Full Baseline, $750,000 threshold, and $2,000,000 threshold. In the Full Baseline sample (column 1), approximately 18.5% of contracts require cost or pricing data, and an additional 0.9% formally waive the data requirement. Approximately 18.5% of contracts are cost-plus, 77.7% are fixed-price, and the rest are time and material contracts.31 The average contract in this sample receives 6.9 bids. Sole source contracts constitute 28.2% of contracts. 57.2% of contracts receive multiple bids, leaving 42.8% with one or zero offers. Contracts in this sample received 1.5 modifications on average. The unconditional likelihood of a contract having a cost overrun associated with a modification was 21.7%. Contracts written by three DOD bureaus (Army, Air Force, or Navy), which are by far the largest federal bureaus by procurement volume, comprise 78.7% of the sample.

| Baseline | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Full | $750,000 Threshold | $2,000,000 Threshold | |

| Cost or pricing data required (%) | 18.529 | 17.689 | 19.291 |

| (0.130) | (0.186) | (0.385) | |

| Cost or pricing data waived (%) | 0.939 | 0.936 | 0.715 |

| (0.032) | (0.047) | (0.082) | |

| Cost-plus contract (%) | 18.514 | 16.962 | 24.828 |

| (0.130) | (0.183) | (0.422) | |

| Fixed price contract (%) | 77.715 | 79.492 | 72.293 |

| (0.140) | (0.197) | (0.437) | |

| Number of offers received | 6.907 | 6.461 | 9.004 |

| (0.171) | (0.185) | (0.804) | |

| Sole source (%) | 28.269 | 26.740 | 30.080 |

| (0.151) | (0.216) | (0.448) | |

| Multiple offers (%) | 57.188 | 58.461 | 56.044 |

| (0.190) | (0.254) | (0.639) | |

| Open competition (%) | 38.981 | 41.914 | 37.124 |

| (0.164) | (0.241) | (0.472) | |

| Number of modifications | 1.530 | 1.421 | 1.852 |

| (0.008) | (0.012) | (0.023) | |

| Modification (%) | 60.978 | 58.557 | 69.968 |

| (0.164) | (0.240) | (0.448) | |

| Cost overrun (%) | 17.835 | 14.969 | 26.067 |

| (0.128) | (0.174) | (0.429) | |

| Initial duration (days) | 362.490 | 331.518 | 443.161 |

| (1.086) | (1.468) | (3.304) | |

| Definitive and purchase orders (%) | 16.492 | 15.476 | 19.758 |

| (0.124) | (0.176) | (0.389) | |

| Indefinite delivery vehicles (IDVs) (%) | 83.508 | 84.524 | 80.242 |

| (0.124) | (0.176) | (0.389) | |

| Supplies (%) | 16.973 | 16.567 | 16.717 |

| (0.126) | (0.181) | (0.364) | |

| Services (%) | 73.672 | 75.246 | 69.615 |

| (0.148) | (0.211) | (0.449) | |

| Research (%) | 9.355 | 8.187 | 13.668 |

| (0.098) | (0.134) | (0.335) | |

| Army, Air Force, and Navy (%) | 78.718 | 77.858 | 81.433 |

| (0.137) | (0.203) | (0.380) | |

| Observations | 88,967 | 41,993 | 10,492 |

- This table presents characteristics of negotiated, noncommercial, prime contracts awarded by early adopter agencies in the sample indicated, with standard errors in parentheses. Column 1 shows characteristics of contracts in the Full Baseline sample (which contains contracts with prices between $250,000 and $3,000,000 in both the $750,000 and $2,000,000 threshold periods). Column 2 presents characteristics of contracts in the $750,000 threshold Baseline sample (i.e., contracts from the Full Baseline sample that were signed during the $750,000 threshold period with prices between $250,000 and $1,250,000). Column 3 presents characteristics of contracts in the $2,000,000 threshold Baseline sample (i.e., contracts from the Full Baseline sample that were signed during the $2,000,000 threshold period with prices between $1,000,000 and $3,000,000). Early adopters are defined as agencies that deployed the $2,000,000 TINA threshold in 2018. See section 4 for the list of early adopter agencies and when the $750,000 and $2,000,000 TINA thresholds applied for each agency. All variables are defined in appendix A.

Per table A.1 in the online appendix, contracts that receive one or zero offers require cost or pricing data at a rate of 24.7% (16.3%) in the $750,000 ($2,000,000) threshold Baseline sample. In contrast, contracts that receive multiple offers require cost or pricing data at just under half the rate: 10.4% (7.4%) for the $750,000 ($2,000,000) threshold sample. This finding is consistent with COs requiring cost or pricing data more often when competition is expected to be inadequate for determining price reasonableness.

The RDD tests in this paper rely on the assumption that exceeding the threshold does not trigger other regulatory provisions that could affect the outcomes of interest. This appears to be the case. A search of the applicable federal regulations reveals that the TINA threshold does not coincide with any other significant regulatory provisions during the study period.32

6 Results

In this section, I present my primary results analyzing the effects of the TINA mandate on the requirement of cost or pricing data (i.e., comprehensive accounting information), contract competition, cost-plus pricing, and performance. In preliminary analyses, I test whether suppliers and COs manipulate contract prices to undercut the TINA threshold.

6.1 BUNCHING BELOW THE TINA THRESHOLD

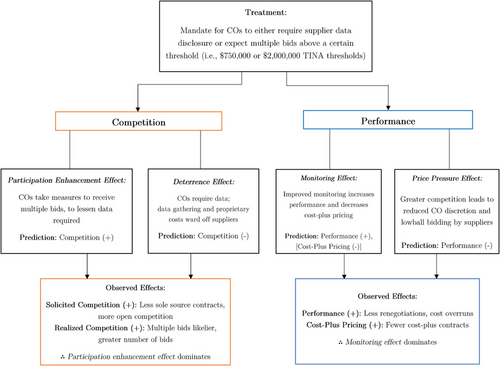

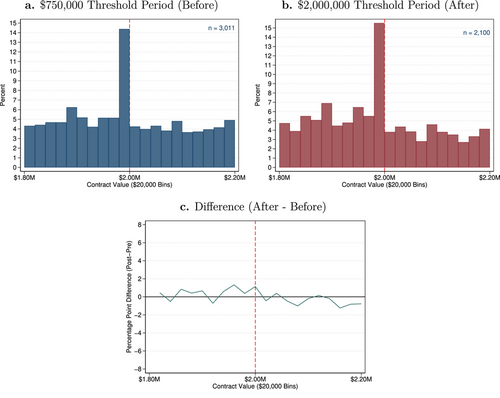

An assumption underlying my RDD analyses is that suppliers and COs do not engage in threshold gaming to avoid treatment to a significant degree (Saez [2010], Duguay, Rauter, and Samuels [2023]). In this section, I assess whether suppliers and COs violate this assumption by strategically manipulating contract prices to undercut the TINA threshold (i.e., “bunching” below the threshold). Following Palguta and Pertold [2017], I carry out two sets of tests to examine changes in the distribution of contracts below the $750,000 and $2,000,000 cutoffs due to the 2018 shift in the TINA threshold: graphical analyses and difference-in-differences estimations of the excess mass below the threshold.33

The extent to which threshold gaming occurs should be limited for several important reasons. First, the requirement for cost or pricing data under TINA is based on the prices COs expected before bidding, which are challenging for suppliers to manipulate. Second, any data required from suppliers are typically specified in the solicitation (prior to bidding) and are therefore largely independent of realized bid prices. COs may manipulate contract sizes to evade TINA's requirements by splitting contracts into smaller contracts. However, this should not occur often as it is explicitly prohibited (FAR 13.003(c)(2)(ii)), and COs are monitored by their management and government auditors.34

To the extent that suppliers or COs manipulate contract prices to undercut the threshold, I would expect a higher concentration of contracts at or just below the threshold value when the threshold is in effect compared to when it is not in effect. At the same time, when the threshold is in effect, I would expect an accompanying dip in the concentration of contracts just above the threshold where the manipulated contracts' prices would have been, compared to when the threshold is not in effect.

Figures 3 and 4 examine the price distributions of contracts from the Full Baseline sample around the $750,000 and $2,000,000 thresholds, respectively. Panel (a) of each figure shows the distribution of contracts before the 2018 TINA threshold change, panel (b) shows the distribution after the change, and panel (c) shows the pp differences in the distribution between the two time periods (i.e., after minus before). Figures 3 and 4 use right-endpoint inclusive price-bin widths of $10,000 and $20,000, respectively.

At first glance, the masses of contracts just below the effective TINA thresholds in figures 3(a) and 4(b) may seem to indicate contract bunching. However, these masses may occur for behavioral reasons rather than manipulation to circumvent any rules. In contracting, suppliers frequently bid at or just below round numbers, even when no policy-based threshold is in effect. Consistent with a round number preference, there are large masses of contracts at and below both TINA thresholds, even when the thresholds are not in effect (figures 3(b) and 4(a)). Similarly, there are relatively large concentrations of contracts at the round numbers $1,900,000 and $2,100,000 in figure 4(b), even when the $2,000,000 threshold is not in effect. To gain insight into how often suppliers and COs engage in manipulation to circumvent the TINA threshold, I exploit the timing of the threshold by focusing on the difference in distributions between the periods when the threshold is and is not in effect (i.e., panel (c) of each figure). This approach assumes that the density distribution around each threshold value would look the same before the threshold moved as after the threshold moved.

In figure 3(c), the concentration of contracts at and just below the $750,000 cutoff is no less prominent after the threshold changes to $2,000,000. Though there is a minor decrease in contracts in the few bins just below this cutoff, this evidence is inconsistent with prevalent bunching to avoid the $750,000 threshold. In section A.2.1 of the online appendix, I estimate the upper bound of the missing mass in the three bins below this threshold per Palguta and Pertold [2017] and find approximately 65 fewer contracts than predicted (p-value = 0.026), equivalent to only 0.15% of the $750,000 threshold Baseline sample.

Figure 4(c) examines the $2,000,000 cutoff value. As this panel shows, following the 2018 threshold change, there is an increase in contracts priced within the bin that includes contracts just below and at the new threshold of $2,000,000. The two bins below that one experience small positive changes after the threshold moved. Contracts priced just above the $2,000,000 threshold become somewhat less frequent. By themselves, these findings could be consistent with manipulation to avoid exceeding the $2,000,000 threshold, albeit only to a very small extent. Thus, following a similar approach as earlier, I estimate the upper bound of the excess mass to be approximately 172 contracts (p-value 0.001), or 1.6% of the $2,000,000 threshold Baseline sample.35 I cannot completely rule out that these masses of contracts just below either TINA threshold are driven partly by strategic manipulation. Although the evidence in this section suggests that the degree of change in bunching following the threshold increase is small and economically insignificant, the motives for bunching may change for some unspecified reason.

As an additional robustness check, I examine whether there is bunching of contracts requiring cost or pricing data below the TINA threshold. Given that TINA's requirement for certified cost or pricing data is based on realized prices, suppliers and COs may have more incentive to manipulate contract prices to undercut the threshold for solicitations requiring the certified data. That way, suppliers can avoid any additional liability posed by having to certify that the data are complete, accurate, and timely. In section A.2 of the online appendix, I restrict my bunching analyses to contracts requiring cost or pricing data, which yields even weaker evidence of manipulation.

6.2 COST OR PRICING DATA AND COMPETITION RESULTS

In this section, I present the results of RDD estimation of the effect of the TINA rule on both the requirement of cost or pricing data (i.e., comprehensive accounting information) and contract competition. TINA mandates that COs either require suppliers to disclose cost or pricing data or take measures to receive multiple independent bids for contracts above the threshold. See section 3 for the predicted effects of TINA's requirements on how often the data are required and on contract competition.

6.2.1 Cost or Pricing Data Results

In this section, I assess the effects of TINA on how often COs require suppliers to submit cost or pricing data with their bids. My empirical approach includes graphical and RDD analyses around the TINA threshold while it is in effect.

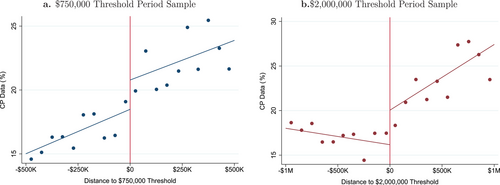

Figure 5 demonstrates the effect of TINA's requirements on whether cost or pricing data are required by threshold period. The y-axis is CP Data, the share of contracts requiring cost or pricing data. The x-axis is the contract price. In panel (a), as the $750,000 cutoff is crossed from the left, a sharp increase occurs in the fraction of contracts providing the data during the $750,000 threshold period. That fraction remains higher for all prices above $750,000. As shown in panel (b), during the period after the threshold increases to $2,000,000, the discontinuity shifts to $2,000,000. These results indicate that TINA's requirements significantly impact how often cost or pricing data are required for bids. Supplemental graphical analyses in section A.4 of the online appendix show that, as expected, these findings are even more pronounced for definitive and purchase order contracts (such contracts tend to be subject to less competition and are therefore less likely to be exempt from TINA's data requirement). They also show that commercial contracts, which are exempt from TINA, do not exhibit a discontinuity in the requirement of data across either threshold (see section 7.3 for further discussion on definitive, purchase order, and commercial contracts).

Columns 1 and 4 of table 3 present RDD analyses exploring the effects of TINA's requirements on the rate at which the data are required around each active threshold. Column 1 uses the $750,000 threshold sample and column 4 uses the $2,000,000 threshold sample. The dependent variable is CP Data. The coefficient of interest is (on ), which captures the effect of the TINA threshold on how often the data are required (see equation (1)). Columns 1 and 4 demonstrate that the threshold statistically and economically significantly increases the frequency with which cost or pricing data are required by 2.81 pp (p-value = 0.054) and 3.85 pp (p-value = 0.043) for contracts above the $750,000 and $2,000,000 thresholds, respectively, compared to below-threshold contracts. These estimated effects constitute 17.2% (= 2.812/16.32) and 21.9% (= 3.851/17.55) of the below-threshold means, respectively. Together, these results complement the visual evidence in figure 5 and provide evidence that TINA's requirements increase the rate at which cost or pricing data are required.

| $750,000 Threshold | $2,000,000 Threshold | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| CP Data (%) | Sole Source (%) | Multiple Offers (%) | CP Data (%) | Sole Source (%) | Multiple Offers (%) | |

| 2.812* | −3.893*** | 4.388*** | 3.851** | −3.927** | 6.306** | |

| (1.460) | (1.092) | (1.136) | (1.899) | (1.992) | (2.625) | |

| Distance | 0.005** | 0.006** | −0.007** | −0.001 | 0.003* | −0.006** |

| (0.002) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.003) | |

| * Distance | −0.002 | −0.002 | 0.005 | 0.006** | −0.002 | <0.001 |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.005) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.004) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Product-service code fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year-quarter fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Bandwidth (h, $1,000's) | 500 | 500 | 500 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 |

| Mean outcome (below threshold) | 16.32 | 26.51 | 58.46 | 17.55 | 30.20 | 55.50 |

| Std. dev. outcome | 36.96 | 44.14 | 49.28 | 38.04 | 45.92 | 49.70 |

| Observations | 41,993 | 41,993 | 37,769 | 10,492 | 10,492 | 6,024 |

- This table reports results for analyses of the effect of the TINA threshold on cost or pricing data (i.e., comprehensive accounting data) and competition variables. All columns present results from estimating equation (1) in section 5 by ordinary least squares. The coefficient of interest, on , represents the discontinuity (i.e., change in level) in the dependent variable at the threshold indicated. The dependent variables are defined as follows: CP Data equals 100 if cost or pricing data were required to be submitted with the contract proposal, and zero otherwise; Sole Source equals 100 if the contract was awarded as part of a sole source solicitation (i.e., where all but one bidder is excluded), and zero otherwise; Multiple Offers equals 100 if the contract received multiple bids and zero otherwise. The regressions in this table include the following controls: is the difference (in dollars) between the contract price and the threshold value shown for each column; Initial Duration is the expected duration of the contract at signing; a vector of dummies controlling for (1) set asides for small businesses and (2) all other set asides (e.g., women and minority-owned businesses). Contracts are from the threshold-specific Baseline sample indicated (i.e., negotiated, noncommercial, prime contracts awarded by early adopter agencies in the threshold period and within the bandwidth indicated) in each column. The $750,000 threshold period is between October 1, 2015, and June 30, 2018. Early adopters are defined as agencies that deployed the $2,000,000 TINA threshold in 2018. See section 4 for the list of early adopter agencies and when the $2,000,000 TINA threshold applied for each agency. Standard errors (in parentheses) are clustered by agency-contracting-office. *, **, *** denote statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels (two-tailed), respectively.

6.2.2 Competition Results

In this section, I use RDD tests to assess the effects of TINA's requirements on contract competition. As explained above, TINA requires that COs either request cost or pricing data from suppliers or take measures to receive multiple bids above the threshold. COs can bolster bidding in a variety of ways; They can avoid sole source contracts, relax contract specifications, simplify supplier qualification requirements, and seek additional suppliers.

Columns 2 and 5 of table 3 present estimates of the effect of the $750,000 and $2,000,000 TINA thresholds, respectively, on Sole Source, that is, how often COs adjust their frequency of designating contracts as sole source. The negative and statistically significant coefficients on indicate that sole source contracts experience a negative discontinuity at the TINA thresholds while the thresholds are in effect. Specifically, the prevalence of sole source contracts decreases by 14.7% (= 3.893/26.51) and 13.0% (= 3.927/30.20) for affected contracts above the $750,000 and $2,000,000 thresholds, respectively, compared to contracts below each threshold. Importantly, columns 3 and 6 show that contracts above both thresholds also are significantly more likely to receive multiple offers. The frequency of contracts with multiple bids is 7.5% (= 4.388/58.46) and 11.4% (= 6.306/55.50) greater above the $750,000 and $2,000,000 thresholds, respectively, than below them.36 These results are evidence that TINA's requirements increase competition. Figures A.7 and A.8 in the online appendix contain RDD plots that support these findings.

Together, these results indicate that the participation enhancement effect dominates the deterrence effect. This is a surprising finding, given that it differs from experts' expectations regarding TINA. However, it makes sense: COs promote bidding to reduce data provision, processing, and other costs. This competition-increasing effect outweighs any competition-decreasing effects due to suppliers' data management costs and proprietary concerns (see section 3.2).

When we compare the estimates of the threshold's effects on competition (i.e., 7.5%–14.7% from columns 2, 3, 5, and 6) to its effects on how often cost or pricing data are required (i.e., 17.2%–21.9% from columns 1 and 4), it appears that COs might require cost or pricing data more frequently than they promote bidding to satisfy TINA's requirements. However, these differences lack power for precise inferences (e.g., p-value = 0.302 when we compare the economic significance of 17.2% implied by column 1 to that of 7.5% for column 2).

In untabulated results, I further examine what drives these competition results. Do COs promote bidding, or are suppliers more likely to perceive solicitations requiring the data as fairer? I find that these competition results hold only for contracts that do not require cost or pricing data. This finding suggests COs' encouragement of bidding for affected contracts indeed plays a role in these results.37

From the results in this section, it is not clear whether COs spur a meaningful increase in competition. COs may promote bidding “on paper” by soliciting more bids, but signal (directly or indirectly) beforehand to their favored supplier that the COs will choose them regardless. Though institutional factors make such coordination unlikely, in the following section, I explore this question further by examining how the threshold affects contract performance and cost-plus pricing. Additionally, if COs can reduce the need for cost or pricing data by increasing bidding, the primary mechanism underlying the participation enhancement effect, then a substitution effect should occur between multiple bids and how frequently the data are required. In section 7.4, I show suggestive evidence of such a substitution effect.

6.3 PERFORMANCE AND COST-PLUS PRICING RESULTS

In this section, I examine the effects of the TINA threshold on contract performance and cost-plus pricing. As described in section 3.3, I test whether the performance enhancement effect or the price pressure effect dominates at each value of the TINA threshold. Table 4 presents the results. This table features the coefficient on from estimating equation (1) with performance and cost-plus variables as the dependent variables, using two types of samples. First are the threshold-specific samples, which are for the focal results, shown in the top row. Examining the $750,000 threshold, we see that the coefficient on in column 1 indicates a modest improvement of 3.0% in the rate of renegotiations for affected contracts. The statistically and economically significant negative coefficient on in column 2 indicates that affected contracts are 12.6% (= 2.98/23.63) less likely to experience a cost overrun. Column 3 shows a small but statistically insignificant decrease in the use of cost-plus pricing for affected contracts.

| $750,000 Threshold | $2,000,000 Threshold | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Log(Number of Modifications) | Cost Overrun (%) | Cost-Plus (%) | Log(Number of Modifications) | Cost Overrun (%) | Cost-Plus (%) | |

| Baseline | −0.029** | −1.868** | −0.957 | 0.024 | 2.982 | −2.612* |

| (0.014) | (0.787) | (0.765) | (0.026) | (1.858) | (1.419) | |

| Cost or pricing data not required | −0.026* | −2.165** | −0.921 | 0.023 | 3.130 | −2.987* |

| (0.016) | (0.917) | (0.660) | (0.030) | (2.048) | (1.614) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Product-service code fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year-quarter fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Bandwidth (h, 1,000's) | 500 | 500 | 500 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 |

| Mean outcome (Baseline, Below Threshold) | 0.74 | 16.79 | 22.30 | 0.87 | 27.94 | 28.39 |

| Std. dev. outcome (Baseline) | 0.69 | 37.38 | 41.63 | 0.68 | 44.88 | 45.10 |

| Observations Baseline | 41,993 | 41,993 | 41,993 | 10,492 | 10,492 | 10,492 |

| Cost or pricing data not required | 34,565 | 34,565 | 34,565 | 8,467 | 8,467 | 8,467 |

- This table reports results for analyses of the effect of the TINA threshold on contract performance and cost-plus contract type variables. All columns feature the coefficient on from estimating equation (1) in section 5 by ordinary least squares for two types of samples: (1) the threshold-specific Baseline samples (first row) and (2) the subset of contracts in each Baseline sample that did not require cost or pricing data (second row). The coefficient on represents the discontinuity (i.e., change in level) in the dependent variable at the threshold indicated. The dependent variables are defined as follows: Log(Number of Modifications) is the natural logarithm of one plus the number of modifications; Cost Overrun equals 100 if the contract had a modification that resulted in an increase in the contract price and zero otherwise; Cost-Plus equals 100 when the contract is of cost-plus reimbursement type, and zero otherwise. The regressions in this table include the following controls: is the difference (in dollars) between the contract price and the threshold value shown for each column; a interaction term; Initial Duration is the expected duration of the contract at signing; a vector of dummies controlling for (1) set asides for small businesses and (2) all other set asides (e.g., women and minority-owned businesses). Contracts are from the threshold-specific Baseline sample indicated (i.e., negotiated, noncommercial, prime contracts awarded by early adopter agencies in the threshold-period and within the bandwidth indicated) in each column. The $750,000 threshold period is between October 1, 2015, and June 30, 2018. Early adopters are defined as agencies that deployed the $2,000,000 TINA threshold in 2018. See section 4 for the list of early adopter agencies and when the $2,000,000 TINA threshold applied for each agency. Standard errors (in parentheses) are clustered by agency-contracting-office. *, **, *** denote statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels (two-tailed), respectively.

Next, I examine the $2,000,000 threshold. Columns 5 and 6 show that the threshold's effects on contract performance are statistically insignificant. As column 6, shows, the cost-plus type becomes 9.2% (= 2.612/28.39) less common among affected contracts (significant at the 10% level). This finding suggests that TINA's requirements may help COs to write fewer cost-plus contracts as the government's information environment improves. Figures A.9 and A.10 in the online appendix provide the corresponding RDD plots, which align with these results.

Taken together, this evidence suggests that the performance enhancement effect dominates the price pressure effect, as monitoring and the subsequent performance of contracts improve due to TINA's requirements. This effect may occur at least partly due to COs originating fewer cost-plus contracts. Figure 2 summarizes the observed effects on cost or pricing data, competition, cost-plus pricing, and performance.38

As mentioned in section 6.2.2, my competition results may have an alternative explanation. COs may promote bidding to avoid requiring their favored suppliers to provide data; however, they may directly or indirectly signal to those suppliers before bidding that they will select them regardless.39 Such coordination is unlikely due to institutional factors (e.g., illegality, monitoring by management, bid protests), but if it occurred, it could negate any potential benefits from increased bidding (e.g., reduced prices). Such collusion could also harm competitors and the government by wasting resources. Of course, one cannot observe the counterfactuals: We do not know the number of bidders and who the winners would have been if TINA's requirements were not in effect. Studying the effect of increased bidding on equilibrium prices presents its own estimation challenges as well. However, if such collusion occurs—if COs simply select the same suppliers and do not require any additional data as they would have if the TINA threshold were not in effect—the threshold should not affect contract performance or cost-plus pricing.

Using this reasoning, I investigate this alternative hypothesis by testing whether my performance and cost-plus type results hold for the subsample of contracts that do not require cost or pricing data. The coordination hypothesis predicts insignificant effects, whereas if COs meaningfully increase bidding, then my results should still hold. As shown in the second row of table 4, my previous results are unchanged. This finding suggests that the competition results are not primarily driven by COs increasing bidding “on paper.” Rather, COs meaningfully encouraging bidding appears to play a role in my results.40

7 Robustness Checks

In this section, I present the results of robustness checks of my main findings from section 6. First, I discuss the results of placebo tests and alternative specifications for my main RDD analyses. Next, I explore whether my main results are stronger (weaker) for contracts with greater (less) exposure to TINA's requirements, as expected. Then, I demonstrate that a substitution effect exists between how often COs require cost or pricing data and multiple bids are received (as would be expected if COs can avoid requiring the data by encouraging bidding). Finally, I show my primary results hold using a difference-in-discontinuities design, exploiting the 2018 TINA threshold change as a natural experiment.

7.1 PLACEBO TESTS

In this section, I perform placebo RDD tests to further validate my findings in section 6. For these tests, I examine the effect of the $750,000 and $2,000,000 cutoffs on each outcome variable from section 6 when these thresholds are not in effect. These tests use samples obtained by applying the same filters as the threshold-specific Baseline samples, but they use alternative (placebo) time periods.41 In contrast to my main results in tables 3 and 4 from the time periods during which the thresholds were in effect, in these alternative time periods I expect the coefficient on , which now captures the effect of the placebo threshold on the contracting outcome, should by and large be insignificant.

The placebo results are presented in tables A.7 and A.9 in the online appendix. Importantly, all estimated coefficients on for the Baseline samples (the first row of each table) are statistically and economically insignificant, as expected (the remaining rows in these tables relate to heterogeneity tests discussed in section 7.3). These findings provide additional evidence that my primary results are driven by TINA's requirements.

7.2 ALTERNATIVE RDD SPECIFICATIONS

In this section, I test the robustness of the main RDD results from section 6 to different specifications.

Table 5 presents RDD results using alternative specifications for the dependent variables CP Data, Multiple Offers, and Log(Number of Modifications). Columns 1 through 3 of table 5 contain the results of estimating equation (1) around the $750,000 threshold, adding a quadratic term and its interaction with to the model. My findings are unchanged. Columns 4 through 6 show the results of estimating equation (1) using a bandwidth of $300,000 instead of $500,000. My main findings are also robust to this alternative specification.42

| Quadratic Distance Controls | Alternative Bandwidth | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| CP Data (%) | Multiple Offers (%) | Log(Number of Modifications) | CP Data (%) | Multiple Offers (%) | Log(Number of Modifications) | |

| 4.088** | 3.872** | −0.033* | 3.345** | 4.790*** | −0.028* | |

| (1.776) | (1.729) | (0.020) | (1.634) | (1.468) | (0.016) | |

| Distance | −0.007 | −0.005 | 0.001* | 0.003 | −0.007 | 0.001*** |

| (0.007) | (0.009) | (0.001) | (0.004) | (0.005) | (0.001) | |

| * Distance | 0.009 | 0.007 | 0.001 | 0.001 | −0.001 | 0.001 |

| (0.016) | (0.017) | (0.001) | (0.009) | (0.010) | (0.001) | |

| Quadratic distance controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Other controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Product-service code fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year-quarter fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Bandwidth (h, $1,000's) | 500 | 500 | 500 | 300 | 300 | 300 |

| Mean outcome (below threshold) | 16.32 | 58.46 | 0.61 | 17.37 | 56.51 | 0.65 |

| Std. dev. outcome | 36.96 | 49.28 | 0.63 | 37.88 | 49.58 | 0.65 |

| Observations | 41,993 | 37,769 | 41,993 | 20,541 | 18,477 | 20,541 |

- This table reports results for analyses of the effect of the TINA threshold on cost or pricing data (i.e., comprehensive accounting data), competition, and performance variables using alternative RDD specifications. All columns present results from estimating equation (1) in section 5 by ordinary least squares, but columns 1 through 3 include a second-degree polynomial term and its interaction with , whereas columns 4 through 6 use an alternative bandwidth, , of $300,000. The coefficient of interest, on , represents the discontinuity (i.e., change in level) in the dependent variable at the threshold indicated. The dependent variables are defined as follows: CP Data equals 100 if cost or pricing data were required to be submitted with the contract proposal, and zero otherwise; Multiple Offers equals 100 if the contract received multiple bids and zero otherwise; Log(Number of Modifications) is the natural logarithm of one plus the number of modifications. is the difference (in dollars) between the contract price and the threshold value shown for each column. The regressions in this table include the following other controls: Initial Duration is the expected duration of the contract at signing; a vector of dummies controlling for (1) set asides for small businesses and (2) all other set asides (e.g., women and minority-owned businesses). Contracts are from the $750,000 threshold Baseline sample (i.e., negotiated, noncommercial, prime contracts awarded by early adopter agencies in the $750,000 threshold period) and within the bandwidth indicated in each column. The $750,000 threshold period is between October 1, 2015, and June 30, 2018. Early adopters are defined as agencies that deployed the $2,000,000 TINA threshold in 2018. See section 4 for the list of early adopter agencies and when the $2,000,000 TINA threshold applied for each agency. Standard errors (in parentheses) are clustered by agency-contracting-office. *, **, *** denote statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels (two-tailed), respectively.

7.3 HETEROGENEITY TESTS

In this section, I devise a set of heterogeneity tests to further explore whether the results in section 6 are driven by TINA's requirements. These tests analyze how the effects of the threshold vary across different samples of contracts that are likely to experience stronger or weaker effects due to TINA's requirements (see section A.5.1 of the online appendix for details and the full results).

First, I compare the effects of TINA's requirements on IDVs and non-IDVs (i.e., definitive and purchase order contracts). Relative to non-IDVs, IDVs entail more competition: They are associated with fewer sole source contracts and more bids (per table A.4 in the online appendix). Therefore, IDVs should more often be exempt from the requirements, relieving COs from having to take any additional actions to comply with TINA. Consistent with this prediction, I find that non-IDVs exhibit statistically stronger effects from the threshold than IDVs in terms of data required and performance.