INFORMALITY AS THE UR-FORM OF URBANITY: Keeping the Ur- in Urban Studies

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Melbourne, as part of the Wiley - The University of Melbourne agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Abstract

After 50 years of research on urban informality, why is it that we seem unable to either clearly define this concept or move beyond it? On the one hand, urban informality is identified with ‘slums’ and substandard outcomes, on the other, with deregulated markets and neoliberal urbanism. Yet it is also identified as a self-organized urbanism that adds vitality, affordability, diversity, creativity and adaptability to the city—a form of urbanity that embodies the ‘right to the city’ and urban commoning. How are we to understand this paradox and move beyond the informal/formal as a binary distinction? If informality is more than a lack of formality, then what is informality-in-itself? The key argument here is that urban informality is the original form of urbanity—the ur-form—while formal urbanism is its necessary counterpart. Informal urbanism is not a lack of formality, but the ground from which the formal emerges. This inversion changes the way we understand the city as an in/formal assemblage. While rampant informality may seem the very antithesis of urban planning, to erase it is to kill urbanity itself. The challenge is to engage this paradox—planning for the unplanned, keeping the ur- in urban studies.

Introduction

ur-form: ‘primitive, original or earliest’ form

(Oxford Dictionary)

He is not alone in seeking to understand the informal as normal and formality as the exception (Watson, 2009; Marx, 2009; McFarlane and Waibel, 2012). However, this is more than a problem of language—what is the nature of urban informality-in-itself? The key argument here is that urban informality is best understood as the ground of formal urbanism, as the earliest, original or ur-form of urbanity. Formal urbanism is the means through which the productive forces of urbanity are stabilized, managed, rendered transparent, taxed and controlled. This is not to suggest any kind of reductionism or essentialism that would continue the binary thinking that has plagued this field. To say that the informal comes first is not to establish an order of priority but a sequence. This inverted conceptual framework—where the formal emerges from the informal—is useful for understanding how cities are produced, how they change and are stabilized, how power is practised, and how livelihoods are established and sustained. This observation means that we need a much better understanding of both informality-in-itself and its complex interrelations with the formal.the notion of informality is problematic in that it constitutes the gaze of the state as the superior, legitimate and authentic one … informality is a relational concept: it is tied to, and legitimates, ‘the formal’ … informality is ‘the Other’, bound into a teleological relationship with the formal, but unable to ever achieve it (Pratt, 2019: 613).

My argument will take a somewhat circuitous route. The first step is to understand urban informality as a paradox. Research on informal urbanism broadly encompasses practices of informal settlement, street vending and informal public transport as well as temporary/tactical urbanism, urban commoning and citizen-driven planning, in cities of both the global North and South. These informal practices produce a gamut of urban outcomes that cannot be reduced to either problems or virtues. Informal settlement undermines urban planning and construction standards yet represents the primary mode of production of affordable housing and neighbourhood infrastructure in rapidly growing cities in the global South. Informal street vending and rickshaws often exacerbate congestion and undermine labor and safety laws, but also sustain livelihoods as they add amenity, mobility, vitality, creativity and agility to the city. Temporary and tactical urbanism in the global North is both ‘austerity urbanism’ and a vital form of ‘urban commoning’. The paradox may be stated as follows. Urban informality is at once the antithesis of urban planning and a form of radical democracy that embodies the ‘right to the city’. It services the deregulated neoliberal state while also being a form of resistance to it; at once a weapon of the powerful and of the weak.

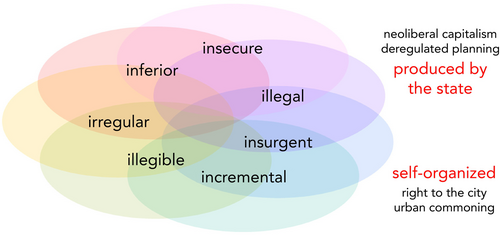

The second step is to tease apart the multiple definitions of informal urbanism as a contested discourse, to understand it as a relational assemblage of interconnected and overlapping characteristics that will be portrayed here as seven i's of urban informality—illegal, insecure, inferior, irregular, incremental, illegible and insurgent. This model embodies the ways informality cuts across the formal structures of state regulation (illegal, irregular), the ways it is geared toward socio-economic inequality (insecure, inferior), its highly adaptive capacities (incremental), its ability to hide itself (illegible), and its politics (insurgent). Informal urbanism embodies multiple modes and practices in a manner that resists reduction to a singular definition and exceeds any definition as the inverse of the formal.

The third step is to move beyond binary thinking to a critique of the ontology of urban informality, as something more than an exception to the formal—informality-in-itself. Rather than the inverse of the formal, informality is the earliest or ur-form of urbanism, and formal urban planning is largely a means of regulating its excesses.

Finally, I seek to ground these ideas in the most common modes of informal urbanism: informal settlement, street vending and transport. An excursion into archaeology suggests that the earliest ancient towns have a morphogenesis similar to contemporary informal settlements. Likewise, informal street vending can be understood as the ur-form of markets, and walking as the ur-form of public transport. From this view cities are not primarily formal artefacts that become infiltrated by informal practices; rather, informal connections, desires, encounters, flows and practices are the productive forces of urbanity that become encoded and formalized by the state. While cities as extensive agglomerations of buildings and streets always show evidence of both formal and informal processes (‘top-down’ and ‘bottom-up’ planning if you prefer), ‘urbanity’ is grounded in sustained intensive encounters and exchanges between strangers. Informal urbanism is at the heart of what makes cities work and sustains livelihoods. Yet the paradox does not disappear because ‘urbanity’ is also defined in terms of codes of courtesy and convention that are formalized to varying degrees. What is at stake here is the way we think about how cities and livelihoods are produced, sustained and controlled, how they become resilient and how they change, and how power is practised for better or worse.

Neoliberal urbanism

The paradox I have outlined here has been apparent since the emergence of the informality framework in the 1970s when Hart (1973) highlighted the ‘informal’ as a sector of the economy that escaped formal measures. The discourse of informality spread rapidly in the 1970s through the ILO, World Bank and the UN where it meshed well with the neoliberal thinking that was soon to dominate development practices. The idea of the urban poor bootstrapping their way out of poverty resonated with the push for deregulated markets, lower taxes and less state control. Bromley (1978) argued that the concept of the informal appealed because it deflected attention from the effects of monopoly capitalism, and offered the prospect of ‘helping the poor without any major threat to the rich’ (ibid.: 1036). The formal/informal framework was also seen in part as a way of rethinking relations between tradition and modernity, with the informal as a kind of pre-capitalist ‘petty commodity production’ (Moser, 1979).

For Roy, informality is a mode of urban production that is primarily identified with the capitalist state: ‘informality is not a pre-capitalist relic or an icon of “backward” economies. Rather it is a capitalist mode of production par excellence’ (Roy, 2009b: 826).Informality then is not a set of unregulated activities that lies beyond the reach of planning; rather it is planning that inscribes the informal by designating some activities as authorized and others as un-authorized, by demolishing slums while granting legal status to equally illegal suburban developments (Roy, 2009a: 10).

Roy's work has also spawned a critique of what is known as ‘elite informality’ or ‘informality from above’ (Tonkiss, 2013), based on the ways social, political, and economic elites engage in informal practices of power. These methods encompass a broad range of practices, from the use of elite influence to generate exceptions to formal planning controls (Moatasim, 2019), middle-class defence of street vendors (Schindler, 2017), and elite forms of tactical urbanism in the global North (Devlin, 2017). Elite informality preys upon the ambiguity and adaptability of informal urbanism, blurring the boundary between informality and corruption. Elites use influence and institutional power but operate under the cover of informality (van Gelder, 2013; Chiodelli and Moroni, 2014). While it is crucial to understand the ways self-organized processes can be co-opted to extract profit or elite privilege, the concept of ‘informality from above’ is a contradiction in terms. We need a better expression to critique the differences between ordinary informality and the various forms of bureaucratic or political ‘corruption’ and elite ‘influence’, as well as the illegal practices of ‘land traffickers’ and ‘land mafias’.

Right to the city

While the concept of informality as an economic sector emerged in Africa, a parallel discourse on ‘squatter settlements’ emerged over a similar period in Latin America (Mangin, 1967). Here the focus was on the right to housing in the form of ‘freedom to build’, harnessing the productivity of ‘housing as a verb’ (Turner, 1972). ‘Squatter’ housing soon became known as ‘informal settlement’ as part of the broader discourse of informal urbanism, where the paradox was soon recognized. Peattie (1987) saw the definitional fuzziness of ‘informality’ as crucial to its appeal as a label that worked to legitimate both the rights of citizens and market-based approaches to development.

The ‘right to the city' discourse stems largely from Lefebvre ([1968] 1991), linked in turn to the situationists and other urban social movements of the 1960s. At the more general level, this is the right to challenge the commodification of public space as capitalism expands and reduces the use value of urban land to exchange value. The right to the city embodies not only rights of access and appropriation of public space, but rights to the production of urban space. For Lefebvre, urban space is at once a means of production and a product, so the right to the city involves a right to control a means of production. Yet for all the energy spent in proclaiming this right, it remains poorly defined. For Purcell (2016), it is linked to the Hobbesian contract between citizen and state, where the legitimacy of the state rests on its capacity to ensure the livelihoods of its citizens. It follows that the legitimacy of informal urbanism—especially informal settlement and street vending—rests on conditions where the state cannot or will not ensure livelihoods. From this view, the right to the city is based on a natural right, mediated by our contract with the state.

This side of the paradox can also be seen as rooted in the work of those such as Jacobs, whose celebration of urban difference and informality was central to how cities work: ‘city diversity is the creation of incredible numbers of different people and different private organizations, with vastly different ideas and purposes, planning and contriving outside the formal framework of public action’ (Jacobs, 1961: 241). In his book Seeing Like a State, Scott argues that the state is inevitably invested in the imposition of an administrative order that is at once pragmatic and aesthetic–a codification of the complexities of everyday life to simple rules in a manner that excludes informal local knowledge. For Scott (1998: 82): ‘The utopian, immanent, and continually frustrated goal of the modern state is to reduce the chaotic, disorderly, constantly changing social reality beneath it to something more closely resembling the administrative grid of its observations’. The formal control of the state is necessarily dependent on ‘a host of informal practices and improvisations that could never be codified’ (Scott, 1998: 6). From this view, informality embodies an autonomous capacity of marginalized populations to resist the state through what he terms 'weapons of the weak' (Scott, 1985).

Seven i's of urban informality

It is not the goal here to resolve the paradox of urban informality, but to understand it better as a relational concept. I now want to tease apart some overlapping definitions, properties, and characteristics of urban informality, each of which provides a partial understanding and in which the interrelations are crucial. They are diagrammed in Figure 1 and presented here as seven i's of urban informality: illegal, inferior, insecure, irregular, illegible, incremental and insurgent:

(source: the author)

illegal

Insofar as informal urbanism violates the legal statutes of the state, it becomes identified with illegality—‘squatter’ settlements are defined as operating outside the law. Informality is often practiced on the edges of the law, or ‘in light of the law’ (Chiodelli and Moroni, 2014: 162). This is the primary definition used in the literature on informal urbanism; whether informality is defined as ‘beyond state control’ or as ‘produced by the state’—it is the power of the state to define what is legal that defines informality (Roy, 2005).

inferior

Insofar as the laws of the state uphold certain quality and safety standards, informal urbanism is often implicitly identified as inferior. When the phrase ‘informal settlement’ is used as a euphemism for ‘slum’, it identifies sub-standard and unsafe living conditions (Dovey et al., 2021). In this sense, the city can be seen as contaminated by informality, with opposition to it (such as slum clearance) as a form of urban cleansing (Appadurai, 2000).

insecure

When formal statutes provide security of land tenure and occupation, informal urbanism is identified with insecurity or precarity—a persistent threat of eviction, demolition, or prosecution. Yiftachel (2009) identifies urban informality with the power of the state to hold certain communities or territories in a precarious state that he terms ‘gray space’—a ‘permanent temporariness’ without the rights of citizenship and under constant threat of eviction. Tenure cannot be understood strictly within a legal framework because of the many forms of de facto, customary, or perceived tenure conditions (van Gelder, 2013).

irregular

Insofar as formal planning codes and building regulations tend to impose a regulated order on the urban morphology, informal urbanism can be identified by irregularity of form. Informal settlements are often identified in aerial photographs by the irregularity of street and laneway networks (Kuffer et al., 2016; Dovey and Kamalipour, 2018). A highly regulated spatial order with the logic of the grid is essential to what Scott (1998) calls ‘seeing like a state’. Visible images of irregularity cut across aesthetic regimes of both the state (law and order) and capital (place branding); and become crucial to the politics of eviction and upgrading (Ghertner, 2015).

illegible

While the irregularities of street vending and settlement can produce potent imagery, especially in its extremes, informal urbanism also has a capacity to hide and camouflage its practices. It is steeped in forms of local knowledge that cannot be codified and are largely illegible to the state (Scott, 1998; McFarlane, 2011). When informal urbanism is identified as the ‘quiet encroachment of the ordinary’ (Bayat, 1997), ‘off the map’ (Robinson, 2002), the ‘unmapping’ of urban space (Alsayyad and Roy, 2004), or ‘hiding in plain sight’ (Simone, 2019), this all implies illegibility. Illegibility is produced by both the desire to not be seen, and the desire to not see.

incremental

Informal urbanism is characterized by small-scale, self-organized, highly adaptive and iterative increments of change (Dovey and Kamalipour, 2018). Informal settlement is often produced by room-by-room accretion—an urbanism of continuous encroachment where large numbers of insignificant events bring transformational change. Incrementality is strongly connected to the illegibility of quiet encroachment and the irregular outcomes of a highly adaptive process.

insurgent

Urban informality embodies practices of power that infiltrate the structures of state power; informal practices are ‘weapons of the weak’ (Scott, 1985), forms of ‘insurgent citizenship’ (Holston, 2008) and of ‘planning against the state’ (Purcell, 2016); all of which returns us to the notion of illegality.

These overlapping characteristics of urban informality are diagrammed in Figure 1, where it is possible to discern the paradox as a tension between the upper and lower clusters. It is the illegal, insecure and inferior dimensions that draw the critique of urban informality as a product of neoliberal capitalism and deregulated planning, while the irregularity, illegibility, incrementality and insurgency suggest self-organized forms of radical democracy and right to the city. The challenge is not to choose between these characteristics and definitions but to enter into and understand this antinomous condition. Informal urbanism is a mode of production that works both with and against the state; and as we shall see, without the state.

These seven i's of urban informality are, of course, somewhat arbitrary, and there could be others—independent, illegitimate, invalid … There could indeed be seventeen rather than seven, and they could all start with an ‘i’ as the inverse of something (see also Dovey et al., 2021). I suggest this model can be useful in three main ways. The first lies in moving beyond dualist or binary thinking to better understand the ways in which co-production works between formal and informal modes of production (Koster and Nuijten, 2016). Second is a critique of power relations—the interrelations of the formal powers of the state with the empowerment of citizens. Finally, such an approach opens up ways of seeing urban informality-in-itself as more than derivative of the formal.

Beyond binaries

The dangers of binary thinking were highlighted in the earliest critiques of the urban informality framework (Bromley, 1978), particularly the tendency to gloss over the linkages between informal and formal (Peattie, 1987). Calls to move beyond binary thinking or to abandon the language of informality entirely have become frequent in urban studies (McFarlane and Waibel, 2012; Varley, 2013; Chiodelli and Moroni, 2014; Koster and Nuijten, 2016; Recio et al., 2017; Marx and Kelling, 2019; Banks et al., 2020). It is now well understood that labels such as ‘informal trading’ and ‘informal settlement’ are relative terms—we are generally looking at complex intersections of formal/informal processes and practices. Yet if informality cannot be simply identified with illegality, if so many agents operate across the formal/informal divide, and if urban development processes and outcomes are inevitably both formal and informal, then what is the usefulness of the framework? Herrle and Fokdal (2011: 8) argue that the concept of informality ‘almost inevitably re-establishes a dichotomy that so many observers claim to have overcome’, suggesting we focus instead on concepts like ‘power’, ‘legitimacy’ and ‘resources’. But are these terms less problematic, and are they not precisely what is at stake within the informal/formal framework? Caldeira (2017) suggests we replace the informality framework with a conception of ‘peripheral' urbanism, but this largely substitutes centre/periphery for formal/informal. We can rename the informal as ‘ordinary’ (Robinson, 2006), ‘marginal’ (Lancione, 2016), ‘peripheral’ (Caldeira, 2017), or ‘popular’ (Simone, 2019; Streule et al., 2020), each of which adds a different perspective and another potentional binary without shifting the field. If we are to better understand different modes of production that are interlinked in complex ways, then the challenge is to enter into these complexities rather than change the label.

Marx and Kelling (2019) suggest a move beyond binary thinking by examining the ‘common denominators’ which connect informal and formal, such as property rights and urban aesthetics. This approach has some affinities with the seven i's approach outlined above: property rights involve the illegality and insecurity of tenure; the aesthetics of informality is geared to irregularity and incrementality of form. However, all such attempts to cut through or move beyond binary thinking tend to leave the ‘formal’ in place as the privileged term that frames the informal in opposition. Thus the problem is not just the binary structure of the formal/informal distinction, it is also that it embodies an asymmetry or hierarchy. Linguistic theory would suggest that this is an ‘unmarked/marked’ distinction where the ‘unmarked’ term (formal) is the default that establishes the frame within which the ‘marked’ term (informal) is defined (Battistella, 1996). Urban informality is marked for attention within the valorized field of the formal city. The language of urban ‘informality' embodies an implicit assumption that the ‘formal' comes first and the in-formal emerges as a deviation or difference from a formal code. There have long been suggestions to rethink this notion of the formal as the norm and the informal as deviation (McFarlane and Waibel, 2012; Harris, 2018; Acuto et al., 2019; Iveson et al., 2019; Pratt, 2019), yet steps in this direction have been tentative. Scott argues that the formal city is often parasitic on the informal without which it cannot effectively function (1998: 7). Watson (2009) suggests that ‘seeing from the South' is to understand the informal as normal. Marx (2009: 337–40) has argued that framing informality as simply other to the formal framework can limit our understanding of how urban informality works in terms of power and agency.

So how might we understand urban informality-in-itself rather than as other to the formal? I suggest an inversion with the informal as the ground upon which the formal is built. Urban informality cannot be reduced to the inverse of the formal, because the informal is the original or ur-form of urbanity. Such an inversion requires an ontology that does not implicitly privilege the formal as the framework. Assemblage thinking embodies a flat ontology, derived originally from Spinoza, wherein identities emerge from a relational field of differences; difference-in-itself is a concept that is not subordinated to a pre-existing order of ‘things’. What we think of as things or identities emerge from networks of interrelations (Deleuze and Guattari, 1987; DeLanda, 2006; Dovey, 2010). From this view, a city is an intensive node of interconnected flows from which place identity emerges. These interrelations are informal first and become formalized, codified, regulated, stabilized and territorialized. Within assemblage thinking we find many twofold and non-binary concepts that resonate strongly with each other and with the informal/formal framework; these include rhizome/tree, smooth/striated, supple/rigid, difference/identity and becoming/being (Deleuze and Guattari, 1987). In each case, these are conceptual windows onto the ways hierarchic thinking brings order and stability to a world of networks and flows, the ways territories and identities are constructed and stabilized from a world of differences. Practices of power operate top-down, bottom-up, and laterally. Rather than reducing informality to a strict definition, assemblage thinking invites engagement with its ambiguities. The seven i's model elaborated above derives from such an approach as a lens to understand how informal/formal urbanism works. It could be argued that placing the informal as the ground upon which the formal is constructed would be falling back into binary thinking. Yet this approach is not only a way of rethinking urban informality, but the concept of urbanity itself.

Urbanity

Wirth's seminal article ‘Urbanism as a way of life’ (1938) defines urbanity primarily in terms of density and social heterogeneity—a socio-spatial condition of sustained intensive encounter with strangers. The term ‘urban’ (L: urbanus) is linked to the idea of ‘courtesy’—urban space is shared with people we do not know nor necessarily agree with; to be urban is to respect difference. The ‘city’ (L: civitas) is also linked to the concept of civility, and through the Greek word polis we find a similar connection to ‘politeness’ and the idea that the city may need more formal ‘policy’ and ‘police’. The formal codes of the city develop in order to sustain a more informal urbanity. The economic value of intensive but informal face-to-face interaction with strangers has been recognized ever since Marshall (1890) suggested that ‘something in the air’ was at the heart of how urban industry clusters work; more recently understood as an economics of agglomeration and urban buzz (Storper and Venables, 2004). For Jacobs (1961) the productivity of cities lies in a set of synergies between density, functional mix, and access networks that sustain intensive street life. The central idea of Sennett's (1994) urbanism is the random encounter with difference. These are all fundamentally informal processes that can be distinguished from the formal governance structures that frame them. In all of these ways the informal precedes the formal which emerges to sustain and control the informal. How then does this idea of informality-in-itself mesh with the reality that the formal and informal are everywhere intermeshed? I now want to further illustrate and interrogate these arguments and interrelations by looking at examples from three primary modes of informal production: informal settlement, street vending and informal transport.

Informal settlement

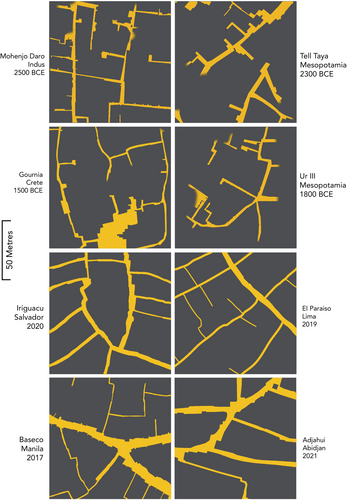

It has long been noted that informal settlements have a good deal in common with the traditional village and the medieval city which share an urban morphology produced by self-organized adaptation over time. The urban morphologies of traditional Mediterranean settlements are based on codes that were originally informal (Hakim, 2014). While the archaeology of pre-modern cities has long concentrated on the formal structures of state power—temples, palaces, plazas and monuments—excavations of ordinary neighbourhoods mostly reveal an informal morphology that has a longer history in the proto-cities and large villages of the neolithic era, several millennia before the establishment of the earliest city-states (Matney, 2002; During, 2005). Figure 2 compares the street networks of a range of neighbourhoods in ancient cities and towns with those in contemporary informal settlements at the same one-hectare scale. While this is not the place for a detailed comparative critique, the evidence suggests highly similar morphogenic processes. This form of urbanism developed over the period of the rise of the state, but its earliest examples preceded the formation of states by several millennia. Informal urbanism is modified by the state, but does not originate in state formation.

The distinction between so-called ‘planned’ versus ‘unplanned’ patterns of urban growth has long been a staple of urban history, with the latter identified by an ‘organic’ morphology of irregular, crooked streets. Kostof (1991: 43), for instance, shows how highly formalized cities can become informalized over time, and vice versa. Smith (2009) shows how ancient cities were rarely formalized beyond their ceremonial centres. Informal settlements are not ‘unplanned’ but embody a spatial logic with a self-organized assemblage of buildings, blocks, streets and lanes that enables walkable access with rights of way to every property (Dovey et al., 2023). These are morphologies that enable urban life to take place under conditions of high density and heterogeneity. Labels like ‘unplanned’ and ‘organic’ stand in for our lack of knowledge about how informal urbanism works and becomes entangled with formal structures.

Street markets

I now want to consider a second way in which these entanglements occur. Street markets, where people trade face-to-face in public space, are the earliest form of markets with a central role in the emergence of cities. The proliferation of street vending as a key form of informal urbanism is not an archaic remnant but geared to the ur-form of markets. Braudel (1979) makes a crucial distinction between a market as a zone of economic activity and capitalism as the organized extraction of profit from markets. For Braudel, markets are defined by competition and transparency, where production and exchange are insinuated into the everyday life that is sustained (Wallerstein, 1991). Capitalism is distinguished from markets by higher levels of organization, larger capital flows, and organized labour. For Braudel capitalism is ‘anti-market’ in the sense that it seeks to destroy competition through monopolistic control. Another way to put this distinction is that markets are self-organized while capitalism is hierarchic—markets are informal networks which capitalism formalizes into tree-like hierarchies. In this sense, neoliberal capitalism is organized to extract profit from informal production; it is a colonization of markets. The city is a marketplace of ideas, buildings, materials, land, products and jobs; urban informality is based in these self-organized markets and practiced within the tensions between markets and capitalism. This is the same paradox—markets are productive yet need formal controls. Braudel's distinction between markets and capitalism is crucial to avoiding any reduction of informality to capitalism. Capitalism is, of course, market-based, but the conflation of market with capitalism is ideological because it constructs all regulation as a constraint on freedom. Informal vending is the earliest form of markets, preceding cities, streets and shops which emerge and are shaped to enable markets to flourish.

Informal transport

Finally, consider the way we tend to limit the definition of ‘informal transport’ to self-organized rickshaws, motorcycle taxis, and so on. Yet ‘walking’ is the ur-form of urban mobility—the mode of access to the other modes; it is also the basis of face-to-face encounter in public space, and the ground of urban culture (Ingold, 2004). Walking is fundamentally informal; highly adaptive micro-scale practices, such as the ‘twist-and-slide’ through which we avoid collisions with strangers in crowded streets, are self-organized and cannot be formalized. At the same time walking becomes enmeshed with all kinds of formal codes and access protocols. To say that walking is the ur-form of mobility does not deny the importance of these controls, but these informal/formal relations are not symmetric. Formalized modes of transport from cars to planes are all based on walkable access. A great deal of urban research is now focused on a capacity labelled ‘walkability’, which is geared in turn to environmental, health, social equity and productivity outcomes (Dovey and Pafka, 2020). Understanding urban walkability is a highly complex challenge that requires us to see walking as much more than the inverse of formal transport. This surge in research on the ‘walkability’ of cities is partly due to the consequences of taking walking for granted as we planned and designed the car-dependent city of the twentieth century. All forms of vehicular transport are supplements to walking, producing dangers that require formalization.

The inversion of the informal to become the ground of the formal enables us to re-think the full range of modes of informal/formal urbanism. This is a view of informal settlement as a mode of production of affordable housing and infrastructure that only becomes ‘other’ to the formal once cities are formalized, and when such settlement is stimulated by economic inequalities and neoliberal economies. To understand street vending as the ur-form of markets is to re-think the relations between streets and vending—street vending was the earliest form of shopping; streets were shaped to enable and to formalize vending. This inversion also enables us to stop taking walking for granted and conflating public transport with formalized mobility, to see walking as the ur-form, which other modes accelerate while remaining dependent. In a broader frame, it also enables us to understand the informal as normal, and to see that it is within the interrelations between these modes of settlement, street vending, and transport that the deep resilience of urban informality can be found (Dovey and Recio, 2024).

Keeping the ur- in urban studies

I want to conclude with a brief summary and highlight some key issues at stake. Despite the difficulties of defining or operationalizing the concept of informal urbanism, and many calls to move ‘beyond informality’, it continues to expand as a research theme. I have presented informal urbanism as a paradox that can be understood as both produced by neoliberal capitalism and as embodying the right to the city. Informality is clearly more than a lack of formality; the semantic inversion suggested here is to understand the informal as the ground of the formal city—the original or ur-form of urbanism. Informalities are not just practices that we can identify within cities, rather they are immanent to the modes of production that give rise to cities, and that may or may not be formalized in different ways and degrees. This is a framework that enables us to describe and analyse how cities work in terms of both bottom-up and top-down organization, networks and hierarchies.

The idea of informality as the ground of the formal has long had parallels in social theory where informal social interaction is crucial for the development of trust, yet formal rules emerge from the need for agreed standards of security and transparency (Crozier and Friedman, 1980; Misztal, 2000). Formal rules are legitimated on the logic of protecting the rights of citizens, but they also place limits on self-organization, productivity, creativity and adaptability. One of the traps of binary thinking is to ask whether the informal or formal is good or bad. As Tonkiss (2013: 112) puts it: ‘the relationship of formality to informality in cities is not an either/or, but a question of how to handle the mix’. This is no simple question of finding a balance, but of engaging with the paradox of urban informality, to better understand how both formal and informal are related to questions of equity, oppression, productivity, adaptability and freedom. The crucial difference is not between informal and formal practices and places, but between those where they are in productive synergy, and those where one or the other dominates. The often over-informalized cities and neighbourhoods of the global South can be counterposed with the often over-formalized cities of the global North where temporary/tactical urbanism has become a crucial means of increasing the agility, accessibility and vitality of public space (Stevens and Dovey, 2022).

I have argued that an assemblage ontology enables us to rethink the paradox of urban informality. The question of whether such an approach is useful will surely continue, but this article is not about assemblage thinking. The world of ideas is geared to a world of practice wherein ideas are implemented, for better or worse. The key concern is that ideas and concepts should be useful—do they enable us to rethink how cities work, how they stabilize, and how they might change? What is most at stake here are the livelihoods of billions of relatively impoverished people engaged in urban informality as a primary mode of production. While there are many informalities in cities of the global North, it is global South cities where livelihoods are most deeply informalized. To understand urban informality as a mode of production is also to understand that the productivity of the city is at stake. Urban informality is at the heart of what makes a city tick. Informal urbanism produces the bulk of the world's affordable housing and a huge proportion of retail production and public transport. Urban informality is also a form of power that is held by the urban poor. To use Lister's (2021) terms, informality is a means of ‘getting by’, perhaps ‘getting out’ of poverty, a means of ‘getting back’ at a state that fails to ensure livelihoods and of ‘getting organized’. However, such recognition of the productivity, adaptability and potency of informal urbanism must not be an excuse for any romantic notion of the urban poor bootstrapping their way out of structural inequality. Nor is it a legitimation of neoliberal deregulation or elite corruption dressed up as informality.

The key research challenge is to develop a deeper and broader knowledge base about how informal urbanism works. This process entails going beyond both proclamations of the right to the city and critiques of neoliberal urbanism, accepting both such viewpoints and engaging with the paradox. There are many calls to develop comparative research that engages with multiple cities with different scales, sites and disciplinary lenses, and with critical attention to questions of power and spatial justice (Boanada-Fuchs and Boanada-Fuchs 2018; Acuto et al., 2019; Banks et al., 2020; Amin and Lancione, 2022; Dovey et al., 2023). Yet informal urbanism is more difficult to research than formal urbanism; the data is on the ground and often illegible, camouflaged or inaccessible. The knowledge of how informal urbanism works is informal knowledge (McFarlane and Waibel, 2012), well understood by many different actors on the street, but not by those who plan, design, and govern the city. Such knowledge can also be dangerous in the service of neoliberal planning regimes. With all their complexities, these are the cities that we have, they are not ideal but are not improved by having formal ideals imposed upon them.

To understand informality as the ur- form of urbanity suggests an inversion in ways of thinking about how cities change. Urban planning embodies a formal prejudice by definition—the discipline was invented to control undesirable outcomes of informal urban development. Urban life in the modern city cannot flourish without formal codes that protect citizens from the excesses of unregulated practices and markets. Yet informality is also fundamental to an equitable, vibrant, productive and resilient urbanity. The challenge is to learn how such practices are geared to livelihoods, productivity, creativity and resilience. It is to invent and negotiate frameworks and infrastructures within which urban informality can work better rather than being erased. Over-informalized neighbourhoods will inevitably become more formal, but the opposite may be the case in over-formalized neighbourhoods. In both cases, in the global South and North, the challenge is to rethink the relations of formal to informal—keeping the ur- in urban studies.

Biography

Kim Dovey, Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning, University of Melbourne, Victoria 3010, Australia, [email protected]