ELSEWHERES OF THE UNBUILT: The Global Effects of Transnational Energy Infrastructure Projects

We would like to thank the IJURR editorial team and reviewers for their helpful feedback and comments. All authors received EUCOR—The European Campus seed funding (‘Making Infrastructure Global? Design and Governance of Infrastructural Expansion in the global South’). Benjamin Schuetze also benefited from DFG funding (‘Renewable Energies, Renewed Authoritarianisms? The Political Economy of Solar Energy in the MENA’; SCHU 3487/1-1) and support from the Young Academy for Sustainability Research at the Freiburg Institute for Advanced Studies (FRIAS). Alke Jenss also received funding from the Thyssen Foundation (‘Promises of Democratic Connection?’; AZ 10.21.2.010PO). Open access funding provided by Universitat Basel.

Abstract

Pipelines and refineries, hydropower dams, and solar and wind power projects feeding into emerging transnational energy networks make up the thrust of a new push for infrastructural expansion in the global South. This article argues that understanding the effects of this expansion requires attending to the multiple elsewheres of transnational energy projects in various states of realization. By this we mean accounting for the ways in which these projects are financed, planned, contested, contracted, built, transformed and withheld at multiple, sometimes connected and sometimes disparate, sites across the globe. Focusing on the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP), the Central American Electric Interconnection System (SIEPAC) and the Mediterranean Electricity Ring (MedRing), our research shows that such projects are ‘global’ not only in their physical reach and forging of connections between disparate and expansive geographies, but also in the ways they bring into being new, transnational or global publics.

Introduction

A new generation of transnational energy infrastructure projects is currently underway. Across the global South, pipelines and refineries, hydropower dams, and solar and wind power projects are being built to feed into emerging transnational energy networks. These projects make up the thrust of infrastructural expansion in the global South. Shaped by a complex mix of authoritarian statecraft, Northern dominance, neoliberal policy and global finance, they are often accompanied by and catalyze the mobilization of transnational publics that contest these emerging energy infrastructures and their projected consequences. While some of these projects are shaped by global agendas of climate change adaptation, others remain obstinately rooted in fossil extractivism. Projects such as the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP), the Central American Electric Interconnection System (SIEPAC) and the Mediterranean Electricity Ring (MedRing), the empirical foci of this article, are key examples both of transnational infrastructure expansion and its contestation.1 Whether based on fossil or renewable energy, these megaprojects do not materialize from one day to the next, but emerge in long, contested processes that spatially and temporally transcend the sites of construction.

In various stages of (in)completion, these projects stand out for their transnational scope, not only in terms of the range of actors involved in their financing, contracting, planning and construction, but also in terms of how they are opposed, and sometimes successfully blocked or stalled. New crude oil pipelines in particular have prompted vivid protests and legal contestation, sometimes thousands of miles away from the places of their planned construction. Distributional energy projects, such as transnational electricity grids, have similarly triggered mobilization efforts that cannot be reduced to merely ‘local’ effects. Contestation against large-scale energy projects does not take place everywhere or anywhere, but does mobilize transregional networks and virtual forms of organizing in ways that expand geographic imaginations about where transnational infrastructure comes into being and is contested.2 This article thus asks how we can make sense of these emerging geographies of connection and contestation in assessing the global effects of transnational energy projects under construction.

Urban and regional studies scholars have conceptualized transnational energy projects as part of an emerging regime based on the regional deployment of ‘global infrastructure’. They have analyzed how these infrastructure projects spur processes of extended urbanization by linking resource frontiers to urban systems, often across national borders, and as such give rise to an ‘infrastructural regionalism’ (Glass et al., 2019). Seth Schindler and Miguel Kanai (2019) have argued that infrastructure deployment of this kind takes up older spatial planning strategies from the postwar era. Building on an analysis of previously failed energy megaprojects such as Desertec (Schmitt, 2018) and Atlantropa, which envisaged the merging of Africa and Europe by closing off the Mediterranean and triggering its evaporation with the help of massive dams, and their ‘technocratic regime of colonial exploitation’ (Cupers, 2024), a direct line can be drawn, for instance, to the MedRing project that we discuss in this article (see also Schuetze, 2023). Alan Wiig and Jonathan Silver (2019) suggest moving away from interpretations of such infrastructure as driven by and resulting in standardization across space and time, offering analytical tools for analyzing the various stages of deployment that characterize these transnational infrastructure projects.

Scholars of global politics have analyzed ongoing contestation against both fossil and renewable energy infrastructure projects within the same analytical field despite differences in their goals and responses. They emphasize the tension between these projects’ universalizing promises of connection and the asymmetrical power relations undergirding them (Khalili, 2020: 21; Björkman, 2015; van Veelen et al., 2021). Within these frictive spaces, contestation can emerge and, indeed, has emerged, particularly, but not only, with regard to oil infrastructures (Bridge et al., 2018; Bosworth, 2019; Van Neste, 2020) and hydropower (Ahlers, 2019; Hommes et al., 2022). Ávila et al. (2021) analyze the role of countermapping collectives in emerging geographies of renewable energy infrastructures. Susana Batel and Patrick Devine-Wright (2017) examine how energy technology developers ignore affected publics’ opposition to these infrastructures, framing this as energy colonialism. Catalina de Onís (2021: 25) explores the political agency inherent in ‘archipelagic collaborative ways of preexisting’ around malfunctioning energy infrastructures shaped by global power relations and informal empires. Charis Enns and Brock Bersaglio (2019) see transnational energy infrastructure projects as echoes of colonial-era development projects. Clemens Greiner et al., (2022) similarly analyze renewable energy infrastructure projects as part of new ‘resource frontiers’. Such projects frequently spur forms of indigenous dispossession, but also elicit creative responses by grassroots initiatives (such as reclaiming land or blocking infrastructure) (de Onís, 2021). This research aligns with a substantive body of scholarship on the role of infrastructure in reproducing colonial and imperial relations of power (Cowen, 2014; 2019; Chua et al., 2018; Ernstson and Kimari, 2020; Cupers et al., 2022; Curley, 2023). We draw on the above-mentioned accounts of contestation and agency in the face of large transnational infrastructure projects.

Despite the global scope of such scholarship, the contestation of such projects is often implicitly researched as local, that is, situated at the sites of construction. Focusing on the three transnational energy projects mentioned above, this article argues that, in order to assess the ongoing effects of these transnational energy projects in various states of realization, we need to attend to their multiple elsewheres, by which we mean to account for the ways in which these projects are financed, planned, contested, contracted, built, transformed and withheld at multiple, sometimes connected and sometimes disparate, sites across the globe. Such projects are ‘global’ not only in their physical reach and forging of connections between disparate and expansive geographies in how they are conceived and planned, but also in the ways these yet unbuilt infrastructures call into being transnational or global infrastructural publics (Collier et al., 2016). This article addresses the conceptual and methodological issues arising from both aspects of these projects’ globality.

The global nature of these publics is mirrored in appeals to the planetary scale of these projects’ environmental consequences and in the discursive emphasis on their relations to global projects of empire. To account for ways in which such global contests manifest across geographies, we argue, requires a broadening of analytical frames. We conceptualize this broadening as drawing attention to the ‘elsewheres’ of the unbuilt. Our approach to studying these elsewheres differs slightly from the analytical thrust of Jennifer Robinson's (2016; 2022) proposal to ‘think cities through elsewhere’. While thinking these transnational projects and their publics through each other is certainly a comparative gesture in Robinson's terms, we likewise use elsewhere to convey Massey's (1994) non-essentialist view of place. We use it, that is, to conceptualize the ‘place’ of infrastructure as made up of many different locations and to acknowledge contestatory politics around specific energy infrastructures that transcend the places and times of their construction. These politics of infrastructure beyond the places of their construction are an extension of Massey's (2007) argument about expanding responsibilities and relations across wider geographies.

In the following analysis, we cover three transnational energy projects in the global South as a way of approaching infrastructure through the specific elsewheres that are brought into their orbit by those promoting them and by acts of resistance and opposition. We do so in an effort to account for and analyze the material and virtual geographies implicated in infrastructural becoming and, potentially, infrastructural undoing. Through case-based considerations of the places in which these projects are contested, we seek to add new access points for trans-scalar analyses appropriate to studying the effects of transnational energy projects.

Our empirical research focuses on the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP), the Central American Electric Interconnection System (SIEPAC), and the Mediterranean Electricity Ring (MedRing). While SIEPAC had already been built, EACOP had not yet broken ground at the time of writing and MedRing exists more as an overarching vision connecting multiple, independent energy projects. This geographic range and diversity in terms of states of existence allow us to analyze the contingent effects of these different ‘energized practices’ (Rignall, 2016: 542). Depending on context, energy infrastructures can engineer and encompass a diverse set of socio-political relations (Mitchell, 2011)—ranging from acquiescence to open opposition and intransigence. Our research grapples with the multiple places through which energy megaprojects come into being (beyond where they are or will be built), as well as the multiple temporalities that coalesce in infrastructural deployment. This builds on scholarship focused on unbuilt and unfinished infrastructure as summarized by Ashley Carse and David Kneas (2019) and adds an emphasis on the effects and practices of protest engendered by projects before they are fully realized or materialized. As a result, our research expands infrastructural inquiry to political effects prior to completion and to forms of power exerted by transnational infrastructure, allowing us to explore the geographies, timelines and constitutions of publics that promote and/or contest these projects.

The article moves in two steps. First, we explore how transnational energy projects are produced in and through multiple elsewheres, both physical and virtual. We suggest that, in order to capture these infrastructural and contestatory elsewheres analytically, especially given the acceleration of digitization brought about by the pandemic, we should analyze different forms of agency asserted at and through both connected and disparate sites. It is because the infrastructure projects and publics are transnational and their impact on social relations reaches beyond materialized, built infrastructures, that we need to move beyond a localizable ‘field’, conceptually and methodologically. We make this move recognizing the methodological tradition in global ethnography of ‘following the thing’ (Marcus, 1995; Shamir, 2013: 11; Tsing, 2015), adapted by Deborah Cowen (2019) to ‘following the infrastructure’. By invoking Cowen's gesture of following infrastructure across history and struggle, we recover relations of power that constitute and are created by ‘heterogenous infrastructural configurations’ deployed transnationally (Lawhon et al., 2018; Silvast and Virtanen, 2019). In fact, pandemic-induced travel restrictions influenced initial methodological decisions but also pushed the promotion and contestation of these projects increasingly into the digital sphere during the research period, prompting us, as researchers, to follow how these infrastructure projects became ‘issues being done in networks’ and across geographies (Marres and Rodgers, 2005: 922). Beyond digital research, our argument equally draws upon empirical research (interviews, observations, archival work) in Morocco, Costa Rica and Tanzania in 2022 and 2023.3 Second, we explore the transnational counterpublics of transnational energy infrastructure projects, emerging before, during, and after various materializations. Our claim lies in the fact that these contestatory publics emerge not only at the site of construction, but also at sites where infrastructures are planned, at global scales, and at places not directly impacted by the projects’ (potential) materiality. This argument is both conceptual and methodological: to trace the constitution and claims of transnational infrastructure publics requires relying on complementary digital research sites beyond those in the built environment.

Global geographies of energy infrastructures

Efforts to bring more expansive geographies and temporalities into the study of infrastructure rely on a relational approach that recognizes the ways that infrastructures connect and condense translocal social relations at a specific site. As mentioned above, understanding infrastructures themselves as association or connection, or as ‘object and method of inquiry’ has given birth to methodologies that ‘follow the infrastructure’ from a bank archive in London to railway tracks (Cowen, 2019) or ‘follow the wires’ (Shamir, 2013).

Our research targeted project parts and wholes that are not (and might never be) fully built, problematizing the type and mode of ‘following’ that has been promulgated in recent social science studies of infrastructure. For instance, while SIEPAC has been operating since 2014, it is embedded in the larger Mesoamerican Project, a continental infrastructural endeavor in varying stages of planning or completion since the 1990s. Moreover, while the SIEPAC grid has already been built, we might think of it as perpetually unfinished in ‘infrastructural time’, taking into account still planned interconnections and unsatisfactory promises of futurity (Appel, 2019). EACOP is similarly part of a wider Lake Albert Resources Development Project that seeks to develop two oil field areas (Kingfisher and Tilenga) in western Uganda with EACOP serving as the midstream infrastructure, if it is ever built. MedRing, on the other hand, is the larger, wider project for an interconnected electricity ring circling and crossing the Mediterranean and linking the EU, North Africa and the Middle East in order to facilitate greater integration of variable and intermittent renewable energies. It is a vision or articulation of an infrastructural totality, comprising separate electricity blocks seeking synchronous interconnection.

Recognizing the (in)completion, openness and contingent nature of these three projects, we depart from more familiar stories of ‘following’ to propose following the power relations implicated in the built and unbuilt. Who decides about, owns, and shapes the future form of energy infrastructures? Who, in specific places around (future) construction sites, is empowered and can exercise some form of authority? Instead of making different sites the condition for research, following the power relations around infrastructure planning, we arrive at different sites and moments in time as a result. Connecting anthropological and political economy approaches, we stress the inherently relational aspect to this approach, which allows us to overcome one-sided perspectives and include critiques such as the romanticization of the ‘local’ (see Shamir, 2013; Harvey and Knox, 2015). Taken together, these projects equally emphasize that infrastructural power relations are not finite or stable, but constantly becoming in ways that keep ‘modes of existence open to improvisation’ (Biehl and Locke, 2017: x). The openness of their existence is not only a temporal consideration but extends to the global range of cartographies, geographies, and sites through which SIEPAC, EACOP, and MedRing come into being. In the paragraphs that follow, we offer descriptions of the three megaprojects that foreground the ‘nonlinear space-time and the extensive, contingent itineraries’ of their becoming (ibid.: 8). The project introductions that follow particularly hone in on the places implicated in these projects even before they take material shape on site.

EACOP

The East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP) (see Figure 1) is planned as the world's longest, electrically heated crude oil pipeline, running 1,443 kilometers from Hoima, Uganda to Chongoleani, Tanzania. The pipeline project shareholders include the French-headquartered multinational energy company Total Energies (68%), China National Offshore Oil Company (CNOOC) (8%), the Uganda National Oil Company (UNOC) (15%) and the Tanzania Petroleum Development Corporation (TPDC) (15%). A dizzying array of firms, consultants and consortia have been involved in the pipeline planning process to date, from worldwide operators such as Gulf Companies (USA), Worley Parsons (Australia), and Schneider Electric (France), to boutique firms and individual subcontractors from the Ugandan and Tanzanian consulting industry and academia. The proliferation of companies and entities involved thus far has much to do with the differences between the legal and commercial frameworks that regulate national content in Uganda and local content in Tanzania and dynamic, ‘urgent’ changes to these frameworks in the late 2010s (Barlow, 2020). It was anticipated that the pipeline would be completed in 2020, a forecast that has repeatedly been pushed over the last several years with a Final Investment Decision only being made in February 2022. While the financing arrangement for the estimated five-billion-US dollar project budget remains unclear and incomplete to date, advisors charged with raising debt financing have included Stanbic (a Ugandan subsidiary of the South African Standard Bank) and Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation (Japan) (Banktrack, 2020).

What is equally uncertain at this stage is where the material matter for this energy infrastructure will come from. In a Ugandan television appearance in November 2021, EACOP General Manager Martin Tiffen mentioned engaging between four and five steel mills around the world to produce the 270,000 tons of steel pipe required for the project (Next Media Uganda, 2021). Tiffen charted the course of the steel pipes (yet to be acquired) across the ocean to the port of Dar es Salaam since the magnitude of the order is beyond the capacity of any single steel manufacturer (and presumably any plant on the African continent). From the port, the pipes travel to a coating yard in Nzega and on to one of 16 Main Camp and Pipe Yards from which they will be placed in the ground along the determined route. The route follows parts of the Central Development Corridor, a crucial component of Tanzania's current national development plan—Vision 2025. The Central Corridor corresponds to historic East African and Zanzibari trade routes of the 1800s and today forms part of a larger Maritime Silk Road scheme under China's Belt and Road Initiative (Enns and Bersaglio, 2019; Wiig and Silver, 2019).

SIEPAC

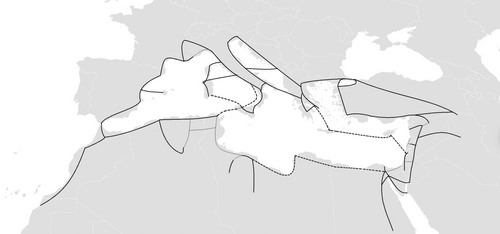

SIEPAC, the Central American Electrical Interconnection System (see Figure 2), is a 1,830 km single-circuit electricity grid between Panama and the Guatemalan border with Mexico that aims to scale up unhindered energy flows, power generation and sharing. SIEPAC is a crucial component of the wider Mesoamerican Project, a transnational umbrella for infrastructure that projects ports, roads and energy infrastructures into a prosperous future. An interconnector that would integrate the Panamanian and Colombian grids has been projected since 2008. The Panamanian government suspended it in 2012, but Interconexión Eléctrica Colombia-Panamá (ICP), a joint corporate venture between electricity providers ETESA (Panama) and ISA (Colombia) entered a renewed planning cycle in 2019 (Global Transmission Report, 2021). As of early 2024, however, the superhighways, container ports, power plants and telecommunications networks that the Mesoamerican Project entails, remain partly unbuilt and contested.

Map of the SIEPAC project (produced by the authors) [Correction added on 27 September 2024, after first online publication:The figure notes have been removed in this version.]

Central American Governments and the Interamerican Development Bank planned SIEPAC as the material manifestation of the Regional Electricity Market (MER), established first and foremost through the gradual privatization of Central American electricity sectors in the 1990s (Geocomunes and Luxemburg Foundation, 2019: 9). The MER, however, needed a material transnational transmission infrastructure to deliver on the promise of broad electricity access and competition. Funders project this joint energy market as a condition for prosperity and response to energy crises, criticizing governments for delays in harmonizing their legislation (OECD, 2017). Governments, in turn, have long applauded a joint energy market, yet in 2021 the Guatemalan state resigned from the MER that SIEPAC's materiality enabled, rejecting the payment conditions that transnational electricity flows implied (El Economista, 2021).

SIEPAC was not just financed or built in the global South. While the Interamerican Development Bank (IADB) and the Central American Bank for Economic Integration (CABEI) were fundamental for funding, the latter was only able to play that role thanks to a decisive loan by the German development bank KfW to start SIEPAC's construction (Global Transmission Report, 2021). Mexican Bank Bancomext and the Development Bank of Latin America (Corporacion Andina de Fomento CAF) provided loans, as did the EU's European Investment Bank headquartered in Luxembourg (ARIE, 2011). Capital is backed by the private shareholders of SIEPAC's operating entity EPR, such as the Spanish energy giant Endesa, Colombian ISA, and Mexican electricity provider CFE (semi-privatized through Mexico's 2013 energy law). SIEPAC's manufacturing sites include Aarhus, where the headquarters of wind energy giant Vestas are located, which provides turbines for platforms in Mexico and Central America, as well as Seville, where Abengoa energy engineers are based, who won the construction bid for the transmission line in Nicaragua, Costa Rica and Panama (ICIM, 2011). SIEPAC stretches to Montréal, given that Canadian engineering firm Dessau International (2013) devised a project management system for the construction phase.

MEDRING

The project for a Mediterranean electricity ring (see Figure 3) envisages the reinforcement of existing interconnectors (for example between Morocco and Spain) and the construction of new ones (for example between Tunisia and Italy), to link European and North African grids into one interconnected supergrid. In doing so, it draws on the idea behind past failed megaprojects such as Desertec (Schmitt, 2018), which had envisaged the large-scale production of solar power plants in the MENA region and the partial export of the electricity thus produced to Europe. The ring remains incomplete and partly unbuilt, and a number of existing interconnectors are non-operational or underused. A 2010 synchronization test for the Tunisia–Libya interconnector failed and Jordan and Syria agreed only in 2021 to reoperationalize an interconnection that has been out of service since 2012. Besides inadequate interconnections on the southern shore of the Mediterranean, existing linkages on the European side, in particular between Spain and France, are insufficient for large-scale transnational electricity exchanges, with various reinforcement projects planned and/or ongoing. European policymakers present the project as helping the EU to meet its energy demand with alternative renewable sources, particularly solar and wind energy. Accordingly, the EU views planned interconnectors crossing and/or circling the Mediterranean as ‘Priority Projects of European Interest’ (EC, 2003). This enables accelerated planning and permit granting, and access to a total budget of € 5.35 billion from the EU's Connecting Europe Facility (CEF).

Map of MedRing idea/project. Schematic illustration of select high-voltage transmission lines crossing and/or circling the Mediterranean (source: based on information available at www.entsoe.eu/data/map, adapted by the authors)

note: Only key lines >300 kV (in bold), < 300 kV (non-bold) are shown; existing connections in continuous lines, planned projects in dotted lines.

Descriptions of new routes for electricity exchange across the Mediterranean as ‘essential for energy security in the region’ (Global Transmission Report, 2009) see the project as enabling energy security for countries on its southern shore, and as enabling energy diversification for those in Europe. Besides existing ‘actual connections’, such as submarine electricity cables between Spain and Morocco, we must also explore what Robinson (2022: 129) calls ‘conceptual leaps’, namely proximities and links that different actors invent. Despite descriptions of mutual interest, the project idea behind MedRing and concrete interconnection projects are primarily driven and funded by the EU, European states and industrial initiatives such as MedGrid, which is heavily dominated by European companies. European policymakers not only portray greater electricity integration as a means to ensure (European) energy security and easier integration of renewables, but as opening the doors to a ‘common energy future’ (MEDREG, 2022), which they deem achievable via the empowerment of technocratic actors (Mediterranean regulators) and describe as reinforcing wider economic regional development. EU policymakers speak of ‘future electricity highways’, and technical analyses required ‘for the closure of the Mediterranean Electricity Ring …, currently broken or interrupted in several places’ (Duhamel and Beaussant, 2011: 18, 21).

It is not only the electricity cables themselves that, by circling and/or crossing the Mediterranean Sea, connect otherwise unconnected places, and the production sites of said cables. The 30km-long self-contained, oil-filled submarine cables between Fardioua in Morocco and Tarifa in Spain were, for instance, constructed by Nexans in Halden, Norway and by Pirelli in Naples, Italy and involved supranational actors including the European Commission, the European Investment Bank (EIB) and the Africa Development Bank (AFDB).

As these descriptions illustrate, the EACOP, SIEPAC and MedRing projects not only ‘take place’ between Panama and the Guatemalan border with Mexico, between Lake Albert and the Indian Ocean coast, and around the Mediterranean, but where pipes and (submarine) cables, as well as wind turbines and solar panels are planned, funded and manufactured, later to be connected to the wider infrastructural vision and network. The global expanse of these yet-to-be built or completed megaprojects, in their multiple geographies and temporalities, present the researcher with a vast range of sites where the effects of these ongoing projects can be explored. In addition, the ability of COVID-19 pandemic to alter infrastructural time and place as well as the time and place of infrastructural research cannot be underestimated. If energy projects materialize not only at construction sites, if arrival at these sites is not always possible, and if infrastructures remain unbuilt (Carse and Kneas, 2019), there may be other places to look—other sites and modes of infrastructural becoming and dissolution—that shed light on the power relations of which they are a part.

Spatializing infrastructural publics

Connecting our attunement to infrastructural becoming to the ways in which these infrastructures call publics into being (Collier et al., 2016), this section focuses on contestatory and aspirational publics that emerge before, during and after transnational energy infrastructure materializes, and on where and how these emerge. Publics located ‘elsewhere’ than at the (envisaged) site of construction may at times have more scope to contest than local ones, particularly if they are linked with global social activism that has decades of experience, such as the global environmental and international human rights movements.4 Contestatory publics that critique even the most global pressures and inequalities exerted through these energy projects nonetheless frequently connect and evidence their claims to more local, territorial and social impacts (what Massey (2007: 191) might call different ‘geographies of commitment’).

At the level of the nation-state, the relationship between infrastructures as providing services and extending citizenship based on an idea of belonging is not a given; it may even obscure those ‘histories’ that ‘escape inherently liberal conceptualizations of state–society relations and a discourse of rights to citizenship’ (Lesutis, 2022, 2). State-sanctioned promises of infrastructural expansion often stand in stark contrast to alternatives offered by civil society organizations, which are generally relegated to the margins of infrastructure planning (Hecht, 2011). Authors have pointed out how contestation emerges or increases as a result of being bypassed by a particular network (Anand et al., 2018) or out of disputes between documentation and realities on the ground (Barry, 2013).

The varied agency of different people engaging with planned infrastructures is core to our understanding of these contestatory publics. We use this term to account for the widest possible range of oppositional tactics, points of protest and coalitions of actors. We understand the contestatory publics as infrastructure actors (see also energy actors as described by de Onís, 2021) as much as the planning agencies. The former work across transregional spaces, because of the transregional scope of the projects, but contestation also takes place at locations that will never be directly impacted by the materiality of the projects. What makes these cases so interesting is that, as the projects are transnational, coalitions that have built up counterexpertise (Bosworth, 2018), create their own imaginaries (Hommes et al., 2022; Van Neste, 2019) and maps (Ávila et al., 2021), produce counterinfrastructures (Dajani and Mason, 2018) or have extended arenas for their claims (van Veelen et al., 2021) have also been largely transnational.

In sum, the agents and moments of contestation need not be localizable, but are co-constituted between local- and global-issue publics. The virtual elsewheres that we propose to add to the spatial practices of researchers studying unfinished and multisited infrastructure projects emerge, in all three cases, from the fact that coalitions among protestors, but also informational events by the planners themselves, took place digitally and drew people from diverse locations together into one infrastructural public. Contestation, therefore, occurs not just at the site of construction, but also at sites where infrastructures are planned and on global scales; it requires transregional efforts to organize, particularly if the agency of some is more easily visible to media and government actors than others. Simultaneously, while we cannot expand on this, the temporality of protest and projects is relevant; the pace of organizing across localities may differ from offline protests at a single site, and offline activism may be delayed by detentions or legal proceedings. Contestation may disrupt accelerated construction rhythms and pause the violence of some infrastructure projects (see Hetherington, 2014; Jenss, 2021). As others have already highlighted, opposition to energy infrastructure increasingly coalesces around issues of participation in decision making, socio-environmental impacts of the built development, and the power relations and global implications or legacies that these projects articulate (Bridge et al., 2018: 2; see also Massey, 2007).

The existence of contestatory publics is deeply context-dependent. In the particular case of EACOP, one of its most negative impacts, as cited by pipeline opponents, is planetary in scale and connects the burning of the fossil fuels carried by the pipeline to threats to the habitability of the earth. As the cases of MedRing and SIEPAC illustrate, transnationally connected infrastructure actors also contest ‘cleaner’ energy infrastructures, while the projects may redirect their opposition elsewhere. Contestatory publics gathered by MedRing and SIEPAC have leveraged discourses around the coloniality of stakeholder relations and their violent histories. Many Sahrawi protestors, for instance, see renewable energy plants that are located in Western Sahara and connect to the Moroccan grid—and thus to the envisaged MedRing—as directly reinforcing Moroccan colonialism and occupation, speaking of one ‘energopolitical regime’ (Allan et al., 2021: 9–10) that consists of both the Moroccan regime, and transnational corporations like Siemens and EDF. Publics contesting SIEPAC have perceived the transnationality of the project as a colonial ‘threat to territory’ (Foro Mesoamericano, 2011). Transnational alliances such as the Mesoamerican Forum and other movements understand the threat of displacement and dispossession as a reproduction of earlier incursions by actors located ‘elsewhere’, and the environmental degradation as active destruction from outside. While EACOP has provoked environmental organizations to speak of oil colonialism or corporate colonialism, appeals to the coloniality of the project have primarily come from global, Euro-American-based organizations, while many Ugandan and Tanzanian organizations center their critiques around their respective state politicians and politics of energy sovereignty (Jacob and Pedersen, 2018).

Following unequal power dynamics across times and scales, our research shows how emerging publics follow and mirror the infrastructure projects’ transnational dimensions and spatialize alongside them. Apart from actual construction sites, contestatory and aspirational publics (also) organize, at least sporadically, in social forums and via transnational networks that exchange ideas and/or modes of protest. Just as scholars of contemporary war explore new virtual battlespaces (Der Derian, 2009), and scholars of militarism analyze social networking as an instrument of warfare (Kuntsman and Stein, 2015), scholars of infrastructure can avail themselves not just of digital infrastructures per se, but online forms of presenting and contesting the material and the unbuilt. While social research has long made use of digital platforms and mediated methods, social scientists working in the interdisciplinary topic area of infrastructure have yet to fully acknowledge the methodological possibilities that digital archives offer. This is all the more pressing in a context in which actors and stakeholders involved in transnational infrastructure projects (and their contestation) turn to and leverage new and existing digital technologies to communicate, inform and interact with different publics.

EACOP

One space where the planned pipeline is simultaneously developed and contested is through virtual webinars hosted by investment platforms and EACOP itself. This space engenders infrastructural publics within and across national borders. Webinar panelists promote dominant discourses of economic development alongside questions and concerns among those seeking to seize the economic benefits as contractors providing what the industry calls national or local content. Because of the nature of the cyberplace created by the keyword or tag ‘EACOP’, supplier info sessions and initiatives hosted by project boosters exist in the same catalog as NGO workshops, short campaign videos and live streams of protests that oppose the project in terms of its social, environmental and climate risks. Cyberplaces that connect real people and organizations from across the globe hold in an analytically productive proximity the discursive, documentary and visual framings of infrastructure projects’ impacts understood in both developmental and destructive ways.

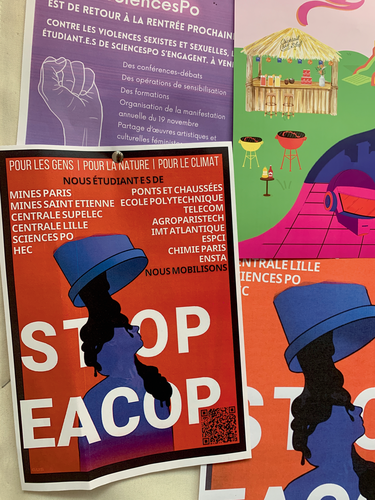

Due to the disastrous effects of fossil fuels on the planet, physical and virtual sites, stages and platforms across the world are being leveraged to mount public resistance to the East African Crude Oil Pipeline—bringing to life a ‘politics of place beyond place’ while equally enacting climate politics that encompass all places on the planet (Massey, 2007). Opposition has been geographically widespread and has included Extinction Rebellion protests in front of Standard Bank branches in Cape Town and Johannesburg, disruptions at the African Energy Summit in London and NGO-spearheaded lawsuits in French courtrooms. Across various cyber places, circulating hashtags and webinars regroup environmental activists, religious movements, and organizations that target financial institutions in global cities contributing to the production of the infrastructure itself as well as its potential impacts at varying scales. The largest of such alliances, the #STOPEACOP movement (see Figure 4), has focused its efforts on pressuring financial institutions not to finance or insure the loans required to pay for the pipeline. The #STOPEACOP campaign distinguishes this tactic as ‘Go[ing] Global’, working to sever financial capital from its role as a ‘key determinant of the climate system on earth’ (Mbembe, 2021: 15). Such activism must necessarily engage with the global geography of the lending market due to the magnitude of investment required. Compared to other internationally recognized pipeline opposition movements such as #NoDAPL, #STOPEACOP did not manifest first in places along the pipeline's path before ‘going global’ but rather began as a transnational alliance, pressuring banks and insurers around the world (as #NoDAPL did in later phases of the movement) to divest from the pipeline.

Notably marginal in this geography of activism and resistance are Uganda and Tanzania, the two countries through which EACOP will run. An EACOP manager based in Dar es Salaam was particularly keen to point out that the project has provoked limited opposition in Tanzania, calling the situation ‘very quiet’ (Personal Communication, June 17, 2022). This hushedness, however, is rooted in several affective states and political stakes. Emmanuel (pseudonym), who works at one of the oldest environmental NGOs in Tanzania, explained their limited involvement with EACOP as one that is entangled with fear born out of legacies of the late president, John Magufuli. The stipulations of various pieces of legislation and the politics of the current regime make speaking out a risk to an NGO's existence, while histories of violent repression of the opposition and critical voices make the risk of arrest, disappearance or death real to Emmanuel and his team (Personal Communication, June 17, 2022). In many ways the magnitude of the project, the benefits that the government has promised, and its continued promotion of resource nationalism (Jacob and Pedersen, 2018) heighten both the stakes of EACOP for the ruling regime and the fear of speaking out against it by civil society. In neighboring Uganda, the risks perceived by Emmanuel have become a reality, as two anti-EACOP activists were met with detention and attempted burglary on returning from a court hearing in France as part of a lawsuit against Total. The global nature of opposition to EACOP therefore needs to be understood in terms of the context-specific politics and constraints on organizations and activists in the countries hosting the pipeline, as well as a decades-long history of transnational alliance building among environmental organizations to lower greenhouse gas emissions by ending fossil fuel financing.

SIEPAC

Actors that contest infrastructures have strongly voiced the looming dispossession, environmental destruction and the taking away of livelihoods consequent on the many large-scale energy generation projects that feed into the SIEPAC grid (Colectivo Vocés Ecológicas, 2019; Bolaños, 2022). They embed these concerns in narratives on colonial global economy and war, in press releases of the transnational Mesoamerican Forum, which brought initiatives from Mexico and Central America together to discuss contestation strategies across the Central American corridor of intense infrastructure construction (Foro Mesoamericano, 2011). The Zapatista movement, arguably professionals in generating global publics during the 1990s and early 2000s, supported protests against SIEPAC infrastructures when these still remained unbuilt. Subcomandante Marcos, then its representative, expressed its concern that ‘the construction of the 1,830 km of power lines will mean deforestation, affecting ecosystems and the lives of communities. Our concern for SIEPAC focuses on possible hydroelectric projects on important rivers in the region that will be destroyed’ (Subcomandante Marcos, 2006). The movements contest the dominant discourse on energy futures (based on seemingly technical solutions such as infrastructures) at multiple sites, whether locally, through marches in capital cities, or through complaint mechanisms such as the one set up by the European Investment Bank. Transnational military operations such as the Merida Initiative, they claimed, were explicitly aimed at protecting the current wave of infrastructure investments and simultaneously resulted in escalations of violence and outright counterinsurgency practices against protest (Foro Mesoamericano, 2018).

Distinguishing between the actual site of material infrastructures as opposed to their planned sites complicates answers to the question of where precisely contestatory publics are located in relation to unbuilt infrastructures. For some contestatory publics to become visible, we have to follow the planning into the past, in other words, into the digital archives of such past mobilizations. In southern Costa Rica, the communities of Alfombra and Matapalo rejected plans by the National Electricity Agency (ICE), which was executing the Costa Rican stretch of SIEPAC construction. They feared the line would affect tourism, destroy primary forest, and destabilize stretches of land (TV Sur Canal 14, 2009). Eventually, ICE agreed to reroute the transmission line based partly on the communities’ suggestions (Interviews with senior consultant for ICE, May, 2022).

Contestation proved to possess political agency, for instance, when road blockages, marches and strategic litigation against wind energy platforms in Oaxaca, Mexico, led to one project's abandonment by French corporation EDF (SIPAZ, 2021). Similarly, in 2018 Costa Rican electricity agency IFE indefinitely suspended one of the major SIEPAC-feeding hydropower projects, El Diquís, already stalled for seven years due to long-term protest by indigenous communities, particularly the Térraba community (see Figure 5), even though some of the tunnels around the envisaged dam had already been built (Rojas, 2018). ICE had planned the Diquís dam as a cornerstone for electricity export to SIEPAC (ICE, 2017: 100–101). What the Diquís and earlier discarded projects close by have in common is the direct action of the communities that fear displacement and destruction of livelihoods. They claim additional large-scale dams are unnecessary to cover local energy demand (Rojas, 2018), making the project's projection towards needs elsewhere itself a reason for contestation.

The publics contesting dominant discourses of energy connectivity sit elsewhere as well. Since 2019 a cooperation between the Geocomunes collective, based in Mexico, which aims to make ‘visible the territorial logics of capital’, and the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation headquartered in Berlin, clearly an exercise in producing ‘counterexpertise’ (Bosworth, 2018), has led to the publication of a comprehensive, open access infrastructure and grid atlas on Central America, the Geovisualizador de la infraestructura eléctrica en Centroamérica (2021). This effort collects and makes accessible the very dispersed information on planned and operating local and transnational infrastructure projects and their investors. Despite this transnational effort, national and local-scale power relations defined the political agency that could unfold from that resistance. Contestation persists after building, but it has become more fragmented and place-based, targeting individual subprojects envisaged to feed energy into the grid.

Digital media sources allow organizational processes and efforts by protestors to ‘go global’ and appeal to transnational publics, as well as appeals to global investors to be traced. Public relations videos about the Mesoamerican Project address an international (Spanish-speaking) audience, mainly planners, investors and corporations that indirectly benefit from infrastructure investments. The Costa Rican Electricity Agency (ICE), one of the shareholders that built SIEPAC, provides an extensive Youtube archive on electricity, connection and sustainable energy sources, insisting the motive of solidarity oriented the construction of transnational electricity infrastructure (Grupo ICE, n.d.). Videos in the Mesoamerican Project executive committee's (2019) archive propose a specific project narrative. Discourses of ‘inclusive development’ complement economic connection, but never show the beneficiaries’ individual stories; their technical language and pictures of high-tech control rooms illustrate the project's imagined and aspirational publics. Of the protest against the SIEPAC transmission line which led to its rerouting in southern Costa Rica, only a few local newspaper articles and the archive of a Facebook group remain (Comité Alfombra, 2010). The possibility of juxtaposing these narratives allows researchers to shrink the distance, and grasp at least tentatively the contradictions between institutional representation and contestatory publics.

MEDRING

Despite their seemingly technocratic nature, the grid projects that are a direct component of the envisaged ring are widely perceived as infrastructural colonization and are met with various forms of local and transnational resistance (Hamouchene, 2016; Allan et al., 2021). The actors behind such forms of resistance are primarily concerned with the selective nature of the envisaged connectivity—enabling highly selective forms of bidirectional flow of electricity across the Mediterranean, while heavily containing any form of northward human migration and greenwashing Morocco's occupation of Western Sahara. They involve both local citizens and communities, as well as transnationally organized activists.

Citizens of Ouarzazate have protested against the construction of the country's largest solar megaplant, facilitated by the expropriation of communal lands via colonial strategies of dispossession (Rignall, 2016). Other forms of seemingly ‘local’ protest have shown themselves adept at identifying the ‘elsewheres’ of the MedRing project's envisaged energy infrastructures. Many Sahrawis are highly critical of the Moroccan regime's attempts at greenwashing its occupation of Western Sahara, and draw direct connections between Moroccan colonialism on the one hand, and local wind energy projects, pursued by Siemens, and electricity grids, constructed by Alstom, on the other (WSRW, 2014). Illegal electricity hook-ups in the poorest neighborhoods constitute, as argued by Allan et al. (2021: 10), an act of resistance that takes place elsewhere than standard accounts of Moroccan (energy) politics and Sahrawi resistance would assume. The politics of Sahrawi energy poverty and the Sahrawi struggle for independence are fought at multiple sites, including those of electricity production in Moroccan-occupied Western Sahara, of trans-Mediterranean electricity flows, of European electricity consumption, and of protest against high electricity prices in Morocco's urban centers.

While the continental European grid already connects—in its most southwestern stretch—with renewable energy plants and infrastructures in occupied territories, this will, once ongoing construction work on the EuroAsia interconnector is complete, also be the case in its most southeastern stretch. Once finalized, the EuroAsia interconnector will be the longest subsea interconnector worldwide (1,208 km), connecting Greece, Cyprus and Israel, and enabling better energy security and diversification for the latter. This not only harshly contrasts with regular power outages in neighboring Lebanon, and high electricity prices in the Palestinian territories, it also reshapes the space in which the politics of the Israeli (and Moroccan) occupation regime play out (see Schuetze, 2023).

Against this background, Hamza Hamouchene (2016: 8), an activist-researcher with the Amsterdam-based Transnational Institute (TNI), argues that the struggle for energy democracy in the Maghreb is confronted with a new type of ‘energy colonialism’. The setup of the TNI, an international research and advocacy institute, of Western Sahara Resource Watch (WSRW), a transnational solidarity network with the Sahrawi population, and of Who Profits (n.d.), an Israeli non-profit organization that maintains an online database of businesses benefiting from the occupation, follow and mirror the transnational nature of the envisaged Mediterranean electricity ring. Only by focusing on both the MedRing project's material sites of intervention and its elsewheres (see Massey 1994; 2007) can its transnational dimensions and connection to ‘energy colonialism’ be fully grasped.

In the case of the MedRing project it is also interesting to observe how visual depictions of the project, despite the latter's material state of incompletion, help reproduce controversial hierarchies of power. Portrayals of greater electricity integration as a means to ensure (European) energy security and development, as well as greater integration of renewables, are regularly complemented by discursive and graphic depictions of the project as overcoming established borders and opening the doors to a ‘common energy future’ (MedReg, 2022). This is presented as realizable via the empowerment of technocratic actors like Mediterranean electricity regulators. As stated in the magazine Middle East Electricity (2014: 87), ‘cable leads the way’. Far from mere empty words, such images have a strong productive dimension in so far as enduring North–South disparities in decision-making power and present forms of violent containment of South–North human mobility across the Mediterranean can now hide behind promises of future interconnectivity primarily aimed at aspirational publics situated in the global North.

While images such as the one discussed above push a narrative of commonality, at other times visual depictions of the project or of the ‘problem’ to be solved serve to pinpoint the site of intervention. The ‘EU Energy Strategy in the South Mediterranean’ (Duhamel and Beaussant, 2011: 26) for instance includes a visualization of a ring, which ‘is currently broken or interrupted in several places’ (ibid.: 21) and requires fixing. The colors used for annual energy exchanges (blue in the Mediterranean North and red in the Mediterranean South) help establish the location of the ‘deficiency’ at hand. These aesthetics evidence an understanding of North Africa as both literally and figuratively disconnected and seemingly requiring European-led efforts at connection. Attending to media visualizations thus provides indications not only of the ultimate aims of the project, but also about the controversies it may engender in its unbuilt state.

Looking at how contestatory publics emerge and where their tactics of resistance take place evinces how transnational energy infrastructure projects shape the energy futures that are imaginable and the contexts within which these can be contested, regardless of the projects’ own states of (in)completion. The geography of actions and coalitions brought together across these three megaprojects provide evidence of the transnational, contestatory publics that emerge at different times and in different political spaces. As illustrated above, one of the ways that transnational energy projects come into being is not through physical implementation, but through town hall meetings, online forums, and through other spaces in which these projects' contestatory and/or aspirational publics are formed and performed. These publics are localized both at the material sites of infrastructural intervention, and in the wider energy communities that these sites (are planned to) connect with via ‘energized practices’ based on fossil fuel extraction and/or forms of dispossession and displacement (Kramarz et al., 2021). Where planned pipelines, as well as overground and submarine electricity interconnectors remain wholly or partially unbuilt, their publics illustrate that energy infrastructure has important effects far beyond the immediate sites of their realization (and before their materialization).

Conclusion

The deployment of global infrastructure depends on (and in turn shapes) myriad political, institutional and financial arrangements (analyzed in the first section of this article), as well as sites where transnational publics make their claims known (discussed in the second section). The multisitedness of these projects, of the involved actors and of emerging publics—coupled with the immobilizing effects and rethinking of fieldwork in pandemic times—calls for renewed attention to research approaches that attend to transnational infrastructure projects’ important ‘elsewheres’.

Methodologically, this article has demonstrated how digital sites of data collection allow researchers to appreciate and juxtapose the disparate constructions of reality around infrastructure projects from both ends of the power spectrum. Following infrastructural power relations is one way of following that which is not yet built. In each case, power relations inherent to these infrastructure megaprojects play out or are reproduced through visuals, dialogues and texts that often only exist online. Controversies around energy infrastructures and contradictory promises exist in closer proximity in virtual space, allowing them to be seized on for further inquiry or theorization. Transnational spaces are not only implicated in the becoming of energy projects. Critiques and efforts to stop, revise or undo global infrastructure, likewise, take place in global spaces. Contestatory and/or aspirational publics emerge before, during and after the materialization of transnational energy infrastructure projects. Accordingly, they point us to the real and virtual elsewheres that must be added to the spatial practices of researchers studying unfinished and multisited infrastructure projects. Considering the multiplicity of agents involved in its creation and use, and its broader framing by counterpublics, material infrastructure is not the only element that reveals the conflicting social relations around a given energy-infrastructure megaproject, nor are the pylons or pipelines, which have an appreciable impact on the physical landscape, the only connective dots and lines. In fact, the energy infrastructures we research reach far beyond the countries that share their electricity and/or energy markets. Transnational infrastructure projects come into being through transnational and virtual sites that offer new alternatives to researchers under uncertain (post)pandemic life conditions.

While we were only able to actually travel to selected physical sites of EACOP, SIEPAC and MedRing towards the end of our research project, we had already encountered important ‘elsewheres’ before these physical arrivals. Researching digital archives is no substitute for ‘being there’ but does complement research at the material sites of (attempted) infrastructural realization. Digital technologies unveil qualitative data in their own right, and, in addition, provide methodological openings for researchers to transition to written correspondence or real-time interactions with interlocutors. The highly context-dependent geographies of the materiality, financing, contracting and contestation of transnational energy infrastructures are an inherent part of such projects that research must attend to. Yet all transnational (energy) infrastructure projects also have their real and virtual ‘elsewheres’. Such sites that may be partially unbuilt or seemingly unrelated to the project of concern will perhaps on a second glance prove to be transnationally connected, and/or at places where no infrastructures and associated construction sites are to be seen.

Biographies

Maren Larsen, Urban Studies, University of Basel, Hebelstrasse 3, 4056 Basel, Switzerland, [email protected]

Alke Jenss, Arnold Bergstraesser Institute, Windausstraße 16, 79110 Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany, [email protected]

Benjamin Schuetze, Arnold Bergstraesser Institute, Windausstraße 16, 79110 Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany, [email protected]

Kenny Cupers, Urban Studies, University of Basel, Hebelstrasse 3, 4056 Basel, Switzerland, [email protected]

References

- 1 The above-mentioned projects were selected for their transnational nature, their location in the global South, their variable states of being (unbuilt, semi-built and already built) and their use of both fossil fuels and renewable energy sources. The focus on energy projects as opposed to other types of large-scale infrastructure project is deliberate, as such projects ‘invoke modernity in a particular way, enabling lighting, movement, and communication’ (Jenss and Schuetze, 2023: 2) as well as fulfilling certain notions of development, organizing democratic demands (Mitchell, 2011), and/or enacting different forms of containment and exclusion.

- 2 There is a rich literature that discusses the transnationalization of the public and the latter's conceptual uncoupling from the nation state—a process and debate that predates the advent of the digital communication technologies described in this article (Oleson, 2005; Fraser, 2007). It is beyond the scope of this article to review this literature or to argue any novel contribution to it. Rather, in our discussion of digital and transnational publics assembled around (or against) emergent infrastructure, we seek to draw attention to the ways in which people, ideas and movements rooted in different places contribute to the (un)becoming of transnational infrastructures and rearticulations of their relations far beyond but variably connected to the sites of their construction (Massey, 2007).

- 3 The interconnection between the field sites where researchers arrive at their infrastructural objects and the analytical thrust of the arguments has been made explicit in the study of global infrastructure through introductory narratives of arrival. Examples include researchers’ arrival in shareholder offices to emphasize cash pipelines in oil infrastructure (Marriot and Minio Paluello, 2012), by helicopter to remain faithful to the abstracting views of capitalism (Appel, 2019), and on ships to hold together the place and space of Arab Gulf trade routes (Khalili, 2020). In the same vein, our initial pandemic-induced inability to travel shaped our foray into digital spaces and places beyond construction sites through which energy infrastructure's elsewheres are reticulated. Field visits to the sites of these real, upcoming and imagined energy infrastructures helped to galvanize their role and significance.

- 4 See Barry (2013: 49–55) for a discussion of Amnesty International's contestation of the BTC pipeline and broader interrogation of the project's document and information archive through local organizations supported by and connected to wider global networks. See Massey (2007: 201–9) for a discussion of transnational political organizing and London's global, economic role in the oil and gas industry.