CLIMATE-JUST HOUSING: A Socio-spatial Perspective on Climate Policy and Housing

We would like to thank the editor and three anonymous referees for their critical and constructive comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Abstract

Focusing on the nexus of climate and housing policy, this article analyzes the socio-spatial consequences of urban climate mitigation policies and the resultant need to broaden the concept of climate justice. By using the example of energy retrofitting in a low-income district in Kiel, Germany, the article examines cities’ dependence on real estate companies to reach low-carbon goals in a privatized housing market and the (potential) need to provide incentives for investment. As the case study shows, this can lead to a highly sensitive confluence of climate policy, private real estate investment and neighborhood development policy, which leads to a higher financial burden as well as the potential displacement and further political marginalization of current tenants. In light of these results, the article argues for the application of a climate justice frame in analyses of urban climate policies that integrates housing justice with spatial justice. Specifically, it calls for the right to climate-just housing; that is, for the right to affordable housing to be connected with the right to energy-efficient housing in one's own neighborhood. This implies the right to information and to urban space as political space, which in turn means the politicization of the targets, strategies and, not least, spaces of urban climate policy.

Introduction

In the context of the intensifying climate crisis and multilateral targets to reduce emissions, and influenced by growing civil society pressure, more and more cities have begun to adopt ambitious climate protection policies. In various cities this has culminated in declarations of a ‘climate emergency’, acknowledging the need for more drastic measures (see Haarstad et al., 2023). Although highly justified from an ecological point of view, this ethos bears the risk of implementing policies that lose sight of socio-spatial concerns.

In the academic literature, increased attention is being paid to the potential social impacts of intensified urban climate policies within a neoliberal urban development context, illustrated by concepts such as climate change experiments (Bulkeley et al., 2015), low-carbon gentrification (Bouzarovski et al., 2018), the climate-just city framework of Steele et al. (2012; 2018) and the growing conceptual field of climate urbanism (Broto et al., 2020). As the housing sector accounts for a large share of cities’ total emissions, many climate programs focus on retrofitting the housing stock. In line with Rice et al.'s claim that ‘there is no climate justice without a clear and central focus on housing justice’ (2020: 160), further work still needs to be done to analyze the materialization of climate policy in the context of housing and to consider how it affects and interacts with existing geographies of inequality and injustice. We argue that such analyses need to focus on the political and legal frame of spatial configurations, which include property relations as well as housing and neighborhood development policy. The scholarship on spatial justice offers multiple starting points for such a perspective (see e.g. Dikeç, 2001; Marcuse, 2009; Soja, 2010).

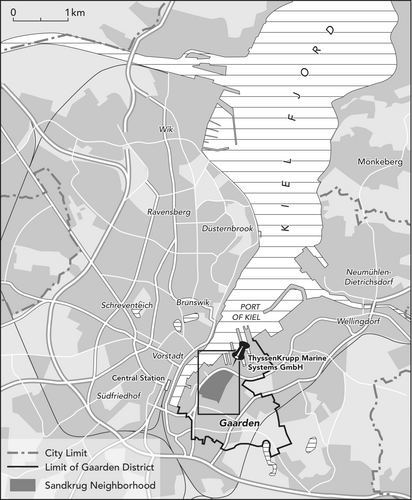

This article is developed around the empirical example of climate policy in Kiel, Germany and, more specifically, the energy-related redevelopment of the low-income district Kiel-Gaarden. This neighborhood redevelopment is part of Kiel's ‘Master Plan 100% Climate Protection’ (LH Kiel, 2017) to achieve climate neutrality by 2050, which gained momentum through the city's proclamation of a climate emergency in 2019. However, Kiel's municipality lacks access to the housing stock, which was completely privatized in 1999. Any progress in lowering household emissions therefore depends on real estate companies’ willingness to invest in energy retrofits. The city's neighborhood development policy thus relies on incentives and influence. This is illustrated by the case of Kiel-Gaarden, where neighborhood development measures in combination with a tightening housing market create a more investment-friendly context. The decision of a major real estate company to retrofit a significant part of its housing stock in the neighborhood marks a major step in Kiel's low-carbon policy—but also signifies possible shortages of affordable housing for low-income tenants in Kiel-Gaarden.

This article argues for an understanding of climate justice that integrates housing justice with spatial justice from both an academic and a political perspective. We analyze the socio-spatial effects of private-led retrofits through the interplay with structural conditions, housing policy and neighborhood development policy. From such a socio-spatially sensitive perspective, we discuss the concept of climate-just housing, understood as connecting the right to affordable housing with the right to energy-efficient and climate-resilient housing in one's own neighborhood. This latter point is crucial, because only by ensuring spatial justice can the displacement of less powerful population groups from city-center areas be prevented. There is a connection here to recent debates about the ‘renovation wave’ of the European Union's Green Deal and the concern of scholars and activists that this endeavor may become a ‘renoviction wave’ (this will be elaborated further in the next section).

The article's scope primarily engages with climate mitigation measures; hence, it does not embrace the discussion around climate adaptation policies. This is an analytical split. The two fields are of course strongly intertwined, as in the example of energy retrofitting, which both reduces carbon emissions as a result of less heating and protects tenants from high outside temperatures. However, apart from some indication of the implications of retrofitting for climate resilience, the article's scope does not allow consideration of the complex debate about adaptation justice (see Shi et al., 2016; Chu and Cannon, 2021). The conclusion offers some indications about how engagement with adaptation justice can be an important element of further research.

In the next section we connect the theoretical lines of climate justice, housing justice and spatial justice and pre-formulate our idea of the concept of climate-just housing. Following this, we provide an overview of tenancy law in Germany, before moving on to the substantive part of the article where we contextualize our case study and analyze the process of neighborhood redevelopment and the effects of rent increases within the field of neighborhood policy. Finally, we discuss our empirical findings and further elaborate the concept of climate-just housing.

The socio-spatial implications of urban climate policy

In the face of growing climate activism and the transfer of responsibility for meeting national emission reduction targets to the municipal level, many city governments have assigned increased importance to low-carbon policies. These policies have strong implications for urban inequalities and injustices. Connected to the uneven socio-spatial impact of climate change within cities (Anguelovski and Roberts, 2011; Miller Hesed and Ostergren, 2017), there is increasing scholarship about the justice implications of urban climate mitigation policies (Long and Rice, 2019; Broto et al., 2020; see also Robin and Broto, 2021 on climate urbanism). Critical scholars draw attention to the experimental character of low-carbon policies (Bulkeley et al., 2015) and to actor configurations and power constellations in urban governance regimes (Broto, 2017).

Within the debate on market-driven green transitions and green gentrification (Stevis and Felli, 2016; Anguelovski et al., 2019), the accelerated energy retrofitting of residential buildings is assuming increased significance. This has been analyzed in terms of energy justice (Bouzarovski and Simcock, 2017; Gillard et al., 2017; Grossmann, 2019), possible displacement dynamics because of rising rents (von Platten et al., 2022; see also Bouzarovski et al., 2018 on ‘low-carbon gentrification’), and the need to integrate social policy with climate policy (Seebauer et al., 2019). In the European political debate, this issue has gained greater relevance since the announcement of a ‘renovation wave’ as part of the European Union's Green Deal in 2020 (European Commission, 2020). Warning of a ‘renoviction wave’, FEANTSA (2022) analyzes the potential positive and negative social impacts of an aggressive housing renovation program in the various legal and political circumstances of EU member states. This ongoing debate involves consideration of issues around housing and spatial justice, but it has not yet conceptually integrated these two dimensions. Recognizing the strong overlap between climate justice and housing justice and the spatiality of this nexus, we argue for a conceptual framework that integrates an explicit spatialized and localized perspective on housing justice into the climate justice debate.

Following Steele et al. (2012; 2018), climate justice in cities needs to connect social, environmental and ecological justice with the specific local context; that is, the stories and practices of citizens, activists and policymakers. According to the environmental justice debate (Walker, 2012), we need to look at the distribution of both the benefits (e.g. new bike lanes) and the burdens (e.g. the cost distribution of energy retrofitting) of climate policy (i.e. distributive justice); who is involved in the planning and execution of low-carbon policies (i.e. procedural justice); and whose needs are being considered (i.e. justice of recognition). Transferring the climate justice idea to a local urban context therefore encompasses consideration of both marginalized communities that are more vulnerable to the impacts of a changing climate (such as heat waves, for instance), and the impacts of actually exercised climate mitigation and adaptation policies (such as rising rents and a changing neighborhood). This means we need to consider the potential outcomes when city governments that lack access to the housing stock attempt to create a more investment-friendly environment by giving incentives for private companies to invest in the energy efficiency of residential buildings. As energy retrofitting gains momentum through cities’ efforts towards climate neutrality, further work is needed to analyze the socio-spatial implications of this policy.

Housing justice is so far mostly negotiated in the context of activist groups and protests (Listerborn et al., 2020; Lima, 2021). It refers to housing as a fundamental need that every human being must be able to access. Unlike most commodities, housing is not a purely economic good that is freely available through the system of economic exploitation. A home is not readily interchangeable because of the diverse socio-cultural and socio-economic relationships that exist in the activity field of the home and the living environment more broadly. It is also not portable when people move because of its ‘immobility’. This psychological, social and cultural meaning of housing is central to the concept of housing justice and the demand for all population groups to have equal access to all urban spaces, not only to those that appear least attractive in the capitalist logic of use. This makes the right to housing a complex right in political practice (Wehrhahn, 2019). Overall, it is the fundamental spatial dimension of housing that calls for an analytical linkage with the concept of spatial justice.

The scholarship on spatial justice offers multiple connecting points to analyze the materialization of climate policy in the context of housing and how it affects and interacts with existing geographies of inequality (Bouzarovski and Simcock, 2017). By looking at the structural, historically embedded causes of spatial inequalities and the ‘dialectical relationship between (in)justice and spatiality’ (Dikeç, 2001: 1785), the concept of spatial justice takes into account the constructivist nature of space. This refers to the complex set of political and economic relations, practices and dynamics that (re)produce spatial constellations of power, stigmatization and inequality (Harvey, 1996; Soja, 2010). Following Dikeç (2001), regarding spatiality as a process and spatialization as a way to reproduce domination involves considering both ‘injustice in space’ and the (re)production of ‘injustice through space’ (ibid.: 1793–4; emphases in original). Injustice in space acknowledges that injustice materializes through specific distributional arrangements in space. Injustice through space relates to the structural dynamics that constantly (re)produce injustice. These include, for instance, property relations such as the privatized housing market, legislative rental regulations that come into effect in space, municipal power relations and the consequent policy priorities, and entrepreneurial activities.

Accordingly, such a spatial justice perspective looks at the reciprocal influence of spatial and social justice and offers a tool for identifying and analyzing the contents and foci of local policy measures and their implications for inequalities and (in)justice (see Marcuse, 2009). It highlights the political and legal frame of spatial configurations and helps us analyze how property constellations, housing policy and housing law interact with geographies of inequality and how this determines the socio-spatial outcome of climate policy. Furthermore, we need to consider Lefebvre's (1986) call for the right to the city as also including a right to information in order to enable political contestation. This sheds light on the need to politicize low-carbon policies and the urban spaces that they target. According to agonistic theory, such politicization enables negotiations about the rules of recognition that determine the distribution of social, economic and political capital and power—in other words, ‘recognition capital’ (Tully, 2000: 470). This underlines the work done by social conflicts in unmasking inequalities and injustices and disclosing different and diverging narratives and needs (see Mouffe, 2000; Weißermel, 2021).

Having discussed the interconnectedness of climate justice and housing on a local urban scale, as well as its spatiality, we now seek to pre-conceptualize the notion of climate-just housing to capture the manifold aspects and dimensions that come into play. First of all, we acknowledge the general right to dignified housing, as demanded by the housing justice movement. Housing needs to become both climate-friendly and climate-resilient in terms of lowering household emissions and protecting residents from heat waves through better insulation. This implies the need to prevent the displacement of low-income tenants through higher rents. Therefore, generally speaking, urban climate policy needs to acknowledge its interconnections and coupling effects with other policies, particularly within a neoliberalized housing market.

Climate-just housing, then, signifies the right to both affordable and climate-resilient housing in one's own neighborhood. It implies the fair distribution of climate policies, their benefits and costs. It encompasses justice of recognition concerning the particular needs and circumstances of marginalized communities, as well as the manifold effects of climate and neighborhood policy on them, including the potential reinforcement of inequalities in and through space. This requires an inherently spatial perspective on the urban social structures and socio-cultural particularities of neighborhoods targeted by low-carbon policies. In its interconnectedness with procedural justice, this dimension calls for the involvement of the affected residents, not merely through formalized participation measures but by enabling the neighborhood to become a political space of contestation concerning the shape of urban climate policy and its implementation.

Low-carbon redevelopment in Kiel-Gaarden, Germany

While the execution and effects of dominant types of retrofitting are highly controversial (Grossmann, 2019), it is undisputable that emissions from residential buildings must be reduced. Problems that may result from energy retrofitting have both structural causes (i.e. the legal and economic framework, which is discussed in the sub-section below on energy policy and tenancy law), and procedural ones (concerning the nature of the refurbishment process, also detailed more fully below), which are strongly interwoven. First of all, though, we provide some information about the methodological approach.

Methodology

The case study uses qualitative empirical data collected between 2019 and 2023. In total, 51 interviews1 were conducted with actors from the municipality, the real estate company and civil society as well as tenants affected by the redevelopment project. All interviews were guided and semi-structured. The public, economic and civil society actors were contacted in advance and the conversations were recorded and transcribed later on. Seven of these interviews were held with municipal actors from the department of climate policy, the building department and the district management, two with the regional manager of the real estate company, and one with a private district development initiative. In addition, seven interviews were conducted with local social workers and tenant activists.2 These interviews were analyzed with an open and experimental approach that enabled us to capture the local context comprising the socio-economic and tenant structures, main actors, municipal policies, economic activities and the surrounding discourses. This was accompanied by an analysis of municipal reports and data. The information gathered enabled the formulation of a questionnaire which served as an orientation template for both conducting and then coding and analyzing the tenant interviews.

Several visits to the Sandkrug neighborhood enabled 37 conversations with residents. Tenants were spontaneously approached by spending time in public spaces in front of the relevant residential buildings. This was supplemented by three stopovers at a neighborhood center. The neighborhood visits took place at different times in order to contact different socio-economic groups. The conversations were structured by the questionnaire and mostly conducted as individual interviews. Some interviews were undertaken with two or three tenants, which involved an interesting empirical addition as it stimulated critical exchanges between the interviewees regarding their experiences with the retrofitting process and rent increases. All of the tenant interviews were recorded with fieldnotes and later codified and analyzed on the basis of the questionnaire (see Kuckartz and Rädiker, 2022).

Energy policy and tenancy law

In European countries where the housing market is dominated by tenancy, such as Switzerland (57.7% tenants in 2018), Germany (53.5%) or Austria (48.6%), people are more vulnerable to rental market dynamics (Eurostat, 2023). Given that there is generally a high ownership rate in rural areas, the share of tenants is accordingly higher in urban areas and usually accounts for the majority of the urban population. In Berlin, for instance, the tenant rate in 2018 was 84% and in Hamburg 79.9% (DESTATIS, 2024).

In Germany, the sale of state-owned housing during the neoliberalization of urban development included a large share of low-rent apartments that were formerly social housing. Through these and subsequent large acquisitions, private real estate companies evolved into listed companies with considerable influence on the private rental housing market, albeit with regional variations. While their share nationwide is only 13% (in contrast to 43% owned by private individuals), in cities like Berlin, Hamburg and Munich as well as in our example of Kiel, private housing companies own around one-quarter of the rental housing stock (Savills, 2019). And since the erstwhile municipal housing stock consists mainly of (formerly) subsidized social housing, this seemingly modest share accounts for a large proportion of the lower rental price segment. This situation is embedded in a general trend towards an increasing market orientation and the financialization of housing (see Aalbers, 2016; Sarnow, 2019; Wehrhahn, 2019). In Germany, as in other countries with largely deregulated housing markets, continuously rising rents and an investment focus on high-price housing is leading to a constant reduction of the low and middle rental price segment.

In Kiel, the municipal housing stock consisted of buildings constructed in the 1950s to 1970s, mostly as subsidized housing in lower-income neighborhoods. Nowadays, these buildings urgently need refurbishment. By 1999, the city had sold its entire housing stock to a private company. After being resold several times, today it almost entirely belongs to Germany's biggest real estate company, which owns approximately one-quarter of the rental housing stock in Kiel (Kaufmann, 2013; Savills, 2019; Vonovia, n.d.). The city of Kiel has thus entirely lost direct access to and influence over the municipal rental market.

While this constellation has the potential to facilitate intensive retrofitting, provided the company is willing to engage in it, from a long-term perspective the costs are borne almost exclusively by the tenants. German tenancy law—more specifically, the modernization levy; see § 559 of the German Civil Code—allows for 8% of modernization3 costs to be added to the ‘cold rent’ (i.e. rent excluding heating costs; BMV, 2020). This includes energy-irrelevant measures such as the installation of balconies and elevators. Generally, tenants have no say and must accept these measures. Even after amortization—which takes 12 to 13 years if the modernization levy is applied in full—the rent is allowed to remain at the higher level, which makes modernization lucrative in the long run even without a change of tenant (and new lettings, of course, offer even greater opportunities to make a profit). However, this rent increase is not linked to actual energy savings after refurbishment, which is why ‘warm rent neutrality’ (i.e. where energy savings offset the increase in ‘cold rent’) is usually not achieved (BMV, 2017; Grossmann, 2019).

Tenant protection in Germany is thus counteracted by the modernization levy and the exclusion of such rent increases from rent control laws. Furthermore, retrofitting is not regarded as a valid reason for interim rent reductions. This situation must be seen in the context of a tight housing market, increasing rents in most German cities, and a decreasing share of social housing—which now represents only 4% of the entire residential stock (BBSR, 2016; die Unterzeichnenden, 2018). When those who receive transfer payments from the state (due to their low income) are affected by rent increases, there is a risk that the responsible authority will no longer cover the rent if a particular cost limit is exceeded.

Low-carbon redevelopment in Kiel-Gaarden

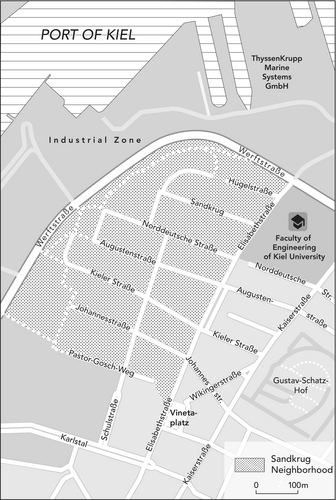

Kiel-Gaarden is one of seven so-called ‘Energy Districts’ in Kiel. With its policy program ‘Klimagaarden’ (from 2014) that aims to reduce household emissions, the area is a target for the municipal low-carbon policy. Recently, building refurbishment has achieved new momentum, as a major real estate company has decided to undertake energy-related redevelopment of the Sandkrug neighborhood within Gaarden (Figure 2). An analysis of the socio-spatial impacts of the neighborhood redevelopment must go beyond a simple focus on rent increases, which have not yet come fully into effect. Rather, we need to take a holistic view of the project's integration into the municipal climate and housing policy, neighborhood development policy and housing market dynamics. Therefore, we shall now provide a brief historical contextualization of the Gaarden district and Sandkrug neighborhood within Kiel before outlining the low-carbon redevelopment project, its integration into the current political and economic dynamics and implementation of the retrofit works to date. Finally, we will take a look at the already noticeable effects of the first rent increase.

contextualizing retrofitting in kiel-gaarden

Kiel-Gaarden represents an interesting example because, on the one hand, it is favorably located close to the city center, Kiel fjord and the university facilities (Figure 1), while on the other hand, it has historically been decoupled from the city center with a spatial concentration of underprivileged social groups. Gaarden is an old working-class neighborhood. Located directly next to Germany's biggest shipyards (Figure 2), it was shaped first by the growth of the shipyard industry and recruitment of foreign workers in the 1950s and then by the shipyard crisis, deindustrialization and massive job cuts from the 1980s onward. Consequently, the process of socio-spatial marginalization and concomitant growing stigmatization of the district (LH Kiel, 2014; 2020), which began in the 1980s, is rooted in the structural conditions of capitalism; namely, the dynamics of capital accumulation with its cycles of investment and disinvestment. Furthermore, the deregulated and restricted housing market in Kiel has led to a concentration of marginalized groups (e.g. those on low incomes, recipients of transfer payments and people with a migration background) in Gaarden because of lower rents, willing landlords and the inability of such groups to access the housing market in other neighborhoods. However, because of its location, the still relatively low rents, its multicultural character and the historical building substance at its center, Gaarden offers a potentially favorable frame for neighborhood upgrading.

Neighborhood policies targeting this socio-spatial marginalization have failed to deal with its structural roots. In 2000, Gaarden became part of the federal ‘social city’ program for so-called disadvantaged neighborhoods. In light of an active civil society in Gaarden, which includes non-profit associations, migrants’ associations, sports clubs and political initiatives, the program tried to ensure construction measures were introduced with the involvement of the local population and it established a local office for neighborhood management and mediation with the city government. However, the budget for this was relatively small, successes remained sporadic, and both the inequalities and the negative image persisted. In 2018, the municipality started a neighborhood development program called ‘Gaarden10’ (read: ‘Gaarden to the power of 10’; LH Kiel, 2018), which draws together existing programs and initiatives. This new program openly aims to promote social mixing and upgrading by bundling public and private capital for urban development projects, including promotion of the creative economy and public order. The program expects higher-income tenants to move into the district, but also students, particularly as it includes an extension of the university's faculty of engineering (Figure 2).

Given that the Gaarden district is expected to become more attractive and the housing market is currently experiencing the highest percentage increase of its rental prices citywide (IB.SH, 2020), the context is more investor-friendly than in the past. This is in line with the continuously increasing land values in Gaarden, with the Sandkrug neighborhood doubling its land value over the last eight years (GDI-SH, 2023). One integral part of the district development policy is neighborhood redevelopment, with a focus on energy retrofitting. However, the municipality has no access to the existing housing stock and is dependent on the investment patterns of private owners. After years without significant progress for ‘Klimagaarden’, in 2018 the biggest German real estate company, a listed enterprise, decided to retrofit its (formerly municipal) housing stock in the Sandkrug neighborhood (Figure 2). After additional property purchases, the company now owns almost the entire residential area, which allows holistic redevelopment.

The Sandkrug neighborhood has a relatively favorable location within Gaarden and the city of Kiel. It enjoys fairly quiet, somewhat elevated surroundings with a view of Kiel fjord and the shipyards. In the immediate vicinity is the university's faculty of engineering and the center of Gaarden with retail, gastronomy and multicultural appeal. Despite its central functions, Gaarden's connection to the western central city with the principal commercial center and the main university campus is blocked by the shipyards, major roads and parking lots. However, this will change significantly when a new light rail connection for the engineering faculty is built. Building on the influx of students and higher-income tenants, the company plans to upgrade the outdoor area of the future ‘Förde Quarter’, integrating, for instance, a mobility concept tailored to young tenants with shared cargo bikes and e-scooters (real estate regional manager, March 2020). Regarding the residential buildings, the project includes energy retrofitting (facade insulation, window replacement, roof renovation, installation of solar panels), balcony additions and building extensions (Figure 3). The company's redevelopment project is a significant component for achieving the municipality's emission reduction goals and is hence integrated into both the low-carbon program ‘Klimagaarden’ and the district development project ‘Gaarden10’. Given the declaration of a climate emergency, this offers the opportunity to reduce household emissions while also integrating the district socio-economically through investment and social mixing.

The real estate company has been heavily criticized regarding its corporate investment policy (Unger, 2018; Schipper, 2022). With a shareholder policy of maximum and reliable gain, the critique highlights an absence of investment, large bills for ancillary costs, and rent increases due to modernization or new lettings (Schipper, 2022). Residential buildings in Sandkrug previously attracted press attention due to their precarious structural conditions and the absence of investment (Schwenke, 2019). Now, however, the regional manager (March 2020) explained that the neighborhood's potential and the current favorable market conditions have led the company to pursue large-scale refurbishment. Prior to the retrofitting works, the Sandkrug neighborhood included a large share of older people and people with a migration background, many of them receiving state-funded transfer payments (real estate regional manager, March 2020; district manager, May 2021; tenants, July 2021 and February 2023).

implementation and impact of the low-carbon redevelopment

The retrofitting works in the Sandkrug neighborhood began in 2018 and the first building was finished in autumn 2019. Others followed in a delayed process, taking up to three years. Conversations with current tenants revealed deficiencies in the communication policy of both the municipality and the real estate company regarding the project design and the importance of the Sandkrug neighborhood for the city's climate neutrality program, for ‘Klimagaarden’ and the district development project ‘Gaarden10’. Indeed, the majority of tenants had never heard of Klimagaarden, a program predominantly directed towards property owners.

It was therefore apparent that the significance of the energy-related redevelopment of the Sandkrug neighborhood—not only as an indication of the Klimagaarden program's impact and success but also for achieving the municipality's low-carbon targets—had not been communicated to the Sandkrug tenants. This was stated by several tenants in individual interviews (January 2021; December 2021; July 2023) and in group conversations (February 2023). Many tenants acknowledged the energy effect (particularly with regards to their own expenses), as was confirmed in interviews after the residential retrofit was completed (June 2022; February 2023; March 2023), and several tenants appreciated the upgrade of the apartments and the neighborhood as a whole (September 2021; March 2023). At the same time, however, a number of them—particularly long-term residents—worried about the upward rental price trend in Gaarden, and in Kiel more generally (June 2022; February 2023; March 2023). In a group interview, tenants framed the retrofits as a ‘profit strategy’ (17 June 2022) of the real estate company.

The poor communication and lack of involvement by the city in the project's execution is reflected particularly in perceptions of the project's implementation. The construction works, which in some cases lasted two to three years with repeated interruptions, were experienced by residents as very stressful or ‘terrible’ (14 February 2023), especially because of noise exposure and unfinished apartments (June 2022; January 2023; March 2023). One tenant described this period as unbearable: her balcony was dismounted for three years and water leaked through the new windows because of missing seals (September 2021). Another tenant spoke of water damage occurring in his apartment when there was only a temporary roof of tarps for several days during the winter (March 2020). The real estate company's neighborhood office was shut at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic and, at the time of writing this article, is still officially ‘closed because of Corona’. Thus, tenants had to contact the principal office in Bochum, Germany; a process they described as very complicated and often inconclusive. Tenants therefore felt abandoned in the midst of a delayed and burdensome refurbishment process. They were never included in the project's design or implementation and nor were they informed about the role it played in the municipality's overall climate policy.

effects of the first rent increase

In relation to rent increases connected with the modernization levy, during interviews in January and March 2020 the company's regional manager emphasized the efforts made to avoid tenant displacement. The rent increases of two euros per square meter (the legally permitted limit on the basic rent) were thus staggered, beginning with an increase of one euro in the first year after the construction work was completed and the remainder split over the next four years. Moreover, the company argued that it had refrained from adjusting existing rents in line with the rent index since 2017, which relativized the pending increases (Geist, 2022). However, this argument was challenged by the press and tenants, who argued that the company had failed to maintain the apartments for years, to the point that they were completely run down (see above).

In residential buildings where the refurbishments had been completed (see Figures 4 and 5), rents had already increased by 25–44% (authors’ calculation based on 10 surveyed rent increases). In July 2021, barely two years after the first residential building was completed, the remaining tenants stated that more than half the tenants had left, and this was later confirmed in a group interview on 14 February 2023: ‘Many old people lived here. Some have died, some had to move away’. According to the tenants of several buildings, interviewed both before and after the retrofitting was completed (September 2021; June 2022; March 2023), several older people had moved out, particularly those receiving transfer payments. This was highlighted by one tenant who had lived in her building for 20 years: ‘The Bürgergeld4 recipients are all gone’ (7 March 2023a). Another tenant who had lived in the neighborhood for 12 years knew several pensioners who worried that ‘if rents continue to rise, we cannot afford them anymore’ (7 March 2023f). Although the current tenants now needed less heating, no savings had materialized yet due to rising energy costs since 2022 and high back payments from the previous year, as expressed by residents in February 2023. This led to a considerable additional financial burden, creating the impression that: ‘Living here has become very expensive’ (14 February 2023a). Particularly striking was the fact that most of the tenants interviewed were unaware of the staggered rent increases continuing for the next four years.

As mainly older people and transfer payment recipients had moved out and those who had moved in were predominantly students and people from Kiel's surrounding area and nearby cities (as reported by tenants of those first three finished buildings in February and March 2023), so a gradual change in the composition of the neighborhood's population was already apparent. Given the pending rent increases and the high level of new lettings, this trend is expected to intensify. This was confirmed both by better-off tenants supporting this change with statements such as: ‘It has become quieter … there are more students, it has changed for the better’ (7 March 2023a); and by tenants critical of the process, who had the impression that the real estate company ‘strives to change the clientele’ (7 March 2023f).

According to two incoming tenants, their agent called the Sandkrug neighborhood a ‘showcase property’ and stated that ‘after redevelopment, the upgrading will be complete’ (7 March 2023b). This should be viewed in the context of the intensified neighborhood development policy, which includes infrastructural upgrading with the significant extension of the university's faculty of engineering and the planned light rail connection, as well as a tightening housing market with rents rising disproportionately and increasing land values (see the earlier section contextualizing the retrofitting in Kiel-Gaarden). An examination of current advertisements for apartments to rent showed that rents for new lettings had already reached the level of the citywide average, which had also risen sharply in recent years. This confirms the assessment of one tenant that affordable housing in the city is disappearing: ‘Gaarden is already the end of the line … If they push us out of here, where are we supposed to go?’ (7 March 2023f). Similarly, an older tenant who had lived in the neighborhood for 32 years asked: ‘Should only the rich people live here?’ (17 June 2022).

According to the tenants we interviewed, the neighborhood is not well connected or well organized in social terms. Tenants did not network or engage in any protest action, despite their worries and complaints regarding the rising rents and general concerns about gentrification in Gaarden, which has become a strong discourse here in recent years and was confirmed by the district manager (May 2021), the tenant advisory service Mieterbündnis Kiel (December 2019), the social counseling and tenants’ rights initiative Mietwucher Gaarden (December 2019; February 2023), and by several Sandkrug residents during the empirical investigations (see above). There is, however, one case of ongoing resistance. Before the initiation of the refurbishment of their residential building, a group of tenants lodged a complaint about inconsistencies and inaccurate construction data in the modernization announcement. Led by a tenant with contacts to Mietwucher Gaarden, the group organized and—guided by the social counseling people—took concerted action against the company and its procedures. They refused to cooperate with the company and filed a pending lawsuit about the false announcement in order to reject the rent increases (September 2020; June 2023).

Over time, many families withdrew from the lawsuit for fear of having their rental contracts terminated. After the retrofitting was completed, those tenants who had resisted—as told by the group's leader (June 2023) and contrary to the company's announcement—received a full rent increase of two euros. At the time of writing this article, the group has not yet received the refurbishment bill as requested and is preparing a second lawsuit, so the outcome is still unclear. The initiator of this tenant resistance group argued that the refurbishment is a profit strategy rather than being energy related, since all the company's buildings were being refurbished, even if this was irrelevant in terms of energy efficiency. Observing the cooperation between the company and the municipality and other redevelopment projects in the district including residential construction, he assumed the goal was actually to change the district's reputation and ‘get away from the “ghetto-image”’ (29 September 2020).

The spatiality of urban climate justice and the concept of climate-just housing

The need for a spatial justice perspective on low-carbon policies

Steele et al. (2012; 2018) argue that there is a need to integrate the social and ecological dimensions of planning in order to achieve a climate-just city, which implies consideration of ‘the situated practices of social/environmental exclusion and attachment’ (Steele et al., 2012: 75). Pointing to the ‘spatiality and materiality of urban injustice’, they focus on the increased vulnerability to climate change of the urban poor because of infrastructural disinvestment (see the earlier section on the socio-spatial implications of urban climate policy). We, in turn, argue for the need to broaden analysis by bringing an increased focus to bear on low-carbon investment and its implications in low-income neighborhoods. Investment in precarious housing stock and infrastructure is mandatory from both an ecological and a social viewpoint. In light of increasing heat waves due to climate change and the urban heat island effect, better insulated residential buildings are an important component of climate change adaptation. However, attention must be paid to the risk of further impoverishment and possible displacement as a result of rent increases. Given the accelerated urban climate policy and related efforts in energy retrofitting, we need to look at climate policy in concrete terms, including the legal regulation of cost distribution and how this confluence materializes in space. Analytical findings from case studies like ours will have to be conceptually discussed using a spatial justice approach in order to foster the further conceptualization of climate-just housing.

The spatial concentration of poverty and underprivileged groups is a characteristic of cities in capitalism (see Soja, 2010). However, this is not simply the result of undisrupted capital movements, but for the most part is due to the concrete decisions of landlords concerning their letting strategies (e.g. profit by no investment vs. investment and higher rents; non/acceptance of minorities) and of political actors concerning housing and neighborhood policies (e.g. neighborhood development programs, selecting who should receive transfer payments, public housing provision). These decisions take place within the scope of legal possibilities. Thus, both structural forces and their congruence with actors’ decisions and practices need to be considered.

These decisions and practices occur within the context of the conditions and future expectations of the housing market and wider investment dynamics. Inequalities can hence be interpreted as injustices if people, for instance, do not segregate voluntarily but are forced to move to a specific neighborhood because of housing market restrictions, or have to leave their locality for a more peripheral and cheaper place. Space builds the material setting for the constant reproduction of these dynamic relations between the structural context, economic and political decisions (see Bouzarovksi and Simcock, 2017). Spatial injustices thus localize, structure and reproduce social injustices that are based on economically produced inequality and politically programmed (or at least politically tolerated) displacements and discrimination, as in the case of housing markets.

Privatized housing and the eco-social paradox

The case of Kiel-Gaarden shows the dilemma of having a privatized municipal housing stock, the consequent dependence on private real estate companies for achieving low-carbon goals, and the resulting need to give incentives for refurbishment, for instance through the frame of an upgrading policy. This constellation is highly sensitive as it involves urgent climate change mitigation and adaptation measures as well as the housing question. In Germany, both these fields have recently attracted enormous public attention because of the accelerating climate crisis and an increasingly exclusive housing market. Climate activism and tenant activism have thus emerged as the two biggest fields of social mobilization. As we have seen, the ecological and social problems these activists call attention to are profoundly interconnected and share similar structural roots. However, despite the political potential that activist cooperation would have, climate and tenant activist groups largely act independently of each other. The structural conditions of the market logic and legislation under which the housing sector has been operating since it was deregulated in the 1990s and 2000s are important here (see the earlier discussion on energy policy and tenancy law) as they play social and environmental demands off against each other. The assertion of an ‘eco-social paradox’ (Holm, 2011) or a ‘new socio-ecological contradiction’ (Rice et al., 2020: 145) suggests that ecological and social goals are mutually incompatible.

This results in a situation where climate activist groups in Kiel like Fridays for Future or the citizen initiative Klimanotstand (Climate Emergency) call for immediate and accelerated energy retrofitting of the entire housing stock without taking account of tenant concerns (citizen initiative activist April 2021; Fridays for Future Kiel, 2023), while tenant activists in Gaarden strongly oppose energy-based retrofits and do not engage with attempts to reconcile tenant protection and climate mitigation measures, as highlighted by an activist from the tenants’ rights initiative (December 2019). Similarly, projects for the ecological transformation of transport, which is a core aspect of climate activism, are planned on the edge of Gaarden (e.g. bike lanes and restricting roads for automobiles), but are interpreted by tenant activists as forerunners of gentrification (Mieterbündnis Kiel, December 2019; Mietwucher Gaarden, December 2019; leader of the Sandkrug tenant resistance group, September 2020).

Associated with this, an employee of the climate protection department (November 2019) raised the problem of climate policy in Kiel being predominantly negotiated between municipal and private stakeholders and the educated middle class. Yet in Gaarden, ‘climate protection is not a topic at all, for social reasons, many have those everyday problems’, as the district manager underlines (10 May 2021). This lack of integration is also reflected in the Sandkrug neighborhood, where the lack of information and depoliticized character of the redevelopment project make it difficult for tenants to politically organize and connect to local tenant activism in Gaarden, let alone to climate justice issues. This is problematic with regards both to the cohesion of an already highly unequal society and to generating social support for climate policy. When a low-carbon policy materializes through investment and use of the modernization levy in low-income neighborhoods, the resultant increases in rents may either lead to (increased) financial precarity or the displacement of tenants to spatially more marginal residential areas and buildings which are probably badly insulated. Either way, the existing conflict around distribution is intensified and society becomes even more materially and discursively divided.

The spatial injustices of low-carbon neighborhood redevelopment

The example of Kiel-Gaarden shows that spatialized neighborhood development policies may reduce the spatial marginalization of a neighborhood, in that it becomes better integrated into capital investment cycles and where an influx of students and higher-income groups leads to more interaction between the neighborhood and the wider city. However, as Marcuse (2009: 5) argues, ‘putting resources into the unjust space’ without ‘dealing with the relationships that have caused the injustice’ does not reduce the social marginalization of underprivileged inhabitants, because the marginalization is structurally rooted. Returning to Dikeç (2001), this rather static perspective on injustice in space fails to consider the structural and power dynamics that constantly reproduce injustice through space. These dynamics include housing market arrangements and dialogues with housing policy and tenancy law, the power structures and dynamics of the labor market, municipal dependence on private investment, and unequal access to education or urban participation schemes. The spatiality of injustice (injustice in space) is thus fundamentally interwoven with and conditioned by the injustice of spatiality (injustice through space). Therefore, compensating for spatial injustices with infrastructural improvements can lead to increased social injustice.

The requirements of housing-related, commercially implemented urban climate policy and the modernization levy both fuel the already rising rents. While the business policy of staggered rent increases may allow some tenants to remain in their apartments and benefit from well-insulated housing (at least in the short term), this does not correspond to low-income people moving into the neighborhood, since they are unable to afford the prices of new lettings. We can therefore assume that in the given structural context, low-income tenants are only able to afford energy-efficient and climate-resilient housing temporarily, if at all, until the final round of rent increases or the termination of a rental contract forces them to move.

To return to Marcuse (2009), spatial remedies without a focus on social inequalities potentially lead to displacement as a consequence. In the case of Kiel-Gaarden, the neighborhood's spatial integration may be realized through the spatial displacement of marginality, as the advancing neighborhood redevelopment provokes a successive exchange of tenants. This only relocates spatial injustices, however; it does not alleviate but rather intensifies social injustices in a different place with poorer connectivity and fewer infrastructural facilities or insulated apartments, thus actually intensifying the spatial marginalization of those affected. Climate policy and its confluence with neighborhood development policy therefore offers a frame for reproducing the existing mode of production, as the municipality's cooperation with the real estate company in the form of encouraging investments enables capital accumulation in the neighborhood, thus reinforcing exclusionary modes of domination through the capitalist housing market.

Apart from the further marginalization and displacement of current tenants, we also need to consider procedural and recognition-based injustices in the planning and implementation of low-carbon neighborhood redevelopment projects (Weißermel, 2023). In our case study, the project was planned by the company in line with economic expectations and aimed at a future clientele, without the current tenants being given prior information, let alone a chance to participate. Tenants faced significant barriers to information, as local communication channels with the company were largely blocked and the municipality did not appear in the project. Residents had no information about the refurbishment process or the reasons behind delays, and there was a complete lack of communication about the important role played by the project in Kiel's overall climate policy.

As Lefebvre (1986) noted, spatial justice—in its conception of the right to the city—also means the right ‘to a political space’. This means an ‘enabling right’ (Dikeç, 2001: 1790) to enter political struggle and through this struggle to take part in the negotiation of urban life and the contestation of urban development. This right requires full information and open communication channels. Climate justice thus needs to include spatial justice within its frame, in the sense of urban space as political space that enables agonistic encounters (Mouffe, 2000). It means contentious negotiations about the city's path to climate neutrality and the sectors, people, techniques and procedures involved. Climate-policy-related neighborhood redevelopment is based on technical measures and is thus often presented as a neutral and efficient low-carbon policy. However, similar to the enormous recent politicization of general questions of socio-ecological transformation, particularly regarding issues of mobility and energy generation (Sander and Weißermel, 2023), such redevelopment must also be repoliticized and connected to current socio-ecological conflicts and struggles. This includes the politicization of the neighborhood itself as a place of political contestation. It also means enabling the political struggle of the affected residents by uncovering socio-spatial inequalities and injustices as well as the residents’ perspectives, narratives and needs (see Steele et al., 2012; 2018).

Climate-just housing

The question of how we want to live in a changed climate and how we decarbonize our housing is a highly relevant social and existential issue, closely connected to the housing question and the character of climate policy in general. It is a thoroughly spatial issue that intersects with structures of injustice in and through space within a highly uneven capitalist housing market, with very specific spatial peculiarities and manifestations. Contesting the eco-social paradox, the need for low-emission housing with regards to energy efficiency, climate-responsive architecture and low-emission construction material is strongly interwoven with the concept of climate-just housing. Climate-just housing includes (1) the right to energy-efficient housing, which is increasingly important in light of rising energy prices. This is interwoven with (2) the right to climate-adapted housing in order to make housing resilient to climate change, e.g. the increasing heat exposure in cities. Finally, it signifies (3) the right to stay in one's neighborhood, which meets the demand of housing justice for housing access to all urban areas for all urban citizens in order to avoid spatial exclusion. Given that energy generation is closely connected to questions of residential energy consumption and costs, this concept can be usefully linked to debates around the decentralization and democratization of energy production (e.g. tenant electricity and energy cooperatives; see Becker and Naumann 2017). We thus take up Soja's (2009: 352) call to apply spatially conscious practices and politics to the context of climate policy and underline the need to consider structural conditions when addressing present and future social inequalities and injustices in space.

The importance and interconnectedness of the decarbonization of housing requires its politicization. We must enable political negotiations and agonistic encounters around this question that embrace all affected groups of (urban) society, political decision-makers and relevant economic actors such as real estate companies. Such politicization concerns, first, the actual housing-related low-carbon policy and the specific places of energy-related retrofitting as well as the design and implementation of such projects. Second, it concerns more structural questions of legal regulation, cost distribution and configurations of ownership. This includes problematizing the modernization levy, demanding its abolition or substantial reduction, and ensuring it is linked to actual energy savings in order to secure the proportionality and efficiency of investments and exclude energy-irrelevant modernization measures such as the mounting of balconies.

Arguments around financial feasibility must be countered by serious discussions about cost distribution and the (re)distribution of state resources for financing climate policy measures, since the current approach in Germany favors companies and middle- to high-income groups (see Löschel et al., 2021). One proposal that was introduced by environmental and tenant organizations and is currently under discussion is the one-third model, in which the state, landlords and tenants share the refurbishment costs. This includes a reduction of the modernization levy to 1.5% but allows landlords to accept state subsidies without having to deduct them from the costs they can claim (which effectively leads to an allocation of 3%; Mellwig and Pehnt, 2019).

At the municipal level, the key to greater access to relevant infrastructure and, consequently, increased municipal agency lies in the ownership of urban land (Wehrhahn, 2019). In order to allow climate-just housing, climate policy and housing must be disconnected from the market logic and democratized. In contrast to past neoliberal policies, cities need to create or enlarge their communal housing stock through new construction and the re-municipalization of private housing so as to create a market-relevant counterweight to private players and, in turn, influence average rents. Central to this is a legal right of first refusal, which enables municipalities to enter into a valid purchase contract for a residential building in place of the commercial buyer. Because of a controversial federal court decision, this right is currently suspended in Germany, but it is strongly supported by political factions of the left and center as well as tenant advocates.

In this respect, a high degree of politicization of the housing issue can be seen in the Berlin civil society initiative ‘Expropriating Deutsche Wohnen and Co.’ (‘Deutsche Wohnen und Co. enteignen’; see Vollmer and Gutiérrez, 2022). In 2021, there was a successful referendum demanding the re-municipalization of all the housing stock of real estate companies that own more than 3,000 apartments in Berlin; the municipal government now has to work out a constitutional legislative proposal to implement this referendum decision. Integrating the climate issue into the politicized housing debate would allow engagement with the alleged eco-social paradox and demonstrate the interconnectedness of climate and housing justice issues and their common structural roots of injustice. We argue that the concept of climate-just housing offers a useful frame for the politicization of the climate-housing nexus.

Conclusion

Using the example of a low-carbon neighborhood redevelopment in Kiel-Gaarden, this article addressed the need for increased research on case studies involving low-carbon investments in low-income neighborhoods within the privatized rental market (see von Platten et al., 2022 as one of the few studies on this). When investment is largely undertaken by big real estate companies, city governments have to incentivize them to implement refurbishment work in order to meet the low-carbon targets. As in our case study, this can be achieved through neighborhood upgrading projects that make investments more attractive. Together with the resulting rent increases from private-led retrofitting, this can trigger a twofold displacement pressure. While energy retrofitting is indispensable from an ecological point of view and has the potential to reduce energy costs and make tenants less vulnerable to heat waves, in Germany the current political and legal situation renders energy retrofitting an instrument for increasing rents and enhancing profit. Clearly, if technical low-carbon measures are implemented without considering socio-spatial inequalities, this can aggravate conflicts of distribution and socio-spatial inequalities, which, again, has negative consequences for societal cohesion and support for climate policy.

Our findings confirm the need for a thoroughly spatial perspective on housing within climate mitigation policies. In light of the present day's intensified focus on urban climate policy and hence energy retrofitting, we argue that, first, it is imperative to apply a climate justice frame to the analysis of such climate mitigation policies; second, this perspective needs to integrate spatial justice with housing justice. The integration of a spatial justice perspective in our discussion has demonstrated the potential of such an approach for critically examining the possible consequences of urban climate policy. This involves the spatial manifestation of inequality and injustice through the spatial concentration of marginalized groups or processes of spatial displacement. Furthermore, it concerns the structures and dynamics that reproduce inequality and injustice through space. These include, for instance, local housing market arrangements and their reproduction through housing policy and tenancy law, municipalities’ dependence on private investment, as well as unequal access to education, information or urban participation schemes. Consequently, local low-carbon investments may further exacerbate spatial injustices.

While the debate about a market-driven green transition increasingly involves consideration of housing justice and spatial justice issues (Bouzarovski and Simcock, 2017; Rice et al., 2020), we identified a consistent failure to conceptually integrate these dimensions. Hence, we developed the concept of climate-just housing as a conceptual proposal and a starting point for integrating housing justice and spatial justice into the urban climate justice debate. This concept is based on the premise that in the current socio-ecological crisis, neither ecological nor social rights can be compromised. Climate-just housing subsumes the right to energy-efficient housing, the right to climate-resilient housing and the right to stay in one's neighborhood. According to Lefebvre's (1986) right to information and to urban space as political space, this involves the right to enter the political struggle around the identification, elaboration and implementation of low-carbon measures. It requires the politicization of urban climate policy and its concrete spaces such as refurbished neighborhoods. Those affected must be actively informed, with full transparency and open communication channels for both public and private actors.

There are strong structural and politico-economic barriers to the realization of these principles and they must be tackled. First, legislative reforms are required, as is a public housing policy that recognizes the public security of urban land as essential to spatial and housing justice in the city. This would represent a fundamental political transformation of the neoliberal and financialization-driven paradigm. Second, the politicization of the climate-housing nexus and the enabling of agonistic encounters around urban climate policy are necessary. A joining of the forces and demands of climate activism and tenant activism would have the political potential to expose the interplay between ecological and social issues, the interconnected inequalities and injustices and their similar structural roots. Given the seriousness of this topic for our future social coexistence and in order to stimulate discussion about viable alternatives, there need to be more studies of cases within similar or different structural and legal contexts. In addition, it would be interesting to explore the extent to which experiences and findings from more radical examples, such as refurbishment programs in tenement syndicates (Hurlin, 2018) or so-called eco-villages (Pickerill et al., 2023), could be made fruitful for privatized contexts.

While our discussion already highlights some considerable overlap between mitigation measures—such as residential retrofitting in relation to climate adaptation concerns—greater involvement in the discussion on adaptation justice could help to further develop the concept of climate-just housing. Among other factors, this concerns the hotly debated integration of justice into all steps of urban development and planning (Fünfgeld and Schmid, 2020; Chu and Cannon, 2021). Furthermore, the frequent reference in this discussion to so-called vulnerable and marginalized groups and their involvement in the planning process (Shi et al., 2016) could help to anchor and operationalize a right to good insulation and suggest additional components of climate-resilient housing. Finally, given the risk that, in a privatized context, typical adaptation measures such as the greening of residential districts could further fuel rises in rents (Anguelovski et al., 2019), discussions about climate-just housing should integrate both climate mitigation and adaptation policies.

Cities need to embrace a spatially sensitive understanding of the climate-housing nexus in order to avoid increasing socio-spatial inequalities. Adopting the principles of climate-just housing would be a starting point to turn low-carbon transformation into a societal project that seizes the opportunity of using its transformative potential to create a less unequal and more democratic society.

Biographies

Sören Weißermel, Department of Geography, Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel/Kiel University, Ludewig-Meyn-Str. 8, 24118 Kiel, Germany, [email protected]

Rainer Wehrhahn, Department of Geography, Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel, Ludewig-Meyn-Str. 8, 24118 Kiel, Germany, [email protected]

References

- 1 The discussion clearly indicates which actors provided which information, as well as the month and year of the interview for chronological classification. The exact date is given where direct quotations are used.

- 2 Specifically, the tenant advisory service Mieterbündnis Kiel, the social counseling and tenants’ rights initiative Mietwucher Gaarden, and the leader of the tenant resistance group in the Sandkrug neighborhood.

- 3 Energy retrofitting is legally interpreted as improving the rental object and thus counts as a modernization measure. According to a study by the Berlin tenants’ association Berliner Mieterverein, in nearly all of the cases of modernization it reviewed, it was the energy measures undertaken that contributed most to rent increases (BMV, 2017).

- 4 Bürgergeld, or ‘citizen's income’, is a transfer payment for unemployed people (formerly ‘Hartz IV’).