Determinants of IPO Overpricing

Abstract

This paper outlines the phenomenon of negative first-day IPO returns. Using a comprehensive sample of IPOs in the United States between 2000 and 2020, we find that 21.61% exhibit negative first-day returns, making this a common feature of the US IPO market. The key findings show that the IPO mechanism is important. A larger deal size and proportion of over-allotment shares reduces the probability of IPO overpricing, while downward offer price adjustments increase the likelihood of negative first-day returns. Despite distinct differences, the analysis reveals shared characteristics between IPO underpricing and overpricing, providing nuanced insights into IPO pricing. Neither market timing nor agency issues significantly affect IPO overpricing.

Introduction

Initial public offerings (IPOs) mark a company's transition from private to public and require strategic pricing and marketing to potential investors (Beatty and Ritter, 1986; Guo, 2011; Ritter, 1987; Zingales, 1995). IPOs are often motivated by the need to secure funds for future growth and value creation (Lowry and Schwert, 2004). The IPO process involves many parties and does not always go according to plan (Helbing, Lucey and Vigne, 2019). The Uber IPO in May 2019 attracted investors despite criticism over continuous losses, yet it debuted with a negative first-day return of 7.6% (Franklin, Saxena and Somerville, 2019). While IPO underpricing is well studied (Aggarwal, Krigman and Womack, 2002; Ritter and Welch, 2002), our motivation to focus on overpricing stems from the need for a holistic comprehension of IPO pricing. Overpricing potentially risks investor wealth, market efficiency and reputational integrity, especially during market exuberance. Managers must comprehend these IPO pricing nuances due to their strategic impact on firm value maximization.

Our study encompasses 2111 US firms listed from 2000 to 2020 and reveals an average positive first-day IPO return of 21.11%, consistent with prior findings. However, we observe a significant 21.27% of IPOs with negative first-day returns, sparking our research question: What influences negative first-day IPO returns? Despite focusing on the United States, our results bear international significance. By 2020, the United States made up around 47% of the global IPO market, meaning that US IPO patterns can heavily influence global trends, enriching the global IPO pricing strategies discourse.

We scrutinize IPO overpricing's extent and determinants by employing univariate, linear and probability analyses. Our findings highlight that IPO overpricing likelihood increases by 48% if the IPO's opening price falls below the prospectus's offer price. Conversely, a greenshoe option, especially more over-allotment shares, brings post-listing price stability, decreasing the likelihood of negative first-day returns by 49%. Ex-ante uncertainty and information asymmetries between the IPO company and investors crucially affect overpricing. Larger deals show a reduced chance of first-day negative returns. Against expectations, tech sector affiliation reduces the chance of negative first-day returns. We found no significant impact on overpricing from market conditions, underwriter certification or corporate governance. When examining the overpricing sample, we found that firm characteristics like venture capital (VC) backing and auditor quality significantly increase the overpricing extent, while Nasdaq listing can decrease it. These patterns persist in 5-day returns.

This paper sheds light on the extent and determinants of IPO overpricing. Our study offers several key contributions. First, to the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to uniquely focus on negative first-day returns, offering extensive empirical evidence on this unexplored aspect of IPO pricing. Second, we utilize a sample of 2111 IPO firms supplemented by hand-collection listed on the US stock exchanges from 2000 to 2020, providing a robust foundation for our analysis. Third, we identify common determinants impacting the probability of IPO overpricing. We contrast these with what is already known about IPO underpricing, enriching academic discourse and offering actionable insights for global practitioners, academics, underwriters, investors and IPO firms.

Our findings can help these stakeholders navigate the IPO process better and minimize the likelihood of negative first-day returns, enhancing financial markets' overall efficiency and stability. Overpricing could lead to investor wealth losses, reduced market efficiency, reputational damage for the issuing firm and underwriters and lower aftermarket liquidity. Investors participating in an overpriced IPO might experience immediate losses when the stock price declines on the first trading day. Conversely, several potential positive aspects could be associated with negative first-day IPO returns. First, overpricing might result in a more realistic market valuation, benefiting the firm's long-term financial sustainability. Second, the drop in stock price could create an attractive entry point for new investors, possibly providing a better risk–reward ratio for those who did not participate in the IPO or were initially sceptical of the company's valuation. Third, overpriced IPOs that experience negative first-day returns may attract enhanced scrutiny and accountability. Finally, negative first-day returns could be a valuable learning experience for issuers and underwriters, encouraging refinements to pricing models, due diligence processes and overall IPO strategies. A comprehensive understanding of these consequences is essential for stakeholders to navigate the IPO process better and develop effective pricing strategies.

First-day IPO returns

The IPO literature has extensively analysed underpricing, but not overpricing. Despite studies implicitly broaching this subject (Ber, Yafeh and Yosha, 2001; Boulton, Smart and Zutter, 2020; Ritter and Welch, 2002), an explicit exploration into the specific determinants of such adverse outcomes remains sparse. Global explorations of overpricing further underscore the extent of this phenomenon. Notably, Ritter and Welch (2002) found that while underpricing occurred in 18.8% of US IPOs from 1980 to 2001, a striking 30% of these demonstrated negative first-day returns. Overpricing has been observed across a wide array of markets, with Agustina and Clara (2021) reporting an average of 25.19% in Indonesia, while Rathnayake et al. (2019) identified IPO overpricing between 17% and 18% in Sri Lanka. Persistent overpricing was a characteristic of Israel's IPO market during the 1990s (Ber, Yafeh and Yosha, 2001), and in the Australian market, overpricing rates hovered around 1.54% and 1.55% (Perera and Kulendran, 2016). In Malaysia, a higher proportion of overpriced IPOs are allocated to institutional investors (Howton, Howton and Olson, 2001). These instances underscore the prevalence of overpricing globally, challenging the established norm of underpricing, and necessitate a deeper understanding of the phenomenon.

Yet, despite compelling international evidence, dedicated studies on IPO overpricing remain absent. This lacuna in the scholarship assumes heightened importance, considering the economic implications of overpricing and the pivotal role of the United States in the global IPO landscape. Thus, we must explore this uncharted territory and investigate the determinants contributing to negative first-day returns, focusing specifically on US IPOs. Through this study, we aspire to enhance our understanding of IPO pricing strategies, furnish critical insights that bear global relevance and unravel the intricate layers of IPO overpricing.

As no concrete theoretical framework exists for overpricing, we will rely on insights from the underpricing literature. Despite underpricing and overpricing representing contrasting outcomes, both indicate IPO pricing process inefficiencies. By analysing the theoretical underpinnings and empirical findings on underpricing, we aim to identify potential parallels and divergences that can be applied to overpricing, thereby constructing a cohesive theoretical framework for our investigation.

IPO pricing presents a dilemma due to the absence of a pre-existing market price and limited historical data on the issuing company (Ibbotson, Sindelar and Ritter, 1994). This leads to heightened valuation uncertainty, corresponding to higher first-day returns as investors grapple with the accurate value of the newly issued shares (Beatty and Ritter, 1986; Loughran and McDonald, 2013; Loughran, Ritter and Rydqvist, 1994). On the one hand, to reduce the risks of IPO withdrawal or inadvertent overpricing, the offer price is often set lower than market expectations (Lowry, Officer and Schwert, 2010). This has led to the ‘underpricing puzzle’ concept in the IPO literature (Ibbotson, 1975; Logue, 1973; Ritter and Welch, 2002; Stoll and Curley, 1970). On the other hand, in particular circumstances, notably when pre-market demand is weak and the threat of IPO withdrawal is significant, underwriters might deliberately increase the offer price (Busaba, Liu and Restrepo, 2020). Therefore, the decision to underprice or overprice an IPO, and its subsequent impact on first-day returns, is a complex process influenced by factors such as demand, market conditions and strategic considerations by the underwriters.

Asymmetric information theory

Theories explaining first-day returns often pivot around information asymmetries between IPO firms, financial intermediaries and potential investors (Baker and Gompers, 2003; Ljungqvist, Nanda and Singh, 2006). Benveniste and Spindt (1989) and Spatt and Srivastava (1991) investigate these asymmetries during book-building, when information about demand and IPO companies emerges. Though book-building only explains a small percentage of underpricing (Brau and Fawcett, 2006; Loughran and Ritter, 2002), underwriters often utilize their market knowledge to strategically underprice IPOs, reducing marketing efforts (Baron and Holmstrom, 1980; Ritter and Welch, 2002). This gap in information can lead to a misalignment between IPO pricing strategies and the market's capacity to support the price once trading begins. Interestingly, the same information asymmetries contributing to underpricing can engender overpricing. For instance, underwriters might overestimate the IPO demand, resulting in an inflated offer price (Beatty and Ritter, 1986; Rock, 1986).

Ex-ante uncertainty plays a critical role in both underpricing and overpricing. It is linked to greater underpricing to compensate risk-bearing investors, with factors such as investment banking reputation, the ‘winner's curse’ and ownership dispersion contributing to valuation uncertainty (Beatty and Ritter, 1986; Booth and Chua, 1996; Ritter, 1984; Rock, 1986). Conversely, high ex-ante uncertainty can incite overpricing when underwriters overestimate the firm's future cash flow potential, culminating in an inflated offer price and subsequent market adjustment (Signori, 2018).

Small-firm effect

The ‘small-firm effect’ initially observed by Banz (1981) and Blume and Stambaugh (1983) concludes that smaller companies generate higher risk-adjusted returns compared to their larger counterparts. Ritter (1984), Lowry, Officer and Schwert (2010) and Signori (2018) noted that smaller companies, which often face more substantial ex-ante uncertainty, are typically more underpriced. These firms must generate higher returns to compensate for this increased risk, as suggested by Beatty and Ritter (1986) and Rock (1986). However, the scope of the small-firm effect extends beyond underpricing. Lowry, Officer and Schwert (2010) pointed out that optimism from investors and underwriters may lead to overestimating these smaller companies' valuations during the IPO process. As more information becomes available, the market valuation may be adjusted downwards (Signori, 2018), leading to negative first-day returns. Thus, the small-firm effect can steer IPO market pricing towards underpricing and overpricing.

Signalling theory

Signalling theory, widely utilized to elucidate IPO underpricing, hinges on specific mechanisms acting as quality signals to reduce information asymmetries (Booth and Smith, 1986). Underwriters function as such signals, often necessitating IPO underpricing to safeguard their market reputation (Carter and Manaster, 1990; Lee, Taylor and Walter, 1999). VC backing signals quality and mitigates uncertainty and adverse selection concerns (Akerlof, 1970; Megginson and Weiss, 1991). Reputable auditors can be an additional certification (Beatty and Ritter, 1986; Peng et al., 2021). Critiques of signalling theory suggest limitations (Espenlaub and Tonks, 1998; Gale and Stiglitz, 1989; Ritter, 2011). The implications of signalling theory are not confined to underpricing; they may also account for overpricing scenarios. A lack of robust signals or inaccurate signalling can lead to overvaluation. For example, weak or unfavourable signals might prompt investors to overestimate the firm's prospects, resulting in an overpriced IPO. Firms may also strategically distort these signals to project an inflated image of quality, leading to an initial overvaluation corrected by market forces, resulting in negative first-day returns (Kennedy, Sivakumar and Vetzal, 2006). Therefore, while signalling theory is typically associated with underpricing, it can also offer valuable insights into the phenomenon of IPO overpricing.

IPO pricing dynamics

The dynamics of IPO pricing, particularly during the pre-IPO period, involve investment bankers adjusting their valuation expectations based on emerging information. An empirical relationship between first-day returns and the change in the offer price, known as partial adjustment, was first established by Hanley (1993) and is supported by the model proposed by Benveniste and Spindt (1989). Investors who candidly disclose their demand during the book-building process would be compensated with increased underpricing, leading to an incomplete adjustment of the offer price in response to private, firm-specific information (Hanley, 1993; Loughran and Ritter, 2002). The price stabilization hypothesis, developed by Booth and Smith (1986) and later elaborated by Benveniste and Busaba (1997), argues that financial intermediaries, such as underwriters, employ greenshoe options to dynamically stabilize supply and demand (Asquith, Jones and Kieschnick, 1998). This model was empirically expanded by Benveniste and Spindt (1989) to incorporate over-allotment, which disincentivizes early issue selling by underwriters and encourages information gathering from investors. Partial adjustments and greenshoe options can contribute to overvaluation. If investment bankers adjust their expectations upwards due to excessive pre-IPO demand or optimism, this may lead to an overpriced offer. Similarly, a less significant change in the offer price due to greenshoe options might compound overpricing if underwriters do not adequately respond to market sentiment or new information. As market participants reassess the firm's prospects, this overvaluation may be rectified, leading to negative first-day returns.

Market sentiment

Market sentiment, particularly optimism, has been implicated in pricing IPOs through market timing explanations, wherein underwriters might set an elevated issue price exploiting buoyant investor sentiment (Derrien, 2005). Ljungqvist, Nanda and Singh (2006) and Chemmanur and He (2011) highlight that especially during ‘hot markets’, investor optimism often escalates, leading to higher underpricing; a view embodied in the ‘window of opportunity’ hypothesis. However, market dynamics can also influence overpricing. Contrary to underpricing in ‘hot markets’, periods of market pessimism or investor caution could precipitate overpricing as underwriters may inflate the issue price to compensate for anticipated lower demand. Similarly, firms aspiring to debut during favourable market conditions may inadvertently contribute to overpricing if market conditions or sentiment suddenly deteriorate. The market adjustment to the firm's actual value might lead to negative first-day returns in such cases.

Overpriced IPOs: A new lens

We take these underlying theoretical concepts and empirical evidence on IPO underpricing to identify factors impacting negative first-day IPO returns. We can sub-divide these factors into broad categories: IPO mechanism, corporate governance, firm-specific and market characteristics. The measures used to represent and proxy the determinants of negative first-day IPO returns are outlined in Table A.1 in the Online Appendix.

First, we consider specific IPO mechanism characteristics to approximate ex-ante uncertainty and pre-IPO market demand. Previous studies, such as Booth and Chua (1996), suggest that the offer price is a proxy for uncertainty about the firm's value. If the offer price increases, the expected magnitude of undervaluation decreases. Hanley (1993) presents empirical evidence of partial adjustments to the final offer price; thus, issuers update their offer prices based on information about investor demand. Issues for which there is weak pre-market demand are adjusted downwards in price and less undervalued due to lower oversubscription and overall information costs. We assume lower offer prices are associated with increased uncertainty, leading to negative first-day returns. We also introduce the offer-to-first-open dummy. According to Nielsson and Wójcik (2016), the corrections can also be seen as a reflection of changes in investor attention and subsequent demand. As there is uncertainty on the actual listing date of the IPO, we assume that an opening price below the offer price increases uncertainty and leads to negative first-day returns. We add a below–range dummy because the ratio between the final offer price and the range of expected offer prices indicated in the preliminary prospectus is a good predictor of the extent of valuation on the first trading day (Benveniste and Spindt, 1989; Hanley, 1993; Loughran and Ritter, 2002). Consistent with Hanley (1993) and Loughran and Ritter (2002), we expect IPOs with downward adjustments to have lower first-day returns. Consistent with the price support hypothesis, the greenshoe option stabilizes the aftermarket to price and demand fluctuations with greater flexibility (Benveniste and Busaba, 1997). We conjecture that with larger available over-allotment options, overpricing and underpricing are more prevalent (Hanley, 1993). Potentially, price support limits cascading effects that potentially cause downward spirals in stock prices (Welch, 1992). Thus, we assume that the likelihood of negative first-day returns decreases with an increased percentage of over-allotment options (Aggarwal, Krigman and Womack, 2002; Ellis, Michaely and O'Hara, 2000). The IPO waiting period classifies the length between IPO announcement and first trading date (Chowdhry and Sherman, 1996; Francis et al., 2010). We assume that longer waiting periods induce uncertainty about the prospect of the IPO company and thus increase the probability of IPO overpricing.1

- H1: Better IPO mechanism characteristics reduce the likelihood of negative first-day returns.

- H2: Better corporate governance characteristics decrease the likelihood of first-day returns.

- H3: Smaller and younger IPO firms are more likely to experience negative first-day returns.

- H4: Better market characteristics reduce the likelihood of negative first-day returns.

Data and method

Data

This paper examines all common stock IPOs in the United States between January 2000 and December 2020, covering a 20-year time window. Thus, we exclude American Depository Receipts, closed-end or mutual funds, special-purpose entities, rights issuance and Real Estate Investment Trusts. Firms operating in the financial and real estate sector and offerings with a price below are removed from the sample (Ritter, 1987; Ritter and Welch, 2002). Based on the Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS), the sample is divided into nine sectors: energy, materials, consumer discretionary, consumer staples, healthcare, information technology, telecommunications and utilities. As a first instance, Bloomberg is used to obtain a sample of 1935 IPOs. Then, by adding IPO data from other data providers such as S&P Capital IQ,2 the existing sample is supplemented by 176 companies, resulting in a total sample of 2111 IPOs. In our sample, 1543 (73.09%) IPOs have positive and 119 (5.64%) IPOs have absolute zero first-day returns.3 A substantial number of IPOs in our sample, 449 (21.27%), exhibit negative first-day returns. The sample has an average first-day return of 21.11% (median 10%) with a minimum value of −99.86% and a maximum value of 370.78%.

For firm- and offer-specific characteristics, we retrieve, cross-check and manually add missing data where necessary from S-1 prospectuses, Refinitiv, Bloomberg and PitchBook. For the corporate governance characteristics, we mainly used BoardEx data but also extracted and supplemented many of these variables from the IPO prospectuses. The variables of the market characteristics are broadly retrieved from the Federal Reserve Bank St. Louis (see Table A.1 in the Online Appendix). Owing to the large number of hand-collected variables, our data set is unique in scope, comprehensiveness and depth. Our data set spans 20 years, from 2000 to 2020. With the start of a new millennium, IPOs have declined, and cycles are more muted compared to the late 1990s and 1980s (Lowry, Michaely and Volkova, 2017). Nonetheless, we include the dot.com bubble in our research to analyse market hotness and crisis periods.

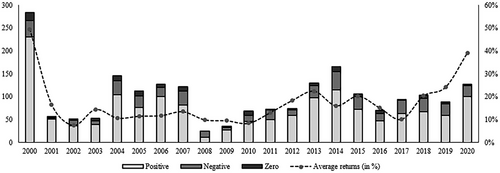

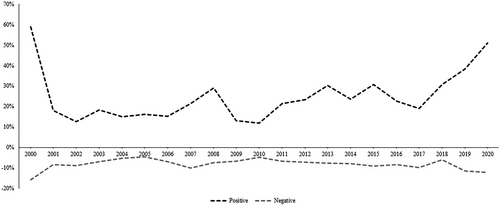

Figure 1 shows the changing IPO volume in the United States and the emergence of negative first-day returns across time. In 2000, we can observe the largest share of the total sample with 284 firms and the highest proportion of average first-day return of 49.43%. In contrast, in 2008, we can observe the lowest number with 25 IPOs and some of the lowest average first-day returns of 9.98%. IPOs appear to be especially highly underpriced when markets are ‘hot’ (Loughran and Ritter, 2002). The wave-like nature of IPOs becomes evident; a high average first-day return seems to go hand in hand with high volume in the entire market (Ritter and Welch, 2002), as can be seen for example in 2000, 2004 and 2014. The proportion of negative initial returns is frequently occurring yet changing each year. We can observe the highest levels in 2004, 2007 and 2014, while the proportion of negative first-day IPOs exceeded underpriced IPOs in 2008, possibly given the heightened uncertainty in the market in the wake of the global financial crisis. Figure 2 shows each sector category's negative and positive share. The materials sector has the largest negative first-day return, at 29.41%, closely followed by the telecommunications sector at 26.04%. The consumer staples and IT sectors have the lowest negative first-day returns of 15.25% and 15.29%, respectively. The primary finding is that negative first-day IPO returns are present in every sector. Furthermore, our sample of negative and positive first-day returns is relatively evenly distributed across sectors. Figure 3 shows that the average positive first-day return ranges from 11.30% in 2010 to 58.89% in 2000, whereas the negative average first-day return ranges from −4.65% in 2005 to −15.72% in 2000. The average first-day return of the entire positive sample is 24.79%, while that of the entire negative sample is −8.20%.

Method

In our model, are the independent variables in Table A.1 in the Online Appendix, with the respective beta coefficients under the cumulative normal distribution. To interpret our results, we compute marginal effects (ME), which depict the average change in when increases by one unit. In the primary probability setting, our dependent variable is a dummy variable that takes the value 1 if the IPO has a negative first-day return, and 0 otherwise.

The determinants of negative first-day IPO returns

Descriptive analysis

As a preliminary investigation, Table 1 reports the mean and standard deviation of the variables by first-day return outcome.4 We also provide a test for differences in means across positive and negative first-day IPO returns.

| Positive first-day IPO returns | Negative first-day IPO returns | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | µ | µ | t-test | p-value | ||

| IPO Mechanism | ||||||

| Offer Price | 15.18 | 6.37 | 12.79 | 5.20 | 7.31 | 0.0000 |

| Deal Size (in million) | 253 | 868 | 177 | 434 | 1.81 | 0.0713 |

| Offer-To-First-Open | 0.033 | 0.177 | 0.503 | 0.501 | −31.70 | 0.0000 |

| Below-Range Dummy | 0.123 | 0.328 | 0.410 | 0.492 | −14.62 | 0.0000 |

| Greenshoe Option | 0.150 | 0.033 | 0.141 | 0.045 | 5.08 | 0.0000 |

| IPO Waiting Period | 83 | 87 | 91 | 143 | −1.56 | 0.1194 |

| Nasdaq Dummy | 0.715 | 0.452 | 0.695 | 0.461 | 0.83 | 0.4090 |

| Underwriter Rank | 7.464 | 1.756 | 6.909 | 2.170 | 5.64 | 0.0000 |

| Primary Shares | 0.570 | 0.339 | 0.574 | 0.328 | −0.19 | 0.8508 |

| Corporate Governance | ||||||

| Board Size | 7 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 1.84 | 0.0664 |

| Female Ratio | 0.090 | 0.114 | 0.084 | 0.121 | 0.87 | 0.3845 |

| Succession Rate | 0.523 | 0.218 | 0.494 | 0.226 | 2.49 | 0.0130 |

| Network Size | 1346 | 1500 | 1191 | 1296 | 2.00 | 0.0453 |

| CEO Age | 51 | 8 | 51 | 9 | 0.05 | 0.9585 |

| CEO Duality | 0.251 | 0.434 | 0.256 | 0.437 | −0.23 | 0.8212 |

| Firm Characteristics | ||||||

| Company Age | 17 | 24 | 18 | 27 | −0.82 | 0.4148 |

| Private Equity | 0.288 | 0.453 | 0.283 | 0.451 | 0.22 | 0.8239 |

| Auditor | 0.818 | 0.386 | 0.693 | 0.462 | 5.86 | 0.0000 |

| Venture Capital | 0.509 | 0.500 | 0.490 | 0.500 | 0.72 | 0.4741 |

| IT | 0.290 | 0.454 | 0.194 | 0.396 | 4.09 | 0.0000 |

| Firm Size | 794 | 4257 | 738 | 2538 | 0.27 | 0.7905 |

| Leverage | 0.415 | 0.929 | 0.601 | 1.202 | −3.51 | 0.0005 |

| Return on Assets | −0.241 | 0.860 | −0.510 | 1.378 | 5.09 | 0.0000 |

| Market Conditions | ||||||

| Crisis | 0.040 | 0.195 | 0.036 | 0.186 | 0.04 | 0.6918 |

| VIX | 18.231 | 6.145 | 17.647 | 6.234 | 1.78 | 0.0749 |

| ΔInterest Rate | 0.007 | 0.098 | 0.006 | 0.070 | 0.28 | 0.7767 |

| ΔGDP | 0.012 | 0.017 | 0.012 | 0.014 | −0.07 | 0.9451 |

| ΔIndex | 0.007 | 0.038 | 0.011 | 0.035 | −2.06 | 0.1583 |

| Hotness Dummy | 0.539 | 0.499 | 0.597 | 0.49 | −2.19 | 0.0290 |

| N | 1662 | 449 | ||||

- Note: This table reports the difference in means and associated p-values. The difference is taken as the mean of the positive first-day IPO returns sample less the mean of the negative first-day IPO returns sample. Therefore, positive differences (and associated t-statistics) represent a larger mean value for the underpriced IPO sample, whereas a negative difference (and associated t-statistics) represents a larger mean value for the overpriced IPO sample. The table uses the following abbreviations: µ represents the mean and denotes the standard deviation. Included in the sample are 1662 IPOs with positive first-day returns and 449 IPOs with negative first-day returns.

We find some evidence for heightened uncertainty of future cash flows for smaller IPOs with less information provision. IPOs with negative first-day returns have significantly lower offer prices and smaller deal sizes. As expected, weak market demand is more pronounced for overpriced IPOs. The offer-to-first-open dummy and the below-range dummy, approximating downward price adjustments, are significantly larger for IPOs with negative first-day returns than their underpriced issues. A significantly larger proportion of greenshoe options can be observed for positive first-day IPO returns stabilizing aftermarket demand. IPO firms with negative first-day returns have one or more underwriters on board with a significantly lower ranking than their underpriced counterparts. There is no significant difference in IPO companies' stock exchange, IPO waiting period or share structure. While IPOs with negative first-day returns have statistically significantly smaller board sizes, on average, both outcomes have seven board members; hence, this does not provide compelling economic evidence. We find a significantly smaller network among firms with negative first-day IPO returns. Using the succession rate, we can observe that firms with negative first-day IPO returns have significantly fewer directors of retirement age than those with positive returns at the close of the first trading day. There is no difference in the proportion of female board members, CEO age or CEO duality. Companies with negative first-day returns have significantly higher leverage and lower return on assets. We cannot observe a significant difference in company age or firm size across outcomes, although the latter is economically smaller on average for overpriced IPOs. Big Four auditors are less frequently supporting IPO firms with negative first-day returns. However, there is no statistical difference in PE or VC involvement. A lower proportion of IPO companies from the technology sector report negative first-day returns. Finally, for market characteristics, we cannot find significant differences across IPO returns. Negative first-day IPO returns exhibit less volatile market conditions (VIX) with ‘hotter’ markets. This seems intuitive with market timing ideas, as in more volatile and ‘hotter’ markets, IPOs are more underpriced (Ibbotson, 1975). However, other market timing-based variables do not show any significant results. In summary, the descriptive analysis reflects the effect of market demand and existing information asymmetries between the different IPO parties. Overpriced IPOs are smaller, adjust their prices downward, have fewer greenshoe options, have less reputable underwriters and auditors and show worse financials.

General findings

Table 2 shows the results of the probit analysis together with the coefficients, corresponding p-values and ME. We add the different categories of variables to the model, respectively. We specify Model 1 with only IPO mechanism characteristics; in Model 2 we add corporate governance characteristics, in Model 3 firm characteristics and finally in Model 4 market characteristics.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coeff. | p-value | Marginal effect | coef. | p-value | Marginal effect | coeff. | p-value | Marginal effect | coef. | p-value | Marginal effect |

| IPO Mechanism | ||||||||||||

| Offer Price | −0.1447 | 0.2690 | −0.0363 | −0.1540 | 0.2410 | −0.0385 | −0.1421 | 0.2830 | −0.0353 | −0.1514 | 0.2550 | −0.0375 |

| Deal Size | −0.1621 | 0.0030 | −0.0407 | −0.1509 | 0.0080 | −0.0378 | −0.1357 | 0.0280 | −0.0337 | −0.1345 | 0.0300 | −0.0333 |

| Offer-To-First-Open | 1.9512 | 0.0000 | 0.4898 | 1.9485 | 0.0000 | 0.4876 | 1.9338 | 0.0000 | 0.4798 | 1.9332 | 0.0000 | 0.4784 |

| Below-Range Dummy | 0.6703 | 0.0000 | 0.1683 | 0.6756 | 0.0000 | 0.1691 | 0.6957 | 0.0000 | 0.1726 | 0.6993 | 0.0000 | 0.1730 |

| Greenshoe Option | −2.0636 | 0.0340 | −0.5180 | −2.0508 | 0.0350 | −0.5132 | −2.0427 | 0.0390 | −0.5068 | −1.9788 | 0.0470 | −0.4897 |

| IPO Waiting Period | 0.0000 | 0.9720 | 0.0000 | −0.0001 | 0.8510 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.9160 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | 0.7910 | 0.0000 |

| Nasdaq Dummy | −0.0574 | 0.5090 | −0.0144 | −0.0453 | 0.6040 | −0.0113 | −0.0701 | 0.4510 | −0.0174 | −0.0646 | 0.4900 | −0.0160 |

| Underwriter Rank | −0.0070 | 0.7570 | −0.0018 | −0.0064 | 0.7820 | −0.0016 | 0.0124 | 0.6130 | 0.0031 | 0.0134 | 0.5880 | 0.0033 |

| Primary Shares | 0.0133 | 0.9060 | 0.0033 | 0.0212 | 0.8510 | 0.0053 | 0.0393 | 0.7300 | 0.0098 | 0.0441 | 0.7010 | 0.0109 |

| Corporate Governance | ||||||||||||

| Board Size | 0.0142 | 0.4980 | 0.0036 | 0.0119 | 0.5740 | 0.0030 | 0.0114 | 0.5920 | 0.0028 | |||

| Female Ratio | −0.1441 | 0.6480 | −0.0361 | −0.2147 | 0.5020 | −0.0533 | −0.1938 | 0.5460 | −0.0480 | |||

| Succession Rate | −0.2814 | 0.1010 | −0.0704 | −0.2427 | 0.1710 | −0.0602 | −0.2394 | 0.1790 | −0.0592 | |||

| Network Size | −0.0285 | 0.2280 | −0.0071 | −0.0333 | 0.1680 | −0.0083 | −0.0355 | 0.1430 | −0.0088 | |||

| CEO Age | −0.1514 | 0.4740 | −0.0379 | −0.1479 | 0.5010 | −0.0367 | −0.1577 | 0.4750 | −0.0390 | |||

| CEO Duality | 0.0134 | 0.8720 | 0.0034 | 0.0338 | 0.6890 | 0.0084 | 0.0224 | 0.7940 | 0.0055 | |||

| Firm Characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Company Age | −0.0547 | 0.1530 | −0.0136 | −0.0565 | 0.1430 | −0.0140 | ||||||

| Private Equity | 0.0728 | 0.5250 | 0.0181 | 0.0691 | 0.5480 | 0.0171 | ||||||

| Auditor | −0.1584 | 0.1020 | −0.0393 | −0.1553 | 0.1110 | −0.0384 | ||||||

| Venture Capital | 0.1219 | 0.2230 | 0.0302 | 0.1178 | 0.2400 | 0.0292 | ||||||

| IT Dummy | −0.1732 | 0.0490 | −0.0430 | −0.1570 | 0.0780 | −0.0389 | ||||||

| Firm Size | 0.0044 | 0.8650 | 0.0011 | 0.0040 | 0.8770 | 0.0010 | ||||||

| Leverage | 0.0509 | 0.1390 | 0.0126 | 0.0474 | 0.1700 | 0.0117 | ||||||

| Return on Assets | −0.0648 | 0.0760 | −0.0161 | −0.0629 | 0.0880 | −0.0156 | ||||||

| Market Conditions | ||||||||||||

| Crisis | 0.1329 | 0.5220 | 0.0329 | |||||||||

| VIX | −0.1451 | 0.2760 | −0.0359 | |||||||||

| ΔInterest Rate | −0.0901 | 0.8500 | −0.0223 | |||||||||

| ΔGDP | 0.5835 | 0.8090 | 0.1444 | |||||||||

| ΔMarket Index | 1.3825 | 0.1890 | 0.3421 | |||||||||

| Hotness Dummy | 0.0599 | 0.4280 | 0.0148 | |||||||||

| Mc Fadden's Adj. R2 | 0.3030 | 0.3000 | 0.3010 | 0.2980 | ||||||||

| Hosmer–Lemeshow | 14.05 | 25.44 | 17.21 | 21.62 | ||||||||

| N | 2111 | 2111 | 2111 | 2111 | ||||||||

- This table shows the results of four probit models. The dependent variable is a dummy variable that takes the value one if the IPO has a negative first-day return on the first day and zero otherwise. The independent variables are divided into IPO mechanism characteristics, corporate governance characteristics, firm characteristics, and market conditions. In Model 1, only the IPO mechanism characteristics are considered. In Model 2, the corporate governance characteristics are also considered. While Model 3 also considers company characteristics, Model 4 considers all variables together. Robust standard errors are included in our analysis. Average Marginal Effects are defined as follows: the Probit employs normalisation that fixes the standard deviation of the error term to 1, where each coefficient represents the average marginal effect of a unit change on the probability that the dependent variable takes the value of either 0 or 1 given that all other independent variables are constant. The matched sample includes 2,111 observations. The McFadden R-squared is defined as 1 less the log-likelihood for the estimated model divided by the log-likelihood for a model with only an intercept as the independent variable. While the Hosmer-Lemeshow Statistic represents the goodness of fit that observed events match estimated events in ten subgroups of the model population.

We find evidence for the importance of pre-IPO market demand. Partial price adjustments are related to changes in underpricing (Hanley, 1993). We find evidence for its importance on overpricing as the probability of negative first-day returns is increased by 16.83% (p-value = 0.0000) when the offer is priced below the offer range. This is significant across all four models. Negative offer price corrections seem to impact the overpricing phenomenon significantly. Following Benveniste and Spindt (1989)'s partial adjustment model, unfavourable information and low demand in the pre-issue period can result in the offer price being adjusted downwards. Loughran and Ritter (2002) found that offer prices adjusted downwards were less severely underpriced than those adjusted upwards. We extend this finding to IPO overpricing. More greenshoe options are generally seen as adding to post-listing price stability. We can observe a reduced probability of negative first-day returns by 51.80% (p-value = 0.0340). This finding is as expected, as previous evidence has found a negative relationship between greenshoe option and IPO underpricing (Aggarwal, Krigman and Womack, 2002; Ellis, Michaely and O'Hara, 2000). We can extend this finding to IPO overpricing as well. The possible after-market price stabilization mechanism with the help of the greenshoe option on the part of the underwriters seems to be a powerful tool (Benveniste and Busaba, 1997). Furthermore, deal size is vital to the IPO overpricing phenomenon (ME = −4.07%, p-value = 0.0030). We find evidence for heightened uncertainty of future cash flows for smaller IPOs with less information provision (Beatty and Ritter, 1986; Bradley et al., 2006; Chalk and Peavy, 1987). The smaller the deal size of an issuing company, the higher the probability that this company will close with a negative return on the first trading day. These findings are consistent across all models. We can infer that larger offerings are mainly made by mature and established companies, whereas speculative companies mainly make smaller offerings with uncertain cash flows; thus, the asymmetric information between the IPO company and potential investors plays a key role (Beatty and Ritter, 1986). While ex-ante uncertainty is an essential determinant of underpricing, this also holds for overpricing. We find evidence for prevailing information asymmetries between the issuing firm and potential investors in pricing, as the probability of negative first-day returns is increased by about 48.98% (p-value = 0.0000) when the opening price is below the offer price at the stock market debut. In summary, these findings provide compelling evidence in favour of H1. A better IPO mechanism, approximated by deal size and greenshoe options, as well as pricing characteristics, such as offer price to first open or the below-range dummy, are important in determining IPO overpricing. Other variables in this category do not show statistical significance, but the expected direction of effect.

We include corporate governance variables, however we cannot identify any effect on negative first-day IPO returns. Agency-related variables do not seem to impact the overpricing phenomenon significantly. Contrary to our expectations, we do not find evidence in favour of H2. These results are surprising, as previous research has identified a significant relationship between corporate governance and IPO underpricing (Chiraz and Jarboui, 2016; Feng, Song and Tian, 2019). This does not hold for IPO overpricing.

With respect to firm-specific characteristics, technology IPOs are associated with higher information asymmetry. Hence they, are more underpriced, as shown theoretically in Rock (1986) and empirically in Michaely and Shaw (1994). Engelen and van Essen (2010) assume that the degree of pre-IPO uncertainty tends to be more pronounced for technology firms. We confirm this finding, as the technology sector significantly decreases the probability of IPO overpricing by 4.30% (p-value = 0.0490). The certification function, especially the auditor's quality, also influences the probability of negative first-day returns, but only shows weak statistical significance. As examined by Beatty and Ritter (1986) for underpricing, IPOs that use lower-quality auditors have higher positive first-day returns; while we find economic evidence for this finding, we cannot demonstrate this statistically. Following the idea of Koop and Li (2001), who found increased underpricing in IPOs with low earnings potential; we can identify a negative, statistically significant coefficient (ME = −1.61%, p-value = 0.0760). The higher the earnings potential, the lower the probability of negative first-day IPO returns. Other variables that have been evidenced to influence IPOs, such as VC or PE, are insignificant. The absence of a significant relationship might indicate that ‘smart capital’ can appropriately price the IPO (Gerasymenko and Arthurs, 2014). We do not find statistical evidence supporting H3; while older firms exhibit a negative yet insignificant effect, the firm size is of no importance. We conclude that especially IPO mechanism characteristics determine the probability of IPO overpricing, whereas firm characteristics play a secondary role; much in contrast to previous evidence on IPO underpricing (see e.g. Engelen and van Essen, 2010; Ritter and Welch, 2002). This again highlights the difference between under- and overpriced IPOs.

Finally, due to the cyclical nature of the IPO market, it is considered in many respects to be sentiment-driven (Baker and Gompers, 2003); we find significant pre-IPO market demand variables. Notwithstanding, in contrast H4, we cannot identify a significant impact of market conditions on the probability of IPO overpricing.

In summary, we confirm and extend existing knowledge about IPO underpricing to IPO overpricing and identify the main determinants of first-day negative IPO returns. Greenshoe options effectively stabilize the IPO, as a higher proportion of over-allotment shares significantly decrease negative first-day IPO returns. The probability of IPO overpricing is significantly increased when the offer price is higher than the first open price and when prices are further adjusted downwards. A higher deal size and technology dummy significantly decrease the probability of IPO overpricing. Contrary to our expectations, we cannot find statistical evidence favouring market-timing ideas or the importance of agency issues on the IPO overpricing phenomenon. We can only find compelling evidence in support of H1, manifesting the importance of the IPO mechanisms in determining first-day negative returns.

Additional analyses

To further explore the extent of IPO overpricing, we include alternative specifications in Table 3. In Model 1, we add the observations with zero first-day IPO returns (119) to the negative first-day IPO returns sample. We want to check whether our results still hold, examining all IPOs that are not underpriced (zero and negative first-day IPO returns). In Model 2, we exclude the 25th percentile of the overpriced sample to identify differences across underpriced and moderately overpriced IPOs. Thus, the most overpriced IPOs (113, average −20%) are removed from the sample. In Model 3, we exclude all zero first-day IPOs (119).

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coeff. | p-value | Marginal effect | Coeff. | p-value | Marginal effect | Coeff. | p-value | Marginal effect |

| IPO Mechanism | |||||||||

| Offer Price | −0.2463 | 0.0480 | −0.0751 | −0.1839 | 0.2040 | −0.0366 | −0.1733 | 0.2080 | −0.0448 |

| Deal Size | −0.1709 | 0.0040 | −0.0521 | −0.0754 | 0.2600 | −0.0150 | −0.1730 | 0.0070 | −0.0448 |

| Offer-To-First-Open | 1.8343 | 0.0000 | 0.5597 | 1.8055 | 0.0000 | 0.3598 | 2.0109 | 0.0000 | 0.5204 |

| Below-Range Dummy | 0.7971 | 0.0000 | 0.2432 | 0.7935 | 0.0000 | 0.1581 | 0.8010 | 0.0000 | 0.2073 |

| Greenshoe Option | −2.5432 | 0.0070 | −0.7760 | −1.7885 | 0.0880 | −0.3564 | −2.1125 | 0.0420 | −0.5467 |

| IPO Waiting Period | 0.0002 | 0.5310 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.8260 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | 0.7680 | 0.0000 |

| Nasdaq Dummy | −0.1176 | 0.1800 | −0.0359 | −0.1116 | 0.2710 | −0.0222 | −0.1244 | 0.2010 | −0.0322 |

| Underwriter Rank | 0.0242 | 0.2990 | 0.0074 | 0.0075 | 0.7810 | 0.0015 | 0.0183 | 0.4730 | 0.0047 |

| Primary Shares | 0.1037 | 0.3320 | 0.0317 | −0.0331 | 0.7890 | −0.0066 | 0.0642 | 0.5860 | 0.0166 |

| Corporate Governance | |||||||||

| Board Size | 0.0182 | 0.3590 | 0.0055 | 0.0017 | 0.9410 | 0.0003 | 0.0207 | 0.3470 | 0.0054 |

| Female Ratio | −0.1985 | 0.5110 | −0.0606 | −0.3809 | 0.2730 | −0.0759 | −0.1104 | 0.7370 | −0.0286 |

| Succession Rate | −0.0125 | 0.9400 | −0.0038 | −0.2666 | 0.1650 | −0.0531 | −0.1915 | 0.3040 | −0.0496 |

| Network Size | −0.0209 | 0.3610 | −0.0064 | −0.0460 | 0.0760 | −0.0092 | −0.0296 | 0.2340 | −0.0077 |

| CEO Age | 0.0218 | 0.9160 | 0.0067 | −0.1472 | 0.5380 | −0.0293 | −0.0495 | 0.8270 | −0.0128 |

| CEO Duality | −0.0156 | 0.8460 | −0.0047 | 0.0253 | 0.7830 | 0.0050 | 0.0155 | 0.8610 | 0.0040 |

| Firm Characteristics | |||||||||

| Company Age | −0.0421 | 0.2440 | −0.0128 | −0.0241 | 0.5610 | −0.0048 | −0.0599 | 0.1340 | −0.0155 |

| Private Equity | 0.0186 | 0.8610 | 0.0057 | 0.0376 | 0.7610 | 0.0075 | 0.0694 | 0.5590 | 0.0180 |

| Auditor | −0.2024 | 0.0260 | −0.0618 | −0.1063 | 0.3230 | −0.0212 | −0.1613 | 0.1090 | −0.0417 |

| Venture Capital | 0.0629 | 0.4990 | 0.0192 | 0.1770 | 0.1040 | 0.0353 | 0.1225 | 0.2390 | 0.0317 |

| IT Dummy | −0.1766 | 0.0320 | −0.0539 | −0.2520 | 0.0110 | −0.0502 | −0.1341 | 0.1440 | −0.0347 |

| Firm Size | 0.0048 | 0.8430 | 0.0015 | −0.0030 | 0.9160 | −0.0006 | 0.0075 | 0.7790 | 0.0019 |

| Leverage | 0.0524 | 0.1160 | 0.0160 | 0.0386 | 0.3000 | 0.0077 | 0.0519 | 0.1400 | 0.0134 |

| Return on Assets | −0.0658 | 0.0690 | −0.0201 | −0.0534 | 0.1700 | −0.0106 | −0.0693 | 0.0780 | −0.0179 |

| Market Conditions | |||||||||

| Crisis | 0.0468 | 0.8130 | 0.0143 | 0.1424 | 0.5410 | 0.0284 | 0.1498 | 0.4840 | 0.0388 |

| VIX | −0.1576 | 0.2070 | −0.0481 | −0.2773 | 0.0580 | −0.0553 | −0.1682 | 0.2210 | −0.0435 |

| ΔInterest Rate | 0.3649 | 0.3300 | 0.1113 | −0.3966 | 0.4880 | −0.0790 | 0.1057 | 0.8430 | 0.0273 |

| ΔGDP | −1.1474 | 0.6200 | −0.3501 | 2.1197 | 0.4610 | 0.4224 | 0.2680 | 0.9140 | 0.0694 |

| ΔMarket Index | 0.1318 | 0.8930 | 0.0402 | 0.6044 | 0.6060 | 0.1204 | 0.9777 | 0.3710 | 0.2530 |

| Hotness Dummy | 0.0495 | 0.4820 | 0.0151 | 0.0311 | 0.7020 | 0.0062 | 0.0795 | 0.3090 | 0.0206 |

| Mc Fadden's Adj. R2 | 0.2720 | 0.2700 | 0.3210 | ||||||

| Hosmer–Lemeshow | 15.68 | 6.46 | 15.36 | ||||||

| N | 2111 | 1998 | 1992 | ||||||

- This table shows the results of two probit models. In Model 1, the dependent variable is a dummy variable that takes the value one if the IPO has a negative first-day return or a zero first-day return and zero otherwise. In Model 2, the dependent variable is a dummy variable that takes the value one if the IPO return lies within the 75th percentile of the negative first-day return sample, and zero otherwise. In Model 3, the dependent variable is a dummy variable that takes the value one if the IPO has a negative first-day return and zero if the IPO has a positive first-day return. The matched sample includes 2,111 observations in Model 1. Since the negative returns not included in the 75th percentile have been removed from the calculation, the sample size is reduced to 1,998 firms in Model 2. Since the zero first-day return IPOs (119) are removed from Model 3, the sample size is reduced to 1,992 firms. Robust standard errors are included in our analysis. Average Marginal Effects are defined as follows: the Probit employs normalisation that fixes the standard deviation of the error term to 1 where each coefficient represents the average marginal effect of a unit change on the probability that the dependent variable takes the value of either 0 or 1 given that all other independent variables are constant. The McFadden R-squared is defined as 1 less the log-likelihood for the estimated model divided by the log-likelihood for a model with only an intercept as the independent variable. While the Hosmer-Lemeshow Statistic represents the goodness of fit that observed events match estimated events in ten subgroups of the model population.

A similar pattern to our baseline results emerges as deal size and IPO price variables align significantly with H1. In Model 1, the probability of negative as well as zero first-day returns is decreased with a higher offer price (ME = −7.51%, p-value = 0.0480) and a higher amount of greenshoe options (ME = −77.60%, p-value = 0.0070). When prices are adjusted downwards in response to weaker pre-IPO market demand, the probability of overpricing increases. We find evidence for a certification function of the auditor (ME = −6.18%, p-value = 0.0260). Similar to the baseline results, we cannot identify a significant impact of agency issues and market conditions.

In Model 2, we find that while the offer price is no longer significant for the subsample of less overpriced IPOs, the price revision and stabilization variables show similar economic and statistical effects. With regard to corporate governance characteristics, one additional insight can be crystallized. Smaller network sizes significantly increase the probability of IPO overpricing. This is consistent with our conjecture, as firms with larger networks positively affect investor demand for IPO shares (Feng, Song and Tian, 2019), providing partial evidence in favour of H2. Additionally, we can find that the changes in the volatility index have an effect in terms of the overpricing phenomenon (ME = −5.53%, p-value = 0.0580), finding partial evidence for H4 and market timing arguments for moderately overpriced IPOs (Ibbotson, 1975).

When removing zero first-day returns in Model 3, the results do not change compared to Model 1 and our baseline. However, the offer price loses significance yet shows a similar sign.

Robustness section

Several robustness tests are executed to assess the adequacy of results. First, in Table A1, we examine a possible spillover effect of the general level of IPO overpricing in the market. We specify a market overpricing dummy that takes the value 1 if the frequency of the first-day performance for a given month is higher than the preceding 3-month moving average. We can identify a significant and positive effect of the market overpricing dummy on the probability of an IPO being overpriced, while other findings remain similar to our baseline model. This suggests that if there is a trend of overpricing in the market, it is more likely that subsequent IPOs will also be overpriced, possibly due to a prevailing cautious or negative investor sentiment.

Second, we employ a stepwise probit setting at a 5% significance level in Table A2. The results show similarity with our baseline framework in which deal size and greenshoe option significantly decrease the probability of IPO overpricing, while offer-to-first-open and being priced below the offer range significantly increase the same. Moreover, lower returns on assets show significance in increasing IPO overpricing, consistent with the idea that companies with low earnings potentials consider the appearance of having no prosperous and profitable prospects (Koop and Li, 2001).

Third, we consider whether some key variables could generate biased results. To this end, we employ other variations of the probit model with alternative measures of our independent variables. Specifically, we use interaction terms to explore specific effects in Table A3. In Model 1, we use an offer price interaction term, which consists of the offer price multiplied by an offer price dummy, which takes the value 1 if the offer price is below or equal to , and 0 otherwise. Offer prices below lead to an economical yet statistically insignificant increase in the probability of negative first-day returns. In Model 2, we add an interaction term concerning the deal size, which consists of the deal size multiplied by a deal size dummy that takes the value 1 if the deal size is below or equal to $500m, and 0 otherwise. Deal sizes below $500m accentuate the probability of negative first-day returns with the remaining results robust (ME = 0.28%, p-value = 0.0720). In Model 3, we also create an interaction term consisting of the IPO waiting period multiplied by an IPO waiting period dummy that takes the value 1 if it is more than 270 days between the announcement of the IPO and the trading on an exchange, and 0 otherwise. We chose this in line with Zhang (2012), as typically, after 270 days, an offer could be deemed withdrawn from the SEC (Busaba, 2006). We cannot identify the significance of a longer IPO waiting period (270 days) on the probability of negative first-day returns (ME = 0.0000%, p-value = 0.8890).

Fourth, in Table A4, we use the 5-day performance after the IPO as an alternative measure to the first-day returns. We now classify IPOs as overpriced if they exhibit negative returns on day 5 after the IPO (1031, average −7.83%), thereby capturing a longer performance horizon than the first day of trading. We can observe results similar to those of our baseline model. The pre-IPO downward price adjustments, IPO waiting period and offer price significantly increase the probability of negative 5-day returns, whereas now the greenshoe option loses its significance but still harms IPO overpricing. Consistent with previous literature on IPO performance (Koop and Li, 2001; Lowry, Officer and Schwert, 2010; Signori, 2018), we can identify a size effect whereby a larger firm size and better financials decrease the probability of negative 5-day returns.

Addressing endogeneity concerns, we validated our results by employing a two-stage least squares (2SLS) estimation method as advised by Lowry and Murphy (2007) and Busaba and Restrepo (2022). Detailed results of this robustness check are available in the Online Appendix (Tables A.5 and A.6). Table A.7 illustrates that major US legislative changes do not impact the occurrence or determinants of IPO overpricing.

The robustness tests corroborate our findings, revealing that smaller deal sizes and return on assets increase the likelihood of IPO overpricing, while larger firm sizes and stronger financials decrease the probability of negative returns.

Conclusion

This research addresses IPO overpricing and determinants of negative first-day IPO returns, a previously untouched topic in the IPO discourse. Drawing from theoretical underpricing literature, we examine overpricing by analysing 2111 US IPOs between 2000 and 2020. Utilizing univariate, linear and probability analyses, we illuminate the significance of IPO overpricing, demonstrating that pre-IPO market demand is a driving factor. We can conclude that IPO overpricing cannot be simply inferred as the opposite of IPO underpricing, as our results show. The study indicates that downward adjustments of the offer price or an opening price lower than the offer can significantly increase the likelihood of negative first-day returns, thereby serving as markers for IPO overpricing. A greenshoe option, representing aftermarket demand flexibility, significantly reduces IPO overpricing probability. Other findings highlight the critical role of information asymmetries: the decreased likelihood of negative first-day IPO returns with larger deal sizes or technology IPOs and the increased overpricing probability with weaker financials. We find inconclusive evidence on market timing or agency issues and limited support for certification effects such as VC or PE.

In this paper, we extend the evidence and ideas on IPO underpricing to the phenomenon of IPO overpricing. We can conclude that common characteristics determine IPO underpricing and overpricing (IPO size, offer price revisions, technology sector). At the same time, there are pronounced differences between these two phenomena. First, weak pre-market demand (price adjustments) translates into higher overpricing. Second, stabilization mechanisms (greenshoe option) are essential to avoid overpricing. Third, we cannot identify significant determinants of market characteristics or agency issues. This leads us to conclude that a ‘hot’ market phenomenon cannot be applied to IPO overpricing. Companies attempting to ride the wave may experience significant underpricing, but ‘hot’ markets do not seem to decrease IPO overpricing. Characteristics of information provision and IPO mechanism are the primary drivers of IPO overpricing.

Despite focusing on US IPOs, our findings have far-reaching implications for international capital markets. They explain how a global market's distinctive attributes could influence IPO pricing dynamics. In similar frontier markets between 2000 and 2020, the IPO overpricing phenomenon is evident (see Table A.8 in the Online Appendix). IPO overpricing is more pronounced in other common law and European markets, except the United Kingdom, which might be due to the second-tier stock market. In contrast, Asian markets show fewer overpriced IPOs. Our research warrants further exploration of global financial markets, emphasizing the need for improved transparency.

The managerial implications of our research are particularly noteworthy. The potential risks associated with overpriced IPOs make understanding this phenomenon essential for investors, IPO firms and financial intermediaries. Enhanced knowledge about overpricing can guide managerial decisions in the IPO process.

Admittedly, our study has limitations. We acknowledge that IPO phenomena in a globalized world are too complex to be generalized by single-country studies. Given IPO overpricing in frontier markets, future studies can contribute to this debate by examining cross-country and institutional factors. Our analysis might also suffer from unobserved heterogeneity of characteristics and findings. We are confident, however, that we have captured IPO overpricing in the United States in depth and breadth. Further research must examine the aftermath of overpriced IPOs on post-IPO performance, corporate governance and long-term value creation. Delving into the strategic financial decisions made by firms post-IPO, particularly how the excess capital raised from overpriced IPOs is allocated, could provide insights into how initial overvaluation is mitigated or exacerbated by post-IPO financial management. We find a material number of IPOs with zero first-trading-day returns. By isolating these IPOs in future analyses, researchers could uncover nuanced insights into how and why these IPOs perform as they do. While traditional finance theories offer substantial insights into the complexities of IPO pricing, recent scholarly discourse suggests the potential applicability of alternative explanations, particularly how behavioural aspects might affect pricing decisions as well as IPO allocation theories. Exploring this parallel could unveil further intricacies in IPO pricing strategies and investor behaviour.

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by IReL.

Biographies

Jacqueline Rossovski is an Adjunct Assistant Professor at the Edinburgh Business School, Heriot-Watt University. She holds an MSc and PhD in Finance from Trinity College Dublin. Her main area of research interest is in corporate finance.

Brian Lucey is a Professor of International Finance and Commodities at the Trinity Business School in Dublin. His main research interests are corporate, international and commodity finance.

Pia Helbing is an Associate Professor in Finance at the University of Glasgow. She holds an MSc and PhD in Finance from Trinity College Dublin. Her work on initial public offerings, venture capital and private equity has been published or is forthcoming in journals, including the British Journal of Management, Journal of Corporate Finance and International Review of Financial Analysis, among others.

References

- 1 In the United States, there is a quiet period that significantly limits the ability of analysts to produce research coverage about IPO firms (Jia et al., 2018).

- 2 Since much IPO data is incomplete, we added data provider S&P Capital IQ to cross-check our existing data and increase our sample size. All data were manually rechecked, cleaned and supplemented based on the respective IPO prospectuses.

- 3 Zero first-day returns signify accurate pricing at the time of the IPO, serving as a benchmark for evaluating the determinants of IPO overpricing.

- 4 We count the absolute zero first-day returns as positive first-day returns for the baseline analyses.