Do Climate Change Regulatory Pressures Increase Corporate Environmental Sustainability Performance? The Moderating Roles of Foreign Market Exposure and Industry Carbon Intensity

Abstract

This study focuses on climate change regulatory pressures at the national/regional level, which can be considered emergent institutions – newly established and subject to change – in contrast to established institutions. We explore their impact on the environmental sustainability performance of multinational enterprises, advancing beyond the extant literature's focus on their binary compliance reactions. Utilizing a sample of Standard & Poor's 1200 firms, our findings indicate that variations in climate change regulatory pressures at the national/regional level can account for differences in environmental sustainability performance at the corporate level. Moreover, this relationship is moderated by two critical firm characteristics: foreign market exposure and industry carbon intensity. Foreign market exposure, particularly in the context of developing countries, can diminish the positive effects of a home country's climate change regulatory pressures, while industry carbon intensity can amplify these effects.

Introduction

It has taken over three decades to achieve scientific consensus on anthropogenetic climate change (Cook et al., 2016; Oreskes, 2004). This often makes it inevitable that climate change policies, regulations and laws are associated with controversy and are difficult to establish in certain countries. That is, it takes time and effort for governments to consolidate the regulatory environment required to combat climate change. For instance, via its Federal Act on Climate Protection Goals, Innovation and Strengthening of Energy Security, Switzerland is, thus far, the only country to include a legal requirement for companies to shift to net zero (Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, 2023). The clarity and uniformity of climate change laws and regulations remain elusive worldwide, marked by significant variations in regulatory pressures across time and regions. Additionally, the green backlash is increasingly frequent in some developed countries owing to rising levels of political polarization and populism. In light of the significant variations and increasing deterioration across the globe, it is imperative to initiate a cross-country analysis of climate change regulatory pressures to better understand their roles in helping the private sector improve environmental sustainability performance (ESP) and transition to net zero.

The research on management and broad environmental regulatory pressures has concluded that firms are more responsive to regulatory stakeholder pressures than to other stakeholder groups. In a related review study, Aragòn-Correa, Marcus and Vogel (2020) summarize broad environmental regulatory pressures, especially in the United States, and document their effect on strategic reactions. For instance, Darnall, Henriques and Sadorsky (2010) find that companies respond to heightened environmental regulatory pressures by engaging more substantially in proactive environmental practices. Given that environmental concerns have been growing since the 1960s, when Rachel Carson's Silent Spring was published, broad environmental regulatory pressures tend to be stable over time.

However, climate change, as a ‘super wicked’ environmental challenge, and its regulatory pressures are more volatile (George et al., 2016). Still, the existing literature ignores the distinctiveness of climate change regulatory pressures, namely that they were established in a relatively short time period (Gupta, 2010) and, more importantly, are highly susceptible to changes (Dutt and Joseph, 2019). For instance, the Trump administration's decision to withdraw the United States from the Paris Agreement in 2017 represented a significant change in climate change regulatory pressures. It also signalled a change in the regulatory environment, as the commitment to the Paris Agreement under the Obama administration had led to the development of numerous climate and energy policies intended to meet the emissions reduction target (Jotzo, Depledge and Winkler, 2018). This underscores the need for further research to unravel the intricate dynamics and implications of climate change regulatory pressures.

With a few exceptions, Cadez et al. (2019) specifically focus on climate change regulatory pressures and confirm their effect on the implementation of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reduction strategies. Despite this, ‘the literature often treats enforcement of mandatory regulation as simple binary (i.e. does a firm comply or not to comply)’, and the latitude for compliance remains insufficiently clear (Aragòn-Correa, Marcus and Vogel, 2020, p. 345). Accordingly, a guiding research question for this paper is as follows: How do climate change regulatory pressures at the national/regional level affect ESP at the corporate level?

To address this question, we build upon the theoretical perspective around emergent institutions that challenges conventional institutional theory's assumption that institutions are stable over time (Henisz and Zelner, 2005; North, 2005). Regarding climate change, there is an apparent lack of widespread recognition and significant variation in political systems across institutional contexts (i.e. countries/regions), resulting in a vulnerable regulatory environment concerning climate change. We argue that despite their instability, climate change regulatory pressures are crucial in prompting firms to enhance their ESP. This goes beyond meeting minimum regulatory requirements in combating climate change. It also includes efforts to address other environmental challenges that may not be directly caused by the companies themselves (Klassen and McLaughlin, 1996; Thornton, Kagan and Gunningham, 2003).

Furthermore, we contend that stopping at this point would leave the picture incomplete, as it neglects to consider the firm-level contingencies. As noted by Aragòn-Correa, Marcus and Vogel (2020), there is a great need to understand the role of firm-level contingent factors in responding to regulatory pressures. Therefore, we propose the second research question: How are the internal factors affecting the relationship between climate change regulatory pressures at the national/regional level and ESP at the corporate level? For multinational enterprises (MNEs), one of the crucial factors is related to their operations that transcend discrete geographical boundaries. That is, the response of MNEs to home-country climate change regulatory pressures can be contingent on their foreign market exposure, especially their exposure to developing countries characterized by weak regulatory environments (Bueno-García et al., 2022). Meanwhile, the primary operating industry of those MNEs represents another crucial factor that has been under-analysed (Aragòn-Correa, Marcus and Vogel, 2020). This is significant because the sensitivity to regulatory pressures varies among industries (Fu, Tang and Chen, 2020). Specifically, MNEs in carbon-intensive industries are more likely to be sensitive to regulatory pressures, thereby making them more motivated to enhance their ESP (Guenther et al., 2016; Hahn, Reimsbach and Schiemann, 2015).

Empirically, we draw on a sample of Standard & Poor's (S&P) 1200 firms and obtain national/regional- and firm-level data from multiple sources. The empirical results confirm our theoretical predictions. To address the endogeneity concerns that commonly exist in cross-country research (Reeb, Sakakibara and Mahmood, 2012), we take advantage of Donald Trump's unexpected rise to presidential power and conduct a difference-in-differences analysis. The analysis bolsters the causal inference of the proposed baseline relationship between national- and regional-level climate change regulatory pressures and MNE-level ESP. This design also addresses the calls for global strategy research using rare events (Beamish and Hasse, 2022).

This research makes two important contributions. First, we are not aware of any work that directly examines the effect of climate change regulatory pressures on MNEs in a cross-country setting. Despite the growing body of research investigating the various impacts of climate change events (Javadi and Masum, 2021), risks (Huang, Kerstein and Wang, 2018) and policies (Clark and Crawford, 2012) on business, our comprehension of how climate change regulatory pressures at the national/regional level influence ESP at the corporate level is still inadequate, and a multi-country analysis on this matter is still lacking. Our findings provide strong empirical evidence of a positive spillover, such that MNEs headquartered in countries/regions with more stringent climate change regulatory pressures tend to proactively address environmental concerns, notably enhancing corporate ESP. Few studies have investigated the interplay between national/regional factors about climate change and MNE characteristics. Therefore, incorporating foreign market exposure and industry carbon intensity as moderators in the relationship between climate change regulatory pressures and corporate ESP is another of this study's contributions. We find that the significant and positive impact of climate change regulatory pressures on corporate ESP is contingent not only on the extent to which an MNE relies on foreign developing markets with relatively weak institutions (i.e. foreign market exposure) but also on stakeholder pressure for ‘good deeds’ (e.g. industry carbon intensity). More specifically, an MNE's foreign market exposure attenuates the necessity and urgency of responding to climate change regulatory pressures from their home country by improving ESP. Meanwhile, industry carbon intensity strengthens the impact of climate change regulatory pressures and corporate ESP.

Second, our paper contributes to institutional theory by empirically examining institutions of climate change, which we regard as emergent institutions. According to Henisz and Zelner (2005), emergent institutions can be defined as newly formed or developing institutions that are not yet fully established. The effectiveness, appropriateness, and fairness of climate change regulations remain under considerable scrutiny, as is evidenced by ongoing debates in media, politics, academia, and society at large (Page, 2007). This ongoing evaluation aligns with the notion of emergent institutions, which are subject to evaluation, unlike established institutions whose outcomes are beyond normative assessment owing to their ‘taken-for-grantedness’ (Henisz and Zelner, 2005). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first empirical study to investigate the emergent institutions of climate change – as formal institutions but with some distinctive features. The cross-country panel data also allows us to capture the changes in climate change regulatory pressures across time. Furthermore, we contend that the responses of MNEs to emergent institutions are not time-enduring – ESP can be compromised quickly when firms feel a sense of change. This also contrasts with the conventional view that formal institutions are stable by drawing attention to short-term institutional change (Mickiewicz, Stephan and Shami, 2021).

Theoretical background and hypothesis development

Climate change regulatory pressures: An emergent institution perspective

Institutional theory posits that organizations adopt managerial practices and actions to conform to the expectations of institutions and enhance or protect their legitimacy (DiMaggio and Powell, 1983; Oliver, 1991; Scott, 1995). National institutions are considered one of the most influential factors driving variation in the performance of global companies (Fainshmidt et al., 2018). Notably, the diversity of national institutional profiles decides the MNE-level strategic practices of MNEs in both home and host countries. Hence, cross-country differences are of great importance for exploring the heterogeneity of MNEs’ foreign investments (Bu, Luo and Zhang, 2022), innovation commitment (Li et al., 2022), and corporate social responsibility initiatives (Ghoul, Guedhami and Kim, 2017).

Importantly, the existing literature mostly examines these institutions through the lens of established institutions, that is, institutions that have widespread and implicit acceptance (Zucker, 1987). According to the taxonomy of Crossland and Hambrick (2011), institutions can generally be classified as formal (characterized by, for example, common-law legal origins and economic freedom) or informal (characterized by, for example, individualism and power distance). These institutional factors have achieved a level of cognitive legitimacy (Henisz and Zelner, 2005), meaning that these established institutional factors have also generally been accepted as the ‘norm’ or ‘standard’ within societies (Henisz and Zelner, 2005), and they typically operate without active or regular contention or dispute. However, an exclusive focus on established institutions potentially overlooks the dynamic and rapidly evolving aspects of our societal, economic, and political landscapes. The current era, characterized by unprecedented global challenges such as climate change, can be understood as being marked by the increasing relevance of emergent institutions, namely new formal structures that remain subject to scrutiny and evaluation.

Climate change regulatory pressures mainly include laws, regulations, and policies on combating climate change at the national/regional level. Additionally, some international agreements (e.g. the Paris Agreement), which are signed by some countries, are also considered an integral aspect of regulatory institutions. Although labelled formal institutions, climate change regulatory pressures have their distinctions. Specifically, climate change regulatory pressures can be considered ‘emergent institutions’, because, despite achieving a certain level of structure, formality and legitimacy, they are newly established and ‘still subject to evaluation’ (Henisz and Zelner, 2005, p. 363). Climate change has often been the subject of political debate, resulting in the instability of regulatory pressures in some institutional settings (Cann and Raymond, 2018). This offers us an opportunity to explore the dynamic changes in climate change regulatory pressures as emergent institutions (Henisz and Zelner, 2005; Kolk and Pinkse, 2008; Pinkse and Kolk, 2012).

As noted by Aragòn-Correa, Marcus and Vogel (2020, p. 350), ‘although many mandatory programmes have been analysed, the analyses almost always are performed in isolation’. These regulatory programmes include the UK's mandatory carbon reporting scheme (Bauckloh et al., 2023), carbon tax, and carbon trading (Jia and Lin, 2020). However, we lack a comprehensive understanding of the climate change regulatory pressures at the national/regional level and their impact on MNEs' ‘latitude in how to comply’ instead of a binary strategic reaction (i.e. compliance/adherence or not) (Aragòn-Correa, Marcus and Vogel, 2020, p. 347).

Climate change regulatory pressures and corporate ESP

Climate change regulatory pressures encapsulate a broad spectrum of climate change laws, regulations, and policies at the national/regional level. To mitigate the intensification of these pressures, corporate actors strive to bolster their ESP. However, this is not merely an exercise in legal compliance or risk avoidance. Rather, it signifies a strategic decision to cultivate competitive advantage. Firms that enhance their ESP in response to regulatory pressures are also likely to reap economic benefits by better positioning themselves in the market. Hence, the bid to improve ESP serves a dual purpose: adhering to regulatory requirements while simultaneously advancing the strategic goals of MNEs to obtain competitive advantages.

Climate change regulatory policies – a key component of regulatory pressures – differ in their primary aim of mitigating long-term, global-scale environmental impacts (Bowen, Bansal and Slawinski, 2018). Climate change regulatory policies often encompass measures such as carbon pricing, energy efficiency mandates, and renewable energy incentives (Jia and Lin, 2020). These policies fundamentally differ from pollutant-specific reduction policies, which typically target immediate, local, and regional environmental health hazards posed by specific pollutants, such as SO2. While it is true that climate change often intersects with other environmental issues, such as air quality, biodiversity, and water scarcity (Araújo and Rahbek, 2006; Jacob and Winner, 2009; Ma et al., 2011), our argument maintains that firms’ responses to heightened climate change regulatory pressures will be more strategic, extending beyond mere emissions reduction. In other words, corporate ESP, reflecting decreased impacts on the natural environment, can be enhanced.

However, it is essential to acknowledge potential conflicts with other environmental goals. In situations where compliance with climate change regulations might inadvertently increase other kinds of pollution, firms face a complex challenge (Ringquist, 2011). For instance, although switching to biofuels would reduce GHG emissions, it could lead to deforestation or increase water pollution owing to fertilizer runoff (Cherubini et al., 2009). In such scenarios, firms are required to strike a balance between different environmental objectives, which in turn requires innovative problem-solving and comprehensive sustainability strategies. In essence, these climate-specific regulations push firms to adopt broader and more innovative strategies, rather than having a narrow focus on complying with specific pollutant regulations. This means that firms must engage in continuous learning and adaptation, as well as embracing more systemic and sustainable changes to their business models and operations (i.e. enhanced corporate ESP).

From a legitimacy perspective, regulatory compliance is an essential requirement for firms to gain social approval and support from various stakeholders, including the government, investors, customers, and the general public (Kostova, Roth and Dacin, 2008; Wang et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2023). Previous studies have identified regulatory institutions as a driving factor of firms’ environmental sustainability commitment and engagement. For instance, Roxas and Coetzer (2012) report that managers perceived regulatory institutions to have a positive effect on firms’ environmental orientations. In a similar vein, Rowe and Guthrie (2010) document how managers’ perceptions of regulatory institutions are the most influential factor in facilitating corporate environmental management and reporting in China.

In terms of climate change regulatory pressures, we argue that when governments adopt, enact, and enforce stringent climate change laws and regulations or ratify international climate agreements, firms in these countries will seek to navigate these pressures by aligning their operations and strategies to meet or exceed these emerging demands. The process driving this reaction can be conceptualized through the lens of institutional theory. Managers perceive the risk associated with increased climate change regulatory pressures – notably, potential legal penalties for non-compliance and reputational harm – and consequently prioritize actions that ensure adherence to these climate standards to avoid these foreseeable risks.

Despite the emergent nature of the institution of climate change regulatory pressures, it is pertinent to note that they are likely to consolidate over time and become institutionalized norms within society (Henisz and Zelner, 2005). From the perspective of economic motives, firms are not mere passive observers in this process. Rather, they anticipate this transition and adjust their practices accordingly, aiming to be frontrunners rather than followers. Therefore, this forward-looking stance on emerging institutional pressures is not just about risk mitigation but also serves a strategic purpose. For instance, by proactively investing in renewable energy technologies, firms can reduce their dependence on fossil fuels not only to align with the growing climate change regulatory pressures but also to ensure a stable and potentially less costly energy supply in the future.

Taking these arguments together, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1.(H1): Climate change regulatory pressures at the national/regional level have a positive relationship with ESP at the corporate level.

The moderating role of firm characteristics

The previous section's discussion demonstrates the external determinant of climate change regulatory pressures at the national/regional level. Legal compliance with these institutions helps firms establish, maintain, or repair their environmental legitimacy (Berrone, Fosfuri and Gelabert, 2017; Suchman, 1995). However, overlooking firm-level contingent characteristics leads to a less-than-comprehensive picture of the baseline relationship proposed in H1 (Aragòn-Correa, Marcus and Vogel, 2020). Hence, for MNEs, we argue that the positive relationship between climate change regulatory pressures and corporate ESP also depends upon two critical internal contingencies: industry carbon intensity and foreign market exposure.

We propose that an MNE's primary operating industry significantly influences its responses to climate change regulatory pressures, particularly for highly carbon-intensive industries. Owing to their substantial contribution to GHG emissions, MNEs in these industries often find themselves under intensified regulatory and societal scrutiny (Cho and Patten, 2007; Guenther et al., 2016; Hahn, Reimsbach and Schiemann, 2015). For instance, Shui, Zhang and Smart (2023) claim that carbon transparency is expected for MNEs with greater amounts of emissions. These environmental pressures parallel the social pressures experienced by MNEs operating in culpable industries, prompting greater allocation of attention to the social domain, as documented by Fu, Tang and Chen (2020). Similarly, MNE stakeholders (including investors, regulators, and the broader public) in carbon-intensive industries tend to be highly concerned about their environmental footprint, often because MNEs in these industries are frequently the target of negative media coverage, heightening sensitivity towards their environmental image (Hahn, Reimsbach and Schiemann, 2015).

Hence, promoting corporate ESP can also be a crucial point of differentiation in carbon-intensive industries, where the environmental stakes and regulatory pressures are heightened. MNEs in these industries not only align better with climate change regulatory pressures through robust environmental practices but also differentiate themselves from less proactive competitors. In other words, the legitimacy motive serves not only to protect the MNE from the negative repercussions of environmental irresponsibility but also to potentially enhance its competitive positioning through proactive environmental practices. This differentiation can confer competitive advantages, such as preferential treatment from stakeholders, a stronger brand image, and potential cost savings from efficient resource use (Hart and Dowell, 2011), amplifying the effect of regulatory pressures on corporate ESP. Thus, in an environment featuring intense legitimacy pressures, such as carbon-intensive industries, proactive environmental practices in response to climate change regulatory pressures can yield both societal acceptance and a competitive edge.

While the legitimacy motive is potent in carbon-intensive industries, its influence may not be as substantial in non-carbon-intensive industries. According to Hahn, Reimsbach and Schiemann (2015), MNEs in non-carbon-intensive industries are less threatened by legitimacy issues (e.g. litigation risks or environmental-activist groups). Therefore, we argue that these MNEs may experience less immediate benefit from significantly investing in environmental sustainability to respond to climate change regulatory pressures as a means of differentiating themselves within their industry. However, it is important to note that this does not absolve MNEs in non-carbon-intensive industries of their responsibility to the environment. Instead, it merely highlights the varying degrees of climate change regulatory pressures and related societal expectations they encounter, which, in turn, shape their responses to those pressures. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2.(H2): Industry carbon intensity strengthens the relationship between climate change regulatory pressures at the national/regional level and ESP at the corporate level.

In addition, MNEs with extensive foreign market exposure operate in various economic and institutional landscapes (Schmid and Roedder, 2021). This institutional multiplicity (e.g. diversity of regulatory environments) offers MNEs an opportunity to engage in institutional arbitrage (Bu, Xu and Tang, 2023; Sun et al., 2021), which means adjusting their operations across different regions to optimize economic outcomes. MNEs with substantial foreign market exposure can be flexible in navigating various institutional contexts. This potentially moderates the positive relationship between climate change regulatory pressures and corporate ESP, an effect we attribute to institutional arbitrage. Surroca, Tribó and Zahra (2013) detail how MNEs might respond to increasing domestic corporate social responsibility demands by engaging in institutional arbitrage and transferring corporate socially irresponsible activities to their foreign subsidiaries in countries with less rigorous legitimacy requirements. This approach capitalizes on the cost advantages provided by the institutional frameworks of those host countries.

Consistent with this, the environmental management strategies of MNEs that demonstrate heightened environmental concerns often reveal a propensity for investing in regions with weaker environmental regulations (Bu and Wagner, 2016). This finding aligns with the Pollution Haven Hypothesis, which postulates that MNEs may offload their environmental externalities by offshoring their production to countries with weaker environmental regulations (Li and Zhou, 2017; Zhang et al., 2020). This might involve an MNE with substantial foreign market exposure strategically relocating their environmentally detrimental practices to other countries, thereby securing economic benefits and mitigating the effects of domestic climate change regulatory pressures. For instance, companies headquartered in the United States, which features relatively stringent emission standards, have been reported to shift part of their manufacturing process to countries where the environmental standards are less strict. This move is primarily driven by cost-saving motives, suggesting that foreign market exposure might indeed dilute the influence of domestic climate change regulatory pressures on the MNE's overall ESP.

In addition, previous studies have suggested that MNEs have more bargaining power to affect the establishment of climate change regulatory pressures (Kolk and Pinkse, 2008). They often use lobbying to pressure firms not to adopt internationally recognized frameworks, such as the Kyoto Protocol, and some domestic environmental regulations, such as carbon trading schemes (Kolk and Pinkse, 2007). Prominent examples include the behaviour of MNEs in the energy sector (e.g. ExxonMobil) during the early stages, when immense uncertainties surrounded climate change (Supran and Oreskes, 2017). Building on this discussion, we propose our third hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3.(H3): Firms’ foreign market exposure weakens the relationship between climate change regulatory pressures at the national/regional level and ESP at the corporate level.

Research methods

Sample and data

To test the hypothesized relationships from a global perspective, we started by compiling a dataset based on a sample of S&P 1200 firms from 2007 to 2019, representing 33 countries/regions across the globe and 67 industries at the level of the six-digit Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS) code. We sourced the data from diverse sources, including Germanwatch e. V., Bloomberg, BvD Orbis, Datastream, Thomson Reuters ASSET4 (now Refinitiv), and the World Bank. Table 1 describes the composition of the observations by countries/regions and the mean corporate ESP after merging different data sources. Table 2 then presents detailed explanations of the source of variables.

| ESP – descriptive statistics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observations | Proportion (%) | M | SD | Median | |

| Australia | 423 | 4.34 | 57.500 | 22.119 | 57.129 |

| Austria | 35 | 0.36 | 67.950 | 10.907 | 66.679 |

| Belgium | 104 | 1.07 | 60.667 | 26.381 | 63.276 |

| Brazil | 47 | 0.48 | 58.664 | 21.002 | 60.296 |

| Canada | 494 | 5.06 | 58.994 | 26.557 | 66.947 |

| China | 55 | 0.56 | 36.638 | 19.987 | 33.641 |

| Denmark | 121 | 1.24 | 61.256 | 18.993 | 63.181 |

| Finland | 119 | 1.22 | 73.769 | 15.193 | 78.075 |

| France | 490 | 5.02 | 76.721 | 16.786 | 81.479 |

| Germany | 191 | 1.96 | 73.793 | 18.921 | 79.088 |

| Ireland | 140 | 1.44 | 48.705 | 24.735 | 49.127 |

| Italy | 167 | 1.71 | 73.003 | 22.073 | 80.130 |

| Japan | 1322 | 13.55 | 63.261 | 22.376 | 69.228 |

| Luxembourg | 36 | 0.37 | 60.265 | 23.940 | 65.558 |

| Mexico | 49 | 0.50 | 61.823 | 25.200 | 72.830 |

| Netherlands | 145 | 1.49 | 67.783 | 18.239 | 70.224 |

| Norway | 63 | 0.65 | 70.555 | 15.791 | 76.490 |

| Portugal | 23 | 0.24 | 78.422 | 7.412 | 80.246 |

| Singapore | 44 | 0.45 | 36.971 | 22.302 | 23.525 |

| South Korea | 119 | 1.22 | 67.816 | 21.136 | 72.062 |

| Spain | 183 | 1.88 | 80.031 | 12.623 | 84.130 |

| Sweden | 191 | 1.96 | 71.681 | 19.914 | 76.916 |

| Switzerland | 222 | 2.28 | 73.272 | 20.851 | 77.423 |

| the United Kingdom | 961 | 9.85 | 63.979 | 21.498 | 68.177 |

| the United States | 4011 | 41.12 | 49.697 | 27.763 | 53.801 |

| Total | 9755 | 100.00 | 58.825 | 26.036 | 64.220 |

| Variable | Definition | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental sustainability performance | The environmental pillar score measures a firm's achievements in minimizing their negative impacts on the natural environment. Higher scores suggest better environmental performance. | ASSET4 (now Refinitiv) |

| Climate change regulatory pressures | The climate policy score reflects governmental regulatory efforts in implementing relevant policies aiming to tackle global warming and climate change. | Germanwatch |

| Industry carbon intensity | In line with Carbon Disclosure Project's definition, oil and gas (GICS: 101020), chemicals (GICS: 151010), construction materials (GICS: 151020), metals and mining (GICS: 151040), papers and forest products (GICS:151050), electric utilities (GICS: 551010), gas utilities (GICS: 551020), multi-utilities (GICS:551030), and independent power (GICS:551050) are considered as carbon-intensive industry. This is measured as 1 if firms primarily operate in these industries and 0 otherwise. | Bloomberg |

| Foreign market exposure | The ratio of the number of subsidiaries in developing countries based on the IMF's definition to the total number of foreign subsidiaries (i.e. subsidiaries located in countries different from the country of the headquarters). | BvD Orbis |

| Financial leverage | The ratio of average assets to average equity. | Bloomberg |

| Price-to-book ratio | Market capitalization over book value. | Bloomberg |

| Return on equity | The ratio of pre-tax profits to equity. | Datastream |

| Firm size | The natural logarithm of total assets. | Bloomberg |

| Links with green NGOs | This is a dummy variable that equals 1 if firms have partnerships with environmental NGOs and 0 otherwise. | ASSET4 (now Refinitiv) |

| Environmental management system | This is a dummy variable that equals 1 if firms have adopted ISO14000 or other relevant environmental management systems and 0 otherwise. | ASSET4 (now Refinitiv) |

| Board sustainability committee | This is a dummy variable that equals 1 if firms have a sustainability (or equivalent) committee that reports directly to the board and 0 otherwise. | Bloomberg |

| Board independence | The number of independent directors to the total number of directors in the boardroom. | Bloomberg |

| Executives ESG-related compensation | This is a dummy variable that equals 1 if executive compensation is linked to ESG goals and 0 otherwise. | Bloomberg |

| Female CEO | This is a dummy variable that equals 1 if the CEO or equivalent is female and 0 otherwise. | Bloomberg |

| GDP per capita | This is the national/regional GDP divided by the total population. | The World Bank |

| Political stability | This measures the perceptions of the likelihood of political instability and/or politically motivated violence, including terrorism. | The World Bank |

Measurement

Outcome variable

We use the environmental pillar score from Thomson Reuters ASSET4 (now Refinitiv) to measure ESP. The data vendor utilizes multiple sources to assess the firm's performance in minimizing its impacts on the natural environment via multiple sources from three dimensions – (1) emissions reduction, (2) resource usage, and (3) environmental innovation (Cheng, Ioannou and Serafeim, 2014). It effectively gauges a company's ESP, intricately aligning it with the multidimensionality proposed by theorists of environmental sustainability management (Hart, 1995; Hsu, Liang and Matos, 2023; Semenova and Hassel, 2015). The score ranges from 0 to 100, with higher values denoting better ESP.

Explanatory and moderating variables

We use Climate Policy, one of four indicators included in the Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI) (https://ccpi.org/) published by Germanwatch e.V since 2007. The CCPI endeavours to improve transparency in climate protection efforts across countries, and it has been utilized in many academic studies (e.g. Guenther et al., 2016; Huang, Kerstein and Wang, 2018). We believe that this indicator is appropriate for three reasons. First, the approach is consistent with precedents of leveraging the index to proxy institutional pressures (e.g. Aresu, Hooghiemstra and Melis, 2023). Second, the indicator measures aggregated national/regional-level climate change regulatory pressures, as it considers not only the country's domestic engagement but also its international engagement in advancing climate change policies, laws, regulations, and multilateral agreements (CCPI, 2022). Third, the score not only accounts for the comprehensiveness of climate change laws, policies, and regulations but also factors in their enforcement stringency. This makes it a consistent measure that aligns with theorizations of the variable as outlined in Aragòn-Correa, Marcus and Vogel (2020). This measure ranges from 0 to 20, with higher values representing more stringent climate change regulatory pressures.

Industry carbon intensity is measured as a dummy variable that equals 1 if MNEs primarily operate in carbon-intensive industries according to the Carbon Disclosure Project's definition and 0 otherwise. Additionally, to capture foreign market exposure, especially exposure in developing contexts, we use the ratio between the number of subsidiaries in the developing countries based on the IMF's definition and the total number of foreign subsidiaries (i.e. subsidiaries located in countries other than the country of the MNE's headquarters). The data for this variable are obtained from BvD Orbis.

Control variables

At the firm level, several internal characteristics are suggested to affect ESP in the extant scholarship. Financial leverage, indicating financial slack, can affect firms’ efforts in enhancing ESP (Modi and Cantor, 2021). This is measured as the ratio of average assets to average equity and is controlled for in the empirical analysis. Price-to-book ratio, measured as the ratio of market capitalization to book value, can affect firms’ efforts to improve their ESP (Yan, Almandoz and Ferraro, 2021). Considering that profitable firms are argued to engage in more socially responsible activities, return on equity, measured as the ratio of pre-tax profits to equity, is accounted for. Larger firms are more likely to be pressured to engage in socially responsible activities, so firm size, measured as the natural logarithm of total assets, is controlled for. Firms’ links with green nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), measured as a dummy variable, is controlled for because these links can significantly cause MNEs to be environmentally responsible. Firms’ adoption of the environmental management system (e.g. ISO 14000) – again using a dummy measure – is a driving factor of improvement in ESP, and we control for it in the study.

We also control for the board sustainability committee, using a dummy measure to denote the presence of such a committee, because it is positively associated with the ESP of MNEs (Fu, Tang and Chen, 2020). Board independence, measured as the ratio between the number of independent directors and the total number of directors in the boardroom, is also argued to facilitate firms to be environmentally responsible and therefore is included in the analysis (Walls, Berrone and Phan, 2012). Given that firms are starting to implement an executives’ ESG-related compensation policy to align management with sustainability goals, we control for it using a dummy variable (Aresu, Hooghiemstra and Melis, 2023; Haque and Ntim, 2020). Recognizing that some studies argue that MNEs led by female CEOs are more likely to be socially responsible (Liu, 2021), this is included in the analysis by taking the variable as equal to 1 if the MNE is led by a female CEO and 0 otherwise.

At the national/regional level, we control for GDP per capita, obtained from the World Bank, because MNEs in countries/regions with higher GDP per capita can allocate more resources to environmental sustainability (Li and Lu, 2020). Additionally, we control for other dimensions of national-level established institutions, especially political stability, which has been found to influence corporate environmental commitment (Hsu, Liang and Matos, 2023). Table 2 provides the definitions and sources of all variables used in this study.

Estimation methods

To estimate the effect of climate change regulatory pressures on corporate ESP, we apply a panel linear regression with year and country fixed effects. This approach can help eliminate the influence of time- or country-specific unobserved factors that could confound the relationship between our explanatory variable of interest and the outcome variable of corporate ESP. Furthermore, all explanatory variables – including independent variables, moderating variables, and control variables – are lagged by 1 year to eliminate the reverse causality issue.

Empirical results

Descriptive statistics and correlations

After excluding the missing information, our final sample included in the analysis comprises 9755 MNE-year observations covering 13 years, 26 countries/regions, and 66 GICS 6-digit industries. Descriptive statistics, including the mean and standard deviation, are shown in Table 3. The average value of corporate ESP is 58.825 across years and countries/regions. There is a positive correlation between climate change regulatory pressures and corporate ESP (r = 0.141). This offers initial evidence for our baseline hypothesis that climate change regulatory pressures lead to good overall ESP.

| Variable | M | SD | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Environmental sustainability performance | 58.825 | 26.036 | 1.000 | ||||||||

| (2) Climate change regulatory pressures | 8.616 | 4.961 | 0.141 | 1.000 | |||||||

| (3) Industry carbon intensity | 0.176 | 0.381 | 0.101 | 0.008 | 1.000 | ||||||

| (4) Foreign market exposure | 0.227 | 0.195 | 0.071 | −0.061 | 0.101 | 1.000 | |||||

| (5) Financial leverage | 6.062 | 24.740 | 0.037 | 0.022 | −0.052 | 0.015 | 1.000 | ||||

| (6) Price-to-book ratio | 4.698 | 22.125 | −0.024 | −0.015 | −0.037 | 0.023 | 0.152 | 1.000 | |||

| (7) Return on equity | 16.902 | 79.466 | −0.006 | 0.037 | −0.028 | −0.018 | −0.127 | −0.019 | 1.000 | ||

| (8) Firm size | 10.868 | 2.376 | 0.351 | −0.118 | −0.014 | 0.131 | 0.044 | −0.086 | −0.054 | 1.000 | |

| (9) Links with green NGOs | 0.690 | 0.463 | 0.543 | 0.076 | 0.165 | 0.066 | 0.015 | −0.008 | −0.001 | 0.177 | 1.000 |

| (10) Environmental management system | 0.561 | 0.496 | 0.399 | 0.095 | 0.136 | 0.147 | −0.041 | −0.011 | 0.006 | 0.191 | 0.227 |

| (11) Board sustainability committee | 0.777 | 0.416 | 0.583 | 0.105 | 0.138 | 0.077 | 0.012 | −0.021 | 0.013 | 0.229 | 0.410 |

| (12) Board independence | 69.222 | 24.530 | −0.062 | 0.006 | 0.019 | −0.207 | 0.030 | 0.059 | 0.026 | −0.483 | −0.005 |

| (13) Executives’ ESG-related compensation | 0.196 | 0.397 | 0.182 | 0.115 | 0.298 | −0.017 | −0.018 | 0.037 | 0.008 | −0.074 | 0.133 |

| (14) Female CEO | 0.027 | 0.161 | 0.041 | 0.045 | −0.030 | −0.035 | 0.047 | 0.002 | 0.042 | −0.027 | 0.026 |

| (15) GDP per capita | 49.760 | 12.479 | −0.072 | −0.024 | −0.052 | −0.123 | −0.003 | 0.062 | 0.009 | −0.296 | −0.036 |

| (16) Political stability | 0.646 | 0.366 | 0.048 | −0.137 | 0.058 | 0.003 | −0.021 | −0.047 | −0.024 | 0.232 | −0.000 |

| Variable | M | SD | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) | (14) | (15) | (16) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (8) Firm size | 10.868 | 2.376 | 1.000 | ||||||||

| (9) Links with green NGOs | 0.690 | 0.463 | 0.177 | 1.000 | |||||||

| (10) Environmental management system | 0.561 | 0.496 | 0.191 | 0.227 | 1.000 | ||||||

| (11) Board sustainability committee | 0.777 | 0.416 | 0.229 | 0.410 | 0.302 | 1.000 | |||||

| (12) Board independence | 69.222 | 24.530 | −0.483 | −0.005 | −0.246 | −0.070 | 1.000 | ||||

| (13) Executives’ ESG-related compensation | 0.196 | 0.397 | −0.074 | 0.133 | 0.059 | 0.169 | 0.164 | 1.000 | |||

| (14) Female CEO | 0.027 | 0.161 | −0.027 | 0.026 | −0.013 | 0.017 | 0.067 | 0.050 | 1.000 | ||

| (15) GDP per capita | 49.760 | 12.479 | −0.296 | −0.036 | −0.151 | −0.080 | 0.434 | 0.068 | 0.040 | 1.000 | |

| (16) Political stability | 0.646 | 0.366 | 0.232 | −0.000 | 0.080 | 0.057 | −0.169 | −0.077 | −0.026 | 0.306 | 1.000 |

Results of hypotheses testing

Table 4 summarizes the results of the regression analysis. Model 1 first includes all explanatory variables, presenting the baseline effect of climate change regulatory pressures. Model 2 and Model 3 each add one interaction term, namely climate change regulatory pressures × industry carbon intensity and climate change regulatory pressures × foreign market exposure, respectively. Model 4 includes all control variables, the main independent variables, and two interaction variables.

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate change regulatory pressures | 0.144** | 0.108* | 0.215*** | 0.186** |

| (0.060) | (0.063) | (0.073) | (0.074) | |

| Industry carbon intensity | −2.579*** | −4.242*** | −2.597*** | −4.451*** |

| (0.506) | (0.944) | (0.506) | (0.949) | |

| Climate change regulatory pressures × Industry carbon intensity | 0.195** | 0.217** | ||

| (0.094) | (0.094) | |||

| Foreign market exposure | 1.957** | 2.010** | 4.583** | 5.060*** |

| (0.948) | (0.948) | (1.792) | (1.803) | |

| Climate change regulatory pressures × Foreign market exposure | −0.329* | −0.381** | ||

| (0.190) | (0.192) | |||

| Financial leverage | −0.005 | −0.005 | −0.005 | −0.005 |

| (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.011) | |

| Price-to-book ratio | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.009 |

| (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | |

| Return on equity | 0.002* | 0.002* | 0.002* | 0.002* |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Firm size | 4.448*** | 4.443*** | 4.453*** | 4.449*** |

| (0.128) | (0.128) | (0.128) | (0.128) | |

| Links with green NGOs | 15.822*** | 15.832*** | 15.819*** | 15.829*** |

| (0.426) | (0.426) | (0.426) | (0.426) | |

| Environmental management system | 9.392*** | 9.361*** | 9.421*** | 9.391*** |

| (0.405) | (0.405) | (0.405) | (0.406) | |

| Board sustainability committee | 16.498*** | 16.524*** | 16.483*** | 16.510*** |

| (0.478) | (0.478) | (0.478) | (0.478) | |

| Board independence | 0.109*** | 0.108*** | 0.108*** | 0.108*** |

| (0.013) | (0.013) | (0.013) | (0.013) | |

| Executives' sustainability-related compensation | 2.519*** | 2.492*** | 2.531*** | 2.502*** |

| (0.516) | (0.516) | (0.516) | (0.516) | |

| Female CEO | 3.593*** | 3.590*** | 3.570*** | 3.563*** |

| (1.128) | (1.127) | (1.127) | (1.127) | |

| GDP per capita | 0.131*** | 0.132*** | 0.134*** | 0.136*** |

| (0.045) | (0.045) | (0.045) | (0.045) | |

| Political stability | 3.565** | 3.586** | 3.352** | 3.342** |

| (1.564) | (1.564) | (1.569) | (1.569) | |

| Constant | −35.262*** | −34.931*** | −35.909*** | −35.644*** |

| (2.766) | (2.770) | (2.791) | (2.793) | |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 9755 | 9755 | 9755 | 9755 |

| R-squared | 0.583 | 0.584 | 0.583 | 0.584 |

- Note: FE, fixed effects. Standard errors in parentheses. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

We primarily refer to Model 1 to test H1. There is a significantly positive effect of national/regional-level climate change regulatory pressures on firm-level ESP (coeff. = 0.144, p < 0.05). Additionally, the positive coefficient remains statistically significant from Model 2 to Model 4 when adding the interaction variables. Therefore, H1 is empirically supported. We can further observe a significantly positive coefficient (coeff. = 0.195, p < 0.05) in Model 2 for the interaction term of climate change regulatory pressures × industry carbon intensity. This suggests that industry carbon intensity strengthens the positive relationship between climate change regulatory pressures and ESP, thereby supporting H2. In contrast, for H3, as indicated by a significantly negative coefficient (coeff. = −0.329, p < 0.10) in Model 4 for the interaction variable of climate change regulatory pressures × foreign market exposure, we conclude that as firms’ level of foreign market exposure increases, regulatory institutions become a weaker predictor of ESP. This confirms with the prediction in H3. Notably, in Model 4, when we include two interaction terms simultaneously, two coefficients of the interaction variables remain statistically significant and consistent. This offers empirical support of our theoretical predications in the moderating hypotheses.

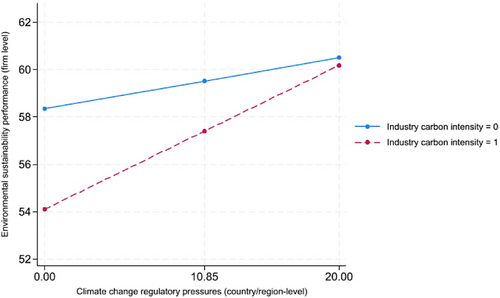

We also perform simple slope analyses for the moderating effects of industry carbon intensity and foreign market exposure. As shown in Figure 1, the slope visualizing the impact of climate change regulatory pressures on corporate ESP becomes steeper for carbon-intensive MNEs (see the maroon dashed line in Figure 2) as compared with non-carbon-intensive MNEs. Furthermore, we also examine the marginal effects (i.e. dy/dx) of moderating variables. We compute the average marginal effect for ease of interpretation, The average marginal effect of climate change regulatory pressures when the MNE is in a carbon-intensive industry is 0.303 (z = 3.130, p < 0.01), whereas the average marginal effect when the MNE is in a non-carbon intensive industry is 0.108 (z = 1.730, p < 0.10).

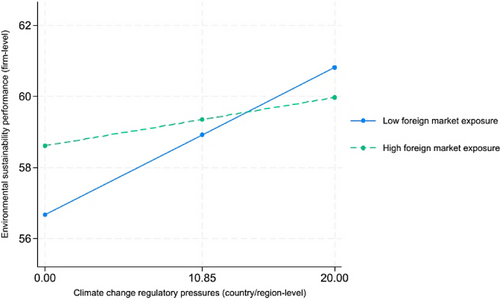

By contrast, the slope visualizing the impact of climate change regulatory pressures on corporate ESP is steeper under low levels of foreign market exposure (see the blue solid line in Figure 2), suggesting that the effect of home-country regulatory institutions on ESP is stronger when the firms’ foreign market exposure is low. The average marginal effect of climate change regulatory pressures is 0.207 (z = 2.950, p < 0.01) when foreign market exposure is low (one standard deviation below the mean), which is significantly larger than the effect when foreign market exposure is higher (0.068; z = 0.910, p > 0.10; one standard deviation above the mean).

Bolstering of causal inference

Although we use a 1-year time lag between predictor and outcome variables to address the endogeneity issue, the causal inference between national/regional regulatory institutions and corporate ESP remains to be challenged. Hence, we implement a quasi-experimental research design using an exogenous shock to bolster causal inferences, specifically the surprising 2016 electoral success of Donald Trump, who is a firm climate change denier. Trump moved into the White House and rose to power on 20 January 2017. His presidency and populist agenda have been described as ‘narrow and largely unanticipated’ (Jacobson, 2017, p. 9) and hence served an exogeneous shock to established institutions in the United States (Child et al., 2021; Wagner, Zeckhauser and Ziegler, 2018).

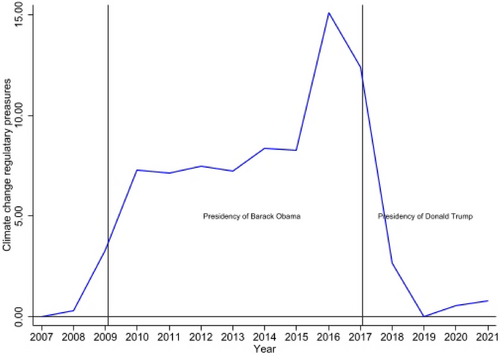

His presidency is appropriate for a quasi-experimental design for the following two reasons. First, he is publicly known for his anti-environmental beliefs. His presidency materialized the decay of emergent institutions on climate change. For instance, at the very beginning of his presidency, he publicly announced his withdrawal of the United States from the Paris Agreement, a decision that clearly embodies shrinking climate change regulatory pressures. This is also reflected in decreasing scores of Climate Policy for the United States from Germanwatch (see Figure 3). There was a significant drop in climate change regulatory pressures from the presidency of Barack Obama to that of Donald Trump. Second, narrow margins in key battleground states (namely, Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania) determined Trump's electoral success. Therefore, Trump's rise to power represents an unexpected and exogenous shock to climate change regulatory pressures. This research design also answers calls from Beamish and Hasse (2022) to leverage rare events in cross-country research.

where Post equals 1 if the observed year is after 2017 and 0 otherwise; Treatment equals 1 if the MNE is domiciled in the United States (where Trump's rise to power materialized; treatment group) and 0 (control group) otherwise. is a full set of year dummies, and is a series of firm fixed effects. Given that treatment–control classification is at the national/regional level, we also cluster robust standard errors at the national/region level (Callaway and Sant'Anna, 2021). To ensure matching quality, we use three financial variables (financial leverage, price-to-book ratio, and return on equity) and two managerial variables (board sustainability committee and board independence) to create a propensity score-matched sample to re-conduct the analysis. As reported in Table 5, the matching can ensure that there are no significant differences between treatment and control firms, thereby strengthening the comparability between the control and the treatment groups.

| Mean | Difference between (1) and (2) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Treatment (1) | Control (2) | Difference | t-statistics | p-value | |

| Financial leverage | Unmatched | 5.881 | 5.741 | 0.140 | 0.220 | 0.830 |

| Matched | 5.765 | 6.619 | −0.854 | −1.120 | 0.262 | |

| Price-to-book ratio | Unmatched | 10.007 | 3.582 | 6.425 | 6.140 | 0.000 |

| Matched | 6.224 | 6.307 | −0.083 | −0.160 | 0.874 | |

| Return on equity | Unmatched | 18.946 | 14.338 | 4.608 | 1.970 | 0.048 |

| Matched | 19.315 | 21.148 | −1.833 | −0.630 | 0.530 | |

| Board sustainability committee | Unmatched | 0.658 | 0.846 | −0.188 | −18.150 | 0.000 |

| Matched | 0.658 | 0.642 | 0.016 | 1.230 | 0.220 | |

| Board independence | Unmatched | 84.958 | 59.234 | 25.724 | 50.930 | 0.000 |

| Matched | 84.979 | 84.741 | 0.238 | 0.970 | 0.332 | |

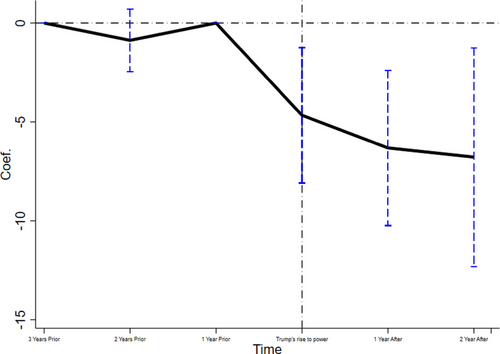

Table 6 reports the results of the different-in-differences analysis based on the full sample in column 1 and the propensity score-matched sample in column 2. We can observe significantly negative coefficients of Treatment × Post in two models, suggesting that corporate ESP in the United States worsened after the relaxation of climate change regulatory pressures exemplified by Trump's rise to power compared with MNEs domiciled in other countries/regions. This result helps strengthen the causal inference between climate change regulatory pressures and corporate ESP, providing additional support for the baseline hypothesis. With regard to the magnitude, compared with control firms, treated firms experience a drop in ESP by 3.774, which is equivalent to a drop of 15.604% (3.774/24.186) of a standard deviation of ESP (= 24.186). We have also conducted a parallel trend test, the results of which are illustrated in Figure 4. The estimated coefficients, within the 95% confidence interval, have turned significantly negative.

| Variable | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment × Post | −1.272** | −3.774** |

| (0.580) | (1.505) | |

| Foreign market exposure | −3.528 | 21.704 |

| (7.148) | (18.964) | |

| Financial leverage | 0.001 | −0.089 |

| (0.005) | (0.173) | |

| Price-to-book ratio | 0.012 | 0.022 |

| (0.009) | (0.051) | |

| Return on equity | −0.000 | 0.031** |

| (0.001) | (0.014) | |

| Firm size | −1.062* | −1.629 |

| (0.553) | (1.476) | |

| Links with green NGOs | −0.966 | −2.179 |

| (1.253) | (2.816) | |

| Environmental management system | 1.581 | −0.298 |

| (0.998) | (2.397) | |

| Board sustainability committee | 1.434 | 0.647 |

| (0.963) | (1.347) | |

| Board independence | −0.014 | 0.073 |

| (0.029) | (0.080) | |

| Executives' sustainability-related compensation | −0.405 | 0.646 |

| (0.936) | (1.796) | |

| Female CEO | 0.139 | 0.444 |

| (0.777) | (3.602) | |

| GDP per capita | 0.005 | −0.035 |

| (0.063) | (0.096) | |

| Political stability | −2.197 | −9.862*** |

| (1.437) | (2.576) | |

| Constant | 75.947*** | 77.026*** |

| (7.877) | (19.843) | |

| Year fixed-effect | Yes | Yes |

| Firm fixed-effect | Yes | Yes |

| Mean dependent variable (2014–2019) | 62.241 | 59.968 |

| Std dev. dependent variable (2014–2019) | 23.825 | 24.186 |

| Observations | 4613 | 1294 |

| Within R-squared | 0.005 | 0.035 |

- Note: FE, fixed effects. Robust standard errors, clustered at the national/regional level, are reported in parentheses. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Discussion and conclusion

Discussion of findings

In this study, we specifically examine national/regional-level climate change regulatory pressures across the globe. They share attributes with conventional regulation institutions, and furthermore have distinctiveness as ‘emergent institutions’ (Henisz and Zelner, 2005). To elaborate, these institutions have been established with the development of scientific consensus on climate change over the last three decades (Druckman and McGrath, 2019; Gupta, 2010). Also, they are susceptible to changes because of insufficient understanding of climate science, national politicized debate, and corporate lobbying activities (Kolk and Pinkse, 2008). The susceptibility-induced changes in climate change regulatory pressures can also be witnessed in the United States across two presidencies, as explained in the section on ‘Bolstering of causal inference’. Drawing on institutions theory, we provide strong empirical evidence from 33 countries over 13 years that climate change regulatory pressures, as emergent institutions, have a positive effect on corporate ESP. The causal link is bolstered in a quasi-experimental research design leveraging an exogenous shock in the United States.

Our primary finding reveals that MNEs in countries with more stringent climate change regulatory pressures have a notable enhancement in corporate ESP. The focus of this paper extends beyond the previously explored binary strategic responses (i.e. compliance/adherence or its absence) and delves into the ‘latitude in how to comply’, as highlighted by Aragòn-Correa, Marcus and Vogel (2020, p. 345). This fills an important gap in the existing body of climate change research, which, although burgeoning, lacks a detailed multi-country analysis of how climate change regulatory pressures directly impact corporate ESP. We also contribute to the literature by addressing the call from Aragòn-Correa, Marcus and Vogel (2020) to understand firm-level contingencies in responding to climate change regulatory pressures. Specifically, we uncover that the beneficial impact of climate change regulatory pressures on corporate ESP is moderated by the firm's reliance on foreign developing markets and the carbon intensity of its industry. For MNEs with higher foreign market exposure, we find that the positive impact of climate change regulatory pressures is attenuated. This may be indicative of these MNEs engaging in institutional arbitrage, thereby being less proactive in bolstering their corporate ESP (Li and Zhou, 2017; Sun et al., 2021). In addition, our results suggest a stronger positive effect of climate change regulatory pressures for firms operating in carbon-intensive industries. This implies that despite these industries' environmental challenges, the mounting regulatory pressures seem to stimulate their commitment to improved ESP. In other words, as carbon-intensive industries face more stringent climate change regulations, they tend to respond by amplifying their focus on environmental matters and improving their ESP. We therefore offer a nuanced understanding of the interplay between climate change regulatory pressures (emergent institutions) and firm-level contingencies (i.e. industry characteristics and firm-specific internationalization practice).

Furthermore, our theoretical contributions involve the integration of institutional theory with the impact of climate change. We regard climate change regulatory pressures as emergent institutions, still undergoing scrutiny and development. Consistent with Henisz and Zelner's (2005) characterization of emergent institutions, climate change regulations continue to evolve and are subject to evaluation. By empirically investigating these emergent institutions, our study offers unique insights into how firms respond to these nascent regulatory pressures. Moreover, the cross-country panel data enables us to observe changes in climate change regulatory pressures over time. Although they become increasingly intensified, the climate change regulatoty pressures can also be susceptible to external factors, such as political debate, and be eroded to some degree. We further claim that firms’ responses to emergent institutions are not time-enduring – ESP can be compromised quickly when MNEs feel a sense of change. This is in contrast to the conventional view that formal institutions and their impacts are stable by drawing attention to short-term institutional change (Mickiewicz, Stephan and Shami, 2021).

In summary, our research advances the current understanding of how climate change regulatory pressures, seen as emergent institutions, impact corporate ESP. We highlight the importance of considering both institutional and firm-level factors and provide empirical evidence for their combined effect on ESP. Our findings significantly extend the institutional theory literature, particularly as it pertains to climate change and firm-level responses to it.

Practical implications

Our findings have several implications for managers and policymakers. The results highlight the need for managers to gain a better understanding of national-level climate change regulatory pressures for the improvement of ESP. Although there have been some spaces to transfer environmental externalities through the global value chain for MNEs, they should take a cautious step in avoiding doing so because of the intensifying level of regulatory institutions across the globe. Based on our prediction, firms operating in countries/regions with higher climate change regulatory pressures are expected to have good overall ESP. This suggests that managers should view the relevant laws, policies, and regulations of climate change not just as burdens or costs but as catalysts for improving a firm's environmental sustainability practices. Moreover, as the regulatory pressures of climate change are still emerging and evolving, we encourage managers to stay informed about changes in the regulatory landscape. Monitoring these changes and adapting the response strategies proactively might help the business stay ahead of compliance issues and seize potential opportunities for improved ESP.

Meanwhile, policymakers should use various means to address climate change as an emergent entity, formulating laws, rules, and regulations to shape their country's emergent institution of climate change response. This can help to directly address the grand environmental challenge of climate change at the national level and encourage MNEs to tackle other environmental issues. Furthermore, federal governments should closely monitor internationally recognized frameworks and ensure that their approach to climate change is relatively consistent. Enshrining consistency across institutional contexts can make it difficult for MNEs to transfer their environmental externalities. For NGOs that develop internationally binding climate agreements, such as the United Nations, it is necessary to hold signed countries accountable to avoid any form of cessation from any single country, as in the case of Trump's withdrawal from the Paris Agreement. Such oversights may complicate the goal of keeping global warming below 1.5°C. Finally, it is imperative that intergovernmental organizations promote collaborations between national governments to avoid MNEs attempting to transfer their environmental externalities.

Limitations and future research agenda

This study suffers from some limitations. We have considered ESP at the aggregated corporate level, and this may overshadow the differences in the ESP level of parent and foreign subsidiaries. We encourage future studies to investigate how the differences in climate change regulatory pressures between the home country and host country affect ESP. Second, this study only considers publicly traded firms. It therefore remains unclear if the findings can be applied to small and medium-sized enterprises, which contribute substantially to GHG emissions. Third, this study assumes that climate change regulatory pressures are homogeneous in one country. It is also the case that these climate change regulatory pressures may vary across different regions within a country. This offers a valuable opportunity for future studies to investigate how sub-national regulatory pressures affect corporate ESP with more fine-grained data. Furthermore, future research should concentrate on developing a better understanding of managerial decision-making processes and explore additional contingencies beyond the two moderators discussed in this paper that impact MNEs' responses to climate change regulatory pressures.

Biographies

Xiaolong Shui is a Lecturer in International Business and Strategy at the University of Bristol Business School. His research interests reside in the areas of corporate social responsibility, with a particular focus on environmental responsibility, strategic leadership, and nonmarket strategy. His current research aims to understand the mechanisms through which firms strategically respond to grand challenges (specifically climate change) and how they can better manage their environmental impacts in light of progress towards the goal of 1.5°C.

Minhao Zhang is a Senior Lecturer in Operations Management at the University of Bristol Business School. He holds a PhD in Management from York Management School, University of York. The theme throughout Minhao's current work is data analytics in advancing the theoretical development of strategic operations and supply chain management. Thanks to various cross-disciplinary research collaborations, Minhao has published papers in the fields of supply chain management, environmental management, and big data. His work has been published in the British Journal of Management, Journal of Service Research, International Journal of Operations and Production Management, Industrial Marketing Management, Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, and International Journal of Production Economics, among others.

Yichuan Wang is an Associate Professor in Digital Marketing at Sheffield University Management School, University of Sheffield, UK. He holds a PhD in Business and Information Systems from the Raymond J. Harbert College of Business, Auburn University (USA). His research focuses on examining the role of digital technologies and information systems in influencing practices in marketing, tourism management, and healthcare management. His work has been published in the British Journal of Management, Journal of Travel Research, Annals of Tourism Research, Information and Management, Journal of Business Research, Industrial Marketing Management, IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, International Journal of Production Economics, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, and Journal of Knowledge Management.

Palie Smart's research and teaching interests are in the fields of operations and innovation management. Current research is focused on new models of innovation for industrial sustainability in partnership with the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC), MADE UK, the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, Accenture Sustainability Consulting, and the Academy of Business in Society (ABIS). She has published in various world-leading and internationally excellent journals – Chartered Association of Business Schools (CABS) and Global Top 50 Financial Times (FT) journals – which include Research Policy, Journal of Product Innovation Management, British Journal of Management, International Journal of Operations and Production Management, International Journal of Management Reviews, R&D Management, and International Journal of Production Economics.