Non-market Social and Political Strategies – New Integrative Approaches and Interdisciplinary Borrowings

The authors are very grateful to Professor Kamel Mellahi whose constructive comments have helped us to improve this paper.

Abstract

This paper introduces a special issue of the British Journal of Management on social and political strategies in the non-market environment. On the one hand, it reviews the extant research on the possible forms of interaction between Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) strategies and Corporate Political Activity (CPA): CSR-CPA complementarity, CSR-CPA substitution and mutual exclusion between CPA and CSR. On the other hand, the paper provides an overview of the recent contributions of non-business disciplines – psychology, sociology, economics, politics and history – to nonmarket scholarship and, above all, the potential future scholarly contributions of these disciplines.

This special issue addresses business strategies in the non-market environment. By their very definition, strategies in the non-market environment stand in contrast to those in the market environment. Following Baron's (California Management Review (1995), 37, pp. 47−48) definition, ‘the non-market environment consists of the social, political, and legal arrangements that structure the firm's interactions outside of, and in conjunction with, markets’, whereas ‘the market environment includes those interactions between the firm and other parties that are intermediated by markets or private agreements’. In other words, non-market strategies are about managing the wider institutional context within which companies operate, as opposed to the more narrowly economic context of market competition.

The academic dichotomy between market and non-market environments is not unproblematic. Our understanding of markets and of non-market institutions is socially constructed, and any market transaction is arguably an outcome of the social, political, cultural and economic forces that are shaping it (e.g. Abolafia, 1998; Astley, 1985; Fligstein, 1996). Some business scholars convincingly assert that, ultimately and for their benefit, companies should analyse and manage their external − market and non-market − environments in an integrated fashion (e.g. Baron, 1995; Holburn and Vanden Bergh, 2014), just as scholars of sustainable development and the social responsibilities of business suggest that companies and financial markets should integrate environmental, social and governance concerns into their day-to-day strategic decision-making for the benefit of the wider society (e.g. Busch, Bauer and Orlitzky, 2016; Elkington, 1994).

While such integrated strategies may be the ultimate goal, the study of non-market strategies is valuable and necessary. Business managers face a vast array of non-market risks and opportunities in an increasingly complicated and multi-polar world (the emergence of a relatively large number of new power centres globally), as demonstrated by various business executive surveys and consultancy reports (e.g. PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2016; World Economic Forum, 2016). In such a world, a multinational enterprise (MNE) may face an increasingly integrated international economy, on the one hand, and a fragmented non-market environment on the other (Kobrin, 2015). For example, a large MNE may decide to engage in a merger with another company to benefit from global market opportunities, but the merger deal may need to be approved by a dozen different regulatory authorities around the world. Likewise, a multinational petroleum company may have a global production system but successful production activities are dependent on different non-market actors in the different countries where the firm operates, such as different national government agencies, domestic pressure groups and so on.

Navigating this non-market environment often requires skill sets that are very different from the more conventional commercial ones, in terms of both the required political skills and capabilities (e.g. Frynas, Mellahi and Pigman, 2006; Oliver and Holzinger, 2008) and social skills and capabilities (e.g. Hart, 1995; Russo and Fouts, 1997); consequently, the study of non-market environments may require different research approaches and methods.

Rationale for this special issue

Scholarly interest in non-market strategies has existed for several decades (for recent reviews see Boddewyn, 2016; Mellahi et al., 2016). We now have considerable knowledge of the antecedents (e.g. Hillman, Keim and Schuler, 2004), the organizational performance outcomes (e.g. Rajwani and Liedong, 2015) and the contextual diversity (e.g. Örtenblad, 2016) of non-market strategies. Other recent studies have explored inter alia investor reactions to non-market strategies (Arya and Zhang, 2009; Werner, 2017) and the socially constructed nature of non-market strategies (Gond, Cabantous and Krikorian, 2017; Orlitzky, 2011) and have wondered to what extent collective political actions and private political actions are substitutes or complements (Jia, 2014).

However, research on non-market strategies has suffered from two crucial limitations. On the one hand, the relevant scholarship has been highly fragmented for a long time and has largely disintegrated into separate political and social domains. Two parallel strands of non-market strategy research have emerged in isolation: one that examines corporate social responsibility (CSR) (for a review of the CSR literature, see Aguinis and Glavas, 2012) and the other that examines corporate political activity (CPA) (for a review of the CPA literature, see Lawton, McGuire and Rajwani, 2013). Scholars have long articulated the need for an integration of these two lines of research (Baron, 2001; McWilliams, van Fleet and Cory, 2002; Rodriguez et al., 2006), but it was only relatively recently that they have started to explore this integration (see Frynas and Stephens, 2015; Mellahi et al., 2016). The lack of integration of the political and social/environmental domains of non-market strategy research manifests itself inter alia in the failure to understand the substitution effects between company political and social strategies or the failure to understand the social impact of corporate political strategies on other stakeholder groups outside the organization.

On the other hand, research on non-market strategies has suffered from the failure to integrate insights and methodologies from disciplines outside business studies such as political science, legal studies, sociology and history. While some influential theoretical lenses used in CSR and CPA scholarship originated from related disciplines outside business and management − including resource dependence theory, institutional theory and social movement theory − non-market scholarship largely imitated the application of these theories to other branches of business and management research, rather than developing them for its own purposes (cf. Suddaby, Hardy and Huy, 2011; Whetten, Felin and King, 2009). Additionally, in those instances in which borrowing did take place in non-market scholarship, its quality was sometimes poor, as notably evidenced by the superficial application of Habermasian theories to recent political CSR scholarship (see the critique by Whelan, 2012). Given that, by definition, non-market research touches on the political, legal and social aspects of company strategies, one would expect and welcome a much greater cross-fertilization with non-business disciplines in order to address those aspects of non-market strategy that are currently insufficiently explained by existing approaches.

Underlying the rationale of this special issue has been our desire to help, in a modest way, to fill these two research gaps. Consequently, we sought papers that either offer new pathways for the integration of the political and social research domains in non-market research and/or offer new pathways for the enrichment of our understanding of non-market strategies with insights and theories from outside business studies. The four papers in this special issue help to address these research gaps in very different ways.

Integration of social and political perspectives

In recent years, CSR scholarship has started to address the political aspects of CSR (for a review, see Frynas and Stephens, 2015), although many studies approached political CSR from a narrow normative research agenda, advocating a new conception of political CSR that ascribes new roles to business in the delivery of public goods, which postulates normative theory to the exclusion of descriptive theory and addresses changes in global governance to the exclusion of the traditional domestic political process (e.g. Scherer and Palazzo, 2007; Scherer et al., 2016). CPA scholarship also explored some social aspects of political activities − e.g. CPAs related to environmental regulation, such as regulation related to climate change (e.g. Kolk and Pinkse, 2007; Levy and Egan, 2003) − or the role of social mobilization in CPAs (e.g. McDonnell and Werner, 2016; Walker, 2012), but, until recently, it has largely failed to specifically explore the CSR−CPA relationship. In effect, only relatively few empirical studies have started to explore the nature of the interactions between CSR strategies and CPAs (as discussed below), and their results to date appear highly contradictory.

CPA−CSR complementarity

There has been an explicit assumption among various scholars that CSR and CPA are complementary and may need to be aligned (e.g. den Hond et al., 2014; Liedong et al., 2015). Indeed, recent empirical research suggested that CSR weakens the potentially negative impact of CPA (Liedong et al., 2015; Sun, Mellahi and Wright, 2012), that CSR helps to gain and to maintain political access (Gao and Hafsi, 2017; Wang and Qian, 2011) and, alternatively, that CPA offsets negative CSR records (Alakent and Ozer, 2014). The important conceptual papers by den Hond et al. (2014) and Rehbein and Schuler (2015) outlined the various possible ways in which CSR can strengthen CPA, and vice versa.

CPA can strengthen CSR activities through several mechanisms. Interactions with political actors can assist organizations in selecting CSR priorities by identifying significant social and political issues. CPA can provide critical information, support or favourable regulation to enhance the economic viability of CSR activities. CPA may also help to increase the credibility and legitimacy of CSR activities (den Hond et al., 2014).

Conversely, CSR can strengthen CPA by facilitating access to the political system and its efficacy. CSR can improve human capital resources (e.g. issue expertise), organizational capital resources (e.g. legitimacy) and geographic presence in a political constituency. CSR, as a CPA strategy, may also lessen the necessity for financial donations to politicians or may reduce the cost of demonstrating compliance to regulation (den Hond et al., 2014; Rehbein and Schuler, 2015).

CPA−CSR substitution

In contrast, the paper by Liedong, Mellahi and Rajwani (2017) in this special issue finds no evidence for complementarity. The authors found that CSR helps to lower perceptions of risk exposure but is ineffective when combined with managerial political ties (MPTs), thereby ‘suggesting the existence of a form of “cannibalization” whereby MPTs erode the gains of CSR’. This gives some credence to the idea that CSR and CPA may mutually act as substitutes. Other empirical research provided some evidence that, for example, companies may donate less to charitable causes because they have good political connections (Zhang, Marquis and Qiao, 2016). In this case, CPA substitutes for CSR. Another recent study found that those Chinese companies that increase CSR in the aftermath of changes of city-level mayors can build political networks and can be rewarded with government subsidies (Lin et al., 2015). In this case, CSR substitutes for CPA.

In general terms, companies may have a preference for CSR as a substitute for CPA because the latter is vulnerable to the loss of political ties due to the departure of managers with personal ties to political decision-makers (Sun, Mellahi and Wright, 2012), or because potential political and regulatory shocks and evolutionary changes may undermine the value of a company's existing political ties (Siegel, 2007; Sun, Mellahi and Thun, 2010). Most notably, the politicians or political factions in power may be displaced, thus exposing those companies that had cultivated close relations with them (Darendeli and Hill, 2016).

By contrast, CSR tends to be more politically neutral and its organizational value is more likely to outlast changes in government or managerial departures. In addition, companies with a reputation for CSR activities may also be reluctant to become involved in political activities (including even government-sponsored sustainability initiatives) because of the perceived risk of later accusations of ‘greenwashing’ and hypocrisy (Kim and Lyon, 2011).

CPA−CSR incompatibility

Some research also provided evidence that CSR and CPA may be mutually exclusive. For example, some research on philanthropy (which can be viewed as a sub-set of CSR) suggests that philanthropy may not necessarily be undertaken for rational, instrumental reasons, because it is an outcome of employee empathy (e.g. Grant, Dutton and Rosso, 2008) or because it consists of ad hoc corporate disaster relief following some catastrophic events (e.g. Crampton and Patten, 2008); hence philanthropy may not be a substitute for CPA or complementary with CPA under those circumstances. Boddewyn and Buckley (2017) in this special issue and other studies (Gao and Hafsi, 2017; Wang and Qian, 2011) suggest that philanthropy may still lend itself as a substitute for CPA or complementary with CPA, but some societal issues such as conflict mitigation and resolution may just be fundamentally unsuited to becoming part of a company's CPA agenda.

As a notable example, Jamali and Mirshak (2010) investigated the extent to which MNEs can help in conflict mitigation and resolution and peace building efforts in conflict-prone host countries. While the authors actually provided a normative argument in favour of such roles for companies in conflict-prone regions, their actual empirical evidence pointed to the incompatibility of goals and means between the social activities of MNEs and the political activities necessary to help in conflict mitigation and resolution and peace building. The surveyed companies had a fundamentally neutral and apolitical stance, had perceptions of low power vis-à-vis the conflict sides and failed to appreciate the collective interest in providing solutions to conflicts. At the same time, the companies believed that the means and expertise at their disposal were not necessarily appropriate in conflict situations. This research suggests that − at least in some areas of societal engagement − integration between CSR and CPA may be extremely difficult.

At the same time, within some companies, CSR and CPA may be seen as separate mutually exclusive activities because of existing internal organizational structures and corporate values. These underpin the development of non-market activities by companies, stemming from inter alia the structuring of business groups (Dieleman and Boddewyn, 2012), ownership structures (Lawton, Rajwani and Doh, 2013), the internal organization of the external affairs function (Doh et al., 2014) and the nature of the internal relationships between public affairs managers and colleagues in other subsidiaries (Barron, Pereda and Stacey, 2017). For example, the external affairs function at the German airline Lufthansa specifically benefitted from the complementarities of integrating social and political activities, while the creation of a similar European external affairs function at Tata Consultancy Services (an affiliate of India's Tata Group) had few consequences for political activities because its remit was strictly limited to social and environmental activities (Doh et al., 2014). Thus, we still need to learn considerably more about the effects of organizational structures and corporate values on CSR−CPA integration.

The way forward

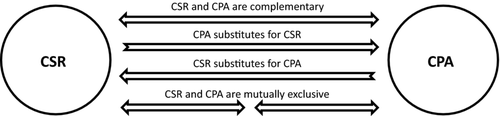

Based on the above discussion, we conclude that integration, substitution and mutual exclusion are all possible forms of interaction between corporate social activities and CPAs. Our model in Figure 1 visualizes these possible forms of interaction.

We should recognize, of course, that different types of CSR or CPA may elicit different interactions; for example, a company's high expenditure on environmental protection measures may make it redundant for it to lobby the government for lower environmental regulatory standards (substitution effect), whereas a company's expenditure on charitable projects that are valued by politicians may help to improve corporate political ties (complementarity effect). Similarly, it is possible that complementarity effects may be more likely in some institutional contexts, e.g. countries in which the government intervenes more frequently in the economy, such as China, and less likely in a country with relatively few government interventions, such as Switzerland (on China, see Wang and Qian, 2011; on Switzerland, see Helmig, Spraul and Ingenhoff, 2016).

Given that there can be much variance in CSR−CPA interactions, future research should investigate how the nature of these interactions may differ between different types of CSR and CPA, different institutional environments, different industry contexts, different types of organizations, internal organizational arrangements or individual business leaders, or how these interactions change over time.

At this stage, one can pose the fundamental question as to the extent to which we can neatly divide all corporate non-market activities into CSR and CPA, given that the political and social aspects of non-market interventions are so often intertwined. Some key characteristics enable us to distinguish CSR from CPA. Notably, CSR tends to be an open, often well publicized activity that can be imitated by others (Frynas, 2015; McWilliams and Siegel, 2011), whereas CPA tends to be conducted behind closed doors (Boddewyn and Brewer, 1994), which is more a difference of process rather than of intent. But non-market activities may be simultaneously aimed at both the political constituency and the wider society. If CSR is solely motivated by helping a company influence a government (as in the example of the casinos in the Boddewyn and Buckley paper in this special issue) or if political engagement is motivated by social and ethical concerns (as in the case of the creation of social and environmental private regulation to fill in for its inadequate state counterpart), should we treat such activity as CSR or CPA?

In addition, companies are increasingly getting involved in emotive and publicly contested socio-political issues that do not neatly fall into either the traditional CSR or CPA categories; e.g. Volkswagen's support for the influx of refugees in Germany, Lush Cosmetics’ support for LGBT education in the USA, or Ctrip's opposition to the government's ‘one-child policy’ in China (Nalick et al., 2016). Therefore, the ‘non-market’ label may ultimately be more helpful than CSR and CPA, but our concern here is with integrating CSR and CPA in scholarship and in practice in view of the fact that the two types of activities still tend to be viewed as distinct and are addressed in distinct fields of study.

Non-business insights on non-market strategies

Non-market strategies are about addressing those environmental forces that are the outcome of political, social or historical processes. However, scholarship on non-market strategies has been slow at integrating insights and methodologies from political science, sociology, history and other related disciplines. In recent years, there has been a rising interest in non-market research among psychologists (e.g. Gully et al., 2013; Rupp and Mallory, 2015) and − to a lesser extent − sociologists (e.g. Lim and Tsutsui, 2012; Walker and Rea, 2014), but there has been little interest from, say, historians or political scientists.

Mellahi et al. (2016, p. 167) noted that ‘borrowing new insights from non-business disciplines may potentially lead to some of the greatest advances in our understanding of non-market strategy’. The full promise of insights from non-business disciplines for non-market scholarship still remains unfulfilled. Therefore, it may be useful to scope out how non-market scholarship could benefit from such insights. Here, we provide a brief overview of the recent contributions of non-business disciplines to non-market scholarship and, above all, their potential future contributions. Table 1 summarizes some of the promising theoretical approaches and the related future research questions.

| Theoretical perspectives | Key research questions |

|---|---|

| Psychological theories | How do personal identities and values of the individual actors involved in non-market strategy influence CSR and CPA and interactions between them? What effect do they have on the acceptability and impact of those strategies? |

| Organizational power | How is power located and exerted in different relational frameworks? What are the power-related processes governing the implementation and evolution of non-market strategies? |

| Transaction cost economics | How does non-contractual reciprocity affect non-market strategies? How do individual transactions between companies and non-market actors reveal the nature of reciprocal exchanges, the capture of non-market actors by business, or the integration between CSR and CPA? |

| Austrian economics | How do asymmetric future expectations among individual managers affect non-market strategies or the development of social and environmental innovations? |

| Social contract | How do the nature and strength of the social contract between citizens and the state influence differences between non-market conduct and subsequently organizational performance across different national contexts? |

| Habermasian theories | How do discourses and societal power structures reveal different normative assumptions and forms of communication behind notions of organizational performance in different institutional contexts? |

| Biological theories | How can we draw parallels between organizational behaviour and biological processes to better understand the implementation and evolution of non-market strategies? |

Psychology and non-market research

According to a survey of organizational psychologists conducted by the Society of Industrial and Organizational Psychology a few years ago, CSR was one of the top trends affecting the workplace (reported in Glavas, 2016). In fact, various studies of employment relations borrowed psychological theories to explore aspects of workplace relations that are closely related to CSR (see discussion below). At the same time, business and management scholars have been making calls for more non-market research at the individual level of analysis, an endeavour in which psychological theories could play a leading role (e.g. Aguinis and Glavas, 2012; Hillenbrand, Money and Ghobadian, 2013; Morgeson et al., 2013).

Psychological research and theories already have an established presence in those micro-level studies of employment relations that have natural linkages to CSR concerns − such as work–life balance and employee voice research − and have started affecting CSR scholarship in general (Glavas, 2016; Rupp and Mallory, 2015). Examples of psychological theories that can be useful in explaining non-market factors at the individual level include, for example, cognitive categorization theory (cf. Lord and Maher 1991), organizational justice theory (cf. Greenberg, 1987), psychological contract theory (cf. Robinson, Kraatz and Rousseau, 1994) and image theory (cf. Schepers and Beach, 1998) (for an overview of such theories, see Frynas and Croucher, 2015; Rupp and Mallory, 2015). Studies have applied psychological theories to demonstrate inter alia that CSR is positively related to employee social identification with their organization (e.g. Evans et al., 2011; Jones, 2010) or that CSR signals the values of an organization − and hence the potential for value congruence − to potential job applicants (e.g. Gully et al., 2013; Jones, Willness and Madey, 2014).

Recent reviews (Glavas, 2016; Rupp and Mallory, 2015) showed that psychological perspectives on CSR are quickly gaining ground among scholars. Special issues of journals have been solely devoted to the intersection of CSR and organizational psychology (e.g. Andersson, Jackson and Russell, 2013; Morgeson et al., 2013; Rupp et al., 2015). Perhaps unsurprisingly, psychology has arguably made the greatest contribution of recent years to non-market research. One recent review in a psychology journal went as far as to suggest that ‘With the rise of employee-focused micro-CSR research, person-centric work psychology, and humanitarian work psychology (HWP), a sea change is occurring regarding the field's perspective on CSR’ (Rupp and Mallory, 2015, p. 212). This development informs the distinction between internally and externally directed CSR and their respective intentions. CSR directed toward employee well-being within the company may be primarily intended to raise productivity. CSR directed towards projects in the external society may be primarily intended to create political capital and, in this respect, be more closely allied to CPA.

A psychological perspective emphasizes that decisions on CSR and CPA activities are made and implemented either by individuals or by teams of individuals. It draws attention to the significance of the ‘micro-foundations’ of such activities in terms of the individual actors responsible for them (Fellin, Foss and Ployhart, 2015). The micro-foundations view of corporate CSR and CPA highlights the role and capabilities of those members of organizations who are the movers of these activities, together with the interactions they have both with each other and with external actors. It argues that these individual-level factors help to account for the ability of companies to formulate and sustain successful non-market policies and routines. In addition to the individuals’ capabilities and relationships, a psychological perspective highlights the personal identities and espoused values of the actors involved in CSR and CPA, which are also expected to provide the motivation for their initiatives and to colour the meaning they attach to them. The interpretations that corporate actors and those in governmental and institutional agencies place on non-market strategies are likely to have a significant bearing on the acceptability and impact of those strategies.

Insights from psychology hold the key to understanding many aspects of non-market strategies at the individual level. Given that emerging scholarship has overwhelmingly focused on CSR activities, there is an enormous potential for exploring the psychological processes behind the political activities of companies. Psychological theories could help investigate, inter alia, the psychological drivers behind CPAs or CPA−CSR integration, and the mediating and moderating effects of CPA that are related, for example, to social and organizational identity or the perceived person−organization fit. We certainly expect that future non-market research will be increasingly conducted at the individual level of analysis and will provide a much richer understanding of the underlying psychological processes.

Sociology and non-market research

Sociology has already left an important mark on non-market research. Two of the main theories used in non-market research − institutional theory and resource dependence theory − have their roots in sociology, while social movement theory and network theory have also left a mark (cf. Mellahi et al., 2016). Some of the psychological approaches in non-market research mentioned above − such as organizational justice theories (cf. Greenberg, 1987) − have roots in both psychology and sociology.

But sociology still has much to offer to the study of non-market strategies, and sociological contributions on non-market strategies have started to appear in leading sociology journals (Bartley, 2007; Lim and Tsutsui, 2012; Walker and Rea, 2014). Novel applications of sociological lenses − such as the institutional work lens within institutional theory (Gond, Cabantous and Krikorian, 2017) or systems theory from the sociology of law (Sheehy, 2017) − illustrate the potential sociological contributions to non-market research yet to come. Curiously, we did not receive any submissions to this special issue specifically from a novel sociological perspective, if we exclude the more traditional institutional theory applications.

Research into CPA in particular could benefit from the application of another longstanding perspective within sociology − namely, a focus on organizational power and the conditions under which it is exercised. While some scholarship on CSR has explicitly acknowledged the critical importance of power relations (e.g. Banerjee, 2008; Bondy, 2008), in particular within global production chains (e.g. Levy, 2008; Tallontire, 2007), it would be appropriate for the analysis of CPA to take greater account of power and of the processes whereby power is generated and used. Following Pfeffer's (1981, p. 7) aphorism that politics is ‘power in action’, a potentially fruitful approach to doing this is found in the political action analysis of corporate socio-political initiatives. This is premised on the view that power (or, more precisely, its exercise in the form of influence) does not necessarily follow mechanically from the possession of valuable resources but is also generated through persuasive actions that create legitimacy for corporate policies in the eyes of other actors. The political action perspective therefore regards the outcome of non-market strategies as depending on the process of how they are presented, interpreted and negotiated within the relational framework (the network of social and political relations that companies have with external agencies) between corporate and external actors (Child, Tse and Rodrigues, 2013). A fundamental assumption is that power operates through relationships such as these and ‘is inseparable from interaction’ (Clegg, Courpasson and Phillips, 2006, p. 6).

The political action approach within sociology draws attention to the power-related processes governing the implementation and evolution of CSR and CPA. Power is regarded as a capacity rather than as the exercise of that capacity (Lukes, 2005). In other words, a corporation's possession of a power resource gives it the potential to implement CSR and conduct effective CPA, but the outcome will depend on the dynamics of the relations with the other parties that are involved. This approach also allows for reaction and counter-action by institutional and other recipients of corporate non-market strategies. In so doing, it acknowledges the relevance of contrasting cultural and political contexts in informing that reaction. This indicates that a potentially fruitful way forward for research would be to address questions such as, for example, how power is located and exerted in different relational frameworks, or whether, in some contexts, CSR is a more effective non-market strategy than CPA and vice versa. We believe that the neglected study of power dynamics holds the key to understanding the boundaries of what is feasible in terms of implementing non-market strategies.

Economics and non-market research

Economics has already left an important mark on non-market research in the sense that many notable non-market strategy studies have applied economic analysis in conceptualizing and explicating problems in non-market research, e.g. by investigating CSR with reference to the attributes of neo-classical equilibrium models or by conceptualizing non-market choices of companies as games with specific payoffs (e.g. notable contributions by Baron, 2001; King, 2007; Kitzmueller and Shimshack, 2012). Agency theory has become one of the most influential theoretical perspectives applied in non-market research (cf. Mellahi et al., 2016).

Transaction cost economics has also left a mark on non-market research, in particular investigating the transaction cost drivers that affect companies’ governance choices with regard to CSR activities (e.g. Husted, 2003; King, 2007). Last, but not least, game theory has contributed interesting insights to non-market research (e.g. Baron, 2001; Fairchild, 2008). Finally we should remember that institutional theory also has roots in the study of the regulatory role played by institutions in economics (Davis and North, 1971; North, 1990) and this ‘new institutional economics’ lens has influenced non-market research (Bonardi, Holburn and Vanden Bergh, 2006; De Figueiredo, 2009; Dorobantu, Kaul and Zelner, 2017).

Leading literature reviews of non-market scholarship in recent years have emphasized the need for more scholarship on the micro-foundations of non-market strategies (Aguinis and Glavas, 2012; Mellahi et al., 2016), and economics can arguably play an important role in the study of these micro-foundations. In fact, agency theory has been the leading lens for the understanding of micro-level phenomena in non-market research to date. Micro-level studies conducted through the agency theory lens have inter alia investigated the link between CEO compensation and levels of CSR performance (e.g. Berrone et al., 2010; Deckop, Merriman and Gupta, 2006) and the link between the individual characteristics of top management team members and CSR-related decision-making (e.g. Bear, Rahman and Post, 2010; Chin, Hambrick and Treviño, 2013). However, agency theory has a relatively narrow focus on agent−principal relationships and hence provides only a partial explanation of non-market strategies.

The article by Boddewyn and Buckley (2017) in this special issue inspired us to think that the micro-foundations of non-market strategies could be studied by looking at individual non-market transactions. Instead of studying the individual traits of decision-makers (using psychological theories or agency theory) or the relationships between an organization and its individual stakeholders (using stakeholder theory or resource dependence theory), future researchers could apply the tools provided by transaction cost economics to study individual transactions at the micro-level, e.g. the individual transactions that occur between companies and non-governmental organizations or the individual transactions conducted by corporate charitable foundations. Such analysis could provide a wealth of insights on issues such as the nature of reciprocal exchanges, the capture of non-market actors by business, and the integration between social and political strategies.

Going beyond neo-classical economics, Austrian economics provides one alternative avenue for enriching individual-level perspectives on non-market strategy. In contrast to neo-classical economics and much of the extant non-market literature, Austrian economics regards human action − not external constraints − as fundamental to decision-making (e.g. Lachmann, 1956; Mises, 1963). While Austrian economists such as Mises (1963) viewed consumer demand as an external constraint, they suggested that the only acceptable research propositions are those relating to individual actions, and that all motivations of agents and institutions arise from individual behaviours (applying the Austrian concept of ‘methodological individualism’). Austrian economics can provide a superior explanation for individual decisions, recognizing that inter alia value is subjective, manager-entrepreneurs can choose different courses of action, and information is interpreted differently by different actors (the Austrian concept of ‘asymmetric expectations’). The few studies that applied Austrian economics to CSR (Adams and Whelan, 2009; Frynas, 2009; Maxfield, 2008) had no discernible influence on wider non-market scholarship, but non-market studies from an Austrian perspective could investigate inter alia asymmetric future expectations among individual managers with regard to non-market environments or the genesis of social and environmental innovations in companies as a result of entrepreneurial/intrapreneurial decision-making. Insights from Austrian economics have informed the micro-level perspective of the resource-based view in strategic management (Foss and Ishikawa, 2007; Kraaijenbrink, Spender and Groen, 2010) and, conversely, there may be much value in applying Austrian economics to inform the micro-foundations of non-market behaviour.

Political science and non-market research

There is a long scholarly tradition pertaining to the investigation of the interactions between business interest groups and politics (Gerschenkron, 1943; Schattschneider, 1935) and, specifically, company-level CPAs (for an early review, see Shaffer, 1995; for a review of the recent CPA literature, see Lawton, McGuire and Rajwani, 2013). Political frameworks have influenced CPA and CSR research, as evidenced inter alia by the use of political economy ideas in the scholarship on business and politics, the application of the social contract concept in business ethics and the reliance on Habermasian political theory in political CSR research.

Influenced by pluralist theory scholarship in international relations (cf. McGuire, 2015), political economy ideas and concepts have found their way into business and politics research, helping to explain the increased structural power of companies in politics (e.g. Farrell and Newman, 2015; Fuchs and Ledererer, 2007). Influenced by the concept of the social contract in political theory (cf. Frynas and Stephens, 2015), the social contract has been applied to issues of business ethics and CSR, particularly in the form of Donaldson and Dunfee's integrative social contracts theory, as a way of explaining and legitimizing the non-market (political and social) involvement of business without reliance on state regulation or indeed a legitimate state (e.g. Hartman, Shaw and Stevenson, 2003; van Oosterhout, Heugens and Kaptein, 2006). However, we must note that insights from political economy have largely failed to inform the CPA literature, just as social contract approaches have largely failed to inform the CSR literature, in the leading mainstream business journals.

In this context, the ‘political CSR’ research stream has recently made a very important contribution by encouraging a wider discussion of corporate political engagement in business schools and in mainstream business journals. Inspired by and selectively borrowed from the political writings of Jürgen Habermas (cf. Whelan, 2012), Scherer and Palazzo (2007, 2011) offered a normative political CSR conception, portraying a vision of a global society in which non-state actors legitimately provide public goods to satisfy human development needs. They adopted the Habermasian political concept of ‘deliberative democracy’ as a way of addressing the legitimacy gap created by the involvement of non-state actors in political decision-making. Scherer and Palazzo's conception has attracted considerable follow-up work (e.g. Levy et al., 2016; Lock and Seele, 2016; Scherer et al., 2016).

However, there was a notable absence of political scientists in political CSR debates, Habermasian ideas were incompletely adapted and normative political CSR scholarship failed to offer any predictive power (see the critique by Whelan, 2012). The lack of involvement of political scientists manifested itself, for example, in the axiomatic misconception of this literature with regard to the decline of state power as a key explanation of non-market strategies, despite evidence from political science that state power vis-à-vis companies remains strong and is a prerequisite for successful economic globalization (e.g. Evans, 1997; Kim, 2013; Micklethwait and Wooldridge, 2014; Weiss, 2000).

We are left with the impression that political theory has still failed to fulfil its full promise with regard to informing non-market scholarship. Going beyond their function in business ethics research, social contract theories could be applied to study, for instance, how the strength of the social contract between the state and its citizens across a multinational company's different host countries serves to either legitimize or delegitimize non-market strategies and affects the success and failure of such strategies. Going beyond normative political CSR research, Habermasian ideas could help us to understand, inter alia, how different discourses around non-market issues may be manipulated by the media, the companies and governments with different vested interests, yielding deeper insights that are currently unavailable through applied linguistic analysis. In more general terms, insights from political theory and international relations can help to explain political changes at the domestic and global levels that affect the non-market arena inter alia much beyond the currently popular institutional theory that is unable to effectively explain the structural causes of global institutional changes (cf. Wood, Dibben and Ogden, 2014).

History and non-market research

Business history directly informed the birth of some business disciplines in the 20th century in that detailed historical evidence informed inter alia John Dunning's OLI paradigm in international business (Jones and Khanna, 2006) and Alfred D. Chandler's ideas in strategic management (Witzel, 2012, pp. 164−165). However, as the influence of business history has gradually waned in business and management generally, its contribution to the development of non-market strategy scholarship has also been negligible.

We believe that historical evidence could significantly enrich our understanding of non-market strategies, not least since the development of non-market resources by companies has been shown to be linked to long-term cooperative interactions and reciprocity by the actors involved (Frynas, Mellahi and Pigman, 2006; Sun, Mellahi and Thun, 2010). In line with those historians who have pointed to the benefits of robust longitudinal historical case studies in business research (Carr and Lorenz, 2014; Jones and Khanna, 2006), we think that non-market strategy research could fruitfully utilize such studies to investigate how companies acquire, integrate and sustain political and social resources and how non-market strategies evolve in the long term.

As Morck and Yeung (2007, pp. 358−359) suggested, historical evidence has the great merit of uncovering the direction of causality, given that ‘any causal explanation must be consistent with both time series and cross-sectional variation’. Robust historical case studies can be instrumental in understanding causality, especially if abundant case studies are available across a panel of data. By extension, historical research could help to address, inter alia, one of the most studied and still ambiguous concerns in non-market strategies: the nature of the non-market strategy−performance link (cf. Mellahi et al., 2016). Historical case studies of a large number of companies could help us to confidently answer the question obscured by statistical data: whether non-market strategies lead to positive organizational performance or − as suggested by some writers − that it is actually above-average organizational performance that enables managers to spend corporate funds on non-market initiatives, often as personal perquisites.

The very few available journal articles on CPAs and CSR that painstakingly utilize evidence from historical archives (Decker, 2011; Frynas, Mellahi and Pigman, 2006; Harvey, 2016) point to the potential of historical sources for advancing non-market research. Frynas, Mellahi and Pigman's (2006) historical evidence on the political activities of British oil companies under colonialism demonstrates how archival sources (e.g. confidential letters and memos) can tell us what motivated government officials to support some business interests, which can provide a more honest picture of personal motivations that would be scarcely possible through the use of interviews. Harvey's (2016) historical case study of coal mining safety in 19th century Britain demonstrates the closeness of social responsibility concerns and the political ties of companies, which can provide a comparative reference to today's ahistorical debates on political CSR. History has surely much to offer to non-market scholars.

Contributions in this special issue

The first paper in our special issue by Boddewyn and Buckley (2017) provides a new take on transaction cost economics in conjunction with relational-model theory, which helps to provide an explanation of how goods can be obtained from others without using transactions – namely through non-contractual reciprocity. The authors demonstrate how the concept of reciprocity can provide a fruitful way for integrating social and political strategies given that CSR strategies such as philanthropy and CPA strategies such as lobbying share the feature of donating valuable resources to non-market recipients. The contribution by Boddewyn and Buckley (2017) is particularly valuable as it allows for future researchers to investigate the interactions between social and political aspects of non-market strategy with a novel approach at the micro-level.

The next paper by Shirodkar, Konara and McGuire (2017) utilizes the institutional theory in tandem with the organizational imprinting lens to contend that MNEs founded in countries with stronger regulatory institutions are likely to spend more on lobbying in a host country compared to MNEs founded in countries with weaker regulatory institutions. While institutional theory cannot explain why MNEs act on the basis of some institutional influences but not others, the imprinting theory provides a missing explanation for why home-country institutional influences may imprint themselves on organizations. In general terms, this paper demonstrates how non-market strategy research can benefit from applying theories with origins in the natural sciences (imprinting theory originated in biology) with regard to providing a better understanding of the evolution of non-market strategies.

The third paper by Liedong, Mellahi and Rajwani (2017) integrates social capital and institutional theories to investigate the efficacy of MPTs and CSR in institutional risk reduction. Using survey data from 179 firms in Ghana, the authors find that, whereas CSR reduces institutional risk exposure, MPTs do not. Furthermore, Liedong, Mellahi and Rajwani show that the effect of MPTs on risk exposure is moderated by public affairs functions, but contrary to the extant literature there is no corroborative evidence of complementarity between MPTs and CSR – contrary to the assumptions of previous scholars such as den Hond et al. (2014) and Rehbein and Schuler (2015).

Drawing on the resource dependence theory and the resource-based view, the fourth paper by Ahammad, Tarba, Frynas and Scola (2017) investigates the interactions between market and non-market activities of firms in the context of the post-merger integration phase in cross-border mergers and acquisitions (M&As). Based on a cross-country survey of 111 M&A practitioners, the authors went beyond current research on non-market strategy in M&As by considering both political and social aspects of non-market strategy in their research design. The authors concluded that, among other things, adaptability in the non-market environment is positively correlated with adaptability in the market environment, and in turn adaptability in the market environment leads to positive organizational performance of a cross-border M&A, thus providing further support for the value of the alignment between market and non-market activities and filling a gap in the extant literature on the market−non-market interactions in post-merger integration.

In different ways, these four papers fulfil the aims of this special issue and help to provide novel insights for non-market research. The Boddewyn and Buckley (2017) paper demonstrates how a theory from economics (i.e. transaction cost economics), which has already been used in non-market research for a long time, can provide very novel insights, while the paper by Shirodkar, Konara and McGuire (2017) demonstrates how a theoretical lens with origins in biology (i.e. imprinting theory) that has rarely been mentioned in non-market research can yield key missing insights, too. In more general terms, we think that both economics and biology may still have much to offer non-market researchers – we can think of Austrian economics or the theory of autopoiesis, for example. But ultimately, we think that non-market researchers would greatly benefit from actually collaborating in joint research projects with non-business specialists, who will inevitably have a superior understanding of non-business theories and methodologies. We believe that we need to keep breaking down disciplinary boundaries, since genuine interdisciplinary cross-fertilization can be potentially invaluable.

The papers by Liedong, Mellahi and Rajwani (2017) and Ahammad, Tarba, Frynas and Scola (2017) provide some novel insights on the integration of social and political strategies and the integration of market and non-market strategies. But they have practical implications too. They suggest, for example, that complementarity effects between CSR and CPA cannot be taken for granted and the efficacy of such complementarity may fundamentally differ between different developing/emerging markets, and that managers may want to consider to what extent certain non-market strategies are appropriate in M&As at different points in time because the critical resources required for M&A success may greatly differ between different phases of the M&A process. We surely need more insights of this nature to move the non-market research forward. We simply hope that, in its modest way, our special issue will stimulate more research that will utilize novel approaches and provide more integrative perspectives.

Biographies

Jędrzej George Frynas is Professor of CSR and Strategic Management at Roehampton Business School, University of Roehampton, London, UK. He is the author or co-author of several books, including Beyond Corporate Social Responsibility – Oil Multinationals and Social Challenges (Cambridge University Press, 2009) and Global Strategic Management (3rd edition, Oxford University Press, 2014), and he published in leading scholarly journals such as the Journal of Management, Strategic Management Journal, International Journal of Management Reviews and African Affairs.

John Child is Professor of Commerce at the University of Birmingham and Professor of Management at Plymouth University, UK. In 2006, he was elected a Fellow of the British Academy [FBA]. His papers have appeared in many international journals. Among his 24 books, Corporate Co-evolution, co-authored with Suzana Rodrigues, won the 2009 Terry Book Award of the Academy of Management. His current interests focus on hierarchy in organizations and society, and the internationalization of SMEs.

Shlomo Y. Tarba is a Reader (Associate Professor), Head of Department of Strategy & International Business, and a member of Senior Management Team at the Business School, University of Birmingham, UK, and a Visiting Full Professor of Strategy at Coller Business School, Tel-Aviv University, Israel. His research interests include agility, organizational ambidexterity, cross-border mergers and acquisitions, and resilience. Dr. Tarba has published in the Journal of Management, Journal of Organizational Behavior, Human Relations, Academy of Management Perspectives, California Management Review, Human Resource Management, British Journal of Management, Journal of World Business and others. His consulting experience includes biotechnological and telecom companies, as well as industry associations such as the Israeli Rubber and Plastic Industry Association, and the US–Israel Chamber of Commerce.