Materializing Strategy: The Role of Comprehensiveness and Management Controls in Strategy Formation in Volatile Environments

Abstract

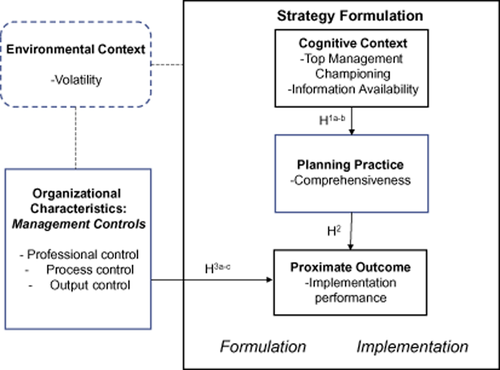

Drawing on the Mintzbergian perspective of strategy formation and strategy as practice literature we explore management controls (MCs) and comprehensiveness as antecedents to how strategy materializes in volatile environments. We focus on middle managers (MMs) since their role in strategy formation is well acknowledged. We contribute to the literature by arguing that MCs are central to strategy formation due to their role in shaping emergence of strategy and supporting implementation of deliberate strategies, with formal (process and output) and informal (professional) controls being salient micro-mechanisms in how strategy materializes in volatile environments. Specifically we argue that process control may hamper the materialization of strategy but that output and professional control aid it. We also develop the literature by arguing that comprehensiveness embeds both formally planned and emergent aspects in strategy formation, the latter enabled by top management championing and information availability which shapes MMs' predisposition to strategizing. With a quantitative study we test our hypotheses regarding championing, information availability and comprehensiveness; and comprehensiveness, and MCs and implementation performance. Our results show that comprehensiveness, output and professional controls positively influence MMs' implementation performance and, together, our antecedents reinforce each other in the materialization of strategy, hence providing an empirical contribution to the literature.

Introduction

In this paper we explore how strategy materializes in organizations operating in volatile environments and specifically address the question: what are some of the antecedents that help materialize strategy? Strategy materializes at the point of implementation (Raes et al., 2011) and is the outcome of ‘all kind of stuff’ (Whittington, 2007) that strategy making involves. This means that to understand how strategy materializes we need to examine how it is developed, i.e. both the deliberate and emergent processes (Mintzberg and Waters, 1985), and how it is implemented. To develop our argument and investigate how strategy materializes, we draw not only on the strategy formation literature but also on the strategy as practice (SAP) perspective, for which strategy is what people do. Taking these perspectives means that we consider the materialization of strategy as being both planned and emergent and as a social accomplishment. This implies that managerial perceptions of the environmental and organizational context and the interactions between organizational members are critical to understand how strategy is materialized, i.e. how it actually happens. Understanding strategy formation is a key SAP concern (Sminia and de Rond, 2012); however, there is a lack of understanding of the micro aspects of strategy emergence (Vaara and Whittington, 2012). There is also a lack of studies on implementation despite the fact many organizations fail for implementation reasons rather than formulation reasons (Hickson, Miller and Wilson, 2003; Raes et al., 2011). For this reason it is critical to understand the aspects of strategy formation which influence implementation performance, i.e. the quality of the materialized strategy.

To address our research question and capture both deliberate and emergent strategy processes we examine two aspects of strategy formation, comprehensiveness and management controls (MCs), and hypothesize that they may aid or hinder how strategy materializes. We suggest that both MCs and comprehensiveness need to be examined because, as we will explain, they illuminate strategy formation from a deliberate and emergent perspective, are information-based processes and involve top and middle management interactions. They form the context in which managers operate and thus guide managerial agency, influencing behaviour and impacting on whether strategy is successfully materialized. Moreover, these variables allow us to focus on the ‘micro’, i.e. what people do, and relate to strategy outcomes (Johnson, Melin and Whittington, 2003).

Comprehensiveness is defined as ‘the extent to which an organization attempts to be exhaustive or conclusive in making and integrating strategic decisions’ (Fredrickson, 1986, p. 474). In other words it reflects the extensiveness of strategy planning activities (Boulton et al., 1982; Lindsay and Rue, 1980). We use comprehensiveness to assess actual planning practice because it is a well-acknowledged measure of rational strategic planning (Atuahene-Gima and Li, 2004; Forbes, 2007; Fredrickson, 1986) and includes not only formally planned and but also emergent factors. It is important to study the actual activities undertaken to establish comprehensiveness since previous studies are inconclusive about whether comprehensiveness produces improved performance in volatile environments (Andersen, 2004; Bourgeois and Eisenhardt, 1988; Forbes, 2007; Meissner and Wulf, 2014) and because planning is one of the most used strategy tools (Spee and Jarzabkowski, 2009). However, studies highlight that in volatile environments organizations face complex information processing requirements necessitating organizational designs to incorporate strategic processes, control systems or communication patterns which allow for real-time information collection and interpretation (Atuahene-Gima and Li, 2004). We focus on MMs' perceptions of top management championing and information availability as sources of comprehensiveness because, by stimulating exchanges between top managers (TMs) and MMs, they form the cognitive context in which strategic issues are perceived and diagnosed (Daft and Weick, 1984; Hutzschenreuter and Kleindienst, 2006). We do so as, by virtue of their role, MMs underpin this process and viewing strategy as socially accomplished requires studies of managerial perceptions (Kaplan, 2011). In short, by impacting MMs' strategic understanding of the environment, perceptions help or hinder coordination and integration of strategy activity (Vilà and Canales, 2008).

To develop more insights into how strategy materializes we explore another aspect of strategy formation: management controls (MCs). MCs are central to strategy formation as they shape the emergence of strategy and help support the implementation of deliberate strategies (Gond et al., 2012; Marginson, 2002). While formal controls aid the achievement of deliberate strategies, informal controls provide input into the emergence of strategy (Gond et al., 2012). However, MCs may also be detrimental to strategy materialization. MCs that allow too much undirected autonomy face the risk of employees engaging in undesirable activity where interdependent activities become uncoordinated and conflictual (Davila, 2005). At the same time, if MCs constrain experimentation and fail to identify and nurture beneficial variations, then the organization may forgo potential strategic opportunities. With this in mind, we develop hypotheses to explore the impact of both formal (process and outcome) and informal (professional) MCs on implementation performance within volatile environments. We also study MCs because their role in the materialization of strategy is under-studied (Kownatzki et al., 2013; Tucker, Thorne and Gurd, 2009).

Strategy implementation performance is our proximate strategy outcome, as strategy materializes in organizations when it is executed (Raes et al., 2011). Put differently, implementation is about carrying out the strategy, resulting in the actual materialized strategy, and implementation performance is the degree to which individual managers perceive the implementation effort as successful in meeting the goals and objectives of their role (Noble and Mokwa, 1999). Implementation performance is important as the materialized strategy may not be the desired one but rather a source of failure (Nutt, 1999).

We have two boundary conditions. Our first is the context of organizations operating in a volatile environment. Volatile environments are characterized by high competitiveness and fast changing technological developments (Armstrong, 1982; Hopkins and Hopkins, 1997). Studies on strategy formation in such environments have delivered mixed results (Fredrickson, 1986; Fredrickson and Mitchell, 1984; Slater, Olson and Hult, 2006) and few have examined the important relationship between MCs and implementation outcomes. Our second is the focus on MMs. MMs are sources of emergent strategy (Wolf and Floyd, 2013) and are critical to strategy implementation (Floyd and Wooldridge, 1992, 1994). While there are many definitions of MMs (see Currie, 1999; Dutton and Ashford, 1993; Jarzabkowski and Balogun, 2009), we refer to MMs as functional managers who are concerned with product-market strategy, i.e. the way a firm chooses to position itself against its competitors (Day, 1994; Zott and Amit, 2008). MMs' decentralized role is critical in volatile markets where new product developments are frequent, since MMs are closer to the market, providing them access to critical information and prompting higher quality decisions, and also have the autonomy to take new initiatives forward, allowing the organization to quickly respond to changing market conditions (Andersen, 2004; Floyd and Wooldridge, 1997; Guth and MacMillan, 1986).

We address our research question using data from a sample of MMs in 701 organizations operating in volatile environments. Our paper provides valuable insights into how strategy materializes in this context. Specifically, we contribute to the Mintzbergian perspective of strategy formation, which argues that strategy is both deliberate and emergent by advancing that, when considering how strategy materializes, one should study MCs and comprehensiveness. They are elements of the context within which MMs implement strategy and both are factors influencing the development of deliberate and emergent strategies. Based on our integrative literature review, we develop our hypotheses, and argue that process controls may hamper the materialization of strategy in volatile environments whereas output and professional control aid it. Our argument puts to the fore that professional controls, as part of a control system, are key to how strategy materializes. Professional control is a form of social control based on individuals' knowledge and experience which allows them to apply their expertise independently in conditions of uncertainty (Abernethy and Stoelwinder, 1995). Output control too confers greater autonomy in strategy formation whereas process control relies on explicit monitoring and evaluating which constrains resourcefulness in strategy formation (Ouchi, 1979) necessary in conditions of uncertainty. We contribute to the strong scholarly research which stresses that strategizing is a social accomplishment (Jarzabkowski and Balogun, 2009; Whittington, 2004) by underlining the importance of MCs, a factor not yet examined in this context, and by emphasizing the flexibility embedded in comprehensiveness that is derived from ‘human’ aspects: TMs' championing and information availability. Finally we make an empirical contribution by quantitatively testing the impact of MCs and comprehensiveness on implementation performance. Our results reveal that comprehensiveness and output and professional control have a positive impact and that these antecedents are complementary.

Theoretical background

The Mintzbergian perspective of strategy formation is concerned with how strategies are formulated and implemented and emphasizes that strategy formation is both deliberate and emergent (Eisenhardt and Zbaracki, 1992; Mintzberg and Waters, 1985). Mintzberg (1987) explains that strategy emerges as a coherent pattern of collective activities through the actions of multiple participants. In this literature it is emphasized that strategy formation is shaped by the organizational and environmental context (Pettigrew, 1997) and that cognitive context shapes strategists' perception and diagnosis of strategic issues (Chakravarthy and Doz, 1992; Mintzberg and Waters, 1985). From a Mintzbergian perspective the way individuals interpret their context is a source of emergence and the materialized strategy results from both these emergent processes and planned rational design.

Strategy formation is key to SAP (Sminia and de Rond, 2012): strategy is not what an organization has but what people do (Johnson et al., 2007). SAP is concerned with everything involved in the formulation of deliberate strategy, the emergence of strategy and strategy implementation. This reflects the interest in both Mintzberg's (1987) pattern of decisions and of actions. However, while the formation and SAP literature is rich and many insights have been gained on strategy development and formulation/planning (Burgelman, 1983; Slevin and Covin, 1997; Spee and Jarzabkowski, 2009) little attention has been given to strategy emergence (Vaara and Whittington, 2012) and implementation (Hutzschenreuter and Kleindienst, 2006; Tamayo-Torres, Verdú-Jover and García-Morales, 2012). Existing research (e.g. Sillince and Mueller, 2007; Stensaker and Falkenberg, 2007) has concentrated on the MMs' role and sensemaking rather than on implementation performance. This may seem surprising as with no implementation no strategy is materialized and as poor implementation is the source of many organizational failures (Hickson, Miller and Wilson, 2003; Nutt, 1999). Phrased differently, implementation performance is linked to organizational performance (Raes et al., 2011) and is thus a key strategic management concern (Johnson, Melin and Whittington, 2003).

Drawing on this, in explaining our conceptual model (Figure 1) and then developing our hypotheses, we now address our research question: what are some of the antecedents that help materialize strategy? Herein, our inquiry is twofold. We examine comprehensiveness and MCs as antecedents to implementation performance.

Materializing strategy: strategy formation and management controls in volatile environments

Conceptual framework

Comprehensiveness is key to understanding how strategy materializes as it affords the examination of both deliberate and emergent aspects of strategy formation. Additionally, there remains a long standing question as to whether it enables firms to make better decisions in various environmental contexts (Bourgeois and Eisenhardt, 1988; Fredrickson, 1984), particularly volatile ones (Forbes, 2007; Miller, 2008; Meissner and Wulf, 2014) where it may not be possible to develop a perspective of the future and formulate explicit objectives, since these environments are unpredictable, ambiguous and uncertain (Idenburg, 1993).

Comprehensiveness reflects the extensiveness of the planning activity (Boulton et al., 1982; Lindsay and Rue, 1980). It concerns an organization's executives' attempts to be exhaustive in their systematic gathering and processing of information from the external environment in making strategic decisions (Fredrickson, 1984; Glick, Miller and Huber, 1993). It is a measure of planning: a bundle of strategy planning practices, tools and techniques for analysing competitive environments, target setting, organizing, communicating and budgeting (Wolf and Floyd, 2013). We argue that comprehensiveness embeds both formality, most usually conceptualized through the use of quantitative analytical techniques (Dean and Sharfman, 1993; Slater, Olson and Hult, 2006), and flexibility, allowing the development of multiple options through extensive scanning and adaptation to new information with the objective of alignment. Flexibility is maintained through MMs choosing the most appropriate option amongst alternatives, defining the details of the strategy, and having contingency plans to fall back upon (Hughes et al., 2006; Slater, Olson and Hult, 2006).

This argument is based on the formation and SAP literatures which are grounded in a Mintzbergian perspective. Here planning is contended to be a tool for integrating hierarchical layers and coordinating centralized and peripheral sources of strategy (Jarzabkowski and Balogun, 2009; Ketokivi and Castañer, 2004). It is thus viewed as embedding both formality and flexibility (Vaara and Whittington, 2012), and a means through which agents can creatively interpret and adapt strategy (Raes et al., 2011). This suggests that there is both formality and flexibility within comprehensiveness as a measure of planning. In volatile environments, organizations cannot rely on a stable core of norms, expectations and routines for planning (Miller, 2008). Such environments require flexible responses and comprehensiveness allows for the generation of such responses. Flexibility develops through the interactions of TMs and MMs and is necessary in conditions of uncertainty and ambiguity to allow for organizations to adapt to changing conditions (Jarzabkowski, Lê and Feldman, 2012; Mantere, 2005; Spee and Jarzabkowski, 2009).

To understand why emergence is embedded in comprehensiveness, one needs to examine the sources of this emergence. Given our emphasis on micro activities and the human aspects of strategy formation we consider the impact of TMs' championing and information availability as these are linked to MMs' capacity for processing and interpreting information and influence the alignment of formulation and implementation. They represent important task-specific elements of the environment, which form part of MMs' cognitive context and influence comprehensiveness through the interactions of actors. Since previous studies illustrate comprehensiveness as a mediator between managerial cognition and firm performance (Glick, Miller and Huber, 1993; Miller, Burke and Glick, 1998), in our exploration of materialization we hypothesize that comprehensiveness mediates the influence of these aspects of MMs' cognitive environment on implementation performance. Championing and provision of information for strategy formation increases MMs' understanding and commitment to the strategy (Raes et al., 2011). As seen, Mintzberg and Waters (1985) argue that the way individuals interpret their context is a source of emergence. TMs' championing through choice and selective nurturing of initiatives is important since this shapes the direction of strategy by signalling preferences for intelligence gathering and indicates acceptable courses of action consistent with the overall business strategy (Peljhan, 2007). TMs' championing indicates what is important in the organization and hence influences MMs' cognitive context. Since organizations are viewed as information processing systems that scan and collect data from their environments, interpret the data and learn by acting upon interpretation (Daft and Weick, 1984), information availability is an aspect of MMs' cognitive environment that directly affects their ability to formulate strategically relevant causal understanding (Forbes, 2007). The quantity and ambiguity of information available are characteristics that have implications for MMs' information processing and use.

We explore how comprehensiveness impacts implementation performance by highlighting that it permits both a deliberate and emergent approach to strategy formation, balancing the need for formal analytical analysis with reflection, experimentation and learning. Based on extensive scanning and adaptation of activities relative to new information, an understanding of the resources required and of their effective allocation for implementing the most appropriate alternative option is facilitated. This results in a closer alignment with target objectives and acknowledges the need for the reassessment of objectives for firms operating in volatile environments (Krohmer, Homburg and Workman, 2002; Mintzberg and Waters, 1985; Morgan, Clark and Gooner, 2002; Ramanujam, Venkatraman and Camillus, 1986).

MCs are the other antecedent we consider in our quest to explore how strategy materializes. MCs are a means of conceptualizing the control context in which MMs operate, shaping their interpretation of the internal environment and promoting the encouragement or constraint of real-time information collection (Atuahene-Gima and Li, 2004; Daft and Weick, 1984), hence influencing their actions and degree of goal congruence (Gani and Jermias, 2012). MCs are designed to influence the development and implementation of business strategies (Daft and Macintosh, 1984; Ittner and Larcker, 1997; Marginson, 2002). Traditionally, MCs have reflected relatively formalized mechanisms for strategy formation where objective criteria and procedures are imposed and behaviour is controlled through monitoring and feedback (Menon et al., 1999; Simons, 1991). Such a diagnostic approach to control criteria helps ensure strategies are appropriately supported with required resources and can assist in promoting intelligence gathering through established processes (Chenhall, Kallunki and Silvola, 2011). Formal MCs are purportedly well suited for monitoring the implementation of intended strategies (Osborn, 1998), where perceptions of market uncertainty pressure managers to review and fine-tune the scope of their intended strategies (Chari et al., 2014). Conversely, informal control is desirable in rapidly changing environments (Chenhall, 2003; Osborn, 1998), as formal controls cannot cater for the unpredictability of complex work demands (Abernethy and Stoelwinder, 1995). Informal MCs become a means for surfacing and acting upon potential emergent strategies on a day-to-day basis (Osborn, 1998; Simons, 1991) and as such should be considered when exploring emergence from a SAP perspective. Discussion and collaboration are key to such mechanisms and rely on MMs' experience and expertise. Consequently, MCs, as part of the organization's internal context, help frame MMs' belief system, and specifically what is important is MMs' perception of them (Boulton et al., 1982); these perceptions guide behaviour (Frigotto, Coller and Collini, 2013; Marginson, 2002). Within volatile environments we therefore suggest that exploring both formal and informal controls allows us to shed light on how stability and flexibility might be reconciled and maintained since, in addition to comprehensiveness, these are core to strategy formation within volatile environments. We argue that they are micro-level mechanisms that can foster or inhibit strategy emergence (Osborn, 1998), affect managerial agency and, in turn, the materialization of strategy.

In short, we are interested in the contribution of formal and informal MCs to the implementation of intended strategies and for the stimulation of emergent strategy. Whilst formal controls are beneficial for disseminating intended strategy from above, by translating into action plans, monitoring the implementation of these plans and identifying deviations for corrective action, informal controls encourage experimentation, support variations in day-to-day responses and structure interactions that facilitate the exchange of knowledge (Davila, 2005; Simons, 1991). MCs must allow for flexibility, so that MMs can respond quickly to changes in the environment, but also for stability so that they are able to learn, allowing the organization to grow based on its strengths (Osborn, 1998).We develop our hypotheses based on this framing.

Hypotheses development

Strategists' cognitive context and comprehensiveness

MMs' perceptions of their context influence their behaviour (Collier, Fishwick and Floyd, 2004; Daft and Weick, 1984) and offer a source of emergence (Mintzberg and Waters, 1985). Our constructs representing MMs' cognitive context, championing and information availability, acknowledge that strategy is socially accomplished through the actions of multiple participants (Jarzabkowski, 2005) and help illuminate how strategy materializes by exploring how championing and information availability shape MMs' frames of reference. Perception based constructs such as these allow for deeper analysis of cognitive and organizational drivers of comprehensiveness (Meissner and Wulf, 2014). We are interested in the ways by which these managers make sense of how their activities are related to strategies (Mantere, 2005) and how comprehensiveness mediates the micro-level influence of these constructs on implementation performance.

Championing

Information availability

Whilst we stated above that merely communicating strategic priorities is limited in its ability to align individuals with expected behaviour, and hence the importance of champions, the communication of strategy relevant information is nevertheless crucial for practitioners. TMs and MMs are likely to have a different informational base from which they see the organization and its environment (Raes et al., 2011), producing potential for different interpretations. The dissemination of information allows for sensemaking so that individuals understand how the strategy relates to daily work activities, decisions they have to make, and priorities they are expected to address (Mantere, 2005; Vilà and Canales, 2008). Employees who do not have a common understanding of strategic issues create a major barrier to implementation (Bordia et al., 2004; Rapert, Velliquette and Garretson, 2002); hence information exchange between superiors and subordinates is critical to creating shared understanding (Mantere, 2005; Raes et al., 2011).

Comprehensiveness and implementation performance

MCs and implementation performance

MCs are central to strategy formation as they shape the emergence of strategy and support the implementation of deliberate strategies (Gond et al., 2012; Marginson, 2002). They are key elements of an organization's internal context which have an enabling or disabling influence on strategy formation (Mantere, 2005). Similarly to comprehensiveness, MCs have the capacity to influence alignment with performance objectives and to influence adaptiveness to changes in such objectives (Tiwana, 2010), hence helping to shed light on how strategy materializes within organizations operating within volatile environments.

TMs' expectations are communicated by the MCs in use, which direct employee attention (Floyd and Lane, 2000; Jaworski and MacInnis, 1989). Both forms influence employee behaviour and consequently the degree to which goal congruence can be achieved (Gani and Jermias, 2012). There is a strong relationship between the MCs used, strategy processes and performance (Daft and Macintosh, 1984; Jaworski, Stathakopoulos and Shanker, 1993; Marginson, 2002). Prior research into MCs suggests that in times of uncertainty there is the requirement to combine more formal controls with more interpersonal and flexible control approaches (Chenhall, 2003). MCs provide the stability necessary to meet the needs of efficiency, whilst simultaneously creating an information environment that permits MMs to envision and respond to new organizational opportunities (Gani and Jermias, 2012).

Formal controls are written, information-based mechanisms, designed to influence the probability that personnel will behave in ways that support the stated strategic objectives (Jaworski and MacInnis, 1989). In this sense, such controls are accepted as legitimate; they are well practised through repeated ‘doing’ in the past (Mantere, 2005). There are two main types of formal controls: process and output (Jaworski and MacInnis, 1989; Jaworski, Stathakopoulos and Shanker, 1993; Ouchi and Maguire, 1975).

Process (behavioural) controls are used to influence how a given job is performed and thus how the means, behaviour or activities leading to a given outcome are typically evaluated. Such control is the basis for standard operating procedures, requiring that the organization has a complete understanding of the interdependences among activities to deliver high performance (Ittner and Larcker, 1997; Jaworski, 1988). In exercising process control, TMs hold the employee responsible for following the prescribed process but not the outcome.

Output controls are used to evaluate the behaviour of individuals in terms of the results of that behaviour relative to set standards of performance. In using output control, the organization does not need to know the causal mechanisms necessary to steer employees back on course, as responsibility is delegated to the employee (Jaworski, 1988). From a SAP perspective, formal controls might be regarded as recursive approaches: planned practices which promote a unified conception of strategy via performance evaluation (Mantere, 2005).

Informal controls, on the other hand, represent control by socialization (Anderson and Oliver, 1987; Carbonnel and Rodriguez-Escudero, 2013). They are unwritten, typically worker-initiated mechanisms, designed to influence behaviour (Jaworski and MacInnis, 1989). Such controls are interactive, adaptive and organic and help manage the need for flexible responses (Ahrens and Chapman, 2004; Chenhall and Langfield-Smith, 2007; Osborn, 1998).1 They facilitate the acquisition of reliable information for formal control. Professional control is a form of such informal control, representing the prevailing social perspectives and patterns of interpersonal interactions localized within organizational sub-groups or departments with similar values (Jaworski, 1988; Ouchi, 1979). These controls are used by peers within the work group via interaction, discussion and informal assessment. Professional control can be deemed very salient in high tech organizations, as individuals value their perceived credibility or reputation more than elements such as titles or hierarchical positions (Bahrami, 1992). As a social practice based on sub-group norms, the direction of control comes from the internalization of values and mutual commitment towards some common goal where employees have a certain amount of discretion in the use of such MCs (Ahrens and Chapman, 2004; Jaworski, 1988) based on their experience and expertise (Abernethy and Stoelwinder, 1995). As SAP emphasizes the social aspect of strategizing (Whittington, 2007), professional controls are a salient agency mechanism to investigate. Such an adaptive approach to MCs places emphasis on a dynamic understanding of strategy built on individuals' interpretations of strategy through impromptu discussions between practitioners (Mantere, 2005). As such professional controls become a means for surfacing emergent strategies which is of importance in volatile environments.

Since it is acknowledged that control types are not interdependent of each other (Anthony, 1953; Jaworski, Stathakopoulos and Shanker, 1993), MCs can combine the more formal with flexible mechanisms (Ahrens and Chapman, 2004; Tiwana, 2010). Previous studies offer mixed reviews on the appropriate combination of MCs for organizations operating in volatile environments (Cravens et al., 2004; Gond et al., 2012; Jaworski, 1988; Simons, 1991). Following our argument that materialization incorporates deliberate and emergent processes, the goal here is for controls to combine synergistically to maintain stability and enable flexibility to influence the attainment of particular objectives (Jaworski, Stathakopoulos and Shanker, 1993; O'Grady, Rouse and Gunn, 2010). Hence we suggest that an appropriate balance of control types is necessary for strategy to be materialized within organizations operating in volatile environments.

We argue that in volatile environments professional control has positive implications for implementation performance, since MMs have greater flexibility and creativity in how they behave in implementing the strategy. Professional control stimulates and guides emergent strategies in response to opportunities and threats within the external environment, thus directing MMs' attention toward strategic uncertainties and to learning novel responses to changing environments (Gond et al., 2012). It plays an important part in surfacing relevant knowledge when needed and in identifying unexpected but useful courses of action in time for them to be acted upon (Osborn, 1998). Given that output controls allow MMs autonomy in the way they achieve objectives (Kownatzki et al., 2013) they provide the potential for stimulating the search for innovative ways to meet performance objectives which are arguably beneficial when uncertainty is high and changes unpredictable (McGrath, 2001).

Methodology

Quantitative studies and cross-sectional descriptive designs, as ours, are common in strategy research (Mackenzie, 2000). The empirical SAP literature, however, is strongly dominated by the use of qualitative methods (Golsorkhi et al., 2010; Vaara and Whittington, 2012). To our knowledge there are two notable published exceptions: the articles authored by Hodgkinson et al. (2006) and Healey et al. (2013).

Our quantitative study responds to Whittington's (2002) call for methodological pluralism and follows Huff, Neyer and Moslein's (2010, p. 206) suggestions ‘for expanding evidence on strategizing’ explaining that ‘Ethnographic methods have become the cornerstone of the field and will continue to be useful […]. However, methods with other strengths are also needed. […] it is particularly important to collect data that can support more generalized and more precise conclusions’ (2010, p. 206). Moreover invoking the notion of methodological fit (Edmondson and McManus, 2007) it can also be argued that the field is ‘ripe’ for quantitative studies.

Edmondson and McManus (2007) suggest that when the field is nascent qualitative methods should be used, once it is intermediate both quantitative and qualitative methods should be used, and when it is mature quantitative methods should be used. The SAP field is now over 10 years old and therefore maturing. The field has grown tremendously since 2003 and, as reviews of the field have shown (Jarzabkowski and Spee, 2009; Vaara and Whittington, 2012), SAP has produced many new insights, constructs and issues using exploratory qualitative studies. Qualitatively developed propositions should now be quantitatively researched to allow the generation of more generalizable and precise conclusions (Edmondson and McManus, 2007): hence our choice of design. We want not only to enhance our theoretical understanding of strategy formation but also to qualitatively test supported relationships.

Sample and data collection

We used a self-administered postal survey from a stratified random sample of MMs from 701 UK high tech organizations to collect our data. Survey questions explored respondents' knowledge about strategizing activities. The North American Industrial Classification System categorizes high tech firms as makers/creators of technology products, communications and/or services (Platzer, Novak and Kazmierczak, 2003). High tech organizations were chosen as they tend to have a higher new product launch rate and thus MMs in such organizations are likely to be aware of their organizations new product-market strategy, as well as current and/or on-going initiatives (Hitt et al., 2001). We drew our sample from The Marketing Managers' Yearbook (Heymer, 2005). We identified named, designated company informants who met our selection criteria as working in marketing management or related positions within high tech companies, as denoted by the Standard Industrial Classification, with more than 100 employees and a marketing budget over £100,000. Our sample and control variables are described in Table 1. We included industry variations to help provide external validity in our results. Our informants were deemed knowledgeable about the topics under study relative to product-market strategy (Zott and Amit, 2008), but we also employed measures to check respondents' knowledge about the major issues covered in the study and the extent to which the respondent believed the responses to accurately reflect the realities within the organization (Atuahene-Gima and Murray, 2004; Slater and Atuahene-Gima, 2004).

| Respondents' job titles | |

| Marketing Managers/Directors | 57% |

| Product Managers | 21% |

| Marketing Executives | 7% |

| Sales and Marketing Managers | 6% |

| Marketing Operations Managers, Brand Managers and Communications Managers | 4% |

| Tenure of respondents | |

| More than 5 years | 65% |

| Less than 2 years | 12% |

| Control variables | |

| Average firm size (measured by number of employees, to control for greater complexity in the firm's strategy making) | 250 employees |

| Average project size (measured by the number of employees with a significant influence in strategy decision making to control for interaction dynamics that affect the performance of groups) | 7 employees |

| Average project length (in terms of the length of the implementation) | 1 year |

In view of our research design, informants may have held beliefs about how comprehensiveness and performance were related and may have provided data consistent with their beliefs – hence common method variance is a potential source of measurement error (Podsakoff and Organ, 1986; Podsakoff et al., 2003). In describing our theoretical model we explicitly focus on MMs' perceptions, making self-reports the most theoretically appropriate measurement (Conway and Lance, 2010). Furthermore, retrospective accounts of past facts are purported to be more accurate than accounts of beliefs and intentions, which are more subjective and vulnerable to the effects of cognitive biases and faulty memory (Golden, 1992). In Table 2 we list the measures we took to mediate common method variance and other potential sources of error.

| Potential source of error | Measure taken to alleviate issue |

|---|---|

| Common method variance |

|

| Self-reports |

|

| Non-response bias |

We received 97 eligible responses from 150 returned surveys. Our response rate (Frankel, 1983) was 21.5% which is acceptable for studies using primary data (Slater and Atuahene-Gima, 2004).

Measures of constructs and validity

Table 3 describes the measures and their sources. It is worth noting that these items are about capturing what MMs do or what underlies their actions when strategizing (Stensaker and Falkenberg, 2007) and hence are consistent with the SAP perspective that pinpoints the need to acquire an understanding of the doing of strategy.

| Measures and sources | Description | Factor loading |

|---|---|---|

|

Implementation performance (Menon et al., 1999; Miller, Wilson and Hickson, 2004; Noble and Mokwa, 1999) Eigenvalue 5.430, α = 0.93 % of variance explained (67.876) |

This strategy is an example of effective strategy implementation | 0.894 |

| The implementation effort of this strategy is generally considered a success in this firm | 0.895 | |

| I personally think the implementation of this strategy is a success | 0.897 | |

| The implementation of the strategy is considered a success in my area | 0.843 | |

| The right kind of resources are allocated to strategy implementation efforts | 0.808 | |

| Adequate resources are allocated to strategy implementation efforts | 0.799 | |

| We effectively execute the actions detailed in the plan | 0.605 | |

| Overall our strategy is being effectively executed | 0.811 | |

|

Comprehensiveness (Bailey et al., 2000) Eigenvalue 5.626, α = 0.94 % of variance explained (70.326) |

When we formulate a strategy it is planned in detail | 0.875 |

| Our strategy is made explicit in the form of precise plans | 0.861 | |

| We have well defined planning procedures to search for solutions to strategic problems | 0.859 | |

| We have precise procedures for achieving strategic objectives | 0.845 | |

| We evaluate potential strategic options against explicit strategic objectives | 0.836 | |

| We meticulously access many alternatives against explicit strategic objectives | 0.828 | |

| We make strategic decisions based on a systematic analysis of our business environment | 0.805 | |

| We have definite and precise strategic objectives | 0.795 | |

|

Top management championing (Noble and Mokwa, 1999) Eigenvalue 6.513, α = 0.91 % of variance explained (43.418) |

I don't feel that senior management places a great deal of significance on this strategy (r) | 0.738 |

| It is clear that senior management want this strategy to be a success | 0.860 | |

| I feel this strategy is strongly supported by senior management | 0.877 | |

| Senior management doesn't seem to care much about this strategy (r) | 0.861 | |

|

Information availability (Miller, 1997) Eigenvalue 1.262, α = 0.87 % of variance explained (8.415) |

Information concerning strategy implementation becomes available well in time | 0.884 |

| I find that information is freely available for strategy implementation | 0.788 | |

| Information relating to strategy implementation is accurate | 0.769 | |

|

Professional control (Jaworski, Stathakopoulos and Krishnan, 1993) Eigenvalue 2.820, α = 0.91 % of variance explained (18.798) |

The firm encourages job related discussions between professionals (colleagues) | 0.885 |

| The firm fosters an environment where professionals respect each other's work | 0.876 | |

| Most of the professionals in my firm are familiar with each other's productivity | 0.870 | |

| Most professionals in my firm are able to provide accurate appraisals of each other's work | 0.832 | |

| The firm encourages cooperation between professionals | 0.805 | |

| The work environment encourages professionals to feel part of this firm | 0.563 | |

|

Process control (Jaworski, Stathakopoulos and Krishnan, 1993) Eigenvalue 1.525, α = 0.90 % of variance explained (10.167) |

My line manager modifies my procedures when desired results are not obtained | 0.888 |

| My line manager evaluates the procedures I use to accomplish a given task | 0.861 | |

| My line manager monitors the extent to which I follow established procedures | 0.842 | |

|

Output control (Jaworski, Stathakopoulos and Krishnan, 1993) Eigenvalue 6.6400, α = 0.90 % of variance explained (44.268) |

My line manager monitors the extent to which I obtain my performance goals | 0.850 |

| Specific performance goals are established for my job | 0.822 | |

| I receive feedback from my line manager concerning the extent to which I achieve my goals | 0.781 | |

| I receive feedback on how I accomplish my performance goals | 0.761 | |

| If my performance goals aren't met I would be required to explain why | 0.743 | |

| My pay increases are based upon how my performance compares with my goals | 0.733 |

Analysis and results

The variance inflation factors were all within an acceptable range indicating that multi-collinearity is not a problem. Table 4 contains the correlation results and descriptive statistics. Table 5 presents the mediation effect of comprehensiveness on our cognitive context constructs and implementation performance (Baron and Kenny, 1986). Our results indicate that comprehensiveness fully mediates the influence of championing on implementation performance (α = 0.09, non-significant) and partially mediates the relationship of information availability on implementation performance (α = 0.35**, p ≤ 0.01). Table 6 contains the regression results. Model 1 tests the effects of the control variables on strategy comprehensiveness. The addition of championing and information availability in model 2 added 36% (F = 11.91, p ≤ 0.01) to the explained variance in model 1. Hypothesis 1a is strongly supported (α = 0.34, p ≤ 0.01) as is Hypothesis 1b (α = 0.35, p ≤ 0.01). Our control variables were not significant predictors of comprehensiveness.

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Implementation performance | 3.56 | 1.11 | 1 | |||||||||

| 2. Comprehensiveness | 3.76 | 1.24 | 0.618** | 1 | ||||||||

| 3. Top management championing | 2.65 | 1.19 | 0.500** | 0.577** | 1 | |||||||

| 4. Information availability | 4.05 | 1.23 | 0.586** | 0.516** | 0.498** | 1 | ||||||

| 5. Professional control | 3.47 | 1.32 | 0.512** | 0.495** | 0.429** | 0.496** | 1 | |||||

| 6. Process control | 4.48 | 1.43 | 0.110** | 0.380** | 0.229** | 0.114 | 0.317** | 1 | ||||

| 7. Output control | 3.23 | 1.34 | 0.286** | 0.361** | 0.293** | 0.321** | 0.396** | 0.504** | 1 | |||

| 8. Firm size | 2.65 | 0.712 | −0.016 | −0.047 | 0.026 | 0.052 | −0.005 | −0.053 | −0.121 | 1 | ||

| 9. Project size | 0.90 | 0.44 | −0.075 | −0.242 | −0.189 | 0.098 | 0.006 | −0.117 | −0.130 | 0.185 | 1 | |

| 10. Project length | 0.04 | 0.36 | 0.020 | −0.128 | −0.055 | 0.183* | 0.073 | −0.023 | 0.068 | 0.092 | 0.232* | 1 |

- †p ≤ 0.1; *p ≤ 0.05;

- **p ≤ 0.01.

| Direct effects and indirect effects | R | R2 | R2 change | Beta |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Implementation performance on | ||||

| Top management championing | 0.64 | 0.42 | 0.26** | |

| Information availability | 0.47** | |||

| Comprehensiveness on | ||||

| Top management championing | 0.64 | 0.40 | 0.40** | |

| Information availability | 0.32** | |||

| Model 1. Implementation performance on | ||||

| Comprehensiveness | 0.64 | 0.40 | 0.37** | |

| Model 2. Implementation performance on | ||||

| Top management championing | 0.70 | 0.48 | 0.08 | 0.09 |

| Information availability | 0.35** |

- †p ≤ 0.1; *p ≤ 0.05;

- **p ≤ 0.01.

| Variables | Hypothesis | Comprehensiveness | Implementation performance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | ||

| Controls and direct effects | ||||||

| Firm size | −0.06 | −0.10 | 0.00 | −0.04 | 0.00 | |

| Project size | −0.21† | −0.12 | −0.15 | −0.03 | −0.05 | |

| Project length | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.06 | |

| Top management championing | H1a | 0.34** | ||||

| Information availability | H1b | 0.35** | ||||

| Comprehensiveness | H2 | 0.58** | 0.48** | |||

| Professional control | H3a | 0.25* | ||||

| Process control | H3b | −0.26** | ||||

| Output control | H3c | 0.18† | ||||

| R2 | 0.05 | 0.42 | 0.03 | 0.35 | 0.45 | |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.02 | 0.38 | −0.01 | 0.32 | 0.40 | |

| F | 1.59 | 11.91** | 0.81 | 11.39** | 9.51** | |

- †p ≤ 0.1; *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01.

Models 3–5 present the results for our hypotheses of the relationships between strategy comprehensiveness and MCs on implementation performance. Model 3 tests the effects of the control variables on implementation performance. Model 4 presents the results of Hypothesis 2 adding 31% of the variance explained in model 3. Hypothesis 2 is strongly supported (α = 0.58, p ≤ 0.01). In model 5 we added MCs (-). Their addition accounts for 8% of the variance explained in model 4. Hypothesis 3a is supported (α = 0.25, p ≤ 0.05), as are Hypotheses 3b (α = −0.26, p ≤ 0.01) and 3c (α = 0.18, p ≤ 0.1). Consistent with previous studies (Hopkins and Hopkins, 1997), the control variables were not significantly predictive of implementation performance.

Before discussing our results and highlighting our contributions we need to mention some of the limitations inherent in our study. First our design prohibits the establishment of any causality from a longitudinal perspective and we acknowledge that future research could address this. Second, whilst we included industry variations to enhance external validity, we did not control for firm-specific contextual determinants within the different industries. Third, our research design did not separate public and private organizations; however, it should be noted that doing so might generate different results since the reduced regulatory and reporting requirements in private companies mean that resources are freed up to allow a focus on longer term goals which might result in smoother implementation performance.

Discussion and conclusions

Through our exploration of antecedents that help strategy materialize, we have advanced understanding of some of the ‘all kinds of stuff’ (Whittington, 2007) that strategy formation involves, which is a key SAP concern (Vaara and Whittington, 2012). We have illuminated the role micro-level mechanisms play in implementation performance by linking micro-phenomenon to macro-phenomenon (a fundamental SAP agenda), and have furthered our understanding about what contributes to or inhibits the materialization of strategy in volatile environments. This is important, as SAP research is ultimately concerned with the micro-level foundations of strategy making in order to help illuminate organizational outcomes (Orlikowski, 2010). With this study we contribute both theoretically and empirically to the strategy formation literature, notably the Mintzbergian perspective, by arguing that, when considering how strategy materializes, researchers should consider MCs and comprehensiveness, which put human factor to the fore, highlight the importance of context in guiding behaviours, and allow for the examination of emergent and deliberate strategy. We present and discuss our theoretical and empirical contributions next.

There is a dearth of management studies that have directly explored the role of formal and informal MCs on implementation performance. We thus make a theoretical contribution to the strategy formation literature in our argument by highlighting their importance for understanding how strategy materializes. They are part of the organizational context within which MMs implement strategy and influence what managers do. Output and professional controls have an enabling influence on MMs and we suggest that they positively impact implementation performance. We argue that process control inhibits MMs' sense of autonomy and self-control (Ouchi, 1979). Hence such MCs relying as they do upon routinized rules and procedures may not be salient for the materialization of strategy in volatile environments.

The incorporation of professional MCs, however, allows discretion for control within the work group through patterns of interpersonal interactions and impromptu discussion (Ahrens and Chapman, 2004). It is thus adaptive to an organization's context, and specifically volatility and a source of emergence (Osborn, 1998). Output controls too impact positively on implementation. As suggested, output control is a recursive MC well suited to monitoring the deliberate strategy (Osborn, 1998), yet it affords MMs a degree of responsibility in implementing strategy, beneficial in volatile environments (McGrath, 2001).

Whilst all forms of control improve our understanding of how strategy materializes, in explicitly recognizing that professional controls are antecedents to implementation performance we contribute to the strong body of work which emphasizes strategizing as a social practice (Jarzabkowski and Balogun, 2009; Whittington, 2004). These controls are informal with values and norms of the professional group guiding behaviour (Falkenberg and Herremans, 1995). We provide new insight into the role of a social mechanism which has so far received little attention within this body of work, but which illustrates that socialized strategizing is important for the materialization of strategy.

Following this argument, we suggest that MCs should be considered a strategic tool. As its name implies, an implement is a tool, and hence any strategizing activities that are directed towards the implementation of a strategy can be conceptualized as being a strategic tool. Specifically, we propose that, as planning is well established as a strategic tool (Spee and Jarzabkowski, 2009; Wolf and Floyd, 2013) and argued to be an outcome control (Kownatzki et al., 2013), MCs should also be conceptualized as such. We propose this as they impact on implementation performance and hence firms can use these too to control how strategy materializes. This conceptualization is in line with Ashcraft, Kuhn and Cooren (2009)'s account that artifacts may have material, such as texts, and ideational, such as norms, qualities. They also explain that artifacts influence people's behaviour and attitudes in organizations. This is what MCs do. By conceptualizing control as strategy tools, the use of MCs can start to be recognized as part of wider strategizing activities (Spee and Jarzabkowski, 2009), e.g. as catalysts for new initiatives (Simons, 1991). They can start to be seen as resources that shape strategizing and that can also be manipulated to affect their outcome. Hence it can be suggested that they are critical to understand as social and political interactions in strategizing (Jarzabkowski and Balogun, 2009). They are part of what people do in strategy (Johnson, Melin and Whittington, 2003). Hence, if MCs are recognized as strategic tools rather than as management tools used to monitor individuals, they may be taken more into consideration by both scholars and practitioners since they ‘form a critical and cognitively demanding element in the practice of effective strategy workers' (Wright, Paroutis and Blettner, 2013, p. 92). The use of both formal and informal controls in organizations facing volatile environments is a means of organizing attention and therefore a powerful tool for guiding and energizing the competitive evolution of the organization (Simons, 1991).

An additional theoretical contribution to the strategy formation literature is provided through our argument that comprehensiveness represents not only formality in planning but also flexibility; to date this literature comprehensiveness has only considered it as being about formality (Forbes, 2007; Hutzschenreuter and Kleindienst, 2006; Wolf and Floyd, 2013). We have shed light on comprehensiveness as a means through which both deliberate and emergent strategy comes about. It balances the need for stability via formality of approach and flexibility through stimulating greater information research and the choice of potential strategic alternatives that come from TMs' championing and information availability. These are important aspects of MMs' cognitive context that help shape their frames of reference and create a shared understanding of strategy through the symbolic sense-giving practices between TMs and MMs (Mantere, 2005; Vilà and Canales, 2008). This is an important addition to the literature, as it provides a more nuanced understanding of comprehensiveness: by grounding comprehensiveness in Mintzberg and Water's (1985) emergent view, it becomes a more realistic and socialized rather than simply a rational process (Wolf and Floyd, 2013). Hence this also substantiates quantitatively previous qualitative studies revealing the importance of social interaction and cognition in strategizing (Jarzabkowski and Balogun, 2009; Ketokivi and Castañer, 2004; Miller, Burke and Glick, 1998; Stensaker and Falkenberg, 2007).

We also make an empirical contribution to the strategy formation literature and to the literature concerned with organizations operating in volatile environments. We do so not only by providing evidence of the positive impact of output and professional control and of comprehensiveness but also by showing that in volatile environments MCs and comprehensiveness work in tandem (see Table 5). As such, our study highlights the dynamics of the relationship between comprehensiveness and MCs for firms operating within these environments. We suggest that selected MCs and comprehensiveness reinforce each other as sources of emergence and the establishment of an operating context facilitating interaction and opportunities for discussion, and alignment of different mind-sets and practical viewpoints (Gond et al., 2012). This aids in reaching understanding and commitment and ultimately fostering positive strategy implementation behaviour. With this study, therefore, we build on the long standing debate surrounding the merits of comprehensiveness for organizations facing volatile environments (Bourgeois and Eisenhardt, 1988; Fredrickson and Mitchell, 1984; Glick, Miller and Huber, 1993; Meissner and Wulf, 2014; Miller, 2008). At the same time we underline important sources which encourage comprehensiveness under such conditions. Clearly, therefore, encouraging comprehensiveness, and employing appropriate MCs which balance formal with informal mechanisms within firms faced with environmental volatility, avoids constraining MMs to pre-specified plans and objectives in strategy formation, but allows them to identify strategic opportunities by facilitating their reaction to changing environmental circumstances supporting the exploration of new directions of evolution and increasing the likelihood of successful implementation.

To conclude, we add that by adopting a quantitative research design we respond to the call for the need for quantitative SAP research (Whittington, 2002) and that, because strategic management has both academic and managerial elements (Pettigrew, Thomas and Whittington, 2002) and because practical utility should be part of the contribution (Corley and Gioia, 2011), this study has implications for practitioners in terms of providing some guidance into the mechanisms that can be manipulated to help strategy materialize positively.

Footnotes

Biographies

Lisa Thomas is Associate Professor of Strategy at NEOMA Business School, France. She was previously Senior Lecturer in Strategy at Salford University, UK, IESEG School of Management, Paris, and Lecturer in Strategy at Cardiff Business School, Cardiff University, UK. Her research focus is on strategy implementation from a strategy process and strategy as practice perspective.

Véronique Ambrosini is a Professor of Management (Strategic Management) at Monash University, Australia. She was previously a Professor of Strategic Management at the University of Birmingham and at Cardiff University, UK. Her research is conducted essentially within the resource-based and dynamic capability view of the firm and takes a strategy as practice perspective.