Global Public Goods, Global Programs, and Global Policies: Some Initial Findings from a World Bank Evaluation

This paper was presented at the ASSA winter meetings (Washington D.C., January 2003). Papers in these sessions are not subjected to the journal's standard refereeing process.

The share of official development assistance (ODA) going to global programs has increased considerably during the past decade while overall ODA has stagnated at about $45 million annually (Ferroni and Mody, p. 19). According to Hewitt, Morrissey, and te Veldt, spending on international public goods represented 5.0% of overall ODA in 1980–82, 6.8% in 1990–92, and 8.8% in 1996–98, with the growing share occurring primarily in the environment and health areas. This growth in funding of global programs is one result of the accelerated pace of globalization and is leading to a new vocabulary in the international development assistance community related to the provision of global public goods (GPGs). Though articulated most comprehensively in Kaul, Grunberg, and Stern's volume on Global Public Goods at the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), others have also emphasized the importance of globalization and the need for an appropriate response.1 In 1996, well before Seattle, Roberto Ruggiero, then head of the World Trade Organization (WTO), described globalization as a concept that now “overwhelms all others,”2 and Charles Kindleberger, commenting on the UNDP book, described the subject as “complex but of paramount importance to a world experiencing, or approaching, multidimensional crises” (p. vi.). Inge Kaul et al. at the UNDP have now produced a follow-up volume, taking the theory of GPGs further.

The World Bank is developing its own strategic framework for involvement in global programs based on the concept of GPGs, while conceiving GPGs mainly in terms of cross-national benefits, cross-national collective action, and partnerships. The Bank has become the largest manager of trust funds for global programs with no close seconds (World Bank 2001, p. 130). It is currently involved in more than seventy global programs (compared with about fifteen 10 years ago), thirty of which are managed inside the Bank and forty elsewhere, not including about fifty regional programs and another eighty global institutional partnerships (Operations Evaluation Department, p. 13). The Bank spent about $30 million of its net administrative budget on global programs in 2001, contributed $120 million from its Development Grant Facility (DGF), and disbursed a further $500 million from Bank-administered global trust funds (Operations Evaluation Department, p. 6). These represented about 10% of the Bank's gross administrative budget and about 40% of all trust fund disbursements in 2001.

The Concept of Global Public Goods

It is important to scrutinize all three terms—global, public, and goods—in this new syntax. Public goods are distinguished from private goods by their two attributes of publicness—nonrivalry and nonexcludability. Global public goods are distinguished from national and local public goods by their reach—that is, that their public attributes spill across national boundaries. That people in many countries can consume GPGs at the same time—compared with national and local public goods, which can only be consumed by residents of a particular country or locality—has significant financing implications.

All public goods tend to be undersupplied (or public “bads” oversupplied), due to prisoners' dilemma and free riding, both of which impede coordinated provision, whether by markets, hierarchy, or collective action. The advocates of GPGs say that this is even more so for GPGs, due to the absence of a global government, and argue for a new and improved international architecture that builds on current international arrangements to increase the supply of GPGs.

Genuine GPGs include a variety of global rules that facilitate global trade, commerce, transport, and communications, as well as global public bads such as climate change, communicable diseases, financial contagion, and conflict and insecurity. But there exist few pure GPGs. Some goods, such as the Suez and Panama canals and INTELSAT, are nonrival (up to the point of congestion) but excludable, and are referred to as “club” goods. Other goods, such as ocean fisheries and other natural resources, are nonexcludable but rival and are referred to as “common pool” goods. The provision of new technologies such as vaccines and improved crop varieties of global importance are generally viewed as GPGs.3 But their adaptation and provision at the national level is a national public good, the vaccine or the seed in which the technology is embodied will in most cases be a private good, and the trade and intellectual property regimes that govern their availability will be both global and national public goods, depending on the jurisdiction. Although some have applauded the public provision of such rules of exchange for enhancing private sector investments in health and agricultural research, others have questioned the way in which such rules are evolving, leading to a tragedy of the “anti-commons,” that is, the underutilization of new technologies, due to the restrictions accompanying the granting of private intellectual property rights (Commission on Intellectual Property Rights, p. 4). Whether particular goods are public or private also tends to be contextual, depending on history, stage of development, institutions, and technological change. Richard Cooper and the World Bank (1994) cite examples of private goods that later became public goods, and vice versa.

Global Public Goods, Globalization, and Global Programs

It should therefore not be surprising that, due to the diversity of “public” and “private” goods, that there has been much confusion and debate about the concept of GPGs, about its relationship to globalization, global policies, and global programs, about getting global policies right versus investing in global programs, and about the alleged diversion of international aid funds to the provision of GPGs. There are concerns about the productivity of these GPG expenditures and about the appropriate criteria for allocating aid resources among global, regional, and national levels, as well as among competing global programs (Hewitt, Morrissey, and te Velde). These concerns led the World Bank's board and management to request its Operations Evaluation Department (OED) to conduct an independent review of the Bank's growing involvement in global programs.

Questions about the practical applicability of the concept of GPGs were confirmed in a wide-ranging consultation that OED's global evaluation team has conducted among aid officials who finance global programs, policymakers, managers, analysts, and beneficiaries of global programs. Although some equate “global” with international, others emphasize the differences between the two notions. Some consider globalization a recent development, others cite its historical antecedents. Some champion it, others denounce it. Highlighting these differences, Sholte and others have argued that the notion of de-territorialization is what distinguishes the current globalization in a historical context.4 The current globalization is associated with supra-territorial, transworld and trans-border social spaces that did not exist before. However, the contemporary rise of supra-territoriality has by no means brought an end to territorial geography. On the contrary, because the global and territorial spaces coexist and interrelate in complex ways, both the phenomenon and the current pace of globalization indeed pose complex challenges.

The rapid pace of technological change, the diminishing cost of transportation, communication, and information, the increasing flows of international capital, increased international migration, and at least the fear of the spread of disease and threats to the environment, peace, and security have all increased both the interest in and opportunities presented by this new changing territorial “virtual” space. As a result, the theory of GPGs has acquired substantial currency as a way to address these trans-border challenges as well as perceived common interests.

In a more operational, real-world context, the debate on globalization and the appropriate response to it are not simply about the concept of “globality,” since few public goods—even if they offer trans-border benefits—are truly global. More often, they are mostly national or regional public goods, and their public goods aspects are usually limited. Instead, many other issues tend to be important in ensuring that the benefits of international public goods expenditures accrue to the intended beneficiaries. Even in the case of knowledge that is often viewed as a genuine GPG, what knowledge is generated through global programs and whether it is viewed as relevant by the intended beneficiaries are important research and evaluation issues in an operational context.

OED's Evaluation of the World Bank's Involvement in Global Programs

Therefore, the OED approached its evaluation by starting with the more tangible and evaluable concept of global programs rather than the more nebulous concept of GPGs, and then it proceeded to ask, among other things, to what extent global programs were providing GPGs. More specifically, the OED narrowed its focus from the more than 200 global and regional partnerships in which the Bank is involved, to 70 partnerships that meet the following definition of a global program: those in which the partners (1) reach explicit agreements on objectives, (2) agree to establish a new (formal or informal) organization, (3) generate new products or services, and (4) contribute dedicated resources to the program. The OED team completed a portfolio review of these seventy programs as part of its Phase 1 report that was published in July 2002, and it is currently conducting in-depth case studies of twenty-seven programs in sectors ranging from agriculture, environment, health, trade, and finance to private sector development.

-

Selectivity: How are global issues identified and how does consensus emerge as to which issues require global collective action in the form of a global program?

-

Partnerships: How do partnerships get formed and who become partners in these global programs?

-

Participation: To what extent do global programs involve the active participation of stakeholders, particularly the intended beneficiaries in developing countries?

-

Governance, management, and financing: How are the programs governed, managed, and financed, including the management of fiduciary, financial, and reputational risks?

-

Monitoring and evaluation: How are the performances of global programs being monitored and their impacts being evaluated?

Finally, the OED team is assessing the performance of the World Bank in the various roles it plays in each global program—as a convener, as a financial contributor, and as a lender to developing countries—among other things, against criteria such as arm's length relationship, financial subsidiarity, and linkage to the Bank's country operations. We present only a few of the initial findings below.

Some Initial Findings

Selectivity

Global programs are prompted by a variety of factors, of which the provision of global public goods is only one.

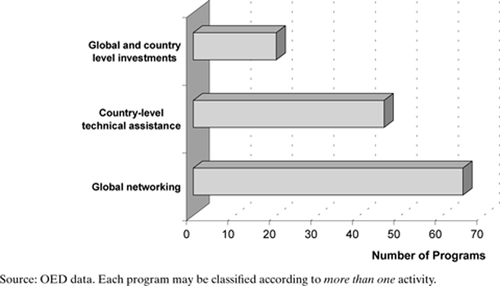

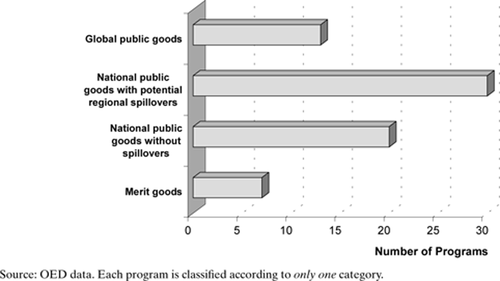

Some global programs are advocacy-oriented, established to generate information and increase awareness of the importance of and investment in addressing a problem—such as the role of UNAIDS in promoting greater investment in AIDS and of the Macroeconomic Commission on Health in promoting greater investment in health more generally. Others, such as the Global Environmental Facility, are intended to implement international agreements. Indeed, GEF is the only international vehicle for the implementation of all international agreements related to the environment. Others are mobilizing modern science to develop vaccines and generate new agricultural technologies. Still others are taking advantage of the rapid advances in communications to assemble and disseminate information. Figures 1 and 2 on the types of goods and the types of activities that global programs are providing and conducting suggest that a large number of the programs are organizing an international program to provide national-level services. This is happening in all sectors.

Classification of global programs by activities

Classification of global programs by the extent of spillovers

This finding raises two questions. First, are there scale economies in providing these services through a global or regional program rather than a national one? Certainly in the case of agricultural research, where countries are too small, lack a critical mass of scientists, and suffer from diseconomies of scale in organizing national-level research, a regional or global level of effort seems essential. Second, what other factors explain the internationalization of the provision of national services? In several cases, the global programs appear to be a result of the weak, and in some cases declining, capacity of national systems, due to underinvestment in the sector over years if not decades by both governments as well as donors. This certainly seems to be the case in agriculture, health, and environment sectors.

Partnerships and Participation

Developing countries have had little voice in defining objectives, priorities, and problem-solving approaches, thereby jeopardizing the relevance and impact of global programs.

The objectives of a number of programs are donor-driven by the constituencies in the aid agencies or aid-giving countries. Some are intended to increase the influence of specific donor countries in defining an international agenda that emphasizes, for instance, natural resource management issues, empowerment, and gender. Though important in the national context, these issues lack scalability in making an impact on a large enough area over a sustained enough period of time, given their diversity and location specificity. And the lack of a catalytic nature or rigorous methodology of these activities reduces their scope for learning transferable lessons across countries, leading them to become substitutes for national-level efforts, whether funded by donors or by national governments.

Governance and Management

Most global programs are partnerships, but the governance and management arrangements of these partnerships are often ill-defined and therefore potentially weak.

There is often a lack of shared objectives, with each partner pursuing its own objectives—for example, in the case of the Integrated Framework for Trade-Related Technical Assistance. Whereas one of the partners (the International Trade Centre) is interested in increasing trade-related technical assistance to the least developed countries, a second partner (the World Bank) is interested in mainstreaming trade-related work in the countries' development programs, and a third partner (the WTO) is interested in ensuring that the least developed countries are expanding trade in the context of the WTO-defined rules.

At the same time, there is often an insufficient definition of shared responsibility and accountability in the management and financing of global programs. Thus, some partners, such as the World Bank and the World Health Organization (WHO), tend to have an undue responsibility for the governance, management, and financing of global programs, often without utilizing the comparative advantage of the different partners, yet with high transactions costs associated with collective decision making. This often results in collective action failure with considerable inefficiencies in decision making and implementation. A partnership is neither always necessary nor always efficient in the sense of the benefits outweighing the costs.

Financing

Funding for fully justifiable global public goods programs has often been difficult to mobilize, whereas other downstream, short-term, quick-impact, small-scale programs with weaker justification for their provision at the global level are fully funded.

Research and technological generation of relevance to the poor in developing countries is a highly underfunded activity, exemplified in the health field by the so-called 80/20 phenomenon. Eighty percent of the population living in developing countries enjoys only 20% of the global health research expenditures. Yet research is a long-term, risky, and unpredictable activity with considerable problems in documenting quick results or attributing them to the program in question. Hence, such long-term, truly deserving, and much-needed global investments are underfunded whereas other programs proliferate.

Monitoring and Evaluation

Many of the programs being new, it is too early to assess their impacts. But monitoring and evaluation of the programs tend to be weak due to a lack of clear and shared objectives.

In several cases, objectives are not well defined, they are not quantifiable, and their performance is not easy to assess, particularly if a baseline is lacking, as, for example, in the role of advocacy in increasing AIDS awareness. Often information is hard to find, even on the inputs of the global programs, let alone on their outputs, outcomes, and impacts. Two notable exceptions are the extensive evaluation of the impacts of (1) the CGIAR's germplasm research on increasing productivity, incomes, and employment, and on reducing food prices in developing countries, and (2) the impacts of the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR) on the health of the poor in developing countries.

Linkages with Country Programs

Underinvestment by developing countries in complementary institutions and infrastructure to access and utilize global public goods weakens the effectiveness of global programs and pressures global programs to provide national public goods that compensate for such underinvestments.

The forthcoming review of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) reveals the political pressures on the CGIAR to invest in downstream activities popular with the constituencies of donor countries in order to show quick, short-term impacts and to compensate for declining rates of investments by developing countries and donors in the agricultural research and extension necessary for countries to access and utilize the CGIAR technologies effectively. The paper by Govindaraj and Sarna, in this same session, documents a similar phenomenon in the case of health.

Conclusion

The global program portfolio supported by the Bank could benefit from a tighter set of priorities. There is substantial underinvestment in genuine GPGs—goods that can be organized only at the international level, and with large spillovers and benefits to the poor in developing countries. There is also underinvestment in developing countries to increase their capacity to access and utilize the GPGs that are or will be provided. Equally important, industrial countries should ensure that developing countries are in a stronger position to influence the objectives of global programs of relevance to them—in short, to increase the overlap between what the industrial countries are willing to supply and what developing countries need.

But articulating the needs of the poor in developing countries is complex, because these are not the same as the demands made by developing countries. This discrepancy results from, among other things, differences between short- and long-term priorities, the tremendous competition for and shortage of resources in developing countries, and the lack of sufficient representation of the poor in developing country governments. This means that the issue of financing GPGs cannot be separated from that of financing national public goods, nor from that of the governance and management of both GPGs and national public goods. The OED review will have more to say about these issues in its Phase 2 report, due in 2003.