Food Security and Agricultural Protection in South Korea

Bureau was a visiting researcher at Iowa State University during part of this research project.

Without implicating them, the authors thank a referee and R. J. Myers for useful comments on earlier versions of the paper, and Jung-Sup Choi, Hyunok Lee, Thierry Magnac, Catherine Moreddu, and Daniel Sumner for useful discussions and help with the data. Jean-Christophe Bureau acknowledges support from the French Commissariat General du Plan and from the Center for Agricultural and Rural Development at Iowa State University.

The views presented in this paper should not be attributed to the Bank of Korea.

Abstract

South Korea has been pursuing food self-sufficiency using high tariffs and high administrative prices in key agricultural and food markets. Using a dual approach to trade and trade restrictiveness indices, we analyze the impact of these market distortions on welfare and trade volume. Then, we compute second-best distortions, which minimize the welfare cost of meeting observed levels of self-sufficiency and production. We rationalize these second-best distortions to what could be claimed as legitimate protection under a “food security” (FS) box in World Trade Organization (WTO) negotiations. FS-box protection is sensitive to changes in the definition and the extent of the FS objectives. We show that FS via production targets and reliance on imports would be more palatable to consumers and trade partners, while preserving income transfer to the farm sector.

The Republic of Korea has supported its agricultural sector at a relatively high level compared to that of other member countries of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Public intervention mainly consists of high production prices supported by government purchases, together with high tariffs that protect domestic producers from foreign competition and, implicitly, tax consumers. Trade liberalization recently took place in certain sectors, and Korea is now a major importer of oilseeds and coarse grains. However, Korea only reluctantly exposed its agricultural sector to the provisions of the Uruguay Round Agreement on Agriculture (URAA) (IATRC 1997). It has kept very high tariffs in the rice, meat, and dairy sectors; high production subsidies in most other sectors; and significant nontariff trade barriers on many commodities, including administrative barriers (import monopolies) and sanitary restrictions (IATRC 1994, Thornsbury et al.).

Exporting countries have stressed that Korean farm policy imposes high food costs on consumers and increases the cost of labor for its manufacturing sector. By artificially maintaining resources in agriculture, Korean agricultural policy allegedly slows the growth rate of the entire domestic economy (Diao et al.). Other World Trade Organization (WTO) member countries complain that Korea, while benefiting from global manufacturing export opportunities, imposes considerable obstacles to other countries' exports of food products.

The Korean government motivates its agricultural policy by food security (FS) reasons. In particular, it stresses the need for ensuring an adequate supply of food in all market conditions. It motivates its resistance to eliminating farm subsidies by the fact that food security goes beyond a multilateral trade issue.

FS is not the only motivation for Korea's agricultural policy, which has been criticized by Korean and other Southeast Asian economists (Im; Kako; Moon and Kang; Sumner, Lee, and Hallstrom; Vincent and Lee). High agricultural prices are partly motivated by political economy concerns. One objective of East Asian countries agricultural policy is to transfer income from progressively urbanized consumers to rural areas, to offset the consequences of a rapid industrialization and urbanization (Anderson and Hayami, Anderson). One might argue that raising farm incomes and land values, reducing the pace of rural-urban migration and alleviating possible externalities (e.g., congestion of infrastructures) through an implicit taxation of food consumption meet some public finance objectives because rice consumption represents a large and inelastic tax base. However, because the WTO does not recognize political economy as a legitimate reason for subsidizing agriculture, Korea stresses food security motives to justify its agricultural policy.1 Even though this stated objective is likely to hide other motives, there is evidence that the Korean population is anxious about the supply of food in the future (Kako).

Korea defines FS as a perplexing joint reliance on trade, domestic production, and self-sufficiency (WTO 2000a,b; 2001b). Despite some trade concessions under the URAA, Korea has nevertheless openly pursued food self-sufficiency as the desirable way to achieve the stated objective of FS (Sumner, Kako). FS based on self-sufficiency is a recurrent theme among developing members of the WTO. Less dependence from foreign suppliers is implicit in India's proposal for a “FS” box (WTO 2001a). Korea makes a strong case that Net Food Importing Developing Countries (NFIDCs) should be able to support the domestic production of staple crops and argues that such measures should be exempted from reduction commitments, on the grounds of FS (WTO 2001b). This leading stance echoes developing countries' proposals for “FS” and “development” boxes, which would legitimize larger support to domestic production and trade barriers. Recent debates under the auspices of the World Bank (2001) show a large coalition of sympathizers with Korea's position on FS. Free trade, it is argued, is not a guarantee of reliable access to cheap food under all conditions.2

However, self-sufficiency objectives are detrimental to (poor) consumers because of high food prices, and alternative policies, such as production subsidies, are a more targeted way to achieve FS objectives. Korea and India's promotion of self-sufficiency, which penalizes consumers, seems inconsistent with their endorsement of FS as “access to food for all,” proposed during the World Food Summit of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

Our article contributes to the agricultural trade policy debate by providing a rigorous assessment of current agricultural policies in South Korea and, more generally, of FS strategies promoted by many developing economies. In a first step, we abstract from other objectives or concerns motivating the present agricultural policy in Korea. We evaluate the stated policy objectives, that is, FS, from an economic point of view. The first contribution of our paper is to estimate the welfare costs and trade implications of Korean agricultural policy, using a multimarket dual approach to trade based on Anderson and Neary (1996). We consider major policy instruments such as tariffs, price support, input subsidies, and consumption taxes. A comparison of these costs since 1979 makes it possible to assess how the policy changes that took place in the 1990s translate into welfare.

Second, Korea is a member of a multilateral trading system based on the most-favored-nation clause. The latter implies some import volume expansion as all member countries integrate and expect to gain access to each other's markets as soon as a single member country obtains some trade concession. We measure the degree of restriction, expressed in volume of trade that is generated by Korean agricultural policy, using the “mercantilist” indicator of trade restrictiveness (Anderson and Neary 2000). This index provides a metric of foregone trade opportunities by other WTO members.

Finally, we estimate how Korea could rationalize its policy instruments for several objectives (self-sufficiency, then production/income transfer). We begin with self-sufficiency in each of the staple crops and meat, and present the structure of second-best consumption taxes and production subsidies, together with their welfare and trade impacts. We then look at FS attained under joint reliance on commodity imports and production targets for various sets of commodities. Because production targets induce income transfer to producers, we provide an evaluation of these implied income-transfers. Transfers are motivated by the domestic politics of rapid industrialization to buffer the adjustment cost of resources flowing out of the rural sector and to mitigate income differentials between rural and urban sectors. We show the sensitivity of the level and nature of protection to the commodity coverage of the target through cross-price effects in production and consumption. We conclude the targeting section by drawing implications on strategic considerations for trade negotiations regarding support levels under the development or FS box.

The policy recommendation punch line of our paper applies to all members of the WTO who, for genuine reasons or for income transfer motives, endorse or contemplate FS objectives, such as the EU policy debate to increase EU self-sufficiency in proteins. These countries should advocate deficiency payments rather than trade barriers for their agricultural production and open their borders simultaneously. This strategy is much less antagonizing than self-sufficiency for trade partners and much more beneficial to consumers and small producers who are net buyers of the targeted commodities. If one considers that FS is mainly a pretense for domestic income transfers, production subsidies are a major step in the right direction toward better-targeted distortions. Policy rents to farmers would be essentially unaffected relative to the current situation, making it possible to satisfy domestic political constraints.3

The Analytical Framework

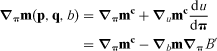

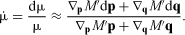

We use a multimarket model of Korean agriculture and food markets embedded in a dual approach to trade to estimate the supply and demand response to government intervention and the subsequent welfare effects. Following Anderson and Neary (1996, 2000), these distorted markets are treated as being separable from the rest of the economy. The set of policy instruments that is considered here affects output prices, consumption prices, and input prices. Tariffs and government purchases translate into producer and consumer prices higher than the border price. Input subsidies and direct payments are modeled by lower input prices that are specific to agriculture (fertilizer, irrigation, and credit subsidies). Consumption subsidies are modeled by lower consumer prices. We cover rice, wheat, barley, corn, soybean, dairy, beef, pork, and poultry. Details on the policy instruments and information on the data are provided in Beghin, Bureau, and Park.

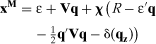

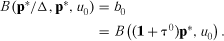

(1)

(1) (2)

(2)The properties of this partial demand system are presented in LaFrance et al. It is particularly attractive because of the possibility of calibrating the parameters using prior information. It is also rather flexible, due to the quadratic terms in prices, is consistent with the assumption of nonhomothetic conditional preferences for agricultural goods, and there are no restrictions on individual income coefficients. In addition, the expenditure function (2) is the only way to derive demands linear in income and quadratic in price consistent with weak integrability (LaFrance et al.) The elements of the n-vectors ɛ and χ in equation (1), together with the elements of the n × n matrix V, are calibrated using the procedure described in Beghin, Bureau, and Park. The calibration imposes homogeneity of degree one in prices for e and symmetry of the Hessian of e. Concavity is verified locally.

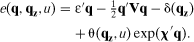

(3)

(3) (4)

(4) (5)

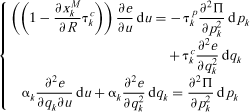

(5)The BoT function includes a general equilibrium concept. Expenditure and revenue functions characterize the private sector structure of supply and demand of the distorted sectors analyzed in the economy. However, because of the tax revenue raised by distortions, both government and private behavior are summarized by B(p, q, u), where we omit the constant elements (p*, pz, qz, γ, β). The BoT function represents the external budget constraint and is equal to the net transfer required to reach a given level of aggregate domestic welfare, u, for a given set of domestic prices. Net government revenue from agricultural and food distortions is equal to [(q − p*)′x(q, u) − (p −p*)′y(p)], where the fixed endowments are ignored to simplify notation. Consumption subsidies are captured by (q − p*) negative, the cost of tariffs and taxes to consumers by (q − p*), and the producer prices, including support and subsidies, by (p − p*).

The gradients of partial derivatives of the BoT function with respect to domestic prices (p, q) preceded by a minus sign, −∇pB and −∇qB, are the vectors of marginal welfare costs of domestic price distortions in production and in consumption, respectively. As dp and dq represent the producer and consumer price distortions, the total deadweight loss from these distortions is equal to minus the change in the foreign exchange to support u, or minus (∇pB′dp + ∇qB′dq). This is the additional foreign exchange required to compensate for a change in distorted prices (dp, dq) and to maintain the initial welfare level. Gradients ∇pB and ∇qB are derived from totally differentiating B, and can be parameterized and estimated using the calibrated food demand and supply responses as explained in Beghin, Bureau, and Park.

Welfare Costs of Korean Agricultural Policy

The producer support estimate (PSE), measured by the OECD and expressed as a percentage of the value of production, reaches 73% in Korea compared to an OECD average of 34% in 2000. The Korean government provides a few direct payments and some input subsidies (fertilizers and interest subsidies). The main policy instruments are transfers from consumers, which account for 95% of the support to farmers (OECD 2001). Many consider such forms of public intervention most distortionary and believe that they impose welfare costs on the society as a whole.

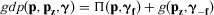

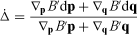

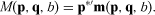

(6)

(6) (7)

(7) (8)

(8) . That is, the change in the TRI deflator is a weighted average of the proportional changes in domestic prices. The weights are the shares of marginal deadweight loss due to each policy-induced price variation. The numerator of equation (8) measures the deadweight loss of the distortion changes and corresponds to the change in compensation measures (EV or CV) induced by dp and dq, or the change in the money metric utility for the same dp, dq up to normalization by the shadow price of foreign exchange (Anderson and Martin). Table 1 provides the deadweight loss of the agricultural policy based on estimates of the components of ∇pB and ∇qB. When comparing the observed (distorted) situation 0 and the situation 1 without public intervention (at the vector p* of free trade prices without input and consumption subsidies), it is possible to calculate the different components of the numerator of equation (8). The figures shown in table 1 are in billion won at 1995 prices.

. That is, the change in the TRI deflator is a weighted average of the proportional changes in domestic prices. The weights are the shares of marginal deadweight loss due to each policy-induced price variation. The numerator of equation (8) measures the deadweight loss of the distortion changes and corresponds to the change in compensation measures (EV or CV) induced by dp and dq, or the change in the money metric utility for the same dp, dq up to normalization by the shadow price of foreign exchange (Anderson and Martin). Table 1 provides the deadweight loss of the agricultural policy based on estimates of the components of ∇pB and ∇qB. When comparing the observed (distorted) situation 0 and the situation 1 without public intervention (at the vector p* of free trade prices without input and consumption subsidies), it is possible to calculate the different components of the numerator of equation (8). The figures shown in table 1 are in billion won at 1995 prices.| Period (3-Year Average) | Increase in Agricultural Revenue | Tariff and Tax Revenuesa | Deadweight Loss Consumption | Deadweight Loss Production | Deadweight Loss Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979–81 | 6,640 | 1,762 | 1,557 | 1,553 | 3,111 |

| 1990–92 | 10,982 | 1,532 | 3,015 | 3,650 | 6,665 |

| 1998–2000 | 10,571 | 1,228 | 2,430 | 3,722 | 6,152 |

| Cumulative | |||||

| 1979–2000 | 218,595 | 26,258 | 49,976 | 69,277 | 119,254 |

- a These revenues include rents and revenues under licenses and quotas schemes.

The results provided in table 1 show how costly the social transfers induced by Korean agricultural policy are in terms of welfare. The deadweight loss associated to the transfer of 10 wons to farmers amounts to roughly 5.8 wons. This is mainly caused by the particular policy instruments fully coupled to production and taxing consumers. High tariffs and administrative prices reflect the Korean preference for self-sufficiency objectives, regardless of the cost to consumers in sectors such as rice, pork, or poultry.

(9)

(9)| Period (3-Year Average) | dΔ/Δ | Uniform Unit Distortion τ0 | Marginal Welfare Weighted Percentage Distortion on Consumption Prices | Consumption Weighted Distortion on Consumer Prices (% Actual Value) Output Prices | Marginal Welfare Weighted Percentage Distortion on Output Prices | Production Weighted Distortion on Output Prices |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979–81 | 0.58 | 1.39 | 0.59 | 0.55 | 0.58 | 0.58 |

| 1990–92 | 0.74 | 2.87 | 0.73 | 0.69 | 0.75 | 0.75 |

| 1998–2000 | 0.67 | 2.15 | 0.67 | 0.54 | 0.68 | 0.66 |

Scalar τ0 would lead to the present welfare if the reference prices were increased by this amount (i.e., if all the components of p*, the vector of netput world prices, were increased by a factor τ0p*). Scalar [∇qB0′(p* − q0)/∇qB0′q0] is the weighted sum of the unit distortion of consumption prices; the weights are the normalized deadweight loss associated with the unit distortion on a particular good. The comparison of this indicator (column 4 in table 2) with the sum of each consumption distortion weighted by the consumption of each good n (column 5) shows that the use of the marginal deadweight loss on consumption as a weight results in a larger overall index. The deadweight loss weighted average of the production distortions, [∇pB0′(p* − p0)/∇pB0′p0] (column 6 of table 2), is only slightly larger than the average distortion weighted by the share in production (column 7).

The Effect of Korean Agricultural Policy on Each Agricultural Sector

The relative impact of the various policies can be seen by simulating the effect of the whole set of taxes and subsidies on a particular commodity. This requires taking into account the specific measures for each input, such as irrigation subsidies, capital grants, subsidies for fertilizer use, etc. These inputs were allocated to each production using annual input/output coefficients (see Beghin, Bureau, and Park), and a reference input price was constructed for each commodity by allocating a detailed set of subsidies to the various agricultural productions based on the allocation used by the OECD for the calculation of PSEs.

The deadweight loss in consumption corresponding to commodity i is estimated by the scalar expression ∇qB0′(p*i − q0), where the elements of p*i are the reference price in the case of commodity i and the commodity-specific inputs and are the observed prices q0 in other cases. A similar computation is made for estimating the deadweight loss on the production side. The sum of the two components provides the total welfare effect associated with the government intervention on commodity i, which includes the market price support, the output enhancing subsidies, and the subsidies to the input used in the production of i (table 3, row 5). The contribution of the commodity-specific policy to the overall welfare is expressed as a percentage (table 3, row 6).

| Rice | Wheat | Barley | Corn | Soya | Dairy | Beef | Pork | Poultry | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value of output at domestic price | 8,474 | 6 | 189 | − | 251 | 1,050 | 1,883 | 1,966 | 619 | 14,438 |

| Value of output at reference prices | 1,957 | 5 | 41 | − | 35 | 328 | 739 | 1,332 | 503 | 4,940 |

| Consumption at domestic prices | 8,140 | 631 | 215 | 1,593 | 665 | 1,215 | 3,132 | 2,009 | 693 | 18,293 |

| Consumption at reference prices | 1,935 | 629 | 73 | 1,585 | 444 | 388 | 1,197 | 1,385 | 575 | 8,211 |

| Product-related deadweight loss (consumption; production) | 3,569 | −0.3 | 59 | 0 | 80 | 726 | 1,422 | 466 | 147 | 6,152 |

| (948) | (−0.3) | (57) | (0) | (26) | (325) | (927) | (144) | (3) | (2,430) | |

| (2,680) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (55) | (401) | (516) | (322) | (144) | (3,722) | |

| Contribution to total welfare costs | 55% | 0% | 1% | 0% | 1% | 11% | 22% | 7% | 2% | − |

| Income transfers to producersa | 7,151 | 0 | 161 | − | 229 | 793 | 1,269 | 793 | 173 | 10,571 |

| Transfer efficiencyb | 67% | − | 73% | − | 74% | 52% | 47% | 63% | 54% | 63% |

| Direct welfare effect | 2,708 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 81 | 586 | 1,348 | 378 | 44 | − |

| Cross-commodity welfare effect | −27 | −0.2 | −48 | 0 | −16 | 2 | −96 | −98 | −21 | − |

| Input welfare effect | 888 | − | 7 | − | 15 | 138 | 190 | 193 | 124 | − |

- a Includes input subsidies.

- b Defined as (transfers/(transfers + deadweight loss)).

The effect of the policy on the revenue of agricultural producers can be derived from the agricultural component of the GDP function. The gradient of π with respect to distorted prices, ∇pπ, gives the amount of income transfer resulting from an increase in output (decrease in input) prices. By Hotelling's lemma, the gradient is the netput vector. That is, the income transfer effect of the agricultural policy is measured by ∇pπ′(p − p*). A similar approach is used for estimating the income transfer effect of the agricultural policy on a commodity-specific basis. The efficiency of the agricultural policy, defined as the overall cost to the society of transferring income to producers, can be estimated by the deadweight loss (on both the consumption and production sides) associated with one unit of the extra producer income resulting from the policy. It therefore is defined as one plus the ratio of the income transfer effect (∇pπ′dp) to the welfare effect (∇pB′dp + ∇qB′dq) and is provided in Table 3, row 6, while estimates of income transfer are shown in row 7.

Rice growers get the largest transfer, followed by beef, pork, and milk producers. Rice policy has the highest contribution to foregone welfare, followed by beef, dairy, and pork. Beef has the lowest efficiency of transfer, at around 47%. The effect of government intervention on a particular product has implications in terms of substitution on both the production and consumption of other products when prices are influenced. The deadweight loss generated by a commodity-specific policy can be decomposed in terms of an own-price effect, a cross-price effect, and an input effect that measure the impact of the public policy (both on output and input through prices subsidies) on input use. Input distortions induce the largest welfare losses in rice production and then in pork and beef sectors (row 11). However, deadweight losses induced by input subsidies are nearly negligible in all other sectors, except for dairy, and poultry.

Trade Impacts of Korean Agricultural Policy and Mercantilism

As a member of the WTO, Korea had to convert quantitative restrictions on imports into bound tariffs, reduce these tariffs over an implementation period, open its market to imports under the minimum access provisions, and reduce the most trade-distorting forms of domestic support in 1994. However, Korea applied the Uruguay Round provisions so that it could protect its producers from foreign competition in key sectors (IATRC 1997). For example, Korea postponed the tariffication of rice for 10 years and negotiated an obligation to import only 4% of its consumption by 2004. In most of the staple foods, Korea has also kept import restrictions under domestic special rules. Prohibitive tariffs and administrative barriers still restrict imports of many agricultural goods to Korea (IATRC 1994). Self-sufficiency remains a policy objective (see table 4), particularly in the rice sector, because of the cultural content of this good and because of the possible reunification with North Korea, which has been experiencing dramatic shortages of rice, making this issue particularly sensitive.

| Rice | Wheat | Barley | Corn | Soybean | Milk | Beef | Pork | Poultry | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Production (103 tons) 1998–2000 | 5,217 | 4 | 271 | 0 | 128 | 2,186 | 327 | 911 | 346 |

| Consumption (103 tons) 1998–2000 | 5,148 | 3,113 | 469 | 9,438 | 1,667 | 2,595 | 547 | 959 | 401 |

| Net imports in% consumption 1979–81 | 19% | 97% | 21% | 100% | 66% | −0.1% | 19% | 14% | 0% |

| Net imports in% consumption 1990–92 | 0% | 99% | 15% | 100% | 85% | 6% | 53% | 0% | 9% |

| Net imports in% consumption 1998–2000 | −1% | 99% | 42% | 100% | 92% | 16% | 40% | 5% | 14% |

From the point of view of the other countries involved in the trade negotiations, the variable of interest is the volume of imports and exports of the given country, rather than its welfare. This motivates an evaluation of the restrictiveness of trade policy using trade volume as the reference standard rather than the utility of the representative consumer (Salvatici, Carter, and Sumner). Anderson and Neary (2000) have proposed the mercantilistic trade restrictiveness index (MTRI), which relies on the idea of finding a uniform tariff that yields the same trade volume as the original tariff structure. The definition of the MTRI shares the basic BoT framework of the TRI. It provides a metric of foregone trading opportunities induced by a set of distortions, while holding constant the balance of trade function but not utility.

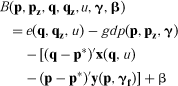

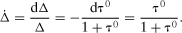

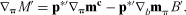

(10)

(10) (11)

(11) (12)

(12) (13)

(13) (14)

(14) (15)

(15)Using the vector of prices in the absence of distortion as the reference situation 1, and the observed prices as situation 0, the MTRI change is estimated using the expression of the demand system (2) and the sectoral GDP function (3) to retrieve the derivatives of the import demand functions (13). Table 5 provides the results. The change in the MTRI in equation (15) is a weighted sum of the proportional changes in consumption and production prices between the observed situation and the situation in the absence of public intervention. The weights are the marginal import shares of each price change.

| Period (3-Year Average) | Volume of Trade Restriction (Billion 1995 Wons) | dμ/μ | Uniform Tariff | Trade Weighted Percentage Distortion on Consumption Prices | Marginal Trade Weighted Distortion on Consumption Prices | Trade Weighted Percentage Distortion on Production Prices | Marginal Trade Weighted Distortion on Production Prices |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979–81 | 2,138 | 0.50 | 1.03 | −0.44 | −0.47 | −0.44 | −0.55 |

| 1990–92 | 2,120 | 0.51 | 1.07 | −0.45 | −0.47 | −0.57 | −0.58 |

| 1998–2000 | 2,273 | 0.39 | 0.66 | −0.27 | −0.33 | −0.45 | −0.49 |

- Note: The unit distortion is measured as (q*n − qn)/qn for consumption prices and as (p*n − pn)/pn for production prices.

The uniform tariff equivalent has decreased dramatically during the 1990s. Recall that this is the tariff that should be applied to all goods under consideration (i.e., the list of the agricultural goods covered by the OECD PSEs) as this would give the actual level of imports in these goods. The decline by one-third of this indicator between 1990–92 and 1998–2000 is mainly a result of the surge in imports of corn, wheat, and soybeans at relatively low tariffs, and an increase in the imports of beef (see table 4).

Table 5 shows that weighting individual tariffs (or, more exactly, their impact on both production and consumption prices) by the marginal trade impacts, as expressed by the MTRI, leads to higher measures of trade restrictiveness than those found using standard import-weighted average distortion.

Agricultural Policy in a Second-Best Framework

The special session of the WTO Committee on Agriculture was established for trade negotiations on agriculture during the years 2000 and 2001. Proposals made during the session show that many developing and food-importing countries share Korea's concerns about food dependency and possible prices hikes, leading to difficulties in financing normal levels of commercial imports.8 Most of them are also dissatisfied in the lack of practical effect of the 1994 WTO decision that accompanied the URAA (WTO 1994). The “Decision” was supposed to address their concerns about FS.9

We saw in two previous sections that Korean food policy has costly welfare effects and frustrates mercantilist aspirations of trade partners by restricting agricultural trade. In this section, we take FS as a stated premise and investigate second-best distortion structures for several definitions of FS, including self-sufficiency.

Tax Structure for Self-Sufficiency Targets

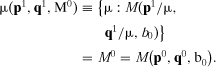

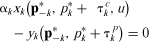

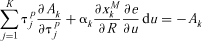

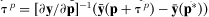

First, consider Korea's negotiating claim that WTO commitments should allow it to pursue desired FS and rural development policies, by setting an objective of a given degree of self-sufficiency in the grain sector, in the meat sector, and for a set of commodities that Korea actually produces (meat, grains, dairy). Within a second-best framework, it is possible to optimize the tax structure for achieving a given level of self-sufficiency α = (α1,…, αk,…, αK) for αkxk = yk, with the subscript referring to commodity k and with 0 ≤ αk ≤ 1, for all k = 1,…, K and K ≤ n. From the targeting principle in a small economy (Bhagwati, Panagariya, and Srinivasan; Vousden), the optimum second-best distortion structure calls for a production subsidy and a consumption tax that is equal to the α-share of the production subsidy. In addition, input subsidies are inferior to output subsidies and should not be used; that is, marginal rates of technical substitution should be left undistorted (Bhagwati, Panagariya, and Srinivasan).

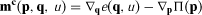

(16)

(16) (17)

(17) (18)

(18) , for targeted self-sufficiency levels αk and αj for commodity k and j. The second-best distortion reduces the excess demand (over the target) and minimizes welfare losses relative to a free trade situation, as expressed by the following equations:

, for targeted self-sufficiency levels αk and αj for commodity k and j. The second-best distortion reduces the excess demand (over the target) and minimizes welfare losses relative to a free trade situation, as expressed by the following equations:

(19)

(19) (20)

(20)In a first set of simulations, we define the second-best tax structure under the constraint of achieving the historical level of self-sufficiency over the 1998–2000 period. Simulations were conducted in two ways: imposing the observed levels of self-sufficiency for the whole set of commodities, and on a commodity by commodity basis.

Table 6 shows that the actual structure of taxes and subsidies is close to the one recommended for maximizing welfare under the constraint of the existing rate of self-sufficiency. Columns 3 and 4 of table 6 show that the ratio of the actual tax on consumption and subsidy of production is close to satisfying condition τcn = αnτcn. This is particularly the case for soybeans, a commodity whose production is supported at very high levels, but for which consumers face relatively few taxes. This suggests that, if one focuses on a self-sufficiency objective, relatively little can be gained from a reform of the tax structure under these constraints, except for the input subsidies distorting marginal rates of substitution in production. The gains from such a minor tax reform would be limited to 1,540 billion wons at 1995 prices.

| Actual Production Support (Ad Valorem Equivalent) | Actual Consumption Tax | Ratio Production/Consumption Tax | Historical Rate of Self Sufficiency | Second-Best Production Support | Second-Best Consumption Support | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice | 360% | 352% | 0.96 | 1.02a | 342% | 342% |

| Wheat | − | 0% | − | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Barley | 377% | 215% | 0.55 | 0.58 | 366% | 214% |

| Corn | − | 1% | – | 0 | 0 | |

| Soybean | 688% | 54% | 0.08 | 0.08 | 696% | 52% |

| Dairy | 222% | 215% | 0.96 | 0.85 | 238% | 200% |

| Beef | 172% | 167% | 0.94 | 0.60 | 233% | 129% |

| Pork | 52% | 48% | 0.83 | 0.95 | 51% | 47% |

| Poultry | 26% | 23% | 1 | 0.87 | 25% | 20% |

- a We constrain α = 1 for rice.

Self-sufficiency targets mean restricting demand by imposing high prices to consumers, which can lead to the absurd situation where a country insulates itself from the vicissitudes of world markets by starving its consumers. Consider the hypothetical case in which Korea would decide to become self-sufficient in proteins. In spite of a very high level of subsidies (equivalent to paying producers more than six times the world prices), Korean production of soybeans covers less than 10% of actual consumption. Simulations with the above model show that any self-sufficiency target could only be achieved by choking demand, where very high consumption taxes would restrict the use of soybeans to a level that would be close to actual production. In Korea, self-sufficiency in pork and poultry production is achieved only by importing large quantities of soybeans and corn, which is less absurd than producing the feed domestically, but still less effective than importing meat in a land-scarce country. These commodities face a relatively low tariff, while tariffs on meat are prohibitive. On this basis, self-sufficiency can hardly be defended on national security grounds: corn is supplied mainly by a single country, and the world market for soybeans has experienced some shortages in the past. This suggests that Korean self-sufficiency objectives in these sectors merely reflect simple tariff escalation and effective protection of meat products and income transfer to these sectors.

Finally, although we do not address this point formally, self-sufficiency penalizes poor consumers the most because it imposes a large expenditure share for food on them; this policy hardly qualifies under the objective to “provide food access to all.”

Tax Structure Supporting Production Targets for Food Security

A reasonable alternative would be to set production levels as targets in staple foods and rely on imports for additional sourcing of food items. Low or no tariffs on the consumer side would result in a higher demand, and the self-sufficiency ratio would decrease dramatically. However, domestic production would be maintained and would represent some insurance against world market uncertainty. The effect of this policy on domestic supply “security” would be the same as that of self-sufficiency policy, without distorting consumption decisions. In addition, this policy would achieve a similar income transfer for the targeted commodity, alleviating domestic political constraints.

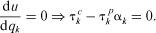

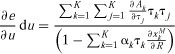

Setting the constraint of achieving historical production levels leads to set output subsidies but no consumption tax. The corresponding level of output subsidy on a subset of targeted commodities k = 1,…, K can be found by solving the program , where

, where is the level of production target for commodity k.10 The elements of τ corresponding to nontargeted commodities are equal to zero. The matrix ∂y/∂p is K × K. Simulations show that this objective leads to production subsidies comparable to the present situation, which is not surprising given the limited production impact of Korean input subsidies. In our welfare calculation we include the social cost of public funds that are necessary to pay the subsidies to the farm sector. We use the most recent available estimate of such cost for Korea, which is set to 1.1 (Dalsgaard). The cost of public funds provides a more accurate measure of welfare gains of targeting because it accounts for the social cost of raising taxes elsewhere in the economy.

is the level of production target for commodity k.10 The elements of τ corresponding to nontargeted commodities are equal to zero. The matrix ∂y/∂p is K × K. Simulations show that this objective leads to production subsidies comparable to the present situation, which is not surprising given the limited production impact of Korean input subsidies. In our welfare calculation we include the social cost of public funds that are necessary to pay the subsidies to the farm sector. We use the most recent available estimate of such cost for Korea, which is set to 1.1 (Dalsgaard). The cost of public funds provides a more accurate measure of welfare gains of targeting because it accounts for the social cost of raising taxes elsewhere in the economy.

Table 7 compares the deadweight loss (EV from free trade) in the actual situation (column 1). It also shows the trade implications of the alternative approaches to FS, which are full self-sufficiency (columns 3–5), historical levels of self-sufficiency as a target (columns 6–8), and historical production levels as a target, as resulting from a policy based on deficiency payments and no tariffs (columns 9–11). The third row of table 7 gives the value of imports of all commodities at world prices under four situations. The fourth row provides an indicator of the trade restriction caused by the corresponding tax structure, as measured by the numerator of the MTRI. Finally, row 5 provides the uniform MTRI tariff, that is, the tariff that should be imposed on all prices of tradable commodities in order to lead to the volume of trade at a world price that corresponds to a given tax structure.

| Full Self-Sufficiency Target (α = 1) on Subsets of Goods | Historical Self-Sufficiency Target on Subsets of Goods | Production Target, Historical Levels | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual Situation | Staple Grains Only | Meat Only | Grains, Meat, Milk | Staple Grains Only | Meat Only | Grains, Meat, Milk | Staple Grains Only | Meat Only | Grains, Meat, Milk | |

| Deadweight loss EVa | 6,152 | 2,725 | 4,001 | 9,730 | 2,540 | 1,444 | 4,614 | 2,371 | 663 | 3,455 |

| Value of imports at world prices | 3,275 | 4,843 | 3,702 | 2,270 | 4,842 | 4,357 | 3,381 | 5,044 | 5,065 | 4,431 |

| Trade restriction impact | 2,272 | 694 | 1,835 | 3,310 | 690 | 1,164 | 2,164 | 515 | 485 | 1,132 |

| Uniform equivalent tariff (percent) | 66 | 19 | 56 | 98 | 19 | 35 | 63 | 14 | 14 | 32 |

- a Relative to absence of public intervention.

Besides the welfare aspects, setting production targets rather than self-sufficiency targets represents a more palatable situation for mercantilist partners within the WTO and should facilitate the negotiation of large deficiency payments. This policy, which has been used in the main U.S. programs for years, makes it possible to avoid the present deadweight losses on the consumption side. This generates extra Korean imports and a loss of limited tariff revenue that can no longer be redistributed to consumers. However, the decrease in food costs for consumers, as well as the increase in consumption, results in significant welfare gains, more than sufficient to pay for the farm program as we include the cost of public funds in our welfare analysis.

Targeted deficiency payments in the staple grains sector (rice and barley) that achieve historical production levels, while removing tariffs on imports, would result in a significant welfare improvement (the deadweight loss would be reduced by 61% compared to the actual situation, to 2,371 billion wons at 1995 prices). It would also result in a significant expansion of market opportunities. A synthetic indicator of these market opportunities, the MTRI uniform tariff equivalent would fall from 66% to 14%, and the volume of trade foregone would fall from 2,272 billion wons to 515 billion at 1995 prices.

As a final note, we undertook a sensitivity analysis, which is reported in Beghin, Bureau, and Park. The simulations consider a 50% decrease and a doubling of the elasticities of the model, separately for supply, demand, and then jointly. The TRI and MTRI values are not sensitive to changes in elasticities. However and as expected, net welfare effects are more sensitive to changes in prices elasticities. A doubling of demand elasticities increases welfare losses by 40%, whereas a doubling of elasticities of supply increase welfare losses by 60%. The doubling of all elasticities is nearly additive, doubling the welfare losses.

Conclusions

Despite partial trade liberalization under the URAA, South Korea has been pursuing a policy of food self-sufficiency using trade restrictions and administrative prices in key agricultural and food markets, while following production targets with partial trade opening in lesser markets. These measures are part of a stated policy of food security, or FS. We analyzed the impact of these market distortions on welfare and trade volume and computed second-best distortions, which minimize the welfare cost of observed self-sufficiency and production objectives. We also computed second-best distortions for FS relying on domestic production and imports for all products. We rationalized these second-best distortions as what could be claimed as legitimate protection under an “FS” box in the new round of WTO negotiations.

Because Korea uses policy instruments that involve large production distortions and that impose high prices to consumers, we find that the present policies result in considerable welfare losses. The efficiency of transfers to producers is poor; each won transferred to farmers costs consumers and taxpayers roughly 1.6 won, and the objectives of self-sufficiency are obtained through a significant contraction of demand and high prices that are unlikely to make food access easier for the less-favored consumers.

The observed system of taxes and subsidies is nearly optimal to achieve self-sufficiency. Nevertheless, similar objectives of FS could be achieved through production targets and open borders without the actual (considerable) welfare losses. The product target is nearly equivalent to an income transfer target and can be legitimized on either food security or political economy grounds. While the administration of programs such as deficiency payments might be difficult in some developing countries, which lack administration capacities and a large taxpayer basis, it is unlikely to impose more of an administrative burden than current policy, characterized by a high degree of state intervention.

There is growing pressure for consideration of an FS box in a future WTO agreement and a growing recognition from developed countries that some of the NFIDCs concerns in this area are legitimate. However, genuine concerns for FS should not be used as a justification for what is actually effective protection. From this point of view, the present Korean policy in the meat sector appears inconsistent. Most of the local production is achieved thanks to large amounts of imported feedstuffs, and the Korean policy corresponds mainly to tariff escalation and income transfer rather than to FS concerns. The setting of self-sufficiency targets appears to be dominated by other strategies when pursuing FS.

Reliance on free trade with production targets is more rational and could provide the same level of protection to producers and reduce welfare cost to consumers. We found that the welfare gains to such a policy are considerable, even when maintaining present levels of production. Such a reorientation of policy instruments also would increase demand and hence exports from mercantilist trade partners who find current Korean policy of nearly prohibitive agricultural tariffs unpalatable.

To conclude, our policy recommendation is that members of the WTO who endorse FS should advocate deficiency payments for their agricultural production and open their borders. This strategy, which mirrors U.S. policy, would be much less antagonizing than strict self-sufficiency objectives for trade partners and more beneficial to consumers and small producers who are net buyers of food. Policy rents to farmers and landowners would be unaffected, which might help transition toward deficiency payments. Deficiency payments are a defendable second-best policy if the constraint is FS. If the stated objective of FS dissimulates other motives, such as transferring income from consumers to farmers and landowners, deficiency payments are less efficient than pure lump-sum transfers. Nevertheless these production subsidies constitute a major improvement compared to blunt instruments such as trade barriers.