An event-contingent method to track disfluency effects on the relationship and the self

Abstract

Background

Theoretically, reductions of self-esteem among people who stutter (PWS) are often explained by individual negative cognitions or emotions of the PWS or their conversation partners. We propose that the flow of a conversation can be seen as a representation of the relationship between speakers, and that by disrupting this flow, a stutter may directly threaten this relationship, and in turn affect self-esteem. Methodologically, we present a new, event-contingent, method that assesses fluctuations in self-esteem over time and thereby allows one to assess the predictive value of specific conversational experiences.

Aims

To have both a theoretical and a methodological contribution on conversational disfluency.

Methods & Procedures

Our focus is not on stable individual factors, but we expect that fluctuations within the flow of everyday conversations predict changes in self-esteem. We studied these fluctuations with an experience sampling method which prompted participants to answer a brief survey after each of 10 conversations in a 2-week period. Self-identified PWS (n = 58) and people who do not stutter (PWNS; n = 53) reported on their individual negative cognitions and emotions and experienced relational quality and state self-esteem in more than 1000 conversations. By assessing fluctuations in self-esteem over time, this method allows one to assess the predictive value of specific conversational experiences.

Outcomes & Results

Correlational evidence demonstrates that flow disruptions are associated with temporary reductions in self-esteem. This association is mediated by increased individual negative cognitions and emotions, as well as threatened social relationships. This appeared to be true for both PWS and PWNS, although PWS experienced on average less conversational flow and lower state self-esteem. On average, PWS did not experience lower relational quality than PWNS.

Conclusions & Implications

An event-contingent recording method is a useful way to assess momentary fluctuations in self-esteem. Findings are consistent with the notion that people monitor their relationship by attending to fluctuations in conversational flow; whereas a smooth conversational flow indicates a strong relationship, disruptions of flow (e.g., as caused by a stutter or other factors) signal a threat to the relationship.

What this paper adds

What is already known on the subject

- Even though adverse effects of stuttering on the experience of self-esteem have been reported, the evidence for this relation is equivocal. Because the evidence is mixed, it becomes interesting to examine the processes that provide insight in how stuttering may affect self-esteem. Theoretically, reductions of self-esteem among PWS are often explained by individual negative cognitions or emotions of the PWS or their conversation partners. Methodologically, studies examine this relation by single self-report measures, or by laboratory studies.

What this paper adds to existing knowledge

- Our theoretical model shows that the flow of a conversation can be seen as a representation of the relationship between speakers, and that by disrupting this flow, a stutter directly threatens this relationship, and in turn, affects self-esteem. Methodologically, we present a new, event-contingent, method that assesses fluctuations in self-esteem over time and thereby allows one to assess the predictive value of specific conversational experiences.

What are the potential or actual clinical implications of this work?

- Going beyond the study of stable individual cognitions and emotions of PWS and listeners, our findings show that a close examination of between-conversation fluctuations in flow can teach us about the day-to-day reality of people living with speech disorders, and the way they develop relationships and self-esteem.

INTRODUCTION

Even though adverse effects of stuttering on the experience of self-esteem have been reported (Bajina, 1995; Klompas & Ross, 2004), the evidence for this relation is equivocal. Several studies report lower self-esteem among people who stutter (PWS) (Blood et al., 2011; Corcoran & Stewart, 1998; Daniels et al., 2006; Klompas & Ross, 2004), while others report self-esteem levels of PWS to be within normal ranges (Blood & Blood, 2004; Blood et al., 2003; Boyle, 2013; Yovetich et al., 2000). Because the evidence is somewhat mixed, it becomes interesting to examine the processes that provide insight in when and how stuttering may affect self-esteem. Looking at when self-esteem is affected, it appears that relationships may play a role in buffering the effects of stuttering on self-esteem. For instance, Blood and Blood (2004) showed that adolescents who stuttered were at higher risk of being bullied than adolescents who do not stutter. Importantly, only those adolescents that were at risk of being bullied (that is, those experiencing negative relationship outcomes) experienced reduced self-esteem. Not only do negative relationship outcomes predict self-esteem reductions, positive relationship outcomes can also buffer self-esteem. Indeed, research showed that PWS who receive high social support are less likely to experience reductions in self-esteem (Craig et al., 2011). In other words: social relationships appear to moderate the effect of stuttering on self-esteem.

Considering the question why self-esteem is affected, explanations thus far have focused on the cognitive and emotional consequences of stuttering for the PWS and their interaction partners. On the cognitive side, PWS have been found to be susceptible to developing a self-stigma. This means that they come to view themselves in terms of the negative stereotype that exists about PWS, that is, that they are withdrawn, shy, and have low intelligence (Boyle et al., 2009). A self-stigma is especially likely to affect self-esteem when one tries to hide their stutter from their conversation partners (Corrigan et al., 2010). Moreover, PWS are likely to develop negative attitudes and anxiety towards communication, motivating them to prevent possible negative reactions by avoiding social interactions (Boey, 2008). This tendency to avoid social interaction may be augmented by a greater concern for failure that has been reported among PWS (Brocklehurst et al., 2015). On the emotional side, PWS are likely to experience anxiety, shame, and embarrassment in communication situations (Boyle et al., 2009; Ginsberg, 2000; Van Riper, 1982; Yaruss & Quesal, 2004). Thus, previous research has provided important insights on individual cognitions, emotional processes of PWS, and possible stereotypes held by the communication partners. Importantly, these studies approach stuttering as a problem of individuals, and view complications in social life as resulting from negative cognitions held by both the PWS and their conversation partners (Davis et al., 2002).

Taking a slightly different perspective, we propose that social relationships can also be directly affected by a stutter. Recent research in social psychology suggests that the social relationship between speakers may be directly threatened by disruptions of conversational flow. Conversational flow is defined as the extent to which a conversation is experienced as smooth, efficient, and mutually engaging (Koudenburg et al., 2014) Specifically, in this research it was shown that the flow of a conversation, in and of itself, is perceived as a signal about the quality of the relationship between speakers. In other words, people derive information about the quality of relationships through the subjective experience of a conversation as smoothly flowing (Koudenburg et al., 2011, 2013, 2017). The reasoning behind this is that most people are so well-versed at coordinating their speech in conversations, that any disruption of the normal flow of conversation (e.g., a brief silence) is interpreted as a signal for relationship problems. In research among PWNS, for instance, it was shown that introducing a 1 s delay on the line in computer-mediated communication was sufficient to raise questions about the relationship between speakers. Dyads whose interactions were disrupted by a 1 s delay felt that they were less on the same wavelength (i.e., aligned with each other), and experienced lower relationship quality than those who had interacted without a delay (Koudenburg et al., 2013). Importantly, these effects occurred even when participants were made aware of the source of the disruption. In two studies, an experimenter either told participants that there might be connection problems, or participants received a computer warning that the connection was bad at the moment the delay was introduced. Despite these warnings, dyads still experienced lower relationship quality when conversational flow was disrupted. Extrapolating this to conversations of PWS, this suggests that a stutter could directly affect processes at the relational level: By disrupting conversational flow, stuttering should decrease experienced relationship quality, and in turn, reduce self-esteem. This could happen despite interaction partners being aware of the source of the disfluency.

The present research

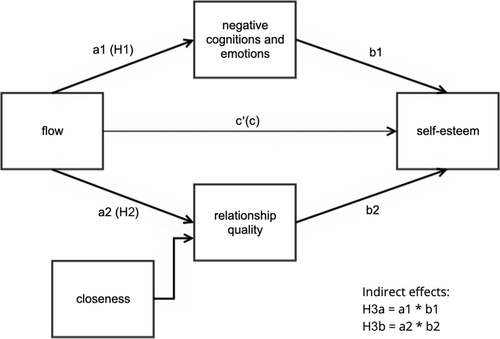

So far, scholars have outlined the cognitions and emotions that PWS may develop with regard to social interactions, and, as a consequence of this, difficulties they may experience in forming and maintaining social relationships (Adriaensens et al., 2015). We propose a new theoretical model (Figure 1) that suggests that social relationships can also be directly affected by disruptions of conversational flow that are caused by a stutter. And, because research in psychology demonstrates that meaningful relationships are key to the development of self-esteem (Leary & Baumeister, 2000; Yeung & Martin, 2003), these flow disruptions are subsequently expected to explain fluctuations in state self-esteem.

Specifically, we suggest that disruptions of conversational flow may prompt people to raise questions about the social relationships among speakers. We build on recent research showing that people perceive the flow of a conversation to contain important information about the relationship between speakers (Koudenburg, Postmes, & Gordijn, 2011, 2013, 2017). Extending this argument, we suggest that by disrupting conversational flow, a stutter may directly threaten the relationship between speakers, and in extension, affect self-esteem. This process should be the same for PWS and people who do not stutter (PWNS) alike, but the frequency and severity of flow disruptions is likely to be higher among PWS.

This new theorizing has important consequences for the way we measure the effects of stuttering on self-esteem. Indeed, when testing whether stuttering affects self-esteem through cognitions and emotions that lead PWS to avoid social contact, these processes can be argued to be quite stable, and general trait measures of self-esteem may be suitable. In line with this, most previous studies comparing PWS and PWNS have used trait measures of self-esteem (e.g., Blood & Blood, 2004; Boyle, 2013). However, if, as we suggest, self-esteem can also be affected by momentary fluctuations in the flow of a conversation that signal that relationships may be threatened, a more event-contingent measure of state self-esteem is needed (e.g., Gergen, 1971; Leary & Baumeister, 2000). By using an experience sampling method, the present study is sensitive to tracking the predictive value of specific conversational experiences on individual negative cognitions and emotions, as well as on social relationships, to test their unique value in predicting self-esteem.

The present research used an experience sampling method to examine processes at both the individual and relational level in explaining the relationship between flow disruptions and self-esteem. Previous researchers have studied stuttering in laboratory settings or through self-report, but not in daily life. Experience sampling aims to systematically obtain self-report data on participants’ experiences at multiple time points in their everyday lives (Larson & Csikszentmihalyi, 2014). It allows for collecting multiple repeated measurements within individuals, and is therefore very suitable for detecting momentary fluctuations in psychological variables. We used experience sampling because our focus is not on stable individual factors, but we expect that fluctuations within the flow of everyday conversations predict changes in self-esteem. We hypothesize these processes to be similar for both PWS and PWNS. Therefore, we collected conversational data from a PWS sample and a PWNS sample and test the model in both samples. We hypothesized that, for both samples, a reduced experience of conversational flow predicts increases in the experience of failure and shame (individual cognitions and emotions path; H1), a decreased experience of relationship quality (relationship path, H2). Finally, both paths should explain reductions in self-esteem (H3). We also explore between-sample differences in the experience of self-esteem and conversational flow. However, because of slight differences in sampling strategy, and demographics between samples, we will not draw any firm conclusions based on such differences.

METHODS

Participants

The sample characteristics divided for the PWS and the PWNS are described in Table 1. Anyone older than 16 could participate; participants were divided into the PWS or PWNS group based upon self-identification. The total sample consisted of 111 participants who reported on a total of 1008 conversations (mean = 9.08, SD = 3.11), with an average duration of 20.63 min (SD = 32.00 min), and with a diversity of conversation partners (179 family members, 263 friends, 134 acquaintances, 214 colleagues and 218 strangers). A number of gifts were raffled among all participants to thank them for participating. All anonymized data are available at DataverseNL (https://doi.org/10.34894/FYRGDY).

| PWNS | PWS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | (SD) | Count | Mean | (SD) | Count | ||

| Age | 22.64 | (4.00) | 30.47 | (11.69) | |||

| Gender | Female | 29 | 19 | ||||

| Male | 24 | 39 | |||||

| # of conversations reported | 9.17 | (3.02) | 9.00 | (3.23) | |||

| Duration of conversation (min) | 23.17 | (38.53) | 18.26 | (24.20) | |||

| Closeness of conversation partner | 3.34 | (1.43) | 3.22 | (1.52) | |||

| Relationship to conversation partner | Family | 75 | 104 | ||||

| Friend | 158 | 105 | |||||

| Colleague | 106 | 108 | |||||

| Acquaintance | 54 | 80 | |||||

| Stranger | 93 | 125 | |||||

- Note: PWS, people who stutter; PWNS, people who do not stutter.

PWS sample

Participants (n = 58, Mage = 30.47, SDage = 11.69) were recruited from a network of a speech therapist and via social media pages. A total of 19 females and 39 males participated. Most PWS were attracted through pages related to stuttering, for instance, the YouTube channel Broca Brothers (1720 subscribers). The majority of the sample was European (59%, of whom 29% Dutch), others were Asian (12%), Northern American (7%), Australian (5%), African (5%), or Latin-American (3%).

PWNS sample

Most PWNS (n = 53, Mage = 22.64, SDage = 4.00) were recruited via personal networking sites, for instance, Facebook pages. A total of 29 females and 24 males participated. A large majority of the sample was European (94%, of which 79% Dutch), the remaining participants were Asian (2%) or Northern American (4%).

The PWS sample was significantly older than the PWNS sample (t(109) = –4.63, p < 0.001) and the PWS sample had proportionally more men than the PWNS sample (χ2(1, N = 111) = 5.44, p = 0.020). The number of conversations per type of relationship also differed for PWS and PWNS (χ2(4, N = 1008) = 13.88, p < 0.001) (Table 1). No other between-sample differences emerged for the characteristics of the participants, such as conversation duration (b = –5.61, SE = 3.15, t(109) = –1.78, p = 0.078, 95% CI [–11.85, 0.63], Cohen's d = –1.03), number of conversations (t(109) = 0.29, p = 0.776), or closeness to the conversation partner (b = –0.08, SE = 0.09, t(109) = –0.91, p = 0.364, 95% CI [–0.89, 0.98], Cohen's d = –0.09).

Procedure

We used an experience-sampling method to assess the effects of conversational flow on participant self-esteem. Participants completed an initial questionnaire asking for their informed consent and demographics, including a question assessing whether they stuttered (yes/no). Afterwards, they were invited to download the app ‘Track your Conversations’. This simple app was specifically designed for this study and consisted of a brief questionnaire, which participants were instructed to complete as soon as possible after a conversation. They were asked to report on at least 10 conversations in the 2 weeks after downloading the app.1 We pointed out that they could report any conversation, with any conversation partner.

Questionnaire

First, participants estimated the duration of the conversation. To assess the variables of interest, participants were then given a list of eleven statements to which they could indicate their agreement on a scale from 1 = disagree, to 5 = agree. To assess flow, participants indicated their agreement with the statement ‘the conversation was flowing smoothly’. When participants reported low levels of flow (a score of 1 or 2), an extra question appeared asking participants to indicate why this was the case: ‘Because of: me/the other person/both of us/something in the environment’.

We assessed relationship quality by averaging the scores across four items: ‘I had the feeling that the other person(s) and I were on the same wavelength’, ‘during the conversation, I identified with the other person(s)’, ‘During the conversation, I felt a sense of belonging with the other person(s)’, ‘During the conversation, I experienced a sense of unity with the other person(s)’ (Cronbach's α = 0.91; Koudenburg, et al., 2013; Postmes et al., 2013). Two items measured individual negative cognitions and emotions ‘I experienced a sense of failure during the conversation’, ‘I felt ashamed of myself during the conversation.’ (Pearson's r = 0.75, scores were averaged across the two items). Two items assessed self-esteem, ‘Right now, I have high self-esteem’ (Robins et al., 2001) and ‘Right now, I feel good about myself’ (Pearson's r = 0.84, scores were averaged across the two items). For exploratory purposes we also measured whether participants felt they could express themselves freely in the conversation and felt the other person valued their input in the conversation. Because these items were not of central interest, we did not include them in the analysis. Finally, as a control variable, we assessed prior closeness with the conversation partner by asking participants how well they knew the person(s) they had talked to (1 = not at all, 5 = very well). Participants also indicated the nature of the relationship with their conversation partners (family/friend/acquaintance/colleague/stranger). After filling out the questionnaire, participants were given the opportunity to leave remarks about the conversation.

Participants who reported that they stuttered answered one additional question assessing whether they experienced that they were speaking fluently during each conversation on a scale from 1 = not fluent at all, to 5 = very fluent. Lack of fluency in speech is a common experience among PWS. In this research we focus on conversational flow more generally, because this should affect both PWS and PWNS in similar ways. For PWS, we expected that the experienced lack of flow would result from the lack of fluency in their own speech. Supporting this assumption, we found a correlation of r = 0.70, p < 0.001 between flow and fluency and we found that a large majority of the PWS (74.32%) ascribed the lack of flow as caused by themselves.

Data analysis plan

Power analysis

For a multilevel structure in which conversations are nested within participants, power is not only determined by effect size, but also by interclass correlations (i.e., variance explained within and between participants). Because we had no prior data with a similar multilevel structure and similar measurements, we were unable to calculate sample size a priori. To get an impression of the robustness of the current data, we iteratively fit the multilevel model to subsets of our data. We explored the robustness of three important relations in our multilevel model. The sensitivity explorations suggest that significant effects of flow on self-esteem and on relationship quality (while controlling for closeness) are found reliably (i.e., in > 99.7% of the iterations) in random permutations of our data that include as few as 20 participants. A significant effect of relationship quality on self-esteem (controlling for flow and individual negative cognitions and emotions) is found reliably (i.e., in > 90% of the iterations) in random permutations of our data that include 50 participants.

Exploring differences between the PWS and PWNS sample

We explored differences between the PWS with PWNS samples, with Multilevel Modelling with the standardized measures per conversation (level 1) nested within participants (level 2), to correct for interdependence of the measurements. We compared models with and without random slopes and tested their model fit. We used the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) values to determine model fit and found that in all cases adding random slopes did not improve the model fit, that is, for flow, individual negative cognitions and emotions, self–esteem, and relationship quality BICfixed slopes – BICrandom slopes produced negative values between –12 and –3, showing positive to very strong indications that the models with fixed slopes fit the data better. Moreover, conclusions did not differ between models with random and fixed slopes, suggesting that the effects of the predictor variable do not vary substantially between individual participants. We therefore report the models with fixed slopes only. We calculated the effect size Cohen's d (0.2 is considered a small effect, 0.5 = a medium effect and 0.8 a large effect; Cohen, 1992) by dividing the regression coefficient by the square root of the within group residual variance (Tymms, 2004).

Testing the model (H1–H3)

To test whether relationship quality and individual negative cognitions and emotions mediated the relationship between flow and self-esteem, we performed a multilevel mediation (1-1-1 model; Preacher et al., 2010). Prior closeness with the conversation partner was included as a covariate for relationship quality in the model. Because we found no evidence for a prior closeness by flow interaction on relationship quality (b = 0.10, n.s., Cohen's d = 0.12), the interaction term was not included in the final model. Again, we ran the model with and without random slopes and looked at the BIC value to determine best model fit. For all models the simplest model, with the fixed slopes, had the best fit, BICfixed slopes – BICrandom slopes = –23.14, suggesting that modelling individual variation in the effects did not improve our model. Because the measures in the model are on conversational level, and not participant level, and we are interested in the conversational effects, we report the within-level effects.

RESULTS

Attributions of flow disruptions

For conversations with low flow (score 1 or 2 out of 5) PWS indicated in 74.32% of the conversations that this was because of themselves (against 2.7% attributed to the other person and 12.16% to both speakers). For PWNS, only 9.09% indicated that this was because of themselves. They were more likely to attribute the lack of flow to both speakers (43.18%) or to the other person (31.82%). The environment was held responsible in only 15.91% of the cases among PWNS, and 10.81% among PWS.

Comparing the PWS and PWNS samples

Means are summarized in Table 2. All variables are standardized before analyses, all b-coefficients are estimated at Level 2 (the individual level), and thus reflect standardized differences between individuals as predicted by their group membership (PWS versus PWNS). As hypothesized, compared with our PWNS sample, the PWS sample reported significantly lower state self-esteem (H1), b = –0.28, SE = 0.13, t(109) = –2.05, p = 0.043, 95% CI [–0.54, –0.01], Cohen's d = –0.32 and less conversational flow (H2), b = –0.30, SE = 0.10, t(109) = –3.11, p = 0.002, 95% CI [–0.48, –0.11], Cohen's d = –0.31. PWS also experienced more negative cognitions and emotions, b = 0.58, SE = 0.11, t(109) = 5.23, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.36, 0.80], Cohen's d = 0.64. We found no significant differences on the experienced relationship quality with their conversation partner, b = –0.07, n.s., Cohen's d = –0.08. Effects on self-esteem and conversational flow fell into the range of small to medium effects, whereas the effect on negative cognitions and emotions represented a medium to large effect size.

| Sample | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PWNS | PWS | |||||

| Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | d | ICC | |

| Flow | 3.99 | (1.05) | 3.67 | (1.02) | –0.31** | 0.18 |

| Negative cognitions/emotions | 1.58 | (0.80) | 2.20 | (1.24) | 0.64*** | 0.33 |

| Relationship quality | 3.68 | (1.06) | 3.61 | (1.08) | –0.08 | 0.12 |

| Self-esteem | 4.03 | (0.82) | 3.79 | (1.00) | –0.32* | 0.43 |

- Note: PWS, people who stutter; PWNS, people who do not stutter.

- ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Testing the model

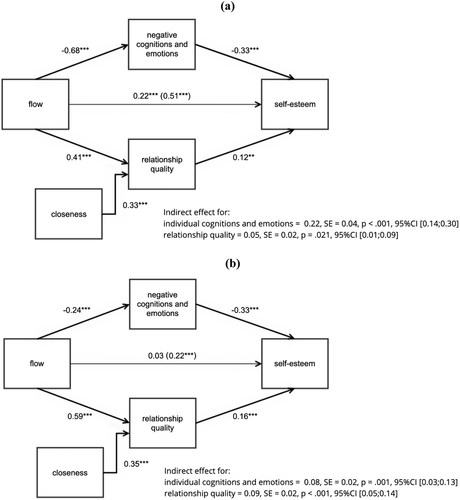

Figure 2 displays the mediation models for the PWS sample (a) and the PWNS sample (b).2 Here, b-coefficients indicate the change at Level 1, the level of the conversation (e.g., it reflects the increase in self-esteem with 1 SD increase in flow), while taking into account random intercepts (i.e., individual differences in the DV that are stable across the measurements).

Mediation model for the PWS sample (a) and the PWNS sample (b). Standardized multilevel regression coefficients are shown. The total effect of flow on self-esteem is shown in the parentheses

Note: **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

PWS sample

First, in the PWS sample, flow was negatively associated with individual negative cognitions and emotions (H1), b = –0.68, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001, 95% CI [–0.78, –0.59], which was in turn negatively associated with self-esteem b = –0.33, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001, 95% CI [–0.43, –0.22]. The indirect association between flow and self-esteem via individual negative cognitions and emotions was significant, and estimated at 0.22, SE = 0.04, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.14, 0.30]. (H3a) Flow was positively associated with relationship quality (controlling for prior closeness, H2), b = 0.41, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.32, 0.50], which was in turn positively associated with self-esteem b = 0.12, SE = 0.05, p = 0.008, 95% CI [0.03, 0.22]. The indirect association between flow and self-esteem via relationship quality was also significant, and estimated at 0.05, SE = 0.02, p = 0.021, 95% CI [0.01, 0.09].

PWNS sample

The model was replicated in the PWNS sample. Flow was negatively associated with individual negative cognitions and emotions (H1), b = –0.24, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001, 95% CI [–0.34, –0.15], which was in turn negatively associated with self-esteem, b = –0.33, SE = 0.06, p < 0.001, 95% CI [–0.44, –0.22]. The indirect association between flow and self-esteem via individual negative cognitions and emotions was significant, and estimated at (0.08, SE = 0.02, p = 0.001, 95% CI [0.03, 0.13], (H3a). Flow was positively associated with relationship quality (controlling for prior closeness, H2), b = 0.59, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.49, 0.68], which was in turn positively associated with self-esteem, b = 0.16, SE = 0.04, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.08, 0.23]. The indirect association between flow and self-esteem via relationship quality was also significant, and estimated at 0.09, SE = 0.02, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.05, 0.14].

In other words, among both PWS and PWNS, reduced flow is associated with increased individual negative cognitions and emotions, reduced relationship quality, and reduced self-esteem. However, our PWS sample experienced on average lower levels of flow in their conversations, which could explain their reductions in self-esteem compared with our PWNS sample.

DISCUSSION

Previous research has examined stuttering in laboratory settings or through one-time self-report assessments, but not in daily life. We employed a novel event-contingent recording method for assessing the predictive value of flow disruptions during everyday social encounters for explaining fluctuations in self-esteem among both PWS and PWNS. Findings are consistent with the notion that people monitor their relationship by attending to fluctuations in conversational flow: whereas a smooth conversational flow indicates a strong relationship, disruptions of flow (e.g., as caused by a stutter or other factors) signal a threat to the relationship.

Importantly, the present study is the first to show that through its negative impact on relationship quality, disruptions of flow also predict reductions in speakers’ self-esteem. Although flow disruptions occur in many conversations and can be caused by a variety of factors, they were more commonly reported in our PWS sample, and PWS were also more likely to attributed flow disruptions to themselves, rather than their interaction partner or the situation. Our PWS sample also experienced reduced self-esteem compared with our PWNS sample. It is important to note that differences in demographical characteristics and recruitment strategies between the samples limit the generalizability of our findings to the population of PWS and PWNS. However, we can use our model (which applies to both samples, as well as the combined sample) to explain differences between these specific samples. Indeed, our PWS sample scored lower on both conversational flow and self-esteem. The model suggests that the lesser experienced flow in conversation in our PWS sample can explain reductions in self-esteem through two processes: an increase in negative cognitions and emotions, and an increased difficulty to maintain social relationships through conversation. Although conversation partners are likely aware of the cause of flow disruptions (i.e., the stutter), they seem unable to correct for the impact of these disruptions on their relationship experiences and their self-esteem (see also Koudenburg et al, 2013).

The main aim of this research was to explain temporary fluctuations in self-esteem, in both PWS and PWNS, through a model that includes both individual and relational consequences of flow disruptions. Importantly, we did not expect, nor find, that the quality of relationships was lower among PWS than among PWNS. This is in line with previous research showing that the majority of adolescents who stutter feel that their stuttering did not have an impact on whether people liked them, wanted to be friends with them, or would invite them to a party or date (Blood et al., 2003). Possibly, PWS develop strategies to deal with a lack of communicative competence that enable them to engage in positive relationships (Blood & Blood, 2004). In the present study, we found a small to medium-sized effect suggesting a decreased self-esteem among PWS (compared with PWNS). Because previous research obtained mixed evidence for this relation (Blood et al., 2011; Klompas & Ross, 2004; Yovetich et al., 2000), and because our samples were not matched on important characteristics (for instance, our PWS sample was older than the PWNS sample), caution should be taken in interpreting such comparisons between groups. We therefore believe that the main contribution of this research lies in explaining when reductions in self-esteem may occur. That is, rather than comparing between individuals, we examine the influence of fluctuations in conversational flow within the same individuals. The present study shows that, for PWS and PWNS alike, reduced conversational flow is related to more negative individual cognitions and emotions, and to more negative inferences about the relationship which both explain reductions in self-esteem. The only difference is that, compared with PWNS, PWS are more likely to experience reduced conversational flow, and therefore, are more likely to experience these adversary consequences to their self-esteem after a conversation.

Limitations and future directions

Because our data are correlational, we cannot make strong claims about the causality of the examined relationships. Indeed, previous research has demonstrated a vicious cycle of low self-esteem and compromised social relationships (Harris & Orth, 2019), suggesting that the reverse causal path, in which self-esteem predicts how social relationships are experienced may in part account for our findings. Moreover, fluctuations in self-esteem may predict when people stutter, leading to lower experiences of conversational flow. Although we cannot exclude these possibilities, and it is likely that both causal pathways co-occur, we have reason to believe that the pathway we theorized, where flow disruptions predict relationships and self-esteem, is at least part of the explanation of the correlation. This reason is grounded in theorizing from which we draw our hypotheses (Koudenburg et al., 2011, 2013, 2017). This theorizing was based on seven empirical studies in which flow was manipulated among PWNS, and in which a causal effect of flow disruptions on the experience of social relationships was established.

The study examined the associations between reductions in flow and self-esteem in a 2-week time period, with an average of nine reported conversations per participant. While this is a common time frame for experience sampling on, for instance, self-esteem (e.g., Thewissen et al., 2008) one might expect to register larger fluctuations in self-esteem when monitoring for a longer period of time. In addition to the limited period of sampling, we limited the number of items in each questionnaire, assessing most constructs with short two-item measures. While this is common practice in research involving multiple repeated measures (Robins, et al., 2001), on may be concerned about the validity and reliability of these measures. However, research suggests that short scales can be just as reliable and valid as long instruments (Burisch, 1984, 1997) depending on the nature of the construct operationalized. For self-esteem, relationship quality and conversational flow, we therefore used previously validated measures (Koudenburg et al., 2013; Postmes et al., 2013; Robins et al., 2001). We did not have such a measure available for negative emotions and cognitions, and therefore we developed two items that, after careful consideration of the literature on stuttering, we considered most central in a conversational context (Boyle et al., 2009; Brocklehurst, 2015; Ginsberg, 2000; Van Riper, 1982; Yaruss & Quesal, 2004). Future research could focus on further testing the relations in our model on more specific negative emotions and cognitions.

Because of the importance of the smooth flow of conversations, people may be very motivated to retain conversational flow. For PWS, this may mean that one may rather avoid speaking (or at least avoid certain words or sounds), rather than disrupting the flow of a conversation. While such behaviours may serve conversational flow, it is possible that they may also have negative emotional or cognitive consequences. The consequences of efforts to maintain conversational flow could be an avenue for future research.

CONCLUSIONS

Previous research revealed that stuttering provides discomfort for both PWS and listener (Plexico et al., 2009), but consequences at the relationship level were largely ignored. Going beyond the study of stable individual cognitions and emotions, our findings show that a close examination of between-conversation fluctuations in flow can teach us about the day-to-day reality of people living with speech disorders, and the way they develop relationships and self-esteem.