Interleukin IL-1B gene polymorphism in Tunisian patients with chronic hepatitis B infection: Association with replication levels

Abstract

Approaches based on association studies have proven useful in identifying genetic predictors for many diseases, including susceptibility to chronic hepatitis B. In this study we were interested by the IL-1B genetic variants that have been involved in the immune response and we analyzed their role in the susceptibility to develop chronic hepatitis B in the Tunisian population. IL-1B is a potent proinflammatory cytokine that plays an important role in inflammation of the liver. Polymorphic gene IL-1 (−511, +3954) was analyzed in a total of 476 individuals: 236 patients with chronic hepatitis B from different cities of Tunisia recruited in Pasteur Institute between January 2017 and December 2018 and 240 controls. Genomic DNA was obtained using the standard salting-out method and genotyping was performed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-restriction fragment length polymorphism. For −511C>T polymorphism a significant association was found between patients and controls when comparing the genotypic (P = 0.007; χ2 = 9.74 and odds ratio [OR] = 0.60; confidence interval [CI] = 0.41–0.89) and allelic (P = 0.001; χ2 = 10.60) frequencies. When the viral load was taken into account a highly significant difference was found (P = 9 × 10−4; χ2 = 10.89). For +3954C>T polymorphism a significant association was found between patients and controls when comparing genotypic (P = 0.0058; χ2 = 7.60 and OR = 1.67; CI = 1.14–2.46) and allelic (P = 0.0029; χ2 = 8.81) frequencies. T allele can be used as a strong marker for hepatitis B virus disease for both polymorphisms.

1 INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a serious public health problem worldwide and a major cause of chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. It is estimated that over 2 billion people have been exposed to the virus among which around 350 million are chronically infected and around 780,000 die every year.1 The variations in the clinical outcome of HBV infection is multifactorial; it is determined by virological, immunological, and host genetic factors.2, 3 HBV clearance also depends on an effective host immune response4 and, thus, ineffective host immunity leads to chronic infection and may create a hepatic microenvironment favoring the development of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma.5, 6

Several reports have raised questions about the role of the host-related genetic background in host–pathogen interactions and in the pathogenesis of hepatitis B.7-11 Efforts are yet to be made to find powerful genetic susceptibility biomarkers.12 The inflammatory reaction in infectious and autoimmune diseases is regulated by a delicate balance between the proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines.13-15 While several immune mediators influence the development of tissue inflammatory responses, IL-1B is likely to be a major cytokine involved in most inflammatory responses. It is the most potent proinflammatory cytokine and an important mediator of the inflammatory response that exerts pleiotropic effects on a variety of cells and plays key roles in acute and chronic inflammatory and autoimmune disorders; it is involved in a variety of cellular activities, including cell proliferation, immunoglobulin synthesis, and T-cell activation,16 that modulate the outcome of HBV infection. Recent findings implicate IL-1B in painful and inflammatory processes at multiple levels, both peripherally and centrally.17 IL-1B inhibition could represent a broad-acting and efficacious method for managing pain and inflammation across a wide variety of conditions. IL-1B plays an important role in inflammation of the liver18 and is produced mainly by stimulated monocytes, macrophages, keratinocytes, smooth muscle, and endothelial cells.19

The gene coding for IL-1B (IL-1B) has two base-exchange polymorphisms, at position −511 in the promoter region (rs16944) and at position +3954 in exon 5 (rs1143634).20 These two polymorphisms have potential functional significance in modulating IL-1 protein production and were associated with the development of some diseases such as nonsmall cell lung cancer,21 cervical cancer,22 Alzheimer's disease,23 and acute graft-versus-host disease.24 Previous reports have suggested the role of IL-1B polymorphisms in the development of chronic hepatitis B.25, 26 IL-1B polymorphisms were also associated with hepatocyte damage that may finally lead to the development of hepatocellular carcinoma.25, 26 It was suggested that high production of IL-1B may help increase the production of other cytokines such as IL-2, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α and trigger the complex immunological process to eliminate HBV.27 To date, only few studies have been conducted to investigate the role of IL-1B polymorphisms in patients with chronic hepatitis B.

According to serological studies conducted until the early 1990s, Tunisia was classified among countries with intermediate endemicity for HBV; the published rates of HBV surface antigen (HBsAg) positives in blood donors and the general population ranged from 4% to 7%. The overall prevalence rates of antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc), HBsAg, and chronic carriage were 28.5%, 5.3%, and 2.9%, respectively.28 Systematic vaccination of newborns was introduced in 1995 and, recently, a nationwide serosurvey29 showed a significant decrease in HBsAg seroprevalence as a consequence of these vaccinations strategies. However, hepatitis B still represents a serious public health problem due to the already constituted high number of chronic carriers, especially among people born before 1995. Because no previous study has been conducted in North African population and especially in Tunisia, the present work assessed polymorphisms of the IL-1B gene in patients with chronic hepatitis B and their association with virological and host factors, as compared with HBsAg-negative controls.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Patients, controls, and sampling

The patient group included 236 chronic HBV carriers (HBsAg and anti-HBc positives two times at least 6 months apart) and referred to the Laboratory of Virology in Pasteur Institute (Tunisia) between January 2017 and December 2018 for HBV viral load, as part of a pretherapeutic investigation. The patient group originated from different cities of Tunisia and included 117 males aged between 18 and 110 years (mean = 48.61 years) and 119 females aged between 26 and 86 years (mean = 43.17 years). HBV DNA levels were measured using the High-Pure COBAS TaqMan commercial Kit from Roche Molecular Systems (USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Results were recorded in international units per milliliter (IU/ml); 1 IU corresponds to 5.6 viral copies. Patients were divided into two groups according to their viral load with an arbitrary threshold value of 2000 IU/ml. Group 1 included patients with a viral load below 2000 IU/ml (N = 182) and Group #2 included patients with a viral load over 2000 IU/ml (N = 54). The threshold 2000 IU/ml was proposed by the Tunisian Society of Gastroenterology and the National Institutes of Health Conference to classify patients as inactive HBV carriers or active replicating carriers.30

The control group was composed of 240 age-related and sex-matched healthy individuals who came to the institute for routine laboratory investigations. The control group was composed of 96 males aged between 27 and 80 years (mean = 51.24 years) and 144 females aged between 18 and 80 years (mean = 45.88 years).

A questionnaire was used to exclude patients with known hepatitis history or with symptoms of possible ongoing infection. All individuals from the control group were then screened for serum HBsAg using a commercial ELISA test kit (Monolisa HBs Ag ULTRA, BIORAD, France) and only negatives were retained in the control group. Demographic data and viral load values are presented in Table 1.

| HBV patients (%) | Controls (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| N = 236 | N = 240 | |

| Mean age (year) | 45.7 | 46.6 |

| Gender | ||

| Females | 119 (50.4) | 144 (60) |

| Males | 117 (49.6) | 96 (40) |

| Viral load | ||

| >2000 IU/ml (Group 1) | 54 (22.8) | – |

| <2000 IU/ml (Group 2) | 182 (77.1) | – |

- Abbreviation: HBV, hepatitis B virus.

Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants prior to their enrolment in the study. The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Pasteur Institute of Tunis.

From each patient and control 5 ml of venous blood with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, as anticoagulant, were collected. Plasma samples were split into two aliquots for molecular analyses and stored at −20°C until use.

2.2 Genotyping for single-nucleotide polymorphism of IL-1B

Molecular genetic analyses were performed on the genomic DNA obtained from the patient's peripheral blood leukocytes using the standard salting-out method as previously described.31

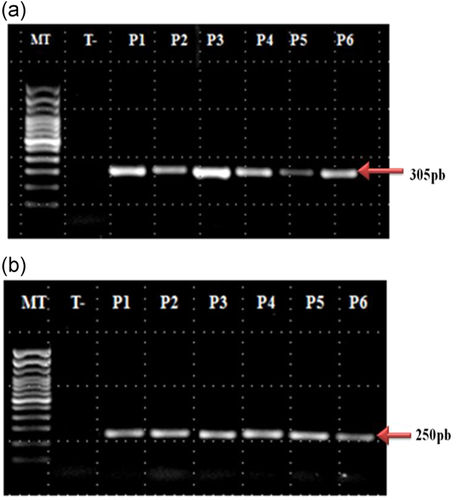

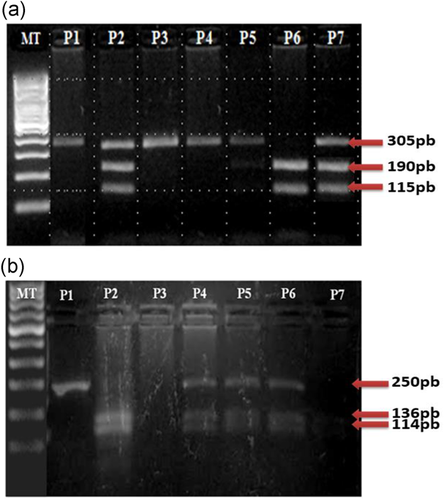

IL-1B -511: A fragment containing the AvaI polymorphic site at position −511 of the IL-1B gene was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with a sequence-specific primer (Table 2).32 The PCR cycling conditions were as follows: an initial denaturation step at 94°C for 2 min followed by 35 cycles at 94°C for 20 s, 59°C for 50 s, 72°C for 20 s, and a final extension at 72°C for 7 min. PCR amplicons were then restricted by the restriction enzyme AvaI (CarthaGenomics, Tunis). Digestion fragments were separated by electrophoresis on 3% agarose with ethidium bromide staining using appropriate commercially available size markers for comparison. Each allele was identified according to its size (Table 2). Genotypes were designated as follows: C/C, two bands of 92 and 63 bp; C/T, three bands of 155, 92, and 63 bp; and T/T, a single band of 155 bp.

| Gene | Polymorphisms | Primers | Restriction enzymes | Length of the restriction fragments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-1B | −511 | Forward: | AvaI | −511 (allele C): 92 bp + 63 bp |

| F-5′-TCATCTGGCATTGATCTGG-3′ | ||||

| Reverse: | −511 (allele T): 155 bp | |||

| R-5′-GGTGCTGTTCTCTGCCTCGA-3′ | ||||

| +3954 | Forward: | TaqI | +3954 (allele C): 114 bp + 136 bp | |

| F-5′-GTTGTCATCAGACTTTGACC-3′ | ||||

| Reverse: | +3954 (allele T): 250 bp | |||

| R-5′-TTCAGTTCATATGGACCAGA-3′ |

- Abbreviation: RFLP, restriction fragment length polymorphism.

IL-1B +3954: A fragment containing the TaqI polymorphic site at position +3954 of the IL-1B gene was amplified by PCR with a sequence-specific primer (Table 2).33, 34 The PCR conditions were as follows: an initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 58°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s, and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. PCR amplicons were then restricted by the restriction enzyme TaqI (CarthaGenomics, Tunis). Digestion fragments were separated by electrophoresis on 5% agarose with ethidium bromide staining using appropriate commercially available size markers for comparison. Each allele was identified according to its size (Table 2). Genotypes were designated as follows: C/C, two bands of 114 and 136 bp; C/T, three bands of 250, 114, and 136 bp; and T/T, a single band of 250 bp.

2.3 Statistical analysis

Differences in alleles and genotypes frequencies between patients and controls were compared using the standard chi-squared test (EPISTAT statistical package). When the expected cell number was less than 5, Fisher's exact test was used. Probability values of .05 or less were regarded as statistically significant. The strength of a gene association was assessed by the odds ratio (OR). The OR and the 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated whenever applicable.

3 RESULTS

All patients and controls were genotyped for IL-1B at positions −511 and +3954 (Figures 1 and 2). The Hardy–Weinberg principle was in equilibrium state for both groups (patients and controls) and for the two single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNPs) of IL-1B. The distributions of genotype and allele frequencies are presented in Table 3.

| Genotype frequency (%) | χ2 | Allelic frequency (%) | χ2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP | C/C | C/T | T/T | (P) | C | T | (P) |

| −511C>T | |||||||

| Patients with HBV (N = 236) | 76 (32.2) | 107 (45.3) | 53 (22.6) | 9.74 | 259 (54.8) | 213 (45.2) | 10.60 |

| Controls (N = 240) | 106 (44.3) | 101 (42) | 33 (13.7) | (0.007) | 313 (65.3) | 167 (34.7) | (0.001) |

| +3954C>T | |||||||

| Patients with HBV (N = 236) | 28 (11.9) | 94 (39.8) | 114 (48.3) | 7.60 | 150 (31.8) | 322 (68.2) | 8.81 |

| Controls (N = 240) | 43 (17.9) | 111 (46.3) | 86 (35.8) | (0.0058) | 197 (41.1) | 283 (58.9) | (0.0029) |

- Note: The bold values indicate that there is a statistically significant difference between frequencies.

- Abbreviations: HBV, hepatitis B virus; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

For the −511C>T polymorphism, when comparing genotypes frequencies between HBV patients and controls, a significant association was found (P = 0.007; χ2 = 9.74 and OR = 0.60; CI = 0.41–0.89); these values were obtained when the C/C genotype was compared with the C/T+T/T genotypes. The C/T genotype was the most frequently observed with a frequency of 45.3% in patients as compared with the C/C and T/T genotypes. In the control group, the most frequently observed was the C/C genotype (44.3%) as compared with the C/T and T/T genotypes. The C/C genotype was common in the control group as compared with the patient group, 44.3% and 32.2%, respectively. This difference was highly significant using the chi-squared test for comparing the allelic frequencies between patients and controls (P = 0.001; χ2 = 10.60).

Considering the +3954C>T polymorphism, genotype T/T was the most frequently observed in patients with a frequency of 48.3% and a significant association was found when the patient group was compared with the control group (P = 0.0058; χ2 = 7.60 and OR = 1.67; CI = 1.14–2.46). When considering the allelic frequencies, the T allele was most common in patients than in controls (68.2% vs. 58.9%, respectively) and a highly significant difference was found using the chi-squared test (P = 0.0029; χ2 = 8.81) when comparing both groups.

When patients were stratified according to age and sex, no significant association was found. By contrast, for the −511 C>T polymorphism when patients were stratified based on their viral load, a highly significant difference was found (P = 9 × 10−4; χ2 = 10.89) for genotypic frequency. Significant association was found when comparing allelic frequencies between both groups (P = 0.01; χ2 = 5.9; Table 4). The T allele was most common in patients with a viral load greater than 2000 IU/ml, with a value of 55.5%, as compared to patients with a viral load below 2000 IU/ml (42.3%). Considering the +3954C>T polymorphism, no significant association was found when patients were stratified based on their viral load (Table 4).

| Genotype frequency (%) | χ2 | Allelic frequency (%) | χ2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP | C/C | C/T | T/T | (P) | C | T | (P) |

| −511C>T U/ml | |||||||

| Group 1 <2000 (n = 182) | 65 (35.7) | 80 (44) | 37 (20.3) | 10.89 | 210 (57.7) | 154 (42.3) | 5.9 |

| Group 2 >2000 (n = 54) | 17 (31.5) | 14 (25.9) | 23 (42.6) | 0.0009 | 48 (44.45) | 60 (55.5) | 0.01 |

| +3954C>T U/ml | |||||||

| Group 1 <2000 (n = 182) | 85 (46.7) | 78 (42.9) | 19 (10.4) | 2.52 | 248 (68.1) | 116 (31.9) | 1.01 |

| Group 2 >2000 (n = 54) | 24 (44.4) | 20 (37.1) | 10 (18.5) | 0.11 | 68 (62.9) | 40 (37.1) | 0.31 |

- Note: The bold values indicate that there is a statistically significant difference between frequencies.

- Abbreviation: SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

4 DISCUSSION

With the growing number of studies on viral infectious diseases, the importance of host genetic polymorphisms has become pertinent. To the best of our knowledge, only 13 studies25-27, 32-41 conducted in six countries (China, Japan, Thailand, Iran, Turkey, and India) reported the role of IL-1B polymorphism in HBV chronic infection and only one study has shown an association between IL-1B polymorphism and HBV viral load in the development of chronic disease.27 In the present study, we report both promoter SNP (−511T>C) (rs16944) and exon 5 SNP (+3954C>T) (rs1143634) to be associated with a risk of developing chronic hepatitis B.

Pociot et al.42 reported that rs16944 and rs1143634 were correlated with IL-1B expression and that they could influence the protein production. Previous studies have shown that the maximal capacity of cytokine production varies among individuals and correlates with SNP in the promoter region of various cytokine genes.43, 44 IL-1B -511 polymorphism is located at position −511 within the regulatory regions of the gene and has potential functional importance by modulating IL-1 protein production. Hirankarn et al. found that the IL-1B −511C allele were associated with high IL-1B production in the liver, whereas Pociot et al. found that the IL-1B allele T carrier had higher productions of IL-1B than the IL-1B allele C carrier.25, 42

For the +3954C>T polymorphism, Pociot et al. found that individuals homozygous for the T allele produce a fourfold higher amount of IL-1B compared with those displaying the C/C genotype.42

IL-1B -511 gene polymorphism was reported to be associated with the chronic HBV infection in Japanese, Thai, and northeastern Iranian populations; the C/T genotype was more frequent in patients with chronic hepatitis as compared with controls.25, 26, 45 In China, He et al.46 reported that IL-1B −511 polymorphism was associated with chronic hepatitis B infection in the Han population of Southwest China and that the combination of IL-1B −511 and rs9277535 in HLA was the best model to predict chronic HBV infection. A study conducted in Turkey reported a higher frequency of T allele in patients with chronic hepatitis B39 as compared with controls. The influence of −511C/T SNP in the expression of IL-1B gene was suggested, two decades ago, by Pociot et al.42 who reported a significant increase in the expression of IL-1B among −511T homozygous followed by heterozygous individuals. The IL-1B −511 gene may play a role in the chronicity of hepatitis B infection. A study conducted in Thailand showed that the IL-1B −511C allele was associated with the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B patients.25 By contrast, studies conducted in India36, 38 and China33 found no significant difference between patients and controls. Biswas et al.36 reported that, in the Indian population, there was no significant difference in the distribution of genotypes (P = 0.244; OR = 0.78, 95% CI = 0.52–1.18) or allelic frequencies between patients and controls. Another study in India, conducted by Saxena et al.38 revealed no notable difference among HBV carriers and controls. Zhang et al.27 also showed that there was no significant difference in the frequencies of IL-1B alleles or genotypes between patients with chronic hepatitis B and controls in the Chinese population and that the frequencies of the C/C genotype of IL-1B −511, C/T, and T/T in patients with chronic hepatitis B were 23.7%, 49.5%, and 26.8%, respectively, versus 26.1%, 47.4%, and 26.5%, respectively, in controls. These conflicting results are probably due to the various ethnic groups included in the different studies. The frequency of genetic markers in an ethnic population varies from one region to another. It is generally admitted that the presence of a strong genetic diversity among different world communities suggests that the information based on findings in one population should not be used to predict the risk in other populations.

By contrast, in the present study, exon 5 SNP (+3954C>T) (rs1143634) was associated with the risk of developing chronic hepatitis B. A significant dominance of the C/T and T/T genotypes at the +3953 loci in exon 5 was found in 39.8% and 48.3% patients, respectively, and in 46.3% and 35.8% controls, respectively, as compared with the C/C genotype. A Japanese study also reported a higher frequency of T allele26 and an association with an increased risk of Grave's disease (OR = 1.93). However, Fontanini et al.34 found no significant differences between cases and controls in an Italian population and Chen et al.37 reported that the T/T genotype was absent in the Chinese population. This polymorphism was not well studied in the rest of the world.

In Tunisia, only seven studies have been carried out on IL-1B polymorphism47-53 in relation to human diseases including hepatitis C, Grave's disease, and cervical cancer and this is the first study investigating the association between IL-1B and chronic hepatitis B. In our control group, the distribution of C/C, C/T, and T/T genotypes was close to the one found in the control groups of two previous Tunisian studies: Ksiaa Cheikhrouhou et al.,53 in which the distribution was C/C = 40%; C/T = 42%; T/T = 18% for SNP (−511 T>C) and Zidi et al.48 who reported a distribution of C/C = 17%; C/T = 49%; T/T = 34% for exon 5 SNP (+3954C>T). However, the distribution in the control groups of the five other studies47, 49-52 was slightly different; this may be due to the genetic heterogeneity in the Tunisian population, which is characterized by important genetic exchanges throughout history and frequent migrations around the Mediterranean Sea.

When the patients were stratified according to gender, age, or viral load, we did not find any significant difference between patients and controls at position +3954. However, a significant difference was found at position −511 according to viral load and, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that shows a significant association between IL-1B polymorphism and viral load in patients with chronic hepatitis B. The distribution of C/C, C/T, and T/T genotypes in patients with viral load below 2000 IU/ml (35.7%, 44%, and 20.3%) was significantly different from the one in patients with viral load over 2000 IU/ml (31.5%, 25.9%, and 42.6%). Similar to our results, studies from China also found no statistical significance in the distributions of the different genotypes between cases and controls when stratified according to age and gender,35 but significant differences according to viral load were reported in the study of Zhang et al.,27 in which the patients were divided into two subgroups depending on a viral load less or higher than 1000 copies/ml (P = 0.029). In India, a significantly lower viral load was found in the C/C genotype when compared with the C/T and T/T genotypes (P = 0.036 and 0.012, respectively).36

A difference in the susceptibility for HBV infection among individuals has been suggested, which may be due to different expressional levels of the cytokines. Most of these variations result from polymorphisms in the genes encoding these cytokines. IL-1B is a potent inflammatory cytokine involved in many important cellular functions and is an important component of the innate immune response.54

Larger population-based studies involving functional as well as polymorphic aspects, both to confirm our findings and to prospectively assess the role of IL-1B −511 (rs16944) and IL-1B +3954 (rs1143634) polymorphisms in patients with chronic hepatitis B, are still needed. Furthermore, additional details on the demographic data are still required, particularly for the pathologic stage of chronic hepatitis B patients. Persons with HBV infection may have no evidence of liver disease or may have a spectrum of disease ranging from chronic hepatitis to cirrhosis or liver cancer. Determining genetic polymorphisms of mediators that have a role in both the natural course of the infection and the response to treatment and vaccination will contribute significantly to the efficacy of treatment by considering possible risk factors and by the development of new treatment approaches.

A significant role for both the promoter and the exon 5 polymorphisms of IL-1B gene was found in Tunisian patients with chronic HBV infection and, thus, the T allele can be used as a strong disease marker. When the viral load of patients was taken into account, a very highly significant association was found between HBV patients and controls for IL-1B −511.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was partially supported by the Tunisian Ministry for Scientific Research and Technology.

DISCLOSURE

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.