Wound, pressure ulcer, and burn guidelines (2023)―4: Guidelines for the management of connective tissue disease/vasculitis-associated skin ulcers, third edition

This is the secondary publication of the paper that was published in Vol. 134, Iss. 1, pages 1–63, doi: https://doi.org/10.14924/dermatol.134.1 of the Japanese Journal of Dermatology. The authors have obtained permission for secondary publication from the Editor of the Japanese Journal of Dermatology.

| Chapter 1: Guidelines for the management of connective tissue disease/vasculitis-associated skin ulcers (third edition) |

| Chapter 2: Outline of connective tissue disease/vasculitis-associated skin ulcer diagnosis and treatment |

| Chapter 3: Guidelines for the management of connective tissue disease/vasculitis-associated skin ulcers, CQs, and recommendations |

|

|

|

|

| Chapter 4: Definitions of terminology |

| Chapter 5: Explanation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Chapter 6: Details of a systematic review on each CQ |

| List of the members of the Wound, Pressure Ulcer, and Burn Guidelines Drafting Committee |

| COI reporting criteria for participants in the Wound, Pressure Ulcer, and Burn Guidelines Supervising and Drafting Committees, participation/nonparticipation criteria, and a list of the COI disclosed |

1 CHAPTER 1: GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF CONNECTIVE TISSUE DISEASE/VASCULITIS-ASSOCIATED SKIN ULCERS (THIRD EDITION)

1.1 Background to the drafting of guidelines for the management of connective tissue disease/vasculitis-associated skin ulcers (third edition)

Guidelines are “documents systematically prepared to support medical experts and patients for making appropriate judgments in particular clinical situations.” Various clinical departments contribute to the management of connective tissue diseases and vasculitis, but dermatologists play a central role in evaluating skin lesions and treating skin ulcers. The Japanese Dermatological Association prepared these guidelines with an emphasis on the treatment of connective tissue disease– and vasculitis-associated skin ulcers in the clinical setting of dermatology. Such ulcers occur against a background of various types of diseases, typically systemic sclerosis (SSc), but also include systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), dermatomyositis, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), various vasculitides, and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS). Therefore, in preparing the present guidelines, we considered the appropriate diagnostic/therapeutic approach for each of these disorders and developed corresponding algorithms and commentaries. The present guidelines aim to improve the quality and level of connective tissue disease– and vasculitis-associated skin ulcer diagnosis/treatment in Japan by systematically presenting evidence-based recommendations supporting clinical judgments.

1.2 Position of the guidelines for the management of connective tissue disease/vasculitis-associated skin ulcers (third edition)

The Wound, Pressure Ulcer, and Burn Guidelines Drafting Committee was composed of members delegated by the Board of Directors of the Japanese Dermatological Association. It held several meetings and online meetings after the first meeting on June 3, 2018, and has drafted the explanations on wounds in general, and five other related guidelines, including these guidelines, by taking into consideration the opinions of the Scientific Committee and the Board of Directors of the Japanese Dermatological Association. The present guidelines reflect the current standards for diagnosis and treatment of skin ulcers in Japan. Background factors, such as the severity of symptoms and complications, vary among patients with connective tissue disease/vasculitis; therefore, physicians responsible for treatment should decide therapeutic strategies with patients. It is unlikely that the optimized treatment for an individual patient is in absolute agreement with these guidelines. Any deviation from these guidelines should not be the basis for citation in lawsuits or legal disputes. On the other hand, for treatment, the present situation in which treatment guidelines are quoted in lawsuits must be considered.

1.3 Major updated points in the third edition

- To improve transparency, we newly prepared guidelines according to the GRADE approach.

- Clinical question (CQ): A quantitative systematic review (meta-analysis) and qualitative systematic review were performed with respect to four CQs that the Wound, Pressure Ulcer, and Burn Guidelines Drafting Committee members consider the most important.

- To ensure the convenience of the guidelines, an outline of the diagnosis and treatment of connective tissue disease– and vasculitis-associated skin ulcers was divided into general remarks and detailed explanations with respect to diseases. A form to refer to a commentary with respect to the details of important points was adopted.

1.4 Sponsors

All expenses required for drafting these guidelines have been borne by the Japanese Dermatological Association, and no aid or financial support has been provided by organizations, enterprises or pharmaceutical companies.

1.5 Conflicts of interest

According to Japanese Association of Medical Sciences (JAMS) Guidelines on COI Management in Medical Research (https://jams.med.or.jp/guideline/index.html) published by JAMS in March 2017, the members of the guideline-drafting committee disclosed the conflicts of interest (COI) during the past 3 years back to the previous year on assumption as a member and guideline announcement. For reporting: (1) the members' COI, their spouses' COI, (2) first-degree relatives' or income/financial profit-sharing persons' COI, and (3) COI of organizations/divisions to which the members belong were reported with an amount classification using the COI self-disclosure form established in the JAMS Guidelines on COI Management in Medical Research.

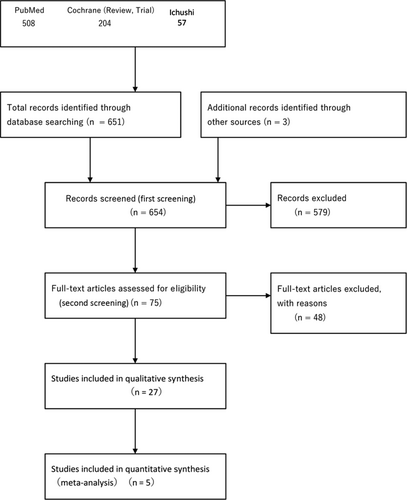

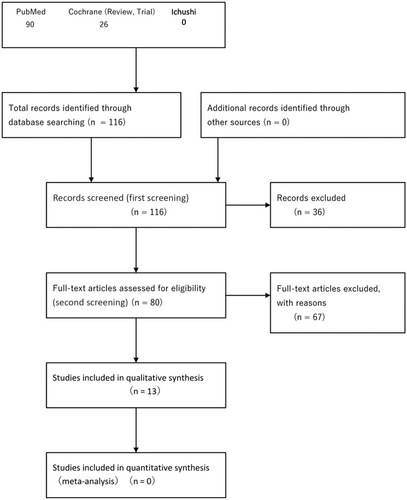

1.6 Collection of evidence

- Databases used: PubMed, Cochrane Library, and Japanese Medical Abstracts Society

- Search period: Between January 1980 and the end of December 2020

1.7 Systematic review methods

According to the Minds Manual for Clinical Practice Guideline Development 2020, accompanying working templates were used.

1.7.1 Evaluation of individual reports (step 1)

Systematic review teams responsible for individual CQs evaluated the bias risk (selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, patient attrition bias, other biases) and indirectness (differences in the study patient population/intervention/comparison/outcome measurement) of each study design (interventional study, observational study) with respect to the outcome-based literature, and extracted the number of patients. When effect-index-presenting methods differed, they were unified to the risk ratio or risk difference, and described as total evidence.

1.7.2 Summary on total evidence (step 2)

The total evidence integrated across outcomes was assessed with respect to a summary on total evidence, and the certainty of evidence was decided on one. The bias risk and indirectness were again evaluated. In addition, inconsistency, inaccuracy, and publication bias were assessed. The certainty (strength) of evidence was classified, as shown in Table 1.

| A (strong) | There is strong confidence in the estimated value of effect |

| B (moderate) | There is moderate confidence in the estimated value of effect |

| C (weak) | Confidence in the estimated value of effect is limited |

| D (very weak) | We are not confident in the estimated value of effect |

1.7.3 Quantitative systematic review (meta-analysis)

When the study design was similar, with the high-degree similarity of each item of PICO (population, intervention, comparison, outcome), a meta-analysis to quantitatively integrate effect indices was performed, and the integrated result was considered as an item for examining the strength of total evidence.

1.7.4 Qualitative systematic review

When it was difficult to perform a quantitative systematic review (meta-analysis), we performed a qualitative systematic review.

1.7.5 Preparation of a systematic review report

The results of the above quantitative or qualitative systematic review were summarized in a systematic review report as the strength of total evidence, and used as materials for preparing recommendations with a summary on total evidence.

1.8 Recommendation-determining methods

1.8.1 Review by persons in charge of each CQ

We prepared a summary of findings, considering the certainty of total evidence regarding outcomes and balance between favorable (advantages) and adverse effects (harm and burden).

The importance (weighting) of favorable and adverse effects was re-evaluated based on the importance of outcomes and certainty of total evidence. The direction and strength of recommendation were comprehensively considered, and submitted to a recommendation decision meeting through discussion by persons in charge of each CQ.

1.8.2 Recommendation decision meeting

- Recommended (strong recommendation)

- Proposed (weak recommendation)

- Not proposed (weak recommendation)

- Not recommended (strong recommendation)

For voting, the Delphi method was adopted. The recommendation level was determined with a consistency of ≥80%. When there was no consistency of ≥80% after three sessions of voting, the result was regarded as “no recommendation.”

Immediately before voting on each CQ, the presence or absence of a COI was reconfirmed, and panel meeting members with a COI did not vote. The results of voting are presented in the explanatory text for each CQ.

1.9 CQ changes in the process of preparation

There was no CQ change in the process of preparation.

1.10 Work for revising the guidelines

The Wound, Pressure Ulcer, and Burn Guidelines Drafting Committee held the First General Guideline Meeting on June 3, 2018, and started the revision. Subsequently, the supervising committee and six guideline-drafting committees held online/mail meetings during the COVID-19 pandemic. The committee for preparing the guidelines for the management of connective tissue disease/vasculitis-associated skin ulcers (third edition) held an online recommendation decision meeting (panel meeting) on February 20, 2022, after a few sessions of mail meetings, and determined the recommendation level. Based on the results, each drafting committee member prepared a draft for the above guidelines, and the present guidelines were prepared through evaluation by the members of the Japanese Dermatological Association.

1.11 Committee for preparing the guidelines for the management of connective tissue disease/vasculitis-associated skin ulcers (third edition)

Refer to the list of drafting committee members.

1.12 Review before publication

Before the publication of these guidelines, opinions were invited from the association members on the homepage of the Japanese Dermatological Association from 2022 to 2023, and necessary revisions were made.

1.13 Promotion of utilization after publication

The present guidelines will be announced at a general meeting of the Japanese Dermatological Association, and published in the Japanese Journal of Dermatology. Furthermore, anyone will be able to download them free of charge on the website of the Japanese Dermatological Association for widespread use. Furthermore, an English version of the guidelines will be published the year after publication.

Committee for preparing the guidelines for the management of connective tissue disease/vasculitis-associated skin ulcers (third edition)

| Name | Belonging to | Apportionment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chairman of the supervising committee | Takao TACHIBANA | Department of Dermatology, Hoshigaoka Medical Center | Supervision |

| Vice-chairman of the supervising committee | Minoru HASEGAWA | Department of Dermatology, University of Fukui | Supervision |

| Vice-chairman of the supervising committee | Manabu FUJIMOTO | Department of Dermatology, Osaka University | Supervision |

| Supervising members | Takeshi NAKANISHI | Department of Dermatology, Meiji University of Integrative Medicine | Supervision |

| Hiroshi FUJIWARA | Department of Dermatology, Niigata University | Supervision | |

| Takeo MAEKAWA | Department of Dermatology, Jichi Medical University Saitama Medical Center | Supervision | |

| Sei-ichiro MOTEGI | Department of Dermatology, Gunma University | Supervision | |

| Yuichiro YOSHINO | Department of Dermatology, Japanese Red Cross Kumamoto Hospital | Supervision | |

| Representative of the drafting committee | Yoshihide ASANO | Department of Dermatology, Tohoku University | Outline/CQ explanation writing, panel meeting |

| Drafting committee | Jun ASAI | Department of Dermatology, Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine | Outline/CQ explanation writing, panel meeting |

| Takayuki ISHII | Department of Dermatology, Toyama Prefectural Central Hospital | Outline/CQ explanation writing, panel meeting | |

| Yohei IWATA | Department of Dermatology, Fujita Health University | Outline/CQ explanation writing, panel meeting | |

| Masanari KODERA | Department of Dermatology, Japan Community Health care Organization (JCHO) Chukyo Hospital | Outline/CQ explanation writing, panel meeting | |

| Chie MIYABE | Department of Dermatology, Tokyo Women's Medical University | Outline/CQ explanation writing, panel meeting | |

| Reiko Omori | Nurse, The University of Tokyo | Panel meeting | |

| Systematic review team | Panel meeting members | ||

| CQ1 | Akihiko UCHIYAMA, Youichi OGAWA, Yuta KOIKE | Jun ASAI, Takayuki ISHII, Yohei IWATA, Masanari KODERA, Chie MIYABE, Reiko Omori | |

| CQ2 | Yorihisa KOTOBUKI, Takuya MIYAGI | Yoshihide ASANO, Jun ASAI, Takayuki ISHII, Yohei IWATA, Masanari KODERA, Chie MIYABE, Reiko Omori | |

| CQ3 | Ken OKAMURA, Yukie YAMAGUCHI, Ayumi YOSHIZAKI | Yoshihide ASANO, Jun ASAI, Takayuki ISHII, Yohei IWATA, Masanari KODERA, Chie MIYABE, Reiko Omori | |

| CQ4 | Mari KISHIBE, Noriki FUJIMOTO | Yoshihide ASANO, Jun ASAI, Takayuki ISHII, Yohei IWATA, Masanari KODERA, Chie MIYABE, Reiko Omori | |

1.14 Plans for revision

The present guidelines are scheduled to be revised in the next 5 years. However, if a partial update becomes necessary, it will be presented on the website of the Japanese Dermatological Association when appropriate.

1.15 Monitoring after announcement

After guideline announcement, the widespread use of the present guidelines and changes in the contents of diagnosis/treatment will be investigated by a questionnaire survey.

1.16 Summary of CQs

CQ1: Are there any drugs effective in preventing or treating SSc-associated skin ulcers?

Prevention

| Recommendation level | Description of recommendation |

|---|---|

|

Bosentan: strong recommendation PDE5 inhibitors: weak recommendation |

The prophylactic administration of bosentan for SSc-associated skin ulcers is recommended. The prophylactic administration of PDE5 inhibitors (sildenafil, tadalafil) for SSc-associated skin ulcers is proposed |

Treatment

| Recommendation level | Description of recommendation |

|---|---|

|

Bosentan: weak recommendation PDE5 inhibitors: weak recommendation |

Treatment with bosentan or PDE5 inhibitors (sildenafil, tadalafil) for SSc-associated skin ulcers is proposed |

CQ2: Are there any treatment methods effective for connective tissue disease–associated calcinosis cutis?

| Recommendation level | Description of recommendation |

|---|---|

| Weak recommendation for all treatments | Treatment with warfarin, diltiazem hydrochloride, colchicine, or bisphosphonate preparations or by surgical resection for connective tissue disease–related calcinosis cutis is proposed. Treatment with rituximab for SSc-related calcinosis cutis is proposed. It is proposed to avoid treatment with rituximab for dermatomyositis-related calcinosis cutis |

CQ3: Are there any drugs effective for vasculitis-associated skin ulcers?

| Recommendation level | Description of recommendation |

|---|---|

| Weak recommendation | Systemic steroid administration is proposed because steroids are routinely used as a base drug for vasculitis-associated skin ulcers in clinical practice, and because their effects have been obtained |

CQ4: Are there any treatment methods effective for rheumatoid vasculitis–associated skin ulcers?

| Recommendation level | Description of recommendation |

|---|---|

| Weak recommendation for all drugs | Treatment with azathioprine in combination with steroids or alone, cyclophosphamide + steroid pulse, TNF-α inhibitors, rituximab, or LCAP (leukocytapheresis)/GCAP (granulocyte and monocyte adsorption apheresis) for rheumatoid vasculitis–related skin ulcers is proposed |

2 CHAPTER 2: OUTLINE OF CONNECTIVE TISSUE DISEASE/VASCULITIS-ASSOCIATED SKIN ULCER DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

2.1 General remarks

2.1.1 Etiological factors for skin ulcers

Various diseases are included in collagen disease/vasculitis that forms skin ulcers, and their causes are diverse. However, some causes, such as circulatory impairment, infection, thrombosis, vasculitis, panniculitis, and calcinosis, are common to each of these diseases. Indeed, skin ulcers are not necessarily caused by one of these disorders alone. Caution is required because multiple factors, such as circulatory impairment plus infection or circulatory impairment plus thrombosis, may be involved. Resolution or elimination of these causative factors is indispensable for controlling skin ulcers. A brief overview of the management of each factor is presented below.

For circulatory disorders, the administration of oral drugs, such as beraprost sodium and sarpogrelate, and intravenous drugs, such as lipoprostaglandin E1 (lipo-PGE1) preparations and argatroban hydrate, is evaluated. For fingertip ulcers due to SSc, warming in a kotatsu (heated table covered by a quilt) is also effective.

For infection, the systemic administration of antibacterial drugs is desirable when the “five signs of infection,” namely redness, swelling, heat, pain, and decreased function, are observed. Concerning topical agents, silver sulfadiazine cream or cadexomer iodine ointment is often used to remove necrotic tissue that has developed due to infection and treat the infection. However, the use of antibacterial drugs on the basis only of the detection of bacteria by culturing of wound samples should be avoided if clinical signs of infection are lacking. The indication for antibacterial drugs should be evaluated by judging whether the condition is due to colonization or infection. At the same time, ulcers due to connective tissue diseases often recur at the same sites, and the detection of infections of scarred wounds is likely delayed. Also, in patients with connective tissue diseases and vasculitis, as corticosteroids (steroids) and immunosuppressants are frequently used to treat the primary disease, attention to increased susceptibility to infection is necessary. Dressing materials are useful when the amount of exudate is high but are inappropriate when the wound is infected, as the ulcer may be exacerbated within a few days between dressing changes.

For thrombosis, the administration of anticoagulants, such as warfarin and various antiplatelet drugs, is necessary. As mentioned above, because thrombi may develop in stagnant blood due to circulatory disturbances or SLE may be concurrent with APS, the possibility of the involvement of multiple causative factors must be considered.

In vasculitis and panniculitis, necrosis of the cutaneous or subcutaneous tissue may occur in active lesions, leading to ulcer formation, or the ulceration of old scarred lesions may be triggered by the infection. For treating active vasculitis-associated skin ulcers, the priority is to control the underlying disease primarily using steroids or immunosuppressants. However, if the skin ulcer is complicated by infection, intensification of the steroid or immunosuppressant therapy may exacerbate the ulcer due to the patient's increased susceptibility to infection. If there are signs of infection, its treatment must be performed simultaneously.

In panniculitis, judging whether the clinical symptoms, such induration and redness/heat, are caused by connective tissue diseases or infection is often difficult. Because blood test data indicate an elevated inflammatory reaction in either case, early differentiation is difficult. The examination of procalcitonin by blood sampling is also useful for confirming infection status because its levels often do not rise even in cases of high connective tissue disease activity. However, attention is required for the possibility of a false-negative result caused by a nonspecific reaction in patients positive for rheumatoid factors and the fact that insurance coverage for procalcitonin measurement is limited to sepsis alone. Although a histopathological examination should be actively considered, it takes time to complete, and antibacterial drugs are often administrated as a diagnostic treatment in the actual clinical setting.

Calcium deposits also often cause ulcer formation if they spontaneously collapse. Regarding calcinosis, oral therapies, such as warfarin therapy, may be considered for treating small lesions, but large calcified lesions are not generally resolved by internal treatment alone and require surgical resection. However, as calcified lesions causing ulceration may extend broadly and occasionally deeply, early resection while the calcium deposits are still small may also be considered depending on treatment invasiveness if the patient responds poorly to internal treatment.

2.1.2 Treatment with topical agents for skin ulcers

- Selection of topical agents for wound bed preparation.

- T: Elimination of necrotic tissue: cadexomer iodine ointment.

- I: Control/elimination of infection: cadexomer iodine ointment, silver sulfadiazine cream, povidone iodine sugar.

-

M: Maintaining a moist environment (control/elimination of exudates):

- when exudates are excessive, cadexomer iodine ointment, dextranomer polymer, povidone iodine sugar;

- when exudates are deficient, silver sulfadiazine cream.

- E: Management of wound margins (resolution/elimination of pockets): no drugs recommended.

-

Selection of topical agents for moist wound healing.

- Wound surfaces with appropriate/deficient exudates: trafermin spray, PGE1 ointment.

- Wound surfaces with deficient exudates: tretinoin tocopherol ointment.

- Wound surfaces with excessive exudates or marked edema: bucladesine sodium ointment.

However, because patients with connective tissue disease/vasculitis-associated skin ulcers often complain of intense pain, the use of topical agents according to these principles is occasionally impossible in cases in which topical agents cause irritating symptoms. The simple protection of the wound using white petrolatum or a petrolatum-based ointment is selected in such cases.

2.1.3 Treatment with dressing materials for skin ulcers

In recent years, occlusive dressings are frequently employed for treating ulcers due to improvements in dressing materials, but a cautious attitude is urged for their use for treating connective tissue disease–associated ulcers. Moist wound healing using an occlusive dressing is expected when wound bed preparation has been achieved and the ulcer condition is improving. However, with connective tissue disease–related ulcers, the condition may change readily in a short period and the ulcers can become exacerbated rapidly over a few days between dressing changes, thus making them worse rather than better. There have been instances of rapid exacerbation in a short period even of improving ulcers in cases of unstable control of the circulatory condition or underlying disease, as well as when the ulcer is infected, as mentioned above. There are also intractable ulcers not expected to heal except by spontaneous separation due to dry gangrene, and an occlusive dressing is inappropriate in such wounds.

2.1.4 Surgical treatment for skin ulcers

Some comments about surgical treatments should also be made. Connective tissue disease–associated ulcers differ from other ulcers in that their condition changes readily depending on primary disease activity. For example, in fingertip ulcers in patients with SSc, wound bed preparation can be achieved by relieving circulatory disturbances and ulcers may be controlled by conservative treatment. On the other hand, circulatory disorders may recur readily at sites of resolved ulcers, resulting in their repeated reactivation. Considering these pathologies, as aggressive surgical treatments, such as finger/toe amputation, may lead to more extensive successive amputations, their indications must be evaluated carefully. Because tissues on the verge of necrosis may be saved by patient repetition of conservative treatments, maximum tissue conservation should also be achieved using debridement unless the tissue is clearly gangrenous. For bedside wound treatment, although the removal of marked necrotic tissue is necessary, the ischemic basement tissue should be preserved whenever possible. Removing marked necrotic tissue without injuring the ischemic tissue of a skin ulcer with forceps can reduce patient pain during wound treatment. When treating connective tissue disease/vasculitis-associated skin ulcers, the patient's unique progress must be considered. Priority should be given to persistent conservative treatments, with surgical therapy progressing from skin grafting to bone curettage (exposure of bone marrow), and, if necessary, to finger/toe amputation, adhering to the principle of conservation or minimally invasive treatment. As a general rule, surgical therapy should be indicated on the condition that the primary disease is adequately controlled, with the exception of infections that require urgent treatment such as necrotizing fasciitis and gas gangrene.

2.1.5 Pain control for skin ulcers

Pain management can also be an issue for connective tissue disease/vasculitis-associated skin ulcers. Acute pain symptoms are often controlled using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or acetaminophen, but caution is needed to prevent kidney and liver function disorders. For intractable pain symptoms, tramadol hydrochloride/acetaminophen, tramadol hydrochloride, and codeine phosphate are the opioids used to manage mild to moderate pain. For patients with highly active conditions and infected skin ulcers, there are also rare cases in which morphine hydrochloride or fentanyl patches (with the requirement of e-learning course completion for their appropriate use) are used as opioids for moderate to intense pain. There are also cases in which inflammation in the blood vessels that nourish the peripheral nerves can cause peripheral neuropathic pain where analgesia using pregabalin, mirogabalin, or duloxetine is effective. A nerve block can also be useful in certain patients.

It is the role of the dermatologist to infer the patient's general condition from skin symptoms, understand the patient's condition through various tests, and perform treatments accordingly. It is our hope that the present guidelines will be useful in the clinical setting.

2.2 Detailed explanation

2.2.1 SSc-associated skin ulcers

SSc exhibits fibrosis of the skin and various organs and vasculopathy as primary manifestations and is a frequent cause of skin ulcers/gangrene in connective tissue diseases. Existing ulcer/gangrene and resulting functional impairments markedly affect patient quality of life (QOL). In patients with SSc, ulcers often develop at the finger/toe tips resulting from peripheral circulatory insufficiency. They are likely to occur on the dorsal aspects of the finger joints accompanying skin sclerosis and flexion contractures. They are also frequently observed at the heel and internal and external malleoli. While ulcers at the finger/toe tips occur more frequently in winter, they are perennial in some patients. Gangrene may develop suddenly. It is not uncommon for small injuries to develop into intractable ulcers, and surgical wounds are no exception. Many patients judged to have sufficient preoperative blood flow experience ulceration of surgical wounds. Ulcers developing due to spontaneous collapse of subcutaneous calcium deposits and those due to infection of corns or their inappropriate treatment (particularly self-treatment) are often encountered. SSc may be complicated by other connective tissue diseases/vasculitis, and attention to APS is necessary. Moreover, as even patients who do not fulfill the diagnostic criteria of SSc (e.g. those who are positive for anticentromere antibody and exhibit Reynaud phenomenon but have no finger/toe sclerosis) may develop ulcers/gangrene, they should be managed without excessive devotion to the diagnostic criteria.

For treating ulcers in SSc patients, it is necessary to keep the affected areas stationary and warm and attempt various combinations of topical and systemic drug therapies while eliminating endogenous and exogenous exacerbating factors. In surgical treatment, because local procedures, such as excessive debridement may enlarge ulcers, sufficient caution is needed. Similarly, finger/toe amputation for gangrene often invites further proximal extension of the wound from the stump. It is extremely important to give priority to conservative treatments and avoid unnecessary surgical stress when treating ulcers/gangrenes of SSc, and waiting for drying and spontaneous separation (autoamputation) of gangrenous tissue is often recommended.

While few individual systemic drug therapies have been shown to be useful for treating ulcers alone, this does not imply that they lack utility. Clinical experience shows that combinations of multiple drugs can be effective. This is also the case with topical treatments, and drugs must be selected according to wound condition. PGE1 ointments and trafermin sprays are frequently used.

Avoiding cold and encouraging rest are also important. In some patients, rapid remission is achieved by changing outpatient care to inpatient care. Pain control of skin ulcers is also important.

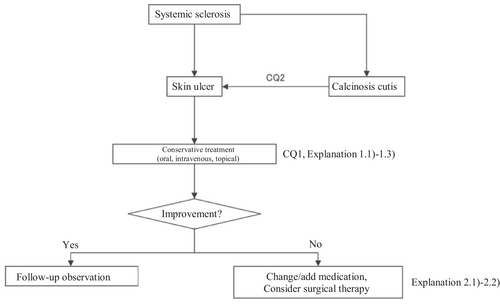

Based on the above concept, an algorithm for SSc-associated skin ulcers (Figure 1) was prepared, and the details are described in CQ1, CQ2, Explanation 1, and Explanation 2.

2.2.2 SLE-associated skin ulcers

SLE exhibits various rashes and occasionally erosion or ulcers. Representative skin manifestations of SLE are as follows: among the diagnostic criteria in Japan are the butterfly rash (malar rash), discoid LE, oral ulcers, and photosensitivity; while those not among the diagnostic criteria include chilblain LE, LE profundus, nodular cutaneous lupus mucinosis, bullous LE, and lupus tumidus. SLE rashes alone are rarely an indication for systemic administration of a steroid or an immunosuppressant and are treated topically. Oral treatment with hydroxychloroquine may also be used. As an exception, the early systemic administration of a steroid is indicated for LE profundus because of the possibility of subsequent scarring or pit formation. Nonspecific skin symptoms observed in SLE include those due to peripheral vascular or circulatory disorders, and skin ulcers or gangrene may appear. Skin biopsy and various blood tests are necessary for their differentiation from exanthema due to APS or vasculitis. Circulation-improving drugs and antiplatelet agents are administrated to treat peripheral vascular and circulatory disorders as needed. If APS or vasculitis has been diagnosed, treatment for these conditions becomes necessary. For details, see the relevant sections of the present guidelines or other guidelines of the Japanese Dermatological Association. In addition, because such patients are often immunocompromised, ulcers can frequently be caused by various infectious diseases, and cases of squamous cell carcinoma forming from scars at intractable ulcers found in discoid LE have been reported.

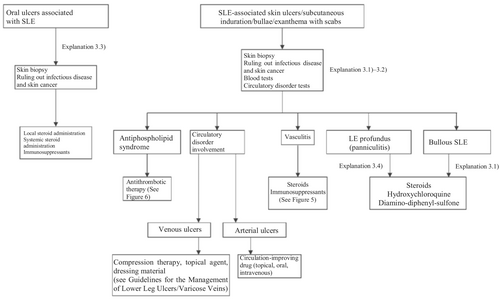

Based on the above concept, an algorithm for SLE-associated skin ulcers and oral ulcers (Figure 2) was prepared, and the details are described in Explanation 3.

2.2.3 Dermatomyositis-associated skin ulcers

Dermatomyositis exhibits various rashes as well as erosion or ulcers. Common cutaneous manifestations occurring with dermatomyositis include Gottron papule (papules affecting the dorsal surfaces of finger joints), Gottron sign, (“keratosis” erythema affecting the dorsal surfaces of limb joints and finger joints), mechanic's hand (keratosis of the ulnar side of the thumb and the radial side of the index/middle fingers), heliotrope rash (reddish purple edematous erythema around the eyelids), facial erythema or edema, scratch dermatitis, poikiloderma, periungual erythema, nailfold bleeding, skin ulcers, calcinosis, and bullae. Causes of erosion and ulcers in dermatomyositis are diverse and include undermining ulcers with necrosis and purpura accompanying angiopathy, shallow secondary skin ulcers or erosion accompanying severe scratch dermatitis, calcinosis cutis, and panniculitis. Treating according to the cause is important.

In recent years, new and highly disease-specific autoantibodies are being discovered for dermatomyositis, and their associations with clinical features have been clarified. Dermatomyositis in which anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (anti-MDA5) antibodies are detected presents as clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis (CADM), in which skin symptoms are typical but there is no clear myopathy, and it is known to accompany rapidly progressing interstitial lung disease at a high incidence. Skin symptoms may include undermining ulcers with purpura and necrosis. On the other hand, dermatomyositis in which anti-transcription intermediary factor 1γ (anti–TIF-1γ) antibodies are detected is known to be associated with a high rate of complications by visceral malignancy. Widespread severe skin inflammation is characteristic, and scratch dermatitis, bullae, erosion, and shallow ulcers often form. Histopathologically, pronounced infiltration of the dermoepidermal junction by inflammatory cells is characteristic. Thus, in the diagnosis and treatment of dermatomyositis-associated ulcers, it is important to fully investigate/evaluate the disease condition according to the form and distribution of ulcers and other cutaneous manifestations. This should also include important complications such as rapidly progressing interstitial lung disease or visceral malignancy. The causes of skin ulcers do not necessarily align with the disease condition of dermatomyositis; thus, ulcer treatment should be considered separate from systemic treatment.

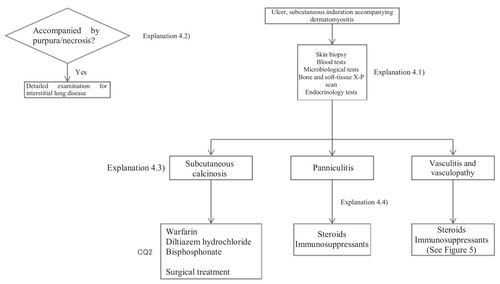

Based on the above concept, an algorithm for dermatomyositis-associated skin ulcers (Figure 3) was prepared, and the details are described in CQ4 and Explanation 4.

2.2.4 Vasculitis-associated skin ulcers

Vasculitis, a group of diseases caused primarily by necrotizing vasculitis observed histopathologically, is often a direct cause of skin ulcers. It is described by the Chapel Hill classification issued in 1994 (commonly called “CHCC 1994”), which was revised in 2012 (commonly called “CHCC 2012,”1 Table 2). In addition to the traditional three size-based categories of large-, medium-, and small-vessel vasculitis, the CHCC 2012 includes a total of seven categories by the addition of variable vessel vasculitis, single-organ vasculitis, vasculitis associated with systemic disease, and vasculitis associated with probable etiology.

| Small-vessel vasculitis |

|

|

| (previous name: Churg–Strauss) |

|

|

|

|

| Medium-vessel vasculitis |

|

| Large-vessel vasculitis |

|

| Variable vessel vasculitis |

|

| Single-organ vasculitis |

|

|

| Vasculitis associated with systemic disease |

|

|

|

| Vasculitis associated with probable etiology |

|

|

|

|

|

| Quoted from Reference (1), partially modified. |

Small-vessel vasculitis includes a total of seven diseases: microscopic polyangiitis, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, and granulomatosis with polyangiitis, which are antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)–related vasculitides; IgA vasculitis; cryoglobulinemic vasculitis; hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis; and anti-glomerular basement membrane disease, in which immune complexes are involved. Medium-vessel vasculitis includes polyarteritis nodosa and Kawasaki disease, while large-vessel vasculitis includes giant cell arteritis and Takayasu arteritis. Of these diseases, the three ANCA-related vasculitides in small-vessel vasculitis, IgA vasculitis, and cryoglobulinemic vasculitis are closely related to skin ulcers as their possible causes. Also notable are polyarteritis nodosa at the medium-vessel level and cutaneous leukocytoclastic angiitis and cutaneous arteritis (corresponding to cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa) among single-organ vasculitides.

In skin ulcers suspected to be due to vasculitis, histopathological findings by skin biopsy are extremely important for the definitive diagnosis. When performing a skin biopsy, the sampling sites should be carefully evaluated; if possible, samples should be obtained from several sites. However, skin ulcer sites are usually densely infiltrated by inflammatory cells including neutrophils; even if necrotizing vasculitis is present, its histological profile is difficult to detect in samples including tissue from the ulcerated area. Moreover, as a skin biopsy may enlarge or exacerbate skin ulcers, caution is necessary.

Meanwhile, livedo reticularis, nodules, infiltration, and tender erythema or purpura are often observed in addition to skin ulcers as skin symptoms of vasculitis. Therefore, in conducting a skin biopsy of the diagnosis of skin ulcers suspected to be due to vasculitis, histological evidence of necrotizing vasculitis is more likely to be obtained by carefully evaluating rashes other than ulcers. Also, if signs of necrotizing vasculitis cannot be detected in conventional skin biopsy specimens, they may be revealed in sections other than those examined. Therefore, it may also be necessary to examine deep-cut sections in certain cases.

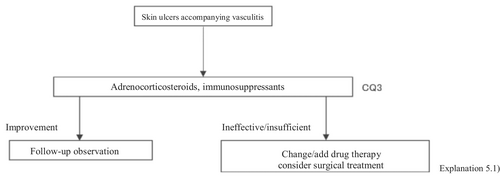

The present guidelines mainly discuss skin ulcers in primary (idiopathic) vasculitis by excluding secondary vasculitis due to cancer, infections, or drugs. The therapeutic algorithm is shown in Figure 4, and the details are described in CQ3 and Explanation 5. In evaluating treatments for skin ulcers due to vasculitis, the manner of controlling the activity of the primary disease is important. While the present guidelines also mention treatments for vasculitis itself, see the “Guidelines for vasculitis and vasculopathy” by the Japanese Dermatological Association2 for details.

2.2.5 RA-associated skin ulcers

Causes of RA-associated skin ulcers are broadly divided into “vasculitic” and “nonvasculitic.” The nonvasculitic skin ulcers can be further classified into “lower leg ulcers due to venous stasis,” “ulcers due to ischemic necrosis of soft tissue associated with compression,” “traumatic ulcers based on skin fragility,” and “other diseases that are likely to complicate rheumatoid arthritis.” Pyoderma gangrenosum is also likely to complicate RA and cause skin ulcers. Therefore, in treating skin ulcers in RA patients, it is important to differentiate among these causes and diseases. Regarding the differentiation procedure, it is important to first definitively differentiate between vasculitic and nonvasculitic ulcers because their treatments differ.

RA-associated vasculitides is collectively called “rheumatoid vasculitis,” which is characterized by the marked diversity of the affected vascular levels compared with other vasculitides (polyarteritis nodosa, IgA vasculitis, granulomatosis polyangiitis, and eosinophilic granulomatosis polyangiitis; Table 2). Thus, rheumatoid vasculitis has characteristics of both necrotic vasculitis of the small arteries in the adipose tissue and leukocytoclastic vasculitis of the small veins in the dermis. (In Japan, RA accompanied by the former is customarily called “malignant rheumatoid arthritis” and the latter is called “rheumatoid vasculitis” in a narrow sense; internationally, all cases of RA-associated vasculitides including both are called “rheumatoid vasculitis.”)

Therefore, its clinical symptoms are diverse, and all kinds of rash suggestive of vasculitis may occur, including subcutaneous nodules, livedo reticularis, skin ulcers, palpable purpura, hemorrhagic blisters, red papules, red nodules, scarlatiniform eruption, macular erythema, purpura, and white atrophy. If such skin symptoms are observed in RA patients, a skin biopsy is essential for the definitive diagnosis, as the accurate identification of the vascular level affected by vasculitis contributes to the selection of appropriate treatments and the determination of the prognosis.

Rheumatoid vasculitis may cause various extraarticular manifestations of RA, such as interstitial pneumonia, gastrointestinal lesions, cardiac lesions, and mononeuritis multiplex, in addition to the cutaneous symptoms. The frequency of the complication of RA by rheumatoid vasculitis is reportedly 0.7% to 5.4%.3-6 Rheumatoid vasculitis is usually observed in a period in which RA activity is enhanced and in patients with a long history of illness (mean illness duration, 10–17 years) such as those with advanced joint destruction. This occurs more frequently in males than in females, as well as in those with high rheumatoid factor levels. Skin symptoms are observed in approximately 75% to 89% of patients with rheumatoid vasculitis,7-12 and they often lead to its diagnosis because they are the initial extraarticular manifestations. Because the prognosis of rheumatoid vasculitis accompanied by systemic symptoms is poor, it is extremely important to invariably perform skin biopsy and ensure early diagnosis and early treatment if suspicious skin lesions are observed.

On the other hand, many of the causes of nonvasculitic skin ulcers are characterized by circulatory disturbances. Even in the absence of vasculitis, many blood vessels are known to degenerate regardless of their size or whether they are arteries or veins in the skin of RA patients, potentially leading to “lower leg ulcers due to venous stasis,” “ulcers due to ischemic necrosis of soft tissue associated with compression” (caused by joint deformity or contracture or inappropriate application of orthoses), and “traumatic ulcers based on skin fragility.”

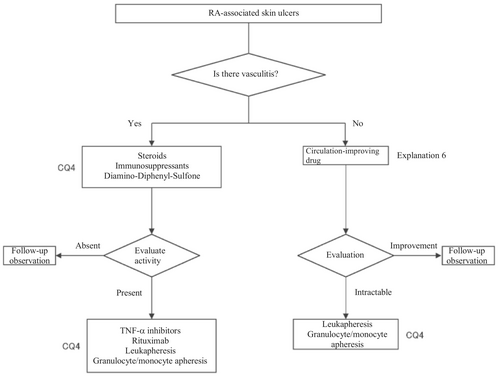

In the present guidelines, a therapeutic algorithm (Figure 5) was prepared for the treatment for RA-associated skin ulcers based on the above considerations, and the details are described in CQ4 and Explanation 6.

2.3 APS-associated skin ulcers

APS is diagnosed when the patient tests positive for antiphospholipid antibodies and develops arterial or venous thrombosis or female infertility. Because arterial or venous thrombosis occurs in the skin and subcutaneous tissue, various skin symptoms develop and intractable skin ulcers frequently form.

Symptoms often observed in APS include arterial or venous thrombosis of the brain, heart, lungs, and limbs; recurrent miscarriage; thrombocytopenia; psychiatric or neurological symptoms, such epilepsy; skin symptoms; eye symptoms such as thrombosis of the central retinal artery or vein; and liver or kidney disorders. Among them, skin lesions are important as the initial manifestations of APS. Frances et al.13 evaluated 200 patients with APS and reported that skin lesions were observed in 31% of patients as the initial manifestations and in 49% throughout the disease course, and that livedo reticularis was the most frequently reported rash (observed in 25% of all patients). Similarly, Cervera et al.14 evaluated 1000 cases of APS and reported that skin lesions were observed as the initial manifestations in 29% and throughout the disease course in 40% of patients, and that livedo reticularis and necrosis due to skin infarction were noted in 24% and 5.5% of patients, respectively. Therefore, as skin lesions are the initial manifestations in many patients with APS, an aggressive examination for the presence or absence of APS should be performed if livedo reticularis or skin ulcers are present even without thrombosis of other organs.

Other cutaneous symptoms of APS reported to date include gangrene, subungual hemorrhage, pyoderma gangrenosum-like rash, fulminant purpura, acrocyanosis, Raynaud phenomenon, Degos disease–like rash, and macular atrophy.15 In addition, reticular purpura observed in the lower leg is not specific to APS but should be differentiated from livedo vasculopathy, polyarteritis nodosa, cutaneous arteritis, cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis, rheumatoid vasculitis, cryoglobulinemic vasculitis, hypergammaglobulinemic purpura, protein C/S deficiency, erythema induratum of Bazin, and syphilis. If livedo reticularis is observed in addition to intractable skin ulcers, the differentiation from the above diseases is difficult based on the clinical profile alone, and the cause must be evaluated by blood tests and histological examinations. While examinations that could risk enlarging the ulcerated surface are typically avoided if there are painful ulcers, a skin biopsy is essential to clarify whether thrombosis or vasculitis is involved in the cause of skin ulcers, and for evaluating the depth and thickness of the affected blood vessels. Because this examination is invasive, it is preferable to collect reliable tissue samples from the epidermis to the adipose tissue in as few attempts as possible, avoiding unnecessary repetition.

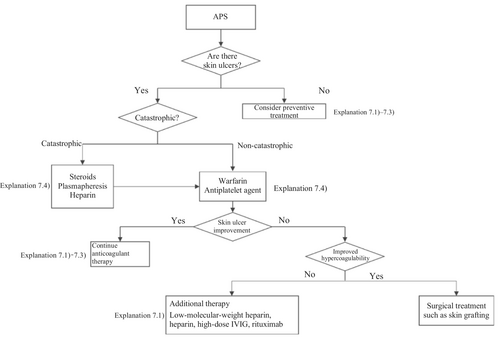

A therapeutic algorithm based on the above principles is shown in Figure 6, and the details are described in Explanation 7. Anticoagulants are the mainstay treatment for APS. The concomitant use of circulation-improving drugs is occasionally effective and worth attempting. Steroid administration may induce hypercoagulability but may also be useful for treating ulcers by suppressing secondary inflammation associated with skin ulcer formation. However, there is no consensus on the use of steroids, and the matter remains open to debate.

Because the control of APS itself is indispensable for treating associated skin ulcers, part of the Guidelines for vasculitis and vasculopathy by the Japanese Dermatological Association,2 MHLW Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (Intractable Disease Policy Research Project) for Research on Intractable Vasculitis Guidance for treatment of APS, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, polyarteritis nodosa, and rheumatoid vasculitis 202016 was cited in the compilation of the present guidelines.

3 CHAPTER 3: GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF CONNECTIVE TISSUE DISEASE/VASCULITIS-ASSOCIATED SKIN ULCERS, CQS, AND RECOMMENDATIONS

CQ1: Are there any drugs effective in preventing or treating SSc-associated skin ulcers?

| Recommendation level | Description of recommendation | Results of voting | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevention |

Bosentan: Strong recommendation PDE5 inhibitors: weak recommendation |

The prophylactic administration of bosentan for SSc-associated skin ulcers is recommended. The prophylactic administration of PDE5 inhibitors (sildenafil, tadalafil) for SSc-associated skin ulcers is proposed |

Bosentan: strong recommendation 6/6 PDE5 inhibitors: weak recommendation 6/6 |

| Treatment |

Bosentan: weak recommendation PDE5 inhibitors: weak recommendation |

Treatment with bosentan or PDE5 inhibitors (sildenafil, tadalafil) for SSc-associated skin ulcers is proposed. |

Bosentan: weak recommendation 6/6 PDE5 inhibitors: weak recommendation 6/6 |

3.1 Background/purpose

SSc induces fibrosis of the skin and various organs such as the lung/esophagus/intestinal tract/kidney. Concerning its pathogenesis, 3 factors are recognized: immune dysfunction, vascular damage, and fibrosis are primarily known, but vascular damage may play a key role in the onset of skin ulcers. Skin ulcers occur through persistent dermal ischemia related to microcirculatory disorder at the distal portions of the extremities such as the fingertips. Therefore, drugs that reduce vascular damage are selected as treatment options. Furthermore, in addition to skin ulcers, Raynaud phenomenon is observed as a representative symptom of vascular damage. This phenomenon refers to transient ischemia of the fingers related to reversible arterial spasm. Vasoconstrictors, such as endothelin, and cold stimulation–related sympatheticotonia, are complexly involved in the pathogenesis of this phenomenon. From the viewpoint of a similar pathogenesis, drugs that relieve Raynaud phenomenon are also regarded as candidates for treatment. Concretely, these include vasodilators, antiplatelet drugs, drugs for pulmonary hypertension, calcium antagonists, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, and statins. In the present guidelines, these treatment options were examined using the evidence-based method (EBM) method. In addition, SSc-associated skin ulcers are often refractory and can induce severe pain. Recurrent ulcers and shortening of the distal portions of the extremities may significantly affect the patient's QOL. From these viewpoints, the prevention of new skin ulcers is an important clinical issue, and drugs that prevent their onset were also investigated.

3.2 Scientific basis

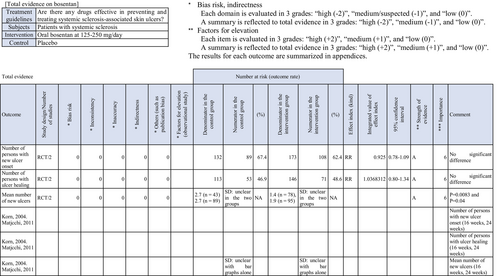

To investigate drugs effective in preventing and treating skin ulcers in patients with SSc, randomized controlled trials (RCT) on “the prevention of new skin ulcers” and “healing of skin ulcers that had existed” were extracted, and 26 reports corresponded to them. Of these, bosentan and PDE5 inhibitors (sildenafil, tadalafil), of which quantitative systematic reviews had been performed, were adopted for this CQ.

Two RCTs18 showed that an endothelin receptor antagonist, bosentan, prevented the onset of new skin ulcers. In addition, a meta-analysis19 reported its preventive effects on the onset of new skin ulcers. Thus, the recommendation level for prevention is strong. On the other hand, these RCTs did not show any significant difference in the curative effects on skin ulcers. There was no other drug with a high level of evidence on skin ulcer healing. We decided to propose treatment with bosentan through a review at a panel meeting, considering the publication of many case series studies of bosentan20, 21 and widespread clinical use of this drug for the treatment of refractory SSc-associated skin ulcers in Japan. As there is no evidence exceeding the case series studies, the strength of total evidence is D (very weak), and the recommendation level is weak.

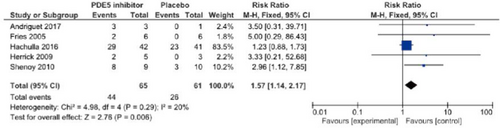

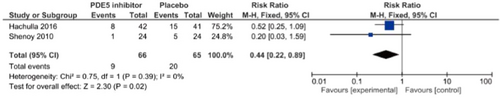

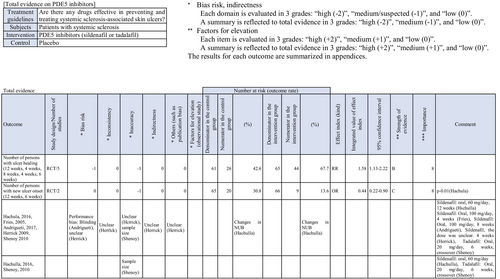

Concerning PDE5 inhibitors, there is one RCT of sildenafil22 showing a tendency to prevent the onset of new skin ulcers. Furthermore, one RCT of tadalafil23 showed that the number of patients with new ulcer onset was smaller than in the placebo group. Based on these results, the recommendation level for prevention is weak. With respect to therapeutic effects, one RCT of sildenafil demonstrated its therapeutic effects, and one RCT of tadalafil also showed its therapeutic effects on skin ulcers. The present guidelines drafting committee uniquely performed a meta-analysis of these reports. Significant therapeutic effects on skin ulcers were observed. Considering a bias for these, the recommendation level for treatment is weak.

3.3 Commentary

Concerning the usefulness of the endothelin receptor antagonist bosentan, Korn et al.17 performed an RCT in 122 patients with SSc. In the bosentan group, the mean number of new ulcers was significantly inhibited in comparison with the placebo group. In addition, another RCT in 188 patients (Matucci-Cerinic et al.18) showed a similar result. Tingey et al.19 performed a meta-analysis of these RCTs and found the significant preventive effects of bosentan on new skin ulcers. In these RCTs, the therapeutic effects of bosentan on skin ulcers were not significant. On the other hand, Garcia et al.20 administered bosentan to 15 SSc patients with skin ulcers in a case series study, and confirmed a significant decrease in the number of skin ulcers, with a mean follow-up of 24.7 months. Furthermore, a study reported the usefulness of this drug for treating skin ulcers other than digital ulcers.21 Concerning another endothelin receptor antagonist, macitentan, there is one RCT by Khanna et al.24 There was no significant difference in its preventive effects on the onset of new skin ulcers. However, in this trial, the incidence of new skin ulcers in the placebo group was lower than in other studies, and this may have contributed to the finding that there was no significant difference.

Concerning the PDE5 inhibitor sildenafil, Hachulla et al.22 performed an RCT in 83 patients with SSc-associated skin ulcers (n = 192), and reported that the number of patients who developed new skin ulcers in the sildenafil group was slightly smaller than in the placebo group. Furthermore, sildenafil administration significantly decreased the mean number of skin ulcers. Shenoy et al.23 performed a crossover RCT of another PDE5 inhibitor, tadalafil, in 24 patients, and found that the results for the onset of new skin ulcers and skin ulcer healing were significantly better than in the placebo group. A meta-analysis regarding the therapeutic effects of PDE5 inhibitors (sildenafil, tadalafil) on skin ulcers by Tingey et al.19 showed significant increases in the number of patients in whom the administration of PDE5 inhibitors reduced skin ulcers and the number of patients in whom healing was achieved. In the present guidelines, a meta-analysis of a report from Hachulla et al.22 and four RCTs25-27 was uniquely performed with respect to skin ulcer healing. As a result, significant effects on skin ulcer healing as an outcome (relative risk [RR], 1.57 [95% CI, 1.14–2.17], Z = 2.76; p = 0.006) were observed in the PDE5 inhibitor–treated group. However, the number of meta-analysis patients was approximately 60, and there may be a publication bias; thus, the strength of total evidence is B (middle), and the recommendation level is weak. Furthermore, a unique meta-analysis regarding the preventive effects of PDE5 inhibitors on skin ulcers was performed based on reports from Hachulla et al.22 and Shenoy et al.,23 establishing the onset of new skin ulcers as an outcome. As a result, the onset of skin ulcers was significantly prevented in the PDE5 inhibitor–treated group (RR, 0.44 [95% CI, 0.22–0.89], Z = 2.30; p = 0.02). Considering the number of patients (approximately 60) and a publication bias, the strength of total evidence is B (middle), and the recommendation level is weak.

Regarding the following drugs, we concluded that RCTs did not confirm their preventive or curative effects on the onset of new skin ulcers or that the level of evidence from RCTs was low: beraprost sodium, lipo-PGE1 preparations, nifedipine, atorvastatin, iloprost, udenafil, quinapril, cyclophosphamide, selexipag, treprostinil, botulinum toxin, and riociguat.

However, in clinical practice, prostaglandin preparations, calcium antagonists, and antiplatelet drugs have been empirically used for the treatment of SSc-associated skin ulcers. In particular, many studies reported their usefulness for treating Raynaud phenomenon as a vascular lesion.28-30 Combination therapy with these drugs is also considered for the prevention and treatment of SSc-associated skin ulcers in clinical practice (refer to Explanation 1, Chapter 5).

Furthermore, caution is needed for the use of ACE inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor antagonists. With respect to the effects of the former on vascular lesions, an RCT with quinapril showed that there was no improvement in the frequency or severity of Raynaud phenomenon, and that new skin ulcer onset was not inhibited.31 Concerning angiotensin II receptor antagonists, a comparative study of losartan potassium with nifedipine for Raynaud phenomenon was performed. There were slight improvements in the frequency and severity of Raynaud phenomenon in patients with SSc, but they were not significant. The two drugs did not significantly ameliorate Raynaud phenomenon as a vascular lesion.32 In addition, ACE inhibitors are effective for scleroderma renal crisis, but their usefulness in prophylactic administration remains to be clarified.31, 33 Furthermore, a recent large-scale, prospective cohort study in Europe showed that the administration of ACE inhibitors rather increased the risk of scleroderma renal crisis.34 Based on these findings, if other drugs are available, the introduction of ACE inhibitors only for the prevention and treatment of skin ulcers should be carefully examined.

3.4 Precautions for clinical use

Among the recommended drugs, bosentan administration for preventing the onset of new skin ulcers is covered by health insurance. As an adverse reaction, the incidence of liver dysfunction is high, and there are serious cases; therefore, caution is required. On the other hand, bosentan administration for treating skin ulcers is not covered by health insurance. PDE5 inhibitors are covered by health insurance only for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Therefore, whether the recommended drugs are indicated must be carefully considered.

3.5 Possibility of future research

There are many articles describing the usefulness of calcium antagonists for treating SSc-related Raynaud phenomenon30, 35 These agents may reduce peripheral circulatory disorder. On the other hand, there is only one RCT on the prevention of new skin ulcer onset and healing.36 No RCT of which the evidence level is high has been performed. Calcium antagonists may be useful for preventing the onset of new skin ulcers and achieving skin ulcer healing in patients with SSc, but may this has not been sufficiently evaluated. As they are frequently used in clinical practice, evidence should be established in the future. Concerning botulinum, there is one RCT each on botulinum toxin type A/B with respect to the prevention of new skin ulcer onset and healing.37, 38 Botulinum toxin type B was confirmed to inhibit the onset of new skin ulcers and promote skin ulcer healing. Currently, it is not covered by health insurance, but its effects should be demonstrated by accumulating cases in the future as a remedy from Japan.

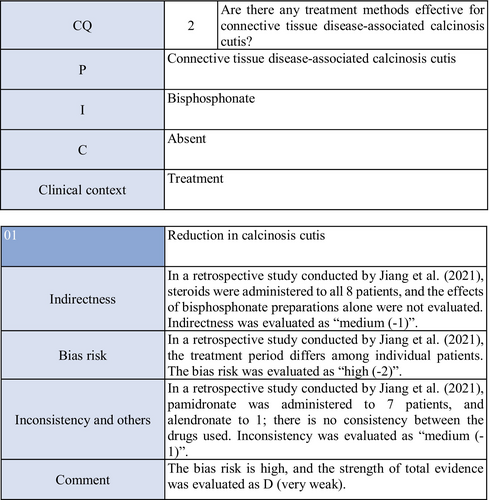

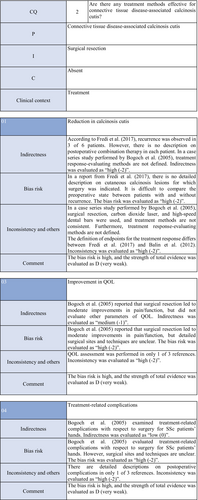

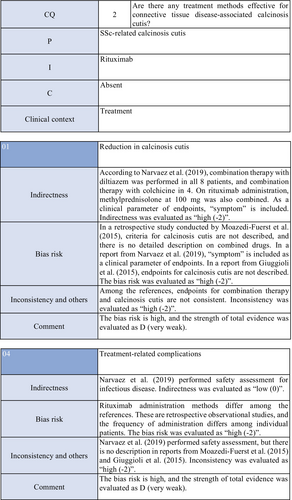

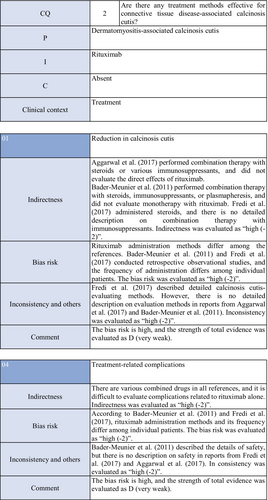

CQ2: Are there any treatment methods effective for connective tissue disease–associated calcinosis cutis?

| Recommendation level | Description of recommendation | Results of voting |

|---|---|---|

| Weak recommendation for all treatments | Treatment with warfarin, diltiazem hydrochloride, colchicine, or bisphosphonate preparations or by surgical resection for connective tissue disease–related calcinosis cutis is proposed. Treatment with rituximab for SSc-related calcinosis cutis is proposed. It is proposed to avoid treatment with rituximab for dermatomyositis-related calcinosis cutis |

Warfarin: Connective tissue disease, weak recommendation 7/7 Diltiazem hydrochloride: connective tissue disease, weak recommendation 7/7 Colchicine: connective tissue disease, weak recommendation 7/7 Bisphosphonate preparations: connective tissue disease, weak recommendation 7/7 Surgical resection: connective tissue disease, weak recommendation 7/7 Rituximab: SSc, weak recommendation 7/7 Dermatomyositis: weak recommendation 7/7 |

3.6 Background/purpose

In patients with connective tissue disease, dermal to subcutaneous calcinosis is often observed. Among various types of connective tissue diseases, calcinosis is most commonly induced by SSc (18%–49%) and dermatomyositis (in adults: ≤30%, in children: 30%–70%).39-48 Calcinosis cutis often causes ulceration through bacterial infection–related secondary infection or self-destruction. Furthermore, calcinosis may induce pain, leading to a limitation in the range of motion and muscle atrophy. For skin ulcers that follow calcinosis, general drugs for skin ulcers alone are not effective, and calcification-targeting treatment is necessary. In clinical practice, various drugs, including warfarin and diltiazem hydrochloride, are used to treat small, calcified lesions. Furthermore, surgical resection is sometimes considered for large, extensive calcified lesions, considering invasiveness. Therefore, the treatment of calcinosis cutis with pain or ulceration is clinically an important issue, and we aim to examine the effects of each treatment method on connective tissue disease–related calcification using the EBM method and present the directivity of treatment.

3.7 Scientific basis

To verify drugs effective in reducing and inhibiting connective tissue disease–related calcinosis, a literature search on various treatment methods was performed. With respect to treatment methods (warfarin, diltiazem hydrochloride, colchicine, bisphosphonate preparations, surgical resection, rituximab) with evidence above case series studies for SSc and dermatomyositis among various types of connective tissue disease, the literature was adopted, and the recommendation level was described.

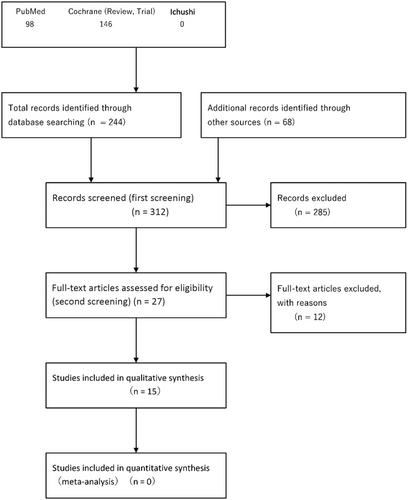

The literature review consisted of: warfarin (one RCT,49 two case series studies),50, 51 diltiazem hydrochloride (two cohort studies,52, 53 two case series studies),54, 55 colchicine (two cohort studies),52, 53 bisphosphonate preparations (one cohort study),55 surgical resection (two cohort studies,52, 53 one case series study),56 rituximab (SSc, three case series studies),57-59 and dermatomyositis (one RCT,60 one cohort study,52 one case series study).61

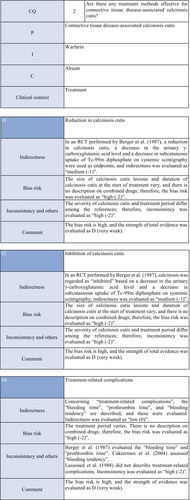

3.8 Commentary

Warfarin inhibits a vitamin K–dependent enzyme that converts glutamic acid to γ-carboxyglutamic acid in the process of calcification; it may have anticalcification actions.62 Concerning the effects of warfarin on calcinosis cutis, there is one RCT49 and two case series studies.50, 51 Berger et al.49 performed a pilot study in four patients with connective tissue disease and calcinosis cutis, including two with dermatomyositis and one with overlap syndrome consisting of dermatomyositis/SSc, to examine the effects of low-dose (1 mg/day) warfarin administration for 18 months. As a result, there was a decrease in the urinary γ-carboxyglutamic acid level in two patients, and systemic scintigraphy showed a decrease in subcutaneous uptake of Tc-99m diphosphate. In one patient, there was a decrease in the number of calcified lesions. Subsequently, four patients were newly added, and the effects of low-dose (1 mg/day) warfarin were investigated for 18 months in a total of eight patients. One patient dropped out of the study because of poor compliance, and the study was continued in the other seven patients. Although there were no changes in calcified lesions, there was a decrease in Tc-99m diphosphate uptake on systemic scintigraphy in two-thirds of the patients in the warfarin-treated group. In the placebo group, there was no decrease in Tc-99m diphosphate uptake. As there was no influence on the bleeding time or prothrombin time, it was concluded that warfarin was useful for inhibiting the progression of calcification. Furthermore, Cukierman et al.50 administered low-dose (1 mg/day) warfarin to three patients with SSc for 1 year to treat calcified lesions and found that calcified lesions measuring ≤2 cm were ameliorated, with no adverse reactions such as bleeding tendency. On the other hand, Lassoued et al.51 administered 1 mg/day of warfarin to six patients with prolonged calcinosis (five with dermatomyositis and one with SSc) for 1 year and reported its ineffectiveness. For the following reasons, the strength of total evidence is D (very weak) and the recommendation level is weak. The two studies were observational and the RCT had a bias risk (−1).

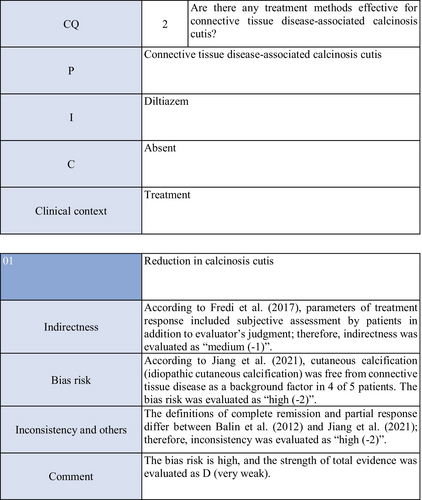

Diltiazem hydrochloride may prevent calcinosis by inhibiting intracellular calcium ion influx. There are four case reports showing its effectiveness in treating calcification in patients with dermatomyositis63-65 or SSc.66 In addition, there are two cohort studies52, 53 and two case series studies54, 55 that provide further evidence. Fredi et al.52 performed a retrospective cohort study in 74 patients (30 with polymyositis, 30 with dermatomyositis, 13 with overlap syndrome, one with sporadic inclusion body myositis), and reported that diltiazem hydrochloride had been administered to seven of 16 patients with calcification, whereas there was no treatment response. Balin et al.53 performed a retrospective cohort study in 78 connective tissue disease patients with calcification. Of 14 diltiazem hydrochloride–treated patients in whom it was possible to evaluate the treatment response, there was no response in five and a partial response was achieved in nine. Vayssarirat et al.46 performed a case series study, and investigated the effects of diltiazem hydrochloride at 180 mg/day on SSc-related calcified lesions. In three of 12 patients with SSc in whom image-based assessment was possible, a slight improvement was achieved. Palmieri et al.54 administered diltiazem hydrochloride at 240 to 480 mg/day to four patients with idiopathic calcification and one with CREST syndrome, and reported improvements in all patients. As these were observational studies, the strength of total evidence is D (very weak), and the recommendation level is weak.

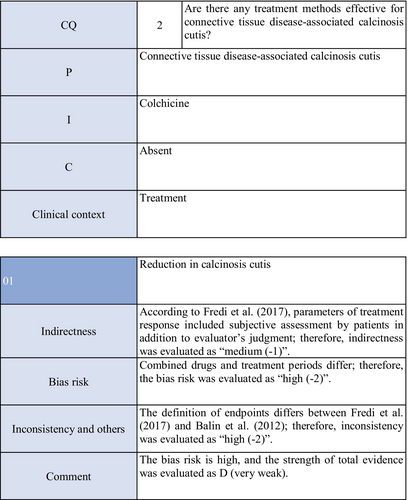

Colchicine may exhibit anticalcification actions by inhibiting leukocyte migration. Concerning the effects of colchicine on calcinosis cutis, there are two cohort studies.52, 53 Fredi et al.52 performed a retrospective cohort study and reported its effectiveness in one of nine patients. In another retrospective cohort study by Balin et al.,53 remission was achieved in one of seven patients, there was no response in four, and a partial response was achieved in two. As these were observational studies, the strength of total evidence is D (very weak), and the recommendation level is weak.

Concerning the effects of bisphosphonate preparations on calcinosis cutis, there is one cohort study.55 According to the study, treatment with bisphosphonate preparations in eight adult dermatomyositis patients with calcification resulted in remission in two, whereas there was no response in six. Thus, the strength of total evidence is D (very weak), and the recommendation level is weak.

Regarding the effects of surgical resection on calcinosis cutis, there are two retrospective cohort studies52, 53 and one case series study.56 Fredi et al.52 performed a retrospective cohort study in 74 patients (30 with polymyositis, 30 with dermatomyositis, 13 with overlap syndrome, one with sporadic inclusion body myositis). Of six patients who underwent surgical resection, it was effective in three. Balin et al.53 performed a retrospective cohort study in 78 connective tissue disease patients with calcified lesions (30 with dermatomyositis, 24 with SSc, six with overlap syndrome, four with mixed connective tissue disease, four with lupus panniculitis, two with SLE, one with RA, one with polymyositis, six with undifferentiated connective tissue disease). In 28 patients, surgery was performed, leading to “remission” in 22, “partial improvement” in five, and “no change” in one. They reported that surgery was useful for treating large, extensive, symptomatic calcified lesions. Bogoch et al.56 reviewed 34 articles in a case series study on surgery for the hands of patients with SSc, and reported that surgical resection reduced moderate pain, improving function. However, they reported the necessity of extended resection, a poor peripheral circulation–related delay in wound healing, necrosis, and possibility of a necrosis-related limitation in the range of motion. Thus, the strength of total evidence is D (very weak), and the recommendation level is weak.

Concerning the effects of rituximab on calcinosis cutis, there are three case series studies in patients with SSc.57-59 Moazedi-Fuerst et al.57 reported the disappearance of calcification in all three patients. Narvaez et al.58 observed “complete remission” in two of eight patients, “partial response” in two, and “no response” in four. Giuggioli et al.59 reported that three of six patients responded. As these were case series studies, the strength of total evidence is D (very weak), and the recommendation level is weak.

On the other hand, concerning dermatomyositis, there is one RCT,60 one cohort study,52 and one case series study.61 Aggarwal et al.60 administered rituximab to 120 patients with dermatomyositis (72 adults [seven with calcinosis], 48 young patients [22 with calcinosis]), and reported its effects on dermal lesions. As an item for evaluating the effects, they adopted calcinosis, but suggested that rituximab was ineffective. Bader-Meunier et al.61 administered rituximab to nine patients with juvenile dermatomyositis (six with calcinosis), and reported that it was ineffective for calcinosis, whereas it was effective for dermal/muscular lesions to some extent. Fredi et al.52 administered this drug to two patients with dermatomyositis, and reported that one patient responded. As the RCT by Aggarwal et al. has a bias risk (−1), the strength of total evidence is D (very weak), and the recommendation level is weak.

3.9 Precautions for clinical use

In the literature adopted in this CQ, there are many cases in which combination therapy for connective tissue disease was selected or in which various treatments had been performed. For this reason, it was difficult to verify the efficacy of individual drugs. Furthermore, many clinical studies that we adopted examined the efficacy for organ lesions other than calcinosis lesions; therefore, the number of patients was small to investigate the efficacy for calcified lesions, and statistical analysis was impossible. Briefly, the evidence level of all treatments is low, and attention must be paid to adverse reactions to the respective drugs when selecting treatment. In clinical practice, recommended drugs, such as warfarin and diltiazem hydrochloride, should be sequentially selected for small calcified lesions. Surgical resection should be considered for large, extensive calcified lesions, considering invasiveness. However, surgical treatment is associated with some risks, such as a delay in wound healing, secondary infection, and pain, and should be performed in patients in whom the advantage of treatment may exceed its disadvantage. Furthermore, it is necessary to consider that the condition may often recur even if these treatments are performed.

In this CQ, the recommendation level is not described, but case series or cohort studies suggested the efficacy of some drugs for dermatomyositis- or SSc-related calcinosis lesions. Concerning SSc, there is a case series study demonstrating the efficacy of minocycline. Robertson et al.67 administered 50 to 100 mg/day of minocycline to nine limited cutaneous SSc patients with calcified lesions, and reported that a partial response was achieved in eight patients. In dermatomyositis, anti–tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) preparations,68 intravenous immunoglobulin therapy,52, 69 and intravenous cyclophosphamide therapy70 have been reported. Campanilho-Marques et al.68 performed a cohort study regarding the efficacy of anti–TNF-α preparations in 60 patients with childhood dermatomyositis, and reported their efficacy in 15 (54%) of 28 patients with calcified lesions and disappearance in eight (29%). For intravenous immunoglobulin therapy, there are two retrospective cohort studies.52, 69 Galimberti et al.69 found a partial response in five of eight patients with dermatomyositis. Fredi et al.52 reported that an improvement was achieved in one of seven patients. Overall, the efficacy of this therapy was demonstrated in six of 15 patients with dermatomyositis; it may be effective, although the evidence level is not high. Moraitis et al.70 performed a cohort study of intravenous cyclophosphamide therapy for severe childhood dermatomyositis, and reported that calcified lesions were reduced in nine of 14 patients.

3.10 Possibility of future research

Currently, there are no high-quality RCTs establishing calcinosis as a primary outcome. There are only two studies (one RCT of warfarin in a small number of patients49 and one RCT of rituximab) establishing calcinosis as a secondary endpoint.60 In other case series or cohort studies, there is no sufficient description on the size of calcinosis lesions, severity, period, or pain, and subgroup analysis was not performed. In patients with connective tissue disease, calcinosis treatment is an important unmet needs. In the future, a high-quality intervention study should be performed.

CQ3: Are there any drugs effective for vasculitis-associated skin ulcers?

| Recommendation level | Description of recommendation | Results of voting |

|---|---|---|

| Weak recommendation | Systemic steroid administration is proposed because steroids are routinely used as a base drug for vasculitis-associated skin ulcers in clinical practice, and because their effects have been obtained | Systemic steroid administration: Weak recommendation 7/7 |

3.11 Background/purpose

Vasculitis refers to a disease in which the vascular structure is damaged through immune cell infiltration in the vascular wall, inducing ischemia-related tissue/organ disorder. The pathogenesis of vasculitis remains to be clarified. Diagnosis/treatment methods have not been sufficiently established. In the Chapel Hill classification71 published in 1994, the classification of vasculitis based on vascular thickness (large, medium, and small blood vessels) was proposed. In a revision in 2012,1 it was subdivided in consideration of the etiology and underlying disease. In addition, the Nomenclature of Cutaneous Vasculitis: Dermatological Addendum to the CHCC 201272 was published in 2018, providing a detailed description of individual skin lesions associated with vasculitis. In the skin, the incidence of medium/small vessel vasculitis is high. Cutaneous vasculitis induces various dermal symptoms, but skin ulcers may occur.

For the treatment of vasculitis-associated skin ulcers, it is the most important to control primary disease activity. However, there are cases in which it is difficult to evaluate which treatment is useful for treating skin ulcers, especially when physicians other than dermatologists are responsible for treatment. In this section, we establish the CQ “Are there any drugs effective for vasculitis-associated skin ulcers?” and aim to present the directivity of treatment for vasculitis-related skin ulcers based on the literature previously reported.

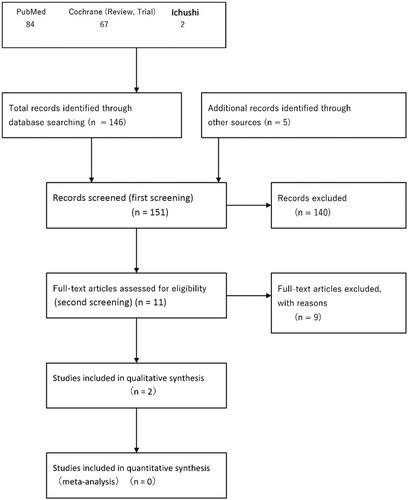

3.12 Scientific basis

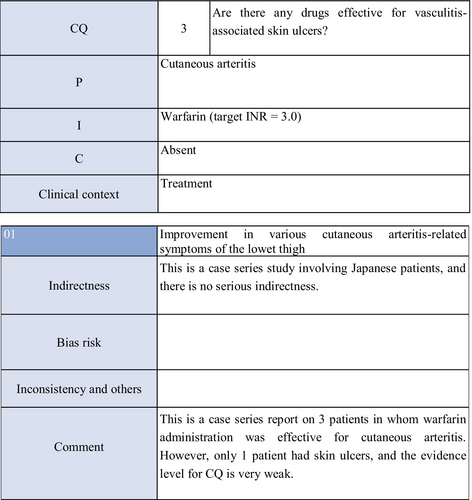

Systemic steroid administration is inexpensive, effective, and fast-acting; therefore, it is ranked as a first-choice drug for the treatment of vasculitis-associated skin ulcers,73 and routinely used. According to a study presented by Daoud et al.,74 in which 39 patients with cutaneous arteritis (conventionally termed “cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa”) with skin ulcers and 40 without skin ulcers were retrospectively investigated, the duration of disease was slightly prolonged in the former, and the incidence of concomitant neuropathy was high. Furthermore, prednisolone administration at 60 to 80 mg/day reduced pain, subcutaneous nodes, and skin ulcers in most patients with skin ulcers, but dose reduction led to recurrence in most patients. Combination therapy with immunosuppressants was attempted. Kumar et al.75 reported eight patients with childhood cutaneous arteritis and terminal gangrenes. Systemic steroid administration resulted in remission in all patients, but recurrence was noted in four patients and spontaneous falling of the fingers or toes in six, leading to amputation of the right leg in one patient. In addition, there are many case reports on polyarteritis nodosa,76 eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis,77 and granulomatosis with polyangiitis78 in which a combination of systemic steroid administration and immunosuppressants reduced skin ulcers.

3.13 Commentary

Although high-level evidence in the literature is limited, as noted above, systemic steroid administration is routinely selected as a base remedy for vasculitis-associated skin ulcers in clinical practice, and its effects have been reported. We considered it useful, but the recommendation level is weak.

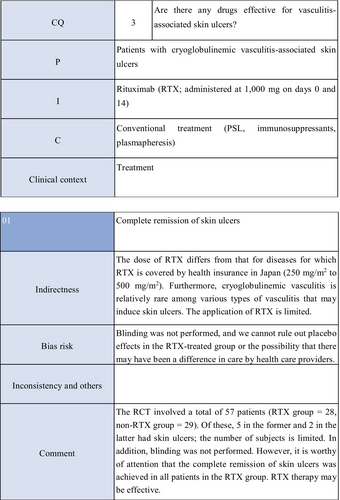

Other drugs include cyclophophamide, rituximab, methotrexate, azathioprine, and intravenous immunoglobulin. Cyclophophamide is routinely used for remission induction and maintenance therapies in patients with polyarteritis nodosa, ANCA-associated vasculitis, or giant cell arteritis. Many studies have reported on the therapeutic effects of combination therapy with systemic steroid administration for vasculitis-associated skin ulcers.78-88 Rituximab was shown to be as effective as cyclophosphamide in performing remission induction therapy for ANCA-associated vasculitis.89 Its usefulness for treating skin ulcers related to ANCA-associated vasculitis has been reported.90-92 In an RCT in 57 patients with cryoglobulinemic vasculitis,93 rituximab administration led to the remission of skin ulcers in all five patients with skin ulcers. Concerning methotrexate, there are case reports showing its efficacy for steroid-resistant polyarteritis nodosa–associated skin ulcers.94, 95 Several studies reported the efficacy of azathioprine in combination with systemic steroid administration for cutaneous arteritis– or polyarteritis nodosa–associated skin ulcers.76, 96 Concerning intravenous immunoglobulin therapy, there are case reports demonstrating its effectiveness for skin ulcers associated with refractory polyarteritis nodosa or granulomatosis with polyangiitis.79, 97, 98 Thus, systemic steroid administration or immunosuppressive therapy for vasculitis control may also be useful for treating vasculitis-associated skin ulcers. However, with respect to individual drugs, there are few articles of which the evidence level is high, and they should be further examined in the future.

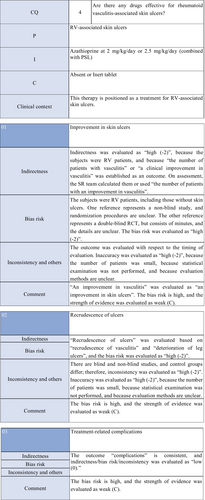

3.14 Precautions for clinical use