2020 guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous pruritus

Takahiro Satoh: Cutaneous Pruritus Clinical Guidelines Planning Chair.

This is the secondary English version of the original Japanese manuscript for “2020 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Cutaneous Pruritus” published in the Japanese Journal of Dermatology 130(7); 1589–1606, 2020.

Abstract

The mechanisms underlying itch are not fully understood. Physicians usually encounter difficulty controlling itch in generalized pruritus. Since only a small percentage of patients with generalized pruritus respond to antihistamines (H1 receptor antagonists), a variety of itch mediators and mechanisms other than histaminergic signals are considered to be involved in itch for these non-responsive patients. In 2012, we created guidelines for generalized pruritus. Those guidelines have been updated and revised to make some of the definitions, diagnostic terms, and classifications more applicable to daily clinical practice. Cutaneous pruritus as designated in these guidelines is a disease characterized by itch without an observable rash. Generalized pruritus (without skin inflammation) is defined as the presence of itch over a wide area, and not localized to a specific part of the body. This entity includes idiopathic pruritus, pruritus in the elderly, symptomatic pruritus, pregnancy-associated pruritus, drug-induced pruritus, and psychogenic pruritus. Localized pruritus (without skin inflammation) represents fixed itch localized to a specific part of the body, and includes anogenital pruritus, scalp pruritus, notalgia paresthetica, and brachioradial pruritus. These guidelines outline the current concepts and specify the diagnostic methods/treatments for cutaneous pruritus.

1 BACKGROUND AND ORIENTATION OF THE GUIDELINES

1.1 Background

Cutaneous pruritus designated in these guidelines is a disease characterized by itch without observable rash. Generalized pruritus, which causes itching across the body, is often associated with underlying diseases such as renal failure, liver damage, and hematological disorders. These patients experience marked psychological distress due to long-term severe itch. In addition, it negatively affects daily life, such as sleeping and working, and significantly deteriorates the quality of life.

The mechanism of itch is not fully understood. As only a small percentage of patients with generalized pruritus respond to antihistamines (H1 receptor antagonists), physicians have difficulties controlling itch in these patients. In 2012, we created guidelines for generalized pruritus. However, we revised the guidelines in order to make some of the definitions, diagnostic terms, and classifications more applicable to daily clinical practice.

1.2 Guideline Position

The committee of the Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Intractable Chronic Prurigo and Pruritus is composed of members approved by the Board of Directors of the Japanese Dermatological Association.

The guidelines created by this committee specify the current diagnostic methods and treatment of pruritus in Japan.

2 DEFINITION AND CLASSIFICATION

2.1 Definition and Classification of Cutaneous Pruritus

- 1) Concept:

Cutaneous pruritus: a disease characterized by itch on almost normal skin or skin without apparent lesions (abrasions and/or pigmentation due to scratching may occur).

- 2) Classification:

- a) Generalized pruritus (without skin inflammation):

Presence of itch on a wide area, not localized to a specific part of the body.

- Idiopathic pruritus

- Pruritus in the elderly

- Symptomatic pruritus

- Pregnancy-associated pruritus

- Drug-induced pruritus

- Psychogenic pruritus

-

- b) Localized pruritus (without skin inflammation):

Presence of itch fixed and localized to a specific part of the body

- Anogenital pruritus

- Scalp pruritus

- Special types: notalgia paresthetica and brachioradial pruritus

3 EPIDEMIOLOGY

In a cross-sectional survey of adults conducted in Oslo, Norway, itch was the most common symptom in patients with skin diseases (8.4%).1 In a pilot study involving 200 people in Germany, the point prevalence of pruritus was 13.9%, whereas the lifetime prevalence was 22.6%.2 In studies on the diagnosis rates of pruritus among patients who visited dermatologists in Nigeria, Turkey, and Japan, the rates were 4.2%, 11.5%, and 6.8%, respectively.3-5 Regarding sex, more females were diagnosed with the condition than males.1, 2, 6 In a questionnaire survey conducted in 2009 for 65 university hospitals by the research group in Japan, the mean percentage of outpatients with generalized pruritus was 1.89%.

Patients with generalized pruritus may have underlying diseases.7 Cutaneous pruritus was observed in 1.6–4.6% of pregnant women,8, 9 13% of people with HIV,10 21.3% of people with hepatitis C,11 and 10~77% of people with uremic disease.12

4 PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND MECHANISMS OF ITCH

Generalized pruritus is not well-controlled by antihistamines, H1 receptor antagonists. Itch in generalized pruritus is mediated by non-histamine pruritogens, such as tryptase, substance P, cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-1, -4, -13, and -31, and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), eosinophil products such as eosinophilic cationic protein, major basic protein, and O2−, through direct activation of epidermal nerve fibers by an external mechanical, chemical, and/or physical stimuli, or the involvement of opioids and histamine H4 receptor. Some of these pruritogens cause itch in generalized pruritus depending on the individual disease and/or condition.13-16 The causes of itching in generalized pruritus can be roughly divided into three types,18 those caused by dry skin, by drugs,17 and those associated with an underlying disease (mainly diseases of internal organs).17 However, dry skin often accompanies visceral organ diseases. Usually, itching simply caused by dry skin is responsive to the external use of moisturizing agents.19, 20 However, if this treatment is ineffective, the possibility that generalized pruritus is caused by visceral organ diseases (Table 1) or drugs taken by the patient (Table 2) should be considered.

|

Renal diseases: chronic renal failure, hemodialysis Hepatobiliary diseases: primary biliary cholangitis, obstructive biliary diseases, liver cirrhosis, chronic hepatitis Endocrine and metabolic diseases: thyroid dysfunction, diabetes mellitus, pregnancy, postmenopause, gout, parathyroid dysfunction Blood diseases: polycythemia vera, iron-deficient anemia, malignant lymphoma, hemochromatosis Malignant tumors: malignant lymphoma, chronic leukemia, malignant visceral tumor Nerve diseases: multiple sclerosis, cerebrovascular diseases, brain tumor, locomotor ataxia, progressive paralysis Mental disorder and cardiogenic diseases: delusional parasitosis, neurosis, cardiogenic diseases Others: AIDS, parasitosis |

Note

- Quoted from reference 17.

|

Opioid: morphine, heroin, codeine, cocaine Central nervous system drug: benzodiazepines, meprobamate, carbamazepine, imipramine, barbital Antimalarial drug: chloroquine Anti-inflammatory analgesics: fenoprofen, aspirin, other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, gold preparations Chemotherapy: bleomycin Cardiovascular drugs: captopril, enalapril, clonidine, amiodarone, dopamine, quinidine, digitalis preparations Diuretics: furosemide, hydrochlorothiazide Antibiotics: β-lactam antibiotics, rifampicin, polymyxin B Hormonal agents: progesterone, estrogen, oral contraceptives, dexamethasone Others: hydroxyethyl starch, etretinate |

Note

- Quoted from reference 17.

Dry skin, the most common cause of generalized pruritus, may be induced by environmental factors, such as low humidity, in addition to diminished metabolic function, or it may be associated with underlying diseases. Dry skin is defined as a condition where the skin has a low water content in the stratum corneum, and is often observed in skin diseases like xeroderma, pruritus in the elderly, atopic dermatitis, patients with cholestatic liver diseases, renal failure, diabetes mellitus, HIV infection, and in those undergoing hemodialysis.17 Water retention in the stratum corneum is maintained by sebum membranes, natural moisturizing factors consisting of filaggrin degradation products, and stratum corneum intercellular lipids (mainly ceramide). In recent years, filaggrin gene abnormalities were reported to be involved in dry skin formation.21 A decrease in any of these moisturizing factors promotes dry skin when it is exposed to environmental factors such as reduced metabolic function, low humidity, and excessive washing. Dry skin observed in atopic dermatitis is caused by a decrease in the skin barrier function, an increase in transepidermal water loss (TEWL), and a decrease in the water-holding function of the stratum corneum. However, dry skin in older people (senile xerosis) is caused by the reduction of natural moisturizing factor, epidermal lipids, such as ceramide, and turnover of epidermal cells. However, skin barrier function as assessed by TEWL is not disrupted.22 The cause of itching in dry skin is the infiltration and sprouting of nerve fibers (C fibers) into the epidermis (intra-epidermal nerve growth).23 This causes a decrease in the pruritic threshold and itching is easily induced by mild stimulation.24 Nerve growth factors, such as amphiregulin, gelatinase, and artemin, and nerve repulsion factors, such as semaphorin 3A and anosmin, are involved in the intra-epidermal elongation of C fibers.23-25 Increased expression of nerve growth factors (NGF) and reduced expression of nerve repulsion factors in epidermal keratinocytes are observed in dry skin conditions such as generalized pruritus. Topical moisturizers and ultraviolet (UV) therapy suppress nerve elongation into the epidermis and improves itching.19, 26-28 Drug-induced pruritus occurs less often, but older people often take multiple types of drugs; therefore, if the cause of itch cannot be identified, it is necessary to consider the contribution of drugs. Itch mediated by opioids is observed in chronic renal disease, especially in dialysis patients and liver diseases.29, 30 Itch in these diseases results from an imbalance in the μ- and κ-opioid systems. Activation of μ-opioid receptors stimulates itch perception, whereas κ-opioid-receptor stimulation suppresses itch. In these patients, the expression of itch-inducing μ-opioids are dominant to itch-suppressing κ-opioids.31 Opioids are also expressed in epidermal keratinocytes.32 In atopic dermatitis, the μ-opioid system is dominant to the κ-opioid system; thus, opioids are considered to be involved in the development of itch in peripheral tissues. As topical naloxone ointment as a μ-antagonist can suppress itch in atopic dermatitis,33 opioids may be involved in the development of itch in the periphery. Many itch-inducing factors (pruritogens) are considered to mediate itch in generalized pruritus, which responds poorly to antihistamines.

5 CLINICAL SYMPTOMS

5.1 Symptoms of generalized pruritus

Generalized pruritus is characterized by itch across the body without apparent skin lesions that may cause itching. The itch is persistent or paroxysmal, causing difficulty in sleeping at night. There are variations of itch symptoms. In itch caused by renal failure, dialysis, or cholestasis, this may be experienced as an “itch coming from inside the body” or “sudden itch attack”.

6 LABORATORY TESTS

The most common cause of generalized pruritus is senile xerosis (dry skin).34 Assessment of dry skin usually depends on visual inspection/physical examination, but in order to determine whether pruritus is caused solely by dry skin, exclusion of underlying diseases that may have caused generalized pruritus is necessary. Underlying diseases associated with generalized pruritus include hepatobiliary, renal, blood (hematopoietic tumors such as leukemia and lymphoma), and endocrine or metabolic (such as diabetes mellitus and thyroid dysfunction) diseases, as well as malignant visceral tumors. In addition, drugs and food may induce pruritus. Therefore, the patients should also be asked about the types of oral medication that they are taking, as well as if they habitually take supplements or eat healthy food.

After a detailed interview on the patient’s medical and lifestyle history, tests for each underlying disease should be conducted with physical examinations in order to screen for diseases that may have caused pruritus. Blood tests include blood cell count, leukocyte fraction, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, hepatobiliary enzymes, thyroid hormone, and blood glucose level.

If the cause is not determined and itch persists for a long period, it is necessary to consider the possibility of malignant visceral tumor. The patient must undergo a fecal occult blood test, tumor marker measurements, and imaging evaluations such as chest X-ray and contrast computed tomography.

If the cause cannot be identified even after the aforementioned extensive examinations, the possibility of pruritus due to a mental disorder needs to be considered. A considerable number of pruritus cases may be caused by mental disorders, although it is not possible to confirm a causal relationship between psychological conditions and itch.

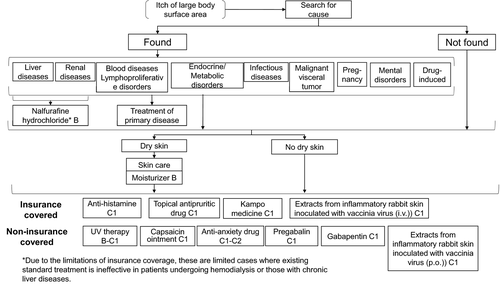

7 PRURITUS TREATMENT ALGORITHM

| 1. Washing, daily baths, shower |

|

Remove sweat and dirt. However, avoid intensely rubbing skin. When using soap and shampoo, avoid using products that have strong detergency. Rinse soap and shampoo thoroughly to completely remove residue. Avoid hot water that causes itching. Avoid bathing agents and bath powders that cause a burning sensation. Avoid using nylon or hard towels. |

| 2. Others |

|

Keep your room clean, and maintain appropriate temperature and humidity. Wash new underwear with water before use. Thoroughly rinse off the detergent. Cut your nails short and try not to scratch your skin. It may be useful to use gloves or bandages for protection. |

Note

- Quoted and reorganized from the 2005 Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis by Yoichi et al., Health and Labor Sciences Research.

8 CLINICAL QUESTIONS (CQ)

CQ1: Are moisturizers effective for pruritus?

Level of Recommendation: B (Appendix 1).

Statement of Recommendation: The use of moisturizers may reduce itch for generalized pruritus accompanied by dry skin. However, their effects on pruritus without dry skin is unclear. If topical moisturizers are ineffective, switching to other treatments is recommended.

Comments: Generalized pruritus includes pruritus in the elderly, and pruritus associated with diabetes mellitus and renal failure. These are often accompanied by dry skin. The use of moisturizers restores the stratum corneum barrier in dry skin and alleviates skin symptoms such as itch.35 A decrease in the pruritic threshold induced by the activation of keratinocytes and elongation of nerve fibers into the epidermis has been reported as one of the mechanisms for itch associated with dry skin.36 There are several clinical reports regarding the effects of moisturizers on itch in dry skin. The use of heparinoid for 2 weeks was reported to alleviate itch in a limited number of cases (Evidence Level IV).37 Herbal moisturizers and moisturizers containing urea, lactic acid, and propylene glycol can reduce itch in all groups (Evidence Level II).38 For pruritus associated with renal failure, the visual analog scale (VAS) score for itch of the group that used a topical moisturizer (two times/day for 2 weeks) decreased compared with that of the group that did not use a topical moisturizer (Evidence Level III).39 Based on the above, we recommend the clinical use of moisturizers for pruritus caused by dry skin. On the other hand, there are no reports regarding the clinical effects of topical moisturizers on pruritus without dry skin. Therefore, we recommend switching to another treatment method if moisturizers are ineffective for pruritus without dry skin.

CQ2: Are antihistamines effective for pruritus?

Level of Recommendation: C1.

Statement of Recommendation: There are no studies with a high Evidence Level. Its use may be considered, although the clinical evidence is not sufficient.

Comments: There is a report demonstrating that cetirizine, doxepin, and hydroxyzine suppressed pruritus scores by 65%, 75%, and 80%, respectively, in a 4-week randomized, double-blind study of sulfur mustard-induced pruritus (Evidence Level II).40 However, there have been no randomized, double-blind studies on antihistamines for generalized pruritus. There is a randomized controlled study evaluating the antipruritic effects of the antidepressant doxepin, which has antihistaminergic action in dialysis patients.41 An open study with 398 patients examined the effects of olopatadine on itch sensation in several pruritic diseases. The effects were observed in 74.6% of the eczema group, 50.8% of the prurigo group, and 52.8% of the generalized pruritus group.42 Although there have been several clinical trials involving antihistamines for pruritic skin diseases, including generalized pruritus, these studies yielded low Evidence Levels.43 However, in a review of pruritic skin diseases, antihistamines were recommended as a first-choice drug;44 thus, they are recommended to be one of the first-line drugs even for generalized pruritus. The diagnosis and treatment guidelines for atopic dermatitis set non-sedating or less sedating second-generation antihistamines as a first-choice drug (Table 4). The guidelines also advise additional administration of other antihistamines while observing additional side-effects and antipruritic effects.45 A recent review regarding cutaneous pruritus stated that the use of antihistamines can be considered as an initial treatment, although double-blind studies on antihistamines for cutaneous pruritus have not been conducted.46 There is little evidence, but the guideline committee set antihistamines as a first-line drug as an expert opinion based on antihistamines being commonly used as the first-line drugs in most cases. Clinically, the selection of drugs requires thorough consideration because this disease is not uncommon in the elderly. Physicians should pay attention to glaucoma, prostatic hyperplasia, and liver damage or decreased renal function, which are observed in elderly patients at a high incidence. As for the detailed side-effects regarding antihistamines, we advise referencing the 2018 “Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis”.47

|

(1) Non-sedative Fexofenadine hydrochloride (Allegra®) Epinastine hydrochloride (Alesion®) Levocetirizine dihydrochloride (Xyzal®) Ebastine (Ebastel®) Loratadine (Claritin®) Cetirizine hydrochloride (10 mg) (Zyrtec®) Olopatadine hydrochloride (Allelock®) Bepotastine besilate (Talion®) Desloratadine (Desalex®) Bilastine (Bilanoa®) Rupatadine (Rupafin®) (2) Mild sedative Azelastine hydrochloride (Azeptin®) Mequitazine (Nipolazin, Zesulan®) Cetirizine hydrochloride (20 mg) (Zyrtec®) (3) Sedative d-chlorpheniramine maleate (Polaramine®, Neomallermin TR®) Oxatomide (Celtect®) Diphenhydramine hydrochloride (Vena, Restamin®) Ketotifen fumarate (Zaditen®) |

Note

- Referenced and revised from “Atopic dermatitis clinical guidelines”, Jpn J Dermatol, 2016; 126:121–55, eds. Japanese Dermatological Association.

CQ3: Are topical steroids effective for pruritus?

Level of Recommendation: C2, but B in the case of cutaneous pruritus accompanied by eczematous lesions.

Statement of Recommendation: The effects of topical steroids on cutaneous pruritus are unclear and there are no reports with high levels of evidence. Regarding anogenital pruritus, there have been reports on topical steroids equivalent to Evidence Level II. However, eczematous lesions were included in the evaluation, which are not referred to as anogenital pruritus. Topical steroids are recommended only if there are secondary eczematous lesions.

Comments: The effects of topical steroids on pruritus without skin lesions are unclear and there are no reports with high levels of evidence. Regarding anogenital pruritus, there is a report with a high level of evidence (Evidence Level II) on topical steroids,48 but eczematous lesions were included in the evaluation, which are different from anogenital pruritus defined in these guidelines.

Currently, topical steroids covered by insurance for cutaneous pruritus only include betamethasone valerate, fluocinolone acetonide, and dexamethasone. The American Academy of Dermatology’s guidelines for the usage of topical glucocorticosteroids states that “topical steroids may also be effective for skin symptoms such as burning and itching sensations”.49 However, the guidelines did not provide clear evidence (Evidence Level V). Although betamethasone valerate can be used as a topical steroid for pruritus, all of the abovementioned effects may be based on diseases from the prurigo group (such as urticaria perstans and strophulus), but it is unclear whether it is effective for itch caused by urticaria or for generalized/localized pruritus. Indeed, the use of topical steroids is not mentioned in the global guidelines for urticaria (Evidence Level V). Histamine, a representative pruritogen, is released from mast cells, which are widely distributed in the skin, lungs, and nasal mucosa, and mediates urticaria, asthma, and rhinitis. Steroids suppress the antigen-stimulated release of histamines from mast cells in mice and rats but do not provide immediate relief of symptoms, as there is a time lag in the effect onset.50 There are also several reports stating that there is a difference between the histamine release caused by antigen stimulation and calcium ionophores, and that histamine release by steroids is not suppressed in human mast cells.51 On the other hand, the external use of 0.05% clobetasol propionate ointment significantly reduced itch induced by i.d. histamine injection in 16 healthy subjects.52 However, it is plausible that pruritogens other than histamine are involved in the itch sensation of generalized/localized pruritus. Furthermore, considering side-effects from long-term external use, we cannot recommend topical steroids for itch in generalized/localized pruritus.

Although different forms of topical steroids are effective for itch caused by dry skin in atopic dermatitis and asteatotic dermatitis, itch is mediated by cytokines/chemokines regulating eosinophils and lymphocytes; these are inhibited by corticosteroids.53 It is thought that itch in dialysis-related generalized pruritus and asteatotic dermatitis is caused by the maldistribution of peripheral nerves, and that steroids suppress itching by controlling this process.54

Indeed, the anti-inflammatory activity of steroids includes anti-inflammatory, anti-allergenic, and immunosuppressive actions. The anti-inflammatory action suppresses the damage of cell membranes of vascular endothelial cells and lymphocytes in the inflamed area of the skin such as in contact dermatitis. This affects the equilibrium of the membrane within a few seconds.55 Steroids also suppress the function of phospholipase A2, an important enzyme that induces inflammation-associated molecules, such as leukotrienes and prostaglandins, from phospholipids in the cell membrane. These actions may be effective for itching by repairing damage of peripheral nerve C fibers.

Lastly, we discuss new pathomechanisms of itch that are becoming clearer or can be used in the future as therapeutic targets, as well as new therapeutic agents. It is necessary to understand how these pathologies or agents are controlled by topical steroids. Based on new findings, IL-31 is involved not only in the transmission of itch, but also in the growth and development of sensory nerves in the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) independently from NGF. As this reaction is signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)3-dependent and transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1 (TRPV1)-independent, it can be suppressed by STAT3 inhibitors. Thus, IL-31 antibodies and/or STAT3 inhibitors should be effective for suppressing itch induced by inflammation.56 Steroids are able to control STAT3. It was recently reported that IL-4 receptors are present in the DRG in both mice and humans, and react to chronic itch stimuli.57 These novel findings will aid in the development of Janus kinase inhibitors and STAT3- and STAT6-targeted drugs. In addition to T-helper 2 and mast cells, dupilumab (anti-IL-4Rα antibody) targets IL-4R of the DRG and may exert antipruritic effects. The biological significance of IL-4 compared with IL-31 and how IL-4 reaches and activates the DRG in humans need to be further studied. As in TSLP, IL-4 production is controlled by nuclear factor-κB. Steroids may exert synergistic effects for itch treatment through this process. Generalized pruritus associated with malignant visceral tumors exhibits itch with or without observable rash such as urticaria-like erythema, prurigo reactions, and erythroderma. For patients with intractable or even normal itch, it is necessary to examine latent internal malignancy. We also reported that treatment of malignant visceral tumors improves intractable itch.58 Recently, McNeil et al.59 reported a new mechanism through which low molecular weight substances cause histamine release via Mrgprb2 (MAS-related G-protein coupled recepptor member B2), leading to the provocation of itch. The development of several novel anticancer drugs may be one of the reasons why the number of cancer patients with itch is increasing. Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), which is produced by autotaxin, was reported to be involved in the itch associated with cholestasis. Hashimoto et al.60 reported the therapeutic effects of H1 receptor antagonists against LPA-induced itch. Although there are previous reports regarding itch associated with liver disease, only a few studies stated the possible efficacy of antihistamines. We believe that this will be the subject of future studies. Until now, itch caused by substance P was thought to involve histamine through the induction of the degranulation of mast cells. However, it was recently reported that substance P induces histamine-independent itch, acts as a ligand for human MRGPRX2 (MAS-related G-protein coupled receptor member X2), and that its antagonist suppresses histamine-independent itch. These reports provide new targets for substance P inhibitors.61 Yosipovitch et al. reported the mechanism of itch in a mouse model of psoriasis and the effects of an anti-IL-17A antibody.62, 63 On the other hand, substance P has been implicated in itch in psoriasis patients. Thus, the relationship between substance P and IL-17A signals is of interest; however, to what extent the findings in mice can be applied to human diseases remains unclear.64 It is necessary to examine the biological actions of steroids on the production of pruritogens such as IL-17A, tachykinin, and autotaxin. Katayama et al.65, 66 previously reported cases in which the external application of vitamin D3 analogs was effective against topical steroid-resistant chronic prurigo. Changing the therapy from topical steroids to excimer lamp irradiation also resulted in clinical improvement in cases of intractable itch.67 Therefore, we may also need to consider the possibility that corticosteroids aggravate rather than ameliorate itch sensation.68

CQ4: Is topical crotamiton (Eurax®) effective for pruritus?

Level of Recommendation: C1.

Statement of Recommendation: There are no studies on the antipruritic effects of topical crotamiton with a high level of evidence. Its use can be considered, but there is insufficient evidence. It is also not covered by insurance.

Comments: At present, the most commonly used antipruritic topical medicine in Japan (Table 5) is crotamiton cream (Eurax). Crotamiton (crotonyl-N-ethyl-o-toluidine) was a compound first reported by Domenjoz in 194669 and originally presented as a therapeutic agent for scabies. In 1949, Couperus70 reported its antipruritic effects. Subsequently, a combination drug of crotamiton and hydrocortisone was made. This combination drug called Eurax H® became a popular topical medicine for pruritic skin diseases. Currently, Eurax H can be easily obtained as an over-the-counter drug.

| 1. Topical antipruritics |

|

Crotamiton formulations (Eurax® cream) Diphenhydramine formulations (Restamin® Kowa ointment, Vena Pasta® ointment) |

| 2. Moisturizer |

|

Heparinoid formulations (Hirudoid® cream, Hirudoid® soft ointment, Hirudoid® lotion) Urea formulations (Urepearl® ointment, Urepearl® lotion, Keratinamine ointment, Pastaron® ointment, Pastaron® 20 ointment, Pastaron® soft cream, Pastaron® 20 soft cream, Pastaron® 10 lotion) Vaseline Hydrophilic ointment |

No high-level analyses of the antipruritic effects of crotamiton on cutaneous pruritus have been conducted, and only a few case series are available (Evidence Level V). In addition, in a placebo-controlled double-blind study that analyzed the antipruritic effects of crotamiton alone in 31 cases of atopic dermatitis and insect bites,71 there was no significant difference compared with the vehicle (Evidence Level II).

CQ5: Is UV light therapy effective for pruritus?

Level of Recommendation: B or C1.

B for broadband UV-B, and C1 for narrowband UV-B, UV-A, and excimer light.

Statement of Recommendation: There have been no studies with a high Evidence Level that analyzed the usefulness of UV for generalized/localized pruritus. However, recent case reports revealed the usefulness of broadband UV-B for generalized pruritus associated with renal dysfunction, suggesting it to be a potential treatment modality. On the other hand, studies on the usefulness of narrowband UV-B and UV-A have low Evidence Levels. UV light therapy is not covered by insurance.

Comments: In general, it is highly difficult to evaluate the usefulness of therapies for pruritus as many underlying diseases are involved in its etiology. Furthermore, clinical effects of therapies may be influenced by the cause because the degrees of causal involvement vary. In addition, as the symptoms of this disease are mainly subjective, the judgment of the therapeutic effects relies on the subjectivity of the patient. As this disease is relatively common among elderly patients, it is also often difficult to judge how strictly they followed the instructions for the external application of the drugs. In general, the treatments performed and observed by physicians at hospitals regularly tend to be considered effective. Thus, the usefulness of UV therapy performed at hospitals may be overestimated and need to be carefully evaluated.

Randomized controlled trials examining the usefulness of UV therapy for pruritis caused by renal dysfunction were previously performed (Evidence Level II and III).72, 73 In these studies, broadband UV-B (290–320 nm) administrated 6–8 times, twice a week, exhibited clinical effects. Moreover, the effects covered the entire body even if only half of the body was irradiated. These therapeutic effects were considered to be achieved through a systemic rather than localized action.

Ultraviolet B irradiation may cause side-effects such as carcinogenesis. The side-effects of narrowband UV-B are being evaluated. According to a case series on 10 patients with generalized pruritus associated with polycythemia vera (Evidence Level V),74 narrowband UV-B irradiation for 2–10 weeks (total dose, 3271–7366 mJ/cm2) achieved full remission. The entire body was initially irradiated three times a week, starting with two-thirds of the minimum erythema dose. The only side-effect was redness at the irradiation site; however, 8 months after treatment discontinuation, there was recurrence, for which continuous irradiation approximately once a week was useful.

On the other hand, a case series reported that broadband, but not narrowband, UV-B was useful for generalized pruritus associated with renal dysfunction (Evidence Level V).75 This study consisted of three stages. Broadband UV-B, five times a week, was administrated first, followed by narrowband UV-B, before administrating broadband UV-B again. The first broadband UV-B led to remission for 7 months with eight sessions of irradiation (starting at 30 mJ/cm2 and increased to 100 mJ/cm2). When treatment was switched to narrowband UV-B (starting at 200 mJ/cm2 and increased to 500 mJ/cm2), remission was not observed. When broadband UV-B (40 mJ/cm2) was administrated again, remission was achieved after 10 sessions of irradiation, which continued for 8 months. It should be noted that broadband UV-B is effective for generalized pruritus at a lower total dose than for psoriasis. As these data are from Taiwan, whose people have the same skin color as Japanese, broadband UV-B can be the first choice of treatment for patients with generalized pruritus. However, a recent report on pruritus associated with renal dysfunction stated that among the cases in which only 20% remission was achieved by broadband UV-B, one case exhibited alleviation of itch through Goeckerman therapy, which was conducted 23 times. The therapy involved 2% coal tar application for 4–5 h to the affected area and applying triamcinolone ointment five times a week after broadband UV-B (Evidence Level V).76

The effects of excimer light on pruritus have yet to be examined. In animal models with dry skin using Nc/Nga mice, itch was prevented by inhibiting nerve fiber elongation into the epidermis.27 Excimer light therapy may be considered as an option for the treatment of generalized/localized pruritus.

CQ6: Are topical and oral immunosuppressants effective on pruritus?

Level of Recommendation: C2 for both topical and oral medicine.

Statement of Recommendation: The use of immunosuppressants is not recommended because of the lack of clinical evidence. It is also not covered by insurance.

Comments: Duque et al.77 examined the antipruritic effects of 0.1% tacrolimus ointment in a randomized double-blind study of 22 patients with pruritus undergoing dialysis (Evidence Level II). No difference in the degree of itch between tacrolimus ointment and the control group was observed. In contrast, there is a case report stating that 0.03% tacrolimus ointment suppressed itch in patients undergoing dialysis with severe pruritus.78 However, it has a low Evidence Level due to the absence of a control. Therefore, we do not recommend the use of immunosuppressants due to insufficient evidence. Moreover, we do not recommend oral immunosuppressants as they have not been thoroughly examined. However, a recent review stated that immunosuppressants may be considered while paying careful attention to side-effects when pruritus is severe.46

CQ7: Is capsaicin ointment effective for pruritus?

Level of Recommendation: C1.

Statement of Recommendation: Capsaicin ointment is basically not recommended, but its use may be considered if itch is intractable and other drugs are ineffective. Capsaicin ointment is not covered by insurance.

Comments: Capsaicin, a component of chili peppers, exerts pharmacological effects by acting on TRPV1. TRPV1 detects temperatures over 43℃, but is also activated by acid stimulation and capsaicin. Thus, reduced pH due to inflammation or capsaicin application induces a tingling burning sensation through TRPV1.

Transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1 is expressed on C fibers of peripheral nerves containing substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) that transmit itch. Consistent with this, it was reported that histamine-induced itch was reduced in TRPV1 knockout mice.79 This revealed the role of TRPV1 in neurogenic inflammation and itch transmission. However, when TRPV1 is repeatedly stimulated, intracellular Ca2+ and the calmodulin complex bind to TRPV1 and inactivate channels, resulting in extracellular Ca2+-dependent desensitization of TRPV1. Therefore, continuous stimulation of TRPV1 by capsaicin ointment induces the desensitization of TRPV1-positive peripheral nerves. Attempts to treat neuropathic pain are still ongoing. Zostrix and Capzasin-P are currently sold as over-the-counter drugs in the USA.

Capsaicin is expected to be effective for pruritus through similar mechanisms. There are only a few previous studies on the efficacy of capsaicin ointment (0.025–0.075%) for generalized pruritus and prurigo nodularis in dialysis patients (Evidence Level II to III).80-83 There were also studies regarding patients undergoing dialysis due to renal failure and those with psoriasis-induced itch (Evidence Level II).84, 85 It has been reported that 0.025% capsaicin cream is effective for notalgia paresthetica, which is a special type of localized pruritus (Evidence Level II).86 In recent years, the therapeutic effects of an 8% capsaicin patch on notalgia paresthetica and brachioradial pruritus have been reported (Evidence Level V).87 Although there are no reports demonstrating its effects on pruritus associated with other diseases and it is not covered by insurance, capsaicin ointment may be an option in cases of treatment-resistant pruritus.

CQ8: Are anti-anxiety drugs and antidepressants effective for pruritus?

Level of Recommendation: When skilled in their use, C1; when not skilled in their use, C2.

Statement of Recommendation: The administration of anti-anxiety drugs and antidepressants may be considered in cases resistant to other treatments. They should not be administrated if the physician is not familiar with their administration.

Comments: Serotonin is known to be involved in chronic itch. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), an antidepressant, has been used as a treatment for generalized pruritus and its effects have been confirmed. There are case series stating that paroxetine alleviated itch in patients with terminal cancer, polycythemia vera, and psychological anxiety (Evidence Level V).88-90 Paroxetine significantly alleviated itch in a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study examining the effects of oral paroxetine (20 mg/day) in 26 cases of primary, drug-induced, paraneoplastic, and cholestatic pruritis (Evidence Level II).91 According to a Cochrane statistical review examining the effects of drug therapy on pruritus in patients receiving palliative care, a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study (n = 48) on paroxetine, which is an SSRI, found that paroxetine was a useful treatment option as it significantly alleviated itch compared with placebo.92 Although the mechanism through which SSRI suppress itch is not clear, it is hypothesized that this action is due to the decreased expression of 5-HT3 receptors in the postsynaptic membrane. There is a case series on pruritus in which the SSRI (e.g., mirtazapine [noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant] as another antidepressant) acted on serotonin receptors in the peripheral nerves.93 Significant improvement was observed in the itch symptoms of paraneoplastic pruritus and nighttime pruritus without depression (Evidence Level V).94

In Japan, there are case reports demonstrating that paroxetine reduced itch associated with liver cancer and in depressive patients with atopic dermatitis (Evidence Level V and III, respectively).95, 96 In atopic dermatitis, tandospirone (an anti-anxiety drug) significantly alleviated itch in patients with moderate skin symptoms and high levels of trait anxiety and state anxiety.96 In a double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study examining the effects of nitrazepam, a benzodiazepine anti-anxiety drug, on nighttime scratching behavior in atopic dermatitis, nitrazepam significantly suppressed itch and nocturnal scratching behavior (Evidence Level III).97 Overseas, the effects of antidepressants, such as paroxetine and mirtazapine, on pruritus have been confirmed. Thus, anti-anxiety drugs and antidepressants are considered useful for pruritus patients with a poor response to treatment. However, they are not covered by insurance. Attention should be paid to their side-effects, which include gastrointestinal symptoms like nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, and constipation, in addition to cardiovascular symptoms, suppressive action on the central nervous system, and drug eruptions (Evidence Level II).98, 99 If the physician is not familiar with the use of psychotropic drugs, it is necessary to consult a specialist (psychiatrist) when considering administration.

CQ9: Is oral nalfurafine hydrochloride (Remitch®) effective for pruritus?

Level of Recommendation: B for hemodialysis patients and chronic liver disease patients, and C2 for pruritus associated with other causes.

Statement of Recommendation: There are no epidemiological studies examining the effectiveness of nalfurafine hydrochloride for generalized pruritus associated with underlying diseases other than hemodialysis and chronic liver diseases. It is recommended for hemodialysis patients and patients with chronic liver diseases, but not in other cases due to the lack of evidence. It is also not covered by insurance in Japan.

Comments: Itch in the central nervous system is regulated by balancing the opioids (i.e., morphine), which induce itch when μ-receptors are stimulated and suppress itch when κ-receptors are stimulated. Nalfurafine hydrochloride is a new drug that suppresses itch in the central nervous system by stimulating κ-receptors and is expected to be effective for antihistamine-resistant pruritus. Nalfurafine hydrochloride not only suppresses itch caused by morphine, but also that caused by histamine and substance P in mice.100

At present, nalfurafine hydrochloride is only covered by insurance for “alleviation of itch in hemodialysis patients and patients with chronic liver disease (only when there is a poor response to standard treatments)” in Japan. In a randomized controlled study, nalfurafine alleviated itch in patients with generalized pruritus undergoing hemodialysis and in those with chronic hepatic failure (Evidence Level II).101, 102 There is also a report demonstrating the antipruritic effects of nalfurafine hydrochloride in a murine model of atopic dermatitis.103, 104

There are no epidemiological studies or case reports examining the antipruritic effects against prurigo nodularis. Therefore, the effectiveness of nalfurafine hydrochloride for prurigo nodularis is currently unclear. However, there is a study reporting that naloxone, a μ-receptor antagonist, was effective for prurigo nodularis (Evidence Level V),105 but these findings require further validation. At present, there is no evidence of its effectiveness, and as it is not covered by insurance, we do not recommend it for general use. Future investigations are expected.

CQ10: Is reserpine effective for pruritus?

Level of Recommendation: C2.

Statement of Recommendation: There is insufficient evidence supporting the efficacy and safety of reserpine for pruritus. It is also not covered by insurance in Japan. Although it may possess antipruritic action due to its pharmacological effects, reserpine administration is not recommended at this stage.

Comments: Reserpine is a Rauwolfia alkaloid isolated from Rauwolfia serpentina. Reserpine possesses inhibitory effects on excitatory transmission at the adrenergic synapses by inhibiting the uptake of catecholamines and depleting noradrenaline in synaptic vesicles, suggesting it to be a hypotensive drug. It also releases serotonin and catecholamines in the central nervous system, suppressing and depleting reuptake, and has ataractic action. Therefore, reserpine is effective in hypertension, malignant hypertension, and schizophrenia cases where phenothiazine cannot be used. A depressive state is a serious side-effect of this drug and this effect may continue for several months even after discontinuation. Due to this, it is contraindicated for patients with a history of depression or depressive state. It is also contraindicated for patients with peptic gastric ulcers and ulcerative colitis.106, 107

The descending noradrenaline pathway in the spinal cord is known to suppress itch.108 Administration of reserpine may inhibit noradrenaline reuptake, increase the noradrenaline concentration in the synaptic cleft, and suppress itch. In addition, it has inhibitory effects on T-cell activation109 and depletes serotonin in mast cells;106, 107 these effects may also lead to the alleviation of itch. There are case reports106 and series107, 110 of Evidence Level V demonstrating the effectiveness of reserpine on pruritic skin diseases, including prurigo chronica multiformis, intractable urticaria, and urticarial vasculitis, suggesting that reserpine is effective for generalized pruritus.

CQ11: Is pregabalin effective for pruritus?

Level of Recommendation: C1.

Statement of Recommendation: There is good evidence that pregabalin is effective for generalized pruritus associated with dialysis, and there are case reports and series demonstrating its effectiveness for generalized pruritus induced by other causes. Considering its use can be a good treatment option. However, it is not covered by insurance in Japan.

Comments: Pregabalin and gabapentin have similar chemical structures and biological actions. They act on voltage-gated calcium channels in the central and peripheral nervous systems, and suppress the secretion of excitatory neurotransmitters, such as glutamate, substance P, and CGRP, in the hyper-excited state. Therefore, it is believed that this increases the threshold for itch sensation.111 The indication of pregabalin is “neuropathic pain and pain associated with fibromyalgia”. It is not covered by insurance for cutaneous pruritus.

The efficacy of pregabalin on pruritus of dialysis patients was demonstrated in a randomized controlled study of 179 patients. The VAS score significantly decreased compared with placebo and ondansetron (Evidence Level II).112 In addition, there are two reports of open-label trials in which the itch VAS score decreased in dialysis patients (Evidence Level V).113, 114

In patients with polycythemia vera, there have been three case reports in which pregabalin administration reduced the VAS score by more than 70% (Evidence Level V).115

Regarding neuropathic pruritus, there was a case report in which itch due to Brown–Séquard syndrome after trauma was reduced by half (Evidence Level V).116

Based on these reports, there is good evidence supporting the efficacy of this drug for pruritus associated with dialysis. It also may be effective for pruritus induced by other causes, but caution is required because it is not covered by insurance.

For administration, the initial dose, dose titration method, and maximum daily dose need to be strictly set according to the prescribing information. Symptoms, such as somnolence, sedation, and dizziness, may develop during administration, and it is necessary to be careful not to operate machinery such as driving a car. Furthermore, adverse reactions, such as weight gain and eye disorders, may develop during administration.

In addition, serious adverse reactions may occur when abruptly reducing or discontinuing the administration of these drugs; thus, it is necessary to gradually reduce the dose over at least 1 week.

CQ12: Is gabapentin effective for pruritus?

Level of Recommendation: C1.

Statement of Recommendation: There is good evidence that gabapentin is effective for pruritus caused by certain diseases, and its use may be considered. However, it is not covered by insurance in Japan.

Comments: Gabapentin and pregabalin have similar chemical structures and biological actions. They act on voltage-gated calcium channels in the central and peripheral nervous systems, and suppress the secretion of excitatory neurotransmitters, such as glutamate, substance P, and CGRP, in the hyper-excited state. Therefore, it is believed that this increases the threshold for itch sensation.111 The indication of gabapentin is “combination therapy with anti-epileptic drugs for partial seizures (including secondary generalized seizures) in epileptic patients with a poor response to other antiepileptic drugs”. However, it is not covered by insurance for cutaneous pruritus.

Two randomized controlled studies examined its effects on pruritus in dialysis patients. These studies had 25 and 34 subjects, respectively. Patients had dialysis-related itch that was non-responsive to oral anti-histamine and topical moisturizers (Evidence Level II).117, 118 The administration of gabapentin after each dialysis session significantly improved the VAS score. There is a cohort study in which gabapentin improved itching in nephrogenic pruritus even in non-dialysis patients (Evidence Level IV).119

Regarding neuropathic itch, case reports and case series reported improvement of itch in brachioradial pruritus at high doses (900–1800 mg/day).111 For notalgia paresthetica, in an open-label and non-randomized controlled study with 20 subjects, p.o. administration of gabapentin (300 mg/day) demonstrated higher itch suppression effects than topical capsaicin ointment (Evidence Level III).120

A double-blind, randomized, controlled study of 16 patients with cholestatic pruritus was performed at a high maintenance dose of 100–2400 mg/day. The VAS score decreased significantly compared with placebo (Evidence Level II).121

For administration, the initial dose, dose titration method, and maximum daily dose need to be set according to the prescribing information. Symptoms, such as somnolence, sedation, and dizziness, may develop during administration, and it is necessary for patients to be careful not to operate a vehicle or dangerous machinery. Furthermore, adverse reactions, such as weight gain and optical disorders, may develop during administration.

In addition, serious adverse reactions can occur when abruptly reducing or discontinuing administration of these drugs; thus, it is necessary to gradually reduce the dose over at least 1 week.

CQ13: Are Kampo medicines effective for pruritus?

Level of Recommendation: C1.

Statement of Recommendation: As this disease is treatment-resistant, their use may be considered.

Comments: The following randomized controlled studies investigated generalized pruritis in the elderly (Evidence Level II).

In a randomized controlled study using Orengedokuto (medium to excess pattern) and Goshajinkigan (medium to deficient pattern), both demonstrated the same effects as clemastine fumarate (Tavegyl®).122 In addition, the combined effects of Tokiinshi and bath powders containing licorice extract were examined and both medicines improved the water content of the stratum corneum. However, among patients whose dryness was alleviated, less than half experienced the alleviation of itch.123 In a randomized controlled trial using a crossover method with Hachimijiogan and ketotifen fumarate (Zaditen®), 78% effectiveness was confirmed with no significant difference between treatments.124 Furthermore, in comparative studies with Hachimijiogan and Rokumigan, both demonstrated the same effectiveness.125 In addition, Okuma126 reported that the combination of Tokiinshi and Orengedokuto had the same effect as an antihistamine drug for patients with pruritus. However, detailed information, such as age, distribution of patients, and underlying diseases, was not described.

Reports on the clinical effects of Kampo medicines for generalized pruritus in patients with renal failure and undergoing dialysis are mostly descriptive studies. The effects of Orengedokuto,127-130 Unseiin,128, 131, 132 and Tokiinshi128, 131-133 were reported in the form of a case series (Evidence Level V) (Table 6).

CQ14: Are extracts from inflamed cutaneous tissue of rabbits inoculated with vaccinia virus (Neurotropin®) effective for pruritus?

Level of Recommendation: C1.

Statement of Recommendation: As this disease is treatment-resistant, the use of Neurotropin may be considered.

Comments: Neurotropin inhibited capsaicin-induced substance P release and NGF-induced neurite outgrowth in cultured rat DRG neurons in in vitro experiments.134 It also inhibited epidermal nerve fiber elongation in acetone-induced dry skin mouse models and scratching behavior in AD-like models using NC/Nga mice in in vivo experiments.135, 136

A placebo-controlled study of 112 generalized pruritus patients undergoing dialysis revealed significant alleviation of itch (Evidence Level III).137 In a case report in which Neurotropin was administrated to 26 patients with generalized pruritis in the elderly, 53.8% of subjects were markedly responsive (Evidence Level V).138 In other reports, approximately 40% of patients (n = 45) with generalized pruritus exhibited moderate or higher improvement (Evidence Level V).139 Injectable Neurotropin was used in all of these studies. On the other hand, regarding p.o. administration, a placebo-controlled double-blind comparative study was conducted to objectively evaluate its antipruritic effects, especially in chronic urticaria and eczema/dermatitis. The effects were reported to be significantly superior to placebo (Evidence Level II).140 There is also a clinical study report in which 21 patients with generalized pruritus in the elderly received oral Neurotropin and its antipruritic effects were confirmed (Evidence Level V).141 However, the oral preparation is not covered by insurance for pruritus associated with skin diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Ms Yukiko Suganuma for her secretarial assistance.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

APPENDIX 1: Criteria for determining the level of evidence and recommendation

|

A. Classification of the Level of Evidence I. Systematic reviews/meta-analyses II. One or more randomized controlled studies III. Non-randomized controlled studies IV. Analytical epidemiological studies (based on cohort and case–control studies) V. Descriptive study (based on case reports and series) VI. Opinions of the expert committee and individual expertsa B. Classification of the Level of Recommendationb A: Highly recommended (at least one Level I evidence demonstrating effectivity or Level II evidence of good quality) B: Recommended (at least one Level II evidence of effectivity with poor quality, Level III evidence of good quality, or Level IV evidence of extremely good quality) C1: Can be considered but without sufficient basisa (Level III–IV evidence of poor quality, multiple Level V evidence of good quality, or Level IV evidence recognized by the committee) C2: Cannot be recommended due to the absence of basisa (no valid evidence, or evidence of ineffectiveness) D: Not recommended (evidence of good quality that demonstrates ineffectiveness or harm) |

- a Data from basic experiments and derived theories are at this level.

- b Basis refers to findings from clinical studies and epidemiological studies.

- c Some of the recommendations in the text do not necessarily match the above table. It should be noted that B–C1 and C1–C2 should be judged according to individual cases in clinical settings.