Nutrition and Intestinal Rehabilitation of Children With Short Bowel Syndrome

A Position Paper of the ESPGHAN Committee on Nutrition. Part 2

Abstract

Short bowel syndrome (SBS) is the leading cause of intestinal failure (IF) in children. The preferred treatment for IF is parenteral nutrition which may be required until adulthood. The aim of this position paper is to review the available evidence on managing SBS and to provide practical guidance to clinicians dealing with this condition. All members of the Nutrition Committee of the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) contributed to this position paper. Some renowned experts in the field joined the team to guide with their expertise. A systematic literature search was performed from 2005 to May 2021 using PubMed, MEDLINE, and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. In the absence of evidence, recommendations reflect the expert opinion of the authors. Literature on SBS mainly consists of retrospective single-center experience, thus most of the current papers and recommendations are based on expert opinion. All recommendations were voted on by the expert panel and reached >90% agreement. This second part of the position paper is dedicated to the long-term management of children with SBS-IF. The paper mainly focuses on how to achieve intestinal rehabilitation, treatment of complications, and on possible surgical and medical management to increase intestinal absorption.

What Is Known

-

Short bowel syndrome (SBS) is the leading cause of intestinal failure in childhood.

-

First line treatment is parenteral nutrition (PN).

-

Complications of SBS may be related to PN support or the underlying disease and may occur even after PN weaning.

What Is New

-

The use of citrulline and PN dependency index may help to tailor PN weaning in children naturally, pharmacologically, or surgically improving their intestinal absorption capacity.

-

Minimizing or preventing SBS complications from the onset has a key role in helping physiological intestinal adaptation, optimal growth, and weaning from PN at earliest opportunity.

-

A multidisciplinary follow-up including intestinal rehabilitation teams is crucial to prevent those complications.

AIM OF TREATMENT

Optimal Growth

Nutritional Requirements and Intestinal Absorption

The assessment of nutritional requirements in children with short bowel syndrome (SBS) is difficult. Limited available evidences suggest that stable children on home parenteral nutrition (HPN) have similar energy needs to healthy control children matched for sex, age, and weight (1.). As there are no specific data reported on energy needs in children with SBS, and recording resting energy expenditure (REE) from indirect calorimetry is not always feasible, the usual clinical practice is to use REE predictive equations. The most commonly used equation to calculate REE is the Schofield equation 1985 (2.), proposed in the most recent World Health Organization report from 2004 (3.), or the Henry equation (4.), recommended by the latest European Food Safety Authority 2013 (5.) (Supplementary material, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/MPG/D187).

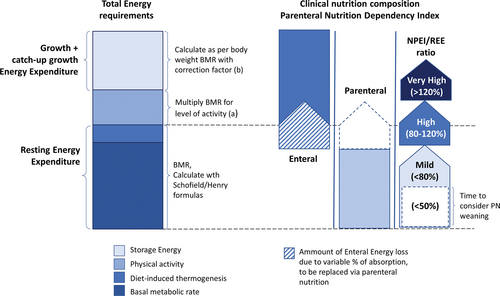

When considering nutritional needs, it is also important to consider that children with intestinal failure (IF) recovering from malnutrition require extra calories for catch-up growth. One pragmatic way is to calculate energy needs based on the 50th percentile of weight for length for age, rather than the actual weight. This can be established by plotting the length of the child on the centile chart, assessing the age corresponding to the 50th centile for this length, and aim for the 50th centile for weight of this age as the basis for calculating energy needs (6.). Alternatively, the requirements calculated from current weight could be multiplied by a correction factor of 1.5–2.1 to meet the additional needs (6.,7.) (Fig. 1).

Nutritional needs and supply for SBS children. aActivity factors as recommended by the latest European Food Safety Authority 2013 (5.). Age in years, weight in kg, and height in meters. bDepending on energy losses and monitoring, a correction factor of 1.5–2 could be applied to achieve a positive energy balance (6.,7.). BMR = basal metabolic rate; NPEI = non-protein energy intake; REE = resting energy expenditure.

However, to really understand energy requirements, the calculated REE should be adjusted by intestinal absorption rate. The intestinal absorption rate can be indirectly calculated from the assessment of energy losses, but this requires specific expertise as well as precisely recording and analyzing all dietary intake and output over several days (8.,9.). Stool balance analysis has been implemented in some research settings to estimate intestinal absorption rate. By precisely calculating the amount of ingested and excreted calories and macronutrients [lipid, carbohydrate (CHO), and nitrogen] over a 3-day period, a measurement of the intestinal absorption rate in terms of total energy, macronutrients, and electrolytes is achieved (8.,9.).

If such analyses are not available, intestinal absorption may be indirectly measured by the PN dependency index (PNDI) (10.). PNDI is the ratio between non-protein energy intake (NPEI), provided by PN for achieving normal or catch-up body weight gain, and REE (6.,8.,11.) estimated with one of the previously cited equations (PNDI = NPEI/REE) (Fig. 1).

Another biochemical marker reflecting intestinal absorption is serum citrulline (12.,13.). Citrulline is a nonessential amino acid produced by small intestinal (SI) enterocytes (14.). As described in a recent meta-analysis, although plasma citrulline levels is helpful, it is not possible to establish effective cut off levels for intestinal sufficiency (13.). Nevertheless, recent studies have demonstrated that longitudinal changes in citrulline level during the adaptation process are correlated with PNDI and with response to hormonal treatment with glucagon like peptide-2 (GLP-2) analogue in SBS children (10.,15.,16.).

R1

-

Energy requirements can be estimated with prediction equations (Henry or Schofield).

-

Parenteral nutrition support must be tailored and adapted according to nutritional status in order to achieve adequate height and weight gain.

-

PNDI can be used as simple tool in clinical practice to estimate changes in PN needs during the adaptation process.

-

Plasma citrulline may be used as a biomarker to longitudinally monitor changes in intestinal absorptive capacity associated with physiological or pharmacological intestinal adaptation.

PP1

-

It is recommended to include requirements for catch-up growth when calculating nutritional needs (energy needs of 50th percentile of weight for length for age or multiplied by correction factor 1.5–2.1).

-

Plasma citrulline could be measured every 6–12 months during the adaptation process or when on GLP-2 treatment.

Nutritional Status

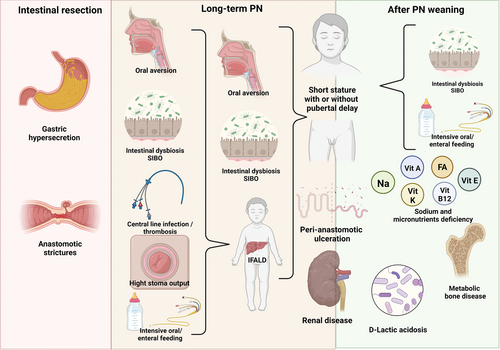

Although the care of children with SBS-IF has improved significantly in recent years, about 50% of the children have short stature for age, and one-third of them have low bone mineral density (17.). Children with chronic mucosal inflammation might be at greatest risk of growth failure (17.). This was confirmed for patients with inflammation linked to primary necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) diagnosis or to catheter related blood-stream infections (CRBSIs) (18.). Other possible causes of failure to thrive in SBS patients are sodium deficiency from high stool output (19.), chronic dysbiosis causing SI bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) (20.), chronic metabolic acidosis (eg, D-lactate) (21.), and intestinal failure associated liver disease (IFALD) (22.) (Fig. 2).

SBS complications according to PN dependency. PN = parenteral nutrition; SBS = short bowel syndrome.

Nutritional status should be monitored in order to adapt nutritional support to the patient’s need. Standard parameters for pediatric malnutrition in clinical practice (23.) include body weight and length and length gain velocity and body mass index (BMI). Above 2 years, height curves should always be weighted according to genetic height target calculated from parents’ height (target height = median of parents’ height + 6.5 cm for boys and − 6.5 cm for girls). These parameters also need to be related to maturational parameters (Tanner stage and bone age), even after PN weaning, since there is a high risk of short stature due to poor prepubertal and pubertal linear growth (24.). Additional anthropometric measures which may help assess correct nutritional status include triceps and subscapular skinfolds and mid upper arm circumference. However, use of standardized equipment and technique should be adopted to minimize variation.

Despite normal anthropometry, body composition may be abnormal in SBS children (25.). In infants with IF requiring PN after intestinal surgery, poor body weight gain was associated with poor fat mass gain, while fat free mass was adequate (26.). However, studies in older children have reported increased adiposity and reduced lean body mass SBS resulting in an apparently correct BMI in children with a higher fat mass (25.,27.,28.). Dual X-ray absorptiometry (DXA), routinely used in SBS children since they are at risk of low mineral bone density (see below), may be an adequate method to assess body composition (25.,29.), however other routine methods avoiding X-ray radiation may be considered.

R2

-

Monitoring nutritional status should include regular anthropometry such as weight and length/height gain velocity and head circumference (<2 years old).

-

Genetic target height and maturational status (bone age, Tanner stage) should be used as a reference for achieving optimal growth.

-

More precise methods of assessing body composition, mid upper arm circumference, skinfolds, and DXA (to assess bone mineral density, as well as fat mass and fat free mass) may be used to monitor and tailor nutrition support.

PP2

-

Anthropometric measurement and nutritional status should be assessed at least twice a year in children with SBS even after PN weaning.

Intestinal Rehabilitation

Home PN administration is the cornerstone of management, promoting quality of life (QoL) for the child and the family with a structured multidisciplinary follow-up after discharge helping to minimize hospital readmissions (30.).

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 15 studies demonstrated that the implementation of an intestinal rehabilitation program has a significant impact on reduction of septicemic episodes and survival of children with IF discharged on HPN (31.). Those results were later reproduced by large Canadian retrospective cohort study (32.). Based on those results, all children on HPN should be followed-up by a specialized multidisciplinary team to ensure that parents are well trained before discharge, and that once home appropriate PN prescriptions, clinical assessment, and laboratory tests are undertaken (33.,34.), with an associated improvement in survival (35.,36.). The overall prognosis of SBS-IF is now expected to be good with survival rate exceeding 90% (37.).

Essential members of an IF rehabilitation program include a pediatric gastroenterologist with training in nutrition, pediatric surgeons, specialized nurses, dietitians, and PN pharmacists (38.). The pediatric gastroenterologist will focus on nutritional assessment and PN prescription, avoidance and treatment of possible complications (see “PREVENTION AND TREATMENT OF SBS-IF COMPLICATIONS”), eventual referral for surgery if needed, and to consider specific treatment to increase intestinal absorption (16.,39.). The specialist nurses are responsible for training parents/carers to administer PN and are important for communication with the family. They offer advice when problems occur with the catheter or the skin around the exit site, the infusion pump, or stoma complications. The dietician should promote an oral diet in order to avoid oral aversion (see below) unless contraindicated (eg, unsafe swallow), but should also be aware of the possibility of hyperphagia (40.,41.) (especially in adolescents) which may increase PN complications (Fig. 2); the diet may need to be adapted, according to digestive tolerance.

Ideally, the central venous catheter (CVC) should be managed by a specialist central venous access team (composed of a critical care pediatric specialist and/or surgeon and/or interventional radiologist with expertise in CVC management). CVC placement should be under radiological control particularly in patients with end stage vascular access (42.).

Living with SBS can negatively impact QoL, for example, the patients require regular follow-up with hospital visits for various clinical treatments that interfere with daily life (43.). Parents’ personal lives are inevitably impacted by the need to deal with venous access, nutritional devices, and life-threatening complications such as septicemic episodes, fluid, and electrolyte imbalance (44.,45.). Patients and caregivers may be affected by depression as an emotional response to the diagnosis, followed by anxiety and fear of the unknown, may lose their jobs, their independence, and social life (46.,47.). The affected child may be aware of limitations, such as fewer opportunities to enjoy the same life as their peers (48.,49.). For all the above reasons the role of the psychologist is crucial (50.).

Depending on the different organization of social care system in each country, social workers may be needed to support setting up HPN and to obtain financial support if not automatically available. A further important support network available in most European countries is a patients and parents association. It may be possible to contact a support group via a European Reference Networks (ERN) such as ERNICA (https://ern-ernica.eu/).

When patients live in isolated settings video contact can be a valuable tool to monitor health status and antibiotic therapy (51.,52.), to detect symptoms of depression (53.), provide emotional support, and to provide instruction as a strategy to reduce complications (54.).

R3

-

Children with SBS discharged on HPN should be monitored by a designated multi-disciplinary intestinal failure rehabilitation (IFR) unit.

-

Minimal requirements for IFR are a pediatric gastroenterologist trained in clinical nutrition, a surgeon, specialized nurse, dietitian, and PN pharmacist.

-

To avoid end-stage vascular access a specialized central venous access team is recommended.

-

Other professionals, such as psychologists, social workers, and speech therapists may also be needed in certain circumstances.

PP3

-

Periodic follow-up should include assessment of patients and family health related QoL to identify symptoms of psychological distress at the earliest opportunity.

-

Telemedicine may be a valuable option to reduce visit frequency and monitor patients in isolated settings.

Parenteral Nutrition Weaning

PN weaning is normally defined as the gradual reduction of PN calories needed by the child while maintaining optimal growth velocity.

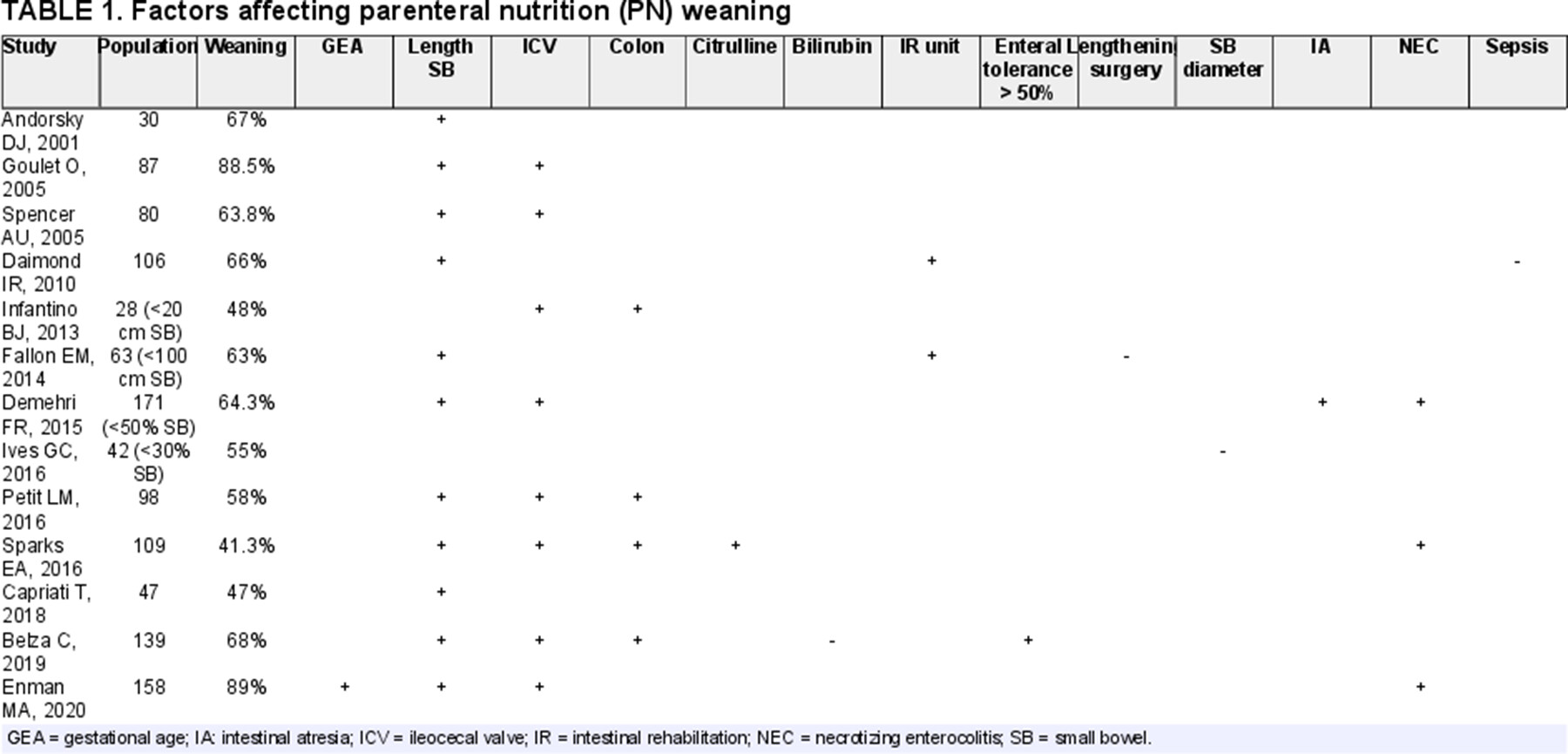

Several retrospective cohort studies have attempted to define the factors predicting PN weaning in children with SBS-IF; results from the latest 20 years are summarized in Table 1 (55.-67.). Total weaning from HPN in SBS is achieved in around 50%–60% of cases discharge home on PN.

Residual SI length as well as presence/absence of the ileocecal valve (ICV) seem to be universally recognized prognostic factors affecting enteral autonomy achievement. Various cut-offs of residual bowel length ranging from 15 to 50 cm or 30%–50% of residual SI have been proposed to predict PN weaning (55.,56.,68.,69.). Two retrospective studies on ultrashort bowel syndrome also reported a rate of enteral autonomy of 25%–50% which was reached during the first 4 years of follow up in children with <20 cm residual SI (59.,65.,70.). In addition the presence of the ICV was questioned as a positive predictive factor by a recent pediatric SBS-IF meta-analysis (71.). Having NEC as primary diagnosis of NEC seems to be a positive predictor for enteral autonomy (71.), whereas having gastroschisis is a negative due to secondary dysmotility (69.). As outlined in Table 1, other factors predicting weaning may be length of residual colon, serum citrulline, enteral tolerance 6 months after resection, and multidisciplinary follow-up. A recent study proposed that PNDI together with longitudinal measurement of citrulline may help predicting PN weaning (10.). Total bilirubin, SI diameter, and the need for a lengthening surgical procedure may have a negative impact due to the link with IFALD development (60.,66.).

Improvement in intestinal absorption rate for children with SBS after weaning from PN support seems to be limited. Thus, SBS patients weaned off PN are at risk of energy or micronutrient deficiency especially during periods of rapid growth such as puberty (72.,73.). Long-time follow-up by an expert IFR team is essential in order to avoid faltering growth or pubertal delay which could particularly affect weaned patients approaching adolescence (Fig. 2).

R4

-

PN weaning should only be considered if the child with SBS is showing appropriate growth.

-

Early PN weaning (<2 years) should be proposed and attempted by IFR caring physicians for infants with more than 20 cm (or >10%) of residual SI and presence of ICV.

-

PN weaning in appropriate settings (IFR unit) may be attempted where SI < 20 cm (or <10%) and presence of ICV (approx. 50% success rate); in case of success a tight follow-up after weaning is mandatory.

PP4

-

When attempting to wean from PN regular follow-up should be intensified to identify signs of nutrient malabsorption.

PREVENTION AND TREATMENT OF SBS-IF COMPLICATIONS (Irrespective of Enteral Autonomy)

In this section we will address potential complications which are correlated with SBS such as oral aversion, gastroesophageal reflux, high output stoma losses, intestinal dysmotility, intestinal mechanical obstruction, SIBO, D-lactic acidosis (D-LA), ulcerative anastomosis, renal disease, metabolic bone disease (MBD), and micronutrient deficiencies.

Other complications that occur in IF, irrespective of the underlying etiology, such as CVC-related complications and IFALD have already been extensively addressed in other ESPGHAN position papers and guidelines (74.,75.). It is important to state that recent advances in managing home-PN with the use of taurolidine locks (76.,77.), using less aggressive enteral tube feeding (ETF) (78.) and the use of intravenous mixed lipid emulsions (79.) have lowered the incidence of IFALD in experienced centers (80.).

Oral Aversion

Children affected by SBS often need PN and enteral feeding tubes for long periods in early life. As a consequence, there may be a delay and dysfunction of the physiological oral feeding processes and approach to food, both in terms of timing and pleasure (81.). Furthermore early ETF as well as early prolonged periods of nil per os have been thought to contribute to delayed acquisition of feeding skills in children with SBS-IF (82.-84.). Late introduction of solid foods, related to long-term hospitalization, could then affect the acquisition of optimal feeding skills (85.,86.). For these reasons, the introduction of small volumes of oral liquids as early as possible after surgery and prompt weaning onto solid food, when allowed according to the patient’s condition (and age in infants), is recommended, and could help avoid oral aversion and other feeding problems.

Children in a pediatric IF study, aged 1–14 years, showed high scores for oral sensitivity, suggesting that some children with IF have oral sensory processing problems (82.). In particular, food aversion, which can be defined as a voluntary refusal of liquids or solids related to previous unpleasant experiences, can be observed in up to a quarter of patients with SBS-IF (87.).

ETF remains an important technique in the management of SBS infants. The use of ETF is driven by the necessity of improving enteral tolerance while decreasing PN dependency. The first attempt of a comparison between 2 IF centers with different feeding practice (ETF vs oral feeding) showed a significantly reduced rate of feeding difficulties in the center preferring oral feeding (82.). Additionally, children with SBS receiving most of their nutrition via ETF do not experience normal hunger-satiety patterns (88.), which may impact on intestinal motility (89.). Oral feeding as opposed to ETF enhances acquisition of feeding skills, maintains self-regulation of hunger and satiety and enjoyment associated with eating, thus helps prevent feeding difficulties (19.,89.).

The family should be involved to promote home healthy eating practices including:

-

allowing the child to make their own food choices and encouraging dietary self-regulation

-

socialization through regular family meals

-

healthy home food

-

association of healthy eating with pleasure (90.).

In conclusion, the balance between the use of oral and/or ETF should take into account the clinical tolerance and acceptance of different feeding techniques as well as patient’s clinical history. However, further studies are needed to better understand the clinical outcomes related to different feeding approaches and nutrition support in SBS children.

Gastroesophageal Reflux

Impaired motor activity of the upper-GI tract is frequent in SBS-IF children. It is multifactorial: for example, altered intestinal anatomy related to the locality and extent of intestinal resection, the effect of the underlying cause of SBS on the neuro-myenteric system (intestinal atresia, sequela of NEC, gastroschisis). Consequently, clinical symptoms should be interpreted very rigorously before any specific investigation procedure.

In the 2018 ESPGHAN-ESPEN guidelines on PN fluid chapter (91.) the benefit of H2 blocker treatment in reducing gastric acid hypersecretion was addressed and all the available evidence described. In 2020 the FDA and European Medicines Agency (EMA) banned the most widely used tested H2 blockers ranitidine (92.), because of possible carcinogenic effect. Even though less powerful (93.,94.), at present proton pump inhibitors (PPI) seem to be the safest choice.

A retrospective study on endoscopic finding in patients with IF showed that 20 of 56 patients enrolled needed gastric acid suppression treatment for esophago-gastro-duodenal findings (95.). However, there is no evidence to support routine use of endoscopy in the absence of symptoms of severe/refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). A comprehensive review on GERD and foregut dysmotility in children with IF, even if not SBS specific, was recently published addressing etiology and possible therapeutic options (96.).

Intestinal Motility Disorders

Children with SBS are at risk of dysmotility which may result from abnormal development of the neuro-myenteric system (97.), for example, intestinal atresia, or as a consequence of ischemic injury to the enteric nervous system and smooth muscle, such as in NEC, gastroschisis (69.), intestinal atresia, or midgut volvulus. Dysmotility may manifest as poor peristalsis, gastroparesis, or rapid intestinal transit (98.). Dysmotility in SBS children is a very common complication affecting >50% of cases with clinical presentation varying from food intolerance with abdominal distension and vomiting to severe constipation (99.,100.).

There are no clinical trials on the use of metoclopramide or domperidone in children with SBS, although a large retrospective cohort observation seemed to reveal that nearly 60% of children increases EN tolerance with these medications (100.). The only prokinetic clinical trials are a double-blinded placebo controlled study on erythromycin in postoperative gastroschisis patients, which failed to demonstrate any effect on feeding tolerance (101.) and an open label pilot clinical trial on cisapride which demonstrated improved enteral tolerance in 7 of the 10 SBS children enrolled (102.). However, the use of cisapride has been restricted or forbidden on some countries because of the risk of QT prolongation leading to potentially life-threatening cardiac arrythmia. Antidiarrheal agents and cholestyramine have never been tested in clinical trials in children with SBS. However, in clinical practice under tight surveillance from an IFR unit, they may be considered to reduce stool output (103.).

Surgical reconstructive techniques may be used to treat motility disorders in SBS children and are discussed in the appropriate section (see below) (99.,100.).

Intestinal Mechanical Obstruction

As highlighted in the first report of the pediatric IF consortium, 25% of surgical interventions occurring with IF are small bowel resections (104.). A recent systematic review highlighted that adhesive obstruction can occur in 1%–12% of children following primary abdominal surgery (105.). When intestinal obstruction was suspected clinically and on abdominal X-ray, the majority of patients needed additional surgery to resolve the problem (105.). In a retrospective review of 98 charts of SBS children, 5 patients were diagnosed with postoperative SI anastomotic strictures on a small bowel radiological follow-through and successfully managed with a fluoroscopy guided balloon dilation (106.). Caution is needed in fragile small bowel due to short anastomosis delay or important perianastomotic inflammation, in order to avoid post-endoscopy complications.

High Stoma Output and Risk of Dehydration

An intestinal stoma plays a pivotal role in IF resection (107.) and can represent a difficult challenge in cases of high volume output.

In children with a high-output stoma intestinal fluid absorption may be impaired, and consequently electrolyte disturbances from sodium depletion and acute or chronic dehydration are frequent complications (20.).

Physiologically the jejunum tries to make the food bolus have the same osmolality as plasma by secreting sodium (Na) or fluid depending on whether the solution is hypo- or hyperosmolar (108.). In normal conditions, sodium and water are reabsorbed by the distal bowel. When the distal colon is not in continuity, there may be loss of sodium and fluids which, if not correctly replenished, can result in dehydration, hyponatremia, and reduced natriuresis reflecting sodium depletion. It is important to emphasize the need for adequate sodium intake and the maintenance of a sodium replete state to optimize growth, even promoting salty food or feeds in SBS-IF (6.).

In order to avoid sodium and/or water depletion, ingested liquids should be iso-osmolar to the plasma, especially in the early stages after stoma surgery, when adaptation mechanisms have not yet developed (12.). Patients with a stoma should be trained to minimize consumption of hypotonic solutions, such as water, tea, coffee, or hypertonic solutions such as soft drinks and most commercial sip feeds (13.). The recommendation is to satisfy most fluid requirement through controlled osmolarity solutions of about 300 mmol/L. It is then suggested to use a saline solution containing glucose, such as oral rehydration solutions used for diarrhea, however increasing the recommended concentration until the desired osmolarity is reached. This increase in concentration will allow a higher sodium concentration to favor sodium replenishment and increase natriuresis. As already mentioned in the first part a valid method to monitor sodium intake is the measurement of sodium on spot urine samples (109.); this should be maintained >20 mmol/L and exceed urinary potassium (NaU/KU > 1) in all SBS children if diuretics are not used. There is no evidence on how frequently natriuresis should be monitored in SBS children either on PN support or after PN weaning.

Dysbiosis and SI Bacterial Overgrowth

Recent studies have pointed out some important differences between the intestinal microbiome in parenterally fed SBS-IF patients versus healthy children such as decrease in richness with a shift from Firmicutes to Proteobacteria and overabundance of Lactobacillus (110.-115.). Gastrointestinal factors (underlying disease, anatomy, feeding tubes, motility), nutritional factors (type and mode of delivery), and pharmacological treatments (antibiotics, antiacid, and drugs affecting motility) are all implicated in microbiome modulation in SBS (116.). Patients receiving cyclic PN seem to have a relatively normal intestinal bacterial species ratio (117.). Microbiota alteration may promote inflammation and development of SIBO (118.) and also be implicated in CRBSI and IFALD development (110.,119.), although it is not known whether the altered microbiome is a primary or secondary problem.

The prevalence of SIBO in children with SBS was estimated at around 70% in 2 retrospective studies (20.,120.), however the 2 papers widely differed in design and the diagnostic tools used to confirm clinical suspicion. To date there are no studies available to validate diagnostic tools for SIBO in children with SBS.

Recent intestinal microbiome studies have demonstrated that the wide use of antibiotics, especially prophylactic use, may unfavorably alter microbiota composition (121.). Studies in SBS-IF patients have shown a decreased microbial diversity by using the relevant Shannon index of diversity as well as the emergence of highly resistant bacteria (121.,122.). Thus, prophylactic use should be avoided and antibiotics used only for strong clinical suspicion of SIBO, even if evidence-based treatment protocols are currently lacking.

Regarding the use of probiotics, two small randomized controlled trials (RCT) failed to demonstrate any effect of Lactobacillus rhamnosus on intestinal permeability and microbiota modulation in children with SBS (123.,124.).

Colonic Hypermetabolism and D-Lactic Acidosis

Clinical manifestations such as abdominal distension, bloating, and nausea, due to colonic microbiological hypermetabolism, may impair daily life and should be monitored. They may be the consequences of intestinal malabsorption leading to a high amount of undigested CHOs reaching the colon. This condition may be exacerbated by hyperphagia or aggressive tube feeding. One rare complication of colonic hypermetabolism, which is clearly different from SIBO, is D-LA (21.,125.-127.). This is due to Lactobacilli and other bacteria, including Clostridium perfringens and Streptococcus bovis, which, when present, ferment unabsorbed CHO to D-lactic acid, not metabolized by D-lactate dehydrogenase (128.). D-LA, that may also lead to D-lactate encephalopathy, is a rare neurologic syndrome that occurs in individuals with SBS or following jejuno-ileal bypass surgery (125.,129.). Neurologic symptoms include altered mental status with slurred speech and ataxia. Onset of neurologic symptoms is accompanied by metabolic acidosis and elevation of D-lactate plasma concentration. L-lactate concentration, which is reflected by serum lactate concentration is normal. Thiamine deficiency should be excluded (130.). The mechanism for the neurological symptoms is unknown. They have been attributed to D-lactate, but it is unclear if this is the cause or whether other factors are responsible (21.).

Diagnosis of D-LA is suspected from clinical symptoms and may be confirmed by assessing plasma, urinary, or stool D-lactic acid (21.,125.). In the already cited ERNICA survey 21 of 24 intestinal rehabilitation centers (87.5%) checked for D-LA (131.).

Treatments described in case reports have included watchful waiting (with spontaneous resolution), oral metronidazole, neomycin, vancomycin (for 10–14 days), and avoidance of “refined” CHO, while probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics have been used but without clear efficacy (132.-134.).

Peri-Anastomotic Ulcerations (PAU)

Peri-anastomotic ulceration (PAU), described a long time ago, is a rare potential life-threatening complication that may occur after intestinal resection (135.). The diagnosis is often delayed after a long-lasting history of refractory anemia (136.). The pathogenesis remains unknown and there are no established therapies (137.). It is most commonly described in children (138.,139.). The main symptom is bleeding, leading to iron-deficiency anemia, which can be life threatening. A survey reported a series of 11 patients (7 boys) with PAU after intestinal resection in infancy, focusing on predictive factors, medical and surgical treatment options, and long-term outcomes (138.). Capsule endoscopy may be very useful for the diagnosis of PAU (140.). No predictive factor (including the primary disease, the length of the remnant bowel, and the loss of the ICV) could be identified. Numerous treatment options, including antibiotics, probiotics (Saccharomyces boulardii), and anti-inflammatory drugs, proved to be ineffective to induce prolonged remission. Even after surgical resection, relapses were observed in 5 of 7 children. The mechanism leading to PAU remains unknown. Another series reported 14 cases revealed by severe anemia, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and growth failure in average 11.5 years after surgery (138.). Ulcerations were most often multiple (n = 11), located on the upper part of ileocolonic anastomoses (n = 12) and difficult to treat. No granulomas were seen but lymphoid follicules were frequent. In addition, either anti-saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (ASCA) or anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibodies (ANCA) were positive in 4 of 9 tested patients and 8 of 11 genotyped patients exhibited a NOD2 mutation (P < 0.0002 when compared to French healthy controls). Contrary to previous reports with limited follow-up, no medical or surgical treatment prevented recurrences. More recently, Fusaro et al (141.) reported 8 out of 114 children with SBS with PAU. Underlying causes of SBS were: 5 NEC, 2 gastroschisis, and 1 multiple intestinal atresias. The mean age at PAU diagnosis was 6.5 years with a delay before diagnosis of 35 months. All but 2 patients had PAU persistency after medical treatment. Endoscopic treatment (2 argon plasma coagulation; 1 platelet-rich fibrin instillation; 2 endoscopic hydrostatic dilations) was effective in 3 out of 5 children. Surgery was required in 3 patients. Since relapses may occur several years after discontinuation of PN, long-term follow-up is needed.

Renal Disease

PN induced renal disease remains debated. An old study involved 13 children aged of 9 ± 4.9 years who had been receiving total parenteral nutrition for 7.9 ± 4.1 years (142.). It reported a decreased glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of 65.5 ± 11.9 mL/min per 1.73 m2; range 49.5–83.7. Creatinine clearance was 69.1 ± 10.9 mL/min per 1.73 m2 without tubular damage (normal beta 2-microglobulinuria) nor nephrocalcinosis in all subjects. No relationship was seen between the true GFR and diagnosis, number of episodes of infections, or antibiotics used. The duration of PN was inversely correlated with the true GFR (r = −0.66, P < 0.01) (142.). More recent observations did not confirm such impaired renal function (143.-146.). However, cyclical PN may predispose to disturbed renal function by significantly changing the water-electrolyte homeostasis over each 24 hours period with intravascular volume depletion if there are also high intestinal fluid losses, hemodynamic instability episodes as well as repeated episodes of dehydration with hypercalcemia that might predispose to nephrocalcinosis or even renal failure (143.). The Toronto team reported a high incidence of nephrocalcinosis and/or increased echogenicity on ultrasound (US) (145.). However, these abnormalities had no impact on estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) or renal tubular function. A recent study concluded that despite the high prevalence of hypercalciuria, nephrocalcinosis was not common (144.). Many of these complications are avoidable with, for example maintenance of adequate hydration, regular surveillance of renal function and personalized adjustments of PN managed by a multidisciplinary nutrition support team (144.,146.). Base line and long-term monitoring of various aspects of renal function would be essential to characterize the effects of prolonged PN on kidney function. Follow-up into adulthood of long-term cohorts is required to evaluate the impact on different aspects of kidney functions later in life.

Metabolic Bone Disease (MBD)

As already mentioned in the nutritional monitoring chapter, children with IF and HPN are at higher risk of low bone mineral density (18.,25.,28.,147.). Since 2010, multiple studies have reported on bone status in IF. All studies agreed on a high risk of MBD for patients with IF on PN that persists after PN weaning (28.,148.,149.). This risk seems to be mostly related to calcium levels (150.,151.) and to growth failure (17.,152.) which is more prevalent in other forms of IF rather than in SBS (153.). Length of remnant bowel, higher PN dependency, and longer duration of PN do not seem to impact on MBD development (11.,146.). DXA monitoring for SBS-IF children should be promoted especially in presence of serum calcium, phosphorus, or parathormone alterations. SBS-IF children should be encouraged to have regular physical exercise and therapeutic options should be discussed with pediatric endocrinologists.

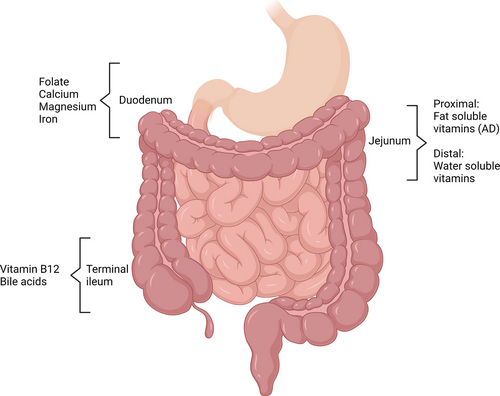

Micronutrient Deficiencies

Parenteral vitamins and micronutrients requirements are extensively addressed in the specific chapters of ESPGHAN-ESPEN PN guidelines (154.,155.), while monitoring can be found in the home PN chapter (156.). However, in the setting of SBS-IF, there is a difference in prevalence of micronutrient deficiency depending on the degree of PN dependency and patients can suffer from deficiency even after PN weaning (157.-159.). A retrospective cohort analysis focusing on only SBS children found vitamin D and zinc to be the most prevalent deficiencies during and after weaning PN (160.). In view of this evidence, vitamins trace elements should be regularly monitored both during and after PN weaning. Parenteral, enteral, or even sublingual supplements should be given when deficiency occurs and tailored according to residual intestinal anatomy and the absorption site and mechanism (161.-163.) (Fig. 3). In children with terminal ileum resection, fat soluble vitamins and vitamin B12 status should be monitored on a regular basis.

Specific absorption sites for vitamins and trace elements.

R5

-

If oral feeding is not possible, early oral stimulation and early follow-up by speech therapist/feeding unit should be provided.

-

Despite lack of robust evidence, antacid treatment (preferentially with PPI) should be considered for SBS children with symptoms of gastric hypersecretion or GERD.

-

There is insufficient evidence and little indications to promote the use of prokinetics drugs in motility disorders associated with SBS. A trial with those drugs may be restricted to children with important clinical GE reflux complaints or large gastric output volumes only under tight clinical evaluation.

-

There are no publications to date on use of antidiarrheal treatment in SBS children.

-

Based on panel’s expert opinion natriuresis should be monitored at least yearly for children with SBS on PN and even after PN weaning. This monitoring may be increased for children with small bowel stoma.

-

A policy of antimicrobial stewardship should be promoted for children with SBS: broad spectrum antibiotic prophylaxis should be avoided because of the high risk of bacteria selection and emergence of highly resistant bacteria.

-

Clinical assessment is the only tool for SIBO diagnosis since no other validated methodology is available.

-

D-LA clinical suspicion may be confirmed by plasma, urinary, or stool D-lactic levels.

-

PAU should be screened for in children with SBS suffering from unexplained anemia during PN supplementation or after PN weaning.

-

Regular clinical and biochemical follow-up is mandatory for SBS children with PAU diagnosis since there is high rate of recurrence.

-

Regular screening of renal function and annual abdominal US for nephrolithiasis screening is recommended for SBS children.

-

Laboratory testing of serum 25-OH vitamin D, calcium, phosphorus, alkaline phosphatase, parathormone, and urinary calcium should be undertaken every 6–12 months.

-

If calcium, phosphorus, and vitamin D levels are abnormal, a screening for MBD with DXA should be considered even after PN weaning.

-

Micronutrient levels should be tested regularly during PN (at least twice a year). This practice should be continued after PN weaning and should be tailored according to residual small bowel anatomy (eg, vitamin B12 if terminal ileum resection SBS type 1 and 2).

-

Micronutrient supplementation should be individualized according to micronutrient blood levels.

PP5

-

Family or social eating should be implemented for SBS children to prevent/improve oral aversion.

-

A SI follow-through (or other investigations if available/appropriate) radiological study should be performed for all PN dependent SBS children with obstructive symptoms and/or recurrent SIBO to evaluate intestinal structuring and/or dilation.

-

The possibility of SIBO or D-LA should be considered in SBS children with neurological symptoms associated with abdominal pain and worsening of diarrhea.

-

Gastrointestinal endoscopy aiming to reach the surgical anastomosis is the first choice for anastomotic ulcer diagnosis. When anastomosis is not reachable by conventional endoscopy, enteroscopy, or SI, video capsule should be considered.

TREATMENT FOR ENHANCING INTESTINAL ABSORPTION

Non-Transplant Surgery

Autologous gastro-intestinal reconstruction (AGIR) includes all those techniques that aim to increase intestinal absorption by remodeling dilated dysfunctional bowel, by increasing small bowel length, and by altering small bowel transit. By enhancing enteral absorption in patients affected by the SBS-IF (164.), these techniques have the added benefit of reducing PN dependency and its potential complications

Longitudinal intestinal lengthening and tailoring (LILT) was first introduced by Bianchi in 1980 (165.). The procedure remodels the dilated SI by longitudinal division along the mesenteric and antimesenteric borders to create 2 vascularized hemi-loops that are anastomosed isoperistaltically to the distal bowel for complete bowel continuity.

Serial transverse enteroplasty (STEP) was proposed by Kim et al in 2003 (166.) when a STEP Registry was also set up to aid long-term evaluation of outcomes. The procedure involves multiple alternating lateral transections of the dilated bowel leading to a longer zig-zag intestinal channel of reduced diameter.

Common to both LILT and STEP is a minimal requirement of bowel dilation of approximately 4 cm (167.). This correlates with evidence that a wider small bowel is associated with dysfunctional peristalsis with stasis and SIBO leading to local intestinal inflammation, septicemia, and IFALD (74.) with a potentially negative impact on PN weaning (168.). On the other hand, in the long term intestinal lengthening procedures have been shown to be effective in managing the problems associated with the bowel dilatation as a consequences of SIBO and IFALD (169.), thereby enhancing enteral absorption and weaning from PN. Some authors consider that a minimal length of 20 cm of dilated small bowel is necessary for conversion to total enteral nutrition following lengthening techniques (167.), in particular for LILT.

A retrospective study of 53 LILT procedures with a median follow-up of more than 6 years by a single center in Germany between 1988 and 2007, reported a 77% survival rate with 79% weaning from PN, however long-term growth follow-up information was lacking (170.).

Results from a retrospective multicenter registry for 97 STEP procedures from 50 centers in 13 countries, reported a 94% survival rate with 50% of patients weaning off PN (171.).

Shah et al compared the LILT and STEP. Based on retrospective data from 17 procedures (9 LILT, 6 STEP, and 1 LILT + STEP) (172.) there was no mortality and 56%, 14%, and 100% of PN weaning following LILT, STEP, and LILT + STEP respectively. A recent retrospective systematic review of 324 primary LILT and 377 primary STEP from 40 publications, attempted to compare the outcomes of the 2 procedures. There was a comparable PN weaning percentage of 52% versus 45%, and a mortality rate of 26% versus 7% for LILT and STEP (173.). It is relevant to state that the higher death rate in the LILT patients related to end-stage liver failure during the first 6 months of life is largely from IFALD development and not from the LILT procedure. Otherwise, the most prevalent surgical related complications were infection not otherwise specified (4%), re-dilation (4%), and gastrointestinal bleeding (3%).

A comparison of early (<375 days) and late (>375 days) complications was made in a multicenter retrospective study on 14 children, but did not discuss differences in PN weaning or mortality (174.).

A retrospective study compared SBS children who underwent tapering surgery (16) versus SBS children who did not (44) (175.). The results showed that the absence of the ICV was a risk factor, whereas a primary diagnosis of NEC was a protective factor against requiring tapering surgery. PN weaning rates were comparable at 75% in the tapering group and 86% for the non-tapering group.

More recently an innovative technique called Spiral Intestinal Lengthening and Tailoring (SILT) (176.) has been introduced. To date there have been 7 reported cases in the literature, with 2 weaned off PN (164.,177.,178.). The number of SILT cases is low with a short follow-up, such that it is not possible to offer clear indications for this technique. However, it is possible to suggest that SILT could be of potential benefit when LILT and STEP are not appropriate.

Single or multiple reversed (antiperistaltic) segment(s) can have a possible role in reducing transit time and increasing nutrient availability for absorption (179.,180.). Although not a new concept, the idea did not receive much attention or use. However, reversed segment(s) could be of benefit together with or following lengthening procedures, in tilting the balance in favor of increased absorption and weaning from PN (181.,182.).

R6

-

AGIR should be considered for children with SBS who are dependent on PN and when there is a small bowel dilation of >4 cm.

-

Evidence on the timing of surgery is lacking, and decisions are best made by a multidisciplinary team on a case-by-case basis.

PP6

-

LILT and STEP seem to have comparable outcomes, thus the choice should be made by the multidisciplinary team based on the anatomical situation and the surgeon’s experience.

Treatment to Increase Intestinal Absorption

Perhaps the most exciting recent advance in treatment of SBS-IF is the development of a GLP-2 synthetic analogue, teduglutide (TED) (183.), approved by the EMA for use in children. The treatment is helpful for the most seriously affected children with SBS-IF with long-term PN dependency for many months or years without demonstrating any evidence of intestinal adaptation and decreased PN dependency—even when stable and free of complications for >6 months. Previously these patients would have expected to remain on life-long PN or undergo intestinal transplant.

TED acts on the intestine to promote intestinal mucosal hypertrophy, inhibits gastric motility and acid secretion, improves intestinal blood flow, increases the intestinal barrier function, and enhances nutrient and fluid absorption (184.). Evidence for safety and efficacy of TED in children with SBS-IF (excluding those on other growth hormones, with malignancy or immunodeficiency, biologic therapy in last 6 months, or recent change in immunosuppressive treatment), has been shown in 2 phase III studies (16.,39.) a longer term “follow-on” study (184.) and a report on “real life” use (15.). The aim of treatment is to enable the child to tolerate >1 night or extra night per week off PN, that is, equivalent to a 20% reduction in PN. In the 24-week study 18 of 26, 69% patients treated with 0.05 mg/kg TED, the recommended dose, reduced PN > 20% compared to 1 of 9 (11%) of the standard of care group, P = 0.0036 (16.). The treatment was effective in some children with any of the major diagnoses that led to SBS-IF and in some children fully dependent on PN as well as in some children partially dependent. Most common adverse events were gastrointestinal (vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, stoma complication) and those associated with inter-current childhood infections (pyrexia, cough, headache) with similar incidence in standard of care cases and injection site reactions (16.).

TED was also well tolerated in 89 children treated for a median (range) of 51.7 (5.0–94.7) weeks. The safety profile was aligned with previous experience in adults and children (184.). When used outside a trial the outcome appeared even better with 12 of 17 patients achieving parenteral independence, irrespective of diagnosis: 3 patients after 3 months of treatment, 4 patients at 6 months, and 5 after 12 months (15.).

TED is currently approved in Europe for children >12 months of age with weight >10 kg. The current recommendation by specialist IF rehabilitation pediatricians is to reserve GLP-2 treatment for use in children managed by a specialist multidisciplinary IFR team who have plateaued in their intestinal adaptation, defined as inability to reduce PN by >10% even when stable for >3 months (185.). Children with initial loss of vascular access or progressive liver disease that might otherwise evolve to meet the criteria or who are already on the waiting list for intestinal transplantation (ITx) should be considered a priority for a trial of TED treatment in order to try to avoid the intestinal transplant (although some might still need a liver transplant).

Prior to commencing TED treatment an upper intestinal radiological contrast study is needed to exclude intestinal obstruction or significant intestinal dilatation and if detected surgical treatment should be considered prior to commencing treatment (39.). The infant/child should also have a negative fecal occult blood and if ≥10 years of age a colonoscopy to investigate for intestinal polyps. It would be usual practice for an IF center to have already done both upper and lower intestinal endoscopy in a child who was failing to wean from PN to exclude any mucosal disease that might be contributing to IF.

TED should only be prescribed for a child who would be expected to tolerate an increasing enteral nutrition. If the child normally eats s/he will need to be offered regular meals and snacks once on treatment. Nutrition advice from a specialist dietitian/other professional is important to ensure the best possible strategies are used to encourage a good dietary intake.

TED is administered by a daily, morning, subcutaneous injection. Parents/careers need to be taught to administer the injection. On commencing treatment regular weekly assessment is required for about 4 weeks to ensure PN is reduced in a timely fashion and complications such as fluid overload are avoided. Assessment frequency can then be reduced to fortnightly, 3 weekly, and eventually monthly (16.,39.). A discernible improvement in absorption can become apparent within 2 weeks of commencing treatment and PN volume (keeping the same formulation) should be reduced accordingly (usually in 10% increments) (16.).

Close monitoring of progress with regular attempts at reducing PN support (ideally in 10% increments) and trialing a night off PN at the earliest opportunity is needed. The current evidence is that some children can take as long as 12 months to wean off PN after starting TED treatment (184.).

In some patients in TED studies, treatment was stopped after 12 weeks. In some patients who had weaned off PN it needed to be restarted within <4 weeks of stopping treatment (39.), while others did not need to do so. However, longer-term outcome after stopping was not obtained.

There is currently an economic debate as to whether the cost of TED is greater than the costs of PN and management of complications (186.). However, if a child fully weans from PN the benefit to the child from losing their CVC and freedom from highly technical treatment with a near normal life expectancy would be expected to outweigh the cost. However, it is highly likely that alternative GLP-2 analogues, such as glepaglutide (187.) and apraglutide (188.) will also be available for children in the coming months and years that might alter the economic debate.

In summary, TED treatment can benefit children with SBS-IF of any etiology in whom intestinal adaptation has ceased for >3 months and who can tolerate enteral nutrition.

There are still some aspects of care that need to be established. These include:

-

The age and time post intestinal resection at which TED treatment is most effective.

-

How long to continue treatment if a child is failing to respond and is otherwise well.

-

Whether it is possible to reduce TED and even stop treatment in some SBS children once weaned off PN.

-

How to reduce treatment, for example would it be better to reduce the dose to alternate days or reduce the amount of each dose.

-

Early post-operative use has not been trialed to date. For example, TED might benefit a child within 3 months of the initial major SI resection or an intestinal lengthening procedure/autologous reconstructive surgery.

R7

-

TED at a dose of 0.05 mg/kg/day should be considered in metabolically stable children with SBS-IF in whom intestinal adaptation has plateaued even after appropriate investigation and treatment by a specialist pediatric multidisciplinary IF rehabilitation team.

-

Current recommendation does not allow the use of TED below 12 months of age and 10 kg.

-

TED is not an alternative to good multidisciplinary medical care.

-

Children with loss of initial vascular access and/or evolving liver disease should be prioritized in TED use.

PP7

-

Regular weekly monitoring including weight, urine output, blood urea, and electrolytes is needed for at least 4 weeks after starting TED and a week after any reduction in PN volume infused.

-

Regular meals and snacks (or if not tolerated, enteral tube feeds) need to be offered when weaning a child from PN with TED.

-

Teamwork between the child, parents/careers, and the multidisciplinary IF team professionals is essential to maximize the response to treatment.

-

More experience and an international consensus are needed for progressing the indications and timing of TED treatment.

Intestinal Transplant

Home PN is the first line of treatment in SBS-IF as it provides the best chance of long-term survival. If PN fails intestinal transplant needs to be considered.

Successful ITx was first reported in the late 1980s and proposed for the treatment of patients affected by irreversible intestinal failure (189.). In 2001, the American Society of Transplantation defined irreversible liver disease, exhaustion of central venous access sites, and recurrence of life-threatening situations (recurrent sepsis or dehydration) as indications to consider ITx for patients with IF (190.). Despite important surgical and medical advances in transplant techniques, reported long-term patients’ and grafts’ survival rates remains around 50% at 5 years for children (191.). In particular long-term survival seemed to be significantly lower for patients affected by ultra-SBS (70.).

From 2004, the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) promoted a prospective multicenter registry of patients on long-term PN for IF (192.). Long-term results revealed that PN-related liver disease was the only factor significantly affecting mortality of pediatric candidates for ITx (193.). Those results were confirmed by a 3-year prospective follow-up study on potential pediatric candidates for ITx in Japan (194.). Serum bilirubin levels >100 µmol/L seemed to negatively impact on post ITx survival (195.). It is an important observation that a quarter of patients referred to an IF multidisciplinary team for ITx work up for irreversible IFALD, eventually reversed their cholestasis with appropriate nutritional management (196.).

Loss of central vein access may stand as possible indication of pre-emptive ITx in SBS children since it could lead to “nutritional failure” (197.), even if alternative central vein management are possible in very experienced centers (198.).

The number of CVC-related septicemic episodes does not seem to impact on survival rate of patients on home PN in the ESPEN prospective registry (193.).

Two teams from the United Kingdom and United States reported their experience in isolated liver transplantation (LTx) in children with SBS collecting a total of 43 LTx in 39 patients with an overall survival rate of 64% at 5 years with 76% post-transplant PN weaning in the survivors (199.,200.). All candidates for LTx in those centers had a residual SI length ranging from 25 to 200 cm and an enteral intake of over 50% of caloric requirement prior to transplantation.

Other Care Options

In a small minority of patients either long-term PN treatment or SI transplant may not be the best option. For example, in children with other major organ failure in addition to SBS-IF continuing invasive treatment may prolong suffering without improving QoL (13.). The aims and objectives of treatment may need to be reconsidered taking into account the child’s best interests. In these specific cases invasive treatment such as continuing PN or proceeding to intestinal transplant may raise medical and ethical dilemmas for which comprehensive discussion with parents, patients, and involved specialists are needed. If a home PN and ITX are not in the child’s best interests it is important to involve a symptom care/palliative care team and if necessary, make an “end of life” care plan (201.).

R8

-

Combined liver-intestinal transplant for children with SBS-IF should be considered as life-saving option only in cases of irreversible IFALD.

-

SBS children with >2 central venous line thromboses should be referred to a multidisciplinary team which includes an intestinal transplantation unit for a case-by-case discussion of a possible pre-emptive ITx.

-

In cases of irreversible IFALD in SBS children with high potential for PN weaning, isolated liver transplant could be considered.

-

In exceptional patients with additional major organ failure aims and objectives of treatment may need to be different to other SBS-IF patients to act in the child’s best interest.

PP8

-

SBS children on long-term PN with signs of liver disease (serum bilirubin >50–100 µmol/L—3–6 mg/dL and/or platelets < 100,000), in absence of infection, and on >1 blood sample at least 2 weeks apart should be evaluated by multidisciplinary team involving ITx specialists.

-

In a small minority of severely impaired children with additional organ failure an ethical discussion should be held and an appropriate care plan made.

RESEARCH GAPS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

The concept of individualized care for children with SBS-IF has been made clear throughout the whole paper. In order to achieve this important goal future research should address:

-

Individual energy and micronutrients requirements according to different remnant small bowel anatomy and the individual child’s absorptive capacity.

-

Longitudinal body composition assessment to define the appropriate needs to achieve the best growth trajectory.

-

Long-term follow-up after PN weaning to identify early predictors of poor growth and pubertal retardation.

As outlined from the discussion in this position paper:

-

How to prevent long-term PN complication in order to avoid failure of PN treatment and the need for life-saving ITx?

-

How to increase intestinal absorption of the remnant small bowel in order to gain intestinal sufficiency?

-

Do we have a safer option to propose instead of ITx for definitive nutritional failure?

We previously reported the great progress made in the latest century in addressing the first question. Recent discovery of farnesoid X receptor (FXR) as a possible target mediating altered bile secretion in SBS patients (202.) has opened a new field of research for IFALD prevention. Unfortunately, studies on FXR agonists for SBS syndrome are limited to a preclinical phase and showing conflicting results (203.,204.).

TED is probably the biggest revolution in the world of SBS so far. The main issue with this GLP-2 analogue is that it has very short half-life. For this reason, researchers have focused their interest on new GLP-2 long acting GLP-2 analogues (187.,188.). Results of phase II trial in adult SBS have been published for both molecules (187.,205.). Phase III trials are ongoing and registered on clinicaltrials.gov but not yet recruiting pediatric patients.

From the more surgical point of view, we reviewed non-transplant and transplant option available, however they are not always effective and safe. The most promising new frontier and opportunity for research in this field seems to be represented by the intestine’s own capacity for regeneration and the creation of a tissue-engineered SI from stem cells (206.).

CONCLUSIONS

In the 2 chapter of this position paper the ESPGHAN Committee of Nutrition summarized all the available evidences of the management of children with SBS from bowel resection until PN weaning. The best follow-up of those fragile patients in order to promote intestinal absorption and prevent SBS complications should be tailor made on a case by case basis by a multidisciplinary IR team.