Airway Complication After Thyroid Surgery: Minimally Invasive Management of Bilateral Recurrent Nerve Injury†

Supported by the Hungarian Scientific Council (ETT:13-111/98).

Abstract

Objectives: After bilateral vocal cord paralysis, the consequent paramedian position usually necessitates tracheostomy for at least 6 months, when the paralysis is potentially reversible. In the present study a reversible endoscopic vocal cord laterofixation procedure was used instead of tracheotomy.

Study Design: Prospective study of 15 consecutive patients aged 33 to 73 years who suffered bilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis after thyroid surgery.

Methods: The operation was performed endoscopically with a special endo-extralaryngeal needle carrier instrument. Two ends of a monofilament nonresorbable thread were passed above and under the posterior third of the vocal cord and knotted on the prelaryngeal muscles, permitting the creation of an abducted vocal cord position. If movement of one or both vocal cords recovered, the suture was removed. Regular spirometric measurements and radiological aspiration tests were conducted on the patients.

Results: During the follow-up period of 3 to 40 months, airway stability was demonstrated in all but one patient. After the repeated lateralization procedure, this patient's breathing improved. Partial or complete vocal cord recovery was observed in eight patients. In six patients further voice improvement was achieved when the threads were removed after vocal cord medialization or recovery. Mild postoperative aspirations ceased in the first postoperative days.

Conclusions: This management approach offers an alternative to tracheostomy in the early period of paralysis, avoids terminal loss of voice quality, and provides a “one-stage” solution for permanent bilateral recurrent nerve injuries.

INTRODUCTION

Vocal cord paralysis remains a complication of thyroid surgery.1, 2 More than 50% of the paralysis is transient1-3 because intraoperative damage commonly results in reversible neuropraxic injury rather than complete transsection of the recurrent nerve. Although animal experiments have demonstrated that atrophy of the laryngeal muscles becomes irreversible after 7 months of inactivation,4 clinical observation has shown that it is worth waiting 6 to 12 months for spontaneous recovery of vocal cord function.

Bilateral injury most often results from reoperation or operation on malignant tumors.2, 3, 5 The magnitude of the dyspnea depends on the position of the paralyzed vocal cords and on the cardiopulmonary reserve, but often patients cannot be extubated after surgery. According to the literature6, 7 and in our own experience, the common vocal cord lateralization techniques (including arytenoidectomy with or without cordectomy and transverse cordotomy) cause drastic irreversible damage to the larynx and phonation. The long-term success of the theoretically superior reinnervation procedure has been about 80%, but reinnervation requires a delay of 4 to 6 months after surgery before active abduction may begin.7 Thus most patients must be tracheostomized for 6 to 12 months, with all the possible somatic and psychological side effects. The most significant side effects are intraoperative and postoperative hemorrhage, risk of wound infection, especially when immediately after thyroid surgery, and the complications of tracheomalacia and tracheal stenosis due to scarring. Finally, this procedure increases the cost and length of hospital stay and ambulatory care. Hence, in cases when suffocation presents only on exertion, the “watch and wait” policy is often preferable to tracheostomy, although this approach may restrict the patient's daily activities.

Articles were published in the early 1990s about a reversible, simple exo-endolaryngeal suture technique for the “acute” lateralization of the vocal cord to provide an immediate stable airway for patients with bilateral vocal cord paralysis.5, 8, 9 This method not only eliminated the need for tracheostomy but also afforded a favorable solution in terms of function: if contralateral vocal cord function recovered, the fixed vocal cord could be released. Despite promising early results, this concept has not been accepted. According to Tucker,7 the major drawback of this simple procedure is that in many cases it does not yield adequate improvement. To solve this problem we suggested10 inserting the laterofixing suture in cases of early vocal cord lateralization by using a modification of Lichtenberger's endo-extralaryngeal technique.11, 12 We found that this procedure provided a stable airway in the critical early period, but no data existed on the effect of laterofixation on the vocal cord after recovery or on the procedure's long-term efficacy. We now report on our 3-year experience with the refinement of this technique.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

Fifteen consecutive patients (14 women and 1 man) were operated on for bilateral vocal cord paralysis within 6 months after thyroid surgery from June 1996 to April 1998 (Table 1). The age of the patients ranged from 33 to 73 years. Follow-up was between 3 and 40 months (mean, 17 mo). The thyroid surgeries were performed previously in the referring general surgery departments of the Albert Szent-Györgyi Medical University. Two patients had undergone thyroid operation for recurrent malignant tumor, three had had reoperation of a benign lesion, and the remaining patients had had subtotal strumectomy for benign diseases of the thyroid (8 patients) and parathyroid (2 patients). The time between the onset of paralysis and the laterofixation procedure ranged from 2 days to 122 days (mean, 23 d). In six cases the patient could not be extubated after the thyroid surgery; four of these patients were reintubated and two were tracheostomized before they were sent for the vocal cord lateralization procedure at our clinic. The other nine patients had moderate to severe stridor at rest and severe stridor on exertion (Fig. 1A). Among the five patients who had undergone reoperation of the thyroid gland, three had laryngoscopically proved unilateral vocal cord paralysis before reoperation. After receiving accurate information about the possibility of worsening voice quality, all of the patients chose vocal cord lateralization instead of tracheostomy.

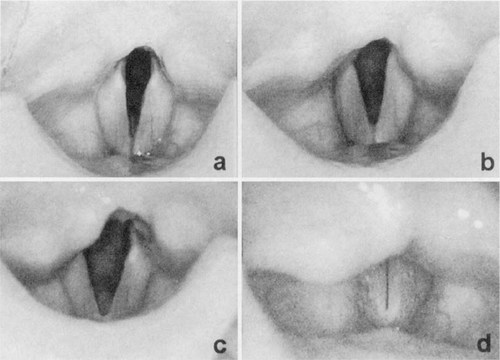

A. Bilateral vocal cord paralysis (patient 11, forced inspiratory volume during the first second (FIV-1): 0.9 L). B. The right vocal cord is placed in paramedian position (first postoperative first month, FIV-1: 1.8 L), C. The vocal cords recovered (second postoperative month, FIV-1: 2.3 L). The abduction of the right vocal cord also improved despite the laterofixing suture. D. Stationary stroboscopic photography after removal of the laterofixing suture: the glottic closure and the voice completed (digitized video pictures).

Surgical Technique and Postoperative Care

The endo-extralaryngeal suture technique was first described by Lichtenberger11 for laryngeal stenosis. We modified the original method. In our study two surgeons conducted the operation. The procedure was performed under general anesthesia (a Rüsch tube was introduced for translaryngeal intubation in four patients, trans-stomal intubation was carried out in four patients, and supraglottic low-frequency JET ventilation was carried out in nine patients). A Kleinsasser or Weerda laryngoscope was used to open up the glottic space. After this, the endoscopist passed one end of a monofilament, nonresorbable thread (#2-0 or 0 Prolene) under the posterior third of the vocal cord using Lichtenberger's needle carrier instrument.11 The other end was passed above the vocal cord across Morgagni's ventricle out to the surface of the neck. The thread formed a loop around the vocal process, permitting the creation of an abducted vocal cord position. The level of the abduction-and the postoperative width of the glottis-could be controlled correctly by the endoscopist, if JET ventilation was used for the anesthesia or if the patient was intubated trans-stomally. The assistant surgeon made an approximately 10-mm-long incision between the two ends of the thread, then pulled back both ends under the skin with a Jansen hook, and tied a knot above the prelaryngeal muscles (not on the thyroid ala, as originally suggested by Ejnell et al.9 and Lichtenberger11). The wound was closed with one or two sutures.

The patients received intravenous steroid (methylprednisolone 40-500 mg twice daily) until the first or second postoperative day. In the next 4 to 5 days aerosol steroid was administered (beclomethasone 100 μg three times daily). A wide-spectrum antibiotic (cefuroxime 250-500 mg twice daily) was used in the first 5 postoperative days.

Spirometric Measurements and Follow-up

Preoperative and postoperative airway function tests and videolaryngoscopy were conducted on each of the patients. Measurements were made before the laterofixation procedure (when possible) and on postoperative days 1 through 5. The follow-up examinations were made from 2-week to 1-month intervals in the first year to detect vocal cord recovery as soon as possible. Radiological examination of the aspiration was performed in 13 patients at the end of the first postoperative month.

RESULTS

After unilateral vocal cord laterofixation, each patient awakened without difficulty and the two previous tracheotomies were closed immediately. Severe postoperative edema was found in only three cases, but they could be managed without reintubation or tracheotomy. The spirometry performed on postoperative days 1 to 5 revealed a marked increase in forced inspiratory volume during the first second (Fig. 1 B).

Patients 1 and 4 were found to have mild medialization in cord position during the first 3 months after surgery. Concurrently, these patients' spirometric values worsened somewhat. However, this change was not significant, the positions of the cords and the spirometric values stabilized, and no dyspnea was noted. Marked medialization presented only in patient 3, after a kidney transplantation that was performed 2 weeks after the laterofixation procedure. After a repeated lateralization procedure on the same side, the patient's breathing improved, but she died 3 months later from complications of the transplantation. An elderly patient died in the 14th postoperative month from an intercurrent disease. One patient was lost to follow-up, but she has been symptom free so far according to information gained from her general practitioner. For the remainder of our patients, their airways have been stable during the follow-up (Fig. 2).

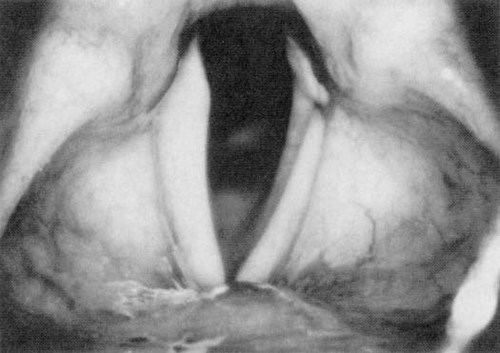

The larynx of a 70-year-old woman (patient 5) in the 24th postoperative month. The left vocal cord is placed in full abduction (FIV-1: 1.4 L). The epithelized lateralizing suture can be seen.

However, the patients' dysphonia grew significantly worse after surgery, and their voices became hoarse and weak. The contralateral vocal cord started to move 1 to 5 months after the laterofixation in seven patients and complete recovery followed in five of these patients within a further 2 to 7 weeks. After careful evaluation of breathing function, larynx size, and general condition, we decided to release the fixed cord in four patients. One other suture was removed later from one elderly patient in the 89th week because inflammation presented around the suture. Her breathing remained stable, because of the subsequent further improvement of the contralateral vocal cord movement. Significant vocal cord medialization was observed up to 2 weeks after these procedures. Movement was also re-established in one of these previously laterofixed cords (Fig. 1). The recovery of one laterofixed vocal cord was detected in the 8th postoperative month (the contralateral side remained paralyzed). The vocal cord adduction movement improved after the removal of the fixing suture. The voice quality of these patients significantly increased proportionally by the medialization or recovery of the vocal cords.

Swallowing on the side of the laterofixation was painful for all patients and mild aspiration was observed in some cases in the first postoperative days. No patient showed aspiration later either clinically or radiologically during follow-up and no further complications occurred. The thread cut into the substance of the vocal cord and the mucosa above it epithelialized approximately 10 days from the surgery. Granulation did not occur in the larynxes.

DISCUSSION

The advantage of the endo-extralaryngeal suture technique compared with the exo-endolaryngeal techniques is clear: the fixing thread can be inserted more easily and precisely with Lichtenberger's needle carrier, which was constructed especially for endo-extralaryngeal sutures. But the use of this instrument in itself did not provide the improved results hypothesized in our series. In three of our first four patients, in whom the combination of Kleinsasser laryngoscope and intubation was used for the surgery,10 more or less severe spontaneous medialization was observed in the first postoperative months. For this reason we revised our endoscopic surgery technique in some respects.

In our series the combination of the supraglottic JET ventilation and the Weerda laryngoscope provided the best way to maneuver with the needle carrier instrument in the larynx when the patient had not been previously tracheostomized. So proper thread insertion becomes possible just around the vocal process; in our experience, this is possibly the key factor of these simple lateralization procedures. The vocal process provides a more stable surface for the thread than the membranous part of the vocal cord, so postoperative medialization can be reduced. A further advantage of the correct suture insertion is that the anatomical structure of the vocal fold remains intact, which is important as concerns later voice function.6

In terms of long-term effectiveness, whether the fixing thread cuts into the vocal cord substance or the prelaryngeal muscles is significant. The use of a wider thread (Prolene 0 instead of the Prolene 2-0 originally suggested10) might also play a role in the fact that medialization decreased to less than 0.5 to 1 mm in the last 11 patients, as evidenced by the stable inspiratory values for these patients (Table I). In our series the muscles provide an appropriate “flexible” base for the fixing thread. Atrophy of the cartilage is thus avoided and the use of an external silicone platelet is not necessary.13 Because access to the thyroid ala is not necessary, in our experience the whole operation takes approximately 10 to 15 minutes.

At the beginning of this study the selection of the side to be operated appeared to be a cardinal question. In another group of patients who suffered from posterior glottic stenosis and who were operated on by a similar lateralization technique, we found that laterofixed cord movement can be detected by careful observation.14 Improvement of vocal cord abduction movements was detected in patients 10 and 11 (Fig. 1B and C) despite the laterofixation sutures. Laryngeal electromyography15 might also be a useful tool for detecting this recovery in questionable cases. Obviously, laterofixation should be performed on the side where paralysis is irreversible or where the nerve injury is presumably more severe (due to nerve infiltration by tumor, resection, and so forth). A previous nerve injury in their history clearly indicated the side of the laterofixation in three patients.

This method is minimally invasive and the generally moderate postoperative edema can be controlled effectively by a combination of intravenous and inhaled steroids, so an appropriate airway can be achieved even in the first postoperative days. The endolaryngeal over-epithelization of the thread takes approximately 10 days, so the use of a wide-spectrum antibiotic is suggested to prevent the spread of bacterial infection from the larynx into the deeper layers of the neck.

Airway resistance decreases more than linearly by enlargement of the diameter in cases of upper respiratory tract stenosis. Other determining factors, such as the narrowing effect of the inspiration on the paralyzed glottis (Bernoulli's effect) and the turbulence, also decrease concurrently with the deceleration of the flow.16 Therefore, the relatively smaller enlargement of the glottis leads to a significant decrease in laryngeal resistance. Supraglottic JET ventilation provides an excellent evaluation of the glottic diameter, thus it becomes possible during surgery to determine individual glottis width (depending on the patient's larynx size, cardiorespiratory state, profession, and so forth). Thus the postoperative voices of our patients became weaker-in inverse proportion to the adequacy of the airway achieved-but socially acceptable in most cases. Ejnell et al.9 reported similar findings.

Clinical observation demonstrates that temporary laterofixation of the vocal cord can be done without causing any lasting damage if the thread is removed within 10 weeks.5 In our series the patients' voices improved due to more or less overcompensation at phonation after the recovery of contralateral cord mobility. In cases in which the fixing thread was removed, the vocal cord position became more medial. This might happen as much as 2 years after surgery, resulting in further voice improvement, as evidenced by patient 7. The small phonation gap, which remained at the site of the suture in the posterior glottic chink, had no significant influence on voice quality. According to the patient, complete restoration of the preoperative voice was achieved when recovery was bilateral (Fig. 1D). In the case of a late (more than 6-8 mo) removal of the fixing suture, the immediate results might not be as impressive, as in the case of patient 13. Muscle fibrosis,4 development of pathological voice production (false vocal cord phonation, and so forth), and only partial reinnervation may have played a role in this case. Speech therapy was effective, but this fact suggests the need for the removal of the fixing suture as soon as possible. In case of a patient with small larynx and with poor cardiorespiratory status or only partial vocal cord recovery, fixed cord mobilization must be evaluated individually.

In contrast to early laterofixation, the similar simple laterofixation in patients several months after the onset of paralysis has not always been satisfactory.7, 13, 17 We assume that the continuous tension produced by a fixed arytenoid joint causes the fixing thread to cut through the vocal cord substance, resulting in medialization. In contrast, a mobile arytenoid cartilage can be easily rotated in the early period, which is an important fact in carrying out the vocal cord laterofixation procedure as soon as possible.

Most of our patients were able to return to their previous lifestyles without difficulty after a short period of time. There were no significant complaints as concerns swallowing. The absence of aspiration probably can be explained by the intact sensorial innervation of the larynx. A similar experience was reported by Geterud et al.17

CONCLUSION

Our experience suggests that early endo-extralaryngeal vocal cord laterofixation provides a reliable alternative for treating patients with bilateral vocal cord paralysis. This procedure is reversible to a large extent, so the vocal cord function is not sacrificed entirely. The most significant feature, however, is that recovery of cord mobility can be expected without the need for tracheostomy, and it might provide a one-stage solution to the problem of suffocation when the bilateral recurrent nerve injury has proved to be permanent.