Evaluation of different strategies for identifying asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction and pre-clinical (stage B) heart failure in the elderly. Results from ‘PREDICTOR’, a population based-study in central Italy

Abstract

Aims

To evaluate the accuracy and cost-effectiveness of different screening strategies to identify systolic and/or diastolic asymptomatic LV dysfunction (ALVD), as well as pre-clinical (stage B) heart failure (HF), in a community of elderly subjects in Italy.

Methods and results

A sample of 1452 subjects aged 65–84 years were chosen from the original cohort of 2001 randomly selected residents of the Lazio Region (Italy), as a part of the PREDICTOR survey. All subjects underwent physical examination, biochemistry/NT-proBNP assessment, 12-lead ECG, and Doppler transthoracic echocardiography (TE). Five strategies were evaluated including ECG, NT-proBNP, TE, and their combinations. Subjects older than 75 years, and with at least two additional risk factors, were defined as being high-risk for HF (435), whereas the remaining 1017 were defined at low risk. Screening characteristics and cost-effectiveness (cost per case) of the five strategies to predict systolic (EF <50%) or diastolic ALVD and pre-clinical HF (stage B) were compared. NT-proBNP was the most accurate and cost-effective screening strategy to identify systolic and moderate to severe diastolic LV dysfunction without a difference between the high-risk and low-risk groups. Adding ECG to the NT-proBNP assessment did not improve the detection of pre-clinical LV dysfunction. TE-based screening was the least cost-effective strategy. In fact, all screening strategies were inadequate to identify stage B HF.

Conclusions

In a community of elderly people, NT-proBNP is the most accurate and cost- effective pre-screening strategy to identify systolic and moderate to severe diastolic LV dysfunction.

See page 1077 for the editorial comment on this article (doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hft136)

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is an issue of public health concern. Its overall prevalence continues to rise in developed countries, particularly in the elderly.1,2 It is a progressive disease with a pre-clinical phase (stage B HF) characterized by the presence of structural and/or functional cardiac abnormalities that precede the development of the overt disease.1–3 Stage B HF includes asymptomatic subjects with previous acute myocardial infarction (AMI), LV post-AMI remodelling, hypertensive LV hypertrophy (LVH), pre-clinical (asymptomatic) LV dysfunction (ALVD) (either systolic and/or diastolic), and valvular heart disease (VHD).1,3,4

The prevalence of both clinical and pre-clinical HF increases with age.4–11 In most community studies, the elderly showed a high prevalence of systolic and diastolic AVLD,8–13 as well as of pre-clinical HF (stage B).10 Since early and appropriate pharmacological intervention has been shown to be effective in preventing or at least slowing the clinical course of the disease from pre-clinical to clinical HF,14,15 screening strategies have been advocated especially for high-risk subjects.16–24

Previous studies have reported the accuracy and cost-effectiveness of BNP, NT-proBNP, and/or 12-lead ECG over Doppler transthoracic echocardiography (TE) in screening people at high risk of HF both in the community and in clinical settings;18–22 however, no study has specifically addressed the elderly. The present study aimed to assess the accuracy and cost-effectiveness ratio of ECG, NT-proBNP, and their combinations with Doppler TE, in screening for systolic and diastolic ALVD and stage B HF in randomly selected elderly subjects from an urban Italian community with different levels of risk.

Methods

Population recruitment and assessment

From July 2007 to January 2010, a sample of 2001 subjects aged 65–84 years, residents in the Lazio region (Italy) in central Italy, were randomly selected from the Regional Health Registry as a part of the PREDICTOR survey. All subjects underwent a physical examination, NT-proBNP assessment, 12-lead ECG, and a complete Doppler TE examination.11

Definition of high risk

High risk was defined as the presence of at least two concomitant risk factors (RFs): arterial hypertension (AH), type-2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), previous coronary heart disease (CHD) or AMI, VHD more than mild, permanent AF, previous use of cardiotoxic drugs, peripheral vascular disease including asymptomatic carotid vascular disease, stroke, or transient ischaemic attack (TIA), and renal dysfunction defined as serum creatinine >2 mg/dL or as an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60 mL/min/1.73 m2.1,3,4,11,22

Natriuretic peptide

Measurements of NT-proBNP were made blind in fasting blood samples with an electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (Elecsys 2010, Roche Diagnostics GmbH) in a central laboratory as previously reported.11 It was defined as abnormal if it fell above the upper reference level (<95th percentile of normal distribution, >278 pg/mL) in the whole normal population of the PREDICTOR study, including healthy subjects free from cardiovascular disease, with normal ECGs and TEs, and free from renal disease (Table 1).

| Females (≤74 years) | Males (≤74 years) | Females (≥75 years) | Males (≥75 years) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median NT-proBNP levels (IQR) (pg/mL) | 83.5 (42–124) | 52.5 (30–87) | 150 (87–284) | 83 (59–170) | 68 (39–120) |

| NT-proBNP upper reference levels (95th percentile of NT-proBNP concentration) (pg/mL) | 225 | 169 | 810 | 312 | 278 |

| Number of subjects with NT-proBNP above 95th percentile. | 76 | 92 | 18 | 25 | 211 |

- a IQR, interquartile range.

Electrocardiography

Twelve-lead ECGs were obtained from all subjects and centrally analysed. LVH was defined as SV3 + RaVL >2.8 mV in men or >2.0 mV in women or as the presence of LV strain as previously reported.25 The ECG was defined as abnormal in the presence of the following conditions: AF, Q waves indicating previous MI, LVH, LV strain, or LBBB.

Echocardiography

The echocardiographic protocol of the PREDICTOR study has been described previously.11

Briefly, a complete Doppler TE was performed on all participants in peripheral centres, recorded in DICOM format, and sent to the Core Lab for centralized reading.11 The LVEF was calculated either from the LV linear measurements or from the apical four-chamber view using the modified Simpson's rule method.26 Doppler-derived indexes of transmitral flow and pulmonary vein flow, and tissue Doppler imaging of the lateral mitral annulus (E/e) were used to define diastolic LVD, as previously reported.27,28

Systolic LVD was defined as LVEF <50%. Diastolic function was defined as abnormal if at least three of the following conditions were satisfied: E/A ratio <0.75 or >1.5; deceleration time of E velocity <140 ms or >280 ms; pulmonary vein (PV) peak systolic velocity <PV peak diastolic velocity; PV a wave duration – mitral A wave duration difference <0; and E/e' >8, and graded as mild, moderate, or severe based on a Doppler-derived multiparametric algorithm.11 When fewer than three diagnostic criteria were recognized in the case of discordant parameters, or when an equal number of criteria were recognized for more than one category of diastolic function, diastolic LVD was defined as indeterminate.

Subjects with LVD, but without a history or clinical evidence of HF, were considered to have ALVD (systolic or diastolic)11 (Table 2).

| Condition | Definition | Prevalence, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| LV hypertrophy° | LV mass >95 g/m2 (women); >115 g/m2 (men) | n = 86 (5.9) |

| LV dilatation | EDV >95 mL/m2 | n = 1 (0.1) |

| Concentric remodelling | Relative wall thickness >0.42 | n = 544 (37.5) |

| AVLD | Systolic and/or diastolic LVD and absence of clinical signs and/or symptoms of HF (NYHA class I) | n = 612 (42.1%)* |

| Systolic ALVD | EF <50% and absence of clinical signs and/or symptoms of HF (NYHA class I) | n = 22 (1.5) |

| Diastolic ALVD | Echocardiographic diagnosis of diastolic dysfunctiona and absence of signs and/or symptoms of HF (NYHA class =1) | n =607 (41.8) |

| Previous cardiovascular disease | Positive case history for myocardial infarction, stroke, aortic disease, or peripheral vascular disease | n = 387 (26.7) |

| Valvular disease | Mitral or aortic regurgitation (more than mild) | n = 43 (2.3) |

| Subjects classified as in stage B HF | Structural and/or functional cardiac abnormalities without clinical signs and/or symptoms of HF | n = 945 (65.1) |

- a ALVD, asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction; EDV, end-diastolic volume; HF, heart failure.

- a Five persons showed systolic LVD with normal diastolic LV function.

Stages of heart failure

Pre-clinical stages of HF were assessed by matching clinical history information obtained by the case report form and the echocardiographic data.1 Stage A HF was diagnosed if cardiovascular (CV) RFs such as AH, T2DM, obesity, or metabolic syndrome (METs, ATP-III criteria) were detected, or in the presence of a documented clinical history of atherosclerotic disease or a positive case history for use of cardiotoxins, without evidence of structural heart disease and any signs or symptoms of HF.11 Stage B was diagnosed in the presence of ALVD and/or a structural heart disease detected at TE, or of a positive clinical history for CV disease or VHD in the absence of clinical signs or symptoms of HF11 (Table 2).

Screening strategies

The five screening strategies simulated in the current study are shown in Table 3. Since Doppler TE is considered the reference method to detect systolic and diastolic LVD as well as the presence of structural LV abnormalities (LV dilatation, LVH, or VHD), strategy 1 (all subjects undergo Doppler TE) was defined as the gold standard strategy.

| Strategies | |

|---|---|

| Strategy 1 | All subjects to undergo transthoracic Doppler echocardiography (TE) (gold standard strategy). |

| Strategy 2 | All subjects to undergo 12-lead ECG. Those subjects with abnormal ECG to undergo TE. |

| Strategy 3 | All subjects to undergo plasma NT-proBNP measurement. Those subjects with elevated NT-proBNP to undergo TE. |

| Strategy 4 | All subjects to undergo 12-lead ECG and NT-proBNP measurement. Those subjects with ECG abnormal and elevated NT-proBNP to undergo TE. |

| Strategy 5 | All subjects to undergo 12-lead ECG and NT-proBNP measurement. Those subjects with ECG abnormal or elevated NT-proBNP to undergo TE. |

Statistical analysis

The accuracy and cost-effectiveness of the five screening strategies were evaluated in the whole population, and in the high-risk group by using the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses. Two-sided tests were used to compare categories. The screening characteristics and cost-effectiveness of the five screening strategies, defined as the cost per-case of LVD found, were compared for each group (Table 3). The costs of each screening component were obtained from the Lazio regional price tables (revision 18 October 2011) and expressed in euros (Doppler TE, €61.97; 12-lead ECG, €11.62; NT-proBNP, €9.14; clinical visit, €13.60). Data were analysed using IBM SPSS 18 Software (Armonk, US). The comparison of the area under the ROC (AUROC) was made with the STATA 10 statistical program (StataCorp LP, TX, USA). The statistical significance test for the comparison of two AUROCs was applied setting a type I error probability of 0.05.29

Results

Demographics

The study subjects are depicted in Figure 1. Of the 2001 subjects in the original PREDICTOR cohort, 549 were excluded for various causes. Among the total 1452 subjects included in the present post-hoc analysis, 435 were at high risk and 1017 at low risk. The prevalence of systolic AVLD did not differ between high-risk and low-risk groups. Diastolic ALVD and stage B HF were more prevalent in the high-risk subgroup than in those at low risk or in the whole population (P = 0.010 and P < 0.0001, respectively). Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 4. As expected, high-risk subjects were older and had a higher prevalence of RFs, AF, previous CHD, or CV disease, and renal failure compared with low-risk subjects. The groups did not differ in terms of gender distribution or use of cardiotoxins.

| Total population | Low risk (0–1 RFs) | High risk (≥2 RFs) | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| No. of subjects | 1.452 | 100 | 1.017 | 70.0 | 435 | 30.0 | |

| Age ≥75years | 469 | 32.3 | 287 | 28.2 | 182 | 41.8 | <0.01 |

| Males | 726 | 50.0 | 496 | 48.8 | 230 | 52.9 | 0.152 |

| Coronary heart disease | 95 | 6.5 | 14 | 1.4 | 81 | 18.6 | <0.01 |

| Arterial hypertension | 816 | 56.2 | 415 | 40.8 | 401 | 92.2 | <0.01 |

| Valvular disease (more than mild) | 34 | 2.3 | 2 | 0.2 | 32 | 7.4 | <0.01 |

| Type-2 diabetes mellitus | 232 | 16.0 | 56 | 5.5 | 176 | 40.5 | <0.01 |

| Atrial fibrillation (permanent) | 12 | 0.8 | 2 | 0.2 | 10 | 2.3 | <0.01 |

| Positive case history for use of cardiotoxins | 4 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.1 | 3 | 0.7 | 0.065 |

| Peipheral artery disease | 60 | 4.1 | 11 | 1.1 | 49 | 11.3 | <0.01 |

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 82 | 5.6 | 4 | 0.4 | 78 | 17.9 | <0.01 |

| Renal failure (eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2) | 262 | 18.0 | 63 | 6.2 | 199 | 45.7 | <0.01 |

- a P-values are for differences between the low- and high-risk subgroups.

- b eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Accuracy of screening strategies

The results of different screening approaches using ECG, NT-proBNP, or their combination in detecting systolic ALVD (EF <50%), moderate to severe diastolic ALVD, and stage B HF in the high-risk group and in the whole study population are shown in Table 5.

| Screening strategies | High-risk population (435) | Whole population (1452) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy 1 | Transthoracic echo (gold standard) | LV systolic dysfunction (EF <50%) | |||||||

| (n = 6) | (n = 22) | ||||||||

| Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | PPV (95% CI) | NPV (95% CI) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | PPV (95% CI) | NPV (95% CI) | ||

| Strategy 2 | ECG abnormal | 66.67 (28.9–104.4) | 86.01 (82.7–89.3) | 6.25 (0.3–12.2) | 99.46 (98.7–100.2) | 40.91 (20.4–61.5) | 90.63 (89.1–92.1) | 6.29 (2.3–10.3) | 99.01 (98.5–99.5) |

| Strategy 3 | Elevated NT-proBNP (>278 pg/mL) | 100.00 (100.0–100.0) | 81.12 (77.4–84.8) | 6.90 (1.6–12.2) | 100.00 (100.0–100.0) | 63.64 (43.5–83.7) | 89.44 (87.8–91.0) | 8.48 (4.2–12.7) | 99.38 (98.9–99.8) |

| Strategy 4 | ECG abnormal and elevated NT-proBNP | 66.67 (28.9–10.4) | 95.57 (93.6–97.5) | 17.39 (1.9–32.9) | 99.51 (98.8–100.2) | 31.82 (12.4–51.3) | 97.90 (97.2–98.6) | 18.92 (6.3–31.5) | 98.94 (98.4–99.5) |

| Strategy 5 | ECG abnormal or elevated NT-proBNP | 100.00 (100.0–100.0) | 71.56 (67.3–75.8) | 4.69 (1.0–8.3) | 100.00 (100.0–100.0) | 72.73 (54.1–91.3) | 82.17 (80.2–84.2) | 6.00 (3.1–8.7) | 99.00 (99.1–99.9) |

| LV diastolic dysfunction (moderate to severe) | |||||||||

| (n = 37) | (n= 88) | ||||||||

| Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | PPV (95% CI) | NPV (95% CI) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | PPV (95% CI) | NPV (95% CI) | ||

| Strategy 2 | ECG abnormal | 29.73 (15.0–44.5) | 86.68 (83.3–90.0) | 17.19 (7.9–26.4) | 92.99 (90.4–95.6) | 19.32 (11.1–27.6) | 90.76 (89.2–92.3) | 11.89 (6.6–17.2) | 94.58 (93.3–95.8) |

| Strategy 3 | NT-proBNP abnormal (>278 pg/mL) | 56.76 (40.8–72.7) | 83.42 (79.8–87.1) | 24.10 (15.1–33.1) | 95.40 (93.2–97.6) | 35.23 (25.2–45.2) | 90.18 (88.6–91.8) | 18.80 (12.8–24.7) | 95.60 (94.4–96.7) |

| Strategy 4 | ECG abnormal and NT-proBNP abnormal | 29.73 (15.0–44.5) | 96.98 (95.3–98.7) | 47.80 (27.4–68.2) | 93.70 (91.3–96.0) | 14.77 (7.4–22.2) | 98.24 (97.5–98.9) | 35.10 (19.8–50.5) | 94.70 (93.5–95.9) |

| Strategy 5 | ECG abnormal or NT-proBNP abnormal | 56.76 (40.8–72.7) | 73.12 (68.8–77.5) | 16.41 (10.0–22.8) | 94.79 (92.3–97.3) | 39.77 (29.5–50.0) | 82.70 (80.7–84.7) | 12.92 (8.9–16.9) | 95.51 (94.3–96.7) |

| Stage B heart failure | |||||||||

| (n = 337) | (n = 945) | ||||||||

| Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | PPV (95% CI) | NPV (95% CI) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | PPV (95% CI) | NPV (95% CI) | ||

| Strategy 2 | ECG abnormal | 16.32 (12.4–20.3) | 90.82 (85.1–96.5) | 85.94 (77.4–94.5) | 23.99 (19.6–28.3) | 11.96 (9.9–14.0) | 94.08 (92.0–96.1) | 79.02 (72.3–85.7) | 36.44 (33.8–39.0) |

| Strategy 3 | NT-proBNP abnormal (>278 pg/mL) | 22.55 (18.1–27.0) | 88.78 (82.5–95.0) | 87.36 (80.4–94.3) | 25.00 (20.5–29.5) | 13.86 (11.7–6.1) | 93.29 (91.1–95.5) | 79.39 (73.2–85.6) | 36.75 (34.1–39.4) |

| Strategy 4 | ECG abnormal and NT-proBNP abnormal | 6.82 (4.1–9.5) | 100.00 (100.0–100.0) | 100.00 (100.0–100.0) | 23.79 (19.7–27.9) | 3.92 (2.7–5.2) | 100.00 (100.0–100.0) | 100.00 (100.0–100.0) | 35.83 (33.3–38.3) |

| Strategy 5 | ECG abnormal or NT-proBNP abnormal | 32.05 (27.1–37.0) | 79.59 (71.6–87.6) | 84.38 (78.1–90.7) | 25.41(20.5–30.3) | 21.90 (19.3–24.5) | 87.38 (84.5–90.3) | 76.38 (71.3–81.4) | 37.51 (34.7–40.3) |

- a CI, confidence interval; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

Compared with strategy 1 (Doppler TE for all) that we considered as the reference, the other four strategies all showed a high specificity and negative predictive value (NPV) for identifying systolic ALVD, irrespective of the level of risk. All strategies also showed good specificity and NPV in detecting moderate to severe diastolic ALVD both in the high-risk group and in the whole study population. The specificity and NPV for identifying overall stage B HF were low for all strategies, in the high-risk group and in the whole population (Table 5).

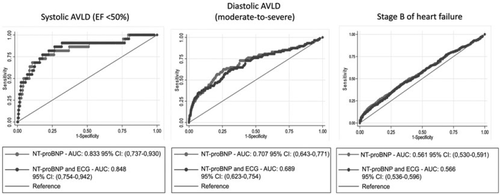

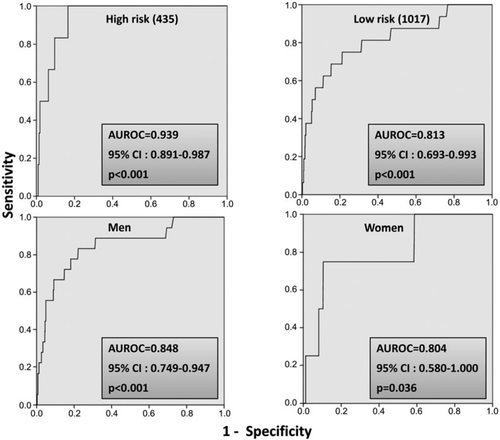

The ROC analyses to evaluate the accuracy of NT-proBNP alone and in combination with ECG to identify pre-clinical HF are reported in Figures 2 and 3, and in the Supplementary material, Figures S1 and S2. Figure 2 shows the accuracy of NT-proBNP in identifying systolic ALVD (EF <50%), moderate to severe diastolic ALVD, and stage B HF in the whole study population (1452 subjects). The AUROC was statistically significant in identifying systolic ALVD and diastolic AVLD but inadequate in identifying stage B HF (Figure 2, right panel). Adding ECG to NT-proBNP did not improve the accuracy of the discrimination in a multivariate model (Figure 2) and did not show statistically significant differences between the high-risk subgroups or the whole population in identifying systolic ALVD, diastolic ALVD, and stage B HF (all P > 0.05). The accuracy of NT-proBNP in identifying systolic AVLD did not differ between the high- and the low-risk groups and for gender (Figure 3). No statistically significant difference between groups in the accuracy of NT-proBNP was found in identifying diastolic AVLD or stage B HF (Supplementary material, Figures S1 and S2).

Cost-effectiveness of screening strategies

Costs of screening strategies and of each ALVD and stage B HF case identified in the whole population (1452 subjects) are shown in Table 6. Strategy 3 (all subjects to undergo NT-proBNP measurement; those with raised NT-proBNP then undergo TE) was the most cost-effective in identifying systolic ALVD (€1009.4 per case diagnosed). It was able to identify 14 of 22 cases (63.6%) of systolic ALVD (EF <50%), saving €3.076 per any case detected compared with strategy 1. This strategy showed less accuracy in detecting diastolic ALVD (only 13.9% including mild diastolic dysfunction), with many undiagnosed cases (86.1%). However, it identified 35.2% of subjects with moderate to severe diastolic AVLD and had the lowest cost for each case detected (€90). In contrast, Doppler TE was the most cost-effective strategy for identifying stage B HF (65.1% of cases identified, with the lowest cost per case diagnosed) (Table 6). The cost-effectiveness of the four strategies in the high-risk subgroup (435 subjects) is shown in Table 7. Strategy 3 identified all six cases of systolic ALVD at the cost of €725.00, €3763.00 less than strategy 1 per diagnosed case, and 21 out of 452 (56.8%) subjects with moderate to severe AVLD at a cost of €189.30, €4299.00 less than strategy 1. Even though this strategy showed the best cost-effectiveness with a significant cost savings with respect to all other screening strategies, it failed to identify 16 cases (43.2%) of moderate to severe AVLD and 261 cases (77.4%) of stage B HF. Doppler TE was able to identify stage B HF in the vast majority of the elderly at high risk (77.5%), and was more cost-effective than the other strategies (Table 7). Table 8 shows the results of a sensitivity analysis comparing cost-effectiveness of different strategies over a range of costs of the diagnostic test. We analysed the cost for each diagnosed case for the five screening strategies setting the cost of ECG at €25.65 and of NT-proBNP at €9.14 over three different scenarios. Strategy 3 was confirmed to be the most cost-effective also when taking into account the different range of costs of ECG and NT-proBNP.

| Screening strategies | Cost of screening | No. and % of cases diagnosed | No. and % of cases not diagnosed | Cost for each case diagnosed | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy 1 gold standard (echo) | ||||||

| ALVD systolic (EF <50%) | ||||||

| Strategy 1 | €89 878.80 | 22 | 1.5a | 1.430 | 98.5a | €4085.40 |

| Strategy 2 | €17 429.30 | 9 | 40.9b | 13 | 59.1b | €1936.60 |

| Strategy 3 | €14 137.90 | 14 | 63.6b | 8.00 | 36.4b | €1009.40 |

| Strategy 4 | €30 576.80 | 7 | 31.8b | 15.00 | 68.2b | €4368.10 |

| Strategy 5 | €31 133.90 | 16 | 72.7b | 6.00 | 27.3b | €1945.90 |

| ALVD diastolic (moderate to severe) | ||||||

| Strategy 1 | € 89 878.80 | 88 | 6.1a | 1.364 | 93.9a | €1021.40 |

| Strategy 2 | €17 924.50 | 17 | 19.3b | 71 | 80.7b | €1054.40 |

| Strategy 3 | €15 190.20 | 31 | 35.2b | 57 | 64.8b | €90.00 |

| Strategy 4 | €30 948.20 | 13 | 14.8b | 75 | 85.2b | €2380.60 |

| Strategy 5 | €32 310.00 | 35 | 39.8b | 53 | 60.2b | €923.10 |

| ALVD diastolic (all cases) | ||||||

| Strategy 1 | €89 878.80 | 604 | 41.6a | 848 | 58.4a | €148.80 |

| Strategy 2 | €21 638.50 | 77 | 12.7b | 527 | 87.3b | €281.00 |

| Strategy 3 | €18 470.90 | 84 | 13.9b | 520 | 86.1b | €219.90 |

| Strategy 4 | €31 505.30 | 22 | 3.6b | 582 | 96.4b | €1432.10 |

| Strategy 5 | €38 747.60 | 139 | 23.0b | 465 | 77.0b | €278.80 |

| ALVD systolic or diastolic | ||||||

| Strategy 1 | €89 878.80 | 609 | 41.9a | 843 | 58.1a | €147.60 |

| Strategy 2 | €21 824.20 | 80 | 13.1b | 529 | 86.9b | €272.80 |

| Strategy 3 | €18 656.60 | 87 | 14.3b | 522 | 85.7b | €214.40 |

| Strategy 4 | €31 629.10 | 24 | 3.9b | 585 | 96.1b | €1317.90 |

| Strategy 5 | €38 995.20 | 143 | 16.2b | 738 | 83.8b | €272.70 |

| Stage B heart failure | ||||||

| Strategy 1 | €89 878.80 | 945 | 65.1a | 507 | 34.9a | €95.10 |

| Strategy 2 | €23 866.90 | 113 | 12.1b | 823 | 87.9b | €211.20 |

| Strategy 3 | €21 380.20 | 131 | 13.9b | 814 | 86.1b | €163.20 |

| Strategy 4 | €32 433.80 | 37 | 3.9b | 908 | 96.1b | €876.60 |

| Strategy 5 | €42 956.80 | 207 | 21.9b | 738 | 78.1b | €207.50 |

- a ALVD, asymptomatic left ventruicular dysfunction.

- a Proportion of cases diagnosed or not diagnosed out of the whole population (n = 1452).

- b Proportion of cases diagnosed or not diagnosed through the different strategies out of the cases identified through strategy 1.

| Screening strategies | Cost of Screening | No. and % of cases diagnosed | No. and % of cases not diagnosed | Cost for each case diagnosed | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy 1 gold standard (echo) | ||||||

| ALVD systolic (EF <50%) | ||||||

| Strategy 1 | €26 927.00 | 6 | 1.4 | 429 | 98.6 | €4488.00 |

| Strategy 2 | €5302.30 | 4 | 66.7 | 2 | 33.3 | €1326.00 |

| Strategy 3 | €4347.30 | 6 | 100 | 0 | 0 | €725.00 |

| Strategy 4 | €9278.20 | 4 | 66.7 | 2 | 33.3 | €2320.00 |

| Strategy 5 | €9402.00 | 6 | 100 | 0 | 0 | €1567.00 |

| ALVD diastolic (moderate to severe) | ||||||

| Strategy 1 | €26 927.00 | 37 | 8.5 | 398 | 91.5 | €727.76 |

| Strategy 2 | €5735.60 | 11 | 29.7 | 26 | 70.3 | €521.42 |

| Strategy 3 | €5275.80 | 21 | 56.8 | 16 | 43.2 | €251.23 |

| Strategy 4 | €9711.50 | 11 | 29.7 | 26 | 70.3 | €882.86 |

| Strategy 5 | €10 330.50 | 21 | 56.8 | 16 | 43.2 | €491.93 |

| ALVD diastolic (all cases) | ||||||

| Strategy 1 | €26 927.00 | 202 | 46.4 | 233 | 53.6 | €133.30 |

| Strategy 2 | €7406.90 | 38 | 18.8 | 164 | 81.2 | €194.92 |

| Strategy 3 | €7070.90 | 50 | 24.8 | 152 | 75.2 | € 141.42 |

| Strategy 4 | €10 021.00 | 16 | 7.9 | 186 | 92.1 | €626.31 |

| Strategy 5 | €13 487.40 | 72 | 35.6 | 130 | 64.4 | €187.33 |

| ALVD systolic or diastolic | ||||||

| Strategy 1 | €26 927.00 | 203 | 46.7 | 232 | 53.3 | €132.65 |

| Strategy 2 | €7468.80 | 39 | 19.2 | 164 | 80.8 | €191.51 |

| Strategy 3 | €7132.80 | 51 | 25.1 | 152 | 74.9 | €139.86 |

| Strategy 4 | €10 082.90 | 17 | 8.4 | 186 | 91.6 | €593.11 |

| Strategy 5 | €13 549.30 | 73 | 36 | 130 | 64 | €185.61 |

| Stage B heart failure | ||||||

| Strategy 1 | €26 927.00 | 337 | 77.5 | 98 | 22.5 | €79.90 |

| Strategy 2 | €8459.20 | 55 | 16.3 | 282 | 83.7 | €153.80 |

| Strategy 3 | €8680.30 | 76 | 22.6 | 261 | 77.4 | €114.21 |

| Strategy 4 | €10 454.30 | 23 | 6.8 | 314 | 93.2 | €454.53 |

| Strategy 5 | €15 715.80 | 108 | 32 | 229 | 68 | €145.52 |

- a ALVD, asymptomatic left ventruicular dysfunction.

| Unit cost of each test (euro) | Cost per case of ALVD systolic (<50%) | Cost per case of ALVD siastolic (any) | Cost per case of stage B | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TE | ECG | NT-proBNP | Strategy 1 | Strategy 2 | Strategy 3 | Strategy 4 | Strategy 5 | Strategy 1 | Strategy 2 | Strategy 3 | Strategy 4 | Strategy 5 | Strategy 1 | Strategy 2 | Strategy 3 | Strategy 4 | Strategy 5 |

| General population | |||||||||||||||||

| 61.90 | 11.62 | 9.14 | 4085.4 | 1936.6 | 1009.8 | 4368.1 | 1945.9 | 148.8 | 281 | 219.9 | 1432.1 | 278.8 | 95.1 | 211.2 | 163.2 | 876.6 | 307.5 |

| 61.90 | 25.65 | 9.14 | 4085.4 | 4200.1 | 1009.8 | 7278.3 | 3219.1 | 148.8 | 545.6 | 219.9 | 2358.0 | 425.3 | 95.1 | 391.5 | 163.2 | 1365.3 | 305.9 |

| 61.90 | 11.62 | 15.74 | 4085.4 | 1936.6 | 1694.4 | 5737.1 | 2544.8 | 148.8 | 281.0 | 334.0 | 1867.7 | 347.7 | 95.1 | 211.2 | 236.4 | 1135.6 | 253.8 |

| 61.90 | 25.65 | 15.74 | 4085.4 | 4200.1 | 1694.4 | 8647.4 | 3818.0 | 148.8 | 545.6 | 334.0 | 2793.6 | 494.3 | 95.1 | 391.5 | 236.4 | 1686.2 | 352.2 |

| High-risk ropulation | |||||||||||||||||

| 61.90 | 11.62 | 9.14 | 4487.7 | 1325.6 | 724.6 | 2319.6 | 1567.0 | 133.3 | 194.9 | 141.4 | 626.6 | 186.8 | 79.9 | 153.8 | 114.2 | 454.5 | 145.5 |

| 61.90 | 25.65 | 9.14 | 4487.7 | 2851.3 | 724.6 | 3845.3 | 2584.2 | 133.3 | 355.5 | 141.4 | 1007.8 | 272.1 | 79.9 | 264.8 | 114.2 | 719.9 | 202.0 |

| 61.90 | 11.62 | 15.74 | 4487.7 | 1325.6 | 1203.1 | 3037.3 | 1983.6 | 133.3 | 194.9 | 198.8 | 805.8 | 227.2 | 79.9 | 153.8 | 152.0 | 579.4 | 172.1 |

| 61.90 | 25.65 | 15.74 | 4487.7 | 2851.3 | 1203.1 | 4563.1 | 3062.7 | 133.3 | 355.5 | 198.8 | 1187.2 | 312.0 | 79.9 | 264.8 | 152.0 | 844.7 | 228.6 |

- a ALVD, asymptomatic left ventricular dysfuction.

Discussion

This study shows that in an urban population of elderly people with high prevalence of stage B HF, NT-proBNP was the most accurate and cost-effective screening strategy to identify both asymptomatic systolic and moderate to severe diastolic LVD. The accuracy of NT-proBNP did not differ in the higher risk subgroup compared with the whole population or by gender. Adding ECG to the NT-proBNP assessment did not improve the detection of pre-clinical LVD in the whole population or in subgroups of different risk levels or gender. Doppler TE-based screening was the least cost-effective strategy for identifying ALVD. All screening strategies in fact were shown to be inadequate for identifying stage B HF.

Both the prevalence and the incidence of ALVD and stage B HF5,6,8,10,12,13,30 are higher in the elderly than in the general population, which has relevant prognostic implications14,15 and justifies, in the opinion of various authors, the need for screening most for systolic ALVD.16–22 Although current guidelines do not support the use of a therapy in subjects with diastolic dysfunction and/or HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF),3 evidence exists showing that treating conditions that are concomitant or causative of LV diastolic dysfunction (such as hypertensive LVH or concentric remodelling) can lead to improvement of prognosis and that a good adherence to treatments can slow the progression of such cardiac abnormalities and the development of overt HF.30 In this view, screening for all cardiac abnormalities (stage B HF) and not only for systolic ALVD can also be justified. HFpEF (i.e. diastolic dysfunction) is continuously increasing with the ageing of the population,10–12,31,32 raising serious prognostic32 as well as diagnostic concerns particularly in the elderly in whom it may be underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed.11,23,34 Diagnosis actually requires a comprehensive, often complex and time-consuming Doppler TE imaging of diastolic dysfunction.11,12,27,28 In the setting of screening, the accuracy of ECG is generally low and echocardiographic criteria to detect AVLD take time and are costly. Hence there is still uncertainty about which strategy is at present the most cost-effective to detect pre-clinical HF, as well as which marker of pre-clinical HF could be more useful among systolic or diastolic ALVD, or with structural abnormalities such as LVH or concentric remodelling, or any abnormality configuring stage B HF.

The Health ABC HF score showed that a multiparametric score was better than natriuretic peptides in identifying stage B HF24 that was shown to be associated with subclinical cardiac structural changes in the general population.35 However, these studies were carried out in ‘young’ people, 30–65 yearss old. In the Olmsted study, a strategy based on BNP or NT-proBNP screening to detect systolic LVD (EF <40%) in the general population21 yielded an increased burden of imaging to confirm cases. In the study by Galasko et al.,19 screening high-risk subjects was more cost-effective than screening low-risk subjects. TE screening was the least cost-effective strategy, whereas NT-proBNP and ECG screening were equally cost-effective. A combination of diagnostic tests such as 12-lead ECG and biomarker determination (BNP or NT-proBNP) was shown to be more cost-effective than imaging-based screening with TE.22

In the present study, NT-proBNP was moderately accurate in detecting systolic and moderate to severe diastolic ALVD. It still was shown to be the most cost-effective strategy, with significant savings compared with all other screening strategies. Thus, as in the study by Galasko et al.,19 in the present study a first-line Doppler TE screening was the least cost-effective strategy. Nevertheless, the strategy based on the assessment of NT-proBNP failed to identify about half (43.2%) of the moderate to severe AVLD cases in the high-risk subgroup and ∼65% of them in the whole population. Adding ECG to the NT-proBNP assessment, however, did not improve the detection of pre-clinical LVD.

In contrast to the study by Gupta et al.,24 the present study of a high-risk elderly population showed that NT-proBNP was inadequate to detect stage B HF. All screening strategies in fact were shown to be more inadequate in identifying stage B HF than Doppler TE, at least in this elderly population.

Notably, since the great majority of the patients from our cohort showed asymptomatic LV diastolic dysfunction or HFpEF,11 the careful evaluation of diastolic function carried out in this setting probably played a role in the early detection of LV impairment that then overwhelmed that of NT-proBNP.11,32,36 However, natriuretic peptides can actually be considered as first-line tools in the long-term management of subjects at risk of incident HF both for their cost-effectiveness and for the prognostic value they have shown in asymptomatic subjects. Future prospective studies will investigate their efficacy in reclassifying subjects from lower to higher risk strata to address preventive treatments.

Study limitations

In this study we have selected only the subset of subjects for whom all parameters were available. In order to consider the potential selection bias, we analysed the demographic and clinical characteristics of subjects included in the present analysis (n = 1452) and compared them with that of subjects excluded for technical reasons (unavailable measures for EF, diastolic dysfunction, LV mass, ECG, or NT-proBNP) (n = 421 people).

The two groups showed a similar prevalence of previous CHD (6.9% vs. 6.5%, P = 0.824), AH (58.2% vs. 56.2%, P = 0.503), VHD (3.6% vs. 2.3%, P = 0.308), T2DM (17.6% vs. 16.0%, P =0.411), peripheral artery disease (5.1% vs. 4.5%, P = 0.732), positive case history for use of cardiotoxins (0.2% vs. 0.3%, P = 0.894), and impaired renal function (eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 body surface area) (19% vs. 18%, P = 0.824). However, the subjects excluded from the study were older (42.3% vs. 32.3%, P < 0.004), were more often males (56.1% vs. 50.0%, P < 0.031), and showed a higher prevalence of AF (3.6% vs. 0.8%, P < 0.001). Considering these results regarding the general similarity between the two groups, we think that the selection bias might have had a minimal impact on the results.

Conclusions

In an urban elderly population, NT-proBNP is the most accurate screening strategy to identify systolic and moderate to severe diastolic LVD, whereas it was inadequate in detecting stage B HF. NT-proBNP-based screening strategies in subjects over 65 years of age offer an advantage in terms of cost-effectiveness.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Journal of Heart Failure online.

Funding

Takeda Italia Farmaceutici S.p.A, Rome, Italy; the funders had no role in the concept or design of the study, or in the data reporting.

Conflict of interest: none declared