Using Electrofishing Catch Rates to Estimate the Density of Largemouth Bass

Abstract

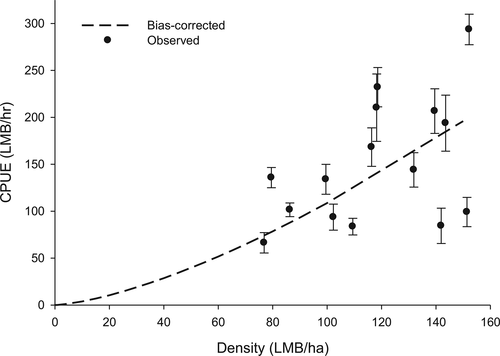

Catch rates are commonly used to indirectly index population density, e.g., nighttime electrofishing to survey Largemouth Bass Micropterus salmoides populations. However, the relationship between catch rate and population density must be known in order for catch rate to serve as an accurate index. We sought to determine if Largemouth Bass electrofishing catch rate was linearly or nonlinearly correlated to population density in high density populations using measurement-error models and Monte Carlo simulations. Previous studies of the relationship between Largemouth Bass electrofishing catch rate and density have occurred in low-density populations (<50/ha). We hypothesized that high-density Largemouth Bass populations may result in gear saturation during electrofishing sampling, i.e., too many fish for dipnetters to capture resulting in missed captures. This would therefore underrepresent the population's density. The nighttime electrofishing catch rate of 66–294 Largemouth Bass/h was linearly related to their population density (77–152/ha) over 15 experimental events. The linear relationship suggests electrofishing catch rate is an appropriate index of population density in similar high-density Largemouth Bass populations.

Received August 11, 2014; accepted December 3, 2014

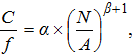

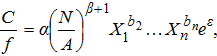

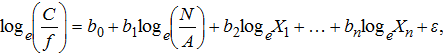

Standardized surveys are used to assess the status of fish populations; often with the assumption that catch rate (C/f) is linearly (proportionally) related to population density (N/A) because sampling is random and (or) gear saturation is minimal (Ricker 1975; Richards and Schnute 1986). However, gear saturation and nonrandom sampling effort may cause catchability to vary with population density, producing a nonlinear relationship between catch rate and density (Peterman and Steer 1981; Hansen et al. 2004; Schoenebeck and Hansen 2005) such that catch rate remains static as population density decreases, a relationship termed “hyperstability” (Peterman and Steer 1981; Hilborn and Walters 1992). In addition, catch rate could decrease at a faster rate than population density, i.e., “hyperdepletion,” because fish respond to the gear, such that highly vulnerable fish within a population are removed more quickly than less vulnerable fish (Hilborn and Walters 1992). Tests of nonlinearity between catch rate and population density are problematic because both catch rate and population density are measured with error, thereby rendering estimates of catchability potentially biased when using ordinary least-squares regression (OLS; Ricker 1975; Shardlow et al. 1985). Measurement errors in both C/f and N/A must be accounted for when estimating parameters to correctly estimate the shape of the relationship between catch rate and population density.

The relationship between electrofishing catch rate and population density of Largemouth Bass Micropterus salmoides remains poorly resolved, in part, because early catchability investigations assumed a linear relationship and did not test for the possibility of nonlinearity (Hall 1986; Coble 1992; McInerny and Degan 1993). More recent studies have accounted for the possibility of a nonlinear relationship between Largemouth Bass electrofishing catch rate and population density but have found inconsistent results and are from water bodies in the northern range of this species with low population densities. Largemouth Bass electrofishing catch rate was linearly related to population density in Wisconsin lakes (Schoenebeck and Hansen 2005), whereas this relationship was nonlinear in Minnesota lakes (McInerny and Cross 2000). These different outcomes represent a substantial sampling adjustment in how changes in Largemouth Bass abundance must be detected by fisheries managers; direct estimation through mark–recapture versus indirect estimation using catch rates. Although these previous studies estimated the relationship between Largemouth Bass electrofishing catch rate and population density in low-density Wisconsin lakes (mean, 17 bass/ha; one population exceeded 30 bass/ha; Schoenebeck and Hansen 2005) and Minnesota lakes (mean, 26 bass/ha; no densities exceeded 50 bass/ha; McInerny and Cross 2000), the relationship between catch rate and population density remains unknown for higher densities (>50 bass/ha).

Nighttime electrofishing is commonly used by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission (NGPC) to survey Largemouth Bass populations in Nebraska's lakes; which can have high densities (Lundgren et al. 2014). High population densities increase the probability of gear saturation and therefore hyperstability. This examination of catchability was conducted during the fall because of concerns surrounding higher catch rates (McInerny and Cross 2000; Schoenebeck and Hansen 2005) and uneven spatial distribution of Largemouth Bass during spring spawning (e.g., increased probability for gear saturation and unequal vulnerability). Fall sampling when fish were more evenly distributed along the shoreline offered the best opportunity for a linear relationship in these high-density lakes (Ho). Alternatively, higher population densities could increase the probability of gear saturation and therefore the probability of hyperstability (Ha). Our objective was to determine if Largemouth Bass electrofishing catch rate was linearly or nonlinearly related to population density during the fall.

METHODS

Eight study lakes were selected to represent Nebraska's Interstate-80 (I-80) lakes, including the range of Largemouth Bass densities commonly encountered (Table 1). Nebraska's I-80 lakes are borrow pits consisting of sandy substrates that were dredged or pumped during the 1960s construction of I-80 (McCarraher et al. 1974). The NGPC has established Largemouth Bass, Bluegill Lepomis macrochirus, and Channel Catfish Ictalurus punctatus as priority management species in these lakes, although low densities of other fish species are also present (Lundgren et al. 2014).

| Lake name | Surface area (ha) | Start date | Outings | CPUE (SE) | Marked (%) | Recaptures | Density (95% CI) | Temperature (°C; SD) | Conductivity (μS/cm, SE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bufflehead | 5.13 | 8/31/2010 | 5 | 168 (21) | 39.4 | 65 | 116 (92–148) | 21.8 (0.4) | 735 (4) |

| 9/12/2011 | 7 | 66 (11) | 45.8 | 50 | 77 (59–101) | 18.7 (0.9) | 767 (6) | ||

| Crystal | 3.01 | 9/2/2010 | 4 | 144 (18) | 37.3 | 47 | 132 (100–174) | 22.7 (0.6) | 1,217 (1) |

| 9/14/2011 | 6 | 194 (30) | 65.3 | 153 | 144 (123–168) | 18.3 (0.5) | 1,148 (116) | ||

| Fremont | 9.92 | 9/2/2010 | 6 | 294 (16) | 34.9 | 181 | 152 (132–176) | 21.1 (0.7) | 973 (4) |

| 9/14/2011 | 7 | 232 (21) | 33.0 | 113 | 119 (99–142) | 18.8 (0.7) | 892 (1) | ||

| Ft. Kearny #5 | 1.09 | 8/31/2010 | 5 | 188 (23) | 60.6 | 77 | 235 (188–292) | 23.5 (0.6) | 702 (5) |

| 9/12/2011 | 7 | 84 (19) | 70.4 | 74 | 142 (113–177) | 19.8 (0.9) | 735 (4) | ||

| Kea West | 2.98 | 8/31/2010 | 5 | 136 (11) | 62.3 | 77 | 80 (64–99) | 21.6 (0.5) | 1,128 (4) |

| 9/12/2011 | 7 | 94 (14) | 51.5 | 51 | 102 (78–134) | 19.0 (1.0) | 1,141 (2) | ||

| Pawnee | 12.20 | 9/1/2010 | 6 | 99 (16) | 17.4 | 49 | 151 (115–199) | 21.7 (0.8) | 410 (6) |

| 9/14/2011 | 8 | 210 (36) | 34.1 | 134 | 118 (100–140) | 17.6 (1.0) | 423 (4) | ||

| West Gothenburg | 4.72 | 9/1/2010 | 5 | 134 (16) | 43.4 | 78 | 100 (80–124) | 23.1 (0.8) | 376 (3) |

| 9/14/2011 | 7 | 207 (24) | 55.4 | 175 | 140 (120–162) | 19.5 (0.5) | 378 (9) | ||

| Windmill #2 | 1.17 | 8/31/2010 | 5 | 102 (7) | 76.5 | 72 | 86 (68–108) | 21.9 (0.5) | 1,030 (4) |

| 9/12/2011 | 7 | 84 (9) | 79.6 | 85 | 109 (89–135) | 19.4 (0.9) | 1,105 (19) |

Largemouth Bass catch rate (bass/h) and population density (bass/ha) were estimated in 16 experimental events each treated as independent and composed of multiple sampling occasions occurring within 30-d beginning August 31 to September 2 during 2010 and September 12 to 14 during 2011 (Table 1). Using a random starting point, Largemouth Bass were collected via nighttime electrofishing beginning approximately 30 min after sunset. For lakes <9 ha, the entire shoreline was sampled; for lakes >9 ha, sampling was stopped when at least 50 Largemouth Bass were collected. Smith-Root electrofishing boats (SR-16S and SR-18 models) were of standard design with two booms, and personnel consisted of two dipnetters and one operator. Power output followed NGPC sampling protocol by achieving a target output of 5–8 amps of pulsed DC at 100–200 V (Lundgren et al. 2014). Largemouth Bass were measured for total length (mm) and bass ≥150 mm were checked for a mark (fin clip), given a fin clip if not previously marked, and released (Carline et al. 1986; Lundgren et al. 2014). Population density (with 95% confidence intervals) was estimated by dividing each population estimate (derived using the Schnabel multiple mark–recapture method for all Largemouth Bass ≥150 mm) by lake surface area (Ricker 1975).

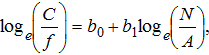

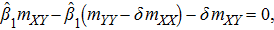

To evaluate the linearity of the relationship between electrofishing catch rate (y-axis) and population density (x-axis), the distribution of the bias-corrected estimates was used to empirically determine the median and 95% confidence interval for the slope and intercept. Bias-corrected slope estimates were tested for significant differences from one using the upper and lower 0.025 percentiles of the distribution of bias-corrected slopes (i.e., 95% confidence intervals).

is the bias-corrected slope, mYY is the estimated variance in Y, mXX is the estimated variance in X, mXY is the estimated covariance between X and Y, and δ is the Y/X measurement error ratio (MER) estimated iteratively (Fuller 1987; Quinn and Deriso 1999).

is the bias-corrected slope, mYY is the estimated variance in Y, mXX is the estimated variance in X, mXY is the estimated covariance between X and Y, and δ is the Y/X measurement error ratio (MER) estimated iteratively (Fuller 1987; Quinn and Deriso 1999).RESULTS

A total of 4,359 Largemouth Bass were sampled over the 16 experimental events and each lake was sampled a minimum of four and a maximum of eight times within each experimental event (Table 1). Largemouth Bass electrofishing catch rates in the study lakes averaged 152 bass/h (SE, 16; range 66–293); population densities averaged 125 bass/ha (SE, 10; range, 77–235). The percent of the Largemouth Bass population that was marked averaged 50.4% (SE, 4.4; range, 17.4–79.6%) over the 16 experimental events. The number of recaptured marks per experiment averaged 92.6 (SE, 11.2; range, 47–181). The 95% confidence intervals for Largemouth Bass density were on average within 19.3% of the density estimate (range, 13.5–24.4%). The Largemouth Bass density for Ft. Kearny #5 sampled during 2010 was estimated to be 235 bass/ha, or 83 bass/ha greater than the next highest density and more than two standard deviations from the mean. Therefore, it was removed and not included in further analysis.

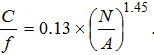

Mean (SE) electrofishing CPUE as a function of population density for Largemouth Bass (LMB) in Nebraska's I-80 lakes. The dashed line represents the bias-corrected line.

DISCUSSION

The relationship between Largemouth Bass catch rate and population density was linear, despite densities exceeding 77 bass/ha. These findings agree with results from low density lakes in Wisconsin (Schoenebeck and Hansen 2005), but not Minnesota (McInerny and Cross 2000). Sampling during the fall and the relatively small surface area of the study lakes may have allowed for thorough sampling of the Largemouth Bass populations in our study. Electrofishing catch rates are often lower during the fall than the spring because fish are concentrated during spring to spawn (McInerny and Cross 2000; Schoenebeck and Hansen 2005). Regarding gear saturation, spawning concentrations can be problematic because many fish can be simultaneously stunned, not allowing dipnetters to collect all of the stunned fish (Schoenebeck and Hansen 2005). In comparison, Largemouth Bass are not as concentrated in the fall and this even distribution of fish along the shoreline allowed dipnetters to successfully collect most stunned fish. In addition, the littoral zone of most study lakes was narrow (e.g., the width of the electrofishing booms) concentrating Largemouth Bass along the shoreline and allowing the boat to run parallel with the shoreline which permitted dipnetters to effectively collect stunned fish. Conversely, larger littoral zones in five Florida lakes necessitated driving the electrofishing boat in a zig-zig pattern out to 50 m from the shoreline to sample Largemouth Bass, possibly explaining differences in catchability among sampling occasions (Hangsleben et al. 2013). Gear saturation may increase if dipnetters are expected to collect all encountered fish; however, electrofishing catch rates of Largemouth Bass did not differ between intensive sampling for all species encountered versus rates from selective dipnetting of Largemouth Bass in 10 Texas reservoirs (Twedt et al. 1992). We postulate the combination of small littoral zones, which concentrated fish near the shoreline, and relatively even fish distribution along the shoreline minimized gear saturation and support the use of electrofishing catch rates to index population density in similar high-density lakes.

Linear relationships between electrofishing catch rate and population density have been documented for other species where gear saturation was minimal and sampling effort was random. For example, electrofishing catch rate was linearly related to population density for Common Carp Cyprinus carpio in Minnesota lakes (Bajer and Sorensen 2012), Muskellunge Esox masquinongy, and Northern Pike E. lucius in Wisconsin lakes (Schoenebeck and Hansen 2005) and Brook Trout Salvelinus fontinalis and Brown Trout Salmo trutta in Wisconsin streams (Bergman et al. 2011). Conversely, nonlinear relationships between eletrofishing catch rate and population density have been documented for other species where gear saturation can be problematic, in particular where behavioral concentrations of fish occur during the spring, such as Walleye Sander vitreus and Smallmouth Bass M. dolomieu (Schoenebeck and Hansen 2005). Given the range of available outcomes, managers should establish the relationship between electrofishing catch rate and population abundance for particular species, water types, and regions.

Largemouth Bass density was measured with greater error than electrofishing catch rate during our study, as indicated by a MER of less than 1.0 (0.77). However, catch rates are usually measured with greater error than population density (MER greater than 1.0, Schoenebeck and Hansen 2005). The low MER was unexpected, considering the high precision of the Largemouth Bass density estimates during our study (e.g., 50% of the estimated population was marked and 95% confidence intervals were within 20% of density estimate), but indicate consistent electrofishing catch rates among sampling occasions. Several factors probably contributed to consistent catch rates, including the duration of sampling, time of year, and small surface area of the study lakes. We limited sampling duration to 1 month because Largemouth Bass catch rates can vary over time as environmental variables such as water temperature and conductivity change (McInerny and Cross 2000; Schoenebeck and Hansen 2005). For example, variation in fall Largemouth Bass electrofishing catch rates were significantly explained by water conductivity in Minnesota lakes (McInerny and Cross 2000). Conversely, water temperature and conductivity were relatively static among sampling occasions during our study and therefore did not explain variation in Largemouth Bass catch rates similar to Wisconsin lakes (Schoenebeck and Hansen 2005). Sampling during the fall may also allow for consistent catch rates among sampling occasions because fish are in a relatively consistent feeding pattern, targeting optimum temperatures or prey (Bettross and Willis 1988). Although not quantified, angler harvest was probably low given the short duration of our experiment, the time of year, and low percentage of Largemouth Bass (1.79% were greater than the minimum length limit of 38.1 cm) vulnerable to angler harvest. Lastly, small lake surface areas may support consistent catch rates because we sampled the entire shoreline of most study lakes, which allowed a thorough sampling of the Largemouth Bass population.

MANAGEMENT IMPLICATIONS

Estimating population density from electrofishing catch rate is less costly and more efficient than mark–recapture methods, so more water bodies can be sampled at less cost (Hall 1986; Coble 1992; McInerny and Degan 1993). However, fishery managers must always be cognizant of the possibility that electrofishing catch rate could be nonlinearly related to population density (McInerny and Cross 2000). Therefore, we recommend that managers evaluate the linearity of relationships before using catch rates to estimate population density and thereby ensure that population-level changes are detected (Schoenebeck and Hansen 2005). In the sampled high-density lakes, Largemouth Bass electrofishing catch rate was linearly related to population density due to random and thorough sampling effort and minimal gear saturation in the fall. Therefore, we suggest electrofishing catch rates can be used in similar systems to indirectly estimate population density of Largemouth Bass in high-density lakes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank staff of the North Platte and Kearney Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, and the University of Nebraska Kearney for help in the field and laboratory, especially J. Kreitman, C. Huber, J. Lorensen, B. Newcomb, B. Eifert, B. Peterson, R. Alberts, N. Munter, J. Munter, C. Uphoff, D. Schumann, and M. Cavallaro. This project was funded by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission through Federal Aid in Sport Fish Restoration, Project F-190-R.