CHADS2 and modified CHA2DS2-VASc scores for the prediction of congestive heart failure in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation

Abstract

Background & purpose

We have conducted a retrospective observational study to analyze the correlation between the CHADS2 score, the modified CHA2DS2-VASc (mCHA2DS2-VASc) score, and the incidence of all-cause death and congestive heart failure (CHF).

Methods

The study cohort consisted of 292 consecutive patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) admitted to our hospital from 2012 to 2014. Electronic medical records were used to confirm medical history including prior heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, stroke, and coronary disease. A follow-up survey for all-cause deaths and incidence of CHF was carried out from the baseline data to May 2015. We analyzed the correlation between each score and the endpoints using the Kaplan-Meier method and the Cox proportional hazards model.

Result

During the follow up period (mean=1.6 years), 69 all-cause deaths and 58 CHF events occurred in the cohort. There was no significant association between these scores and all-cause death in our CHF cohort. The incidence of CHF significantly increased along with increased CHADS2 (p=0.018) or mCHA2DS2-VASc scores (p=0.044). The hazard ratio (HR) for CHF after adjustment for drug treatment was obtained from a Cox proportional hazards model. The HRs for the CHADS2 and mCHA2DS2-VASc scores were 1.38 (95% CI; 1.13–1.68) and 1.35 (95% CI; 1.24–1.59), respectively.

Conclusion

Calculation of the CHADS2 and mCHA2DS2-VASc scores in order to evaluate the risk of systemic thromboembolism was useful to predict the onset of CHF, but not all-cause death, in patients with NVAF.

1 Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) increases the risk of ischemic stroke, dementia, congestive heart failure (CHF), and all-cause death. Therefore, AF frequently decreases quality of life in a large number of elderly patients [1]. The CHADS2 [2] and modified CHA2DS2-VASc (mCHA2DS2-VASc) scores [3] for patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) have been proposed for the evaluation of the risk of systemic thrombosis including ischemic stroke.

AF rates have increased in tandem with the aging of the Japanese population, as in Western countries [4]. Indeed, the Japanese elderly population is growing particularly rapidly within the study area. Hence, evaluation of the risk and availability of the appropriate treatment for patients with AF in rural hospitals is particularly important.

Both the CHADS2 and mCHA2DS2-VASc scores are predictors of various categories of cardiovascular (CV) hospitalization among patients with NVAF or atrial flutter [5]. Moreover, it has been reported that the risk of death after stroke increases linearly with the CHADS2 score [6]. Perni et al. have recently demonstrated that the CHA2DS2-VASc score is an independent predictor of death and CHF events in patients undergoing cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) [7]. However, in rural areas of Japan, few studies on the correlation between established scoring systems and outcomes in patients with NVAF have been conducted.

Therefore, we conducted a retrospective observational study at a local base hospital in a coastal area of the Iwate prefecture in order to analyze the correlation between the CHADS2 score, the mCHA2DS2-VASc score, and the incidence of all-cause death and CHF in hospitalized patients with NVAF.

2 Materials and methods

A total of 1428 patients were hospitalized in our division of the Iwate Prefectural Ofunato Hospital between January 2012 and December 2014. Among this group, permanent (chronic) or paroxysmal AF was confirmed in 318 patients (22% of all inpatients) based on 12-lead and 24-hour monitoring electrocardiography. We excluded valvular AF (VAF: mitral valve stenosis=11, post-heart valve prosthesis=15), and analyzed the remaining patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF, n=292). The main reasons for admission were cardiovascular events such as CHF (n=120), arrhythmia (n=40), myocardial ischemia (n=43), and detailed cardiac examination (n=30). The remaining patients were hospitalized with pneumonia (n=27), dehydration (n=5), or other conditions (n=23). The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Iwate Prefectural Ofunato Hospital and conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Electronic medical records were used to evaluate background factors and medical history in order to establish baseline data as follows: age, gender, dates of admission, anticoagulant drug use (warfarin or NOAC; non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants), drugs for CHF, blood pressure, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) by echocardiography, prior history of heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, stroke, and coronary artery disease. Attending physicians administered anticoagulant therapy at their own discretion. The target PT-INR value for patients with AF who are prescribed warfarin is 2.0–3.0 (age ≥70 years old: 1.6–2.6).

The CHADS2 and mCHA2DS2-VASc scores were calculated based on data gathered at the index admission. In accordance with Gage's report [2], the CHADS2 score was calculated by assigning 1 point each for a prior history of CHF diagnosed by cardiologist or left ventricular dysfunction (LVEF <45%), hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg and/or medication), age 75 years or older, and diabetes mellitus (HbA1c ≥6.5% and/or medication); 2 points were assigned for a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack (max 6 points). In accordance with Okumura's report [3], the mCHA2DS2-VASc score was determined by assigning 1 point each for a prior history of CHF diagnosed by cardiologist or left ventricular dysfunction (LVEF <45%), hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg), age 65 years or older, age 75 years or older, and diabetes mellitus (HbA1c ≥6.5% and/or medication), coronary artery disease, and female gender; 2 points were assigned for a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack (max 9 points). The definition of “C” in CHADS2 and mCHA2DS2-VASc scores was a prior history of CHF as diagnosed during routine clinical practice, including history taking or echocardiography (left ventricular dysfunction defined as LVEF <45%). Patients were divided into three groups as follows: (1) the low score group (CHADS2 / mCHA2DS2-VASc score=0 points), (2) the intermediate score group (CHADS2 / mCHA2DS2-VASc score=1 points), and (3) the high score group (CHADS2 / mCHA2DS2-VASc score ≥2 points).

The follow-up survey for all-cause death and the incidence of complications was carried out from the baseline study (before discharge from the index admission) until May 2015. Authors investigated the date of all-cause death or rehospitalization with hemorrhagic disease, ischemic stroke, or CHF in patients who attended Ofunato Hospital after discharge. Confirmation of thromboembolism was based on clinical symptoms and CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings. The definition of the incidence of CHF in the present study was hospitalization due to “new onset or recurrent onset of CHF” as defined by the Framingham criteria [8]. CHF events were subdivided into two parts: heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF, LVEF <45%) and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF, LVEF ≥45%). Twenty-seven NVAF inpatients were transferred to a different hospital to receive treatment. Prognosis questionnaires regarding these patients were sent to the destination medical institution to evaluate their outcomes (response rate=93%). The follow-up rate of this study was 99%.

2.1 Statistical analysis

We conducted a retrospective observational study to analyze the correlation between the CHADS2 score, the CHA2DS2-VASc score, and the incidence of endpoints. Numerical values are expressed as means ± standard deviation. The Mann-Whitney U test for statistical analysis and the χ2 test for comparing ratios were used to compare background factors among the patient groups. The Kaplan-Meier method and univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were used to analyze outcomes among groups. The performance of each score in predicting the risk of CHF was analyzed with the C statistic and compared by differences in the area under the curve (AUC) according to the receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve.

The above analysis was performed using the software package SPSS 20.0 for Windows, with the level of significance set at p <0.05.

3 Results

Table 1 shows the clinical characteristics of the study subjects. The mean age at admission was 77.6 years. The proportion of males was significantly higher than that of females. Eighty-seven patients had not received anticoagulant drugs (30% of patients with NVAF), while 171 had received warfarin (59% of patients with NVAF) and 34 had received NOAC (11% of patients with NVAF) at discharge.

| Total (n) | 292 |

| Age (years) | 77.6±10.8 |

| Gender (male / female) | 166/126 |

| Without anticoagulant drug | 87 (30%) |

| Warfarin | 171 (59%) |

| NOAC | 34 (11%) |

| Loop diuretic | 177 (61%) |

| ACE inhibitors | 64 (22%) |

| ARB | 92 (32%) |

| Beta-blockers | 149 (51%) |

| Potassium-sparing diuretic | 57 (20%) |

| Digitalis | 56 (19%) |

| PD3 inhibitors | 4 (1.4%) |

| Average of LVEF (%) | 52.5±15.6 |

| Average CHADS2 score | 2.7±1.3 |

| Average mCHA2DS2-VASc score | 3.6±1.6 |

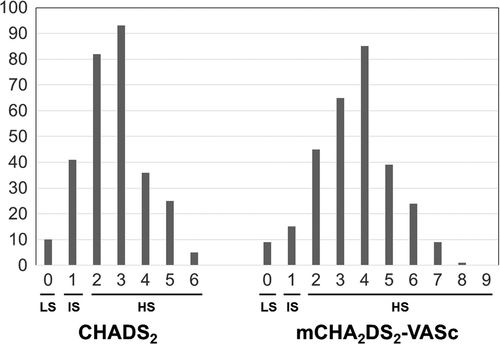

Mean CHADS2 and mCHA2DS2-VASc scores among the 292 patients with NVAF were 2.7 and 3.6 points, respectively. Fig. 1 shows the frequency distribution of each score in the patients with NVAF. None of the patients exhibited a mCHA2DS2-VASc score of 9 points.

Frequency distribution of each score in patients with NVAF. LS: Low score group (CHADS2 / mCHA2DS2-VASc score=0 point), IS: Intermediate score group (CHADS2 / mCHA2DS2-VASc score=1 point), HS: High score group (CHADS2 / mCHA2DS2-VASc score ≥2 points).

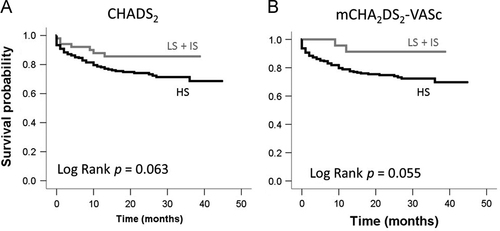

Table 2 shows the number of incidences of all-cause death, hemorrhage, embolism, and CHF. During the mean follow-up period of 1.6 years, 18 cases experienced thromboembolic events (ischemic stroke, n=16; other thromboembolisms, n=2). There was a significant association between thromboembolic events and the established scores in patients with NVAF (CHADS2; log rank p=0.046: mCHA2DS2-VASc; log rank p=0.043). There were 69 cases of all-cause death (23.6% in all patients with NVAF, annual mortality rate=12.3%), with approximately half (11.6%) of these deaths due to cardiovascular etiology (myocardial infarction, stroke, sudden cardiac death, or CHF). The probability of survival was not significantly associated with either score (Fig. 2).

| All-cause death | 69 (23.6%) |

| (Cardiovascular death) | 34 (11.6%) |

| Incidence of hemorrhage | 25 (8.6%) |

| (Gastrointestinal / Intracranial / Others) | 15/2/7 |

| Incidence of embolism | 18 (6.2%) |

| (Cerebral / Others) | 16/2 |

| Incidence of congestive heart failure | 58 (19.9%) |

| (HFrEF / HFpEF) | 23 (39.7%)/35 (60.3%) |

Survival probability rate in patients with NVAF. LS: Low score group (CHADS2 / mCHA2DS2-VASc score=0 point), IS: Intermediate score group (CHADS2 / mCHA2DS2-VASc score=1 point), HS: High score group (CHADS2 / mCHA2DS2-VASc score ≥2 points).

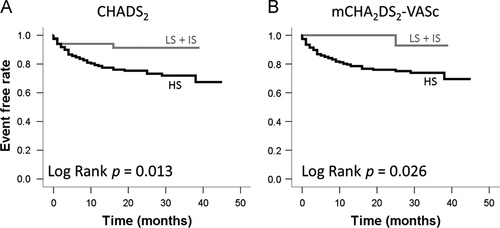

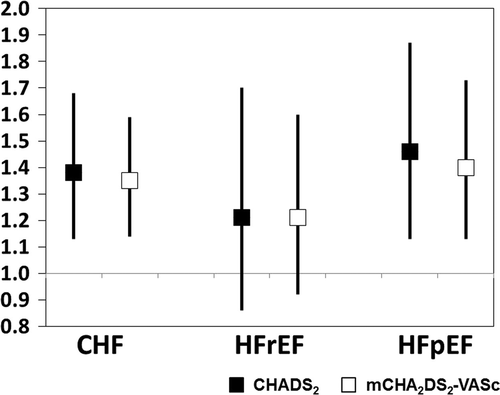

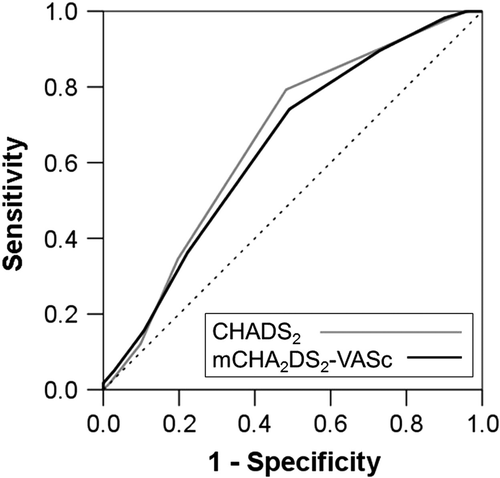

Twenty-percent of the patients with NVAF (n=58) developed CHF. The annual incidence of CHF in this NVAF population was 11.6%, and the rate increased according to the score group classification (CHADS2 score, LS=0%; IS=4.9%; HS=10.5%: mCHA2DS2-VASc score, LS=0%; IS=2.5%; HS=13.1%). The incidence of CHF increased significantly along with both increased CHADS2 scores (p=0.018) and mCHA2DS2-VASc scores (p=0.044). Event-free rates for CHF in the high CHADS2 score or high mCHA2DS2-VASc score groups were significantly reduced (CHADS2: log rank p=0.013; Fig. 3A, mCHA2DS2-VASc score: log rank p=0.026; Fig. 3B). Next, we analyzed the risk of CHF adjusted by the therapeutic agent used for treatment (renin-angiotensin system inhibitor and beta-blocker) using a Cox proportional hazards model (Fig. 4). In CHF, the hazard ratios (HRs) for the CHADS2 and mCHA2DS2-VASc scores were 1.38 (95% CI; 1.13–1.68) and 1.35 (95% CI; 1.24–1.59), respectively (Fig. 4 left). In particular, in HFpEF, the HRs for the CHADS2 and mCHA2DS2-VASc scores were significantly increased: 1.46 (95% CI; 1.13–1.87) and 1.40 (95% CI; 1.13–1.73), respectively (Fig. 4 right). On the other hand, the HR for HFrEF did not differ significantly for either scoring system (Fig. 4 middle). The AUC (Fig. 5) for the CHADS2 score was 0.66 (95% CI; 0.59–0.73). Similarly, the AUC for the mCHA2DS2-VASc score was 0.64 (95% CI; 0.59–0.72).

Event-free rate of CHF in patients with NVAF. LS: Low score group (CHADS2 / mCHA2DS2-VASc score=0 point), IS: Intermediate score group (CHADS2 / mCHA2DS2-VASc score=1 point), HS: High score group (CHADS2 / mCHA2DS2-VASc score ≥2 points).

Hazard ratio and 95% confidence interval for CHF. In CHF, HR for one point of CHADS2 or mCHA2DS2-VASc score adjusted by therapeutic agent (renin-angiotensin system inhibitor and beta-blocker). HFrEF: LVEF <45%; HFpEF: LVEF ≥45%.

Comparison of ROC curves for the prediction of heart failure between the CHADS2 and mCHA2DS2-VASc scores in patients with NVAF. AUC: CHADS2 score=0.66 (95% CI; 0.59–0.73), mCHA2DS2-VASc score=0.64 (95% CI; 0.59–0.72). The cutoff values according to ROC curves for CHADS2 score and mCHA2DS2-VASc score were > 3 points (sensitivity=0.793, specificity=0.593) and > 4 points (sensitivity=0.741, specificity=0.508).

In addition, we used a univariate Cox analysis to investigate the relationship between the clinical components of each scoring system and the incidence of CHF (Table 3). In both models, a history of CHF, age over 75 years, and diabetes mellitus were significant risk factors for the incidence of CHF. The hazard ratio for a history of CHF was especially high (HR=8.59; 95% CI 3.43–21.52).

| CHADS2 | EXP (B) | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHF history or LVEF <45% | 8.59 | 3.43–21.52 | <0.001 |

| HTa | 1.50 | 0.76–2.96 | 0.245 |

| Age ≥75 yrsb | 2.25 | 1.21–4.17 | 0.010 |

| DMc | 1.79 | 1.02–3.11 | 0.041 |

| Stroke history | 0.79 | 0.49–1.73 | 0.789 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc | EXP (B) | 95% CI | P value |

| CHF history or LVEF <45% | 8.59 | 3.47–1.96 | <0.001 |

| sBP ≥140d | 0.91 | 0.47–1.96 | 0.913 |

| Age 65–74 yrse | 1.42 | 0.47–4.34 | 0.538 |

| Age ≥75 yrse | 2.75 | 1.09–6.93 | 0.032 |

| DMc | 1.79 | 1.02–3.11 | 0.041 |

| Stroke history | 0.79 | 0.49–1.73 | 0.789 |

| CAD historyf | 1.20 | 0.67–2.13 | 0.536 |

| Gender (female) | 1.06 | 0.63–1.78 | 0.819 |

- a Prior history of hypertension.

- b Vs. age <75 years.

- c Prior history of diabetes mellitus.

- d Mean systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg.

- e Vs. age <65 years.

- f Prior history of coronary artery disease.

4 Discussion

The present study has clearly shown that the risk of CHF increases significantly along with increased CHADS2 or CHA2DS2-VASc scores among hospitalized patients with NVAF in the real-world setting of our general hospital located in a rural area.

The annual mortality of patients with NVAF in this cohort was 12.3%, which is clearly higher than that reported in the urban center of Tokyo (mean age=66.4 years, annual mortality=1.09%) [9]. This may be because participants in the present study were inpatients in a region with a large aging population, and these individuals were included in the number of discharges due to death.

In the present study, however, all-cause death was not significantly associated with CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores using the Kaplan-Meier method (Fig. 2). One report from Korea has demonstrated that high CHADS2 scores were associated with an increased risk of all-cause death [10]. In addition, CHF complicated by AF has a high mortality rate and a poor prognosis [11]-[13]. The discrepancies between our study and these previous reports were likely due to the relatively low percentage of cardiovascular deaths in our elderly cohort. In fact, half of the deaths in this study were not due to a cardiac cause, but to other conditions such as malignancy, infectious disease, and senility.

Risk prediction for the incidence of CHF in patients with AF is especially important since AF is highly associated with CHF in 40% to 60% of Japanese patients [14], [15]. Suzuki et al. proposed the use of the H2ARDD score (heart disease=2 points, anemia=1 point, renal dysfunction=1 point, diabetes=1 point, and diuretic use=1 point; range 0–6 points) for assessing the risk of CHF in patients with AF [16]. Although the H2ARDD scoring system has very good predictive value (AUC for CHF events=0.840), use of this score is not yet widespread in clinical practice. The present study focused on whether the CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores are related to cumulative CHF event-free rates in NVAF inpatients. Accordingly, we investigated the relationship between the incidence of CHF and these scores and found that both the CHADS2 and mCHA2DS2-VASc scores were useful for predicting the risk of CHF onset as shown in 3, 4.

In the present study, the significant risk factors for the incidence of CHF in patients with NVAF were history of CHF, age 75 years or older, and diabetes mellitus among the components of both scores. The HR for patients with a history of CHF in this univariate analysis was more than eight times greater than that for patients with no history of CHF (Table 2). This suggests that a history of CHF is a strong predictor of the recurrence of CHF in patients with AF. In fact, the JCARE-CARD prospective study of a broad sample of patients with CHF in Japan showed that the readmission rates for patients with CHF were high (27% within six months and 35% within one year) [17].

The merger rate of AF is higher in HFpEF than in HFrEF [18]-[20]. Likewise, in the present study, the rate of complicating HFpEF in patients with NVAF was higher than that of HFrEF. Generally, patients with HFpEF have a decreased risk of death compared to patients with HFrEF [18]. However, the risk of death in patients with HFpEF complicated with AF is higher than that in patients with HFrEF [21], [22]. In this study, the HRs for the CHADS2 or mCHA2DS2-VASc scores in HFpEF were significantly higher, whereas no significant differences were shown in HFrEF. The reasons for the difference appear to be as follows: (1) the statistical power of HFrEF was inadequate because the overall number of events was lower than that for HFpEF, and (2) the differing pathophysiologies of HFpEF and HFrEF. Zakeri et al. reported that exercise capacity and maximal oxygen consumption in patients with HFpEF and AF was significantly reduced with respect to patients with HFpEF and sinus rhythm [23]. In addition to left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, atrial contraction does not occur during left ventricular diastole in patients with AF.

Hypertension was not a significant predictor of CHF in patients with AF in the present study. It has been previously reported that hypertension is a risk factor for CHF [24] and that many patients with CHF have the complication of left ventricular hypertrophy due to hypertension [17],[25],[26]. We posit that this unexpected finding may have been due to the irregular pulse pressure inherent in AF that can reduce the accuracy of blood pressure measurement. Furthermore, severe left ventricular dysfunction associated with AF may reduce blood pressure. These factors may compromise the significance of the association between hypertension and the incidence of CHF.

In this cohort, diabetes mellitus was associated with incidence of CHF. Although it is not known whether diabetes mellitus in patients with AF is a strong risk factor for CHF, Kishimoto et al. have reported increased admission rates for CHF in patients with poor glycemic control during a 5-year follow-up [27]. This finding may be consistent with the results of the present study.

No relationship was found between a prior history of coronary artery disease and the incidence of CHF (Table 3). Several previous studies have demonstrated that coronary artery disease is the most frequent underlying cause of CHF [17],[25],[26], which appears to be inconsistent with our results. However, since the mean age of the patients in this cohort was very high, it is possible that insufficient coronary scrutiny was performed.

A few previous studies have reported differences in the impact of gender on the incidence of CHF in patients with AF. In the present study, gender had no significant effect on the prediction of CHF onset (Table 3). Although the male to female ratio of patients with CHF in selected teaching hospitals in Japan was reportedly 2:1 [26], a previous epidemiological study in our prefecture has shown no significant difference in the prevalence of CHF between males and females [11]. Although the association between gender and the incidence of CHF in patients with AF remains unclear, we speculate that there may be no difference between genders in terms of CHF morbidity in patients with AF.

4.1 Study limitations

Since the participants in this cohort were inpatients in a region with an advanced aging population, they often had serious comorbidities such as infections and malignancies. Hence, it is uncertain whether the results of our analysis would apply to outpatients in urban areas. In addition, since the present study used a retrospective cohort design, the existence of various types of bias is possible. Furthermore, the present study may have underestimated the number of CHF events, as patients treated in outpatient clinics were not included. In order to achieve a more accurate evaluation, a future prospective cohort study will be necessary.

5 Conclusions

Among real-world hospitalized patients with NVAF in a rural area, calculation of the CHADS2 and mCHA2DS2-VASc scores in the evaluation of the risk of thromboembolism was useful for the prediction of CHF, but not all-cause death. We propose that not only the potential for stroke but also the onset of CHF should be considered in patients with NVAF with higher CHADS2 or mCHA2DS2-VASc scores.

Funding

This research did not receive grants from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Makoto Chiba, Dr. Sanae Ohizumi, Dr. Makoto Inomata, Dr. Tsukasa Oikawa, Dr. Ichiro Yamazaki and Ms. Junko Iwabuchi for their outstanding contribution to the registration of AF patients.