Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cardiac failure: meta-analyses of observational studies and randomised controlled trials

Abstract

Aims:

To determine the risks of cardiac failure with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and the specific risks with Cox-2 specific NSAIDs (COXIBs).

Methods:

We performed meta-analyses examining the risks of developing cardiac failure in observational studies and in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) involving patients with arthritis and non-rheumatic disorders. Electronic databases and published bibliographies were systematically searched (1997–2008).

Results:

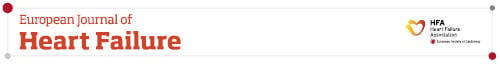

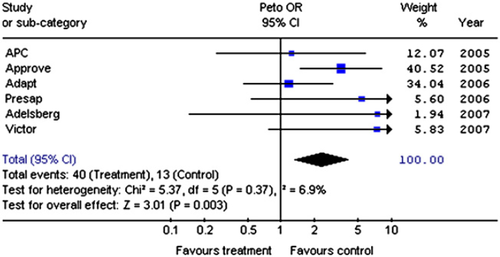

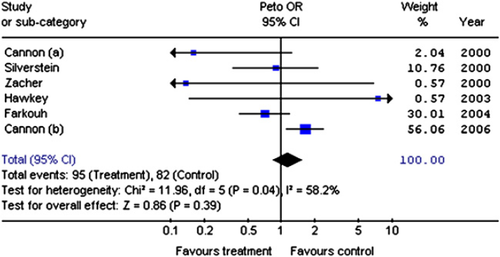

Five case—control studies (4657 patients, 45,862 controls) showed a non-significant association between NSAIDs and cardiac failure in a random effect model (odds ratio (OR) 1.36; 95% CI 0.99–1.85). Two cohort studies (27,418 patient years, 55,367 control years) showed a significant risk of cardiac failure with NSAIDs (relative risk 1.97; 95% CI 1.73–2.25). Six placebo-controlled trials (naproxen, rofecoxib and celecoxib) in non-rheumatic diseases (15,750 patients) showed more cardiac failure with NSAIDs (Peto OR 2.31; 95% CI 1.34, 4.00). Six RCTs comparing conventional NSAIDs and COXIBs in arthritis (62,653 patients) showed no difference in cardiac failure risk (Peto OR 1.14; 95% CI 0.85–1.53).

Conclusion:

Observational studies and RCTs all show that NSAIDs increase the risk of cardiac failure. Overall risks are relatively small and are similar with conventional NSAIDs and COXIBs. Pre-existing cardiac failure increases risk.

1. Introduction

There are concerns about cardiovascular toxicities with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and particularly with Cox-2 specific drugs (COXIBs). Systematic reviews 1 2 3 have shown that some NSAIDs increase myocardial infarctions. Another potential cardiovascular toxicity is cardiac failure, attributed to their effects on blood pressure and fluid retention 4. The extent to which NSAIDs increases the risk of cardiac failure, and the possibility of a specific increased risk with COXIBs, has not been examined in detail. We assessed these risks in meta-analyses examining the occurrence of cardiac failure with NSAIDs and COXIBs in observational studies and randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in arthritis and non-rheumatic diseases in which NSAIDs may have therapeutic roles.

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategies

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CINAHL (January 1997-March 2008) to find primary references and reviews together with published bibliographies and the Cochrane library. We used the following terms: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, Cox-2 inhibitors, cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors, rofecoxib, celecoxib, lumiracoxib, valdecoxib, etoricoxib, ibuprofen, diclofenac and naproxen; cardiac failure, congestive cardiac failure and heart failure; colonic adenoma, colonic polyps and colonic neoplasm; Alzheimer's disease, Alzheimer's and Alzheimer's dementia; prostate cancer, carcinoma of the prostate, and prostatic neoplasm; osteoarthritis (OA), rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and arthritis; case-control study, cohort study, observational study and randomised controlled trial. We considered only studies published in English (though no study was excluded because it was not written in English). We excluded studies with insufficient information to assess the presence or frequency of cardiac failure.

2.2. Types of study

We identified three categories of peer-reviewed papers:

- Case-control and cohort studies examining cardiac failure with NSAIDs.

- RCTs of NSAIDs in patients with colonic adenomas, Alzheimer's disease or a raised prostate specific antigen (PSA).

- RCTs comparing COXIBs with traditional NSAIDs or placebo in arthritis.

Our pre-existing knowledge of the literature 3 indicated that there are no trials directly comparing COXIBs with traditional NSAIDs in non-rheumatic disorders.

2.3. Data extraction

PAS and DLS independently assessed studies for eligibility and extracted data on year of publication, population source, design, size, settings, funding and study period. When there were differences between observers they reviewed the papers together to reach joint conclusions.

2.4. Statistics

Results were analysed using Review Manager 4.2.8 (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, United Kingdom). We evaluated the relative risk (RR) of cardiac failure in RCTs and cohort studies, and the odds ratios (OR) in case-control studies. The random effects model based on DerSimonian and Laird's method was used to estimate the pooled effect sizes in the observational studies 5. This gives more equal weighting to studies of different precision in comparison to a simple inverse variance weighted approach, so accommodating between study heterogeneity 6. The observational studies had differing selection criteria and patient risk profiles, and the true effect of NSAIDs on the occurrence of heart failure is therefore likely to vary between studies, making this model more appropriate. In the RCTs in arthritis and non-rheumatic diseases, where there were few events, we used the Peto odds ratio 7.

For all meta-analyses we performed Cochran's χ2 test to assess between study heterogeneity and quantified the I2 statistic 8 9 10. We considered a P value less than 0.05 as significant.

2.5. Quality

The quality of RCTs was assessed with the Jadad scoring instrument 11 (Table 1).

| Study (year) | Source | Age | Design/treatments | Cases/controls | Country | Funding source | Study period | Qualitya |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case-control studies with unexposed controls | ||||||||

| Page 12 | Attending hospitals | - | Case-control | 365/658 | Australia | NHMRC | 1993-95 | - |

| Pfizer | ||||||||

| García Rodríguez and Hernández-Díaz 13 | GP database | 40-84 | Case-control | 857/5000 | UK | AstraZeneca | 1996 | - |

| Bernatsky 14 | Healthcare databases | ≥18 | Case-control | 520/5200 | Canada | Aventis | 1998-2001 | - |

| Huerta et al. 15 | GP database | 60-84 | Case-control | 1396/5000 | UK | Pfizer | 1997-2000 | - |

| Hudson et al. 16 | Healthcare databases | ≥66 | Case-control | 8512/34,048 | Canada | CIHR | 1998-2003 | - |

| Cohort studies with unexposed controls | ||||||||

| Heerdink et al. 18 | Healthcare database | >55 | Retrospective cohort | 125/100 | The Netherlands | RDAAP | 1986-92 | - |

| Mamdani et al. 17 | Healthcare database | ≥66 | Retrospective cohort | 45,097/100,000 | Canada | CIHR | 2000-1 | - |

| Cohort studies comparing conventional NSAIDs with COXIBs | ||||||||

| Zhao et al. 19 | Healthcare database | - | Retrospective cohort | 55,396 | USA | - | 1999-2000 | - |

| Hudson et al. 20 | Healthcare databases | ≥66 | Retrospective cohort | 2256 | Canada | CIHR | 2000-2 | - |

| RCTs in patients with colonic adenomas, Alzheimer's disease, or raised PSA | ||||||||

| Solomon et al. (APC trial) 23 | Previous colorectal adenomas | 32-88 | Celecoxib/placebo | 1356/679 | USA | National Cancer Institute/Pfizer | 1999-2002 | |

| Canada | ||||||||

| UK | ||||||||

| Australia | ||||||||

| Bresalier (approve trial) et al. 22 | Previous colorectal adenomas | ≥40 | Rofecoxib/placebo | 1287/1299 | Multinat | Merck | 2000-01 | 5 |

| Arber et al. (Presap trial) 24 | Previous colorectal adenomas | ≥30 | Celecoxib/placebo | 933/628 | Multinat | Pfizer | 2001-5 | 4 |

| ADAPT Trialists 21 | Family history Alzheimer's disease | ≥70 | Celecoxib/naproxen/placebo | 726/719/1083 | USA | NIA | 2001-5 | 5 |

| Pfizer | ||||||||

| Bayer | ||||||||

| Kerr et al. (Victor trial) 25 | Previous colorectal carcinoma | ≥18 | Celecoxib/placebo | 1167/1160 | UK | Merck | 2002-4 | 4 |

| Adelsberg et al. 26 | Raised PSA but no evidence of prostate cancer | 50-75 | Rofecoxib/placebo | 2369/2372 | Multinat | Merck | 2003-4 | 5 |

| RCTs in patients with arthritis | ||||||||

| Cannon et al. 27 | Osteoarthritis | ≥40 | Rofecoxib/diclofenac | 516/268 | USA | Merck | 1996-97 | 4 |

| Silverstein et al. 28 | Osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis | ≥18 | Celecoxib/Ibuprofen/diclofenac | 3987/1985/1996 | USA | Pharmacia | 1998-2000 | 5 |

| Canada | ||||||||

| Hawkey et al. 29 | Rheumatoid arthritis | 21-85 | Rofecoxib/naproxen/placebo | 219/220/221 | Multinat | Merck | Not stated | 4 |

| Zacher et al. 30 | Osteoarthritis | ≥40 | Etoricoxib/diclofenac | 256/260 | Multinat | Merck | Not stated | 4 |

| Farkouh et al. 31 | Osteoarthritis | ≥50 | Lumiracoxib/ibuprofen | 9156/4415/4754 | Multinat | Novartis | Not stated | 5 |

| Cannon et al. [32] | Osteoarthritis or Rheumatoid arthritis | ≥50 | Etoricoxib/diclofenac | 17,412/17,289 | Multinat | Merck | 2002-6 | 5 |

- a Abbreviations: CCF, congestive cardiac failure; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; NHMRC, National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia; DMARDs, disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs; CIHR, Canadian Institutes of Health Research; NIA, National Institute on Aging; RDAAP, Royal Dutch Association for the Advancement of Pharmacy; PSA, prostate specific antigen.

- a Study quality was judged out of 5 for RCTs using Jadad scores.

3. Results

3.1. Cardiac failure in observational studies

Nine of 159 potentially relevant studies met our inclusion criteria. These comprised five 12 13 14 15 16 case-control studies and two 17,18 cohort studies comparing patients taking NSAIDs with unexposed controls, and two cohort studies comparing patients taking conventional NSAIDs with COXIBs without unexposed controls 19,20 (Table 1). The three types of study were analysed separately.

The case-control studies enrolled 4657 patients taking NSAIDs and 45,862 controls. NSAID use and cardiac failure was related in a random effects model (OR 1.36; 95% CI 0.99, 1.85) (Fig. 1 A). There was evidence of significant statistical heterogeneity between studies (χ2 = 43.95; df = 4; P < 0.001; I2 = 90.9%). However this was predominantly due to one study of cardiac failure with a considerably different study population 14. This study, by Bernatsky et al., which only considered patients with rheumatoid arthritis and excluded patients with pre-existing cardiac failure, showed no evidence of an association between NSAID use and cardiac failure. None of the other four studies, which all showed significant positive associations between NSAIDs and cardiac failure, excluded patients with pre-existing cardiac failure.

Comparison of conventional NSAIDs and individual COXIBs in the case-control studies (Table 2) showed significant associations with rofecoxib (OR 1.49; 95% CI 1.10, 2.02) but not celecoxib. There was no significant association with conventional NSAIDs (OR 1.35; 95% CI 0.94, 1.93). There was insufficient data to evaluate individual conventional NSAIDs or other COXIBs. There was significant statistical heterogeneity with conventional NSAIDs (Chi Squared = 38.27; df = 4; P < 0.001; I2 = 89.5%), again predominantly accounted the study by Bernatsky et al. with significantly different methodology 14, and celecoxib (Chi Squared = 6.74; df = 1; P = 0.009; I2 = 85.2%), but not rofecoxib (Chi Squared = 1.81; df = 1; P = 0.18; I2 = 44.7%).

| Case-control | Studies | Participants | Random effects OR (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| All NSAIDs | 5 | 50,519 | 1.36 (0.99, 1.85) |

| Conventional NSAIDs | 5 | 48,755 | 1.35 (0.94, 1.93) |

| Celecoxib | 2 | 41,400 | 0.85 (0.48, 1.50) |

| Rofecoxib | 2 | 41,023 | 1.49 (1.10, 2.02) |

| Cohort | Studies | Patient years | Episodes of cardiac failure | Relative risk (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All NSAIDs | 2 | 82,785 | 879 | 1.97 (1.73, 2.25) |

- a OR = odds ratio.

The two cohort studies comparing patients taking NSAIDs with unexposed controls 17,18 involved 27,418 years follow-up for patients receiving NSAIDs and 55,367 years follow-up for controls. They showed a significant risk (Fig. 1B) of developing cardiac failure whilst receiving NSAIDs (RR 1.97; 95% CI 1.73, 2.25). There was no evidence of statistical heterogeneity (χ2 = 0.95, df = 1, P = 0.33; I2 = 0%). The crude rate of cardiac failure was 16/1000 patient years with NSAIDs and 8/1000 patient years with placebo.

The two cohort studies comparing COXIBs with conventional NSAIDs without untreated controls 19,20 involved 18,591 years of follow-up with 1428 episodes of cardiac failure. Neither rofecoxib (RR 1.19; 95% CI 0.75, 1.90) nor celecoxib (RR 0.98; 95% CI 0.67, 1.46) use significantly increased the risk of cardiac failure compared to other NSAIDs. There was significant statistical heterogeneity between the studies (χ2 = 7.15, df = 1, P = 0.008, I2 = 86% with celecoxib and χ2 = 10.09, df = 1, P = 0.001, I2 = 90% with rofecoxib). However the studies had important differences in methodology with one study including only patients with a recent diagnosis of cardiac failure 20 and the other excluding such patients 19.

3.2. Cardiac failure in RCTs in non-rheumatic diseases

We identified 703 potential studies; 15 were relevant RCTs but only 6 reported cardiac failure 21 22 23 24 25 26. These 6 RCTs enrolled 8542 patients taking NSAIDs and 7208 taking placebo; 40 cases and 13 controls developed cardiac failure. There was no statistical heterogeneity between studies (χ2 = 5.37; df = 5; P = 0.37, I2 = 6.9%). More patients receiving NSAIDs developed cardiac failure (Fig. 2) (OR 2.31; 95% CI 1.34, 4.00).

3.3. Cardiac failure in RCTs in arthritis

We identified 1777 potential studies; 243 were relevant RCTs but only 6 of these reported cardiac failure 27 28 29 30 31 32 33. These 6 RCTs enrolled 62,653 patients randomised to receive COXIBs or conventional NSAID; only one involved placebo 29; 177 patients developed cardiac failure. There was no evidence that COXIBs increased the risk of cardiac failure compared to conventional NSAIDs (OR 1.14; 95% CI 0.85, 1.53), though one study (Fig. 3) showed that etoricoxib had greater risks than diclofenac (OR 1.65; 95% CI 1.11, 2.44) 32. There was statistical heterogeneity between trials (χ2 = 11.96; df = 5; P = 0.04; I2 = 58.2%) which in part may be explained by varying study methodology. The trials differed both in their active and control drugs and the patients they enrolled (some OA, some RA and some both). Furthermore the number of adverse events in 3 of the trials was small 27,29,30 — 6 episodes of cardiac failure in total, with two trials having only 1 each.

4. Discussion

Our meta-analyses of case-control studies, cohort studies and RCTs show in all settings that conventional NSAIDs increase the risk of cardiac failure by 30-100%. The absolute risk is small; less than one patient developed cardiac failure attributable to NSAIDs per hundred patient years of treatment. The results for COXIBs are heterogeneous and the data is incomplete. Rofecoxib (in observational studies) and etoricoxib (in one large RCT) may have higher risks than conventional NSAIDs. There is inadequate data to assess individual conventional NSAIDs or other COXIBs.

Several confounding factors limit our findings. Firstly, in observational studies “over the counter” NSAIDs like ibuprofen create difficulties estimating exposure 34. Secondly, adherence to medication varies across patient groups and clinical contexts 35. Thirdly, COXIBs were targeted at elderly patients with higher gastro-intestinal risks; they have multiple comorbidities and are prone to cardiac failure. Finally few RCTs published detailed information about cardiac failure. One reason is that it was rarely a pre-specified end-point. In addition most RCTs in arthritis were short term and involved small numbers of patients; patients in these trials would rarely develop cardiac failure, even if its frequency was increased by treatment. It is likely the risks of cardiac failure are under-estimated in RCTs in arthritis.

The studies varied in the patients they enrolled, particularly the presence of pre-existing cardiac failure. Patients with previous cardiac failure were excluded from five RCTs in arthritis 27,29, two RCTs in non-arthritic patients 22,25 and one case-control study 14. By contrast cohort studies entered patients who were elderly 17, taking diuretics 18, hypertensive 19 and had pre-existing cardiac failure 20. Observational studies variably evaluated inpatient and outpatient occurrences of cardiac failure 19, or first 12 or any admission for cardiac failure 17. Such variations explain the heterogeneity of results and indicate that estimates of the exact increase in risk attributable to NSAIDs must be treated with caution. In any event there is clear evidence that the risk of cardiac failure in patients receiving NSAIDs is increased in those with pre-existing cardiac failure.

The widespread use of NSAIDs 36, particularly in elderly patients likely to develop cardiac failure 37, makes NSAID-induced cardiac failure an important clinical concern. The risks are comparable to those with left ventricular hypertrophy, diabetes mellitus and valvular heart disease 38,39. Several studies excluded from our review support the link between NSAIDs and cardiac failure. Firstly, a cohort study of 7277 elderly patients found that NSAIDs increased relapses but not new cardiac failure 40. Secondly, an ecological study found that for each standard deviation of NSAID use the unadjusted relative risk of hospitalization for heart failure was 1.23 41. Thirdly, in 58,432 patients admitted to the hospital with myocardial infarctions there were more deaths in patients taking NSAIDs 42; many of these deaths may have been attributable to cardiac failure.

These results suggest it is prudent to avoid NSAIDs in patients with or at high risk of developing cardiac failure. This recommendation is supported by a secondary analysis of one large RCT 31, which showed 16 of 7664 (0.2%) patients taking ibuprofen or naproxen with low cardiovascular risk developed cardiac failure compared to 15 of 1463 (1%) with high risk factors 43. Interestingly in a small interview study of patients with cardiac failure, most were unaware of the risks of NSAIDs, though they would avoid them once educated about the adverse effects these drugs might have on their heart failure 44.

We conclude that all types of study show that NSAIDs increase the risk of cardiac failure, though the absolute risk is relatively small. Different drugs may have varying individual risks but overall conventional NSAIDs and COXIBs confer similar risks. We recommend NSAIDs to be used with caution by patients at high risk of developing cardiac failure, such as patients with diabetes mellitus, renal disease and receiving treatment with anti-hypertensives, as well as patients known to have cardiac failure.

Role of funding source

This research was supported by the ARC (Grants S0682 and P0572) and NHS R&D Support to University Hospital Lewisham and Kings College Hospital.

Conflict of interest

PAS and GHK — none.

DLS — support for international/local educational meetings and departmental research grants from companies making anti-inflammatory drugs.

No pharmaceutical company has made contributions to this paper.

Acknowledgement

We thank Fowzia Ibrahim for helpful comments concerning the statistics.