Patient perception of the effect of treatment with candesartan in heart failure. Results of the Candesartan in Heart failure: Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and morbidity (CHARM) programme

Abstract

Aims

To evaluate the effect of the angiotensin receptor blocker candesartan on patients' perception of symptoms, using the McMaster Overall treatment evaluation (OTE), in a broad spectrum of patients with chronic heart failure (CHF).

Methods and results

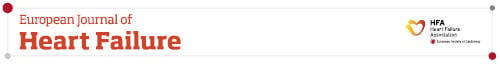

Patients with symptomatic CHF, randomised in the CHARM Programme in North America (n=2498), were studied. OTE was assessed at baseline, at 6, 14 and 26 months and the patient's final or closing visit. Patient's status was classified as “improved (score +1 to +7)”, “unchanged (score 0)” or “deteriorated (score–1 to –7)” at the end of the study compared to baseline. Both a simple “last visit carried forward” (LVCF) analysis and “worst rank carried forward” (WRCF) analysis (where patients who died were allocated the worst OTE score) were used. In the LVCF analysis, compared to placebo, more candesartan patients improved (37.7% versus 33.5%) and fewer worsened (10.8% versus 12.0%) in OTE (p=0.017). The WRCF analysis also showed better overall OTE scores with candesartan compared to placebo (p=0.029). There was no heterogeneity in the response to candesartan between the CHARM component trials or across four exploratory sub-groups (age, sex, NYHA class and beta-blocker).

Conclusions

Candesartan was shown to be better than placebo, when using the McMaster OTE to measure patient perception of treatment. More patients treated with candesartan reported improvement and fewer reported deterioration. This benefit was obtained when candesartan was added to extensive background therapy and is consistent with the benefits of candesartan on NYHA class, hospital admission for worsening heart failure and mortality.

1. Introduction

In addition to reducing mortality and morbidity, an ideal treatment for chronic heart failure (CHF) should lead to improvement in symptomatic well-being and functional capacity. We have recently shown that candesartan improves New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class in patients with CHF 1. NYHA classification, however, provides a measure of a clinician's assessment of a patient's functional limitation due to the characteristic symptoms of CHF 2. It is increasingly accepted that the patient's perspective on the effect of treatment is at least as important as a physician's assessment of the effect of treatment on functional status, especially in chronic diseases 3 4 5. Little is known about the effect of angiotensin receptor blockers on symptoms and functional limitation in CHF, in general, and about patient perception of this type of treatment, in particular. Thus, the objective of this analysis was to determine the effect of candesartan on patients' perception of change in overall symptoms and limitations.

2. Methods

2.1. The CHARM programme

The design, baseline findings and primary results of the CHARM Programme have been reported in detail 6 7 8 9 10 11. Briefly, the CHARM Programme consisted of three independent but related trials performed concurrently in which 7599 patients with NYHA class II–IV CHF, ≥4 weeks duration were randomised to placebo or candesartan (target dose 32 mg once daily). Patients were enrolled into the individual CHARM trials according to left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and baseline treatment with an ACE inhibitor. Patients with a LVEF≤0.40 who were intolerant of an ACE inhibitor were enrolled in “CHARM-Alternative”. Patients with a LVEF≤0.40 and taking an ACE inhibitor were enrolled in “CHARM-Added”. Patients with NYHA Class II required a cardiovascular hospitalisation in the previous 6 months which had the effect of increasing the proportion of NYHA class III/IV patients in CHARM-Added. Patients with a LVEF>0.40 (with or without concomitant ACE inhibitor use) were randomised into “CHARM-Preserved”. The CHARM Programme was completed, as planned, two years after the last patient was randomised. Because the rate of recruitment varied between the CHARM trials, overall follow-up ranged from a median of 41 months in CHARM-Added, 37 months in CHARM-Preserved, and 34 months in CHARM-Alternative (38 months in the overall CHARM Programme). The primary outcome in the individual component-trials of the CHARM Programme was the composite of cardiovascular death or hospital admission with worsening heart failure, analysed by time to first event. The primary outcome of the overall CHARM-Programme was all-cause mortality (time to first event). Evaluation of the McMaster OTE questionnaire 12 (see below) in the overall CHARM-Programme was a pre-specified secondary outcome.

2.2. Measurement of treatment efficacy

The McMaster Overall Treatment Evaluation (OTE) questionnaire 12 was completed by patients randomised in Canada and the USA. Each patient was asked one question: “Since treatment started, has there been any change in your activity limitation, symptoms and/or feelings related to your heart condition=” The patient was asked to answer by checking one of 3 boxes (“better”, “about the same” or “worse”). If either “better” or “worse” were checked, the patient was then asked to say how much their condition had changed by checking one of seven boxes: “almost the same, hardly better (worse) at all”, “a little better (worse)”, “somewhat better (worse)”, “moderately better (worse)”, “a good deal better (worse)”, “a great deal better (worse)”, or “a very great deal better (worse)”. Thus, the score obtained (OTE score) ranged between −7 (worse) and +7 (better) on a 15-point scale, including 0 for no change. In the second part of the questionnaire, the patient was asked: “How important is this change (better/worse) to you in carrying out your daily activities= By daily activities, we mean both work outside the home, housework and normal physical activities e.g. sport, leisure activities, etc.”. The patient was asked to check one box on a 7-point scale: “not important”, “slightly important”, “somewhat important”, “moderately important”, “important”, “very important” or “extremely important” to assess the perceived importance of the change in the patient's daily activities.

2.3. Analysis of overall treatment evaluation

The OTE questionnaire was administrated at 4 time points during follow-up visits: 6, 14, 26 months and at the closing or final visit. The main efficacy variable was the overall effect of the treatment at the last or closing visit. The overall score was analysed using the stratified Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test for comparison of the two treatment groups. The data were stratified by CHARM study and in aggregate for the overall effect.

A test for heterogeneity across the component trials was also performed, using a permutation test. A “last visit carried forward” (LVCF) approach was used for the primary analysis, as in prior trials using this or similar questionnaires, to impute for missing data 3,13. With this method, the last available questionnaire was used if the one for the final visit was missing (because of withdrawal from the study or death). We also used a “worst rank carried forward” (WRCF) approach, in a supportive analysis. With this approach, the worst OTE score (i.e. −7) was substituted for the final visit if a patient died during the study. The following example illustrates both methods: if a patient stated that he/she was “moderately better” at the visit 7 but subsequently died, his/her OTE score (+4) showing improvement would be carried forward to the final visit in the LVCF approach. Using the WRCF approach, a score of −7 (the worst possible score), would be substituted at the final visit.

We examined the effect of candesartan on OTE in the same four exploratory subgroups described in our prior report of the effect of candesartan on NYHA class i.e. men compared to women, older compared to younger patients, those in NYHA class II compared to III/IV at baseline and those not taking and taking beta-blockers at baseline 1. These analyses were performed using a permutation test for heterogeneity within subgroups.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline characteristics

The OTE questionnaires were completed by 2498 patients (33% of all CHARM patients). A total of 605 patients (30%) in CHARM-Alternative, 872 patients (34%) in CHARM-Added, and 1021 patients (34%) in CHARM-Preserved completed the questionnaire. Baseline characteristics of the patients in this ancillary study are shown in Table 1 and were broadly similar to those of patients in the overall CHARM Programme 11.

| CHARM-Alternative (n=605) | CHARM Added (n=872) | CHARM-Preserved (n=1021) | CHARM Overall (n=2498) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (yr) | 66.1 | 63.7 | 66.5 | 65.4 |

| Female (%) | 32.2 | 23.2 | 42.3 | 33.2 |

| LVEF | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.50 | 0.40 |

| NYHA class (%) | ||||

| II | 45.6 | 19.0 | 47.6 | 37.1 |

| III | 52.7 | 78.8 | 50.3 | 60.8 |

| IV | 1.7 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 2.0 |

| Medical history (%) | ||||

| Previous MI | 62.0 | 57.5 | 44.1 | 53.1 |

| Angina pectoris | 63.8 | 60.9 | 63.7 | 62.7 |

| Hypertension | 64.3 | 57.1 | 75.7 | 66.5 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 32.4 | 35.2 | 39.8 | 36.4 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 25.0 | 26.6 | 30.3 | 27.7 |

| Stroke | 10.4 | 9.9 | 10.6 | 10.3 |

| CABG | 36.2 | 33.5 | 28.8 | 32.2 |

| PCI | 23.5 | 18.7 | 21.3 | 20.9 |

| Treatment (%) | ||||

| ACE inhibitor | 0.2 | 100.0 | 26.9 | 46.0 |

| Beta-blocker | 57.4 | 54.9 | 58.2 | 56.8 |

| Spironolactone | 20.3 | 15.9 | 9.8 | 14.5 |

| Digitalis glycoside | 58.0 | 70.8 | 34.2 | 52.7 |

- a LVEF=left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA=New York Heart Association; MI=myocardial infarction; CABG=coronary artery bypass grafting; PCI=percutaneous coronary intervention.

3.2. Completeness of data

Of the 2498 patients in this analysis, 479 patients (119 in Alternative, 224 in Added, 136 in Preserved) died by the end of the study. “Last visit” or “worst rank” was carried forward in 718 patients.

3.3. Effect of treatment on final OTE scores

In the overall CHARM Programme, the distribution of OTE scores was more favourable in the candesartan group than in the placebo group (p=0.017), using the LVCF approach, as illustrated in Table 2a and fig. Fig. 1(a). The WRCF analysis confirmed this beneficial effect of candesartan (p=0.029, Table 2b and fig. Fig. 1(b)).

| CHARM-Alternative (n=605) | CHARM-Added (n=872) | CHARM-Preserved (n=1021) | CHARM-Overall (n=2498) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candesartan | Placebo | Candesartan | Placebo | Candesartan | Placebo | Candesartan | Placebo | |

| Deterioration (%) (Scores −7 to −1) | 9.0 | 9.9 | 13.0 | 11.7 | 10.0 | 13.9 | 10.8 | 12.0 |

| No change (%) (Score 0)* | 50.8 | 53.9 | 48.4 | 54.4 | 54.4 | 54.7 | 51.4 | 54.4 |

| Improvement (%) (Scores +1 to +7) | 40.2 | 36.1 | 38.3 | 33.9 | 35.6 | 31.6 | 37.7 | 33.5 |

- * For clarity, except for this category, OTE scores have here been grouped in categories covering 7 scores, defining either deterioration or improvement. The statistical analyses have however included all 15 possible scores on the OTE scale. The total of each column may exceed 100% because of rounding.

| CHARM-Alternative (n=605) | CHARM-Added (n=872) | CHARM-Preserved (n=1021) | CHARM-Overall (n=2498) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candesartan | Placebo | Candesartan | Placebo | Candesartan | Placebo | Candesartan | Placebo | |

| Deterioration (%) (Scores −7a to −1) | 24.3 | 30.0 | 35.5 | 32.7 | 20.2 | 24.3 | 26.4 | 28.6 |

| No change (%) (Score 0)* | 40.9 | 40.1 | 33.5 | 40.7 | 48.7 | 48.8 | 41.4 | 43.9 |

| Improvement (%) (Score +1 to +7) | 34.8 | 30.0 | 31.0 | 26.8 | 31.2 | 26.8 | 32.1 | 27.5 |

- a In this analysis, a patient who died during the course of the study was allocated an OTE score of −7 (worst possible score) and this was carried forward to end of study. The total of each column may exceed 100% because of rounding.

- * For clarity, except for this category, OTE scores have here been grouped in categories covering 7 scores, defining either deterioration or improvement. The statistical analyses have however included all 15 possible scores on the OTE scale.

There was no significant difference in the effect of candesartan on OTE across the component trials (test for heterogeneity p=0.11).

A higher percentage of patients who were randomised to candesartan perceived an improvement in overall symptoms compared with those randomised to placebo, using the LVCF approach (37.7% vs. 33.5%, Table 2a). In the candesartan group, the improvement was ranked by patients as moderate or greater (moderately, a good deal, a great deal or a very great deal better i.e. +4 to +7) in 27.6% compared to 23.9% in the placebo group (data not shown). In the WRCF analysis, these proportions were 32.1% (moderate or greater 24.3%) and 27.5% (20.2%), respectively (Table 2b).

Approximately half of the patients did not notice a change in their symptoms between randomisation and the end of the study.

Overall, 10.8% of candesartan treated patients reported deterioration in OTE score, compared to 12.0% in the placebo group, using the LVCF approach. In the candesartan group this deterioration was ranked by patients as moderate or greater (i.e. −4 to −7) in 7.4% compared to 8.6% in the placebo group. In the WRCF analysis, these proportions were 26.4% (moderate or greater 24.3%) and 28.6% (26.1%), respectively.

3.4. Patients' perception of the significance of the change in their condition

Patient-rated perception of the change in their condition after treatment was commenced is summarised in Table 3. Of patients reporting an improvement in their condition, in the candesartan group 51.3% considered this improvement to be very or extremely important compared to 46.4% in the placebo group, using the LVCF approach (p=0.148). Using a WRCF approach, these proportions were 53.8%, and 49.1% (p=0.209).

| CHARM trials* | Last visit carried forward approach, % (% vi, ei) | Worst rank carried forward approach, % (% vi, ei) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candesartan | Placebo | Candesartan | Placebo | |

| Alternative (n=231) | 76 (57) | 74 (45) | 77 (59) | 76 (47) |

| Added (n=316) | 77 (48) | 68 (45) | 80 (50) | 73 (49) |

| Preserved (n=343) | 75 (51) | 75 (49) | 76 (53) | 74 (51) |

| Overall (n=890) | 76 (51) | 73 (46) | 78 (54) | 74 (49) |

- * n here is the total number of patients improved in each component trial and in the overall CHARM programme. This analysis was only performed on data from patients who were improved at the end of the study, according to their OTE score (scores +1 to +7). Proportions represent patients for whom this improvement was perceived as important, very important (vi) or extremely important (ei) (and, in brackets, very important—vi or extremely important—ei).

3.5. Effect of treatment in exploratory sub-groups

The effect of candesartan in the four subgroups is shown in Table 4a,b. There was no heterogeneity of the effect of candesartan across these subgroups, patients in each treated with candesartan reporting a better overall OTE than those treated with placebo.

| Groups | Deteriorated (%) Scores −7 to −1 | Unchanged (%) Score 0 | Improved (%) Scores +1 to +7 | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candesartan | Placebo | Candesartan | Placebo | Candesartan | Placebo | ||

| All patients | 10.8 | 12.0 | 51.4 | 54.4 | 37.7 | 33.5 | N/A |

| Gender | |||||||

| Males | 10.1 | 12.8 | 53.8 | 54.7 | 36.0 | 32.5 | 0.996 |

| Females | 12.1 | 10.9 | 46.6 | 53.7 | 41.4 | 35.6 | |

| NYHA baseline | |||||||

| II | 6.8 | 10.5 | 52.9 | 56.2 | 40.4 | 33.4 | 0.530 |

| III–IV | 13.2 | 13.0 | 50.6 | 53.4 | 36.2 | 33.5 | |

| Age | |||||||

| <75 years | 9.4 | 11.5 | 50.9 | 52.3 | 39.7 | 36.1 | 0.894 |

| ≥75 years | 15.2 | 13.7 | 53.0 | 61.3 | 31.8 | 24.7 | |

| B-blockers at baseline | |||||||

| No B-blockers | 10.4 | 12.3 | 52.1 | 56.2 | 37.5 | 31.4 | 0.881 |

| B-blockers | 11.2 | 11.9 | 50.9 | 53.0 | 38.0 | 35.1 | |

- a p-value: test for heterogeneity.

- b N/A: non-applicable.

- c Overall treatment evaluation (OTE) at end of study using last visit carried forward (LVCF) approach: comparison of the candesartan and placebo groups, for the four exploratory subgroups. For clarity, the OTE scores have been grouped into three categories (“deteriorated”, “unchanged” and “improved”).

| Groups | Deteriorated (%) Scores −7 to −1 | Unchanged (%) Score 0 | Improved (%) Scores +1 to +7 | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candesartan | Placebo | Candesartan | Placebo | Candesartan | Placebo | ||

| All patients | 26.4 | 28.6 | 41.4 | 43.9 | 32.1 | 27.5 | N/A |

| Gender | |||||||

| Males | 27.2 | 31.4 | 42.8 | 42.4 | 30.1 | 26.0 | 0.932 |

| Females | 25.3 | 22.5 | 38.6 | 47.0 | 36.0 | 30.4 | |

| NYHA baseline | |||||||

| II | 16.5 | 21.8 | 47.3 | 50.5 | 36.1 | 27.8 | 0.404 |

| III–IV | 32.4 | 32.5 | 37.9 | 40.1 | 29.5 | 27.5 | |

| Age | |||||||

| <75 years | 23.6 | 26.3 | 42.3 | 43.5 | 34.0 | 30.1 | 0.990 |

| ≥75 years | 35.9 | 35.4 | 38.7 | 45.3 | 25.6 | 19.1 | |

| B-blockers at baseline | |||||||

| No B-blockers | 28.3 | 30.3 | 40.4 | 43.6 | 31.3 | 26.1 | 0.990 |

| B-blockers | 25.3 | 27.3 | 42.2 | 44.1 | 32.6 | 28.6 | |

- a p-value: test for heterogeneity.

- b N/A: non-applicable.

- c Overall treatment evaluation (OTE) at end of study using worst rank carried forward (WRCF) approach: comparison of the candesartan and placebo groups, for the four exploratory subgroups. For clarity, the OTE scores have been grouped into three categories (“deteriorated”, “unchanged” and “improved”). In this analysis, a patient who died during the study was allocated an OTE score of −7 (worst possible score) and this was carried forward to the end of the study.

4. Discussion

In the present analysis of CHARM, candesartan improved patient-reported well-being, based on a self-assessment questionnaire which asked about “activity limitation, symptoms and/or feelings related to your heart condition.” This supports our earlier finding from CHARM that candesartan improved physician-reported patient well-being, as shown by better overall NYHA functional class. In turn, these observations are consistent with the reduction in hospital admission for heart failure and cardiovascular death obtained with candesartan therapy in the CHARM Programme. Collectively, these other clinical benefits of candesartan provide internal validation of the OTE within the CHARM Programme.

Increasingly, assessment of the patient's perception of treatment is felt to be important 3,5,17. In clinical practice, incorporating the patient's view is associated with greater satisfaction with care, better adherence to treatment and maintenance of good professional–patient relationships 4. Consequently, evaluation of the patient's assessment of the effectiveness of treatment should also be an important objective of clinical trials 4.

The OTE is one of a small number of simple questionnaires designed to enable patients to report their perception of how their overall condition has changed since randomised treatment was commenced. Another example is the “patient global assessment” which uses a seven rather than fifteen point scale 13 14 15 16. The OTE was used in the Metoprolol CR/XL Randomized Intervention Trial in Congestive Heart Failure (MERIT-HF) study 3. Interestingly, in MERIT-HF and the earlier carvedilol studies, the OTE and patient global assessment showed improvement with beta-blocker treatment compared to placebo whereas a more conventional serial measure of quality of life did not 13.

CHARM-Added is probably the trial with most similarities to MERIT-HF but comparison of these two studies is difficult for three reasons. Firstly, the background therapy against which the new treatment was being tested was very different. In MERIT-HF, 95% of patients were taking an ACE inhibitor or ARB and 8% spironolactone; none were taking a beta-blocker. In CHARM-Added (n=2548), all patients were taking an ACE inhibitor, 56% a beta-blocker and 17% spironolactone. Secondly, the proportion of patients with NYHA class II (41% in MERIT-HF and 24% in CHARM-Added) and class III/IV (59% and 76%) also differed between the two trials. Thirdly, the duration of follow-up was different in the two studies; in MERIT-HF the mean follow-up was one year and in CHARM-Added the median follow-up was 41 months. With a sicker patient population and longer follow-up, a greater risk of deterioration would have been predicted in CHARM-Added than in MERIT-HF and this was observed (11.7% of the placebo and 13.0% of candesartan group deteriorated compared to 10% of the placebo group and 9.8% of the metoprolol CR/XL group). Similarly, improvement (or maintained improvement) might be less likely during the longer follow-up in CHARM-Added and, again, this was observed (33.9% of the placebo and 38.3% of candesartan group compared to 40% of the placebo and 50% of the metoprolol CR/XL group). Interestingly, however, the sicker patients in CHARM-Added were more likely to rate their improvement with active therapy as important, very important or extremely important (68% of the placebo and 77% of the candesartan compared to 72% of both treatment groups in MERIT-HF). Additionally, improvement in the OTE with metoprolol CR/XL, consistent with the other clinical benefits of this beta-blocker in the MERIT-HF trial, provides external validation of this instrument (as, indirectly, did the findings with the patient global assessment in prior studies with carvedilol) 13.

The favourable effect of candesartan measured with the OTE was observed when using both a LVCF approach and a WRCF approach. The latter type of analysis has not been reported with this instrument before. Because both types of analyses have advantages and disadvantages, we believe that the best approach is to use both. Clearly, carrying forward an “improved” score from four months to the end of a 38 month trial, in a patient who died after 8 months, can be criticised. Treating all deaths in the same way may not be appropriate either. For example, a sudden unexpected death in a patient who had improved on treatment and had been feeling well for some time is different than a death due to progressive pump failure after a prolonged period of symptomatic worsening.

It is notable that this simple, “retrospective,” measure of treatment effect (and other related instruments such as “patient global assessment”) does seem to effectively distinguish active from placebo therapy in CHF, whereas more sophisticated serial measures of symptoms and quality of life have not consistently done so (making “validation” of the OTE against other measures of patient well-being in CHF difficult) 3,4,13. Indeed, there is evidence that “retrospective” measures of treatment effect (i.e. ones which ask the patient to compare how they currently feel compared to a previous time point) are more sensitive than conventional serial measurements (where the patient is asked how they feel at a number of time points and change is measured by subtracting these scores) in other conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis, where sensitive conventional serial measures of patient well-being are available 4,17. Retrospective change scores may also correlate more strongly with patients' satisfaction with treatment 3,4. It is also notable that this method of assessing response to treatment corresponds most closely to what is done in ordinary clinical practice i.e. the health care professional usually asks the patient how he or she feels compared to the last time they met.

As with any study of this type, there are limitations. One, the most appropriate method of analysis, has already been discussed. Our data were collected in Canada and the USA only. Though OTE tells us about how patients feel their condition has changed, it does not give any qualitative or quantitative description of patients' baseline symptoms or functional limitation. Furthermore, the large “placebo-effect” makes differentiation from active treatment difficult. There is no physician counterpart to the patient questionnaire so no comparison of physician and patient perception of change can be made.

In conclusion, the angiotensin receptor blocker candesartan was shown to be better than placebo in the CHARM Programme, when using the McMaster OTE to measure patient perception of treatment. More patients treated with candesartan reported improvement and fewer reported deterioration. Of those reporting improvement, more reported this to be of importance to them in the candesartan group. There was no evidence of heterogeneity in the treatment benefit of candesartan across the component trials. This benefit was obtained when candesartan was added to extensive background therapy and is consistent with the benefits of candesartan on NYHA class, hospital admission for worsening heart failure and cardiovascular mortality.