Impact of sleep-related breathing disorders on health-related quality of life in patients with chronic heart failure *

Abstract

Background

Quality of life in patients with chronic heart failure (HF) is often severely compromised. Sleep-related breathing disorders (SRBD) like Cheyne–Stokes Respiration (CSR) or obstructive sleep apnea (OSAS) are often observed in patients with severe HF resulting in fragmentation of sleep, excessive daytime sleepiness and an increased mortality. While an apnea/hypopnea-index (AHI) >30/h represents an independent predictor of poor prognosis, clinical relevance of even minor SRBD with an AHI <30/h remains unclear with respect to quality of life, exercise capacity or depression rate.

Methods

Sixty-nine consecutive ambulatory patients with stable HF (NYHA II–III, EF 25%) underwent two night polygraphies with a six-channel ambulatory recording. Spiroergometry was performed, and patients were examined for sleep quality (PSQI), depressed mood (BDI) and health-related quality of life (SF-36). The data were compared to 10 age-matched healthy controls and 11 patients with OSAS (AHI 14–29/h) not suffering from HF.

Results

Fifty-one patients completed follow up. 52% were positively diagnosed for SRBD (AHI 16–30/h: 12 patients CSR, 5 patients OSAS, 9 patients mixed); 25 patients (48%) showed no relevant SRBD. Patients with HF and SRBD had lower quality of life than patients without SRBD and HF. The severity of SRBD as indicated by the AHI significantly correlated with quality of life measures: Bodily pain, physical functioning and social functioning showed largest impairment in patients with HF and SRBD. Furthermore, elevated depression rates in correlation to the AHI were only observed in patients with SRBD similar to patients with OSAS without HF.

Conclusion

Even minor SRBD in patients with HF independently influence quality of life and correlate with estimation of depression and sleep disturbances.

1. Introduction

Sleep complaints are common in patients with chronic heart failure (HF), and they include fragmentation of sleep, excessive daytime sleepiness, and increased mortality 1,2. In HF, sleep-related breathing disorders (SRBD) like central sleep apnea with Cheyne–Stokes respiration (CSR) or obstructive apnea (OSAS) are often observed 3 4 5. CSR is characterized by recurrent phases of central apneas during sleep alternating with a crescendo–decrescendo ventilation 3,6. It is associated with an increased incidence of atrial fibrillation and ventricular arrhythmias.

Increased peripheral and central chemosensitivity, prolonged circulation time, and reduced blood gas buffering capacity are the major factors contributing to the pathology 10,11. However, the exact pathophysiologic mechanism is not yet clear. Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) reduces the severity of CSR and obstructive apnea and cardiac arrhythmia 12 13 14 with positive effects on daytime sleepiness and cardiac function 15,16. In the general population, OSAS is more common than central sleep apnea, and it is associated with decreased health-related quality of life and depression 17. The effect of SRBD in patients with HF on quality of life or depression has not been evaluated. It is known that an apnea/hypopnea-index (AHI) of >30/h in HF is an independent predictor of poor prognosis 3, possibly due to adverse effects on heart rate and the incidence of ventricular arrhythmias 18,19. But the clinical relevance of less severe SRBD in heart failure (AHI <30/h) remains unclear in respect to quality of life, depression scores, or indication for treatment and it is hypothesised that even minor breathing disorders show negative influence on these parameters in patients with HF, too.

2. Methods

2.1. Patients

Sixty-nine ambulatory patients of our clinic (>18 years old), referred consecutively for the evaluation of HF or consideration of heart transplantation, were screened over 8 months.

HF was confirmed by left ventricular dysfunction (LVEF <35%) and impairment of exercise capacity (maximal VO2 <25 ml/min/kg). The etiology of heart failure was defined by cardiac catheterisation in all patients. Left ventricular ejection fraction was evaluated by biplane transthoracic echocardiography at the day of polygraphy.

Exclusion criteria were exercise-limiting diseases like peripheral vascular disease or degenerative joint disease, relevant pulmonary disease like chronic obstructive lung disease, acutely decompensated heart failure, known lung disease, stroke, the presence of severe associated disease, known depression or psychotic disorders, use of sedatives or inability of exercise tests or exercise tests that were limited by myocardial ischemia. All patients gave their informed consent before entry into the study. The data on quality of life and sleep quality was compared to 10 age-matched healthy controls (age 62±6 years, 4 females, 6 males, BMI 23±4) and 11 patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSAS) from our pulmonary department (AHI 14–29/h measure by one-night polygraphy, BMI 27±5, age 55±7, 8 male, 3 female) not suffering from any heart failure as evaluated by 2-D echocardiography.

2.2. Exercise test

A standard bicycle exercise protocol was used in all patients with HF with and without SRBD to determine peak oxygen uptake and O2-uptake at the anaerobic threshold.

Exercise began with 10 W after a 2-min unload period, followed by a ramp protocol with increment of 10 W/min. Oxygen uptake, CO2-production and ventilation per minute were measured using a breath-by-breath gas analysis (Jäger Oxygon, Würzburg, Germany). A 12-lead electrocardiogram was continuously recorded to exclude significant myocardial ischemia. Mean blood pressure was recorded by a cuff sphygmomanometer. Peak oxygen uptake (VO2 max) was determined at the highest value in the terminal phase of exercise, the O2-uptake at the anaerobic threshold (VO2-AT) was determined by the V-slope method.

2.3. Sleep study

All patients with HF underwent two overnight polygraphies after the ambulatory exercise testing. SRBD were established by a validated six-channel ambulatory recording unit 35 (SOMNOCHECK©, WEINMANN, Germany) at home taking into account the usual sleeping habits of the patients.

The sleep study consisted of a continuous polygraph recording that measured nasal/oral airflow and from non-invasive leads measuring separately abdominal and chest wall movements, oxygen saturation, heart rate, tracheal sounds (microphone), and body position.

According to the commonly used clinical criteria 20, a breathing event was defined as abnormal if either a complete cessation of airflow lasting >10 s was observed (apnea) or if a reduction in respiratory airflow of >50% of the airflow lasting >10 s associated with a desaturation >3 % could be discerned (hypopnea). CSR was defined by recurrent phases of absence of airflow associated with absence of chest-wall motion followed by a crescendo–decrescendo ventilation. Obstructive apnea was defined as absence of airflow in the presence of paradoxical chest-wall motion.

The average number of episodes of apnea and hypopnea per hour (AHI) was calculated, and the mean and minimum oxygen saturations during the night were determined. A sleep-related breathing disorder was diagnosed if the apnea/hypopnea index was >5/h 21,22.

2.4. Clinical ratings: self-report assessments

All subjects completed self-rating questionnaires assessing mood, sleep quality, and health-related quality of life:

- The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) represents a widely used self-report instrument to detect depressive symptoms and to screen subjects with possible clinical depression 23. From several versions, we administered a German translation of the BDI version with 21 statements rated from 0 to 3 corresponding to the original version 24. Scores of ≥10 are indicative of mild depression, and a score of ≥20 suggests moderate-to-severe depression. This moderate-to-severe cutoff enables to detect depressive syndromes.

- The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) is a self-rated questionnaire assessing sleep quality and disturbances retrospectively over a 1-month time interval 25. There are 19 individual items which generate seven scores: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction. Good sleepers are distinguished by the resulting global PSQI sum score which is found to be greater than 5 in the so-called “poor” sleepers.

- For investigation of the health-related quality of life, we applied the German version 26 of the 36-item short-form (SF-36) which was designed for self-administration for multipurpose: in clinical practice, research, and also in general population surveys. The SF-36 consists of one multi-item scale assessing eight health concepts perceptions 27: (1) limitations in physical activities because of health problems; (2) limitations in social activities because of physical or emotional problems; (3) limitations in usual role activities because of physical health problems; (4) bodily pain; (5) general mental health (psychological distress and well-being); (6) limitations in usual role activities because of emotional problems; (7) vitality (energy and fatigue); and (8) general health perceptions.

2.5. Statistics

Values are presented as medians (95% confidence interval)±standard deviation. All P values reported are two-tailed. Statistical analyses were performed with the computer software SPSS for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). ANOVA was used to compare the means of normally distributed variables between ‘good sleepers— (global PSQI <5) and ‘poor sleepers— (global PSQI ≥5), healthy volunteers and OSAS-patients. The relationship between quality of life measures and parameters indicative of the severity of sleep-related breathing disorders was explored first by bivariant regression analysis (Spearman rank correlation coefficients). To determine the independent association of quality of life measures with the severity of sleep-related breathing disorders in the presence of other factors affecting quality of life, stepwise linear regression analysis was performed in a second step. The multivariate statistical model was built in steps and was designed to select only factors that correlated with the quality of life measures at a level of significance <0.05 for the final multiple regression model. Multiple stepwise linear regression analysis (‘forward stepwise entry—) was performed with quality of life indicators as the dependent and AHI, EF, variable body mass index and age as independent variables. The regression analysis disclosed that the significant correlations between the AHI index and most of the scores of the quality of life measures persisted even after correction for the possible risk factors tested.

3. Results

3.1. Patients

Fifty-one patients finished all tests and were included in the analysis (36 males, 15 females). The characteristics are given in Table 1. As confirmed by clinical examination, all patients were in a clinically stable condition (in the SRBD group n=17 NYHA II, n=9 NYHA III; in the non-SRBD-group n=23 NYHA II, n=2 NYHA III) classified according to New York Heart Association functional class) for at least 2 months, and they showed no acutely decompensated heart failure. All patients had exertional dyspnea. HF-atiology was ischemic in 13 and non-ischemic in 38 patients. All patients were on optimized medical HF-therapy (20 patients β-blockers, 23 patients angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, 11 patients aldactone, 26 patients diuretics, and 13 patients digitalis in the SRBD-group; 18 patients β-blockers, 22 patients angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, 25 patients diuretics, and 14 patients digitalis in the non-SRBD group) which were unchanged for at least 6 weeks prior to study entry. There were no differences with regard to age, body mass index, or ejection fraction between HF patients with and without SRBD (Table 1).

| HF and SRBD (n=26) | HF without SRBD (n=25) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male/Female | 18/8 | 18/7 | n.s. |

| Age (years) | 61±11 | 52±10 | n.s. |

| BMI | 26±4 | 25±3 | n.s. |

| EF | 23±7 | 26±6 | n.s. |

| VO2 max | 13.8±4 | 17±7 | 0.04 |

| VO2 AT | 10.6±2 | 12±4 | n.s. |

3.2. Exercise tests

All patients with HF underwent bicycle spiroergometry. Table 1 shows the results of exercise test. All patients terminated exercise testing because of exertional dyspnea. All reached the anaerobic threshold. All patients showed reduction of exercise capacity due to chronic heart failure. VO2 AT was not different between the groups whereas VO2 max was reduced in patients with SRBD respiration (see Table 1).

3.3. Evaluation of depression (BDI)

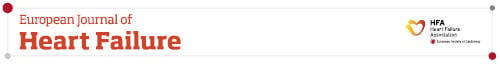

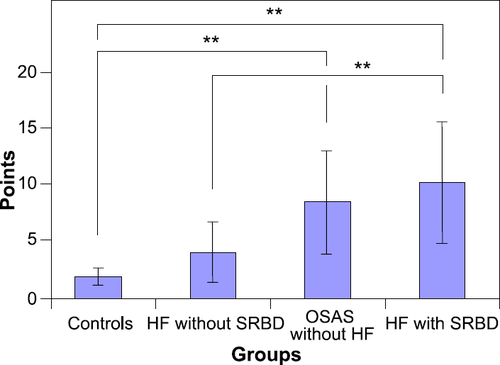

All patients completed the Beck Depression Inventory. In patients with HF without SRBD, median score was 4.63±2 points (range 0–8). In patients with HF and SRBD, the median score was 11.6±5 (range 8–17, p=0.0001). There were no differences between patients with HF and CSR, OSAS or mixed apnea. 31% (8 patients: 5 men, 3 women) met the criteria for some syndromal depression on the basis of a score >10 (0 patients >20 points) similar to patients with OSAS not suffering from HF reaching a score of 9.7±5 (fig. Fig. 1). There was a significant correlation in patients with HF and SRBD between the AHI and the severity of depression (r=0.88, p=0.0001, fig. Fig. 2) There were no correlations between BDI and age, BMI, EF, VO2 max or VO2 AT.

3.4. Sleep study

Twenty-six patients (52%) of the 51 patients with HF were positively diagnosed for SRBD by polygraphy at home for two nights with an AHI ≥5/h: CSR was diagnosed in 12 patients, 5 patients showed OSAS, 9 patients showed mixed SRBD. There were no differences between patients with HF and CSR, HF with OSAS or HF with mixed apnea. The median AHI was 18±8/h (range 8–30/h, no patient >30/h), the minimum oxygen saturation was 81±3% (range 74–87 %). The remaining 25 patients (48%) showed no relevant SRBD (AHI <5/h). Patients with and without SRBD did not differ with respect to age, weight, smoking habits, use of alcohol, associated diseases (esp. diabetes), or prescribed medication including β-blockers compared to patients with HF without SRBD. There were no correlations between AHI and age, BMI, ejection fraction, VO2 max or VO2 AT.

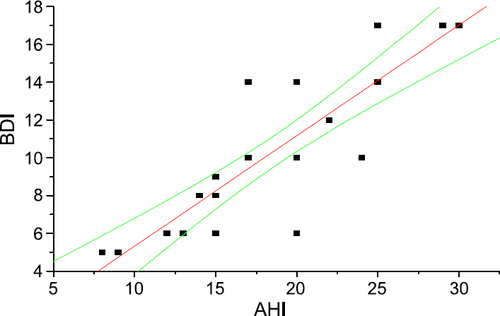

3.5. Evaluation of sleep quality (PSQI)

The mean (S.D.) global PSQI scores in patients with and without SRBD are shown in fig. Fig. 3. The global PSQI score ranged in patients with HF and SRBD from 8 to 17, and 37% were poor sleepers (global PSQI >10). There were no differences between patients with HF and CSR, OSAS or mixed apnea. In comparison to the group without SRBD, the patients with SRBD differed significantly in all subjective sleep measures. This pattern corresponded to scores in patients with OSAS without HF (fig. Fig. 3). The global PSQI score correlated with the AHI (r=0.529, p=0.005), BDI (r=0.71, p=0.001), physical functioning (r=−0.428, p=0.02) and health (r=−0.42, p=0.03). The PSQI also correlated with the VO2 max (r=−0.46, p=0.017).

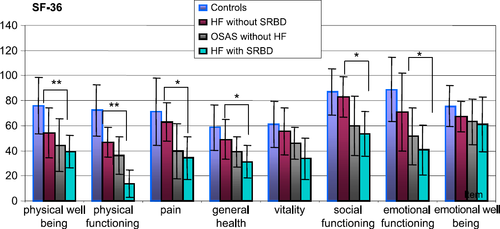

3.6. Evaluation of health-related quality of life (SF-36)

Patients with HF and SRBD had a significantly lower quality of life in six out of eight subjective measures compared to patients with HF without SBRD (fig. Fig. 4). There were no differences between patients with HF and CSR, HF with OSAS or HF with mixed apnea. In particular, bodily pain, physical functioning and emotional functioning showed the largest impairment in the study group with HF with SRBD as compared to HF without SRBD. This corresponds to the quality of life in patients with OSAS without any heart condition (fig. Fig. 4). In patients with HF and SRBD, there were significant correlations between the AHI and the following scores of the SF-36: physical well being (r=−0.7, p=0.0001), physical role functioning (r=−0.53, p=0.006), pain (r=−0.53, p=0.006), general health (r=−0.45, p=0.02), social functioning (r=−0.6, p=0.001), but not for emotional functioning, emotional well being or vitality. Table 2 shows the result of analysis for physical well being.

| Dependent variable | Forward stepwise linear regression: selected independent variables | Corrected r2 | Standardized β coefficients (last steep) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical well being | (1) AHI | Step 1: 0.38 | −0.64 | <0.001 |

| (2) BMI | Step 2: 0.17 | −0.45 | <0.05 | |

| (3) VO2 max | Step 3: 0.12 | 0.39 | <0.05 |

- a None of the other possible risk factors tested (EF, age, VO2 AT) was included in the stepwise multiple linear regression model because the significance level of 0.05 was exceeded.

4. Discussion

Although quality of life has been recognized as an important parameter in evaluating patients with HF, the association between SRBD, quality of life, and depression has not yet been addressed to our knowledge. Our findings suggest that SRBD has a major impact on quality of life, and disturbed sleep itself significantly contributes to depressive syndromes in patients with stable chronic heart failure. There were no differences between patients with HF and OSAS, HF with CRS or HF with mixed apnea in our study group, showing that the appearance of SRBD leads towards reduction of life quality. The correlation of the apnea/hypopnea index with most of the quality of life measures and depressive syndromes indicates that patients with AHI indices (in our group all below 30/h) estimated their impaired physical and emotional health status lower as opposed to patients without sleep-related breathing disorder. The data corresponds to patients with OSAS without any heart condition showing the psychophysiological impact of even an AHI <30/h in patients with HF suffering from minor SRBD.

As HF is a highly prevalent disorder that is associated with repeated hospitalizations, high morbidity, and high mortality, the present findings may have particular therapeutic implications for patients with severe impairment of quality of life and depressive states, which may be treatable if properly diagnosed as all groups were standardized for medical therapy. Consequently, it is of clinical importance to determine predicting factors for readmissions to hospital to reduce this likelihood. 35% of patients with HF and depressive states were readmitted to hospital within 1 year after discharge 28. Therefore, interventions to reduce readmission rates should also target the social and psychological management in all hospitalized patients. SRBD like CSR or OSAS in patients with stable chronic heart failure should be evaluated frequently even if their AHI is below 30/h.

HF and depression are independently known to result in physically decline and diminished functional capacity in the general population.

Turvey et al. 29 examined the rates and correlations of depressive symptoms and syndromal depression in people with heart failure in a community study of subjects aged 70 and older above. The study revealed that 11% met the criteria for syndromal depression, compared with 4.8% of people with other heart conditions and 3.2% of those without any heart condition.

Another report 30 of a population of hospitalized patients with HF showed a prevalence of depression in 20% for a current major depressive episode, 16% for a minor depressive episode, and 51% scored above the cutoff for some depression on the Beck Depression Inventory (≥10). In conclusion, depressive symptoms were common and unrelated to the severity of HF 31. Although depressed individuals tended to report reduced physical functioning as opposed to non-depressed individuals, objective assessment of energy expenditure was comparable. Depressed patients appeared to underestimate their functional ability, shown in our study by reduced maximal VO2 max. Subsequently, inaccurate assessment of functional status may result in longer hospitalizations or earlier hospital admissions 31.

Depressive disorders are known to be associated with a higher incidence of cardiac events like myocardial infarction or cardiac arrest in patients with known HF or coronary artery disease 30,32,33. The prevalence of depression (BDI of ≥10) in HF was found to be associated with cardiac events, longer hospitalizations, and adverse outcomes with an overall mortality of 7.9% at 3 months and 16.2% at 1 year 34,35.

Interestingly, although our HF patients with and without SRBD differed significantly in their depressive (BDI) scores they did not estimate their emotional well being differently as opposed to their emotional functioning. In the context of reduced quality of life (concerning physical well being, physical functioning, pain and social functioning), they seem to have a more functional, respectively, somatic-based concept of their own deficits rather than their subjective emotional state.

Despite advances in medical management of patients with HF, depression is an important independent predictor of death and should be carefully monitored and treated if necessary.

It remains to be seen whether nCPAP can preserve quality of life and depression in patients with stable HF and show an effect on rehospitalization rate and survival.

5. Study limitations

One limitation of the study is the use of a overnight polygraphy for evaluation for SRBD measurement without EEG, EMG or EOG. Although polysomnography is regarded as the gold standard ambulatory polygraphy like the applied device has the advantage of home recordings taking into account the usual sleeping habits of the patients 36.

Furthermore, the OSAS patients were screened with the same device as HF patients. The absence of heart disease was evaluated by echocardiography and medical history. Healthy volunteers were screened by PSQI and medical history for the absence of heart disease. No polygraphy was performed.

6. Conclusion

Sleep-related breathing disorders with even minor SRBD with an AHI <30/h in patients with heart failure independently influence quality of life and correlate with depressive states and sleep disturbances.