Mental health outcomes among patients from Fangcang shelter hospitals exposed to coronavirus disease 2019: An observational cross-sectional study

Abstract

Background

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is not only attacking physical health, but it is also increasing psychological suffering. This study aimed to observe the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health outcomes among patients with mild to moderate illness in Fangcang shelter hospitals.

Methods

We conducted an observational, cross-sectional study of 129 patients with mild to moderate illness from Jiangxia Fangcang shelter hospitals in Wuhan, China. The participants were assessed by quantifying their symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, and stressful life events and analyzing potential risk factors associated with these symptoms. Using correlation analysis, we examined associations between exposure to COVID-19 and subsequent psychological distress in response to the outbreak.

Results

In total, 49.6% of participants had depressive or anxiety symptoms. The depressive and anxiety symptoms were highly related to sleep disturbances and hypochondriasis (all r > 0.50, P < 0.01). The impact of the event was positively related to depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, sleep disturbances, hypochondriasis and life events (all r > 0.35, P < 0.01) but was negatively related to psychological resilience (r = −0.41, P < 0.01). The presence of the COVID-19 infection in this setting was associated with increased anxiety, depression and stress levels, and decreased sleep quality, and seriously affected patients’ quality of life as well as adversely affecting the course and prognosis of physical diseases.

Conclusion

The sleep quality, anxiety, and depression of COVID-19 patients in Fangcang shelter hospitals were significantly related to the impact of the epidemic.

Introduction

At the end of December 2019, a novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19), presenting as a cluster of acute respiratory illnesses, was first reported in China, and since then it has been rapidly transmitted to more than 180 countries around the world.1,2 COVID-19 was officially declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) on March 11, 2020.3 Apart from physical suffering, the outbreak of COVID-19 also causes substantial social and psychological stress, which puts victims at high risk for anxiety and depression. This is the case for the general public,4,5 students,6 and medical staff (especially for the frontline workers in the central epidemic area of Wuhan)7,8 as well as for those with confirmed or suspected cases of COVID-19.9 At the beginning of the epidemic, scientists did not have a clear understanding of COVID-19, and pressure enveloped society. The mental health problems of patients with COVID-19 can be particularly severe, with intense and uncontrollable feelings of anxiety, fear, worry, and/or panic.10 Mental health problems can interfere with diagnosis, lower treatment compliance, and worsen the outcome of subsequent treatment.11 Previous studies have shown that in other novel infectious disease epidemics, such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS),12,13 there were high rates of psychiatric symptoms, such as anxiety, depression and sleep disorders, which cause diminished quality of life and poor outcomes as well as substantial physical suffering.

The COVID-19 epidemic in Hubei Province, China, was managed with the creation of Fangcang shelter hospitals to isolate and treat patients with mild to moderate COVID-19 symptoms.14 This initiative was a novel public health concept. Fangcang shelter hospitals offered emotional and social support to help patients recover.15 The centralized treatment in Fangcang shelter hospitals also included treating patients with sleep disorders, including difficulty falling asleep, poor sleep, excessive dreams, and waking early.14,16 Some individuals struggled with lifestyle changes, and had to deal with uncertainty about recovery, worries about family health, or whether they could be infected again by neighbors, in addition to other factors. There were many sources of stress for these patients.

The current study aimed to evaluate mental health outcomes among patients with COVID-19 by quantifying the magnitude of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, and distress and by analyzing potential risk factors associated with these symptoms. Participants from Jiangxia Fangcang shelter hospital in the city of Wuhan, China were enrolled in this survey. This study provides a potential strategy for an assessment of the mental health problems of patients with mild to moderate illness, which can serve as important evidence to direct the promotion of mental health well-being among patients with COVID-19 in such settings.

Methods

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the First Teaching Hospital of Tianjin University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Approval number: TYLL2020 [K]-007). Informed consent was provided by all survey participants prior to their enrollment. Participants were allowed to terminate the survey at any time they desired. The survey was anonymous, and the confidentiality of the information was assured. No monetary rewards were given for completing the questionnaire.

Study design

An observational cross-sectional study was designed to assess levels of sleep quality, anxiety, depression, self-efficacy, stress, and social support, and the correlation between the levels of social support and mental health of the patients with mild to moderate illness from Jiangxia Fangcang shelter hospital of Wuhan, China. Data were collected online (www.h6world.cn) with a self-reported questionnaire that was measured using validated clinical questionnaires and scoring systems. All questionnaires were completed anonymously by the 129 participating patients with COVID-19.

Impact of the Self-Rating Scale of Sleep (SRSS)

The sleep questionnaire used in this study included the sleep condition self-rating scale (Self-Rating Scale of Sleep; SRSS).17,18 Detailed information about the scale is provided in the references. Factors that affected sleep are included in the questionnaire, which mainly consisted of the following aspects: sleep duration, difficulty falling asleep, early wake-up, nightmares, sleep quality, and the use of short-acting sleeping pills. A total score is derived by summing the individual item scores; the total scores range from 10 to 50. An SRSS score ≥23 points was considered to indicate sleep problems. A higher score indicates more severe sleep disturbance.

Mental health assessment

To assess anxiety and depression symptoms, the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)19 and 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7)20 served as screening and primary outcome measures. The PHQ-9 is a useful tool to detect both major depression and subthreshold depression. According to the PHQ-9, each item is rated from “not at all”, “several days”, “more than half the days” to “nearly every day”, with scores for mild, moderate, and severe depressive symptoms ranging from 5 to 9, 10–14, and 15–27, respectively. The Chinese version21 has been validated and is reliable for screening depression, with a cutoff score of 10. The GAD-7 is a self-rated scale to evaluate the severity of anxiety and has good reliability and validity. The scores of mild, moderate and severe anxiety symptoms range from 5 to 9, 10 to 14, and 15 to 21, respectively. The Chinese version has been validated and is reliable for screening anxiety, with a cutoff score of 7.

Impact on social and family support

The Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS)22 was used to investigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on social and family support (Cronbach's alpha of 0.87). The SSRS has been widely successful in its application to participants within the Chinese population23,24 and has been shown to have high reliability and validity. The SSRS comprises three subscales: subjective support (questions 1 and 3–5), objective support (questions 2 and 6–7), and utilization of social support (questions 8–10). The total SSRS score is the sum of the scores from the three subscales. Scores range from 13 to 66, with higher scores indicating a higher level of social support.

Impact of stressful life events

We used three scales to assess the mental health status of COVID-19 patients. The 7-item Whiteley Index (WI-7),25 the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC)26,27 and the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R)28 were used to assess changes in stress, which were due to illness, the resilience of patients, horrifying feelings, apprehensive feelings, helplessness feelings and distress because of the COVID-19 pandemic, respectively. The WI-7 scale was used to assess the severity of hypochondriasis and somatoform symptoms. There were seven items with five grades, with a total score ranging from 0 to 28 points. The scale contains two factors: disease concern and disease certainty. A higher score indicates more serious somatoform symptoms. The Chinese version of the WI-729 has good internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha = 0.73) and test-retest validity. The CD-RISC has been used widely to assess resilience in different populations (e.g., psychiatric patients, adolescents and elderly individuals) and has been reported to have good reliability and validity in some studies. The CD-RISC is a 25-item scale using a 5-point Likert-type response scale ranging from not true at all (0) to true nearly all of the time (4). The Chinese version of the CD-RISC30 has good internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha = 0.91) and test-retest reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient = 0.87). The IES-R is a self-reported measure used to assess the extent of traumatic stress (excessive panic and anxiety), including trauma-related distressing memories and persistent negative emotions resulting from the pandemic. The response to each question was scored 0 (not at all), 1 (rarely), 3 (sometimes) or 5 (often), with a lower score indicating a less stressful impact. Scale scores were formed for the three subscales, which reflect intrusion (8 items), avoidance (8 items), and hyperarousal (6 items), and showed a high degree of intercorrelation. A cut-off of the IES-R ≥26 was used to reflect moderate to severe impact.

Stressful life events related to the COVID-19 pandemic

We collected data on acute stressful events that occurred during the COVID-19 epidemic, including infection with COVID-19, critical illness, the death of a family member, a family member working on the front lines of the epidemic, financial difficulties or living difficulties, unemployment, discrimination, and other setbacks. A negative answer was scored zero. For the positive items, a 5-point Likert scale31,32 was used to indicate no influence, mild influence, moderate influence, severe influence and extremely severe influence. The total score ranges from 0 to 55, and the higher the score is, the more serious the impact of the event.

Statistical analysis

Initially, we examined whether the data were normally distributed using the one-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and a histogram plot. Differences between two groups were tested by Chi-square test, t-test and Mann–Whitney U test as applicable. Pearson's correlation or Spearman's correlation analysis was used to examine the correlation among depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, hypochondriasis, psychological resilience, the impact of events and social support. For multiple comparisons, the Bonferroni method was used to control type I error, and overall P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses except correlation analyses were conducted in SPSS version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Correlation analyses were performed in R software (version 3.6.3, https://www.r-project.org/) with the “corrplot” package (https://github.com/taiyun/corrplot).33

Results

Demographic characteristics

In this study, 129 participants completed the survey. The mean age of all participants was 43.8 ± 12.6 years old, and 62.0% of participants were male (Table 1). According to the cut-off of the surveys, 52 (40.3%) participants had depressive symptoms and 57 (44.2%) participants had anxiety symptoms. In total, 64 (49.6%) participants had depressive or anxiety symptoms. Comparisons were made between the non-symptoms group (n = 65) and the symptoms group (n = 64). There was no difference in age between the two groups, but participants with symptoms had a higher proportion of females than the non-symptoms group.

| Characteristics | Patients without symptom (n = 65) | Patients with symptoms (n = 64) | Statistical values | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 42.9 ± 13.4 | 44.8 ± 11.7 | −0.817a | 0.416 |

| PHQ-9, median (P25, P75) | 1.0 (0, 2.0) | 7.5 (5.0, 11.0) | −8.559b | <0.001 |

| GAD-7, median (P25, P75) | 0.5 (0, 2.0) | 7 (6.0, 9.5) | −9.595b | <0.001 |

| SRSS, mean ± SD | 18.5 ± 5.9 | 26.4 ± 7.8 | −6.565a | <0.001 |

| CD-RISC, mean ± SD | 30.5 ± 10.3 | 23.1 ± 9.3 | 4.273a | <0.001 |

| Life events, mean ± SD | 7.1 ± 4.2 | 10.4 ± 5.5 | −3.814a | <0.001 |

| SSRS, mean ± SD | 43.2 ± 8.4 | 40.9 ± 7.5 | 1.602a | 0.112 |

| Objective support, mean ± SD | 10.8 ± 3.4 | 9.6 ± 4.0 | 1.909a | 0.058 |

| Subjective support | 25.1 ± 4.6 | 24.3 ± 3.8 | 1.089a | 0.278 |

| Availability of support, mean ± SD | 7.2 ± 2.0 | 7.0 ± 1.8 | 0.557a | 0.579 |

| Length of stay (days), mean ± SD | 18.1 ± 5.2 | 18.0 ± 5.1 | 0.050a | 0.960 |

| Gender, n (%) | 4.262c | 0.039 | ||

| Male | 46 (70.8) | 34 (53.1) | ||

| Female | 19 (29.2) | 30 (46.9) | ||

| Clinical outcome, n (%) | 1.567c | 0.211 | ||

| Discharged | 51 (78.5) | 44 (68.8) | ||

| Transferred | 14 (21.5) | 20 (31.3) | ||

| Benzodiazepine use, n (%) | 2 (3.1) | 9 (14.1) | 4.989c | 0.026 |

| Whiteley-8, median (P25, P75) | 4.0 (1.0, 7.0) | 9.0 (7.0, 16.0) | –5.653b | <0.001 |

| Disease fears, median (P25, P75) | 2.0 (1.0, 3.0) | 4.0 (3.0, 7.0) | –5.618b | <0.001 |

| Disease concerns, median (P25, P75) | 1.0 (0, 2.3) | 3.0 (1.0, 5.0) | –4.208b | <0.001 |

| IES-R, median (P25, P75) | 16.0 (6.0, 24.0) | 27.0 (24.6, 40.5) | –6.309b | <0.001 |

| Avoidance, median (P25, P75) | 6.0 (3.0, 9.2) | 10.5 (8.0, 15.5) | –5.651b | <0.001 |

| Intrusion, median (P25, P75) | 6.0 (3.0, 8.0) | 12.0 (9.0, 16.5) | –6.421b | <0.001 |

| Hyperarousal, median (P25, P75) | 3.0 (1.0, 6.0) | 8.0 (6.0, 12.0) | –6.601b | <0.001 |

- a t-test.

- b Mann–Whitney U test.

- c Chi-square test. PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9; GAD-7: General Anxiety Disorder-7; SRSS: Self-Rating Scale of Sleep; CD-RISC: Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale; IES-R: Impact of Event Scale-Revised; SSRS: Social Support Rating Scale; SD: Standard deviation.

Among them, 11 patients took estazolam tablets, and 6 patients took Lianhua Qingwen capsules in addition to Qingfei Paidu decoction (QPD). In terms of treatment outcomes, 34 patients with COVID-19 nucleic-acid positive were transferred to a higher-level hospital for continued treatment when the Fangcang shelter hospital was closed. A total of 95 recovered patients were isolated at home after treatment, discharge and close observation.

Psychosocial factors

Higher levels of sleep disturbances, hypochondriasis, life stress, and impacts of events were found in patients with symptoms than in patients without symptoms (Table 1). We also found that patients with symptoms had a higher proportion of benzodiazepine use than patients without symptoms. After the Bonferroni method was used,34 the Whiteley-8 (disease fears and disease concerns) and IES-R (avoidance, intrusion and hyperarousal) subscales remained significant between the two groups. There were no differences in social support and its subscales, the length of stay, or clinical outcomes.

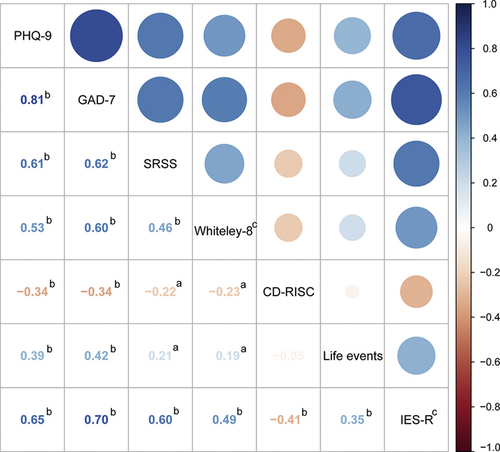

Correlation analyses

As shown in Fig. 1, depressive and anxiety symptoms were highly related to sleep disturbances and hypochondriasis (all r > 0.50, P < 0.01). The impact of the event was positively related to depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, sleep disturbances, hypochondriasis and life events (all r > 0.35, P < 0.01) but was negatively related to psychological resilience (r = −0.41, P < 0.01). In addition, psychological resilience was also negatively related to depressive and anxiety symptoms, sleep disturbances, and hypochondriasis.

Correlations of depressive and anxiety symptoms, sleep disturbances, hypochondriasis, psychological resilience, life stress and the impact of events. The color depth of number represents the correlation. aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01. cData were tested by Spearman's correlation analysis. PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9; GAD-7: General Anxiety Disorder-7; SRSS: Self-Rating Scale of Sleep; CD-RISC: Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale; IES-R: Impact of Event Scale-Revised. (For interpretation of the references to color/colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has severely affected China and many other parts of the world.1,35 Many patients with COVID-19 experience both physical suffering and great psychological distress.36,37 Some recent studies published in the Lancet38 have reported the clinical symptoms of patients infected with COVID-19 and have forecasted the spread of COVID-19. Our studies have reported the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health outcomes among patients with mild to moderate COVID-19 in Fangcang shelter hospitals and further quantified the magnitude of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, and distress by analyzing the potential risk factors associated with these symptoms.

During the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China, Fangcang shelter hospitals isolated thousands of patients.15,16 Because of the social isolation, perceived danger, uncertainty, physical discomfort, medication side effects, fear of virus transmission to others, and the overwhelmingly negative news portrayed in mass media coverage, patients with COVID-19 may have experienced loneliness, anger, anxiety, depression, insomnia, and posttraumatic stress symptoms, which could negatively affect their social and occupational functioning and quality of life.10,39 To date, no studies on the pattern of mental health and quality of life among COVID-19 patients in Fangcang shelter hospitals have been reported. Therefore, we conducted an online survey using the mental health scales to examine patterns of mental health symptoms in patients with mild to moderate COVID-19 symptoms in Fangcang shelter hospitals.

According to Wuhan municipal headquarters for the COVID-19 epidemic prevention and control requirements, all persons coming to the hospital should be first screened and isolated for COVID-19 and be classified into four categories: confirmed, suspected, patients with fever that cannot be ruled out at present, and close contact with confirmed patients.40 Confirmed patients with mild to moderate illness were isolated and treated in Fangcang shelter hospitals. The hospitals contained partitions that separated bed units into spaces resembling hospital rooms and wards, men and women living in different areas, but they could meet and communicate. If couples in a family were infected with the COVID-19, they were often assigned to the same shelter hospital, while other uninfected family members were isolated at home.

The mild-to moderate-confirmed patients with low-grade fever, dry cough, fatigue, and/or lung CT scanning with ground-glass opacities, and/or merely positive COVID-19 nucleic acid testing, were screened according to the Diagnosis and Treatment Protocol for Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia.41 All the patients were treated with QPD,42,43 which relieves symptoms and is a great consolation in the absence of special drugs and vaccines. We conducted psychological tests on all newly admitted patients after obtaining their consent. For patients who only had depressive or anxiety symptoms, we supplemented the Chinese herbal medicine granules on the basis of the decoction to relieve symptoms. When distributing medicines to patients, we explained in detail about the efficacy of the medicine, which has also a strong suggestive effect. For those patients diagnosed with anxiety or severe insomnia, the estazolam tablet dosage was 1 mg or 2 mg per night.44

This cross-sectional survey enrolled 129 respondents and revealed a high prevalence of mental health symptoms among patients with COVID-19 in Fangcang shelter hospitals in Wuhan, China. The incidence of most symptoms, especially sleep problems, exceeded 68.7% in all participants who reported difficulty with sleep onset and decreased motivation, and approximately 14.7% of all patients reported insomnia nearly every day on the PHQ-9. This finding may raise the importance of early attention to the mental health of patients during the COVID-19 pandemic.45,46 A total of 38.7% of all participants were women, and depression or anxiety was reported in 61.2% of the participants. Our findings further indicate that women reported more severe symptoms of depression, anxiety, and distress. The patients' anxiety about COVID-19 might have been related to the effect of the virus on changes in their sleep, hypochondriasis and life events.46-48 These results remind us that anxiety disorders are more likely to occur and to worsen in the absence of a supportive family environment.

Resilience is the ability of an individual to resist stress by a “self-adjusting mechanism” and to successfully use both internal and external protective factors.49 The influencing factors are multidimensional, including individual-, family-, and societal-level factors.50-52 This study found that subjects with symptoms had a lower level of psychological resilience than did subjects with no symptoms. This may be related to individual factors,47,53 including physical health, cognition and the efficacy of personal coping mechanisms. Another finding in our study was that compared to patients without fear of the COVID-19, patients with fear of the disease reported more severe symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, and distress. A study from Europe showed that productive sleep was associated with a lower risk of experiencing distress.54 As patients with COVID-19 are at an especially high risk of experiencing symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, and distress, their mental health and social support systems may require special attention.

Our research also has some limitations. First, compared with face-to-face interviews, self-reported data has certain limitations. Second, the study was cross-sectional and did not track the efficacy of psychological services. Because of changes in posttraumatic mental health, dynamic observation is necessary. A randomized prospective study could better determine the correlation and causation. Third, a larger sample size is needed to verify the results.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that the sleep quality, anxiety, and depression of COVID-19 patients in Fangcang shelter hospitals are significantly related to the impact of the epidemic. The mental research scales of COVID-19, including the levels of sleep quality, anxiety, depression, self-efficacy, stress, and social support, and the correlation between the levels of social support and the mental health of COVID-19 patients, also provide a set of tools for psychiatrists in clinical psychological assessment, testing and practice management for patients.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81630031), National Science and Technology Major Project for Investigational New Drug (2018ZX09201-014), Tianjin Municipal Science and Technology Project (No. 17ZXMFSY00100), and Extension project of the First Teaching Hospital of Tianjin University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (No. 2020004).

Conflicts of interest

None.

Acknowledgments

We thank Xue-Zheng Liu from the First Teaching Hospital of Tianjin University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, as well as Lei Zhang from Binhai New Area Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, for coordinating the data collection. We thank Gui-Feng Zhao from the First Teaching Hospital of Tianjin University of Traditional Chinese Medicine for assisting with data collection.