The Quality of Genetic Counseling and Connected Factors as Evaluated by Male BRCA1/2 Mutation Carriers in Finland

Abstract

There is little written about the quality of genetic counseling for men with the BRCA1/2 mutation. The purpose of this study was to describe the quality of genetic counseling and connected factors according to Finnish male BRCA1/2 mutation carriers’ (n = 35) perspectives and reasons for seeking genetic counseling. Data were collected from the Departments of Clinical Genetics at five Finnish university hospitals. The exploratory study design was conducted using a 51-item questionnaire based on a previously devised quality of counseling model and analyzed using non-parametric tests and principle content analysis. The satisfaction level with genetic counseling was high, especially with regard to the content of genetic counseling. The benefit of genetic counseling on the quality of life differed significantly (p < 0.001–0.009) from other factors. In particular, genetic counseling was in some cases associated to reduce the quality of life. Only 49 % of the male carriers felt they received sufficient counseling on social support. Attention to individual psychosocial support was proposed as an improvement to genetic counseling. Primary and secondary reasons for seeking genetic counseling and background information, such as education, affected the perceived quality of genetic counseling. The results of the study could be used to tailor genetic counseling for male BRCA1/2 mutation carriers.

Introduction

Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer may be caused by mutations in the BRCA1 (Miki et al. 1994) and BRCA2 genes (Wooster et al. 1995). BRCA1 and BRCA2 (BRCA1/2) mutation carrier females have a 40–80 % increased lifetime risk of breast cancer and 11–40 % risk of ovarian cancer. Male BRCA1/2 mutation carriers have an increased risk of developing prostate cancer by up to 30–39 % and a 1–10 % risk of male breast cancer (Petrucelli et al. 1998). BRCA1/2 mutations also increase the risk of other cancers, but the absolute risk is low (Levy-Lahad and Friedman 2007). Breast self-examination and prostate specific antigen (PSA) tests and digital rectal examination are recommended for male carriers aged 40 years and older. Mutation carriers’ offspring have a 50 % risk of inheriting the BRCA1/2 mutation. When a BRCA1/2 mutation is identified in a family, family members are offered genetic counseling and mutation testing to determine whether they are carriers. (Petrucelli et al. 1998). Previous studies have shown that the main reason for seeking genetic counseling by male carriers of BRCA1/2 mutations is to determine whether they have transmitted the mutation to their offspring (Lodder et al. 2001), especially their daughters (Liede et al. 2000; Daly et al. 2003). Reasons for testing also include following family recommendations (Liede et al. 2000), solidarity with other relatives (Daly et al. 2003) and learning their own personal risk of cancer (Liede et al. 2000; Daly et al. 2003).

Genetic counseling for cancer syndromes is largely a communication process, the goal of which is to give the individual comprehensible information on the familial cancer syndrome, medical facts, risks of developing cancer, the prospects for prevention and purpose of genetic testing via a counseling session delivered by a genetic health-care professional (Resta et al. 2006; EuroGentest 2008). Individual psychosocial evaluation and support should be offered and resources provided to facilitate counseling on genetic testing (EuroGentest 2008). Previous studies have shown that patients attending genetic counseling for hereditary cancer have been reported to be highly satisfied. Genetic counselors’ medical knowledge has been shown to be an important factor for patients’ satisfaction with genetic counseling (Bjorvatn et al. 2007). According to Liede et al. (2000), satisfaction levels with genetic counseling among male BRCA1/2 mutation carriers are also high. The studied men felt they received adequate information on their own condition and that of female relatives.

The quality of counseling can be defined in many ways and explored from various perspectives, such as that of health-care providers (Kyngäs et al. 2005), health-care professionals (Lipponen et al. 2006) and patients (Kaakinen et al. 2012a). In the present study, high quality of counseling is defined as being implemented with appropriate resources in an individual manner and having a sufficient and positive effect (Kääriäinen 2007; Kääriäinen and Kyngäs 2010; Kääriäinen et al. 2011). Counseling has been widely studied among chronically ill patients (Kaakinen et al. 2012b). According to Kaakinen et al. (2013), good quality of counseling is patient-centered and interactive between patients and counselors, providing, e.g., knowledge of disease symptoms, disease progression and social support, and has a positive effect on treatment and chronically ill patients’ attitudes.

Previous studies have examined patients’ expectations of and satisfaction with genetic counseling and reasons for seeking genetic counseling. Few of the studies focused on male BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. The growth in genetic testing for familial cancer syndromes and lack of sufficient and research-based knowledge on genetic counseling makes it important to develop high quality genetic counseling practices. Therefore further knowledge is needed. The purpose of this study was to describe the perceptions of the quality of genetic counseling by male BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. The main research questions were as follows: 1) What are the male carriers’ reasons for seeking genetic counseling? 2) What is the quality of genetic counseling like? 3) What factors are connected to the quality of genetic counseling?

Methods

Participants

The study employed an exploratory design based on a questionnaire administered through the Department of Clinical Genetics at five Finnish university hospitals. In these hospitals, genetic counseling is conducted by clinical geneticists or genetic nurses and the protocols of genetic counseling for hereditary cancer syndromes comply with recommendations for genetic counseling (EuroGentest 2008). The inclusion criteria were as follows 1) male, 2) fluent Finnish speakers, 3) person identified as BRCA1/2 mutation carriers after genetic counseling and testing, 4) persons who were known to be BRCA1/2 mutation carriers for no more than 4 years before data collection began. There were sixty-six (n = 66) eligible patients.

Procedure

The study period was from October to December 2013. The Departments of Clinical Genetics selected participants according to the above criteria and sent them an invitation letter, informed consent form and questionnaire. The questionnaires were returned to the fourth author (H.K.) by post mail. Out of the 66 eligible patients approached, only 30 questionnaires were returned. Thus, the data collection was repeated because of the initial low response rate. After the second data collection campaign, the total number of returned questionnaires increased to 36, and therefore the final response rate was 55 %. One questionnaire was eliminated because it was received after data analysis had started.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire used in this study was based on the quality of counseling model devised by Kääriäinen (2007), whose Counseling Quality Instrument (84 items) covers the areas: resources, content, implementation and benefit of counseling. The questionnaire used in this study was modified by adding a question concerning the male carrier's reasons for seeking genetic counseling based on the findings of previous studies (Liede et al. 2000; Lodder et al. 2001; Daly et al. 2003; Hallowell et al. 2005, 2006) and literature. The demographic data and questions concerning the quality of counseling also were modified to be suitable for the study; e.g., questions concerning fluid balance and medication were deleted. The content validity of the questionnaire (59 items) was evaluated by two nursing science experts and seven genetic nursing experts. Following their feedback, six items were deleted; resources (3 items), content (1 item) and implementation of genetic counseling (2 items) and one item added; benefit of genetic counseling (1 item). The concept was also changed and clarified to be more congruent. After these modifications, the questionnaires (54 items) content validity was reassessed by a panel of four experts of genetic nursing according to a four-point scale of relevance (1 not relevance – 4 highly relevance). Based on the latter evaluation, five items were deleted; resources (1 item), content (1 item), implementation (2 items), benefit of genetic counseling (1 item) and two items added; implementation of genetic counseling (2 items) and contents of two items were changed; implementation (1 item) and benefit of genetic counseling (1 item) and the numbering of the questionnaire was changed to be chronological. The questionnaire was subsequently pretested on part of the same kind of population as in the main study, i.e., men identified as BRCA1/2 mutation carriers up to 4 years prior to pretesting (n = 14) at one department of clinical genetics involved in the main study. The pretesting recruitment and questionnaire's return were carried out using the same procedure as in the main study. The men were asked to respond to the questionnaire and also give opinions about the questionnaire, instructions and questionnaire's appearance. Six questionnaires were returned, none were rejected. As a result of the pretesting, instruction to one of the questions was clarified after the pretesting. The pretest participants were not included in the sample of main study.

The final version of the questionnaire consisted of 51 items, i.e., 1) demographic data including age, marital status, level of education, number and gender of offspring and siblings, time confirmed as a BRCA1/2 mutation carrier, mutation status, cancer status and a question concerning surveillance recommendations, 2) primary and secondary reasons for seeking genetic counseling, and 3) quality indicators of genetic counseling. The quality of genetic counseling consisted of four areas, i.e., resources of genetic counseling (4 items), content of genetic counseling (7 items), implementation of genetic counseling (20 items) and benefit of genetic counseling (7 items). Responses were given according to a four-point (1 strong disagreement – 4 strong agreement) Likert scale. The men were also asked to evaluate counseling overall on a five-point (1 poor – 5 excellent) Likert scale. There was one open-ended question, which asked participants to propose ways for improving genetic counseling.

Ethical Issues

The participants received the invitation letter and informed consent forms from their local Department of Clinical Genetics. The researchers were not involved in the recruitment of participants. Participation in the study was voluntary. The participants returned the informed consent form and questionnaire to the fourth author. The participants were not identified. The researcher received anonymous questionnaires after codifying by the fourth author. Anonymity was protected throughout the research process. The study was approved by the official Research Ethics committee of the Northern Ostrobothnia Hospital District (60/2013 133§) and separate research permission to conduct the study was obtained from the individual Departments of Clinical Genetics according to their local practice.

Data Analysis

The data were analyzed statistically using IBM SPSS Statistics 22.0. Part of the background data was classified into new categories. Age was divided into two classes (<40 and ≥40 years) according to the age when the surveillance of BRCA1/2 male carriers should be started. Marital status was classified as in a relationship and or not in a relationship. The time identified as a carrier was as divided into two classes (≤2 and >2 years), whereas educational level was categorized as non-occupational, occupational or university education. The response alternatives for the primary and secondary reasons for seeking genetic counseling within the aforementioned contents categories were as follows: 1) personal reasons, e.g., to gain knowledge of own personal risk of cancer and BRCA1/2 mutations; 2) offspring reasons, e.g., to find out if the mutation could be transmitted to their offspring and how their offspring could obtain genetic testing and surveillance if needed, and 3) other relatives’ reasons, e.g., solidarity with or responsibility for other relatives.

Six sum variables were constructed from the items that measured the quality of genetic counseling. Statistical information of sum variables is presented in Table 1. The area resources of genetic counseling: the sum variable entitled resources of genetic counseling consisted of space, time and informant's knowledge. For example, one question was “The genetic counseling was executed in suitable space”. The area content of genetic counseling: the content of genetic counseling included the meaning of the genetic test result to the participant and their offspring and content of counseling. The content of counseling included awareness of the BRCA1/2 mutation (e.g., inheritance), men's own risk of cancer and cancer risk of their female relatives. Questions outside the sum variable of the content of genetic counseling concerned the social support, such as “You received sufficient counseling on mental well-being related issues”, and the securing of necessary contacts defined as where or who they could get in touch in case of questions. The area implementation of genetic counseling focused on the patient-centered genetic counseling. Examples of the questions were “Your spouse/partner was included in the counseling situation if you wanted” and “You were allowed to ask questions.” Out of the sum variable were questions of confidentiality, peacefulness of the counseling situation and intelligibility of the presentation. The area benefit of genetic counseling was divided into the benefit on the quality of life and benefit on knowledge of BRCA1/2 mutation. The benefit on the quality of life concerned the ability to function, health, sentiment and attitude to life. The benefit on knowledge of BRCA1/2 mutation included questions of effects on knowledge and understanding towards BRCA1/2 mutation. Internal consistency was assessed by Cronbach's alpha (α). Five items were not included in the sum variables. The sum variables were divided into two classes, i.e., those with a score of 1.00–2.49 (poor) and 2.50–4.00 (good) (Table 2).

| Sum variable | na | Meanb | SDc | Min | Max | αd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resources of genetic counseling | 4 | 3.78 | 0.39 | 2.25 | 4.00 | 0.67 |

| Content of genetic counseling | ||||||

| Content of counseling | 3 | 3.69 | 0.44 | 2.50 | 4.00 | 0.65 |

| Meaning of genetic test result | 2 | 3.73 | 0.53 | 1.50 | 4.00 | 0.77 |

| Implementation of genetic counseling | ||||||

| Patient-centered genetic counseling | 17 | 3.55 | 0.46 | 2.31 | 4.00 | 0.89 |

| Benefit of genetic counseling | ||||||

| Benefit on quality of life | 4 | 2.66 | 0.69 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 0.88 |

| Benefit on knowledge of BRCA1/2 mutation | 3 | 3.52 | 0.52 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 0.75 |

- aNumber of items bRange 1–4 cStandard deviation dCronbach's alpha

| Sum variable | Category rangea | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Resources of genetic counseling | 1.00–2.49 | Poor |

| 2.50–4.00 | Good | |

| Content of genetic counseling | ||

| Content of counseling | 1.00–2.49 | Non-sufficient |

| 2.50–4.00 | Sufficient | |

| Meaning of genetic test result | 1.00–2.49 | Non-sufficient |

| 2.50–4.00 | Sufficient | |

| Implementation | ||

| Patient-centered genetic counseling | 1.00–2.49 | Poor |

| 2.50–4.00 | Good | |

| Benefit of genetic counseling | ||

| Benefit on quality of life | 1.00–2.49 | Negative effect |

| 2.50–4.00 | Positive effect | |

| Benefit on knowledge of BRCA1/2 mutation | 1.00–2.49 | Negative effect |

| 2.50–4.00 | Positive effect | |

- aRange 1–4

Descriptive statistics was used to analyze the quality of genetic counseling. Non-parametric tests were used because some variables did not exhibit a normal distribution. Differences between background variables and sum variables were studied using pairwise comparisons estimated by Friedman's test and the Kruskall-Wallis test. Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (ρ) was used to analyze the strength and direction of associations between two variables and the sum variables. A p-value <0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. Only statistically significant results were reported. Answers to open-ended questions were categorized by using principle content analysis.

Results

Characteristics of the Participants

Table 3 shows the background information of the participants. The majority of the participants (86 %; 30/35) were aged ≥40, with a mean age of 55 years (SD = 13, range 29–80). Fifty-seven percent (20/35) were BRCA2 mutation carriers and 29 % (10/35) carried a BRCA1 mutation. Fourteen percent (5/35) did not remember in which BRCA gene they had a mutation. Sixty-four percent (21/33) of participants had received their genetic test results ≤2 years before the study and 36 % (12/33) over 2 years before (mean 29 months, SD = 30, range 2–161 months). Eighty percent (4/5) of the men who did not remember their mutation had received test results ≤2 years prior to the study. The majority of participants (79 %; 27/34) had been given surveillance recommendations after being identified as BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. Sixty-eight percent (17/25) of the men had complied with the instructions, the majority (94 %; 16/17) of which were aged ≥40 years. Eighty percent (4/5) of the men without occupational education, 69 % (11/16) of men with occupational education and 50 % (2/4) of men with university education had followed the instructions. Sixty-three percent (5/8) of the men who did not agree with the surveillance recommendations were BRCA2 mutation carriers. Of the men who had not received surveillance recommendations, non had attended spontaneous surveillance. Six men had been diagnosed with cancer prior to entering genetic counseling. Two of those men had two or more cancers, i.e., breast (n = 2), colon (n = 3) and prostate cancer (n = 2). Other cancers were also reported, such as skin cancer (n = 2).

| Characteristics of participants (n = 35) | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | ||

| < 40 | 5 | 14 |

| ≥ 40 | 30 | 86 |

| Marital status | ||

| In a relationship | 33 | 94 |

| Not in a relationship | 2 | 6 |

| Educational level | ||

| Non-occupational education | 7 | 20 |

| Occupational education | 20 | 57 |

| University education | 8 | 23 |

| Offspring | 31 | 89 |

| Siblings | 33 | 94 |

| Diagnosed with cancer | 6 | 17 |

Reasons for Seeking Genetic Counseling

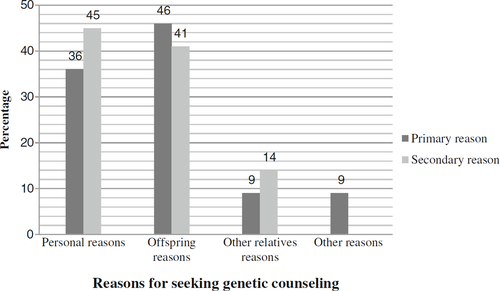

Primary and secondary reasons for seeking genetic counseling are presented in Fig. 1. Another primary reason for seeking genetic counseling was concern over offspring contracting cancer. The men with university education stated personal reasons were the primary (75 %; 6/8) or secondary reason (71 %; 5/7) for seeking genetic counseling. Offspring reasons were reported as the primary reason by 57 % (4/7) of the men without occupational education and 56 % (10/18) of the men with occupational education. In contrast, offspring reasons were considered secondary reasons by 80 % (4/5) of men with non-occupational education. Secondary reasons comprised personal and offspring reasons (41 %; 7/17) by men with occupational education.

Primary and secondary reasons for seeking genetic counseling

Quality of Genetic Counseling

Overall, satisfaction with the genetic counseling was scored as excellent (mean 4.46, range 2–5). Over half of the men (57 %; 20/35) evaluated the genetic counseling as excellent, 34 % (12/35) evaluated as good, 6 % (2/35) as acceptable and 3 % (1/35) as tolerable. None of the men evaluated the counseling as poor. The resources of genetic counseling were good according to most men (97 %; 34/35). All men considered that the content of genetic counseling was sufficient. Most men (97 %; 34/35) evaluated that they received sufficient counseling on the meaning of genetic test results and over half (54 %; 19/35) of the men had received sufficient information about contacts. Social support was rated as sufficient by 49 % (17/35) of the men. The implementation of patient-centered genetic counseling was considered good according to 91 % (32/35) of the men, although only 58 % (19/33) of men felt that their spouse/partner was fully included. Five of the men felt that their spouse/partner was not included at all. All of these men were living in a relationship. Most of the men (97 %; 34/35) believed that the genetic counseling was conducted in a confidential manner and in peaceful environment. The benefit of the genetic counseling on the quality of life was viewed as positive by 62 % (21/34) and negative by 38 % (13/34) of the men, whereas the benefit on knowledge of BRCA1/2 mutation was deemed positive by 97 % (34/35) of the men.

According to Friedman's test, the genetic counseling's benefit on the quality of life differed significantly from other factors, i.e., effect of resources of genetic counseling (p < 0.001), content of counseling (p < 0.001), meaning of genetic test results (p < 0.001), benefit on knowledge of BRCA1/2 mutation (p = 0.001) and implementation of patient-centered genetic counseling (p = 0.009).

The men provided recommendations for improving genetic counseling. Many of the men wished for an opportunity to have a second counseling session after being identified as BRCA1/2 mutation carriers, either as a visit to a clinic or telephone call. In addition, they felt that it would be useful to rerun counseling after life situation changes, e.g., when starting a family. Many men hoped that surveillance follow-ups would be arranged automatically and their continuance would be guaranteed. It was also proposed that men's individual support should be perceived and psychological support should be offered from a psychology professional. Many of the men expressed a wish to share information with offspring and relatives.

Factors Connected with the Quality of Genetic Counseling

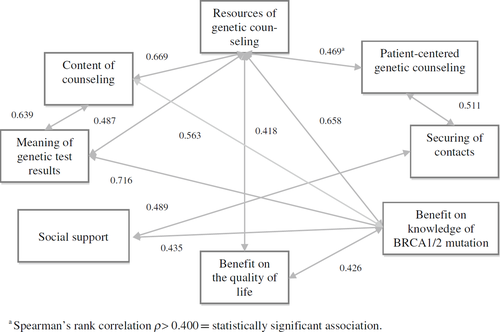

There was a statistically significant association between different variables of the genetic counseling (Fig. 2). The resources of genetic counseling correlated with how sufficiently BRCA1/2 mutation carrier men had received counseling on the meaning of genetic test results for themselves and their offspring (p = 0.003) and how sufficient the content of counseling was (p < 0.001), with the realization of patient-centered genetic counseling (p = 0.004) and how men evaluated the genetic counseling's benefits on their quality of life (p = 0.014) and knowledge of BRCA1/2 mutation (p < 0.001). Sufficiency of content of the genetic counseling was significantly associated with how sufficiently men received information on the meaning of genetic test results (p < 0.001) and the benefit on knowledge of BRCA1/2 mutation (p < 0.001). The meaning of genetic test results (p < 0.001), sufficiency of social support (p = 0.009) and genetic counseling's benefit on the quality of life (p = 0.012) were associated with the benefit on knowledge of BRCA1/2 mutation. The sufficiency of securing contacts was associated with the implementation of patient-centered genetic counseling (p = 0.002) and sufficiency of social support (p = 0.003). According to Friedman's pairwise comparison test, the patient-centered genetic counseling departed significantly from the resources of genetic counseling (p = 0.018).

Factor associations to strength and direction

The men with a university education evaluated resources as better in the pairwise comparisons than men with an occupational education (p = 0.037). The men with offspring also evaluated resources as better than men without offspring (p = 0.029). The men who had been identified as BRCA1/2 mutation carriers ≤2 years before data collection were more pleased with implementation of patient-centered genetic counseling than men who had received their genetic test result >2 years (p = 0.035) ago. Men aged ≥ 40 years felt the genetic counseling was conducted in a peaceful setting (p = 0.016) and they received sufficient counseling on the meaning of genetic results for themselves and their offspring (p = 0.010). The men who had a diagnosed cancer evaluated benefit on knowledge of BRCA1/2 mutation as better than others (p = 0.032). According to most men (94 %; 33/35), understandable language was used and the intelligibility of the language was evaluated as highest by the men who had siblings (p = 0.005) or received surveillance recommendations (p = 0.005). In addition, the men who received surveillance recommendations were satisfied with the information given on contacts (p = 0.015).

Men whose primary reason for seeking genetic counseling was other than personal or offspring reasons rated the environment of genetic counseling more peaceful than men who had personal (p = 0.023) or offspring reasons (p = 0.017). Men whose secondary reason for seeking genetic counseling was other relative reasons evaluated the resources (p = 0.013), sufficiency of content of counseling (p = 0.040) and benefit on knowledge of BRCA1/2 mutation (p = 0.030) better than men whose secondary reason was personal reasons. The former men also evaluated resources (p = 0.013) better than the men who gave offspring reasons as a secondary reason.

Discussion

For almost half (46 %; 15/33) of the BRCA1/2 mutation carrier men of this study the primary reason for seeking genetic counseling was for offspring reasons, whereas 41 % (12/29) of the men stated that these were a secondary reason. Personal reasons, so as to receive information on cancer risk, were the primary reason for 36 % (12/33) of the men and a secondary reason for almost half (45 %; 13/29) of the men. These results are similar to the findings of other studies (Daly et al. 2003; Hallowell et al. 2005). However, in the present study, other relative reasons, such as solidarity towards other relatives, had a more minor role than others. It was interesting that men's educational level seemed to affect their reasons for seeking genetic counseling, e.g., the primary and secondary reason of the most highly educated men was clearly personal reasons. In contrast, men without occupational education mainly sought counseling for offspring reasons. The reasons for seeking genetic counseling were connected to the benefit on knowledge of BRCA1/2 mutation. In addition, background data were connected to men's evaluation of quality of the genetic counseling. Lobb et al. (2002) showed that patient demographics are a significant predictor of clinical geneticists’/genetic counselors’ communication behavior toward women from high risk breast cancer families. This might be consistent with the men's evaluation in present study.

The satisfaction level with genetic counseling was excellent. The men evaluated content of genetic counseling to be sufficient, this is in line with an earlier study (Liede et al. 2000), which showed that most of male carriers received adequate information on e.g., surveillance practices, prevention of cancer and their females’ relatives about risk of development of cancer. Based on Kaakinen et al. (2012a) the most chronically ill patients received sufficient patient counseling on disease symptoms and results of the investigations, but less than half of the patients received patient-centered counseling. In the present study the patient-centered genetic counseling was taken into account well, except with regard to the inclusion of men's spouse/partner during the counseling and men did not receive sufficient counseling on who to contact if they had questions.

The results of the study indicate that the quality of genetic counseling was considered good in almost all areas. Only the benefit of genetic counseling on the quality of life differed from other quality factors. Almost half of the men (38 %; 13/34) reported that genetic counseling had decreased their quality of life. Braithwaite et al. (2006) showed in a meta-analysis that genetic counseling for familial cancer did not have an adverse psychological impact such as depression or distress. Fantini-Hauwel et al. (2011) reported variable results: some participants showed higher anxiety levels and some lower after genetic testing for hereditary cancer. In studies on BRCA1/2 carrier males, it was reported that positive test results can increase distress (Shiloh et al. 2013) and cause strong emotional reactions (Strømsvik et al. 2010).

It is alarming that only about half (49 %; 17/35) of the men in the present study felt they received enough counseling for social support, which is consistent with previous findings for chronically ill patients (Kaakinen et al. 2012a). On the whole, in this study, the men were satisfied with the genetic counseling they received. They also suggested good ideas for developing the counseling, which were partly connected to results on the insufficiency of social support. Many of the men believed that further counseling and follow-ups were important. The men's reported need for individual psychosocial support and information packages were similar to the findings of Mendes et al. (2011) concerning the experiences of genetic counseling by patients with hereditary cancer.

Study Limitations

The major limitation of this study was the small sample size. It is common in survey studies that the response rate is low. Therefore, to alleviate this limitation, data collection was organized via the Departments of Clinical Genetics of all university hospitals in Finland. Low participation rates have also been reported in previous studies concerning male BRCA1/2 mutation carriers (Strømsvik et al. 2009, 2010). Given the exploratory nature of this study, we conducted a number of univariate test with a p-value on 0.05. Although this approach is acceptable for an exploratory study, it is possible that some of the findings are significant by chance. Regardless of the limitations of sample size, the questionnaire's validity and reliability have been rated high in previous studies (Kääriäinen 2007; Kääriäinen and Kyngäs 2010; Kääriäinen et al. 2011). The questionnaire has been used in several previous studies, e.g., in a study of the quality of counseling of chronically ill patients (Kaakinen et al. 2012a, 2013). The questionnaire was modified for application in the present study and the content validity was assured by experts. The content validity index (S-CVI) of the questionnaire was 0.96, which is rated as excellent (Polit and Beck 2006). Furthermore, the questionnaire was pretested. The Cronbach alpha values showed high internal consistency: the Cronbach alpha value for the whole questionnaire was 0.90 and the range for the sum variables was 0.65–0.89.

The validity of this study is supported by the fact that the genetic counseling was conducted by clinical geneticists or genetic nurses according to the same protocol at each of the Departments of Clinical Genetics. A minor limitation of the study was that environment of genetic counseling was not necessarily identical for all study participants. Another limitation of the study is that three of the men had received their genetic test result over 4 years before data collection. The mean time since test results were received was 2.4 years, which is consistent with previous studies, where BRCA1/2 mutation carrier men evaluated experiences with genetic counseling (Liede et al. 2000) and impacts of genetic test result (Shiloh et al. 2013). In principle, these periods could have affected their recall of the details of genetic counseling or motivation for seeking genetic counseling. However, there was only one statistically significant connection between men's evaluation of the quality of genetic counseling and when they received their test result: connection concerning implementation of patient-centered genetic counseling.

In the present study, researchers were not involved in the selection of men for the study. Details on men's mutation details and time when they received the genetic test result or surveillance recommendations were not checked against a register of patients, as all data were self-reported by the participants.

Practice Implications

The results of this study have implications for clinical practice. Particular attention should be paid to the resources required for genetic counseling, like providing enough time and space. Health-care professionals should have adequate training and knowledge to provide personal genetic counseling and information in the way patients understand. By paying attention to demographic information and motivations for seeking counseling, genetic counseling could be tailored toward the individual needs of the patients. In particular, the need for psychosocial support during the counseling process should be recognized and assessed. Men should be given the opportunity to be accompanied by their spouses during counseling and they should be aware of who to contact if further questions arise.

Research Recommendations

Further research is needed to improve the quality of genetic counseling. The subject should be addressed by qualitative research, especially by studying the effect on the quality of life of men identified as BRCA1/2 mutation carriers and what kind of psychosocial support male BRCA1/2 mutation carriers are looking for. To improve genetic counseling, it would also be useful to study the experiences of BRCA1/2 carrier men as mutation carriers. In previous studies, it has been reported that carrier men have emotional reactions (Strømsvik et al. 2010) and fear of developing cancer (Strømsvik et al. 2011). The results of the present study can be exploited as themes for further study. Once the quality of genetic counseling has been studied by quantitative and qualitative methods, it would be useful to study the quality in other populations.

Conclusions

The quality of genetic counseling was evaluated as good by Finnish male BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. The resources and content of genetic counseling have a key role on the quality of genetic counseling. The results of this study show that genetic counseling can in some cases reduce the quality of life of male BRCA1/2 carriers. Further, social support should be paid more attention in genetic counseling.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Drs Kristiina Aittomäki, Jaakko Ignatius, Tarja Mononen, Kalle Simola and the assistants at the Departments of Clinical Genetics at the participating university hospitals for helpful discussions and data collection. We thank genetic nurses at the Departments of Clinical Genetics for sharing their expertise in the instrument developing process. M.Sc. Helena Laukkala is thanked for statistical analysis guidance. We also thank all male carriers who participated in this study. This study was partly supported by the Department of Clinical Genetics at Oulu University Hospital (Genetic Diseases in Northern Finland research group).

Conflict of Interest

Outi Kajula, Maria Kääriäinen, Jukka S. Moilanen and Helvi Kyngäs declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human Studies and Informed Consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Animal Studies

No Animal studies were carried out by the authors for this article.