Beger's operation and the Berne modification: origin and current results

Abstract

Background/purpose

The purpose of this paper is to illuminate the origin and current results of the duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection (DPPHR) developed by Beger in the 1970s, as well as its simplified Berne modification, for patients suffering from chronic pancreatitis (CP). Indications for the procedures and their results are presented on the basis of available data.

Methods

A selected review was made of the available data on the DPPHR developed by Beger and its modifications.

Results

The organ-sparing DPPHR developed by Beger, and its modifications, provide better pain relief, better preservation of exocrine and endocrine pancreatic function, and a superior quality of life compared with the more radical pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD, with or without pylorus-preservation), once the standard treatment for patients with CP. Recently published data on the long-term follow-up of studies comparing PD to DPPHR indicate that the initial benefits of DPPHR over PD might be less pronounced in the long-run.

Conclusions

The organ-preserving DPPHR developed by Beger, and its modifications, have become established and well-evaluated surgical treatment options for patients with CP.

Introduction

Chronic pancreatitis (CP) is a benign inflammatory disease of the pancreas that leads to irreversible damage of functional parenchyma and disruption of exocrine and endocrine function, ultimately resulting in gland atrophy with or without calcifications 1-3. The incidence and prevalence of CP seems to be country-specific, with higher rates having been reported in Japan (incidence, 14.4 per 100,000 inhabitants; prevalence, 35.5 per 100,000 in 2002) [4] than in European countries 5-7. Interestingly, in Japan, incidence and prevalence rates have shown a marked increase over time [8].

Although the pathogenesis of CP is not yet fully understood, etiologic factors for CP have been well-established and are commonly summarized using the TI-GAR-O classification [9]: toxic-metabolic (e.g. alcohol), idiopathic, genetic, autoimmune, recurrent and severe acute pancreatitis or obstructive (e.g. pancreas divisum or pancreatic neoplasm). In industrialized countries, over-consumption of alcohol is the leading cause of CP, accounting for 65–90% of all cases [4, 6, 7].

Clinical presentation and indications for surgery

The predominant clinical symptom in patients with CP is pain, which affects more than 90% of patients [10]. Other common symptoms are diabetes mellitus and steatorrhea, due to endocrine and exocrine insufficiency of the gland, respectively [10]. While the latter symptoms can be treated medically, intractable pain is the leading indication for surgery in patients with CP, with 50% of patients suffering from pain after 15 years despite medical treatment 10-12. Although pain in patients with CP and pancreatic duct stenosis can be treated by endoscopic procedures, which offer success in approximately 65% of patients [13], two randomized prospective studies have shown the superiority of surgery over endotherapy [14, 15].

Other indications that warrant surgery in CP arise from local complications. CP is most frequently localized in the pancreatic head, and an inflammatory pseudotumor may lead to the compression of neighboring organs, causing symptomatic duodenal and common bile duct obstruction, as well as vascular obstruction of the portal, superior mesenteric, and splenic veins. All of these may warrant surgery, especially if more than one complication is present at once. Pancreatic pseudocysts may be another indication for surgery, although endoscopic drainage procedures are effective in this situation as well. Finally, suspicion of a pancreatic malignancy warrants surgery, since CP is an independent risk factor for the development of pancreatic cancer 16-18.

Surgical treatment options for CP

Two types of surgical interventions have been proposed and carried out in patients with CP: drainage and resection procedures. Mere drainage operations, most commonly the Partington–Rochelle procedure, [19] in which a lateral pancreaticojejunostomy is constructed with a Roux-Y jejunal loop, have been successfully used to treat pain in patients with dilated pancreatic duct CP (large-duct CP) 20-22. Although there is no universally accepted definition of large-duct CP, most authors classify large-duct CP as that having a pancreatic duct diameter of more than 6–7 mm 23-25. The presence of a dilated pancreatic duct, however, is not the only prerequisite for a drainage operation, the other being the absence of local obstructive symptoms (such as common bile duct or duodenal obstruction), which are not addressed by drainage operations. Therefore, only about 25% of all CP patients qualify for a drainage operation in the first place [26]. Furthermore, while drainage operations are efficient and safe procedures, conferring short-term pain relief in approximately 80% of patients [20, 22, 27], series with long-term follow up have yielded disappointing results, with approximately 40% of patients complaining of pain 2 years after surgery [21, 28, 29], most likely due to a progression of the chronic inflammation in the remaining pancreatic tissue. This seems understandable, given that pain in CP seems to be a multifactorial event involving neuro-immunological interactions 30-33, inflammation, and increased intraductal/intraparenchymal pressure [34] and thus may not be effectively treated by mere drainage of the pancreatic duct system.

Many of the drawbacks of the drainage operation are addressed by resection procedures. Resection procedures remove the inflammatory mass in the pancreatic head found in approximately half of all CP patients and believed to be the pacemaker of CP [35, 36], thereby alleviating local compression symptoms, as well as achieving pain relief. Furthermore, resection procedures can be used in small-duct CP 23-25 and relieve common bile duct stenosis, which is present in 40–50% of patients [36]. The classical resection procedures for the pancreatic head are the Kausch–Whipple pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) [37, 38] and its pylorus-preserving counterpart described by Traverso and Longmire (ppPD) [39].

PD has served as the primary surgical procedure for the treatment of CP since its introduction, as it is associated with long-term pain relief in a majority of patients and can be carried out with low mortality rates, especially at high-volume centers 40-43. However, PD is associated with poor long-term results in patients with CP, and postoperative and overall morbidity remains high [40, 44-47]. Introduction of the pylorus-preserving PD (ppPD) yielded mixed results as to the benefits it might bring in comparison to the classic PD 48-51. A recent meta-analysis of 7 randomized controlled trials (RCT) including a total of 496 patients found no difference between the two procedures concerning in-hospital mortality, overall survival, and overall morbidity [52]. These studies, however, were carried out in patients suffering from pancreatic cancer, and no RCT exist comparing PD with ppPD in patients with CP. However, Jimenez et al. report a retrospective trial (level IIb evidence) of 72 patients undergoing PD or ppPD for CP, showing comparable rates of long-term pain relief, nutritional status, diabetes mellitus, and enzyme supplementation [42]. Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) with or without pylorus-preservation has remained the standard treatment option at many centers across the United States [53], may be due to unaccounted differences between CP patients in different countries [54]. Both procedures, however, were originally developed to treat malignant diseases of the pancreatic head and the periampullary region, whereas CP is a benign disorder of the pancreas that does not necessarily warrant radical surgical approaches.

Beger's duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection

In order to improve the long-term outcome in patients with CP and to limit the resection of pancreatic tissue to a minimum, the duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection (DPPHR) was introduced by Beger and colleagues [55, 56] in the 1970s. The rationale for this surgical procedure is to remove the inflammatory mass in the pancreatic head, thereby achieving sufficient bile and pancreatic drainage and decompression of the duodenum and the neighboring vasculature, as well as removal of the inflammatory substrate causing pain. At the same time the duodenum is preserved to allow physiologic food passage and hormonal secretion. Beger's DPPHR is a less traumatic surgical procedure than the more extensive PD or ppPD and is specifically tailored to CP.

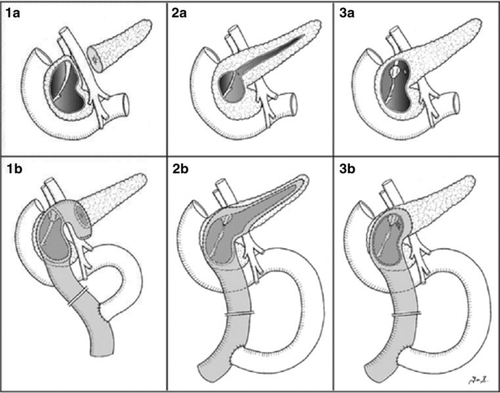

In Beger's operation the pancreatic head and body are exposed in their entirety by division of the gastrocolic ligament and caudal mobilization of the hepatic colon flexure, followed by a Kocher maneuver. The right gastroepiploic vessels are divided to give full exposure of the pancreas as well as the superior mesenteric and portal veins. In the next step the pancreas is divided above the portal vein and the inflammatory mass is removed from the pancreatic head, leaving a 5- to 8-mm rim of tissue adjacent to the duodenal wall (Fig. 1(1a)). Reconstruction is achieved by means of a Roux-Y jejunal loop with an end-to-side anastomosis to the pancreatic body and a side-to-side anastomosis to the excavated pancreatic head (Fig. 1(1b)). In cases of a fixed bile duct stricture that is not released by removal of the surrounding pancreatic parenchyma, the bile duct can be incised and integrated into the pancreatic head anastomosis.

Berne modification of Beger's operation

The technically demanding Beger's operation has undergone several modifications. One of these is the Frey's operation, in which a limited excavation of the pancreatic head is combined with a longitudinal pancreaticojejunostomy (Fig. 1(2a, b)) [57, 58]. In this variant, the dissection of the pancreas from the portal vein and the transection of the pancreas are not necessary. This is especially noteworthy, as this step can be time-consuming and complication-prone as patients with CP may exhibit inflammatory portal vein encasement and portal hypertension.

The Berne modification (Berne DPPR), developed in the 1990s, [59] aims to combine the advantages of Beger's and Frey's operations. Contrary to Beger's DPPHR, the pancreas is not transected in the Berne modification, but rather, the anterior capsule of the pancreatic head is incised and the enlarged inflammatory mass is removed almost in its entirety, leaving only a thin rim of pancreatic tissue (Fig. 1(3a)). In this way a continuous cave consisting of the dorsal capsule and a small bridge of pancreatic tissue remains that is then incorporated into a single side-to-side anastomosis with an interposed Roux-Y jejunal loop (Fig. 1(3b)). The common bile duct is frequently incised and included in the pancreatic anastomosis to ensure adequate biliary drainage. As with Beger's operation, the pancreatic duct should be explored intraoperatively and if stenoses are present distally, it can be incised in the body and tail region and anastomosed to the jejunal loop, as was proposed by Frey.

Outcome of Beger's operation

Beger's DPPHR has become a well-established and thoroughly analyzed surgical procedure. Several studies have established that Beger's DPPHR is a safe operation, with mortality rates ranging between 0 and 2%, and morbidity rates ranging between 15 and 54% 60-63. Furthermore, long-term pain relief is achieved in approximately 80% of patients at 5-year follow up, with a low long-term endocrine insufficiency rate 60-63. In addition, in terms of quality of life (QOL), 69% of patients were professionally rehabilitated after DPPHR, and in 72% of patients the Karnofsky index was between 90 and 100% [61]. Given the natural cause of CP, with mortality rates ranging from 20 to 35% over an observation time of 6.3–9.8 years, [10, 64] the death rate after DPPHR compares favorably with these numbers, ranging between 8.9 and 12.6% in series with a follow up of more than 5 years [61, 63].

Comparison of Beger's operation with PD/ppPD

Two RCT have been performed comparing Beger's operation with pancreaticoduodenectomies (PD or ppPD) [40, 62] (Table 1). In the study by Klempa et al. [40] 43 patients were randomized to either undergo Beger's operation (22 patients) or PD (21 patients) for CP. After a follow-up period of 3.5 to 5 years, comparable numbers of patients were completely pain free in the two groups (70% DPPHR vs. 60% PD). However, the mean hospital stay was significantly shorter (16.5 vs. 21.7 days), exocrine insufficiency occurred significantly less often (10 vs. 100%), and postoperative weight gain occurred significantly more often in patients in the DHPPR group than in the PD group (80 vs. 30%). Similar results were reported in a RCT by Büchler et al. [62] comparing Beger's DPPHR (20 patients) to ppPD (20 patients). The mean follow-up period, however, was shorter than that in the study by Klempa et al. [40] (only 6 months). In this study there was a clear trend towards superior pain relief in the DPPHR group compared to the ppPD group (75 vs. 40%). Furthermore, although no significant differences in the frequency of weight gain (DPPHR 88% vs. ppPD 67%) were reported, the average weight gain in the DPPHR group was significantly higher than that in the ppPD group (4.1 ± 0.9 vs. 1.9 ± 1.2 kg). In addition, the endocrine function seemed to be better preserved in the DPPHR group, since after 6 months pathologic glucose tolerance was apparent in the ppPD group (mean, 130 mg/dl after 150 min) compared to 88 mg/dl in the DPPHR group. A third RCT comparing ppPD to Beger's DPPHR, performed by Makowiec et al., has not yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal [65]. Preliminary data, however, show a reduced operation time in the DPPHR group (368 vs. 435 min), but the data have failed to show any differences in QOL between the two groups. Contrary to this study, a nonrandomized controlled trial by Witzigmann, comparing Beger's DPPHR to PD, reported better outcomes in the DPPHR group [44, 45]. A long-term (5 year) follow up of this study confirmed the superiority of Beger's DPPHR over the classical Whipple operation in terms of QOL and pain intensity [66].

| Study (ref. no.) | Year | Design | Comparison | n | Overall postoperative morbidity, DGE, fistula, hemorrhage | Mortality | Blood Replacement (units), OR time, hospital stay in days (range) | Complete pain relief | Weight gain, average weight gain (kg) | New-onset DM exocrine insufficiency | Quality of life Mean Global health status on EORTC-QLQ-30 (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Klempa et al. [40] | 1995 | RCT (Ib) | PD | 21 | 12 (57%) | 0 (0%) | 2.7 | 12 of 20 (60%) | 6/20 (30%) | 6/16 (38%) | NA |

| 2 (9.5%) | NA | 4.9 ± 5.3 | 20 (100%) | ||||||||

| 1 (4.8%) | 21.7 (16–36) | ||||||||||

| 2 (9.5%) | |||||||||||

| DPPHR (Beger) | 22 | 14 (63%) | 1 (5%) | 2.5 | 14 of 20 (70%) | 16/20 (80%) | 2/17 (12%) | NA | |||

| 2 (9.1%) | NA | 6.4 ± 6.9 | 2 (10%) | ||||||||

| 0 | 16.5 (13–22) | ||||||||||

| 1 (4.5%) | |||||||||||

| Büchler et al. [62] | 1995 | RCT (Ib) | ppPD | 20 | 4 (20%) | 0 | 2.15 | 6 of 15 (40%) | 10/15 (67%) | NA | NA |

| NA | NA | 1.9 ± 1.2 | |||||||||

| 1 (5%) | 14 (9–37) | ||||||||||

| 0 | |||||||||||

| DPPHR (Beger) | 20 | 3 (15%) | 0 | 1.44 | 12 of 16 (75%) | 14/16 (88%) | NA | NA | |||

| NA | NA | 4.1 ± 0.9 | |||||||||

| 0 | 13 (8–21) | ||||||||||

| 2 (10%) | |||||||||||

| Müller et al. [67] | 2008 | RCT (Ib) | ppPD | 14 (5 dead, 1 lost to F/U) | See above | 5/19 (26.3%) | See above | No difference | NA | 6/9 | 58.3 (34.2) |

| Long-term F/U of Büchler triala | DPPHR (Beger) | 15 (5 dead) | See above | 5/20 (25%) | See above | NA | 4/11 | 65 (22.3) | |||

| Farkas et al. [74] | 2006 | RCT (Ib) | ppPD | 20 | 8 (40%) | 0 | 2.1 | 18 (90%) | 6 (30%) | NA | NA |

| 6 (30%) | 278.5 ± 6.9 | 3.2 ± 0.3 | 11 (55%) | ||||||||

| 0 | 13.8 ± 3.9 | ||||||||||

| 0 | |||||||||||

| DPPHR (Berne) | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 (85%) | 15 (75%) | NA | NA | |||

| 0 | 142.5 ± 4.9 | 7.8 ± 0.9 | 5 (25%) | ||||||||

| 0 | 8.5 ± 0.9 | ||||||||||

| 0 | |||||||||||

| Köninger et al. [75] | 2008 | RCT (Ib) | DPPHR (Beger) | 32b | 6 (20%) | 0 | 8 (27% pat) | NA | NA | NA | 65.6 ± 24.8 |

| 2 (6%) | 369 ± 91 | 1.9 (at discharge) | |||||||||

| 0 | 15 (8–47) | ||||||||||

| 1 (3%) | |||||||||||

| DPPHR (Berne) | 33b | 7 (21%) | 0 | 6 (20%pat) | NA | NA | NA | 71.3 ±21.6 | |||

| 0 | 323 ± 56 | 0.4 (at discharge) | |||||||||

| 1 (3%) | 11 (8–39) | ||||||||||

| 1 (3%) | |||||||||||

| Izbicki et al. [68] | 1995 | RCT (Ib) | DPPHR (Beger) | 20 | 4 (20%) | 0 | 3.83 ± 2.4 | 95% | 90% | 1 | No difference between the two procedures |

| NA | 325 ± 77 | 6.7 ± 2.1 | NA | ||||||||

| 1 (5%) | NA | ||||||||||

| 1 (5%) | |||||||||||

| DPPHR (Frey) | 22 | 2 (9%) | 0 | 2.49 ±2.3 | 89% | 77% | 1 | ||||

| NA | 289 ± 89 | 6.4 ± 2.5 | NA | ||||||||

| 0 | NA | ||||||||||

| 1 (4.5%) | |||||||||||

| Izbicki et al. [69] | 1997 | RCT (Ib) | DPPHR (Beger) | 38 | 12 (32%) | 0 | 2 (5% pat) | 89% | 74% | 3 (8%) | No difference between the two procedures |

| NA | 315 ±91 | 6.4 ± 2.3 | NA | ||||||||

| 3 (8%) | NA | ||||||||||

| 2 (5%) | |||||||||||

| DPPHR (Frey) | 36 | 8 (22%) | 0 | 1 (3% pat) | 92% | 69% | 2 (6%) | ||||

| NA | 284 ± 79 | 6.2 ± 2.5 | NA | ||||||||

| 2 (6%) | NA | ||||||||||

| 1 (3%) | |||||||||||

| Strate et al. [70] | 2005 | RCT (Ib) | DPPHR (Beger) | 26 (8 dead, 4 lost to F/U) | See above | 8/34 | See above | No difference between procedures | NA | 14/25 22/25 (88%) | No difference between the two procedures |

| Long-term F/U of Izbicki 1997 trial | DPPHR (Frey) | 25 (8 dead, 3 lost to F/U) | See above | 8/33 | See above | NA | 15/25 18/23 (60%) | ||||

| Müller et al. [73] | 2008 | Prospective study | DPPHR (Berne) | 100 | 23 (23%) | 1 (1%) | 0.15 (0–8) | Pain improved in 55% | 49/73 (67%) | 12/55 (22%) | 66.4 ± 2.6 |

| 1 (1%) | 295 ±7 | NA | 56/73 (77) | ||||||||

| 1 (1%) | 11.4 ± 0.8 | ||||||||||

| 3 (3%) |

- Evidence level Ib: individual properly designed randomized controlled trial;

- Evidence level IIb: individual well-designed controlled trial without randomization, retrospective cohort study

- PD, pancreaticoduodenectomy; ppPD, pylorus-preserving PD; DPPHR, duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection; DGE delayed gastric emptying; DM diabetes mellitus; RCT randomized controlled trial. NRCT: non-randomized controlled trial. SD standard deviation. NA not available; EORTC European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer; F/U follow up

- a Data shown for 14-year follow up

- b In the trial of Köninger et al., 8 patients in the Beger group and 6 in the Berne group were converted to other procedures during the initial operation, but were included in the intention-to-treat analysis

Recently, a long-term (7- and 14-year) follow up of the RCT by Büchler et al. [62] was published [67]. Five of the 20 patients enrolled in each group died during a follow-up period of 14 years. The 5-year survival rate was 90% in both groups. Deaths were due to comorbidities common in patients with CP (liver cirrhosis, renal insufficiency, myocardial infarction, etc.). Contrary to the initial results after 6 months, evaluation of pain showed no differences between the two groups at 7 and 14 years' follow up. Furthermore, no significant difference in the onset of diabetes mellitus was apparent between the two groups (at 14 years, 4 of 11 patients in the Beger group compared to 6 of 9 patients in the ppPD group). In addition, evaluation of the QOL was similar in the two groups, the only marked difference being appetite loss, which was more pronounced in the ppPD group (p = 0.044). Interestingly, patient judgment after 14 years demonstrated a significant advantage in terms of subjective wellbeing in the Beger group (p = 0.022). In summary, the significant initial advantages of Beger's DPPHR in comparison with ppPD were less apparent after a prolonged follow up of 7 to 14 years. It should be mentioned, however, that the long-term follow up was hampered by a small number of patients being analyzed. Another point is noteworthy; namely, that two patients in the Beger group required reoperation (one for common bile duct stenosis, one for stenosis of the pancreaticojejunostomy), indicating a potential disadvantage of the organ-sparing DPPHR in comparison to the more radical ppPD.

Based on the currently available data, significant advantages of the Beger's operation over PD and ppPD exist in terms of weight gain, pain control, and endocrine function for up to 4 years after surgery. Improved rehabilitation, endocrine function, and QOL persist even after this time. We therefore regard Beger's DPPHR as superior to PD or ppPD in the surgical treatment of CP, if it can be applied.

Comparison of Beger's operation with Frey's procedure

Two RCTs have been performed to compare Beger's operation with the modification introduced by Frey [68, 69]. These studies showed comparable levels of pain relief (ranging between 93 and 95%) and control of complications to adjacent organs (91% Frey, 92% Beger), as well as improvement in the QOL (58–67% increase in the overall QOL index). Furthermore, endocrine and exocrine function of the pancreas were not significantly different between the two groups. A long-term follow up (median, 104 months) of one of these studies [69] showed that there was no difference in late mortality (31 vs. 32%), endocrine or exocrine function, or pain scores (Izbicki pain scores, 11.25 vs. 11.25) or QOL (European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer [EORTC] global QOL 66.7 vs. 58.35) [70].

Results of the Berne operation

The Berne modification of Beger's procedure [59] was initially evaluated in several smaller studies [71, 72]. Farkas et al. reported 30 patients who, after a mean follow up of 10 months, were all symptom-free, had experienced no severe complications, and showed enhanced endocrine and exocrine function [71]. Similar results were reported by Andersen and Topazian [72]. Recently, the prospectively evaluated data of a large series of 100 consecutive CP patients treated with the Berne operation at a single institution were published [73]. With a low postoperative mortality rate (1%) and low surgical morbidity (16%), as well as pain improvement in 55% of all patients, weight gain in 67%, and QOL comparable to that of a healthy control population at a mean follow up of 41 months, the Berne modification has become an established option for the treatment of CP.

Two randomized trials have been reported up to now comparing the Berne procedure either to ppPD [74] or to Beger's operation [75]. Farkas and colleagues randomly assigned 40 patients to either undergo the Berne operation (20 patients) or ppPD (20 patients). Operation time was significantly shorter in the Berne group (142 ± 4.9 vs. 278 ± 6.9 min for ppPD), as was the duration of hospital stay (Berne 8.5 ± 0.9 days vs. 13.8 ± 3.9 for ppPD). In this study, postoperative morbidity was markedly increased in the ppPD group (Berne 0% vs. ppPD 40%), largely due to an unexpectedly high morbidity in the ppPD group not reported in other studies (see Table 1). At follow up (1 year) there was no significant difference in complete pain relief (Berne 85% vs. 90% ppPD); however, weight gain occurred in significantly more patients in the Berne subgroup (75 vs. 30% in the ppPD group), with an average weight gain of 7.8 ± 0.9 kg versus only 3.2 ± 0.3 kg in the ppPD group. Furthermore, patients in the Berne group exhibited a significantly better QOL.

Köninger et al. conducted a RCT comparing Beger's original DPPHR to the Berne modification [75]. In this trial 65 patients were randomly assigned to undergo either Beger's operation (32 patients) or the Berne modification (33 patients). The primary end point of this analysis was operation time, which was significantly shorter in the Berne group than in the Beger group (323 ± 56 vs. 369 ± 91 min, p = 0.02). Furthermore, mean hospital stay was shorter in the Berne group (11 vs. 15 days, p = 0.15). QOL did not differ significantly after 2 years between the two groups regarding the EORTC-QLQ-30 questionnaire (Beger 65.5% vs. Berne 71.3%). A significant difference found between the two groups on the pancreas-specific EORTC-PAN questionnaire in favor of the Berne procedure (Beger 63.9% vs. Berne 75.8%) persisted only in the intention-to-treat analysis. In the per-protocol analysis, operation time remained the only significant difference between the two procedures. Notably, 11 patients (6 in the Beger group and 5 in the Berne group) required readmission to hospital and reoperation due to the disease. Three of the Berne group patients were operated on due to ongoing pancreatitis and bile duct obstruction, indicating the importance of removing as much pancreatic head tissue as possible during the operation.

In summary, the Berne modification seems to be equally suited for the treatment of CP as the original Beger's operation.

Conclusion

Beger's DPPHR and the Berne and other modifications are by now well-established and analyzed procedures for the treatment of CP. Both the Beger and the Berne procedures, as well as the other modifications, are organ-sparing pancreatic head resections specifically tailored for the treatment of CP. The superior outcome of these procedures over pancreaticoduodenectomies (PD or ppPD) in terms of weight gain and pain control, as well as endocrine and intestinal function, make them the ideal treatment options for patients requiring surgery for CP, although after long-term follow up some of the initial advantages are lost.