Validity and utility of Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP): III. Emotional dysfunction superspectrum

Abstract

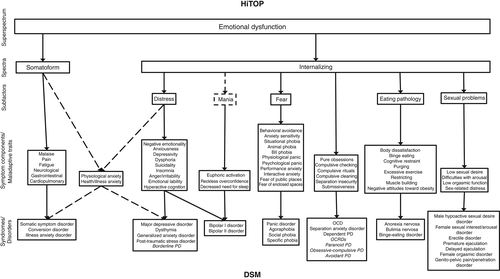

The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP) is a quantitative nosological system that addresses shortcomings of traditional mental disorder diagnoses, including arbitrary boundaries between psychopathology and normality, frequent disorder co-occurrence, substantial heterogeneity within disorders, and diagnostic unreliability over time and across clinicians. This paper reviews evidence on the validity and utility of the internalizing and somatoform spectra of HiTOP, which together provide support for an emotional dysfunction superspectrum. These spectra are composed of homogeneous symptom and maladaptive trait dimensions currently subsumed within multiple diagnostic classes, including depressive, anxiety, trauma-related, eating, bipolar, and somatic symptom disorders, as well as sexual dysfunction and aspects of personality disorders. Dimensions falling within the emotional dysfunction superspectrum are broadly linked to individual differences in negative affect/neuroticism. Extensive evidence establishes that dimensions falling within the superspectrum share genetic diatheses, environmental risk factors, cognitive and affective difficulties, neural substrates and biomarkers, childhood temperamental antecedents, and treatment response. The structure of these validators mirrors the quantitative structure of the superspectrum, with some correlates more specific to internalizing or somatoform conditions, and others common to both, thereby underlining the hierarchical structure of the domain. Compared to traditional diagnoses, the internalizing and somatoform spectra demonstrated substantially improved utility: greater reliability, larger explanatory and predictive power, and greater clinical applicability. Validated measures are currently available to implement the HiTOP system in practice, which can make diagnostic classification more useful, both in research and in the clinic.

The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP) uses data from studies on the organization of psychopathology to construct a quantitative nosological system1-4. The HiTOP organizes psychopathology into a multilevel hierarchical structure. Hierarchical structures connect phenomena representing varying levels of specificity, i.e., a broader dimension at one level can be decomposed into more specific dimensions at lower levels. The broader dimension represents shared features that produce a correlation between the more specific dimensions; however, these specific variables still contain their own unique aspects and can be differentiated at a more fine-grained level. For example, diagnoses of major depressive disorder (MDD) and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) tend to co-occur in individuals and, therefore, are strongly correlated with one another2, 5-7. Consequently, they both can be subsumed within broader dimensional constructs, such as distress disorders2, 4. However, MDD and GAD have distinctive features that need to be modeled in any comprehensive structure.

The lower levels of the HiTOP hierarchy contain specific, homogeneous symptom dimensions (e.g., insomnia) and maladaptive traits (e.g., irritability). These homogeneous elements can be combined into dimensional syndromes, some of which roughly correspond to traditional diagnoses such as MDD and GAD. Similar syndromes are combined into subfactors, such as the class of distress disorders that includes MDD and GAD. Larger constellations of syndromes form broader spectra, such as internalizing. Finally, these spectra can be aggregated into extremely broad superspectra, ultimately leading to a general factor of psychopathology2, 8-10.

The HiTOP currently includes six spectra2. These spectra can be conceptualized as forming three superspectra: psychosis (combining thought disorder and detachment), externalizing (subsuming disinhibited and antagonistic forms of psychopathology), and emotional dysfunction (modeling the commonality between internalizing and somatoform). Although these superspectra were not formalized in the original HiTOP system, they are supported by evidence reviewed in a series of papers published in this journal. The first paper11 focused on the psychosis superspectrum, whereas the second12 examined externalizing; this paper discusses the emotional dysfunction superspectrum.

The HiTOP model resolves widely recognized problems of traditional nosologies. First, traditional taxonomies consider mental disorders to be discrete categories, whereas the data show that virtually all major forms of psychopathology exist on a continuum with normality13-19. Consequently, systems based on dichotomous diagnoses lead to a substantial loss of clinically significant information14, 20-22. Most notably, many patients fall short of the criteria for any disorder, despite experiencing clinically significant impairment. The HiTOP solves this problem by assessing psychopathology as a series of continuous dimensions. No patients are excluded from the system, because even those with subthreshold or atypical symptoms can be characterized on a comprehensive set of dimensions. Moreover, dimensions capture clinically important differences in symptom severity among individuals who do meet criteria for a disorder14.

Second, dichotomous diagnoses show limited reliability, both over time and across clinicians23-25. For instance, the DSM-5 field trials found that many common diagnoses – including MDD (kappa = .28) and GAD (kappa = .20) – did not meet even a relaxed cutoff for acceptable interrater reliability25. Again, the HiTOP addresses this problem by modeling psychopathology dimensionally: extensive evidence establishes that the same clinical phenomena are much more reliable when assessed continuously22, 26-30.

Third, many diagnoses are heterogeneous and encompass diverse characteristics6, 14, 31, 32. This problem is exacerbated by the fact that current nosological systems make ample use of polythetic diagnoses, such that a patient only needs to meet a specified number of criteria to have a disorder. For example, a patient needs to meet only five of nine criteria to be diagnosed with MDD in the DSM-533, which means that there are 227 possible ways to receive this diagnosis32; this number increases to 16,400 if one takes into account different symptom presentations within criteria (e.g., insomnia vs. hypersomnia)34. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) represents an extreme example of the combinatorial problem with polythetic diagnoses, given that there are 636,120 possible ways to receive this DSM-5 diagnosis35. Consequently, patients with the same diagnosis can present with very different problems and may have few – if any – overlapping symptoms34, 36. The HiTOP addresses this problem by decomposing broader syndromes into homogeneous dimensions at lower levels of the hierarchy.

Fourth, comorbidity is a pervasive problem in traditional taxonomies5-7, 37-43. We already have noted the strong comorbidity between MDD and GAD. High comorbidity suggests that unitary conditions have been split (perhaps arbitrarily) into multiple diagnoses, which co-occur frequently in individuals as a result. The HiTOP addresses this problem by modeling comorbidity directly. Indeed, the HiTOP structure essentially represents empirical patterns of correlations/comorbidity, i.e., strongly correlated conditions are placed near to one another (e.g., in the same spectrum), whereas less strongly related phenomena are located farther apart (e.g., in different spectra). This hierarchical system is highly flexible, such that clinicians and researchers can focus on whatever level is most informative for a given problem2, 44.

In this paper, we examine the HiTOP emotional dysfunction superspectrum. As noted, this superspectrum represents the commonality of the internalizing and somatoform spectra.

STRUCTURAL EVIDENCE

Internalizing spectrum

Internalizing is the largest and most complex of the HiTOP spectra. It consistently emerges as a distinct spectrum in structural analyses. However, the composition of this spectrum is critically dependent on the specific variables included in the analysis. Table 1 summarizes findings from the large number of studies that have modeled internalizing using diagnostic data8, 9, 45-87. Internalizing clearly subsumes a very broad range of psychopathology, including content related to depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive and related disorders, trauma- and stressor-related disorders, eating disorders, and personality disorders.

| N | Sample type | DEP | DYS | GAD | PTSD | PAN | AGO | SOC | SPE | OCD | BPD | MAN | SAD | AN | BN | BED | PSY | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internalizing | ||||||||||||||||||

| Dunedin Study (Caspi et al8, Krueger et al45) | 1,037 | Community/longitudinal | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||

| MIDAS (Forbes et al46, Kotov et al47) | 2,900 | Outpatients/adults | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | – | |||

| NCS (Levin-Aspenson et al48) | 8,098 &5,877 | Community/adults | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | +/– | ||||||

| NESARC (Keyes et al49, Kim & Eaton50) | 43,093 &34,653 | Community/adults | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| Norwegian Twin Panel (Kendler et al51, Røysamb et al52) | 2,794 | Community/adults | + | +/– | + | + | + | + | +/– | + | +/– | + | ||||||

| WMH Surveys (Kessler et al53) | 21,229 | Community/longitudinal | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||

| Conway & Brown54 | 4,928 | Outpatients/adults | + | + | + | + | – | + | – | – | – | – | ||||||

| Conway et al55 | 25,002 | University/adults | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | ||||

| Conway et al56 | 815 | Community/longitudinal | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| Farmer et al57 | 816 | Community/longitudinal | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| Girard et al58 | 825 | Mixed/adults | + | – | – | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| King et al59 | 1,329 | Community/young adults | + | + | + | + | + | – | ||||||||||

| Kotov et al60 | 469 | Inpatients/adults | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||

| Martel et al61 | 2,512 | Community/children | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||

| Martel et al61 | 8,012 | Community/adults | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| Olino et al62 | 541 | Community/children | + | + | + | – | – | – | + | |||||||||

| Schaefer et al63 | 2,232 | Community/adolescents | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| Scott et al64 | 156 | Community/young women | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||

| Verona et al65 | 4,745 | Community/adults | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||

| Verona et al66 | 223 | Mixed/youth | + | + | ||||||||||||||

| Wright & Simms67 | 628 | Outpatients/adults | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | + | – | |||||||

| Total positive | 21/21 | 10.5/12 | 19/20 | 14/14 | 18/19 | 7/8 | 15.5/17 | 12/15 | 8/10 | 4.5/6 | 6/9 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 3/3 | 2.5/5 | ||

| Distress | ||||||||||||||||||

| EDSP (Beesdo-Baum et al68, Wittchen et al69) | 3,021 | Community/longitudinal | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| NCS (Cox et al70, Krueger71, Levin-Aspenson et al48) | 8,098 & 5,877 | Community/adults | + | + | + | +/– | +/– | +/– | – | – | +/– | +/– | ||||||

| NESARC (Eaton et al72,73, Keyes et al74, Kim & Eaton50, Lahey et al9) | 43,093 & 34,653 | Community/adults | + | + | + | + | +/– | +/– | – | + | + | |||||||

| WMH Surveys (de Jonge et al75) | 21,229 | Community/longitudinal | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| Blanco et al76 | 9,244 | Community/adolescents | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| Conway et al55 | 25,002 | University/adults | + | + | + | + | – | |||||||||||

| Forbush & Watson77 | 16,423 | Community/adults | + | + | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |||

| Forbush et al78 | 1,434 | Community/longitudinal | + | + | ||||||||||||||

| James & Taylor79 | 1,197 | Community/adults | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||

| Kotov et al80 | 385 & 288 | Mixed/adults | + | + | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | |||||||

| Martel et al61 | 2,512 | Community/children | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| Martel et al61 | 8,012 | Community/adults | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| Miller et al81 | 1,325 | Veterans/adults | + | + | ||||||||||||||

| Miller et al82 | 214 | Veterans/adults | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||

| Mitchell et al83 | 760 | Mixed/adults | + | + | + | +/– | + | + | ||||||||||

| Slade & Watson84 | 10,641 | Community/adults | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||

| South et al85 | 1,858 | Community/adults | + | + | ||||||||||||||

| Vollebergh et al86 | 7,076 | Community/adults | + | + | + | |||||||||||||

| Wright et al87 | 8,841 | Community/adults | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| Total positive | 19/19 | 13/13 | 17/17 | 9.5/10 | 3/5 | 0.5/3 | 1.5/5 | 0/4 | 3/4 | 3/4 | 5.5/9 | 1/1 | 3.5/5 | 5/6 | 5/6 | 1.5/2 | ||

| Fear | ||||||||||||||||||

| EDSP (Beesdo-Baum et al68, Wittchen et al69) | 3,021 | Community/longitudinal | + | + | +/– | + | ||||||||||||

| NCS (Cox et al70, Krueger71, Levin-Aspenson et al48) | 8,098 &5,877 | Community/adults | +/– | – | +/– | +/– | + | + | + | + | +/– | – | ||||||

| NESARC (Eaton et al72,73, Keyes et al74, Kim & Eaton50, Lahey et al9) | 43,093 & 34,653 | Community/adults | – | – | +/– | + | + | + | + | + | – | |||||||

| WMH Surveys (de Jonge et al75) | 21,229 | Community/longitudinal | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||

| Blanco et al76 | 9,244 | Community/adolescents | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||

| Conway et al55 | 25,002 | University/adults | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||

| Forbush & Watson77 | 16,423 | Community/adults | – | – | – | – | + | + | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | |||

| Forbush et al78 | 1,434 | Community/longitudinal | + | + | ||||||||||||||

| James & Taylor79 | 1,197 | Community/adults | + | + | ||||||||||||||

| Kotov et al80 | 385 & 288 | Mixed/adults | – | – | – | – | + | + | + | + | – | |||||||

| Martel et al61 | 2,512 | Community/children | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| Martel et al61 | 8,012 | Community/adults | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| Miller et al81 | 1,325 | Veterans/adults | + | + | + | |||||||||||||

| Miller et al82 | 214 | Veterans/adults | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||

| Mitchell et al83 | 760 | Mixed/adults | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||

| Slade & Watson84 | 10,641 | Community/adults | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||

| South et al85 | 1,858 | Community/adults | + | + | + | |||||||||||||

| Vollebergh et al86 | 7,076 | Community/adults | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||

| Wright et al87 | 8,841 | Community/adults | + | + | + | |||||||||||||

| Total positive | 0.5/4 | 0/3 | 1/4 | 1.5/4 | 17/18 | 15/15 | 15.5/16 | 15/15 | 6/6 | 0/1 | 0.5/4 | 2/2 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 |

- +: indicator included in analysis and loaded ≥.30, –: indicator included in analysis but loaded <.30, +/–: inconsistent loadings across models or individual studies (counted as 0.5 in the total), DEP – major depression, DYS – dysthymia, GAD – generalized anxiety disorder, PTSD – post-traumatic stress disorder, PAN – panic, AGO – agoraphobia, SOC – social phobia, SPE – specific phobia, OCD – obsessive-compulsive disorder, BPD – borderline personality disorder, MAN – mania, hypomania or bipolar disorder, SAD – separation anxiety disorder, AN – anorexia nervosa, BN – bulimia nervosa, BED – binge-eating disorder, PSY – psychotic disorder, MIDAS – Methods to Improve Diagnostic Assessment and Services, NCS – National Comorbidity Survey, NESARC – National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, WMH – World Mental Health, EDSP – Early Developmental Stages of Psychopathology

Several subfactors have been identified within internalizing. Table 1 presents findings related to the two broadest and best replicated subfactors2. First, the distress subfactor includes disorders that involve pervasive negative emotionality6, such as MDD, dysthymic disorder, GAD and PTSD. Second, the fear subfactor is defined by disorders that involve more specific, context-delimited forms of distress and that frequently include behavioral avoidance, such as panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, and specific phobia. These distress and fear subfactors are strongly correlated, and some studies have found them to be indistinguishable47, 52, 67. Relatedly, some diagnoses – such as obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) – do not fall clearly into either subfactor.

Growing evidence indicates that eating pathology forms a third subfactor within internalizing2, 77, 78, 88, although it is sometimes included in the distress subfactor (Table 1). At the syndrome level, this cluster is defined by disorders such as bulimia nervosa, anorexia nervosa, and binge eating disorder77, 78. At the symptom level, structural/psychometric evidence has established the existence of eight specific dimensions: body dissatisfaction, binge eating, cognitive restraint, purging, excessive exercise, restricting, muscle building, and negative attitudes toward obesity. These eight dimensions have been replicated across a variety of populations89-92.

Evidence has also emerged for a fourth subfactor of sexual problems2, 93-95. This cluster is defined by multiple symptoms of sexual dysfunction, including low sexual desire, difficulties with arousal, low orgasmic function, and sex-related distress.

Finally, several studies have found that indicators of mania/bipolar disorder fall within the internalizing spectrum and often help to define its distress subfactor. However, other studies have linked mania to the thought disorder spectrum8, 47, 49. Accordingly, mania is currently an interstitial construct in HiTOP, with important connections to both internalizing and thought disorder. Mania subsumes several distinct symptom dimensions, including emotional lability, euphoric activation, hyperactive cognition, reckless overconfidence, and irritability96-100. These symptom dimensions have distinctive correlates, and more fine-grained analyses will likely reveal that they are located in different HiTOP spectra.

Somatoform spectrum

Somatoform is currently the most tentative of the HiTOP spectra2. Early evidence suggested that somatoform psychopathology was subsumed within internalizing, based on data that somatization, hypochondriasis and neurasthenia loaded with depression and anxiety on a broader internalizing factor101, 102. However, subsequent research has shown that, when a sufficient set of indicators is available, the somatoform spectrum is indeed separate from internalizing as well as the other HiTOP spectra46, 47, 102, 103, 105, 107-117. These seemingly divergent sets of findings can easily be reconciled. Several studies46, 104, 106 have demonstrated convincingly that internalizing and somatoform do form a single spectrum at very broad levels of the hierarchy, but, as one moves further down in levels of abstraction, somatoform separates from internalizing.

Table 2 lists 16 studies46, 47, 102, 103, 106-117 conducted across a diverse range of countries – and using a wide range of populations and measurement modalities – that have yielded support for a higher-order somatoform factor. The indicators have mostly represented an array of bodily distress symptoms (e.g., pain, gastrointestinal, cardiopulmonary, chronic fatigue, functional neurological), akin to the bodily distress syndrome proposed by Fink and colleagues118, 119. Although the broader categorical hypochondriasis diagnostic construct has loaded on the somatoform factor in the two studies in which it was included, this construct is multifactorial in nature120; it therefore would be important to determine the degree to which the components of cognitive preoccupation, bodily perceptions, reassurance seeking, and hypochondriacal worry load on this somatoform factor. Indeed, absent from all these studies are specific indicators reflecting health anxiety, which clearly includes aspects of both internalizing (i.e., anxious apprehension and fearfulness) and somatoform (i.e., somatic preoccupation and disease conviction) pathology. Future studies need to elucidate the placement of health anxiety in the hierarchy.

| N | Sample type | Measure | General malaise | Pain | Neurological | Gastrointestinal | Fatigue | Cardiopulmonary | Somatic anxiety | Hypochondriasis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cano-García et al107 | 1,255 | Primary care | PHQ-15 | + | + | + | + | ||||

| Budtz-Lilly et al108 | 2,480 | Primary care | BDS Scale | + | + | + | + | ||||

| Deary109 | 315 | Mixed | DSM-III-R questionnaire | + | + | + | + | + | |||

| Gierk et al110 | 2,510 | Community | SSS-8 | + | + | + | + | ||||

| Leonhart et al111 | 2,517 456, 1,329 |

Routine clinical care General hospital |

PHQ-15 | + | + | + | + | ||||

|

Marek et al103 |

810 533 |

Spine surgery patients Spinal cord stimulator patients |

MMPI-2-RF | + | + | + | + | – | |||

| McNulty & Overstreet112 | 925 1,199 |

Outpatient psychiatric Inpatient psychiatric |

MMPI-2-RF | +,+ | +,+ | +,+ | +,+ | +,– | |||

| MIDAS (Forbes et al46, Kotov et al47) | 2,900 | Outpatient psychiatric | SCID-I | + | + | + | |||||

| Schmalbach et al113 | 2,386 | Community | BDS Scale | + | + | + | + | ||||

| Sellbom105 | 895 42,290 |

Outpatient psychiatric Inmates |

MMPI-2-RF | +,+ | +,+ | +,+ | +,+ | +,– | |||

| Simms et al102 | 5,433 | Primary care | CIDI | + | + | + | |||||

| Thomas & Locke114 | 399 | Epilepsy/NES patients | MMPI-2-RF | + | + | + | + | ||||

| Walentynowicz et al115 | 1,053 | University | PHQ-15 | + | + | + | + | ||||

| Witthöft et al116 | 414 308 |

Community Primary care |

PHQ-15 | + | + | + | + | ||||

| Witthöft et al117 | 1,520 3,053 | University | PHQ-15 | + | + | + | + | ||||

| Total positive | 11/11 | 16/16 | 7/7 | 15/15 | 7/7 | 8/8 | 3/6 | 2/2 |

- +: indicator included in analysis and loaded ≥.30, –: indicator included in analysis but loaded <.30, MIDAS – Methods to Improve Diagnostic Assessment and Services, PHQ-15 – Patient Health Questionnaire-15, BDS Scale – Bodily Distress Syndrome Scale, SSS-8 – Somatic Symptom Scale-8, MMPI-2-RF – Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 Restructured Form, SCID-I – Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, CIDI – Composite International Diagnostic Interview, NES – non-epileptic seizures. General malaise includes undifferentiated somatoform symptoms, somatic depression, cognitive symptoms; pain includes fibromyalgia, musculoskeletal symptoms; neurological includes neurasthenia, conversion disorder; somatic anxiety includes physiological symptoms of anxiety (not health anxiety).

Role of maladaptive traits

Negative affect/neuroticism (NA/N) is a fundamental trait domain in research on personality and personality pathology. It also is a key part of the DSM-5 alternative model of personality disorders, as well as a trait qualifier in the new ICD-11 personality disorder diagnosis121. NA/N cuts across and ties together propensities to experience diverse negative emotional experiences – because these experiences are highly correlated – and thereby represents the central feature of internalizing. Indeed, cross-sectional data show that individual differences in broadly conceptualized internalizing psychopathology and NA/N are very highly correlated and essentially fungible121-123.

NA/N is a higher-order dimension that subsumes many more specific facets, which are also strongly related to various forms of internalizing. Specific facets of NA/N include anxiousness, depressivity, anger/irritability, separation insecurity, and emotional lability2, 124-126, as well as social cognitive vulnerabilities such as anxiety sensitivity, self-criticism, rumination, hopelessness, and perfectionism. It is noteworthy that these social cognitive vulnerabilities show unique associations with internalizing syndromes127-130. For example, anxiety sensitivity is associated with panic and other syndromes, net of the general NA/N association with internalizing128. In addition, other major personality domains act synergistically with NA/N to affect the likelihood of experiencing specific forms of internalizing. For example, extraversion and conscientiousness mitigate the impact of NA/N on specific internalizing syndromes, such as depression131, 132.

NA/N traits also are predictive of future episodes of internalizing disorders133-135. Indeed, NA/N can be simultaneously conceptualized as a vulnerability for internalizing disorder, sharing causes with internalizing disorder, and lying within the same spectrum of human variation as internalizing disorder136, 137. These connections may emerge from dynamic processes in which NA/N enhances stress, promoting internalizing symptomatology, and feeding back on general stress reactivity to further reinforce NA/N tendencies138, 139.

The strong association between NA/N and internalizing has led to a focus on articulating shared mechanisms and specific points of continuity137. Twin research shows that the close phenotypic overlap of NA/N and internalizing psychopathology is undergirded by shared genetic risk factors140, 141. Distally, emerging molecular evidence also points to a genetic basis for NA/N-internalizing connections142. More proximally, shared neurocircuitry linking neuroticism to emotional dysregulation may constitute some of the manifest mechanisms underlying close NA/N-internalizing connections143.

Finally, NA/N is broadly related to health complaints and somatic symptoms144; in fact, some models include somatic complaints as a specific facet within this domain125, 145. NA/N has also been shown to be substantially associated with overreporting of health complaints144, medically unexplained symptoms146-149, health anxiety and hypochondriasis120, 150-156, and somatization/somatization disorder157-160.

NA/N is broadly related to the symptoms, traits and disorders subsumed within the somatoform spectrum and, therefore, is partly responsible for its emergence in structural studies. Because NA/N is also broadly linked to the internalizing spectrum, it further helps to explain the existence of the emotional dysfunction superspectrum161, which reflects important commonalities between somatoform and internalizing psychopathology.

Overall model

Figure 1 summarizes the proposed model of the emotional dysfunction superspectrum and its constituent spectra. The sections for internalizing and somatoform build upon the current HiTOP model2 in light of the literature reviewed in this paper – in particular, highlighting those areas whose placement within this superspectrum is ambiguous or tentative. The model also includes illustrative symptom and trait dimensions that populate the lower levels of the hierarchy; these are taken from Kotov et al2 and subsequent studies.

Internalizing consistently emerges as a distinct dimension in structural models, but its boundaries are unclear. For example, internalizing is strongly characterized by personality pathology related to NA/N121-123. However, personality disorders that load on internalizing (e.g., borderline and avoidant) often cross over into other spectra (externalizing and detachment, respectively46, 58).

Table 1 demonstrates substantial support for subdividing internalizing into distress and fear subfactors, but evidence for the distress-fear distinction is not universal46, 52, 55, 56, 67. Some studies have found evidence for additional subfactors of internalizing, including sexual problems93-95 and eating pathology77, 78, although eating pathology may form a separate structural dimension55.

The somatoform spectrum is defined by a wide array of somatic complaints, as well as preoccupation with bodily symptoms. Somatoform problems covary substantially with internalizing psychopathology52 and, as with internalizing, somatoform psychopathology is strongly associated with individual differences in NA/N144. Nevertheless, a somatoform spectrum can be distinguished from the internalizing one if a sufficient set of indicators is available46, 103, 105.

VALIDITY EVIDENCE

Behavioral genetics

Twin studies suggest that the internalizing domain is moderately heritable and under shared genetic influences51, 140, 141, 162-167. A substantial proportion of these genetic influences is also shared with externalizing, but the remaining vulnerability is specific to the internalizing spectrum. Importantly, these studies usually defined the internalizing spectrum as emotional problems, and the strongest genetic loadings were for MDD and GAD163. Within this narrower conceptualization of internalizing, there is evidence for separate genetic influences on distress and fear168-170.

No study has examined genetic and environmental influences on all of the symptoms and traits subsumed within internalizing. However, it is possible to piece together how different HiTOP internalizing syndromes are genetically related from the research that does exist across different combinations of disorders. Multiple forms of eating pathology have common genetic vulnerability171-173. Moreover, twin studies indicate a shared genetic risk for eating pathology and emotional problems, including anxiety and depression symptoms51, 174-177. There is also a substantial genetic correlation between anorexia nervosa and OCD178. Finally, twin and family studies indicate a partial genetic overlap between mania and unipolar depression179-181, although the genetic association between mania and schizophrenia is substantially stronger182-185. Overall, there is prominent genetic overlap between different conditions within internalizing – except for mania – although there is no research on the genetic overlap with sexual problems.

In contrast, twin studies suggest that a significant proportion of genetic influences on somatoform spectrum symptoms are independent from internalizing problems186, 187. For example, a common genetic factor contributes to four somatic symptoms: recurrent headache, irritable bowel syndrome, chronic impairing fatigue, and chronic widespread pain188, independent of genetic influences shared with MDD and GAD. Nonetheless, the somatoform and internalizing spectra may share genetic underpinnings at a higher level of generality51, 186-191.

Overall, twin studies support shared genetic influences on the internalizing spectrum that are partially distinct from the genetic etiology of the somatoform spectrum. Future twin studies should assess a wider range of variables to test the genetic architecture comprehensively.

Molecular genetics

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) detect genetic variants across the entire genome and allow one to compute molecular genetic correlations between traits192. Many genetic variants, each with a small effect size, have been found to contribute to the shared risk for internalizing. For example, depression shows high genetic correlations with generalized anxiety, NA/N, anhedonia, and PTSD (rg>0.70)193-196, as well as much smaller but significant genetic correlations with bipolar disorder, OCD, and anorexia nervosa (rg=0.17-0.36)197.

Genomic structural equation modeling (SEM) is another technique for investigating shared genetic influences across related conditions. It can extract common genetic dimensions from a set of molecular genetic correlations, and is thus useful for testing the genome-wide architecture of psychopathology. Using this approach, Waldman et al198 identified a genetic internalizing factor, characterized by shared genetic influences on depression, anxiety and PTSD. However, bipolar disorder, OCD and anorexia nervosa were influenced by a genetic thought problems factor, rather than by internalizing. Lee et al197 found that OCD and anorexia nervosa were influenced by a separate genetic factor from depression, whereas bipolar disorder had a uniquely strong association with schizophrenia (rg=0.70). Finally, Levey et al199 identified a genetic internalizing factor, which captured shared genetic influences on depression, NA/N, PTSD and anxiety.

Overall, genomic SEM supports a narrow internalizing factor that captures shared genetic influences on distress and fear disorders. Anorexia nervosa and OCD share a separate genetic factor in these studies, in line with the moderate genetic correlation between these conditions (rg=0.45)200. Furthermore, the genetic vulnerability to bipolar disorder appears to align more closely with thought disorder than with internalizing. However, the high genetic overlap between schizophrenia and bipolar disorder is more specific to bipolar disorder I than bipolar disorder II (rg=0.71 vs. 0.51), whereas depression is more closely correlated with bipolar disorder II than bipolar disorder I (rg=0.69 vs. 0.30)201. Similarly, bipolar disorder cases with psychosis have higher genetic risk for schizophrenia but lower risk for anhedonia, whereas bipolar cases with a suicide attempt have elevated genetic risk for depression and anhedonia202.

Molecular genetic studies also provide evidence for a genetic distinction between distress and fear factors. Depression and generalized anxiety show a substantial genetic overlap (rg=0.80), but are partly genetically distinct from fear disorders, such as specific phobia and panic (rg=0.34 and 0.63, respectively)203. Moreover, depression and anxiety were influenced by two distinct but genetically correlated factors (rg=0.80), while NA/N items were partitioned between them204. Likewise, the molecular genetic architecture of NA/N consists of two genetically correlated factors, corresponding to distress and fear142, 205, 206.

As additional GWAS summary statistics become available, more fine-grained models of internalizing can be tested. Furthermore, although there is no GWAS of somatoform spectrum disorders, moderate genetic correlations between chronic pain and depression, anxiety and NA/N (rg=0.40-0.59) suggest that there may be considerable genetic overlap between the internalizing and somatoform spectra, that is captured by the emotional dysfunction superspectrum207, 208. Finally, genetic correlations can be affected by the heterogeneous psychiatric diagnoses used in GWAS. Homogeneous symptom dimensions can address this heterogeneity and enhance gene discovery209-211.

Environmental risk factors

Environmental variation shapes the development of all forms of emotional disorder212. A vast literature attests to this fact, but studies focus primarily on a single diagnosis or a small cluster of disorders. Only recently has research begun to investigate environmental exposures in relation to quantitative dimensions that cut across traditional diagnostic boundaries.

Few risks are as potent as childhood maltreatment. Abuse and neglect confer long-lasting vulnerability to all types of emotional and somatic complaints. Keyes et al49 created a model to explain this non-specificity in the US National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). They showed that maltreatment events predicted individual differences on an internalizing spectrum that represented the commonality among interview-based anxiety and depression diagnoses. Their model also allowed for the possibility of pathways from maltreatment to the unique part of each diagnosis that was independent of all other internalizing conditions. These diagnosis-specific effects were all comparatively weak, however, leading the authors to conclude that the relationship between maltreatment and emotional complaints could be represented solely by maltreatment's link with the internalizing spectrum. Several prospective studies have corroborated this finding8, 213-216.

Adolescent stressors are often proximal triggers for first onsets of diagnosable emotional problems. Social disruption, such as peer victimization, is particularly salient during this period. Forbes et al217 hypothesized that victimization's influence on the internalizing spectrum could explain its far-reaching effects. They found that victimization experiences, such as verbal abuse and relational aggression, were robustly linked to an array of self-rated emotional problems. They observed that these various effects were almost entirely mediated by an overarching internalizing factor. Other developmental research has documented the same pattern across a number of different challenges, including romantic problems, family discord, and financial difficulty218. Moreover, it appears that differences on the internalizing spectrum predict the occurrence of future significant stressors, setting into motion a vicious cycle of stress exposure and worsening emotional problems1, 219.

Other aspects of the social milieu have demonstrated transdiagnostic effects on emotional complaints. For instance, racial discrimination is linked with a propensity to internalizing distress, but it is not specifically related to any particular type of emotional pathology220. Similarly, marital dissatisfaction is closely tied to a quantitative internalizing dimension rather than to individual forms of psychopathology85. Other parts of the social environment also tend to have stronger effects on internalizing than on its constituent diagnostic categories1.

It is not groundbreaking to find that environmental stressors are pathogenic. The key insight is that they seem to convey risk for such a broad range of emotional conditions because they operate primarily at the level of the higher-order internalizing spectrum, as opposed to specific manifestations thereof. This will not necessarily be the case across all environmental exposures, emotional phenotypes, or populations, but it is a robust trend thus far.

More research is needed to extend this paradigm to the full range of emotional dysfunction phenotypes. It is particularly important to investigate environmental variation relevant to the somatoform spectrum. Environmental events are implicated in the onset of somatoform disorders221, but there is little research on this topic from a quantitative modeling perspective. Twin, adoption and quasi-experimental designs also are needed to explicate the causal nature of observed effects.

Cognitive and affective difficulties

The internalizing spectrum is associated with cognitive difficulties that can be broadly characterized as cognitive inflexibility and behavioral disinhibition. In addition, affective difficulties – such as hyposensitivity to reward and/or hypersensitivity to punishment – appear intertwined with impaired inhibition, attentional control and decision-making, and contribute to most internalizing disorders. In general, these cognitive-affective problems likely reflect a compromised ability to inhibit intrusive and perseverative thoughts and emotions governing responses such as reward seeking and/or aversion to punishment, thereby contributing to a pattern of aberrant emotional responses and maladaptive decision-making.

Cognitive and affective difficulties are common in disorders within the distress subfactor. MDD has been linked to cognitive difficulties encompassing aspects of psychomotor speed, attention, verbal fluency, visual learning and memory, and executive functioning222-226. These problems become more severe as the disorder progresses. Similarly, PTSD is associated with temporal changes in severity of problems in attention, memory and executive functioning227, 228. PTSD is also linked with attentional bias towards trauma-related stimuli229, general inhibitory control deficits230, and attenuated reward processing231. These problems provide some evidence of reduced cognitive flexibility and behavioral disinhibition.

Cognitive and affective difficulties – which suggest cognitive inflexibility and behavioral disinhibition – are observed in all disorders within the fear subfactor, albeit to varying degrees of severity. There is evidence of mild executive functioning and memory problems in panic disorder, social phobia, specific phobias and GAD232-236, whereas difficulties found in OCD tend to be more severe236. OCD is strongly associated with reduced cognitive flexibility, as well as difficulties in other cognitive domains237-239. Unsurprisingly, anxiety-related disorders are linked to difficulties in social cognition239, 240.

Disorders within the eating pathology subfactor are characterized by difficulties with attentional inhibition, biased attention to disorder-related stimuli, and attentional set-shifting; these are common indicators of reduced cognitive and behavioral flexibility241-243 that likely underlie problems with emotional regulation and decision-making. There is additional evidence that individuals with eating disorders have compromised visuospatial ability, verbal functioning, learning and memory244. Other evidence suggests that eating disorders are associated with difficulties in integrative information processing, a cognitive perceptual-processing style termed weak central coherence245.

There are limited data related to objective measures of cognitive functioning in individuals with sexual disorders. However, there is evidence of perseverative cognitive schemas246, 247, which are likely attributable to cognitive inflexibility and/or behavioral disinhibition.

Children, adolescents and college students with general internalizing symptoms show sluggish cognitive tempo248, 249, which is linked with associated decrements in processing speed249. Internalizing is also associated with decreased cognitive flexibility in adolescents250, which is consistent with difficulties in executive functions across various internalizing subfactors.

Bipolar disorders I and II are associated with cognitive problems in attention, memory and executive functions224, 251-253. Common with the other internalizing subfactors, there is evidence that bipolar disorder II is associated with reduced inhibitory control254. In contrast to most internalizing conditions, however, bipolar disorder is associated with hypersensitivity to rewards254, 255.

Finally, few studies have explored cognitive difficulties in somatoform disorders. The available evidence suggests that the somatoform spectrum is associated with difficulties in attention and memory, and reduced attentional control in relation to threatening stimuli256, 257. The limited available data suggest that this factor is linked with behavioral disinhibition, but more research is needed.

Neural substrates: neuroimaging

Across the internalizing spectrum, the neuroimaging literature varies by subfactor and modality to include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) sequences of functionality (i.e., blood oxygen level-dependent activation, connectivity) and structure (i.e., volumetric, diffusion tensor imaging), as well as studies using nuclear imaging to reveal regional metabolic states – i.e., positron emission tomography (PET) and single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT).

This evidence indicates a range of functional disruptions (i.e., diminished or accentuated activity and connectivity) or aberrations (i.e., decreased white matter integrity and reduced volume) in neuroanatomical regions and pathways. The severity of these disruptions and aberrations is influenced by issues involving methodology, disorder comorbidity, illness phase/severity, genetics, pharmacology, and pathophysiology. Nevertheless, most studies show mild-to-moderate differences in comparison to controls or other clinical groups. Overall, the findings highlight the shared underlying neurobiology of the internalizing spectrum, which commonly includes fronto-striatal and fronto-limbic circuitry implicated in compromised self-regulation of behavior and processing of emotions in response to salient reward or punishment.

The literature on the distress subfactor is well established. Borderline personality disorder and PTSD share common neuropathological pathways, namely those included in cognitive-limbic circuitry258. MDD is associated with reduced volume of both cortical and limbic regions259. PTSD and MDD show altered activation in regions associated with cognition and emotion260, 261. PTSD is associated with alterations in white matter tracts involved in executive functions, context learning and memory, salience processing, and emotional control262. MDD and PTSD both show reduced brain volume of specific regions, with PTSD showing greater reductions overall263. In MDD, there are also significant reductions in white matter tracts involved in cognition, memory and emotion264. For GAD, there is functional and structural evidence of alterations in frontal-limbic neurocircuitry265. Overall, the findings suggest compromised fronto-limbic-striatal circuitry in this subfactor.

There is substantial evidence of compromised functioning and structural differences within the fear subfactor. Most data come from studies of OCD and social anxiety, followed by phobias, with less evidence for other fear disorders. Overall, there appears to be consistent hyperactivation of regions implicated in cognitive-emotional responses to threat266-272. Alterations in connectivity are shared between fear disorders (e.g., panic disorder and social phobia); although these might include disruptions (e.g., hypoconnectivity) within various interdependent neural networks, most often there are alterations in fronto-striatal connectivity273, 274. Alterations within the sensorimotor network are observed primarily in panic disorder. The limited structural evidence shows compromised white matter integrity, and differences in cortical and subcortical volume269, 275.

The eating pathology subfactor is characterized by compromised self-regulation and aberrant reward processing276-279. Studies show compromised connectivity and abnormal regional activation in response to reward278. There is also evidence of underlying neuroendocrine dysfunction280. In terms of structural evidence, there are inconsistencies in findings from volumetric studies and a small but growing literature indicating compromised white matter tracts281-283. Overall, findings provide evidence to implicate disrupted functioning of fronto-striatal circuits involved in cognitive-emotional control.

There is little neuroimaging research related to sexual problems. However, the handful of papers are consistent in showing altered neural activity, namely hypoactivation of areas associated with cognition, motivation and autonomic arousal, and increased activation of the self-referential network284, 285. Few studies have investigated structural differences or white matter integrity in this subfactor.

The mania subfactor is interstitial between internalizing and thought disorder, sharing a number of neural abnormalities with psychotic disorders11. However, in line with the theme observed in internalizing, bipolar disorder is associated with disrupted fronto-limbic circuitry as evidenced by altered white matter tracts and abnormal regional activation286-289.

There is evidence of structural and functional aberrations in the somatoform spectrum. Due to methodological confounds, the literature is not as strong as in areas such as distress and fear. Nevertheless, the findings suggest disruptions or alterations in the fronto-striatal-limbic network290.

Neural substrates: neurophysiology

Neurophysiological measures provide more direct indicators of neural activity that have greater temporal sensitivity. Internalizing conditions most frequently have been examined using electroencephalography (EEG), including both spectral power and event-related potentials (ERPs), which index a number of different cognitive, emotional and motivational processes.

Frontal EEG asymmetry is a relative difference in alpha power between the right and left frontal regions291, 292. Alpha activity has been shown to index inhibition of cortical activity, and lower frontal EEG asymmetry scores (right alpha minus left alpha) are posited to reflect relatively less left than right cortical activity. Frontal EEG asymmetry has primarily been interpreted via an approach-withdrawal model293, such that less relative left cortical activity is thought to reflect reduced approach motivation and increased withdrawal motivation.

The distress subfactor has demonstrated the most substantial association with frontal EEG asymmetry294, although the evidence is inconsistent295. MDD and depression symptoms have been associated with a lower relative left frontal EEG asymmetry, both at rest and during emotional and motivational tasks296-302. Panic disorder303 and OCD304 have also been associated with a lower relative left frontal EEG asymmetry. In contrast, onset of bipolar disorder is predicted by greater relative left frontal EEG asymmetry305.

The reward positivity (RewP), also known as the feedback negativity, is an ERP component reflecting reinforcement learning and reward system activation306. The RewP has demonstrated the most consistent association with the distress subfactor307, 308. MDD and depression symptoms have been associated with a more blunted RewP in both adolescents and adults309-316. GAD symptoms have also been associated with a more blunted RewP317. The RewP has been associated with risk for, and family history of, MDD318, 319, and has been shown to predict major depressive episodes, first-onset depressive disorder, and greater depression symptoms prospectively320, 321.

The error-related negativity (ERN) is an ERP component that occurs in response to an error of commission and is posited to reflect the increased need for cognitive control and threat sensitivity322. An enhanced ERN has been associated with both fear and distress subfactors323. OCD, GAD and social anxiety all have been characterized by an enhanced ERN324-330. The ERN has been associated with risk for, and family history of, OCD325, 331, 332, and has been shown to predict the development of first-onset anxiety disorders and GAD prospectively333, 334. Within the somatoform spectrum, initial evidence suggests that health anxiety is associated with an enhanced ERN335.

The P3 is a widely studied ERP component that is posited to index attentional allocation. Distress, eating and somatoform disorders all have been associated with a reduced P3336-341. These findings suggest that P3 alterations may be shared across the internalizing and somatoform spectra. Because P3 reductions have also been widely reported in psychosis and externalizing psychopathology11, 12, they may simply represent a marker of general psychopathology342. Enhanced P3, however, has also been associated with the internalizing spectrum, especially with its fear and eating pathology subfactors343-346.

The late positive potential (LPP) is a later ERP component reflecting elaborative and sustained attention toward motivationally salient stimuli. The distress subfactor has been associated with a reduced LPP to emotional stimuli347-351, whereas the fear subfactor has been associated with an enhanced LPP to aversive and unpleasant stimuli349, 352-355.

Other biomarkers

Disorders within the internalizing and somatoform spectra share several peripheral biomarkers related to stress reactivity. First, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) assessed in blood serum and plasma indexes neuronal survival, synaptic signaling, and synaptic consolidation. Meta-analyses support reduced expression of BDNF in depression, bipolar disorder, suicide behavior, and eating pathology356-361.

Second, cortisol productivity is a biomarker of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function. Increased cortisol levels have been associated with distress362-365, fear233, 366, and somatoform367 conditions. Blunted cortisol, however, has also been reported368, 369, especially in PTSD370. Mixed findings exist for eating pathology371, 372 and may be explained by the heterogeneity in sample composition and symptom severity.

Third, elevated levels of pro-inflammatory markers in peripheral tissues are evident in emotional dysfunction disorders. Meta-analyses found elevated levels of C-reactive protein, interleukin (IL)-6, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α in depression373-376; IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α and interferon (IFN)-γ in PTSD377, 378; IL-6 and TNF-α in bipolar disorder373; and IL-6 and TNF-α in anorexia nervosa379. However, there were no significant associations with bulimia nervosa379. Although it transcends diagnostic boundaries, inflammation might nonetheless be attributable to specific symptoms such as sleep problems, appetite changes, and fatigue380, 381.

Finally, the gut-brain-microbiota axis is closely linked to the stress response, and a differential abundance of gut bacterial groups has been identified in depressive, anxiety, PTSD, bipolar, eating and pain-related psychopathology382, 383. Some bacteria have been implicated across multiple conditions. For example, there is a reduction in the abundance of Faecalibacterium in patients with MDD384, bipolar disorder385, GAD386, and irritable bowel syndrome387.

Overall, peripheral biomarker studies indicate common biological signatures for disorders within the emotional dysfunction superspectrum. However, existing research is constrained by methodological limitations, including small sample sizes and a focus on a limited number of disorders. Moreover, the implicated biomarkers are also associated with other forms of psychopathology, such as schizophrenia388. Studies assessing multiple forms of psychopathology are needed to clarify the specificity versus non-specificity of these biological correlates.

Childhood temperament antecedents

Models of childhood temperament consistently highlight three dimensions that capture tendencies towards negative emotionality, approach-sociability (or surgency), and effortful control (or low impulsivity and disinhibition). These dimensions have close ties with basic traits of normative personality and maladaptive personality pathology389-392.

Given that NA/N is the core of internalizing psychopathology, it is unsurprising that negative emotionality in childhood predicts subsequent internalizing389, 393. This prospective association has been found not only for core internalizing dimensions, such as depression and anxiety symptoms, but also for eating pathology394-396 and somatic symptoms397. However, other evidence suggests that youth negative emotionality is a non-specific risk for subsequent psychopathology broadly8, particularly externalizing psychopathology398, 399.

Individual differences and behavior genetics research both suggest that low levels of approach-sociability (fearfulness, social withdrawal, behavioral avoidance) together with high levels of negative emotionality may be a combination of traits that differentiates internalizing from externalizing psychopathology397, 400, 401. Interestingly, this combination of high negative emotionality and low approach-sociability may predict anxiety, but not depression402. For example, a nationally representative cohort study of 4,983 Australian children followed from age 5 to 13 found that high negative emotionality in early childhood represented a broad risk for subsequent psychopathology, but low approach-sociability only uniquely predicted higher levels of anxiety403. This is consistent with the research finding that behavioral inhibition – a combination of negative emotionality and low approach – is a robust predictor of anxiety404, 405. By contrast, high negative emotionality and high approach-sociability (and extraversion) were found to predict subsequent purging behaviors in adolescence394, which is more consistent with patterns seen with externalizing disorders403, 406.

The third temperamental domain, (low) effortful control, appears to have an inconsistent association that is not specific to internalizing after controlling for concurrent levels of externalizing psychopathology404. Similarly, both high and low effortful control (persistence) in early childhood have been found to predict eating pathology in adolescence407, 408. This domain seems to be a more specific and robust predictor of subsequent externalizing12.

Illness course

Data from the US National Comorbidity Study Replication suggest that anxiety disorders generally have an earlier age of onset (50% by age 11) than depressive disorders (50% by age 32). However, this distinction is largely driven by disorders within the fear subfactor409-411. Age of onset for somatoform disorders appears to fall in between (50% by age 19412). Rates for both anxiety and depressive diagnoses decline in midlife (e.g., >55 years413).

Although traditionally discouraged as a diagnosis before adulthood, borderline personality disorder frequently emerges in late childhood or early adolescence414. Within eating disorders, anorexia nervosa appears to have a mean age of onset between 16 and 19 years, with bulimia nervosa slightly later between 17 and 25 years415.

Internalizing and somatoform diagnoses follow an episodic, oftentimes chronic, course. Within a hierarchical framework, there are three primary ways of conceptualizing course: homotypic (i.e., course within a single condition), heterotypic (i.e., relations between different conditions over time), and latent liability (i.e., the course exhibited by a shared underlying factor). Psychiatric research traditionally has emphasized homotypic course. For example, using the NESARC dataset, which has two waves separated by approximately three years, Lahey et al416 found moderate to strong homotypic continuity of six internalizing diagnoses (tetrachoric r = .41-.56). Bruce et al410 showed that the probability of recovery was only moderate for GAD, social phobia, and panic disorder with agoraphobia, but high for MDD and panic disorder without agoraphobia; however, risk for recurrence was high for all disorders over a 12-year span. Shea and Yen417 found that MDD showed high rates of both remission and recurrence over a two-year follow-up; in contrast, anxiety disorders had very low recovery rates, even after five years. Similar findings emerge in epidemiological samples, although more individuals appear to recover without recurrence418.

Two studies of large clinical samples found high rates of remission (85-99%) for borderline personality disorder over the course of 10-16 years, with moderate rates of relapse (10-36%)419, 420. A review suggested that anorexia and bulimia nervosa both show high remission (70-84%) over 10-16 years, with those who have not remitted often transitioning to an eating disorder not otherwise specified421.

High rates of comorbidity raise questions of how this covariation manifests across time. Heterotypic continuity frames the question of course in terms of whether a given form of psychopathology (e.g., MDD) at one point in time conduces to another (e.g., GAD) at a later point422. Lahey et al416 found that heterotypic continuity was widespread within and across internalizing and externalizing diagnoses, although somewhat stronger within spectra. In fact, heterotypic continuity was comparable in magnitude to homotypic continuity, with significant heterotypic effects persisting after adjusting for all other diagnoses. Likewise, heterotypic developmental trajectories are the rule rather than the exception across childhood and adolescence, with childhood symptoms such as emotion dysregulation and irritability considered markers of a broad vulnerability for subsequent mental illness423, 424. Relatedly, Moffitt et al425 found that neither GAD nor MDD preferentially preceded the other, and ordering effects were symmetrical. Few studies have examined the stability of somatoform disorders, but four-year stability in early adulthood was high when considering heterotypic continuity426.

Given this widespread heterotypic continuity, it becomes important to chart the course of the shared liability attributable to the higher-order spectra. In early adulthood (ages 18-25), longitudinal continuity among diagnoses was best accounted for by the stability of a general internalizing factor427. The same appears true in later adulthood, as latent internalizing factors were significantly correlated between age 41 and ages 56 (r=.51) and 61 (r=.43); these associations could largely be explained by genetic factors428. Relatedly, the substantial heterotypic continuity of depression and anxiety symptoms, and of different eating pathology symptoms, was largely attributable to stable, common genetic influences173, 429, 430. Finally, Wright et al431 found that an interview-assessed, disorder-based internalizing factor strongly predicted a symptom-based internalizing factor (beta=.60) assessed via daily diary 1.4 years later. Overall, the evidence suggests that spectra represent the primary pathways of illness course, and constitute liabilities for the development of multiple conditions across the lifespan.

Treatment response

Given the high rates of comorbidity and the ubiquitously positive treatment response to cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) across various internalizing disorders432-434, there has been a focus on testing treatments that were designed to be transdiagnostic (i.e., target multiple disorders). Meta-analyses of transdiagnostic theory-based CBT protocols for internalizing have demonstrated medium to large effect sizes for anxiety and depression, that were maintained at post-treatment follow-up432-435. There are particularly large effects for CBT in youth when parents are more involved in treatment436.

Findings indicate no significant differences between transdiagnostic CBT and disorder-specific CBT protocols, which supports the efficacy of transdiagnostic CBT for internalizing434, 435. Moreover, although there has been concern about including certain diagnoses (e.g., OCD and PTSD) in transdiagnostic CBT treatments, Norton et al437 showed that transdiagnostic treatments for DSM-IV anxiety disorders were not associated with differential outcome by diagnosis.

Similar to transdiagnostic CBT, the unified protocol (UP) for the transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders was specifically designed to target co-occurring internalizing disorders438, 439. Studies show that the UP is equivalent in effectiveness to gold-standard treatments designed to target single disorders438, 440. The UP is much more efficient than single-disorder treatments, because clinicians only need to learn one protocol to treat internalizing disorders. Preliminary efficacy data show that, across diagnostic categories, the UP results in significant improvements in daily functioning, mood, depression, anxiety, and sexual functioning441-444. Treatment benefits from the UP were maintained at 6- to 12-month follow-up443-445. Transdiagnostic interventions are now being extended to flexible modular protocols in adults446, mirroring efficacious modular transdiagnostic treatments across the internalizing spectrum in youth447.

Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) is efficacious for treating certain internalizing disorders, such as depression and bulimia nervosa448, 449, although results were less pronounced and slower to emerge for the latter condition449. One review indicated that IPT was superior to CBT in treating depression448. Variants of IPT, including interpersonal social rhythm therapies (IPSRT), are beneficial as acute and maintenance treatments for both unipolar and bipolar depression450-452, but have not been studied extensively in other forms of internalizing. Thus, there is support of IPT as a treatment for some, but not all, forms of internalizing, with the majority of research showing that it may be a useful treatment for distress and eating disorders, with limited efficacy for fear-based disorders, such as social phobia453.

The limited available evidence indicates that treatments used for internalizing disorders (i.e., CBT and antidepressants) also are efficacious for somatic symptom disorders221, 454. Although findings are mixed, CBT has been found to have lasting benefits for up to 12 months post-treatment455-458.

Turning to pharmacological treatments, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are efficacious for the treatment of several internalizing disorders compared to placebo459, 460; however, SSRIs are associated with an increased risk for sexual dysfunction93. Meta-analyses showed that atypical antipsychotics were significantly more efficacious for treating unipolar and bipolar depression and PTSD compared to placebo461-464. Another meta-analysis of off-label uses of antipsychotics found that quetiapine resulted in significant improvements in GAD symptoms, whereas risperidone significantly reduced OCD symptoms465. A large clinical trial found that olanzapine significantly increased weight gain in the treatment of anorexia nervosa compared to placebo466. However, atypical antipsychotics had limited benefits for improving quality of life in people with depression467 and did not impact psychological symptoms in individuals with anorexia nervosa466. Overall, substantial data indicate that SSRIs and SNRIs are beneficial for treating most internalizing conditions, with accumulating evidence that atypical antipsychotics may be useful adjunctive medications. The available evidence for the efficacy of pharmacological treatments for somatoform disorders appears mixed and of low quality468.

Summary of validity evidence

Table 3 summarizes the validity evidence reviewed in previous sections. It is noteworthy that virtually all associations are transdiagnostic in nature. That is, the studied variables are not simply related to a single form of psychopathology, but rather are associated with multiple conditions within the emotional dysfunction superspectrum (and, in many cases, to other forms of psychopathology as well). Studies have shown that multiple dimensions falling within the superspectrum share genetic diatheses, environmental risk factors (e.g., childhood maltreatment, financial difficulty, racial discrimination), cognitive and affective deficits (e.g., cognitive inflexibility, behavioral disinhibition), neural substrates (e.g., impaired fronto-striatal and fronto-limbic circuitry, blunted RewP, enhanced ERN) and other biomarkers (e.g., pro-inflammatory markers), as well as childhood temperamental antecedents (e.g., high negative emotionality, low surgency). Not surprisingly, therefore, dimensions within this spectrum respond to the same transdiagnostic treatments (including CBT and SSRIs) and are substantially related to one another both concurrently and prospectively.

| Somatoform | Internalizing | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Distress | Fear | Sexual problems | Eating pathology | Mania | ||

| Genetics | |||||||

| Family/twin heritability | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | |

| Molecular genetics | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | |

| Environment | |||||||

| Childhood maltreatment | +++ | ||||||

| Adolescent stressors | + | +++ | |||||

| Racial discrimination | +++ | ||||||

| Relationship satisfaction | +++ | ||||||

| Cognition | |||||||

| Cognitive deficits | + | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ |

| Affective deficits | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | + |

| Neurobiology | |||||||

| Structural | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | |

| Functional | |||||||

| Neuroimaging | + | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | +++ | ++ |

| Electrophysiology | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | + | + | |

| Biomarkers | |||||||

| Reduced BDNF expression | + | +++ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | |

| Cortisol alterations | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ |

| Pro-inflammatory markers | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ |

| Gut-brain microbiota | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | |

| Antecedents/Course | |||||||

| High negative affectivity | + | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | +++ | |

| Low approach-sociability | +++ | ++ | – | ||||

| Low effortful control | + | ||||||

| Age of onset | + | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ||

| Chronicity/stability | + | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ||

| Treatment | |||||||

| Response to CBT | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | ||

| Response to UP | +++ | ++ | ++ | + | |||

| Response to IPT | ++ | ++ | + | +++ | + | ||

| Response to SSRIs | + | +++ | +++ | +++ | – | +++ | |

| Response to SNRIs | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ||

| Response to atypical antipsychotics | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | ||

- +: some evidence for effect, ++: some replications, +++: repeatedly replicated finding, –: effect in the opposite direction, BDNF – brain-derived neurotrophic factor, CBT – cognitive behavior therapy, UP – unified protocol, IPT – interpersonal psychotherapy, SSRIs – selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, SNRIs – serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors. Subfactors with ambiguous or inconsistent structural placement (in this case, mania) are italicized.

These validity data are quite congruent with the structural evidence reviewed earlier. That is, many variables are related to both internalizing and somatoform conditions, and these shared factors can be captured by the emotional dysfunction superspectrum; other variables are more clearly linked to one spectrum than the other, thereby accounting for their emergence as distinct spectra at a lower level of the hierarchy. Similarly, some variables show relatively non-specific associations with all major forms of internalizing, which helps to account for its coherence as a structural dimension; in contrast, other variables show stronger links to some types of internalizing than to others, consistent with the emergence of distinct subfactors within internalizing.

Two caveats are important to mention. First, several validators were also linked to other spectra (e.g., the psychosis superspectrum also responds to antipsychotics, the externalizing superspectrum also shows high childhood maltreatment, and all three superspectra are positively associated with pro-inflammatory markers)11, 12, such that the specificity of these associations is uncertain. Second, some internalizing conditions show a distinct profile on certain validators, which underscores the value of the lower levels of the HiTOP hierarchy. Mania, in particular, is distinct with regard to genetic liability, affective deficits, and episodic course.

UTILITY EVIDENCE

The internalizing and somatoform spectra show greater utility than traditional diagnoses with respect to reliability, explanatory power, and clinical utility.

As discussed earlier, the reliability of emotional dysfunction diagnoses tends to be unimpressive. The DSM-5 field trials found that interrater reliability (kappa coefficient) ranged from .20 (GAD) and .28 (MDD) to .61 (complex somatic symptom disorder) and .67 (PTSD)25. In these field trials, patients used a 5-point scale to report key symptoms of depression, anxiety, sleep, suicide, and somatic distress. Dimensional assessment substantially improved reliability for individual symptoms, with retest correlations ranging from .64 to .78 (mean=.70); symptom composites were even more reliable27. This underscores a consistent pattern that dimensional descriptions of psychopathology are more reliable than categories. Of note, some studies – such as a field study of ICD-11 diagnoses469 – reported higher interrater reliabilities for diagnoses, but they used less stringent designs that may inflate reliability estimates23.

In longitudinal studies, latent internalizing spectra have shown high long-term stability in childhood (test-retest r=.85 over 3 years)62, young adulthood (r=.69 over 3 years)45, and middle adulthood (r=.74 over 9 years)470. Likewise, the distress and fear subfactors showed impressive stability over two months (r = .81 and .87, respectively)80, one year (r = .85 and .89)86, and three years (r = .60 and .64)73. Comparable data are not available for other conditions within the superspectrum. Overall, a meta-analysis estimated the reliability of internalizing dimensions to be .82, a substantial improvement over categorical diagnoses22.

The ability to explain functional impairments, risk factors, outcomes and treatment response is an essential feature of diagnostic utility. A meta-analysis found substantially higher explanatory power for internalizing dimensions (mean correlation r=.51) than categories (mean r=.32) across multiple validators22. Several studies directly compared HiTOP-consistent and DSM descriptions of internalizing psychopathology, finding that HiTOP dimensions explained twice as much variance in functional impairment471 and the probability of antidepressant prescription472. Also, compared to DSM diagnoses, HiTOP dimensions explained six times more variance in impairment related to eating pathology88, and predicted two times more variance in clinical outcomes 6-12 months later473. Thus, the HiTOP characterization of internalizing problems can substantially increase clinical utility.

The clinical utility of a nosology encompasses additional considerations, such as facilitating case conceptualization, communication with professionals and consumers, treatment selection, and improvement of treatment outcomes474, 475. Existing research is limited by reliance on practitioner ratings, global evaluation of a system rather than individual spectra or disorder classes, and primary focus on personality disorders. Nevertheless, recent research consistently indicated that practitioners give higher ratings to dimensional descriptions than categorical diagnoses on most utility indicators476-479. In the DSM-5 field trials, dimensional measures were rated positively by 80% of clinicians480. Nevertheless, it is important to investigate the clinical utility of the internalizing and somatoform spectra specifically, and to study objective criteria of clinical utility, such as measured improvement in treatment outcomes.

The clinical acceptability of HiTOP is unsurprising, as it is grounded in an established practice of conceptualizing patients according to symptom and trait dimensions. The HiTOP advances this practice by providing a rigorous system of dimensions and validated tools to assess them. It also recognizes the need for categorical decisions (e.g., to treat or wait) in clinical practice481. Multiple ranges of scores (e.g., none, mild, moderate and severe psychopathology) have been identified to support clinical decisions. The HiTOP consortium is developing additional ranges for specific clinical questions (e.g., indication for suicide prevention) using strategies that were established in other fields of medicine for optimal categorization of dimensional measures482, 483.

In this, the HiTOP builds on a strong foundation of research and practice. Dimensional measures of emotional dysfunction are among the most widely used instruments in psychiatry, including the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression484, the Beck Depression Inventory485, the Beck Anxiety Inventory486, the Patient Health Questionnaire487, and the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale488. However, such measures were developed to assess specific clinical conditions and none covers the internalizing or somatoform spectra comprehensively.

MEASUREMENT

Several broad symptom measures have been created to assess multiple higher- and lower-order internalizing dimensions. The original and expanded forms of the Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms (IDAS and IDAS-II, respectively) contain self-report scales assessing symptoms of depression, anxiety, PTSD, OCD and mania100, 489. The IDAS-II scales index the HiTOP-consistent factors of distress, obsessions/fear, and positive mood/mania, with high internal consistency and stability over short intervals100. The Interview for Mood and Anxiety Symptoms targets dimensions similar to the IDAS-II, but with an interview format to capture the strengths of clinician-based assessment80, 471, 490. These instruments can be supplemented with the self-rated90 and clinician-rated491 versions of the Eating Pathology Symptoms Inventory, which provide comprehensive assessment of eating disorder symptoms. Widely used measures of sexual functioning are problematic492, indicating a need for better assessment.

Omnibus personality inventories have demonstrated strong overlap with symptom measures of internalizing105, 493. The Personality Inventory for DSM-5 (PID-5)494, the Schedule for Nonadaptive and Adaptive Personality495, and the Dimensional Assessment of Personality Pathology - Basic Questionnaire496 all contain personality trait facets (e.g., depressivity, emotional lability) that index the higher-order NA/N domain. The PID-5 specifically matches the DSM-5 alternative model of personality disorders as well as the proposed five ICD-11 trait domains494, 497, 498. The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2-Restructured form (MMPI-2-RF)499 and the Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI)500 both provide clinical measurement (with population representative norms) of the internalizing and somatoform spectra, with well-validated scales that capture the higher-order level (e.g., MMPI-2-RF emotional/internalizing dysfunction and somatic complaints) and much of the lower-order level (e.g., MMPI-2-RF: low positive emotions, stress/worry, anxiety, malaise, neurological complains; PAI: depression-cognitive, anxiety-physiological, somatic conversion)2, 501, 502.

Evidence for a distinct somatoform spectrum47, 103, 105 indicates the need to measure somatization symptoms in detail. A systematic review of self-report questionnaires for common somatic symptoms has identified a total of 40 measures, with the majority deemed unsuitable for future use503. The authors concluded, however, that the Patient Health Questionnaire-15504 and the Symptom Checklist-90 Somatization Scale505 were the most suitable scales, given their validity, internal consistency, content coverage, replicable structure, and short-term stability503. The Bodily Distress Scale (BDS)108 is a more recent measure of the bodily distress syndrome118, 119, which encompasses a large range of somatoform facets. None of these measures cover health anxiety, however, which can be assessed using the Whiteley Index506 or the more comprehensive Multidimensional Inventory of Hypochondriacal Traits120.

RESEARCH IMPLICATIONS