The role of indigenous healers in treating surgical conditions in the rural Eastern Cape of South Africa

Neha Sangana and Paolo Rodi have contributed equally as the co-first authors.

Abstract

Background

Indigenous knowledge healers (IKHs) provide alternative healthcare to formal health services in rural South Africa, but there is a gap in knowledge regarding their treatment of surgical conditions. This study evaluated IKH surgical care and described their perspective of the dual health system.

Methods

A cross sectional survey of IKHs in the Madwaleni Hospital catchment of the Eastern Cape, South Africa was conducted. Topics included the training and experience of IKHs, treatment of nine common surgical conditions, referral patterns, disease origin beliefs, benefits and limitations of care, and collaborative opportunities between the two health systems.

Results

Thirty-five IKHs completed the survey. IKHs were consulted by persons with all nine surgical conditions. The most common forms of treatment were application of an ointment on the affected site (88%) and oral medication (82%). Operative treatment was only done for abscess. Referrals to the formal healthcare sector were made for all surgical conditions. IKHs reported that they were limited by their lack of training and resources to perform operations. On the other hand, they perceived the treatment of the spiritual aspect of surgical disease as a benefit of their care. Thirty-five (100%) IKHs were interested in closer collaboration with the formal health sector.

Conclusion

IKHs treat surgical conditions but refer to the formal health sector when diagnostic and operative services are needed. More research is needed to determine the potential advantages and disadvantages between the formal health sector and IKH collaboration.

1 INTRODUCTION

In rural South Africa, there is poor access to surgical care, despite a high burden of surgical conditions, especially traumatic injuries, requiring quality operative care delivered in a timely manner.1, 2 An individual's journey to care begins with their decision to seek care and is influenced by personal beliefs regarding disease origin, health literacy, and beliefs in parallel health systems.3, 4

Up to 80% of South Africans seek healthcare in the indigenous health system through consultation with indigenous knowledge healers (IKHs), also known as traditional health practitioners.5, 6 Their healing practices are derived from traditional values and belief systems.7 There are estimated to be 200,000 IKHs in South Africa. One of the most rural provinces, the Eastern Cape, has an estimated 50,000 IKHs, amounting to more than the number of registered physicians.8 Previous studies have demonstrated that individuals may seek care with IKHs due to increased accessibility and aligning beliefs around health and well-being.5, 7

IKHs in South Africa treat burns and septic wounds.9, 10 In other countries, IKHs also treat cancer and fractures.7, 11-14 Given the prevalence of IKHs in South Africa, it is possible that they may see people with a wide range of surgical conditions. There is a gap in literature identifying their scope of surgical practice.

The aim of this study was to explore surgical treatment by IKHs and to identify barriers and facilitators to IKHs working with the formal health sector in the rural Eastern Cape. These results will contribute to strategies to improve care for persons with surgical conditions in South Africa.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study site and population

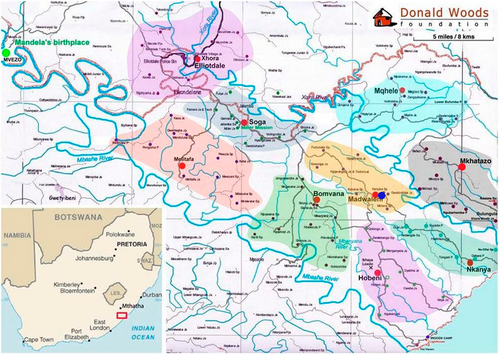

The study was conducted in the Madwaleni Hospital catchment (population of approximately 130,000) in the Mbhashe municipality of the Amathole District of the Eastern Cape Province covering an area of 1200 km2. Madwaleni is a district hospital and receives patients from nine primary health clinics located in distinct villages (Figure 1). The predominant cultural group in the area is the AmaBomvana of the amaXhosa people. For the AmaBomvana, well-being entails a healthy spiritual relationship with the ancestors and the environment. Their beliefs include a parallel dimension inhabited by ancestral spirits who safeguard the health of their descendants from malevolent spirits.15

Map of Madwaleni area with nine health districts presented as red dots and Madwaleni District Hospital presented as a blue dot.

There are approximately 50 IKHs working in the Madwaleni catchment. These practitioners are revered for their ability to communicate with the ancestors and report that their knowledge of curative medicines is obtained directly from the ancestors, often through revelatory dreams. At a young age, they receive a calling to pursue healing through such dreams. They undergo training via apprenticeships, personal research, and further revelatory dreams from the ancestors.16

2.2 Study design and sampling

This was a cross-sectional survey done over 6 weeks in 2023. Purposive and snowball sampling were used to recruit IKHs working in the Madwaleni area. The participants were invited via phone call and the interviews were conducted face-to-face. There was no minimum sample size and as many IKHs as possible from the area were recruited although at least 2 from each of the nine health clinic catchments were solicited.

The survey (Supporting Information S1: Appendix 1) was created after initial qualitative exploration with three IKHs from the study area. The final survey tool included 19 questions which contained yes/no questions (regarding surgical conditions treated), multiple choice plus a fill-in option (regarding treatment type), and four open-ended questions (regarding ancestral gifts/powers and working with the formal health sector). The survey tool was translated into isiXhosa, the dominant language spoken in the area, and piloted for feasibility and acceptability. After appropriate training, research assistants administered the survey in isiXhosa with the help of local translators. Responses were translated and transcribed in English.

2.3 Ethics

Ethical approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee at Stellenbosch University (HREC Reference No.: N22/09/109). Local traditional chiefs were sensitized to the survey and their permission was obtained to conduct the study. Prior to participation, IKH participants were consented and explained the risks and benefits of the study.

2.4 Data analysis

Survey responses were recorded on paper forms and entered into a Google Form™. Weekly audits were done to ensure accuracy of data transfer. There was no minimum sample size since no inferential statistics were used. Quantitative descriptive analysis was done through counts and percentages. Some open-ended responses were used verbatim for illustrative purposes.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Demographics

Thirty-six IKHs were recruited and 35 (97%) completed the survey. The median age was 59 (IQR = 47–71) years and 14 (40%) were female. Training and skills were acquired via several overlapping practices including apprenticeships, revelatory dreams from the ancestors, and personal research (Table 1).

| Origin of knowledge | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Direct teaching from ancestors | 33 (94) |

| Apprenticeship with more experience healers | 29 (83) |

| Self-taught | 13 (37) |

| “Gifts” received by the ancestors | |

| I can predict the future | 32 (91) |

| I can interpret dreams | 35 (100) |

| I can communicate with ancestors | 35 (100) |

| I can perceive the same feelings as the patient | 31 (89) |

| I can use medicinal plants | 35 (100) |

| I can protect from evil spells | 32 (91) |

| I can practice magic | 3 (9) |

| I can see evil spirits | 1 (3) |

| No gifts | 0 (0) |

3.2 Surgical conditions treated

The nine surgical conditions were treated by 11–27 (31%–77%) IKHs. Abscess was the most frequently treated surgical condition (n = 27 and 77%) followed by burns (n = 25 and 71%) (Table 2).

| Condition | IKHs treating conditiona | Ointments | Oral medication | Wound care and splinting | Operation | Referral to hospital |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%)b | n (%)b | n (%)b | n (%)b | n (%)b | |

| Abscess | 27 (77) | 26 (96) | 20 (74) | 0 (0) | 9 (33) | 8 (30) |

| Burn | 25 (71) | 25 (100) | 14 (56) | 23 (92) | 0 (0) | 16 (64) |

| Infected wound | 24 (69) | 24 (100) | 19 (79) | 23 (96) | 0 (0) | 15 (63) |

| Laceration | 22 (63) | 20 (91) | 15 (70) | 10 (44) | 0 (0) | 12 (57) |

| Fracture | 17 (49) | 8 (44) | 16 (94) | 10 (61) | 0 (0) | 17 (100) |

| Gangrene | 16 (46) | 16 (100) | 14 (88) | 13 (81) | 0 (0) | 11 (69) |

| Umbilical hernia | 16 (46) | 16 (100) | 14 (88) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 10 (65) |

| Breast lump | 15 (43) | 11 (73) | 14 (93) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 10 (67) |

| Thyroid goiter | 11 (31) | 9 (83) | 10 (92) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 7 (67) |

- a Out of 35.

- b Out of IKHs treating the condition.

3.3 Disease origin

Treatment type was related to the perceived mechanism of the condition. Conditions perceived by some healers to be incurred by external mechanisms were laceration, abscess, and infected wounds. These were primarily treated with ointment. Conditions described as having internal mechanisms of disease or injury, such as fracture, breast lump, and thyroid goiter, were more commonly treated with oral medication and more commonly referred to the hospital.

Thirty-two (91%) IKHs surveyed believed that there was a relationship between the spiritual and ancestral realm and surgical conditions. The ancestors were described to be protectors of health and wellbeing who repel evil spirits seeking to do harm. Illness, injury, and surgical conditions were incurred by evil spirits and bad luck, especially when one failed to pay respects to their ancestors. In addition to condition-specific treatment, regular ceremony or sacrifice led by IKHs served to appease the ancestors. Additionally, IKHs described that prior to undertaking operative procedures in the formal health sector, people came to them to perform protective rituals invoking the ancestors.

3.4 Treatment methods

Abscess was the only condition treated with surgical incision by 9 (26%) IKHs (Table 2). Thirty-one (88%) IKHs used ointments which consisted of plant-based pastes made from local herbs and soil. Twenty-nine (82%) IKHs utilized oral medication which included homemade liquid tonics or oral powders.

3.5 Referrals

Referrals to the formal sector were made for all nine surgical conditions. IKHs perceived the formal health sector to play an important but not exclusive management role, such as in the case of fracture. All 17 (100%) IKHs who treated fractures referred them to the formal sector (Table 2). Reasons for the referral of fractures included x-ray confirmation and possible immobilization through casting, which could only be provided at a health facility. However, IKHs reported that fracture patients returned to them afterward to receive oral medications that would aid with the healing process (Table 2). For the other surgical conditions, participants described referring individuals to the formal health sector when they felt their knowledge and skills were insufficient.

3.6 Perceived benefits and limitations of each health system

IKHs reported benefits and limitations to seeking surgical care within the indigenous and formal health sectors. Focus on the spiritual aspect of care was a unique benefit of the indigenous health sector (n = 33 and 94%). Thirty-one (85%) IKHs reported persons with surgical conditions first came to them because they offered a closer personal relationship than formal healthcare staff could provide (Table 3). They said that individuals in their community were “like family” and felt understood due to the lack of language barrier and shared spiritual beliefs.

| Indigenous health sector | n (%) | Formal health sector | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benefits | Payment without money | 34 (97) | Access to operative intervention | 35 (100) |

| Spiritual aspect treated | 33 (94) | Access to anesthesia provided | 34 (97) | |

| Proximity to home | 32 (88) | Less expensive than indigenous health sector | 29 (81) | |

| Closer personal relationship | 31 (85) | Access to more medicine | 28 (78) | |

| Short waiting times | 26 (79) | |||

| No language barrier | 22 (63) | |||

| Limitations | Lack of access to operative equipment | 35 (100) | Lack of focus on spiritual aspect | 34 (97) |

| Inability to perform operations | 35 (100) | Distance from home | 33 (94) | |

| Lack of knowledge to treat | 33 (94) | Long waiting times | 32 (88) | |

| Lack of access to anesthesia | 32 (92) | Money payment required | 29 (81) | |

| Lack of medications | 32 (92) | Lack of patient–doctor relationship | 25 (69) | |

| More expensive than formal health sector | 27 (75) | Language barrier | 24 (69) |

Additionally, 34 (97%) IKHs cited that they could be paid with goods exchange and without monetary transaction. Whereas, 29 (81%) IKHs reported that direct medical costs of formal healthcare were lower than the cost of IKH care and indirect costs, such as transport and sustenance, increased the financial burden of hospital admission. Thirty-two (88%) cited proximity to their clients as a benefit of IKH care (Table 3). The lack of operative intervention was the most cited limitation of IKH surgical care (n = 35 and 100%).

Accordingly, operative intervention was the most cited benefit of the formal health sector (n = 35 and 100%). Access to medical resources, such as anesthesia (n = 34 and 97%), was the second most cited benefit of the formal health sector (Table 3). These were reported in the open-ended questions to be major reasons for referring individuals with surgical conditions into the formal health sector.

The most cited limitations of the formal health sector included the lack of focus on the spiritual aspect of surgical care (n = 34 and 97%), distance from home (n = 33 and 94%), and long waiting times (n = 32 and 88%) (Table 3). These areas were reported as benefits of the indigenous health sector.

3.7 Working with the formal health sector

IKHs shared their perspectives of working with the formal health sector. Five (14%) IKHs felt a lack of respect and recognition from health facilities. One IKH lamented that “doctors and nurses do not work with traditional healers and often complain if the patient sees a healer.” Eighteen (51%) recommended workshops or meetings between both sectors to open lines of communication and encourage understanding between the two groups (Table 4).

| Barriers | n (%) | Facilitators | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lack of respect and recognition of IKHs | 5 (14) | Workshops and meetings between IKHs and healthcare workers | 18 (51) |

| Lack of feedback to IKHs after referring individuals | 5 (14) | Formal referral system between formal and indigenous health sector | 17 (49) |

| Conflict among IKHs | 1 (3) | Having healers present at the hospital | 6 (17) |

- Abbreviation: IKHs, indigenous knowledge healers.

They noted that the relationship between the two sectors is currently one-sided, and that since they “never hesitate to send patients to health facilities for pertinent conditions… doctors should do the same for conditions better served by traditional medicine.” Seventeen (49%) IKHs expressed a desire for a formal referral system going both ways between IKHs and health facilities. Six (17%) even suggested having healers present at the hospital. Five (14%) IKHs also expressed frustration over the lack of counter referral after referring individuals to health facilities, and that they “don't know what happens after they leave to go to the hospital” (Table 4).

Lastly, 1 (3%) IKH noted that internal conflicts among the IKHs must be resolved before attempting any collaboration with the formal health sector (Table 4).

Despite these reported challenges, 35 (100%) IKHs expressed their interest in working with the formal health sector.

4 DISCUSSION

Surgical conditions are treated by IKHs in a rural province in South Africa. Treatment for these conditions is largely nonoperative, involving ointment and oral medication. IKHs reported unique benefits to their treatment for surgical conditions that may motivate individuals to seek care with them before the formal health sector. Contributing factors to this health seeking behavior include better accessibility, close personal relationships with individuals, and culturally contextualized care. The expense and difficulty of transportation to the formal health sector, combined with the relative proximity of IKHs renders them accessible to rural persons. IKHs are closely embedded in the community and social hierarchy, with personal relationships reinforcing an individual's self-value and agency and improving care.17 Surgical providers of the formal health sector may lack focus on the spiritual aspect of the disease, which is relevant to the amaXhosa people.18 IKHs provide a treatment framework focused on spirituality that allows individuals through rituals and intercession of the ancestors, to rebalance the personal relationships and spirituality believed to be the cause of illness.7, 11, 19, 20 In addition, IKHs report that they help patients better understand their experience with their illness, which promotes mental well-being.

IKHs recognized their limitations and made referrals to the formal health sector for diagnosis and treatment of surgical conditions, particularly for radiographic confirmation of fractures, care beyond their knowledge, and operative intervention. Some conditions, such as gangrene and thyroid goiter, were referred to the formal health sector because IKHs considered these conditions beyond the scope of their care. For fractures, individuals were referred to health facilities for radiography and immobilization, then returned to IKHs for oral medications to accelerate bone healing. No operations were done by IKHs except for abscess incision and drainage. IKHs have demonstrated a willingness to refer their surgical patients into the formal health sector but have reported a lack of a referral mechanism.

Previous studies have cited bilateral collaboration between indigenous and formal health sectors as a tool to potentially increase access to care.21, 22 Although many South African IKH treatments are not evidence-based and any benefit still has to be scientifically proven, our results highlight the willingness of IKHs as relevant stakeholders in promoting access to surgical care, especially at the primary healthcare level, aligning with the commitment of the 2019 UN Political Declaration on Universal Health Coverage to “explore ways to integrate […] safe and evidence-based traditional and complementary medicine services within national and/or subnational health systems.”23 There is already ongoing legislation to formally recognize IKHs as a health cadre by the Health Professional Council of South Africa IKH which could facilitate intersectoral referrals and reduce delays to operative care.23, 24

Seeking care with IKHs has been reported as a delay to seeking care in the formal health sector. However, according to some studies, bilateral collaboration might integrate the two health systems rather than isolate them,25-27 as individuals do not always recognize that they have surgical conditions which is a barrier to timely delivery of quality surgical care.18 Since IKHs are already seeing and identifying persons with surgical conditions, they might provide health education, diagnose, or refer to the formal health sector to increase access and mitigate delays and further research on this topic is needed. Nevertheless, previous studies are promising, as integration of both sectors have improved healthcare access in several Sub-Saharan African countries for human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, epidemics such as Ebola, and some surgical conditions such as septic wounds and cancer.5, 28-31

Solutions to increase access to surgical care will need to include qualitative research that includes perspectives of community members and formal health sector cadres including community health workers, clinic nurses, and surgeons. Reasons for seeking indigenous care for breast cancer reported by patients in Ethiopia and Malaysia included increased perceived safety and effectiveness of the IKH treatment and mistrust of the formal health sector.28, 32

4.1 Limitations

Participants were limited to one rural area in South Africa, so the results may not be generalizable to all of South Africa or to other countries. This study also only focused on nine surgical conditions and not all. Since research assistants did not speak isiXhosa, it is possible that nuances may have been lost in translation. This was mitigated by having an isiXhosa speaking translator who was also familiar with the survey instrument. Lastly, the only stakeholder group surveyed was the IKHs and their responses do not reflect the opinions of formal health sector providers or community members. The reported benefits of their treatment may be biased or overstated.

5 CONCLUSION

IKHs treat surgical conditions, but largely without operative intervention. Topical and oral medication are their primary methods of treatment. IKHs frequently refer individuals with surgical conditions to the formal health sector. This study contributes to the literature on the IKHs perspective on surgical care in rural South Africa. With thousands of active IKHs in South Africa and a significant reliance on traditional medicine in rural areas, more research is needed to determine the potential advantages and disadvantages of formal health sector and IKHs collaboration.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Neha Sangana: Data curation; formal analysis; investigation; project administration; validation; visualization; writing—original draft; writing—review & editing. Paolo Rodi: Formal analysis; investigation; methodology; project administration; writing—original draft; writing—review & editing. Ntombekhaya Tshabalala: Conceptualization; methodology; project administration; resources; supervision; writing—review & editing. Ethan Bell: Data curation; formal analysis; investigation; writing—review & editing. Patheka Mhlatyelwa: Investigation; project administration; resources; writing—review & editing. Andrew Miller: Conceptualization; methodology; project administration; resources; writing—review & editing. Gubela Mji: Conceptualization; methodology; resources; writing—review & editing. Kathryn Chu: Conceptualization; funding acquisition; investigation; methodology; project administration; resources; supervision; validation; writing—original draft; writing—review & editing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the Khaya Youth and Imijeloyophuhliso Foundations and Mr. Bafana Tonga, an IKH leader in the Madwaleni area, for their assistance in coordinating this study as well as all the IKHs study participants. This study was funded by the Center for Global Surgery, Stellenbosch University Center for Global Surgery, Department for Global Health, and University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Ethical approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee at Stellenbosch University (N22/09/109).

INFORMED CONSENT

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Biography

Neha Sangana was raised in Austin, Texas. She received her degree in mechanical engineering from the Johns Hopkins University and is currently obtaining her medical degree at the University of Texas at Southwestern with a distinction in Global Health. She is passionate about general surgery and improving access to surgical care. She aims to pursue these interests through a career in global surgery. Outside of medicine, she is a star-gazing enthusiast, amateur bicycle mechanic, and avid soccer fan.