The impact of colectomy on the course of extraintestinal manifestations in Swiss inflammatory bowel disease cohort study patients

Abstract

Background and Aims

Extraintestinal manifestations are reported to occur in up to 45% of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients during the course of disease. It is unknown whether colectomy reduces the rate of de novo extraintestinal manifestations (EIMs) or impacts on severity of EIMs following a parallel versus independent disease course from underlying IBD.

Methods

Using data from the Swiss Inflammatory Bowel Disease Cohort Study we aimed to analyse the course of EIMs in ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) patients undergoing colectomy during the cohort’s prospective follow-up.

Results

One hundred and twenty-one IBD patients (33 CD, 81 UC and seven unclassified) underwent colectomy during prospective follow-up in the Swiss Inflammatory Bowel Disease Cohort Study. Within the 114 patients with UC or CD any EIM was reported in 40 (nine CD and 31 UC) patients. Activity of EIMs ceased entirely after colectomy in 21 patients (52.5%). Complete cessation of EIM after colectomy was higher in patients with UC versus CD with 58.1% versus 33.3%. After colectomy, 29 out of the 114 patients (25.4%) experienced any EIM. Two thirds of these (19 patients) represented persisting EIMs, while in one third (10 patients) EIM represented a de-novo event after colectomy. Overall, 13.5% of IBD patients developed a de-novo EIM after colectomy.

Conclusions

In IBD patients undergoing colectomy, EIMs present prior to surgery will persist in about half of patients. Complete cessation of EIM after colectomy may be less common in CD than in UC. In patients who never experienced EIMs prior to colectomy de-novo manifestations thereafter should be expected in up to one in seven patients.

INTRODUCTION

Of the two main forms of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), ulcerative colitis (UC) appears to be slightly more common than Crohn’s disease (CD) and the incidence and prevalence of both conditions was reported to be rising in the western world and developing countries as well as Asia.1-3 In recent years, the treatment of IBD has progressively increased in complexity with a substantial increase in available medical treatment options. This increase in available mechanisms of action for the treatment of UC and CD has been associated with a reduced frequency of colectomy, traditionally considered the last treatment option in refractory UC. In the 1990s the fraction of UC patients undergoing colectomy within 10 years after diagnosis ranged between 20% and 45%, but dropped to less than 10% according to recent studies from Europe4-6 and North America.7

In contrast to UC, where total proctocolectomy represents the surgical strategy of choice, numerous surgical techniques for CD are available, depending on segmental intestinal involvement, extension of disease, presence of local penetrating complications as well as the surgeon’s or patient’s preference.8, 9 Due to better functional results of segmental colectomy,10 total colectomy in CD is reserved for extensive colonic involvement including a large proportion of the colon and the rectum or severe to fulminant disease activity.8, 11

In a considerable fraction of IBD patients the disease is not limited to the colon and/or small bowel but also affects other organ systems including joints, skin, liver and eyes, subsumed under the term extraintestinal manifestations (EIMs). Between 10% and 45%12-14 of IBD patients suffer from EIM, mostly arthropathies, but also aphthous stomatitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), uveitis, erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum. Currently, knowledge on the pathogenesis of EIM remains limited.15, 16 In around a quarter of patients EIM manifest before diagnosis of IBD,17 whereas in others first presentation of EIM follows IBD diagnosis by several years.18 The clinical course of some EIM, for example, pauciarticular peripheral arthritis14 (type I), was reported to follow a course of disease largely parallel to the disease activity of the underlying IBD, in contrast to others, such as PSC, ankylosing spondylitis or polyarticular arthritis14 (type II), with a rather independent course of disease.19, 20

EIM may significantly increase the burden19, 21 of disease and EIM also have been associated with an increased need for corticosteroids, immunosuppressives, biologics as well as risk of colectomy.4, 22 In a Japanese study, preoperative EIM have also been shown to be an independent risk factor for postoperative complications and chronic pouchitis.23

Considering the relation of EIM and course of IBD, one might assume that the activity of those EIM, that are known to frequently run parallel to the underlying IBD would considerably improve or even entirely cease in patients having undergone total colectomy. In contrast, no such beneficial effect subsequent to colectomy would be expected in EIM that run independently from the course of IBD. Interestingly, literature on EIM and colectomy in IBD currently remains scarce, with so far only a single prior study in UC patients to the best of our knowledge.24 In this retrospective study from the US, PSC and ocular manifestations remained unchanged in patients with total colectomy with pouch, ileostomy or ileorectostomy, whereas all other EIM showed a variable, although rather favourable disease course subsequent to colectomy.

Therefore, the aim of our study was to evaluate the course of EIM in patients with CD and UC undergoing colectomy using the prospectively collected data from the Swiss IBD Cohort.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Swiss IBD-Patients

The Swiss IBD Cohort study (SIBDCS) was approved by local authorities and ethics committees and launched in 2006; cumulatively collecting data of approximately 4000 IBD patients in Switzerland. Several institutions including university hospitals, regional hospitals and private practices located all over Switzerland are responsible for the recruitment of patients with the University of Lausanne as the coordinating- and database-centre. Retrospective data have been obtained from patient charts since diagnosis regarding medical history of IBD prior to inclusion into the SIBDCS (retrospective collection) and thereafter a prospective collection of comprehensive clinical data during medical visits at inclusion and annual follow-up by gastroenterologist and study coordinators using standardized reporting forms. In addition, patients are directly interrogated at inclusion and annual follow-up independent from any health care professional (i.e., pure patient-reported outcome measurement) by specific and also standardized patient questionnaires. All forms are then transmitted to Lausanne for validation and entry into the database.25, 26

Amongst others, the SIBDCS collects specific information about IBD, disease activity, quality of life and EIMs. Approval from the local ethic committees for the SIBDCS was provided in 2005 (KEK-ZH 1316) and renewed in 2018 (2018-02068). All participants provide an informed consent form at the time of inclusion into the SIBDCS.

For this study, only patients with at least one visit before and one visit after partial or total colectomy during the prospective follow-up in the SIBDCS from 2006 until October 2020 were included into the analysis. Accordingly, data on EIM and medication before colectomy was available for the analysed patients. Therefore, patients with colectomy before inclusion into the SIBDCS were excluded due to lack of robust and prospectively obtained data before colectomy. Furthermore, we decided to exclude patients with unspecified IBD (IBDu) due to small sample size, allowing pure subgroup analysis for CU and CD. In contrast, no subgroup analysis could be performed with regards to the primary indication for colectomy, that is, disease refractory to medical therapy versus dysplasia/malignancy. As outlined in detail in a previous analysis of SIBDCS by our group,4 refractory disease by far represents the most frequent indication in the vast majority of patients undergoing colectomy (only 4.8% and 7.1%, respectively due to colorectal cancer and dysplasia).

Statistics

Data was analysed using Stata (StataCorp, College Station, TX 77845 Version 16.0) with descriptive statistics, bivariate and multivariate analysis. Quantitative variables were summarized as mean, standard deviation and range if they were normally distributed. Non-normally distributed variables were summarized as median, interquartile range (IQR) and range. Chi-Square test was used to test differences between groups of categorical variables. Congruent with standard statistical procedures Fisher exact test was used for small sample size comparisons, that is, less than 5 subjects per group. Furthermore, propensity score matching was performed to investigate the individual effect of different parameters. Propensity score matching was computed with EIM only after colectomy and EIM only before colectomy as dependent variables as well as age at colectomy, disease duration, gender and refractory disease as explanatory variables. Due to the sample size, it was not possible to include more explanatory variables into the propensity score analysis.

RESULTS

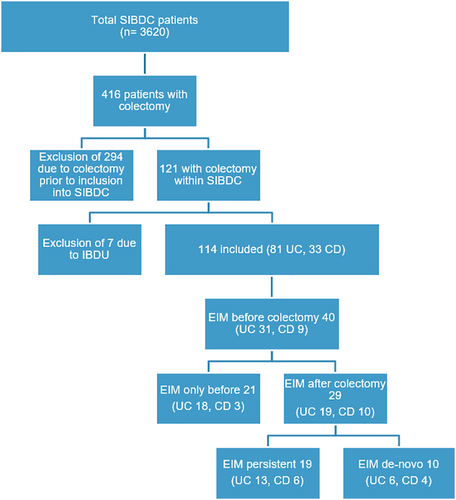

Amongst a total of 3620 IBD patients in the SIBCS (1549 UC, 1941 CD and 130 IBDU) 416 patients underwent colectomy. Out of these, 294 (70.7%) had a colectomy prior to inclusion into the SIBDCS and in 121 (29.3%) patients, colectomy was performed during the prospective follow-up period within the SIBDCS. Of the 121 patients undergoing colectomy during SIBDCS’s prospective follow-up, 81 (67.3%) were diagnosed with UC, 33 (27%) with CD and 7 (5.7%) with IBD unclassified. Only patients who underwent colectomy during the prospective SIBDCS follow-up and who were diagnosed with either UC or CD (i.e., not IBDu) were considered for further analyses in our study (Figure 1).

Flowchart. This figure displays a flow chart of patient selection in absolute numbers in this study

The average patient undergoing colectomy in the SIBDCS was 40 years of age and had the disease diagnosed 10 years ago (Table 1). The median length of follow-up in the cohort was 5.11 years (IQR 6.5, range 0–13 years). Significantly more patients with CD were smokers. Furthermore, CD patients had a significantly higher rate of current or past therapy with anti-tumornecrosis factor or immunomodulatory medication compared to UC. Looking at medical therapies received after colectomy, we did not observe any significant differences between patients with versus without EIM. The surgical types of colectomy are displayed in Table 2.

| Patient characteristics | Patients with EIM after colectomy | Patients without EIM after colectomy | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Numbers n | 29 | 85 | |

| Female n (%) | 14 (48.3%) | 32 (37.7%) | 0.314 |

| Mean (SD) age at colectomy [years]: | 41 (9), range (22– 65) | 40 (15.5), range (8 – 81) | 0.316 |

| Median (IQR) disease duration at colectomy [years] | 11 (8.2), range (2 - 32) | 8.4 (10), range (1.5- 36) | 0.165 |

| Type of IBD n (%) | |||

| Ulcerative colitis | 19 (65.5%) | 60 (70.6%) | 0.609 |

| Crohn’s disease | 10 (34.5%) | 25 (29.4%) | |

| Smoking status at colectomy n (%) | |||

| Yes | 4 (13.8%) | 8 (9.4%) | 0.507 |

| No | 25 (86.2%) | 77 (90.6%) | |

| Current therapy at colectomy n (%) | |||

| 5-ASA | 5 (17.2%) | 22 (25.9%) | 0.45 |

| Steroid | 3 (10.3%) | 17 (20%) | 0.238 |

| Immunomodulators | 4 (13.8%) | 14 (16.5%) | 0.733 |

| Anti TNF | 10 (34.5%) | 14 (16.5%) | 0.04 |

| Vedolizumab | 1 (3.5%) | 1 (1.2%) | 0.421 |

| Past therapy n (%) | |||

| 5-ASA | 22 (75.9%) | 64 (75.3%) | 0.951 |

| Steroid | 27 (93.1%) | 81 (95.3%) | 0.648 |

| Immunomodulators | 23 (79.3%) | 68 (80%) | 0.936 |

| Anti-TNF | 19 (65.5%) | 59 (69.4%) | 0.697 |

| Vedolizumab | 3 (10.3%) | 10 (11.8%) | 0.835 |

| Therapy after colectomya n (%) | |||

| 5-ASA | 2 (7%) | 5 (5.9%) | 0.844 |

| Steroid | 3 (10.3%) | 6 (7.1%) | 0.571 |

| Immunomodulators | 3 (10.3%) | 6 (7.1%) | 0.571 |

| Anti TNF | 1 (3.5%) | 6 (7.1%) | 0.484 |

| Vedolizumab | 1 (10.3%) | 1 (11.8%) | 0.421 |

- Abbreviations: 5-ASA, aminosalicylic acid; anti-TNF, anti-tumornecrosis factor; CD, Crohn’s disease; EIM, extraintestinal manifestation; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation; SIBDCS, Swiss IBD Cohort study; UC, ulcerative colitis.

- a Cumulative treatments during SIBDCS follow-up up to 5 years after colectomy; statistical tests used: Chi2 and Kruskal Wallis.

| Type of colectomy | Ulcerative colitis n (%) | Crohn’s disease n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Total proctocolectomy | 64 (79.0) | 1 (3.0) |

| Subtotal colectomy | 16 (19.8) | 7 (21.2) |

| Right colectomy | 3 (3.7) | 15 (45.5) |

| Left colectomy | 5 (6.2) | 12 (36.4) |

- Abbreviations: CD, Crohn’s disease; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; UC, ulcerative colitis.

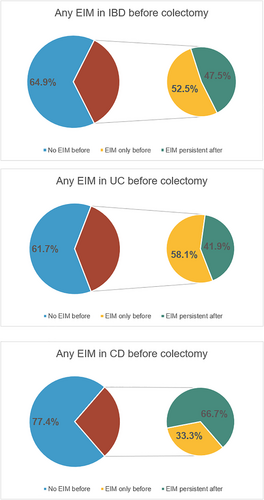

No EIM had been present before colectomy in 74 (64.9%) out of the 114 patients. Amongst these 74 patients, 10 (UC n = 6, 7.4%, CD n = 4, 12.1%) developed de-novo EIM after colectomy, that is 13.5%. The remaining 40 patients (35.1% of total, UC n = 31, 38.3% of total, CD n = 9, 27.3% of total) undergoing colectomy had experienced at least one EIM before colectomy. Significantly more patients with UC compared to CD patients experienced a cessation of previously existing EIM after colectomy (52.5% cessation in IBD overall, UC n = 18, 58.1% cessation, CD n = 3, 33.3% cessation, p < 0.001, Figure 2). However, EIM persisted overall in almost every second patient (47.5%).

Frequency of extraintestinal manifestation (EIM) before and after colectomy. Pie charts depicting percentage of patients with EIM before and after colectomy in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) overall (upper row), ulcerative colitis (UC; middle row) and Crohn’s disease (CD; lower row)

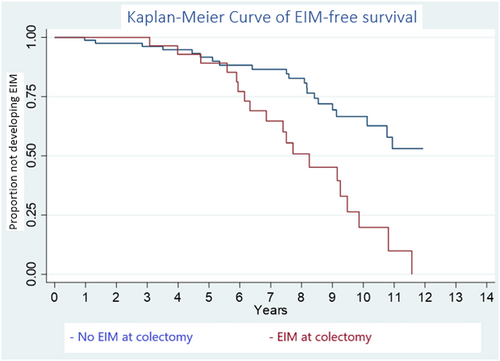

After colectomy, any EIM was present in 29 out of 114 patients (25.4%). Nineteen out of these 29 patients (65.5%) presented with persisting EIM despite colectomy. In contrast, in the other 10 EIM with EIM subsequent to colectomy, a de-novo appearance of EIM after colectomy was observed. Using a Kaplan–Meier curve, we observed that patients with EIM at the time of colectomy still harbour a 50% chance of persistent or recurrent EIM even 8 years thereafter. Importantly, freedom from EIM at colectomy was associated with sustained freedom from any EIM 8 years after colectomy in almost 75% of patients (Figure 3).

Depicting a Kaplan–Meier curve. Reading example: The probability of developing new extraintestinal manifestation (EIM) 10 years after colectomy when having EIM at colectomy is approximately 0.25 and the probability of not developing new EIM when not having EIM at colectomy is approximately 0.57 at 10 years

Looking separately at UC and CD patients, prior to colectomy 31 out of 81 patients in UC (38.3%) and 9 out of 33 in CD (27.3%) suffered from EIM. After colectomy however, only 13 UC and 6 CD revealed any EIM, corresponding to a significant reduction of 58.1% and 33.3% after colectomy in UC and CD (p = 0.002 and p = 0.005).

With regards to specific EIM, peripheral arthritis/arthralgia by far represented the most frequently reported EIM, accounting for 75.6% of all reported EIM, followed by aphthous oral ulcers (22.0%; Table 3).

| EIMs | EIM before colectomy n (%) | EIM still after colectomy n (%) | EIM new after colectomy n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total EIM | 40 (35.1) | 19 (16.7) | 10 (8.8) |

| Peripheral arthritis | 30 (26.3) | 13 (11.4) | 8 (7.0) |

| Uveitis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.8) |

| Erythema nodosum | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Aphthous oral ulcers | 8 (7.0) | 2 (1.8) | 1 (0.9) |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | 5 (4.4) | 2 (1.8) | 1 (0.9) |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis | 4 (3.5) | 4 (3.5) | 2 (1.8) |

| Primary sacroiliitis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.9) |

By means of propensity score matching we did not identify factors that could predict occurrence of de-novo EIM or cessation of EIM. Specifically, neither age at colectomy, gender nor disease duration at colectomy were associated with occurrence or cessation of EIM after colectomy (see Tables S4 & S5).

DISCUSSION

Having analysed the course of EIM in IBD patients undergoing colectomy we could obtain several important findings. First, EIM that were present before surgical intervention will persist in about half of patients after surgery in IBD. Second, the effect of surgery appears to be more favourable in UC than in CD, with only 41.9% in UC persistently suffering from EIM after colectomy compared to 67% in CD. Third, absence of EIM prior to surgery unfortunately does not imply continuous freedom from EIM after surgery. Indeed, up to one in seven IBD patients developed de-novo EIM after colectomy (again, there was a numerically but not statistically significant difference in favour for UC vs. CD with 16% vs. 21% de-novo EIM, respectively).

In contrast to recent large-scale registry data (Algaba, Guerra et al. based on the ENEIDA registry21) from Spain, where several risk factors for EIM have been described, we did not identify gender, disease duration at colectomy or age at colectomy as risk factors associated with cessation or de-novo development of EIM after colectomy. This difference might be due to the lower patient number in our study. Of note, the most frequently reported EIM was peripheral arthritis/arthralgia, independent of CD or UC. To this date it remains unclear, whether distinctive EIM, such as for example peripheral arthritis Type 1 (pain in <6 joints, mostly large, weight-bearing joints) with classically a course of activity in parallel with course of underlying IBD have a different course of activity after colectomy than those EIM with a well-recognized independent course of activity from underlying IBD.14, 18-20 Interestingly, according to our data, rates of peripheral arthritis appear to substantially decline after proctocolectomy. These data support the results obtained by Goudet et al.24 where a complete resolution of arthritis in almost 41%–59% of patients after surgical intervention in UC patients was found. Considering EIM with a known independent course of activity from underlying IBD14, 19, 20 PSC might be the most prominent example. In our study, in all patients with established PSC prior colectomy, PSC persisted thereafter—without any exception. Of note, none of the CD patients in our study was diagnosed with PSC. These findings are also in line with the study from Goudet et al.24 where aggravation or persistent PSC was reported in 86% of UC patients following colectomy.

Our study indicates, that in the process of evaluating an indication for colectomy and carefully balancing the pros and cons in meticulous discussions between patient and physicians, EIM should also represent one piece of the puzzle in the complex decision-making process. Importantly, the potential effect of colectomy on the course of activity of any given EIM present prior to colectomy may be extremely variable and heterogenous. Depending on the specific type of EIM, rates of EIM disappearance after colectomy may be as high as 72% (peripheral arthritis in UC) or as low as 0% (PSC in UC). Hence presence of any EIM and the potential subsequent course of EIM after colectomy should be discussed with the patient to set realistic expectations for the future course of disease after surgery. Unfortunately, and as mentioned previously, the literature basis for such a discussion yet is extremely scarce and further studies including more patients with a vigorous follow-up focussing on a dedicated assessment of EIM in line with our current work will be important.

Interestingly, our data indicate that despite beneficial effects of colectomy regarding EIM in both, CD and UC, the net benefit of colectomy appears to be stronger in UC as opposed to CD. Our study did not identify risk factors for cessation or development of de-novo EIM before or after colectomy. Age at colectomy as well as disease duration at colectomy or gender did not influence the course of EIM. We speculate that this discrepancy might be due to the fact, that CD represents a disease state with a more systemic connotation, and therefore the act of a purely mechanical removal of the inflamed colon may be associated with less beneficial disease-modifying effects.

Our study has several strengths and limitations. A strength of our study is the highly relevant topic, enlightening hitherto ill-defined features of EIM after surgical interventions which up to now have only been investigated in a single study.24 Moreover, this study was limited to UC patients, whereas our analysis also considered CD patients. Limitations include the small sample size since despite the rather high number of available IBD patients within the SIBDCS (around 4000 patients), colectomy represents a rather rare event. Due to improvements in medical treatment, colectomy rates might continue to decline in the future, further complicating the gathering of data of larger number of patients and multi-centre efforts will be required. Another important limitation refers to the limited standardization and lack of validated outcome measures on how course of EIM in IBD patients are recorded. This limitation refers to prospective and retrospective investigations on EIM in IBD in general and indeed also to our study in specific. Another limitation concerns postoperative disease activity. Unfortunately, there are no validated scores to assess disease activity after total proctocolectomy, making it difficult to compare pre-and postoperative disease activity. Something similar applies to pouchitis, presumably the most frequent and relevant complication of total colectomy. In our investigation, data on pouchitis are not recorded in a standardized fashion in the SIBDCS. However, the vast majority of patients suffers from only one or a small number of distinctive episodes of pouchitis, These patients only undergo endoscopic and histologic evaluation in a minority of cases, which would be a prerequisite to determine the pouchitis disease activity index.27 Short-term antibiotic treatment is frequently associated with a prolonged freedom from further episodes of pouchitis, yet patients in Switzerland rather receive a course of short-term antibiotics from their general practitioners (GP) than from their gastroenterologist. The primary care of GPs and prescription of antibiotics by the GP might be unique in the Swiss healthcare system, whereas in other countries those patients might rather be seen directly by a gastroenterologist. However, since pouchitis resolves in about 95% of cases, we do not consider that to be a major concern.28 Finally, our study has a non-interventional study design but due to the specific study question, neither a double-blind nor randomized controlled study design will be feasible.

In conclusion our data indicate that complete cessation of EIM after colectomy occurs in about every second patient overall and may be less common in CD than in UC patients. Furthermore, rates of complete cessation after colectomy are highly variable according to the type of EIM with best prospects for peripheral arthritis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by research grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation to Gerhard Rogler (Grant No. 310030-120312), and the Swiss IBD Cohort (BASEC-Number 2018-02068).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

René Roth: Conception and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting and revising; Stephan Vavricka: Drafting and revising, Michael Schar: Analysis and interpretation of data, drafting and revising; Philipp Schreiner: Drafting and revising; Ekaterina Safroneeva: Drafting and revising; Thomas Greuter: Analysis and interpretation of data, drafting and revising; Jonas Zeitz: Drafting and revising; Benjamin Misselwitz: Analysis and interpretation of data, drafting and revising; Alain Schoepfer: Drafting and revising; Mamadou Pathé Barry: Analysis and interpretation of data; Gerhard Rogler: Conception and design of the study, drafting and revising; Luc Biedermann: Conception and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting and revising.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly due to privacy reasons of individuals that participated in the study. This manuscript, including related data, figures and tables has not been previously published. This manuscript is not under consideration in another medical journal.