Outcomes and Benefits of a Managerial Global Mind-set: An Exploratory Study with Senior Executives in North America and India

Abstract

Globalization and its associated challenges are compelling managers in multinational corporations to develop appropriate skill sets. An emerging body of research in international management has suggested that meeting this challenge requires the cultivation and development of a managerial global mind-set. There has been limited empirical work on the outcomes and benefits of a managerial global mind-set and consequently this article attempts to fill that gap. Based on semistructured interviews with a total of 56 senior executives of multinational corporations in North America (United States and Canada) and India, this study identifies five outcomes of a global mind-set with benefits for managers and their organizations. The findings have theoretical implications, which are discussed along with their practical applications for multinational corporations, their senior executives, and human resource professionals, with respect to identifying management development programs that assist in the cultivation and nurturing of a global mind-set. © 2014 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Introduction

Globalization is complex, and multinational corporations around the globe are experiencing its profound effects (Levy, Taylor, Boyacigiller, & Beechler, 2007a; Parkan, 2009; Rogers & Blonski, 2010). Most would agree that globalization has been driven by a confluence of factors, including (inter alia) markets, costs, competition, governmental imperatives (Kedia & Mukherji, 1999; Yip, Johannson, & Roos, 1997), and new information and communication technologies (Sealy, Wehrmeyer, France, & Leach, 2010). These drivers of globalization pose complex challenges to multinational corporations. Todd and Javalgi (2007, pp. 171–174) suggested that multinationals face three such challenges, namely, “country-specific, industry-specific, and firm-specific.” The country- and industry-level challenges encompass the levels of government support or obstruction, infrastructural issues, technological capabilities, and demographic characteristics (both labour and consumer markets). Labor market shortfalls may include (inter alia) lack of language skills, low quality of educational systems, or lack of cultural fit among both local and foreign employees and managers in some developing countries. At the firm level, multiple levels of competition faced by global companies, namely, global business acumen, global citizenship, and organization-level global mind-set defined as “the capacity to engage in a boundary-less and synthesized cognitive process that identifies opportunities and innovation in complexity” (Rogers & Blonski, 2010, p. 19) present the most significant challenges for multinationals. However, of all the challenges faced by global organizations, one of the most crucial is the importance of the capacities of global managers. That is, whether organizations possess the right managers with the appropriate skill sets, competencies, attributes and values, especially those with the greatest potential for the development of multinational corporations towards sustained competitive advantage (Gupta & Govindarajan, 2002).

As Cabrera and Bowen (2005, p. 799) explained, the art of managing global organizations requires the capability of “expanding scale, network or knowledge economies beyond local markets, (to devise) business models that exploit economic inefficiencies across national lines.” Johnson (2011, p. 30) explained that global managers need certain attributes—“change agents, ethical, decisive, confident, proactive, critical thinkers, versatile, process-focused, open-minded, and accountability.” Other researchers (Bartlett & Ghoshal, 1989, 1998; Baruch, 2002; Black & Gregersen, 1999; Cabrera & Bowen, 2005; Hofstede, 1980; Stanek, 2000) have identified various complementary descriptors, including particular demographic characteristics (age, gender, marital status); individual features (nationality, personality dimensions); and/or behavioural elements (desire to communicate, “broad-based sociability” [Stanek, 2000, p. 232]); cultural flexibility, collaborative negotiating styles, “cosmopolitan” orientation, open-mindedness and inquisitiveness (Kedia & Mukherji, 1999, p. 232). Baruch (2002) questioned the overall concept of a global manager but then explicated similar attributes to those described earlier. Kedia and Mukherji (1999) and Cohen (2010) asserted that global managers need an “altered mind-set,” suggesting that they need “to have openness that allows a global mind-set to form, evolve and develop” (p. 232). Cohen (2010, pp. 6–7) elaborated further on this by suggesting that global managers need to possess a global mind-set that arguably helps balance three associated business dichotomies, namely global formalization versus local flexibility, global standards versus local customization, and global dictates versus local delegation. And it is this contentious notion of a global mind-set that has intrigued international management researchers for much of the past two decades. Based on a review of the literature on the theory of global mind-set development, this study used an exploratory, qualitative methodology in an attempt to identify the outcomes and benefits of a managerial global mind-set. The next section reviews the relevant literature, identifies the potential research gap, and delineates the aims of the study. The subsequent sections provide details of the qualitative methodology, and findings from the exploratory empirical study of a sample of 56 senior executives employed in North American and Indian multinational corporations (MNCs).

Literature Review

Global Mind-set

Globalization is a major force driving the reconfiguration of organizations that is challenging managers at all levels. Over the past two decades, a number of researchers have suggested that meeting this challenge requires the development of a managerial global mind-set (Arora, Jaju, Kefalas, & Perenich, 2004; Bartlett & Ghoshal, 1989; Bowen & Inkpen, 2009; Cohen, 2010; Govindarajan & Gupta, 2001; Gupta & Govindarajan, 2002; Javidan & Teagarden, 2011; Javidan, Teagarden, & Bowen, 2010; Javidan et al., 2011; Kefalas, 1998; Levy, Beechler, Taylor, & Boyacigiller, 2007b; Lovvorn & Chen, 2011; Murtha, Lenway, & Bagozzi, 1998; Rhinesmith, 1992, 1993, 1995; Rogers & Blonski, 2010; Taylor, Levy, Boyacigiller, & Beechler, 2008; Teagarden, 2009). This growing body of international management literature has emphasised the importance of the cultivation and development of a global mind-set as one of the critical elements in sustaining an intelligent global organization with implications for organizations and their management. Managers with a global mind-set have a broader global outlook and a “global business orientation and are adaptable to the local environment and culture” (Story & Barbuto, 2011, p. 380). Kedia and Mukherji (1999) and Kefalas (1998) posited that senior managers with a stronger global mind-set focus on the global market and have a better understanding of the dynamics of operating in diverse marketplaces. In this regard, global mind-sets have been linked to expatriate success wherein managers with a stronger global mind-set posted on overseas assignments have reported better overall performance (Javidan et al., 2011). Another benefit of a stronger managerial global mind-set was elucidated by Levy et al. (2007b), who contended that a stronger managerial global mind-set is linked to strategic decision making where managers in decision-making responsibilities on strategy-related matters have a better grasp of the relevant information to take the right decision. These decisions can vary from strategic intent where organizations want to expand overseas to strategy formulation and implementation.

Story and Barbuto (2011, p. 377), however, observed that “many frameworks of global mind-set have been proposed in the literature but no clear consensus has been observed.” Table 1 presents the different conceptualizations of a global mind-set. While many scholars agree that a global mind-set is essentially a cognitive structure (for example, Levy et al., 2007b; Lovvorn & Chen, 2011; Rogers & Blonski, 2010), and that human beings are highly dependent on cognitive filters to sort otherwise overwhelming complexity in the information environment, there is still considerable argument about the essential components of a global mind-set and how it is cultivated and nurtured (Bouquet, 2005; Gupta & Govindarajan, 2002; Jeannet, 2000; Levy et al., 2007b; Lovvorn & Chen, 2011; Murtha et al., 1998; Perlmutter, 1969; Rhinesmith, 1992, 1993, 1995; Rogers & Blonski, 2010). It can be seen from Table 1 that many authors have attempted to define global mind-sets and their antecedents and consequences, with varying degrees of effectiveness and from different perspectives. Definitions embrace both organizational and managerial perspectives: “organizations and their employees observe and make sense of their surroundings by processing information through their own unique cognitive filters” (Gupta & Govindarajan, 2002, p. 175). Illustrating the organizational perspective, Kefalas (1998, p. 549), for example, suggested that the existence of a corporate global mind-set can be measured through such indicators as the presence of foreigners on the board of directors, or in top management positions; requirements for previous international experience for potential managers; a lack of distinctions between headquarters and international subsidiaries; multicultural team-building workshops; and evidence of the implementation of new ideas or products suggested by foreign affiliates.

| Source | Conceptualization of a Global Mind-set |

|---|---|

| Fayerweather (1969); Prahalad & Doz (1987); Bartlett & Ghoshal (1998) | A transnational mentality is the capacity to deliver global integration, national responsiveness, and worldwide learning simultaneously (“a matrix in the minds of managers”). |

| Perlmutter (1969); Heenan & Perlmutter (1979) | Geocentrism is a global systems approach to decision making or state of mind where “… HQ and subsidiaries see themselves as part of an organic worldwide entity … good ideas come from any country and go to any country within the firm” (1979: 21) |

| Rhinesmith (1993); Jeanett (2000) | Global mind-set is a state of mind able to understand a business, an industry, or a particular market on a global basis. |

|

Calof & Beamish (1994) |

Centricity is defined as a person's attitude towards foreign cultures. Geocentrism can be characterized by the following factors: “… all major decisions are made centrally … substantial co-ordination exists between offices …, and focus is on global systems.” |

|

Calori, Johnson, & Sarnin (1994) |

Global mind-set is viewed as a cognitive structure or mental map that allows a CEO to comprehend the complexity of a firm's worldwide environment. |

|

Kobrin (1994) |

Geocentrism defined using Heenan and Perlmutter (1979) above. |

|

Sambharya (1996) |

Study taps into the “cognitive state” or “belief and values” of a top team. |

|

Kefalas (1998) |

Global mind-set is defined as “a predisposition to see the world in a particular way that sets boundaries and provides explanations for why things are the way they are, while at the same time establishing guidance for ways in which we should behave.” |

| Murtha et al. (1998) | Global mind-set defined using Fayerweather (1969) and Prahalad and Doz (1987). |

| Beechler, Taylor, Boyacigiller, & Levy (1999); Arora et al. (2004); Taylor et al. (2008); Lovvorn & Chen (2010) | Global mind-set is linked to cultural and emotional intelligence with a focus on cultural diversity appreciation. |

|

Govindarajan & Gupta (2001) |

Global mind-set is defined as a “… knowledge structure … that combines an openness to an awareness of diversity across cultures and markets with a propensity and ability to synthesize across this diversity.” |

| Nummela, Saarenketo & Puumalainen, (2004) | Global mind-set is defined as “a manager's positive attitude towards international affairs and also to his or her ability to adjust to different customs and cultures.” |

|

Bouquet (2005) |

A behavioral approach to measure global mind-set focusing on the actual (and more readily observable) time and effort that top team members devote to making sense of international issues, both for themselves and for the benefit of the multinational enterprise (MNE) overall. |

|

Levy et al. (2007b) |

Global mind-set includes a cultural and a strategic domain. |

|

Maak & Pless (2009) |

Added a perspective of “cosmopolitanism,” which translated in specific global leadership qualities. |

| Ananthram, Chatterjee, & Pearson (2010) | Global mind-set is defined as, “the ability and willingness of managers to think, act, and transcend boundaries of goals, values and competencies on a global scale.” |

|

Rogers & Blonski (2010) |

Global mind-set is defined as, “the capacity to engage in a boundaryless and synthesized cognitive process that identifies opportunity and innovation in complexity.” |

|

Javidan et al. (2011) |

Global mind-set consists of three main dimensions: intellectual, psychological and social capital. |

Most researchers, however, have focused on the mind-sets of global managers rather than their organizations, believing that “a core managerial group with a global mentality is an essential component of a corporate global mind-set” (Begley & Boyd, 2003, p. 26). There is burgeoning evidence that reinforces the importance of managerial global mind-sets to the successful performance of contemporary organizations (Cohen, 2010; Gupta & Govindarajan, 2002; Lovvorn & Chen, 2011; Rogers & Blonski, 2010). This is because global mind-sets refer to cognitive, existential, and behavioral factors that will together create highly complex structures that are characterized by an openness to, and an articulation of, multiple cultural and strategic realities at both global and local levels, and the ability to mediate and integrate across this multiplicity of factors (Levy et al., 2007b).

A careful review of the literature suggests that the definitions of managerial global mind-sets encompass personal philosophies or qualities, knowledge and skills, behaviors, or a combination of these. An early researcher (Perlmutter, 1969) introduced the notion of geocentrism (as opposed to ethnocentrism) built upon a cultural perspective. This theme was further developed by Heenan and Perlmutter (1979), Calof and Beamish (1994), and Kobrin (1994). Maak and Pless (2009, p. 546) added the perspective of “cosmopolitanism,” comprising four components—namely, political cosmopolitanism, ethical cosmopolitanism, cosmopolitan worldview, and cosmopolitan practice. These translate into particular leadership philosophies and practices, including active stakeholder engagement and dialogue, inclusiveness and subsidiarity, sustainability and stewardship, recognition of equal worth and dignity, and personal accountability. A more recent attempt to define global mind-sets was provided by Rogers and Blonski (2010, p. 19) who explained that global mind-sets allow executives to utilise their superior cognitive abilities and identify opportunities to innovate in complex environments without boundaries.

Several authors (Begley & Boyd, 2003; Javidan & Walker, 2012; Kefalas, 1998; Rhinesmith, 1992, 1995) subscribe to the view that the personal philosophies of senior managers contribute significantly to global mind-sets. Kefalas (1998) for example, concluded that global mind-sets encompass a set of boundaries and establish guidelines for ways in which managers need to behave. Similarly, Nummela, Saarenketo, and Puumalainen (2004, p. 53) described global mind-sets as “a manager's positive attitude towards international affairs” and also alluded to the manager's ability to adjust to different customs, cultures, and settings. Personal qualities include macro-perspectives, risk-taking, reliance on organizational processes rather than structures, openness and inclusivity, and valuing diversity (Rhinesmith, 1992, p. 63). Some more recent authors (e.g., Lovvorn & Chen, 2011; Rogers & Blonski, 2010) have linked global mind-sets to “cultural intelligence” and “emotional and social intelligence applied to a cultural context”—suggesting that a manager's ability to adapt globally depends heavily on their tolerance for ambiguity, broad personal skills sets, and the “capability of examining cultural cues from their international interactions” (Lovvorn & Chen, 2011, p. 279). Moreover, Arora et al. (2004) and Taylor et al. (2008) also link global mind-set to the appreciation of cultural diversity. In addition, Beechler and Javidan (2007) describe global mind-set as encompassing knowledge, cognitive ability, and psychological attributes that foster leadership in diverse cultural involvements. Levy et al. (2007b) concluded that a global mind-set facilitates cultural adaptability, which is vital in global business with diverse environments.

There is also some debate among researchers on the personal qualities that permeate global mind-sets. These include flexibility, sensitivity, analytical, and reflective capacities (Rhinesmith, 1992, pp. 3–4); curiosity, acceptance of complexity, diversity consciousness, a focus on continuous improvement, systems thinking, and a faith in organizational processes (Srinivas, 1995, pp. 30–31); or “mindfulness”, encompassing “a heightened awareness of and enhanced attention to current experiences or present reality” (Thomas, 2006, p. 84). Ananthram, Pearson, and Chatterjee (2010), Cabrera and Bowen (2005), Javidan et al. (2011), Kedia and Mukherji (1999), and Thomas (2006) all linked these personal qualities of global managers with specific knowledge, skills, behaviors, and managerial activities, suggesting that while global mind-sets may be derived partly from nature, they can also be nurtured through well-designed management development programs (Bhatnagar, 2006; Gaba, 2008). Identified knowledge and skills include international sociopolitical and economic perspectives (Kedia & Mukherji, 1999); the capacity to think globally and locally simultaneously (Begley and Boyd, 2003); environmental scanning, negotiation and persuasion, and uncertainty management competencies (Rhinesmith, 1992); and cultural agreeableness, motivation, and receptiveness (Baruch, 2002).

Ananthram and colleagues’ (2010) definition of a global mind-set encompasses the notions of personal qualities, knowledge, skills, and behaviors within a transformative organizational perspective, and includes two critical elements, namely, a deep appreciation of cultural and contextual diversity, and the ability to “integrate the imperatives of local and global paradoxes specific to an industry” (p. 147). This definition is used as a framework for this article, and its elements reflect Levy et al.’s (2007b) “cultural” and “strategic” perspectives, which together result in a “multi-dimensional perspective” (p. 232), and also emphasize the practical applications of managers’ personal qualities to the international operations of their industries and companies. Such a multidimensional perspective of a global mind-set is also supported by a seminal study by Javidan et al. (2011), who concluded that global mind-set consists of three major dimensions: global intellectual capital, global psychological capital, and global social capital.

As noted by Story and Barbuto (2010, pp. 377–378), however, “most of the research on global mind-set has examined the antecedents of global mind-set, but the importance of global mind-set has not been empirically derived.” It might be suggested that global mind-set research overall lacks strong empirical support, and in this article we address the particular research gap associated with its outcomes and benefits through an empirical study of North American and Indian senior executives employed in multinational corporations. The rationale for the choice of the two apparently disparate samples was to compare and contrast the perceptions of global mind-sets from two economically divergent contexts, namely, a developed context in North America and a developing context in India.

- What are the outcomes of a managerial global mind-set, as perceived by North American and Indian senior executives?

- What are the benefits of possessing a managerial global mind-set for global executives and multinational corporations?

Methodology

The data reported in this article were derived from a qualitative research study undertaken in North America (United States and Canada) and India. The data were collected through a series of semistructured interviews with a total of 56 senior managers (30 from North America with two-thirds based in the United States and a third in Canada; and 26 from India). This strategy of testing the results in two different contexts adds to the generalizability of the study findings.

Table 2 presents a summary of the participants’ backgrounds. All participants were senior executives with direct involvement in global management responsibilities and were employed in a multinational corporation in the private sector. All firms were well-established multinationals in both contexts. The North American participants were employed in a wide variety of business sectors including airlines, banking and finance, consulting, consumer goods, healthcare, information and communications technology, mining and pharmaceuticals. The Indian sample included senior executives employed in airlines, automobiles, banking, chemicals, consulting, consumer goods, information and communications technology and shipping services sectors. Seven of the participants from the North American sample and four from the Indian sample were female.

| # | Code | Face-to-Face/Telephone | Position | Industry | Gender | City |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CA1 | Face-to-face | Senior Vice President | Mining | Male | Toronto |

| 2 | CA2 | Face-to-face | Vice President | Mining | Male | Toronto |

| 3 | CA3 | Face-to-face | Senior Manager | Consumer products | Male | Toronto |

| 4 | CA4 | Face-to-face | Executive Manager | Consumer products | Male | Toronto |

| 5 | CA5 | Face-to-face | Divisional Head/Director | Mining | Female | Toronto |

| 6 | CA6 | Telephone | Vice President | Information technology | Male | Vancouver |

| 7 | CA7 | Face-to-face | Divisional Head | Banking and finance | Female | Toronto |

| 8 | CA8 | Face-to-face | Senior Manager | Consulting | Female | Toronto |

| 9 | CA9 | Face-to-face | Senior Manager | Airlines | Male | Toronto |

| 10 | CA10 | Face-to-face | Senior Manager | Consumer products | Male | Toronto |

| 11 | US1 | Face-to-face | Senior Manager | Consulting | Male | Boston |

| 12 | US2 | Telephone | Divisional Head | Consumer products | Male | Atlanta |

| 13 | US3 | Face-to-face | Senior Partner | Consulting | Male | Boston |

| 14 | US4 | Face-to-face | Senior Manager | Consulting | Male | Boston |

| 15 | US5 | Face-to-face | Vice President | Financial services | Male | Boston |

| 16 | US6 | Face-to-face | Senior Manager | Healthcare | Female | Boston |

| 17 | US7 | Face-to-face | Vice President | Healthcare | Male | Boston |

| 18 | US8 | Face-to-face | Vice President | Healthcare | Male | Boston |

| 19 | US9 | Telephone | Senior Manager | Information technology and communications | Male | New York |

| 20 | US10 | Face-to-face | Senior Manager | Information technology and communications | Female | New York |

| 21 | US11 | Face-to-face | Senior Manager | Consumer goods | Male | Philadelphia |

| 22 | US12 | Telephone | Senior Manager | Accounting and financial services | Male | New York |

| 23 | US13 | Telephone | Director | Healthcare | Female | Boston |

| 24 | US14 | Face-to-face | Senior Manager | Information technology | Male | Seattle |

| 25 | US15 | Telephone | Vice President | Information technology and communications | Male | New York |

| 26 | US16 | Telephone | Senior Manager | Information technology | Male | New York |

| 27 | US17 | Telephone | Divisional Head | Information technology | Male | Seattle |

| 28 | US18 | Telephone | Senior Manager | Consulting | Female | San Francisco |

| 29 | US19 | Face-to-face | Senior Manager | Consumer products | Male | San Francisco |

| 30 | US20 | Face-to-face | Senior Manager | Information technology | Male | San Francisco |

| 31 | IN1 | Face-to-face | Vice President | Consumer products | Male | Mumbai |

| 32 | IN2 | Telephone | Chief Executive Officer | Information technology and communications | Male | Mumbai |

| 33 | IN3 | Telephone | Associate Director | Telecommunications | Male | Mumbai |

| 34 | IN4 | Telephone | Chief Executive Officer | Consulting | Female | Mumbai |

| 35 | IN5 | Telephone | Senior Manager | Chemical Industry | Male | Mumbai |

| 36 | IN6 | Face-to-face | Divisional Head | Automobile Industry | Male | Mumbai |

| 37 | IN7 | Face-to-face | Assistant Vice President | Banking | Male | Mumbai |

| 38 | IN8 | Face-to-face | Vice President | Banking | Male | Mumbai |

| 39 | IN9 | Face-to-face | Divisional Head | Airlines | Male | Mumbai |

| 40 | IN10 | Face-to-face | Chief Executive Officer | Information technology and communications | Male | Mumbai |

| 41 | IN11 | Face-to-face | Divisional Head | Information technology and communications | Male | Mumbai |

| 42 | IN12 | Face-to-face | Vice President | Banking | Male | Mumbai |

| 43 | IN13 | Telephone | Senior Manager | Consultancy | Male | Mumbai |

| 44 | IN14 | Face-to-face | Vice President | Banking | Male | Mumbai |

| 45 | IN15 | Face-to-face | Senior Manager | Consumer products | Female | Mumbai |

| 46 | IN16 | Face-to-face | Senior Manager | Banking | Male | Mumbai |

| 47 | IN17 | Face-to-face | Senior Manager | Shipping services | Male | Mumbai |

| 48 | IN18 | Face-to-face | Senior Manager | Telecommunications | Male | Mumbai |

| 49 | IN19 | Telephone | Vice President | Banking | Male | Mumbai |

| 50 | IN20 | Face-to-face | Divisional Head | Chemical Industry | Female | Mumbai |

| 51 | IN21 | Telephone | Senior Manager | Airlines | Male | Mumbai |

| 52 | IN22 | Telephone | Divisional Head | Consumer products | Male | Mumbai |

| 53 | IN23 | Telephone | Senior Partner | Consultancy | Male | Mumbai |

| 54 | IN24 | Telephone | General Manager | Consumer products | Male | Mumbai |

| 55 | IN25 | Telephone | Senior Manager | Banking | Female | Mumbai |

| 56 | IN26 | Telephone | Divisional Head | Telecommunications | Male | Mumbai |

- Note: CA1–CA10 represent interviews conducted in Canada; US1–US20 represent interviews conducted in the USA; IN1–IN26 represent interviews conducted in India.

Twenty-one of the interviews were face-to-face and the remaining nine were conducted by telephone in North America. Fourteen interviews in India were conducted face-to-face and the remaining were telephone interviews. All interviews used the same schedule of questions. The interviews were conducted by an experienced researcher with cross-cultural awareness using the criteria of a successful interviewer recommended by Kvale (1996). These criteria include being knowledgeable about the themes in the interview, structuring the interview to facilitate the process smoothly, maintaining proper interview etiquettes including being culturally sensitive, being open to new directions that are important to the interviewee and giving the interviewee opportunities to raise any concerns or issues. Furthermore, as suggested by Kvale (2007), the interview schedule and questions was pilot tested with two colleagues with significant international research experience who verified the questions and suggested minor changes to the questions in order to maintain vocabulary equivalence between the two contexts—North America and India. There did not appear to be any confusion about the questions among the interviewees in either context.

The interviews were conducted in an average time of 40 minutes. The interview questions were mailed to the participants beforehand so that they could prepare for the interview. The participants were asked to discuss the important skill-sets for global managers. When they directly or indirectly alluded to a “global mind-set” as being an important skill set, the interviewer probed them further into its components and outcomes. In addition, the participants were asked to explain how important it was for the managers in their respective organizations to possess a global mind-set and to highlight the benefits of a managerial global mind-set for global managers and multinational corporations. The participants were encouraged to use anecdotal evidence to justify their opinions. The structure of the interviews was deliberately kept loose (i.e., semistructured, open-ended format) in order to allow unexpected and emergent themes to emanate.

Sinkovics, Penz, and Ghauri (2008) advocate the use of formalized and software-based procedures for the analysis and interpretation of qualitative interview data. The current study is another example of how qualitative, open-ended interviewing, that was analyzed using formalized software, can lead to new conceptual insights and themes (Buckley & Chapman, 1997; Welch, Welch, & Tahvanainen, 2008). Each interview was transcribed verbatim and the interview transcripts were imported into NVivo, a widely used software package that enables a systematic process of qualitative content analysis. Lindsay (2004, p. 488) observed that NVivo can provide “more rigor and traceability” than manual coding and is useful for identifying emerging categories and themes. A variable-oriented strategy was used in order to find themes that cut across cases. As such, an initial set of codes was devised from the relevant literature on global mind-set and later refined (Miles & Huberman, 1994).

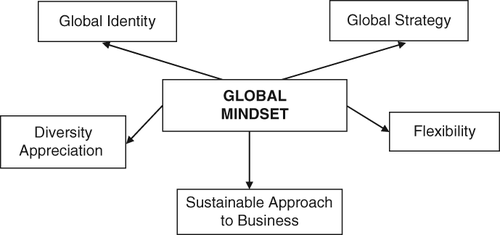

Two researchers independently coded the same piece of data from the transcripts and compared the codes by discussing the similarities and differences in their application of the codes in order to maximize interrater reliability (Frankfort-Nachmias & Nachmias, 1996; Keaveney, 1995). This technique of using multiple independent coders has been widely acknowledged as reducing coder bias as compared to using a single coder (Miles & Huberman, 1994). After ongoing discussions between the coders and three iterations, linkages between the codes were identified and grouped into five main components giving an interrater reliability of 85 per cent (Miles & Huberman, 1994). The five components included (1) global identity, (2) global strategy, (3) flexibility, (4) sustainable approach to business, and (5) diversity appreciation.

Results

Five outcomes of global mind-sets were derived from the qualitative analysis of the interviewees’ responses. They include global identity, global strategy, flexibility, sustainable approach to business, and diversity appreciation. Each is considered separately wherein anecdotal evidence from the senior managers provides underpinning for the importance of a global mind-set for themselves and the organizations that they represent. The implications of the findings are then discussed holistically in the Discussion section.

Global Identity

A global mind-set is very important, you know, as having a uni-dimensional, uni-cultural mind-set among managers tends to be very limiting. You need to be able to see beyond your own identity. (US11)

We operate in a globalized boundaryless world and managers need to understand that. So within that globalization context, it is really, you know having that global mind-set is really important. The mind-set is the driver. (US9)

And sometimes the manager who put his hand up and said—yeah let's move our team off to India—sometimes they would be out of a job, so sometimes that wouldn't be a good move for them at a personal level. But they were a team player and having this global mind-set gives them a psychological edge and this really helps the organization. (CA8)

So according to me a managerial global mind-set is very important for any organization or industry that has international customers but also those solutions or products that they offer will have a wider application globally. I don't think any organization and its managers can stay away from having a global mind-set. (IN3)

… the global mind-set is one that is being open to the opportunities that arise and it is also prepared to get the best out of it for the organization and also for themselves. (IN16)

In today's environment it is also very important for employees to be able to get their global perspective of the business rather than stay in a particular region or jurisdiction or country. We ensure that our senior managers possess this mind-set which enables them to bypass geographic and other boundaries. (IN14)

The comments made by the North American and Indian managers are supported by the literature. Managers of global organizations involved in cross-border business activities are perceived to possess a global identity giving them a psychological advantage over managers working in local organizations (Beechler et al., 1999). Global identity, in turn, “…encourages managers to think about the firm as a whole and to ignore cultural and other boundaries as appropriate” (Beechler et al., 1999, p. 13). Some researchers (Bartlett & Ghoshal, 1989; Porter, 1986; Prahalad & Hamel, 1994) have contended that managers involved in cross-border dealings would have a better idea of the structures, processes, systems and policies involved in international activities than their counterparts employed in small local businesses. A number of studies have linked global mind-set with global identity (Beechler et al., 1999; Cox, 1994; Ziller, 1973). Beecher et al. (1999, p. 14) explained that “… the cognitive complexity and learning orientation of global mind-set make it possible for managers to grasp the difficult, diverse, highly dispersed operations of the firm, and to understand the differentiated cultural, political, economic and market conditions in which both affiliates and individuals of the firm operate.” In addition, researchers contend that the ability and willingness of managers to think, act and transcend boundaries of values and goals on a global scale requires a global identity and thinking (Bartlett & Ghosal, 1989; Bouquet, 2005; Kanter, 1994).

Global Strategy

A global mind-set is absolutely critical that features on our core competency list. As we grow, we recruit and develop our managers and they need the ability to think globally and act locally, to be sensitive to global issues. (CA8)

Other people in their ways and means, traditions, their philosophies, their way of life—it doesn't matter what it is, you have to be sensitive to that and have a global perspective but understand the ways and means of how business is done overseas. (CA7)

I don't currently work in the US but that's part of my development plan that's been handed to me in terms of my suitability for future roles elsewhere within the company, which, and by elsewhere I mean, you know relocating internationally to work. This deliberate strategy enables me to foster my global thinking and outlook. (US19)

For a manager to be global, he has to be able to benchmark the practices, to be able to gather more opportunities in terms of what will the market need and making sure the organization is in sync with what we want to do. I think this is the challenge. Therefore it's very critical to say you are a global company but also you act, breathe and behave like one. And the way to do that would be for its managers to have a global oriented mind-set. (IN8)

I think it is extremely important I mean if you have to be part of an organization which serves people across different counties and cultures you need to have the ability to think and act as its required. You need to think global and have such a mind-set. (IN13).

So in a day of a manager he does have to spend at least 20–25 per cent of his time thinking at a global level. Although he may be working locally he may be doing things operationally but he still has that percentage of his mind think that “I'm a part of a global organization.” Strategizing on a global scale is an essential part of senior management's responsibility and you need them to have a mind-set that allows that. (IN20)

The comments made by the North American and Indian managers are in support of the view that successful strategy implementation requires visionary senior management to think and act with a common perspective (Bouquet, 2005; Catoline, 1989; McAleese & Hargie, 2004). A number of scholars have contended that a global perspective engendered by organizational imperatives to foster global linkages and accept global challenges is vital to the conceptualisation and implementation of global strategies (Harveston, 2000; Jeannet, 2000; Nummela et al., 2004). Specifically, the relationship between the global mind-set of leaders, and its linkage with multinational and global strategies, has been explored by a number of researchers (Harveston, Kedia, & Davis, 2000; Kobrin, 1994; Levy, 2005). This notion is shared by Prahalad and Doz (1987), who argued that organizational capabilities to exploit complex strategic perspectives to their full potential depend on managerial mind-sets that “… equilibrate integration and responsiveness expectations rather than predispose decisions in favour of one dimension at the expense of the other …” (p. 179). This contention is further strengthened by Murtha et al. (1998), who suggested that “… process theorists have variously specified the direction of relationships between mind-sets and business policies that can leverage international strategic change. Mind-sets confer insight to design appropriate policies …” (pp. 98–99).

Flexibility

For organizations like ours, it's not even a choice—it's almost a conscious thing to have this global mind-set—otherwise, you will not be able to survive in this dynamic environment. (US1)

I don't think we will be able to survive. Not without senior management possessing a mind-set that enables dynamism in thinking. We are in mining and we are constantly challenged by numerous local laws in different places that keep changing. (CA5)

Flexibility is the key. Our senior managers are equipped with a mind-set that allows them to be proactive, rather than reactive to change. Without such a mind-set, one can't take quick and vital decisions in a dynamic [global] market. (US4)

You need to think what is happening globally—that may affect the business and customers. I think businesses are going to have to change depending on what has happened. And you need managers with a global mind-set to understand this. (IN11)

The mind-set has changed in that you have to understand the customer requirements in the country in which we are going to sell starting with culture, quality standards, price requirements and things like that. So mind-set has to change from both sellers and buyers point of view. (IN6)

The global economic crisis, well not crisis yet but a slowdown makes it critical for managers to manager uncertainty well. I guess if senior managers can't adapt or be flexible now in their thinking and in the coming years to deal with the slowdown, their organization might not survive let alone be competitive. For us, senior managers need to understand this and have a mind-set that can negotiate this. (IN2)

The comments by the North American and Indian managers are supportive of the literature on strategic flexibility. Indeed, managerial flexibility is an essential outcome of a global mind-set, as it enables global managers in global business organizations to understand the nature of international business in different contexts, to appreciate the need for diverse approaches and systems, and to operate in dynamic environments (Bouquet, 2005; Bowen & Inkpen, 2009; Calori, Johnson, & Sarnin, 1994).

Sustainable Approach to Business

Being able to sustain our business is the key. Every manager has to work towards that. (US1)

You need senior leaders who can take decisions and change their thinking—as per the situation in order for an MNC like ours to sustain. (CA5)

We cannot be thinking unidimensionally all the time—I mean that defeats the whole idea of globalization—we are a global firm and our senior leaders need to have a mind-set that comprehends survival, competition and embracing multidimensionality. (US18)

The global mind-set means being able to look at the bigger picture and cater for the customers. (IN14)

People who need to distinguish themselves from their own geographies I'm sure they can do well with whatever. They do need to possess this mind-set. There are equal and ideal opportunities. They need to know how to react in different economies and geographies, how to sustain the business. (IN1)

Especially in this climate you know, we need sustainable business strategies more than ever. We need out senior management to rethink their strategies, change their mind-set—with a more sustainability focus. (IN6)

These comments made by both sets of managers provide underpinning for the link between global mind-sets and a sustainable approach to business. Doing business globally inevitably implies long- rather than short-term perspectives, as international business is naturally focused on establishing credible relationships with joint venture and strategic alliance partners, negotiating the mazes of local and international legislation, and being responsive to dynamic market changes (Jones & Millar, 2010). Global mind-sets enable managers to appreciate the importance of a long-term sustainable approach to the management of organizations which in turn requires versatile and balanced approaches combining global effectiveness with local values, compliance, and responsiveness (Govindarajan & Gupta, 2002; Jones & Millar, 2010; Paul, Meyskens, & Robbins, 2011; Thomas, 2006). Rogers and Blonski (2010, p. 19) explained that “a global mind-set includes the ability to see beyond the boundaries of the organization, national culture, functional responsibilities and corporate gain to envision and communicate the ultimate contribution and value of the work to society and sustainability.”

Diversity Appreciation

Cultural sensitivity is a vital competency. Perhaps if we all had global mind-sets and were open to differences, it's much easier for the firm as a whole. (CA7)

You have got to appreciate diversity in every country you operate including your home country. (US10)

So, unless you have that global mind-set, understanding of different cultures, I don't think you can do it successfully. (US6)

So it is important that the manager is aware or open to those types of ideas or else he is surely bound to have trouble. Maybe as a boss or a subordinate he has to be open to these ideas I mean there are differences in culture and clashes in the way we do things and if we are to iron them out you have to be open minded. (IN16)

Even as an organization it has taken us time to adjust to different cultures because we may have our own different mind-set so if senior management doesn't have a mind-set they will not be able to train the junior level with the right mind-set. So according to me a global mind-set is very important for any organization or industry that has international customers but also those solutions or products that they offer will have a wider application globally. (IN3)

This global mind-set does work in the long run. The skill sets that you build up over the years can be used across borders where diversity is an issue. (IN12)

The above comments provide support to the notion of diversity appreciation as an outcome of a global mind-set. Indeed, diversity appreciation and management has been a pervasive theme in the international management literature for several decades now, embracing both its multicultural and more individualized managerial elements (Calori et al., 1994; Perlmutter, 1969; Thomas, 2006). Accordingly, global mind-sets inherently assume that global managers are aware of cultural, social, and personal differences, and are able to understand, appreciate, and adapt to them as required in diverse contexts (Arora et al., 2004; Govindarajan & Gupta, 2001; Javidan et al., 2011; Lovvorn & Chen, 2011; Taylor et al., 2008). Moreover, Beechler and Javidan (2007) explained that a global mind-set helps foster leadership in diverse cultural involvements. In addition, Levy et al. (2007b) explained the importance of global mind-set in facilitating cultural adaptability, which is vital in a diverse cross-border business environment.

Discussion

The qualitative results and the earlier literature review provided underpinning for the conceptualization of the outcomes of a global mind-set, with benefits for the global managers themselves and the multinational corporations that they represent, and they are summarized in Figure 1. While it was expected that the different contexts from which the interviewees were derived might present identifiable differences in emphasis and priorities between the North American and Indian senior managers in this study, there are far more similarities than differences in their responses, reflecting a homogeneity in their perspectives of the outcomes and benefits of a managerial global mind-set. It was expected that representatives of such multinational corporations (Sealy et al., 2010) would embrace the challenges and opportunities available in diverse contexts and marketplaces, and be able to articulate their approaches to them, and this is certainly evident from their responses. A significant underlying theme from the respondents was the crucial alignment of organizational and managerial global views in terms of the importance placed on managerial global mind-sets (Bartlett & Ghoshal, 1998; Kefalas, 1998; Perlmutter, 1969; Prahalad & Doz, 1987). Five dimensions and their outcomes of global mind-sets were derived through the qualitative analyses. They include global identity, global strategy, flexibility, sustainable approaches to business, and diversity appreciation, and have significant implications for multinational corporations especially in relation to management development (“Training for Success,” 2009; Bhatnagar, 2006).

Global identity (Govindarajan & Gupta, 2001; Jeanett, 2000; Rhinesmith, 1993) was perceived in both organizational and individual terms—it is advantageous on one hand for employer branding and international service quality, while on the other hand it also benefits particular managers through growth and career development opportunities. Global identity was considered a vital outcome of a managerial global mind-set and was perceived as a shared concept between organizations and their managers, with mutual benefits (Beechler et al., 1999; Cox, 1994; Ziller, 1973). This linkage can be fostered, developed, and reinforced through a variety of activities, including managerial selection, learning and development, and global rotation programs with increased exposure to global business activities. Similarly, managerial global mind-sets were linked by the respondents to the formulation of global strategy (Bartlett & Ghoshal, 1989, 1998; Harveston, Kedia, & Davis, 2000; Heenan & Perlmutter, 1979; Kobrin, 1994; Levy, 2005), which was perceived as a “core competence” of organizations and their individual managers, leading to global benchmarking business systems and the capacity to balance global imperatives with local influences (Kobrin, 1994; Srinivas, 1995).

Several managers from both North America and India referred to the need for global business organizations to be “strategically agile” (Doz & Kosonen, 2008, 2010; Young, 2008) in order to prosper and grow in dynamic global marketplaces through differentiated policies and business systems, and for managerial flexibility with respect to the diversity of global markets, cultures, customers, products and markets (Calori et al., 1994). The managers provided anecdotal evidence of the link between managerial global mind-sets and strategic agility and flexibility at the organizational level. Moreover, diversity management has been considered vital for organizational success in the global arena (Arora et al., 2004; Calori et al., 1994; Govindarajan & Gupta, 2002; Javidan et al., 2011; Lovvorn & Chen, 2011; Perlmutter, 1969; Taylor et al., 2008), with an emphasis on deep cultural understanding of multiple international constituencies, and the associated managerial competencies, including uncertainty acceptance, inquisitiveness, “cultural intelligence” (Thomas, 2006), and acceptance of complexity (Ananthram et al., 2010; Rhinesmith, 1992; Srinivas, 1995). Initiatives such as cultural sensitivity training, global rotation schemes and multicultural project teams (both actual and virtual) can be utilized to enhance these managerial competencies.

Many of the managers interpreted managerial global mind-set as an enabler of organizations adopting a sustainable approach to business. This was interpreted as the organizational (and managerial) capacity to focus on “the big picture,” and to project a positive business image (or employer brand) for growth purposes; whilst simultaneously transferring knowledge and sharing technology, and acting as a “global citizen” with its accordant moral values and social responsibilities (Nummela et al., 2004; Paul et al., 2011; Rogers & Blonski, 2011; Thomas, 2006). In addition, managers agreed with the need for a global mind-set which embraced the long-term sustainability (rather than the short-term business goals) of their organizations, with several suggesting the need for “situational leadership,” which integrated long-term and short-term business plans, complemented with contingency options (Govindarajan & Gupta, 2002). The views of both North American and Indian managers coalesced here, despite suggestions from the associated literature (Todd & Javalgi, 2007; Yip et al., 1997) that US multinationals tend to have shorter-term perspectives than their Indian counterparts.

In addition, both North American and Indian managers also suggested that it was imperative for lower-level managers and other employees to also possess a global mind-set in order for the organization to reap its cross-border business advantages vis-à-vis their global competitors. The role of effective management development systems and integrated employee training programs is important in helping managers including executives to develop global mind-sets and associated skill-sets and competencies (Bhatnagar, 2006). The development of global mind-sets is amenable to customized management enhancement programs which combine “positive intercultural personality characteristics and positive self-adjustment” (Furuya, Stevens, Bird, Oddou, & Mendenhall, 2009, p. 202) with individual learning, mentoring, and ongoing organizational support, including appropriate policies and processes. Techniques such as cultural exposure, language training, problem-centered and experiential learning opportunities are invaluable components of such programs (Srinivas, 1995, p. 33).

Implications of the Study

The findings have a number of theoretical and managerial implications. The article contributes to existing global mind-set theory in three ways. First, it fills a gap in the literature on global mind-set development which has predominantly focused on the antecedents and characteristics of a global mind-set, by identifying its outcomes and benefits. Second, the article explores global mind-sets and their outcomes from the perspectives of senior managers of multinational corporations in two dissimilar cultural contexts—namely, North America and India—thereby providing an opportunity for comparisons of its applications. Third, the findings from the study have enabled the development of a conceptual framework that classifies the key outcomes of a global mind-set for multinational corporations and their global managers, especially senior executives. Future researchers are encouraged to empirically validate and extend this framework by testing it across different national and industry contexts with global managers at different levels in multinational corporations.

These outcomes also have significant practical implications for multinational corporations and their senior managers, as well as for their human resource professionals. Organizations might use the research findings to assist in the design of their global talent attraction and retention policies and strategies. In addition, potential and existing senior executives could identify their strengths and development needs in relation to future assignments; and HR professionals may factor the expected outcomes of global mind-sets into their applicant selection, management development, performance review and compensation programs, in helping to build intelligent global organizations. In combination, these programs can assist in the cultivation and nurturing of global mind-sets among senior executives and managers, with significant demonstrable benefits for multinational corporations.

Limitations and Conclusion

In summary, the findings reported in this article reinforce earlier research suggesting that the concept of a global mind-set is complex and multifaceted. Using an exploratory qualitative methodology, this article highlights the importance of a managerial global mind-set, and delineates its dimensions, outcomes and benefits for managers themselves and the multinational corporations that they represent. There were interestingly, few significant differences between the North American and Indian managers, possibly due the nature of their organizations and the level of managers interviewed. The findings of the study, however, have their limitations due to the relatively small sample, its emphasis on senior managers alone, and its qualitative focus. It might also be argued that a comparison between North American and Indian senior managers’ perceptions is limited, and that global studies would yield more valid findings. We would encourage subsequent researchers to undertake more comprehensive studies. Future research might include larger-scale mixed method studies that include managers across various levels in different national contexts in order to provide more representative findings for the outcomes and benefits of a global mind-set, in order to validate and extend the framework presented in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Associate Professor Richard Grainger and Dr. Bella Butler for their assistance in the research design.

Biographies

Dr. Subramaniam Ananthram is a senior lecturer in international business at Curtin Business School, Curtin University, in Perth, Australia. His research interests include international strategic management, global mind-set development and international human resource development.

Dr. Alan R. Nankervis is an adjunct professor of HRM at Curtin Business School, Curtin University, in Perth, Australia. He has previously worked at universities in Sydney, Melbourne, United Kingdom, Canada, Singapore, Thailand, and Indonesia. He is the author or coauthor of more than 150 publications. His research interests include comparative Asian HRM/management, strategic HRM, services management, and performance management.