A case of metastatic adenoid cystic (basal cell) carcinoma of the prostate: Systemic therapy for a rare disease

Abstract

Background

Metastatic adenoid cystic (basal cell) carcinoma of the prostate is an exceedingly rare disease entity. As a result, no current consensus exists for optimal systemic therapy.

Methods

We present a patient with metastatic adenoid cystic (basal cell) carcinoma of the prostate who subsequently received systemic treatment, including chemotherapy and immunotherapy. We comprehensively reviewed all published data on therapy outcomes in advanced disease.

Results

Our patient benefited from combination chemotherapy (carboplatin and paclitaxel), with objective radiographic response and reduction in cancer-related pain. However, chemotherapy was stopped due to cumulative neurotoxicity, and subsequent immunotherapy with atezolizumab did not produce any response. Our literature review revealed inconsistent outcomes with various treatments but showed most promise with chemotherapy. Targeted therapy and immunotherapy seem to benefit specific cases, and androgen deprivation therapy had minimal evidence of benefit.

Conclusion

Based on the findings of our case report and literature review, we suggest platinum-based chemotherapy doublets as first-line treatment for metastatic cases of adenoid cystic (basal cell) carcinoma of the prostate, reserving targeted therapy or immunotherapy for select cases based upon molecular profiles.

1 INTRODUCTION

Adenoid cystic (basal cell) carcinoma of the prostate is an extremely rare type of prostate cancer, as fewer than 150 cases have been reported.1 While previously thought to exhibit an indolent course, recent evidence shows that its progression varies and nearly 25% of patients develop local recurrence or distant metastasis.1-3 However, there is a paucity of data regarding outcomes with systemic therapy in advanced-stage cases. Strategies to palliate these patients are very poorly defined. Here, we present a case of a patient with metastatic prostatic adenoid cystic (basal cell) carcinoma who demonstrated a positive response to chemotherapy and propose a possible treatment paradigm.

2 CLINICAL CASE PRESENTATION

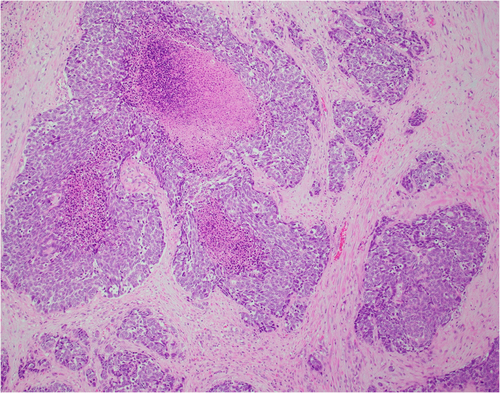

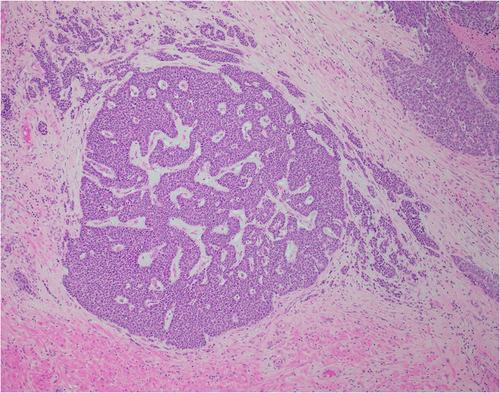

An 80-year-old male initially presented with obstructive urinary symptoms and underwent a simple prostatectomy. Pathology from that procedure revealed adenoid cystic (basal cell) carcinoma of the prostate with extensive involvement of the gland (approximately 85%). The tumor displayed an ill-defined focal cribriform pattern with an extensive solid nested pattern with basaloid cells and areas of comedonecrosis (Figures 1 and 2). Immunostaining revealed the tumor cells to be positive for Bcl-2, high molecular weight cytokeratin, and p63 (focal) and negative for PSA, synaptophysin, and chromogranin A, consistent with adenoid cystic (basal cell) carcinoma.3-5

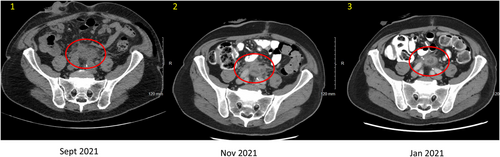

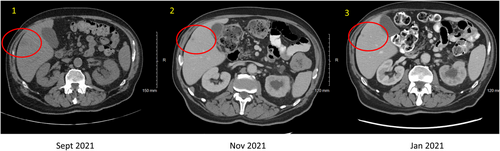

Ultimately, the patient underwent a palliative radical cystoprostatectomy due to further voiding dysfunction. The postsurgical pathology further demonstrated adenoid cystic (basal cell) carcinoma of the prostate as a locally aggressive and infiltrative tumor with peritoneal implants. Subsequent whole-body imaging showed left-sided hydronephrosis due to ureteral obstruction from a soft tissue mass at the iliac bifurcation (Figure 3), multiple metastatic hepatic lesions (Figure 4), and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy.

On presentation to medical oncology, he was noted to have an ECOG Performance Status of 2, secondary to significant cancer-related pelvic pain. Initial impression was metastatic adenoid cystic (basal cell) carcinoma of the prostate to viscera (liver) with locally invasive symptomatic disease despite aggressive palliative local therapies. Prognosis was guarded. He was initiated on an analgesic and supportive care plan including referral to palliative care. Systemic therapy to address the underlying progressive malignancy causing the symptoms was needed.

The tumor was immediately sent for next-generation sequencing. However, given the symptomatic nature of the disease, therapy was imminently needed. Immunotherapy was considered, given case reports of possibility response; however, ultimately empiric chemotherapy was recommended as best option for possible immediate palliative benefit. He was treated with carboplatin AUC 6 and paclitaxel 200 mg/m2. On reassessment after two and four cycles of chemotherapy, he was noted to have improved pelvic pain and a partial response on repeat CT of the abdomen and pelvis. The hepatic lesions were reduced in size (Figure 4), and the pelvic mass had decreased in size (Figure 3). Therapy was discontinued after five cycles due to cumulative neurologic toxicity.

After a 2-month treatment holiday, repeat staging unfortunately showed loss of response with progressive of disease. Next-generation sequencing revealed mutations of ASXL1, CDKN1B, KRAS, PIK3CA, and TSC1 genes (Table 1). Microsatellite status was stable. The tumor mutational burden was four mutations per megabase. The PD L-1 combined positive score (CPS) was 7%. Given the short duration of response after the carboplatin-paclitaxel and cumulative chemotherapy toxicity, immunotherapy with atezolizumab was next trialed noting at least one case report of response in metastatic adenoid cystic (basal cell) carcinoma of the prostate.6 Unfortunately, he experienced primary progression of disease both clinically and radiographically after two cycles of immunotherapy. We next considered targeted therapy given the TSC1 mutation and referred the patient for palliative radiotherapy to the pelvis. While undergoing palliative radiotherapy, he had further clinical decline of his performance status. He was referred to hospice and passed shortly thereafter, ultimately surviving ~11 months since systemic therapy initiation and ~14 months since diagnosis.

| Gene(s) | Alteration | Coding sequence effect | Type of alteration | Variant allele frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASXL1 | R404* | 1210C>T | Substitution—Nonsense | 1.1 |

| CDKN1B | D44fs*27 | 129_131GGA>TG | Deletion—Frameshift | 7.4 |

| KRAS | G12A | 35G>C | Substitution—Missense | 34.0 |

| PIK3CA | E545G | 1634A>G | Substitution—Missense | 32.5 |

| TSC1 | Splice site 509-11_515del18 | 509-11_515del18 | Deletion—Splice Site | 28.3 |

3 PUBLISHED DATA ON SYSTEMIC THERAPY IN ADENOID CYSTIC (BASAL CELL) CARCINOMA

Given the rarity not only of prostatic adenoid cystic (basal cell) carcinoma but particularly of a metastatic presentation, we performed a literature review on relevant studies (Table 2). Medical decision making for this patient was exceedingly difficult, given that our knowledge regarding expectations and outcomes for systemic therapy was limited to a handful of case reports. We sought to identify all reports of outcomes for patients with metastatic prostatic adenoid cystic (basal cell) carcinoma who received some form of systemic treatment (i.e., not just surgery or radiation therapy).

| Systemic therapy | Agent(s) | Site of metastasis | Reported outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemotherapy | Docetaxel and estramustine | Mediastinal and iliac lymph nodes, bone | Progression of bone metastases and development of new lung metastases after two cycles | [5] |

| Carboplatin and etoposide | Pelvis, liver, and lung | Progression of disease in liver and pelvis after two cycles | [6] | |

| Cisplatin and docetaxel | Lung | Progression of disease | [7] | |

| Etoposide | Lung | Partial response (~80% reduction in nodules after 9 months) | [7] | |

| Docetaxel | Bone and liver | Alive ~3 years later | [8] | |

| Chemotherapy and androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) | Carboplatin, paclitaxel, and degarelix | Liver | Decreased size of liver lesion after three cycles | [9] |

| ADT | Goserelin and flutamide | None | Bone metastases 4 months later, hepatic metastases 10 months later | [8] |

| Goserelin and bicalutamide | Lung | Died 5 months later | [8] | |

| Leuprorelin and bicalutamide | Internal iliac and para-aortic lymph nodes | New inguinal lymph node metastasis within 3 months, died within 7 months | [10] | |

| Bicalutamide | “Advanced clinical stage” | No progression of disease 6 months later | [11] | |

| Leuprolide | Lung | Not tolerated and discontinued | [4] | |

| Targeted therapy | Pemigatinib | Liver | Partial response | [12] |

| Olaparib | Lung | Decreased size of multiple lung nodules after 3 months then mixed response after 8 months | [4] | |

| Immunotherapy | Atezolizumab | Lung | Mixed response including disappearance of four nodules but growth of two nodules; pneumonitis | [4] |

| Pembrolizumab | Abdominal wall | Alive 2 years after diagnosis | [13] |

3.1 Outcomes with chemotherapy

The most common form of systemic treatment in the literature was chemotherapy. As expected, success varied significantly across cases. For instance, one patient received a combination of docetaxel and estramustine after evident bone metastasis. After two cycles, a CT scan showed progression of his osseous metastases as well as new lung metastases.7 Another patient with metastases involving his liver and lungs was treated with carboplatin and etoposide. Similarly, imaging after two cycles showed progression of his disease.4

On the other hand, one case details a patient who suffered pulmonary metastases 17 months after initial prostatectomy and radiotherapy. He experienced progression after six cycles of docetaxel with cisplatin added for the final three cycles. However, after switching to and undergoing nine cycles of etoposide, that patient experienced an 80% decrease in the size of his existing lung nodules without development of any new nodules.5 Another patient received docetaxel and has remained alive after nearly 3 years of follow-up.8

3.2 Outcomes with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT)

ADT has similarly demonstrated inconsistent results. The aforementioned patient who received docetaxel did so after hepatic and osseous metastases developed on a regimen of goserelin and flutamide.8 ADT in other patients also proved unsuccessful, consistent with the fact that adenoid cystic (basal cell) carcinoma usually shows little to no androgen receptor expression.14 One patient with pulmonary metastases was started on goserelin and bicalutamide and died shortly after.8 Another patient with metastasis to nonregional lymph nodes received leuprorelin acetate and bicalutamide yet still rapidly deteriorated.10

Still, some moderate success with hormonal therapy has been reported. One patient with advanced cancer was treated with bilateral orchidectomy and bicalutamide. He had no evidence of disease progression after 6 months but was lost to follow-up after.11 A recent case details a patient who received both chemotherapy and ADT in the form of carboplatin, paclitaxel, and degarelix after ex vivo testing of the patient's tumor. After three cycles, his metastatic hepatic lesion decreased in size.9

3.3 Outcomes with targeted therapy

Besides chemotherapy and ADT, a small number of cases have been reported describing other forms of systemic treatment. Targeted therapy with pemigatinib, a fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) inhibitor, and olaparib, a poly ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitor, have demonstrated successful improvement in metastatic lesions in patients whose genetic testing indicated such therapies.6, 12

3.4 Outcomes with immunotherapy

Finally, immunotherapy has rarely been used. The patient who received olaparib had atezolizumab, a programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitor, added in hopes of a synergistic effect with PARP inhibition. This resulted in a mixed response of his metastatic pulmonary lesions as well as drug-induced pneumonitis.6 Another patient with abdominal metastasis was treated with pembrolizumab, a programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) inhibitor, and was still alive 2 years after his diagnosis.13

4 DISCUSSION

Prostate cancer is the leading cause of cancer in men in the United States and the second most in men worldwide.15, 16 The vast majority of cases are acinar adenocarcinomas with 5%–10% of carcinomas classified as nonacinar.17 Adenoid cystic (basal cell) carcinoma constitutes a small portion of the latter, as fewer than 150 cases have been reported. Most commonly found in older men between the ages of 65–84 years, these tumors arise from and are composed of prostatic basal cells and can be distinguished from basal cell hyperplasia by their architectural pattern, high Ki67 index and invasive growth with a desmoplastic stroma. Aggressive behavior is correlated with a solid pattern with necrosis as was seen in our case.2, 12, 17 Contrary to adenocarcinoma, adenoid cystic (basal cell) carcinoma often has a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level within normal range and metastasizes viscerally to liver, lung, and bowel.12, 14

Given the rarity of this form of prostate cancer, no consensus exists for the best systemic treatment in cases of advanced disease. In this report, metastatic lesions showed marked improvement in response to carboplatin and paclitaxel. The findings of our case as well as our literature review, suggest that chemotherapy warrants consideration as a treatment option in future cases of metastatic disease. Specifically, carboplatin-paclitaxel and etoposide are two regimens that have demonstrated success. Alternatively, immunotherapy has also proven successful despite limited data, as has targeted therapy based on genomics. Meanwhile, ADT appears less beneficial.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Given the rarity of this disease, there will likely never be a formal prospective investigation of systemic therapy in advanced disease. The highest level of data that will exist will therefore be limited to these case series and case reports. Reporting of these outcomes for patients with metastatic adenoid cystic (basal cell) carcinoma remains of highest importance to continue to shed light on possible palliative strategies. Based upon this review of available cases, we would suggest that first-line treatment with chemotherapy (platinum doublet) is the current optimal approach. Next-generation sequencing for possible targeted therapy may also be beneficial, as targeted therapy and immunotherapy can be considered based upon the genomics of the tumor. ADT can be reasonably combined with these interventions, but we would propose that it should be discontinued if evidence of progression or if poorly tolerated.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Benjamin A. Teply has served as a paid consultant/advisor to Seagen, Janssen, AstraZeneca, Lilly, and Sanofi; and has served on scientific review panel for Pfizer/Myovant; has received research funding (to his institution) from QED Therapeutics, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Inovio Pharmaceuticals, and Bellicum Pharmaceuticals.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.