Structures of plasmepsin X from Plasmodium falciparum reveal a novel inactivation mechanism of the zymogen and molecular basis for binding of inhibitors in mature enzyme

Pooja Kesari and Anuradha Deshmukh contributed equally to this study.

Funding information: Department of Biotechnology, Ministry of Science and Technology; Michigan Economic Development Corporation, Grant/Award Number: 085P1000817; National Cancer Institute; Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, NIH; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Grant/Award Number: HHSN272201700059C; Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, Grant/Award Number: RGPIN 04598; U. S. Department of Health and Human Services; National Institutes of Health; IIT Bombay; IRCC

Abstract

Plasmodium falciparum plasmepsin X (PfPMX), involved in the invasion and egress of this deadliest malarial parasite, is essential for its survival and hence considered as an important drug target. We report the first crystal structure of PfPMX zymogen containing a novel fold of its prosegment. A unique twisted loop from the prosegment and arginine 244 from the mature enzyme is involved in zymogen inactivation; such mechanism, not previously reported, might be common for apicomplexan proteases similar to PfPMX. The maturation of PfPMX zymogen occurs through cleavage of its prosegment at multiple sites. Our data provide thorough insights into the mode of binding of a substrate and a potent inhibitor 49c to PfPMX. We present molecular details of inactivation, maturation, and inhibition of PfPMX that should aid in the development of potent inhibitors against pepsin-like aspartic proteases from apicomplexan parasites.

Abbreviations

-

- PM

-

- plasmepsin

-

- RBC

-

- red blood cell

-

- Pfpro-PMX

-

- Plasmodium falciparum plasmepsin X with truncated prosegment

-

- Pfm-PMX

-

- Plasmodium falciparum plasmepsin X mature domain

-

- TgASP

-

- Toxoplasma gondii pepsin-like aspartic protease or toxomepsin

-

- UD

-

- uncharacterized domain

1 INTRODUCTION

The phylum Apicomplexa comprises unicellular parasitic protists capable of infecting different animals and mammals. Among these parasites, Plasmodium, Toxoplasma, and Cryptosporidium are of the major global health concern as they infect humans and animals.1, 2 Plasmodium falciparum is the most lethal species in the genus Plasmodium, responsible for human malaria, one of the deadliest diseases worldwide, causing deaths of thousands of people every year.3 Toxoplasma gondii is an obligate intracellular parasite that causes a fatal disease toxoplasmosis.4, 5 Cryptosporidium species cause cryptosporidiosis, the second most prevalent form of infant diarrheal disease.6 Despite the high incidence of these diseases, treatment options are limited due to low efficiency of the available drugs and the continual emergence of resistant strains. For such reasons, there is a pressing need for novel, long-lasting therapeutic agents against different apicomplexan parasites.7-9

Pepsin-like aspartic proteases are involved in nutrient uptake, immune evasion, invasion, and egress, which are vital processes that enable parasites to cause a successful infection inside the host cell. P. falciparum encodes 10 pepsin-like aspartic proteases known as plasmepsins (PMs), PfPMI to PfPMX. Among them, PfPMI, PfPMII, PfPMIV, and histo-aspartic protease (PfPMIII or HAP), also referred to as vacuolar plasmepsins, are responsible for the degradation of host hemoglobin.10 PfPMV acts as a maturase for proteins exported into the red blood cells (RBC) cytoplasm, involved in host cell remodeling.11 PfPMIX and PfPMX are involved in the invasion and egress of the parasite.12, 13 T. gondii encodes seven pepsin-like aspartic proteases called toxomepsins (TgASP1–TgASP7); of which TgASP3 shares 40% homology with PfPMX and carries out a similar function. Invasion and egress, facilitated by proteases like TgASP3 and PfPMX, are two key events essential for survival and dissemination of infection for these classes of parasites; therefore, these enzymes (later referred to as PMX-like proteases) are attractive drug targets.14-18

PMX is located in the small ovoid secretory vesicles known as exonemes, which are discharged during the egress process of the malarial parasites.13 Mature PfPMX acts on exoneme and microneme proteins, such as SUB1, AMA1, reticulocyte-binding protein homologs (Rhs), and erythrocyte binding-like (EBL) proteins that are responsible for both invasion and egress. The Rh2N peptide has been reported to have faster cleavage rate as compared to other known substrates for this enzyme.19 PfPMX is expressed in the blood-stage schizont and merozoite stage; additionally, it is found in the gametocyte and liver stage of infection.12, 13 Like PfPMX, TgASP3 also acts on microneme and rhoptry proteins.15 Furthermore, PfPMX and other similar proteases (PMX-like) from apicomplexan parasites share significant functional and sequence level similarities; hence, understanding the molecular basis of the functional properties of these enzymes would undoubtedly be useful in the development of potent therapeutic agents against these deadly parasitic diseases.

The complete polypeptide of PfPMX is synthesized and folded as inactive zymogen (Pfpro-PMX) consisting of a prosegment and a mature domain (Pfm-PMX). The prosegment of PfPMX is longer than its counterpart in vacuolar plasmepsins and other gastric or plant pepsin-like aspartic proteases.12, 20, 21 In general, activation of the zymogens of pepsin-like aspartic proteases takes place by removal of the prosegment under acidic conditions. It is suggested that vacuolar PMs have an auto-activation mechanism wherein the dimeric form is converted to a monomer under acidic conditions due to the disruption of the Tyr-Asp loop at the pro-mature junction, with subsequent unfolding and cleavage of the prosegment by the trans-activation process.22 Conversely, in other pepsin-like aspartic proteases, the interaction of a lysine residue with the catalytic aspartates is responsible for inactivation of the zymogen, which then detaches from the active site under acidic pH, leading to the unfolding of prosegment followed by cleavage by the same enzyme molecule.20, 23 It has been shown that PfERC (Plasmodium falciparum endoplasmic reticulum-resident calcium-binding protein) protein works at the upstream position in the activation pathway of PfPMX.24 Upon activation, the zymogens of PMX-like proteases form mature enzymes which promote invasion and egress of the parasites. The longer length of the prosegment of PfPMX zymogen indicates a possibility of a novel inactivation mechanism.

Inhibition studies with hydroxyethyl amine compound 49c, a peptidomimetic molecule found to inhibit PfPMIX, PfPMX, and TgASP3, and ultimately the invasion and egress of the parasites by impairing maturation of protein cascade, underscore the importance of these enzymes in parasite survival.12, 15, 18 A previous study showed the importance of a phenylalanine residue from the flap in binding the inhibitor 49c.18 However, detailed analysis of the interactions responsible for binding of substrate and inhibitors in the active site of these enzymes is still lacking. Interestingly, pepstatin A, which is a potent inhibitor of pepsin-like aspartic proteases, does not inhibit PfPMIX and PfPMX12; hence, such observation demands further understanding of the molecular insights into the active sites of these enzymes. No experimental structure for these enzymes has been available so far. Therefore, structural and biochemical studies are needed to investigate the active site architecture, specificity and affinity of the substrates, as well as the inhibitors. Such studies should help in the development of potent lead compounds.

The present study reports the first crystal structure of P. falciparum PfPMX zymogen (Pfpro-PMX) with a truncated prosegment. The prosegment of Pfpro-PMX is folded in a unique way, not observed in any other pepsin-like aspartic proteases. The zymogen exhibits a novel mechanism of inactivation among plasmepsins. Molecular dynamics, as well as structural analysis, elucidate for the first time the detailed molecular basis of substrate-binding to P. falciparum mature PMX (Pfm-PMX) and its inhibition by a potent inhibitor 49c. Molecular details presented in this study should aid in the development of potent inhibitors against PMX-like proteases, with the aim to combat diseases caused by apicomplexan parasites.

2 RESULTS

2.1 Crystal structure of PfPMX zymogen (Pfpro-PMX)

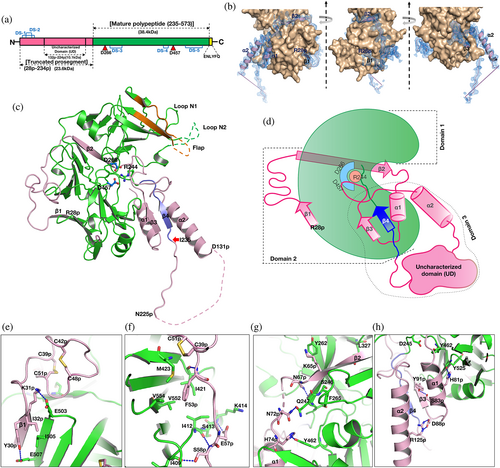

A polypeptide (Figure 1a) of PfPMX, with truncated prosegment (R28p–N234p, where “p” indicates the residues from the prosegment) and TEV cleavage site (ENLYFQ) at the C terminus was crystallized. From here onwards the zymogen obtained from our construct 1 (R28p–N573) is referred to as Pfpro-PMX and the mature enzyme activated or modeled from Pfpro-PMX is referred to as Pfm-PMX (I235–N573). Crystal structure of Pfpro-PMX has been determined at 2.1 Å resolution (Table 1). Figure 1b shows the sigma-A weighted 2Fo–Fc electron density of the prosegment (Movie S1). The first residue (I235) of Pfm-PMX is defined based on its sequence alignment with pepsinogen (Figure S1a). The polypeptide regions with residues K69p–N70p and E132p–K224p in the prosegment and the C-terminal linker region could not be modeled due to lack of features in the electron density. With the exception of a few residues (F308–S315) in the flap, E343–D352 of loop N2, and the last residue N573, the complete mature enzyme portion of the Pfpro-PMX structure could be modeled and refined. An N-acetylglucosamine molecule is visible in the well-defined electron density (Figure S2), indicating that the protein was glycosylated during its expression.

| Data collection statisticsa | Pfpro-PMX |

|---|---|

| Space group | C 2 |

| Unit cell parameters | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 192.30, 50.88, 49.92 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 93.15, 90 |

| Temperature (K) | 100 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.97872 |

| Resolution (Å) | 40–2.10 (2.20–2.10) |

| Rmerge (%) | 4.6 (120.4) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.8 (99.6) |

| Mean I/σ (I) | 15.4 (1.1) |

| Total reflections | 112,116 (7462) |

| Unique reflections | 28,381 (2079) |

| Redundancy | 4.0 (3.6) |

| B factor from Wilson plot (Å2) | 32.6 |

| No. of molecules in the asymmetric unit | 1 |

| Refinement statistics | |

| Resolution (Å) | 35–2.1 |

| Working set: no. of reflections | 28,299 |

| Rfactor (%) | 20.6 |

| Test set: no. of reflections | 2,120 |

| Rfree (%) | 23.8 |

| Protein atoms | 3,225 |

| Geometry statistics | |

| R.M.S.D. bond distance (Å) | 0.007 |

| R.M.S.D. bond angle (°) | 0.800 |

| Isotropic average B-factor (Å2) | |

| Protein | 70.14 |

| Ramachandran plot (%)b | |

| Allowed regions | 96.22 |

| Generously allowed regions | 3.78 |

| Disallowed regions | 0 |

| PDB ID | 7RY7 |

- a Values in parentheses correspond to the highest resolution shell.

- b Ramachandran plot statistics based on MolProbity.

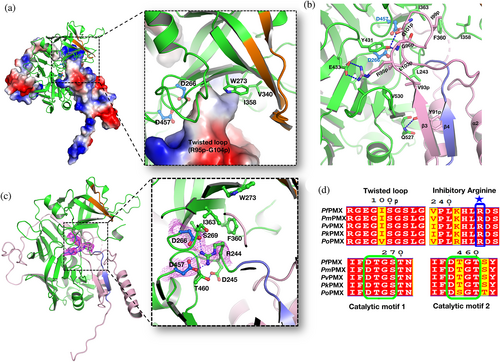

The overall fold of the prosegment of Pfpro-PMX (Figure 1c) is unique and such an arrangement of the prosegment has not been observed before for any other zymogens of pepsin-like aspartic proteases. The prosegment wraps around the elongated bean-shaped mature enzyme (Figure 1c, d). The structure of Pfpro-PMX can be divided into three segments: domain 1 (F248–D391), domain 2 (R28p–K68p and P392–K572), and domain 3 (P71p–Q247) (Figure 1d). Domain 3 also consists of an “uncharacterized domain” (UD) which contains ~90 residues (E132p–K224p) and is not visible in the crystal structure. The prosegment is folded into the first β-strand (β1, R28p–I32p), followed by an extended loop, the second β-strand (β2, S59p–L66p), an α-helix (α1, H74p–K85p), the third β-strand (β3, D88p–N94p), a second loop with a twisted conformation, the second long α-helix (α2, M114p–D131p), and finally an extended loop that connects to the mature part of the protease. The prosegment is stabilized by the mature domain of Pfpro-PMX through several polar and hydrophobic interactions (Figures 1e–h). In addition, the curved confirmation of the first loop region between β1 and β2 of the prosegment is stabilized by two disulfide linkages formed between C39p and C51p, as well as C42p and C48p (Figure S1b). Part of the prosegment (R95p–G104p) is folded in a unique twisted conformation (twisted loop), which then blocks the S1′ and S2′ pockets of the active site (Figure 2a). The C-terminal part of the twisted loop surrounds the initial segment (P239–K241) of the mature polypeptide. A salt bridge between the side chains of R95p and E433 stabilizes the initial part of this loop. The side chains of I99p and L103p are packed in the hydrophobic pocket formed by the flap region of the mature segment (Figure 2b).

The first five residues (I235–P239) of the mature polypeptide form a β-strand (β4) parallel to the β3 of the prosegment. Further downstream the mature peptide is extended into the active site that is stabilized by several interactions with the main chain and side-chain atoms. One notable interaction in the initial part of the mature region is the formation of a salt bridge by R244 with the carboxylate groups of the catalytic aspartates (D266 and D457) (Figure 2c). Sequence comparison also reveals that R244 is highly conserved in PMXs from other malaria-causing parasites (Figure 2d). The flap of the zymogen is in an open conformation due to folding of the twisted loop of the prosegment that occupies the active site region. Two other loops, N1 and N2, also assume an open conformation, likely due to the folding of the polypeptide that connects the second β-strand and the first α-helix of the prosegment (Figure 1c). Apart from the two disulfide linkages in the prosegment, Pfpro-PMX structure has three more disulfide bridges in the mature domain (Figure S1b). Two disulfide bonds (C279–C284 and C482–C521) are similar to those observed in structures of other plasmepsins and pepsin-like aspartic proteases. The disulfide bond formed by two adjacent cysteine residues (C447–C448), present in the Pfpro-PMX structure (Figure S1c) has not been previously reported for any other pepsin-like aspartic proteases. Sequence alignment shows that five disulfide bonds observed in the Pfpro-PMX structure should be conserved in other PMXs from parasites that cause malaria in humans (Figure S3a).

Analysis of the arrangement of the protein molecules in the crystals reveals that Pfpro-PMX forms an “S” shaped dimer, also observed in zymogens of other vacuolar PMs.22 The loop region of the prosegment consisting of residues N225p–K232p is swapped between the two adjacent monomers of the dimer (Figure S3b, c). Five residues (T227p–T231p) of one monomer form a β-strand that results in the formation of anti-parallel β-sheets by pairing with the first β-strand of the mature polypeptide of another protomer. It is not clear whether such a dimer would form in presence of the UD, which in the current structure is not visible. The UD from different PMXs exhibit variable lengths and very low sequence similarity. However, the sequences without UD are highly conserved, indicating that the PMX zymogens from different malaria-causing parasites might have similar overall structures, with the twisted loop from the prosegment and arginine (R244) from the mature peptide blocking the active site (Figure S3a).

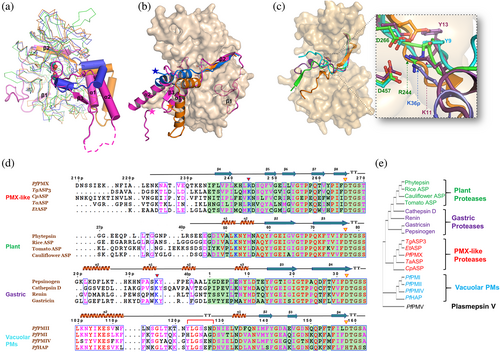

2.2 Structural comparison of Pfpro-PMX with zymogens of other pepsin-like aspartic proteases

Pfpro-PMX has been compared with the representative zymogen structures of other pepsin-like aspartic proteases from parasites, plants, and animals. Previously reported crystal structures of the truncated zymogens of P. falciparum vacuolar plasmepsins (PfPMII, PfHAP, and PfPMIV) reveal that their prosegments have an initial β-strand, followed by two α-helices connected by a turn and a coiled extension with the characteristic “Tyr-Asp” loop that connects to the mature segment of the enzyme.22 The prosegment of the plant and gastric pepsin-like aspartic protease zymogen comprises the first β-strand, followed by two α-helices, a short α-helix, and a turn connecting to the mature domain of the enzyme.

Superposition of the Pfpro-PMX structure with the structures of pepsinogen (3PSG, representing plant and gastric pepsin-like aspartic protease zymogens) and PfPMII zymogen (1PFZ, representing vacuolar PM zymogens) shows that the folding of its prosegment is remarkably different as compared to the latter structures (Figure 3a, Movie S2). Pfpro-PMX has a much longer prosegment than the other pepsin-like aspartic protease zymogens (Figure S1a). The β2 of Pfpro-PMX occupies the same position as the first β-strand of pepsinogen and PfPMII zymogen structures (Figure 3b) and the remaining secondary structure elements have different orientations. The α1 of Pfpro-PMX points downwards, occupying the same space as the tip of a loop in PfPMII zymogen (115p–126p) and pepsinogen; hence, a similar loop is absent in the Pfpro-PMX structure. This loop of vacuolar PM zymogens plays an important role in their activation mechanism22; the absence of such structural element in Pfpro-PMX may imply a different mechanism of maturation. The next secondary structural elements in pepsinogen and PfPMII zymogen are α-helices pointing in two different directions; in Pfpro-PMX it is a β-strand. The last part of the prosegment in pepsinogen forms a short helical turn that provides a lysine residue blocking the active site aspartates; an equivalent position is partly occupied by the twisted loop region of Pfpro-PMX. In vacuolar PM zymogens, the second α-helix is involved in formation of the inter-dimer contacts and the “Tyr-Asp” loop keeps the prosegment in a strained conformation.22 Inactivation of vacuolar PM zymogens is achieved by the prosegment that acts as a harness separating the two domains of the enzyme, resulting in distancing of the catalytic aspartates. High sequence conservation of the twisted loop region (R95p–G104p) among PMX zymogens from other malaria-causing parasites (Figure 2d) implies homology in their structural features. The sequence and phylogenetic analysis (Figure S4a,b) of the UD reveals that this region might be of plant origin and its structural superposition shows that this region may occupy a similar space to that observed for the plant-specific insert in phytepsin zymogen structure (1QDM). However, only determination of the crystal structure of Pfpro-PMX with this domain visible would confirm the actual fold and 3D arrangement of this insertion region. The pro-mature cleavage site (between N234p and I235) of Pfpro-PMX is distal from the active site as seen in vacuolar plasmepsin zymogens, whereas the cleavage site of pro-mature region is adjacent to the catalytic aspartates in the zymogens of plant and gastric pepsin-like aspartic proteases.

A sequence alignment and superposition of homologous modeled structures of other PMX-like protease zymogens from different apicomplexan parasites reveals that these proteases should also assume similar structural folds, with two characteristic disulfide bridges in the prosegment along with the blocking of the active site by a twisted loop (Figure S5a,b). The folding of the initial segment of the mature peptides in the zymogen structure of pepsin-like aspartic proteases are quite different (Figure 3c). The first part (I235–K241) of the mature polypeptide of Pfpro-PMX structure forms a β-strand parallel to the β3 of the prosegment. The polypeptide that connects the first and second β-strands of the mature enzyme is extended, with R244 forming salt bridge interactions with the two catalytic aspartates (Figure 2c). PMX-like proteases from other parasites also have arginine or lysine at the same position, forming salt bridge interactions with the catalytic aspartates (Figure S5a,b). Blocking of the catalytic aspartates by R244 from the mature polypeptide is unique to Pfpro-PMX. Although a lysine residue in the phytepsin zymogen (K11 from mature polypeptide, 1QDM) and pepsinogen (K36p from prosegment, 2PSG) is blocking the catalytic aspartates, there is an additional tyrosine residue (Y13 in 1QDM; Y9 in 2PSG) which also forms a hydrogen bond with the catalytic residues (Figure 3c, d, Movie S3), but the latter is absent in PMX-like proteases or in vacuolar PM zymogens. Further analysis of the full-length sequence-based structural alignment of different pepsin-like aspartic protease zymogens also places PMX-like proteases close to the plant and gastric proteases (Figure 3e).

2.3 Modeling of the structure of mature Pfm-PMX and its complex with a substrate

A model of the mature enzyme, Pfm-PMX (Figure 4a) was developed. The accuracy and the stability of Pfm-PMX structural fold are supported by MD simulation of the structures with and without inhibitors (Figure S6a–d). Pfm-PMX has pepsin-like aspartic proteases fold with two topologically similar N- and C-terminal domains, but with some striking differences as compared to the enzymes belonging to the same family. The N-terminal domain has a β-hairpin-like structure referred to as the flap (I303–T322). One notable substitution in Pfm-PMX is F311, located in the tip of the flap. An equivalent position in other pepsin-like aspartic proteases (except HAP) is occupied by a conserved tyrosine residue (Y77 in pepsin) which, upon substrate binding, forms a hydrogen bond with a tryptophan residue (W41 in pepsin) due to flap closure, thus, initiating a proton relay to maintain the protonated state of the N-terminal catalytic aspartate.25 Presence of F311 in the case of Pfm-PMX would change the opening and closing dynamics of flap, implying a modified mechanism of catalysis without the assistance of a tyrosine. The mature part of Pfm-PMX has three disulfide bonds between residues C279–C284, C447–C448, and C482–C521; whereas vacuolar plasmepsins usually have only two disulfide bonds (C45–C50 and C249–C282 in PfPMII). Due to formation of the disulfide C482–C521 in Pfm-PMX, the peptide region from residues H478–K492 which has a short loop and helical conformation is stabilized (Figure S7a). An equivalent disulfide bond is not observed at the same location in other pepsin-like aspartic proteases.

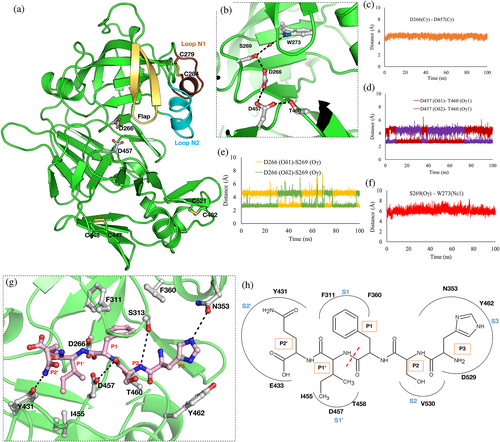

Analysis of the MD simulation run of the Pfm-PMX-Apo provides insights into the active site architecture (Figure 4b) of the enzyme. The Cγ atoms of the carboxylate groups of D266 and D457 are at a distance of around 6.0 Å (Figure 4c), indicating the proximity of these two residues that are needed for catalytic competence. However, carboxylate groups of these two catalytic residues seem to rotate during simulation. The carboxylate group of D457 forms a hydrogen bond with the Oγ1 atom of the T460 side chain (Figure 4d). Also, the Oγ atom of the side chain of S269 is in a constant hydrogen-bonding distance from the carboxylate group of the catalytic D266 (Figure 4e) and around 6.0 Å away from the Nε1 atom of W273 (Figure 4f). All these distances are similar to the corresponding distances reported for the crystal structures of other pepsin-like aspartic proteases. The presence of a water molecule near the carboxylate group of D457 during the MD simulation also confirms its ability to act as a base during catalysis, as in other pepsin-like aspartic proteases. The side chains of W273 and S269 form a water-mediated interaction which is also extended to D266 somewhat similar to other pepsin-like aspartic proteases. The structure of Pfm-PMX indicates that a proton relay from W273 can occur and aid in catalysis even without the help of the flap tyrosine residue.

To decipher the molecular basis of substrate recognition by Pfm-PMX, the peptide Rh2N with the cleavage site (P3HSF/IQP2’)19 sequence was docked into the protein active site and the complex was simulated. The results indicate that the substrate is oriented in a conformation with the phenylalanine at P1 occupying the S1 hydrophobic pocket formed by the flap as well as by loops N1 and N2 (Figure 4g, h, Movie S4). The amide backbone atom of phenylalanine (P1) is hydrogen bonded to D457 and its carbonyl group is pointing toward D266. The side chain of the serine (P2) points away from the flap and its amide backbone interacts with the side chain of the flap S313. Histidine (P3), the N-terminal residue of the substrate, occupies the S3 pocket of the protein formed by residues N353, Y462, and D529. The Nε2 atom of the P3 histidine interacts with the side chain of N353 of loop N2. The side chain of glutamine (P2′) at the C-terminal end makes an interaction with Y431 (Figure 4g, h, Movie S4). Most of these residues interacting with substrates are conserved among the PMX-like aspartic proteases implying a similar mode of substrate binding in these enzymes.

2.4 Removal of the prosegment of Pfpro-PMX to form mature Pfm-PMX

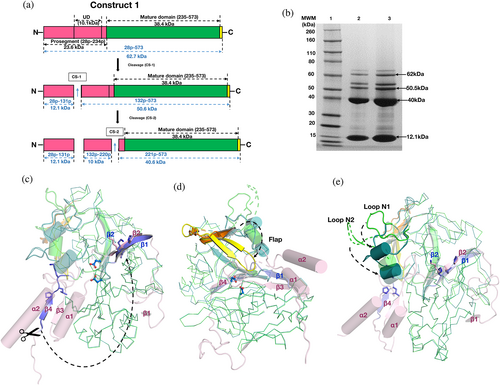

The full-length polypeptide (~65 kDa) of PfPMX zymogen is longer compared to other vacuolar PM zymogens (Figure S1a), and it also has a UD (10.1 kDa) inserted into the prosegment (Figure 1a). A construct (construct 1, R28p–N573 with prosegment R28p–N234p) of Pfpro-PMX, expressed a fusion protein (Figure 5a) with MW ~62 kDa in Expi 293 GnTI-cells and analysis of the eluted protein fractions shows four distinct bands corresponding to the molecular weights of ~62 (full length), ~50.5, ~40, and ~ 12.1 kDa (Figure 5b). N-terminal sequencing of the ~40 kDa band indicated that the putative mature domain begins at L221p and the ~12.1 kDa fragment starts at R28p. Similar pattern of cleavage was also observed when another construct (Construct 2, N190p–N573 with prosegment N190p–N234p) expressed a fusion protein with MW ~61.2 kDa in E. coli (Data S1). These results suggest that the maturation of PfPMX zymogen occurs via cleavage of the prosegment at multiple cleavage sites (CS-1 and CS-2).

Comparison of the crystal structure of Pfpro-PMX with the model of Pfm-PMX reveals that the maturation process of PfPMX zymogen would occur with significant structural changes in the protein (Movie S5). Upon cleavage of the prosegment, the β4 (I235–K241) of the zymogen folds upward to form the first β-strand (β1) of the mature enzyme. Notably, a tripeptide stretch of β1 of the mature enzyme with the sequence P239–L240–K241 is identical to the sequence P63p–L64p–K65p, which is located in the β2 of the prosegment. This indicates a possibility that the β1-strand (P239-L240–K241) of the mature enzyme will occupy the same position as that of the β2-strand (P63p–L64p–K65p) of the zymogen (Figure 5c). After the disruption of the salt bridge with the catalytic aspartates, R244 forms a cation-π interaction with the side chain of Y357 from the loop N2, as we observed in our experiment (Figure S7b). R244 and Y357 are also conserved, indicating the presence of such interactions in PMXs from other human malarial parasites (Figure S3a). Removal of the prosegment creates free space, and, as a result, the flap adopts a closed conformation (Figure 5d) with loops N1 and N2 moving downwards (Figure 5e). Such conformational changes involving these secondary structure elements are also observed in other pepsin-like aspartic proteases. Implications of these regions for inhibitor binding have been discussed in the subsequent sections.

2.5 Mode of binding of 49c in the Pfm-PMX active site

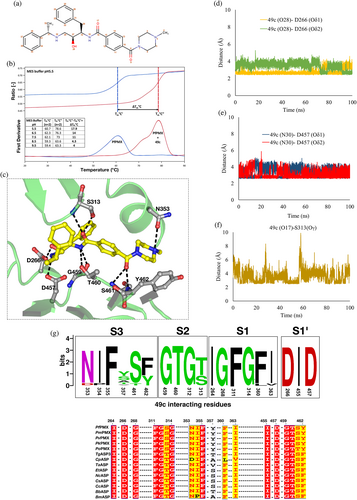

The compound 49c (Figure 6a), containing a hydroxylethylamine scaffold, was designed as a peptidomimetic inhibitor of plasmepsins26 and is reported to inhibit PfPMX.12, 18 The effect of 49c on PfPMX stability at different pH conditions was monitored using nanoDSF (Figure 6b). Difference in melting temperature (ΔTm°C) of Apo- and 49c bound PfPMX suggests that the binding of 49c increases thermal stability of the enzyme. Sequential dip in the difference in melting temperature (ΔTm°C) is observed with an increase in pH, with the highest ΔTm°C observed at pH 5.5, suggesting that binding of 49c is pH dependent.

To understand the molecular basis of the binding of 49c to Pfm-PMX, the compound was computationally docked into the enzyme active site and the inhibitor-bound complex was simulated. Here we present, for the first time, a detailed picture of the interactions of 49c with Pfm-PMX (Figure 6c). Several polar and hydrophobic interactions stabilize the binding of 49c in the active site of Pfm-PMX (Movie S6). The inhibitor binds in a conformation such that its phenylalanine group occupies the S1 pocket, making π–π stacking interactions with F311, similar to those observed for the substrate (Figure S8a). The central hydroxyl group of the inhibitor points toward D266. As the phenylalanine group of 49c mimics the P1 group of a substrate, inhibitors with identical or similar groups at this position could possibly have a binding mode similar to 49c or the substrate. The 49c interacts with the catalytic aspartates D266 and D457, as well as with the residues (F311–G314) from the tip of the flap (Figure S8a). The carboxylate group of D266 is in constant hydrogen bonding with the hydroxyl group (atom number 28) of phenylalanine moiety (Figure 6d) and the carboxylate group of D457 side chain is interacting with the N30 atom of the phenylethylamine moiety of 49c (Figure 6e). Also, the carbonyl group of benzamide (O17) interacts with S313 from the flap during most of the time of simulation, holding the flap in a closed state (Figure 6f). Hydrogen bonding of D266 and D457 carboxylate groups with the hydroxyl groups of the nearby residues S269 (Figure S8b) and T460 (Figure S8c), respectively, hints at the correct geometry of the catalytic residues in the inhibitor-bound state. Based on sequence analysis, it appears that the residues which are involved in binding of 49c in the active site of Pfm-PMX are also conserved or similar (Figure 6g) among PMX-like proteases from various apicomplexan parasites. Therefore, it is likely that 49c would inhibit PMX-like proteases and arrest invasion and egress processes in apicomplexan parasites. Such molecular insights unraveling the interactions of 49c with Pfm-PMX would allow development of potent inhibitors for PMX-like proteases.

Although our data suggest that Pfm-PMX active site can accommodate inhibitors which are transition state mimics with a central hydroxyl group, notably this enzyme is not inhibited by pepstatin A, a potent inhibitor of a majority of pepsin-like aspartic proteases.12 Structural superposition of Pfm-PMX and pepstatin A-bound PfPMII (1M43) shows that the ligand-binding pocket in both proteases is quite dissimilar (Figure S9). The presence of Y462 in Pfm-PMX, compared to A219 in PfPMII, narrows the binding pocket, leading to possible steric hindrance and blocks the binding of pepstatin A. Screening of pepsin-like aspartic protease inhibitors against Pfm-PMX model suggests that the enzyme has higher affinity toward the compounds which inhibit β-secretase (BACE-I) and HIV-1 proteases (Data S2).

3 DISCUSSION

Plasmepsin X (PMX) has gained a lot of recent attention as one of the high priority antimalarial drug targets, due to its involvement in the invasion and egress processes of the malarial parasite. PMX-like enzymes are of great interest for antiparasitic drug development as these pepsin-like aspartic proteases are also essential for the life cycle of many apicomplexan parasites. We have expressed P. falciparum PMX zymogen (Pfpro-PMX) in HEK cells and produced stable and soluble protein for structural and biochemical studies. Auto-activation of Pfpro-PMX is due to multiple cleavage of the prosegment leading to formation of the active Pfm-PMX, similar to the sequential cleavage of the prosegment observed for vacuolar PM zymogens.22 Notably, the purified enzyme shows high thermal stability at acidic pH in the presence of inhibitor 49c, suggesting protonated active site residues facilitating stabilization of the enzyme-inhibitor complex, as observed for other pepsin-like aspartic proteases.

The Pfpro-PMX is much longer compared to its counterparts in other vacuolar plasmepsins,27 as well as in gastric and plant pepsin-like aspartic protease zymogens and exhibit very low sequence similarity with the enzymes belonging to the same family.20, 28 Pfpro-PMX has a unique UD in the prosegment. The Pfpro-PMX does not have any membrane-anchoring region, in contrast to such regions present in zymogens of vacuolar PMs (PMI-PMIV) and of nonvacuolar PMV.29 Although the mature Pfm-PMX is structurally similar to other pepsin-like aspartic proteases, the folding of the prosegment of Pfpro-PMX is unique. Inactivation of Pfpro-PMX is not only facilitated by the obstruction of the catalytic aspartates by R244, somewhat similar to the one observed for gastric and plant pepsin-like aspartic protease zymogens which utilize a lysine residue, but also by the projection of the twisted loop region of the prosegment into the active site. Such a mechanism of obstruction of the active site by a prosegment loop region has not been reported so far for any other structurally characterized pepsin-like aspartic protease zymogens. Surprisingly, the inactivation mechanism of Pfpro-PMX is vastly different from the mechanism employed by vacuolar PM zymogens.

Inactivation in vacuolar PM zymogens is achieved by spatial separation of the two domains of the mature protein by the prosegment, resulting in the separation of the catalytic aspartates,22, 30 thus, rendering the enzyme inactive. Recently, the “S”-shaped dimeric structures of vacuolar PM zymogens have been reported to be associated with their inactive state, while dissociation of dimer to monomer under acidic conditions has been shown to be the first step toward the trans-activation for forming mature enzymes.22 Analysis of the crystal structure of Pfpro-PMX shows the presence of a domain-swapped dimeric structure; however, its implication in inactivation of this enzyme needs further investigations. We suspect that the acidic conditions would cause protonation of the residues of the prosegment of Pfpro-PMX resulting in significant structural changes, thus, initiating the process of activation. Since, the plausible cleavage sites (CS-1 and CS-2) for activation of Pfpro-PMX are far away from the active site, similar to vacuolar PM zymogens, it is likely that the former might also adopt a similar trans-activation pathway as has been recently proposed for the latter.22 However, the in vivo activation process of Pfpro-PMX is ambiguous,24 hence, further studies are needed to provide more insights into the activation mechanism of this enzyme.

After cleavage of the prosegment, the N-terminal polypeptide region of the mature enzyme undergoes significant structural changes that lead to formation of the first β-strand of the active Pfm-PMX. Such conformational changes are also observed during the activation process of other pepsin-like aspartic proteases.22, 23 Other notable structural changes of Pfpro-PMX include closure of the flap and downward movement of loops N1 and N2. A major substitution in the substrate-binding pocket of Pfm-PMX involves F311 from the flap, which replaces the position of the highly conserved Y77 (pepsin numbering) of the pepsin-like proteases. That residue is believed to facilitate the catalytic mechanism by increasing the acidity of the N-terminal catalytic aspartate (D32 in pepsin).25 However, in Pfm-PMX the proton relay is still possible from W273 to D266 through a water molecule and S269, without the involvement of any residue from flap. Such mechanism is not common among pepsin-like aspartic proteases, although the existence of such a mechanism was postulated for HAP.31 Notably, strict conservation of F311 in Pfm-PMX and in related proteases points toward a possibility of a modified catalytic mechanism. Rotation of the carboxylate groups of the catalytic aspartates (D266 and D457) is observed in a simulated structure of Pfm-PMX-Apo and similar multiple conformational states have also been reported for PfPMV29 and the crystal structures of PfPMII.32 Comparison of the P3–P2′ cleavage sites in a majority of the Pfm-PMX substrates suggests that the P1 and P1′ are occupied by nonpolar residues, whereas P2′ position is mostly occupied by a negatively charged residue. Modifying the P2–P2′ positions to Ala leads to significant loss of cleavage efficiency of PfPMX.19 The residue at the P1 position is placed in the S1 hydrophobic pocket of the active site of Pfm-PMX, similarly to other pepsin-like aspartic proteases.28, 29 A previous report on PMX-like proteases showed the binding of a substrate in the active site of PfPMIX, PfPMX, and TgASP3 in an opposite orientation as compared to the inhibitor 49c, hence, resulted in assignment of the S1 pocket as S1′.18 P1 position of the substrate (HSF/IQ) in the Pfm-PMX active site in our study follows the same orientation as that depicted earlier for 49c in the Pfm-PMX and TgASP3 active sites. Also, P1′ Ile of our substrate occupies the same position as L103p of the twisted loop in the zymogen, supporting further the mode of substrate-binding presented here. In addition, the two catalytic aspartate carboxylate groups of Pfm-PMX are at a favorable distance from the scissile peptide bond (between F and I) to facilitate catalysis. Further detailed structural, biochemical, and quantum mechanical (QM)/molecular mechanics (MM) studies would provide more evidence toward the catalytic mechanism of Pfm-PMX.

Despite setting up a variety of crystallization screens, the Pfm-PMX-49c complex could not be crystallized. However, the details of the interactions involved in binding of this potent inhibitor to the Pfm-PMX active site were obtained from our MD simulation studies. Although the orientation of 49c in the Pfm-PMX active site is similar to that reported previously,18 there are several striking differences observed in our complexed structure and those interactions might be essential for stronger binding of this inhibitor. Docking-based screening highlighted that the inhibitors of BACE-I bind more tightly to the Pfm-PMX active site. Our structural analysis also provides rationale for the earlier observation that Pfm-PMX is not inhibited by pepstatin A, a potent inhibitor of pepsin-like aspartic proteases.12 Inability of pepstatin A to inhibit Pfm-PMX is primarily due to the presence of Y462, which prevents binding of the inhibitor in the S4 pocket of the active site. Similar blocking of the S4 pocket by F370 in PfPMV has been shown to be the primary reason for its lack of binding with pepstatin A.29

In conclusion, the experimental structure of Pfpro-PMX and computational model of Pfm-PMX (both in the apo- and in complex with substrate and inhibitors) provide comprehensive insights into the folding of the prosegment and the architecture of the active site of this enzyme. These findings can be extrapolated to other PMX-like proteases of apicomplexan parasites. The folding of the prosegment, and thus, the inactivation mechanism of Pfpro-PMX, is novel and, based on sequence and structural similarities, a similar mode of inactivation is anticipated to be present for other PMX-like proteases. As the binding pocket residues are highly conserved among the PMX-like aspartic proteases, the observed mode of binding of 49c and top-hit inhibitors from our computational study in Pfm-PMX should aid in screening more drug analogs to identify lead candidates for the development of more potent inhibitors of these classes of enzymes. Therefore, the structural features of the Pfm-PMX highlighted in this study should facilitate development of the antiparasitic drugs.

4 MATERIALS AND METHODS

4.1 Expression and purification of recombinant Pfpro-PMX (R28p-N573) (Construct 1) in HEK cells

The synthetic gene encoding the Pfpro-PMX (R28p–N573) of P. falciparum plasmepsin X (XP_001349441) (Figure 5a) was engineered for expression in a mammalian host (Human Embryonic Kidney cells, HEK cells) by GeneArt (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) and cloned into a variant of pTT5 with the mouse Ig secretion signal peptide on the N terminus and a TEV-cleavable 8x Histidine tag on the C terminus. The recombinant protein was expressed in Expi 293 GnTI- (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) at 37°C, using Expi293 expression media (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). After 5 days of culture, the medium was clarified by centrifugation, filtered, and applied to 2 × 5 ml HisTrap Ni Excel columns equilibrated with Buffer A (25 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP, 50 mM Arginine, 0.25% Glycerol). After the protein was loaded, the column was washed with 50 ml of 2% Buffer B (25 mM Tris HCl, pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP, 500 mM imidazole), followed by 50 ml of 4% Buffer B. The protein was eluted with a linear gradient of 4–60% Buffer B. Fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE using 4–12% gradient gels in the MOPS buffer. Fractions containing the Pfpro-PMX were pooled and dialyzed overnight at room temperature into Buffer A containing 10 mg/ml TEV and 170,000 U of EndoH. The extent of tag removal and deglycosylation was assessed by SDS-PAGE. The untagged and deglycosylated protein was applied to 1 × 5 ml HiTrap Ni Chelating Column equilibrated with Buffer A. The column was washed 50 ml of Buffer A and the protein was eluted with a linear gradient of 0–60% Buffer B. Fractions containing the untagged and deglycosylated Pfpro-PMX were observed in the flow thru and fraction 1 of the gradient elution. Fractions were pooled and concentrated to ~12 mg/ml for size exclusion chromatography (SEC). The concentrated protein was applied to a 1 × 120 ml Superdex 200 column in the SEC buffer (25 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP, 1% glycerol). Fractions containing the protein of interest were pooled and concentrated to 11.4 mg/ml for crystallization and a second pool of protein, concentrated to 13.3 mg/ml, was used for assays.

4.2 Study of 49c binding by nanoDSF

A label-free nanoscale differential scanning fluorimetry (nanoDSF) method was used to assess the effect of compound 49c on PfPMX stability. PfPMX was diluted to 0.5 mg/ml (7.9 μM) in the MES buffer in varying pH conditions (25 mM Tris/HCl, 25 mM MES pH 5.5, 6.5, 7.5, 8.5 and 9.5). Thermal stability of PfPMX was characterized at each pH condition with and without 49c at 160 μM. All samples were tested at the final 0.16% concentration of DMSO. Samples were loaded in standard capillaries (PR-C002, NanoTemper Technologies) with a final volume of 10 μl. PfPMX intrinsic fluorescence (aromatic residues fluorescence) was measured over a linear thermal gradient 20–95°C at 1°C min−1 with an excitation power set to 40%. Fluorescent measurements were made at excitation 280 nm (UV-LED) and at emission wavelengths of 330 and 350 nm using Prometheus NT.48 (NanoTemper Technologies). Data from duplicate measurements of each sample were processed using PR.ThermControl Software (NanoTemper Technologies).

4.3 Crystallization, diffraction data collection, and structure solution of Pfpro-PMX

Purified Pfpro-PMX (SSGCID batch ID PlfaA.17789.b.HE11.PD28363) at 11.4 mg/ml was crystallized via vapor diffusion using a condition derived from JCSG+ screen (RigakuReagents), condition A7 (100 mM TrisHCl/NaOH pH 9.4, 18% [w/V] PEG 8000) with 0.4 μl protein + 0.4 μl reservoir as sitting drops in 96-well XJR trays (Rigaku Reagents) at 14°C. Crystals were cryoprotected with 20% ethylene glycol as cryoprotectant added to the reservoir solution. Diffraction data were collected at the Life Sciences Collaborative Access Team beamline 21-ID-F at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory using a Rayonix MX-300 detector. The diffraction data were reduced with XDS/XSCALE33 to 2.1 Å resolution. The intensities were converted to structure factors with the program modules F2MTZ and CAD of CCP4.34

The structure was solved via Molecular Replacement with MR-ROSETTA35 using PDB entry 3PSG as the search model. The structure was further modeled in iterative cycles of real-space refinement in Coot,36, 37 and through reciprocal space refinement in phenix.refine.38 The structure was subsequently refined for 10 cycles using REFMAC5.39 The resulting electron density map visualized in Coot indicated better features of the missing residues and ligands of the Pfpro-PMX model. Subsequently, manual model building was performed by visual inspection and refinement using REFMAC5. The ligands, solvent molecules, and ions were progressively added at peaks of electron density higher than 3σ in sigma-A weighted Fo–Fc electron density maps while monitoring the decrease of Rfree and improvement of the overall stereochemistry. The polypeptide region with residues K69p–N70p and E132p–K224p in the prosegment and the C-terminal linker region could not be modeled due to the lack of features in the electron density. With the exception of a few residues (H308–S315) in the flap, (E343–D352) in N2 loop and the last residue N573, the complete mature enzyme portion of the Pfpro-PMX structure could be modeled and refined. The side chains of the residues with weak or missing electron density have not been added in the structure. The adjacent disulfide bond (447–448) is modeled as cis peptide bond conformation.40 The data collection and refinement statistics are presented in Table 1. Quality assessment tools built into Coot, phenix, and MolProbity41 were used to assess the quality of the structure during refinement.

The structure was deposited in the PDB with code 7RY7. Diffraction images were made available to the Integrated Resource for Reproducibility in Macromolecular Crystallography (www.proteindiffraction.org).42

4.4 Modeling of mature Pfm-PMX

A model of Pfm-PMX (I235–K572) was generated by comparing the crystal structure of Pfpro-PMX and the model obtained from SwissModel (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/). The quality of the model was assessed by the Ramachandran plot and visual inspection of the active site. Furthermore, the stability of the Pfm-PMX model was monitored by molecular dynamics (MD) simulation as discussed in the next section.

4.5 Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of Pfm-PMX as Apo and its complexes

All the molecular dynamics (MD) simulations in this study were performed by GROMACS 2019.1 with “Amber99SB” force field.43 The force field parameters for the ligands were generated using Antechamber. The “xleap” module of AmberTools was used to generate topologies for Pfm-PMX Apo as well as complexes taking care of the disulfide bonds. The protein molecules (as apo or complexed) were placed at the center of the box with a distance of 20 Å from the wall surrounded by TIP3P water molecules with periodic boundary conditions. The complexes were neutralized by adding the appropriate number of required counter ions. The ParmED (https://parmed.github.io/ParmEd/html/parmed.html) tool was used to convert the topology files obtained from xleap module of AmberTools for the use of those by Gromacs. Energy minimizations were performed for 50,000 steps. The energy minimized systems were further equilibrated using canonical ensemble (NVT) followed by isothermal-isobaric ensemble (NPT). In the NVT equilibration, systems were heated to 300 K using V-rescale, a modified Berendsen thermostat for 1 ns. In NPT, all these heated systems were equilibrated using the Parrinello Rahman barostat for 1 ns to maintain a constant pressure of 1 bar. The unrestrained production MD simulations were performed for 100 ns for all structures. The covalent bonds involving H-atoms were constrained using the “LINCS” algorithm and the long-range electrostatic interactions with particle mesh Ewald (PME) method. The time step for integration was set to 2 fs during the MD simulation.

MD simulation trajectories were further analyzed by using the inbuilt tools in GROMACS 2019.1 and visual molecular dynamics (VMD).44 The images were generated using the Discovery studio visualizer (https://www.3ds.com/products-services/biovia/) and PyMol (https://pymol.org/2/). All simulations were performed on the Spacetime High-Performance Computing (HPC) resource at IIT Bombay.

4.6 Sequence alignment

All the sequence alignments have been performed using PROMALS3D multiple sequence and structure alignment server (http://prodata.swmed.edu/promals3d/promals3d.php) and T-COFFEE server (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/tcoffee/). These alignments were curated manually and the figures were prepared using ESPRIPT server (https://espript.ibcp.fr/ESPript/ESPript/).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Pooja Kesari, Nikhil Pahelkar, Ishan Rathore, and Vandana Mishra thank the Indian Institute of Technology Bombay (IIT Bombay) for financial support; Anuradha Deshmukh thanks University Grant Commission (UGC), India and Abhishek B. Suryawanshi thanks Department of Biotechnology, Ministry of Science and Technology, India for their fellowship. The work was supported by the Ramalingaswami Re-entry Fellowship (DBT), a research seed grant from IRCC, IIT Bombay to Prasenjit Bhaumik. We would like to thank Spacetime High-Performance Computing (HPC) resource in IIT Bombay, Mumbai, India for generous computing time. The “Protein Crystallography Facility” at IIT Bombay is also acknowledged. Funding to Rickey Y. Yada from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada (grant number RGPIN 04598) is also gratefully acknowledged. The study was supported in part by the funding to Alla Gustchina and Alexander Wlodawer from the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. Use of the LS-CAT Sector 21 was supported by the Michigan Economic Development Corporation and the Michigan Technology Tri-Corridor (Grant 085P1000817). This project has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under Contract No.: HHSN272201700059C.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Pooja Kesari: Conceptualization (equal); data curation (equal); formal analysis (equal); investigation (equal); methodology (equal); validation (equal); visualization (equal); writing – original draft (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Anuradha Deshmukh: Conceptualization (equal); data curation (equal); formal analysis (equal); investigation (equal); methodology (equal); validation (equal); visualization (equal); writing – original draft (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Nikhil Pahelkar: Investigation (supporting); methodology (supporting); writing – review and editing (supporting). Abhishek B. Suryawanshi: Investigation (supporting); methodology (supporting); writing – review and editing (supporting). Ishan Rathore: Investigation (supporting); methodology (supporting); writing – review and editing (supporting). Vandana Mishra: Investigation (supporting); methodology (supporting); writing – review and editing (supporting). John H. Dupuis: Writing – review and editing (supporting). Huogen Xiao: Writing – review and editing (supporting). Alla Gustchina: Writing – review and editing (supporting). Jan Abendroth: Data curation (equal); formal analysis (equal); investigation (equal); methodology (equal); validation (equal); visualization (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Mehdi Labaied: Data curation (equal); formal analysis (equal); investigation (equal); methodology (equal); validation (equal); visualization (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Rickey Y. Yada: Writing – review and editing (supporting). Alexander Wlodawer: Writing – review and editing (supporting). Thomas E. Edwards: Data curation (equal); formal analysis (equal); investigation (equal); methodology (equal); validation (equal); visualization (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Donald D. Lorimer: Funding acquisition (equal); resources (equal); supervision (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). PRASENJIT BHAUMIK: Conceptualization (equal); data curation (equal); formal analysis (equal); funding acquisition (equal); resources (equal); supervision (equal); validation (equal); visualization (equal); writing – original draft (equal); writing – review and editing (equal).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Authors declare no competing interests.