Multicentre Randomized Controlled Trial of a Nurse-Led Sexual Rehabilitation Intervention to Rebuild Sexuality and Intimacy After Treatment for Gynecological Cancer

Funding: The study is fully funded by Health and Medical Research Fund (HMRF) Research Fellowship Scheme from Food and Health Bureau, the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (#03170057).

ABSTRACT

Objective

To evaluate the effectiveness of a sexual rehabilitation program, SEXHAB, in improving sexual functioning, reducing sexual distress, and enhancing marital satisfaction for women after gynecological cancer treatment.

Methods

This is a randomized controlled trial that included 150 women newly diagnosed with gynecological cancer from three public hospitals in Hong Kong. Participants were randomly assigned to the intervention group (n = 78) to receive the SEXHAB or to an attention control group (n = 72) to receive attention. The SEXHAB comprises four individual- or couple-based sessions with three major components: information provision, cognitive-behavioral therapy and counseling using motivational interviewing skills. The outcomes were measured at baseline (T0), upon completion of the program (T1) and 12-month post-treatment (T2). Semi-structured interviews were also conducted with the SEXHAB group participants to explore their experiences with and opinions toward the program.

Results

At both follow-ups, there were no statistically significant differences between groups in improving sexual functioning, sexual distress and marital satisfaction. Nevertheless, participants in the SEXHAB group reported their partners having significantly greater sexual interest at T1 (76% vs. 52%, rate ratio: 1.46, 95% CI: 1.07 to 1.99, p = 0.024) and T2 (74% vs. 48%, rate ratio: 1.55, 95% CI: 1.11 to 2.10, p = 0.014). From the qualitative interviews, the interviewees who resumed sexual activity reported positive experiences in rebuilding sexuality and intimacy.

Conclusions

Despite the quantitative results are negative, the qualitative findings suggest potential benefits of the SEXHAB for women resuming sexual activities after treatment for gynecological cancer. Further studies with longer intervention period and follow-ups are needed to confirm the intervention effects.

1 Introduction

As the gynecological cancer (GC) survival rate increases with improved treatments, more attention has been paid to the quality of life of women treated for GC, where issues of intimacy and sexuality are regarded as essential components [1]. Sexual dysfunction is a common problem experienced by women after treatment for GC, affecting up to 50% of women treated for GC [1]. Regardless of the cancer site, more intensive treatments (such as chemotherapy and radiation therapy) were associated with severe sexual side effects [2]. Examples of common side effects associated with GC treatments include vaginal dryness, dyspareunia and lower sexual desire [2, 3]. Very often, women refrain from sexual activity out of the fear of painful sexual intercourse and uncertainty in illness. Research has shown that sexual concerns, if not addressed, can lead to distress and disruptions to intimacy and relationship quality [3-5]. As such, rebuilding sexuality after treatment is pivotal for these women to maintain intimate relationships with their partners.

Sexual rehabilitation intervention is characterized by comprehensive assessment and appropriate interventions from a holistic perspective [6]. Nurse-led sexual rehabilitation intervention has shown promising results, as evidenced by Bakker et al.’s study on sexual recovery and vaginal dilatation after radiation therapy for cervical cancer. The findings indicated significant improvement in sexual functioning from 1 to 6- and 12-month post-treatment [7]. However, the study was a pilot scale, focusing on cervical cancer only. Given the lack of evidence on sexual rehabilitation for women treated for GC and a strong desire for psychosexual support and practical advice concerning coping strategies for sexual problems expressed by this cohort [8, 9], we conducted a randomized controlled trial (RCT) to test the effectiveness of a nurse-led sexual rehabilitation program, SEXHAB, compared with standard care in improving sexual functioning, reducing sexual distress, and enhancing marital satisfaction after treatment for GC.

The SEXHAB aims to support women treated for GC and their partners to resume a satisfying intimate relationship or adapt to permanent sexual dysfunction in the forms of sexual expression. Its development was guided by the concept of sexual health comprising three interrelated components—sexual self-concept (including body image, sexual self-schema, and sexual esteem), sexual relationships (including communication and intimacy), and sexual functioning (sexual response cycle), as stated in the Neotheoretical Framework of Sexuality [10]; the Extended Permission-giving, Limited Information, Specific Suggestions, and Intensive Therapy (Ex-PLISSIT) model [11, 12]; the empowerment model, which features knowledge, behavioral skills and self-responsibility [13]; and evidence-based nursing interventions for sexuality [7, 12]. We hypothesized that the intervention, in comparison to standard care, would improve the primary outcome of sexual functioning and the secondary outcomes of sexual distress and marital satisfaction.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design

This study was a two-arm, assessor-blinded, multi-centre, parallel mixed-methods, RCT. This study was registered on 6 September 2019 with the ISRCTN Registry (registration number: ISRCTN44439658).

2.2 Participants

Between July 2019 and July 2021, women diagnosed with primary GC (uterine, ovarian or cervical cancer) in the past three months but not in the terminal stage of the disease, having a regular sexual partner and aged over 18 were recruited by a research nurse in the gynecological oncology clinics or wards. Women with known pre-existing psychotic illness were excluded due to the potential adverse sexual effects of commonly prescribed medication [14], which could introduce bias in the assessment of the outcomes. Consented participants completed a self-administered questionnaire, and their clinical information was extracted from medical record by the research nurse.

2.3 Randomization and Blinding

Participants were randomly assigned to the intervention or attention control group using computer-generated random codes by a statistician with stratified block randomization for the three hospitals, with a block size of 10, except the last block, and an allocation ratio of 1:1. Outcome assessor and statistician who analyzed the data were blinded to the group assignment.

2.4 Intervention

Details of the SEXHAB have been reported in our protocol [15]. It comprises four individual- or couple-based sessions delivered by a trained research nurse on four occasions: before the commencement of cancer treatment, 1 month after the completion of treatment, 2-month post-treatment and 6-month post-treatment. Each session lasted 45–60 min. The partners of the participants were invited to join voluntarily. The intervention included three major components: information provision, cognitive-behavioral therapy and counseling using motivational interviewing skills. Information regarding the diagnosis, treatment and possible consequences for sexuality and intimacy was provided. Potential barriers to resuming sexual activity after treatment and the concern of resuming a sex life were discussed. The participants' experiences of resuming sexual activity or non-sexual intimate acts were explored and tailored practical advice was given [7, 11]. Evidence-based practices for promoting sexuality, such as behavioral attempts (e.g., candlelight; massage; having a bath together; erotic clothes, pictures or videos), and practical strategies to resolve sexual problems, including the use of a vaginal lubricant, new sexual positions and oral-genital sex, were also discussed. Activities for promoting a positive body image, such as good hygiene, perfume, wigs and make-up, were recommended [12]. Couples' mutual support and joint coping methods, improved communication using skills such as problem solving and feeling expression and alternative ways to express support and affection for each other were encouraged [7, 11].

To rule out the possibility that the observed effects are caused by the specific attention given [16], participants in the control group received attention from the research nurse on the aforementioned four occasions during the intervention period. The research nurse did not provide any type of intervention and only met the participants to invite them to join the study and collect baseline data after recruitment. At 1-, 2- and 6-month post-treatment, the research nurse called them by phone to deliver general greetings.

2.5 Outcomes

A study-specific socio-demographic datasheet was used to collect demographic and clinical details at baseline (T0). In addition, sexual functioning, sexual distress and marital satisfaction were assessed at T0, immediately after the completion of the SEXHAB (T1) and 12-month post-treatment (T2) using the validated questionnaires described below.

2.5.1 Primary Outcome

The Chinese version of the 27-item Sexual Function-Vaginal Changes Questionnaire (SVQ) [17] was used to assess sexual functioning. This scale consists of 20 core items measuring female sexual functioning and seven items assessing changes in levels of sexual and vaginal problems as compared to pre-diagnosis. The items are clustered into five subscales: intimacy (2 items), global sexual satisfaction (2 items), sexual interest (1 item), vaginal changes (4 items) and sexual function (3 items). The Chinese version of the SVQ has been validated among Hong Kong women with GC with good internal consistency, item-to-scale correlations and test-retest reliability [17].

2.5.2 Secondary Outcomes

The Chinese version of the 13-item Female Sexual Distress Scale-Revised (FSDS-R) was used to examine sexual distress. Each item is rated on a scale of 0–4, with a higher score indicating a higher level of sexual distress [18]. The scale has demonstrated good reliability and validity among women treated for cervical cancer [7]. We have translated the Chinese version using the Brislin model of translation and guidelines for the cross-cultural adaptation of scales, and a panel of six health care professionals assessed its semantic equivalence and content validity, resulting in a content validity index ranging from 0.83 to 1.0.

The Chinese version of the 15-item ENRICH Marital Satisfaction Scale (EMS) was used to evaluate relationship satisfaction with partner [19]. The 15 items are clustered into two subscales: idealistic distortion (5 items) and marital satisfaction (10 items). The 10-item marital satisfaction subscale was used in this study. Each item is rated on a scale of 1–5, with higher scores indicating better relationship. The Chinese version of the EMS has been validated among Chinese couples with discriminant validity and good internal consistency [19].

Semi-structured interviews with SEXHAB participants were conducted by another research nurse immediately after the program's last session up to the point of data saturation (no new themes emerged from successive interviews) to collect their views of intervention. All interviews were audio-recorded and guided by open-ended, probing questions such as ‘What is your general impression of the program?’ and ‘Tell me about your experience of the sexual rehabilitation program’.

2.6 Data Analysis

A previous study that examined the effect of a nurse-led sexual rehabilitation intervention among the target population and yielded a significant improvement in the primary outcome of sexual functioning. In that study, the effect sizes of the intervention at 6 and 12 months were preliminarily estimated to be 0.95 and 1.63, respectively [7]. Without a consented or conventionally adopted clinical meaningful difference or change for our primary outcome of sexual functioning, our research team made a consensus to define a clinically meaningful change as a 0.5 standard deviation (SD) improvement in the primary outcome of sexual functioning a priori. Such an effect is conventionally considered as a medium effect size [20]. We estimated that a sample size of n = 64 per group would give the study 80% power at a 5% level of significance (2-sided) to detect an effect size of at least 0.5 for the primary outcome of sexual functioning at post-intervention. Further allowing for an attrition rate of 25%, we originally determined a sample size of 86 participants per study arm. However, due to COVID-19 pandemic leading to delayed study progress and a lower attrition rate than expected, we terminated subject recruitment when 150 participants were recruited.

Appropriate descriptive statistics were used to summarize socio-demographic and clinical characteristics between the intervention and attention control groups. The FSDS-R total score was square root transformed before being entered into inferential analysis. A generalized estimating equations (GEE) model was used to compare the differential changes of each outcome score at T1 and T2 with respect to T0 between the intervention and control groups with adjustment for the randomization stratification factor (hospital). Since there were considerable proportion (> 20%) of participants with missing values in one or more outcome scores at T0, T1 and/or T2, complete case analysis may lead to biased results if the data were not missing completely at random. In fact, there were considerable differences in some clinical characteristics between those who completed the primary outcome assessments (n = 131) and those who missed at least one follow-up assessment (n = 19) (Table S1), which indicated the missingness might be associated with such characteristics and hence missing completely at random might not be plausible. We therefore handled the missing data by using multiple imputation which holds under a less restrictive assumption on the missingness of the data (namely, missing at random). We used all available demographic and clinical characteristics listed in Table S2 and outcome data to perform multiple imputations by using fully conditional specification with the predictive mean matching method [21] impute missing outcome data at T0, T1 and T2 resulting in 10 imputed datasets. The Rubin's method [21] was then used to pool the GEE analysis results for each outcome across the imputed datasets. Additionally, chi-squared or Fisher's exact tests were used to compare the differences in individual items of SVQ between the two study groups at post-intervention T1 and T2 with Bonferroni correction. All the statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS 26 (IBM Crop. Armonk, NY). All the statistical tests involved were 2-sided with level of significance set at 0.05.

Audiotapes of the interviews were transcribed verbatim and then checked for any discrepancies. The transcripts were content analyzed following transcription to identify persistent words and code themes concerning sexuality and intimacy within the qualitative data. The significant categories and themes were then translated into English [22]. To strengthen the credibility of the qualitative findings, an independent researcher conducted interviews using an interview guide. Additionally, two researchers independently analyzed the data and reached consensus on the emergent subthemes and themes [23].

2.7 Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committees of three participating hospitals in Hong Kong (reference numbers: 2018.112, KC/KE-18-0164/ER-4 and HKECREC-2018-0100). All participants received written and verbal information about the study and signed written consent.

3 Results

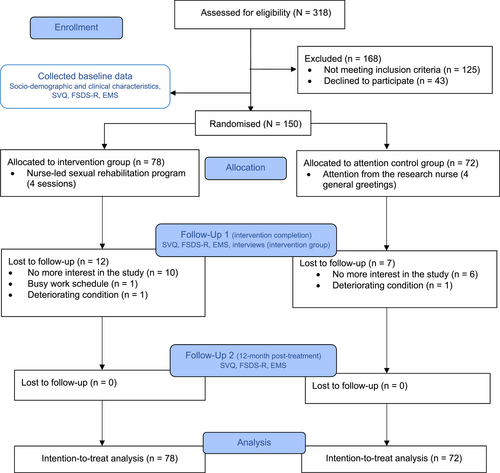

A total of 150 consenting participants were recruited and randomized into the intervention (n = 78) and attention control groups (n = 72). Nineteen participants dropped out from the study, with 12 in the intervention group and 7 in the control group, due to loss of contact, busy work schedule, or deteriorating condition. There were considerable differences in some baseline characteristics between those who dropped out from the study and those who did not (Table S1). No harmful effects were reported from receiving the intervention. All the randomized participants were included in the quantitative analysis. The CONSORT diagram of the study is shown in Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram. EMS, ENRICH Marital Satisfaction Scale; FSDS-R, Female Sexual Distress Scale-Revised; SVQ, Sexual Function-Vaginal Changes Questionnaire.

The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants are summarized in Table S2. Participants in the intervention group were, on average, younger than those in the control group, while educational level, household income and types of treatment modalities received were generally comparable between groups. However, relatively more participants in the control group had 2 or more children, diagnosed with corpus uteri cancer, and were at stage III of cancer when compared with their counterparts in the intervention group.

3.1 Effects of Intervention on Sexual Functioning, Sexual Distress and Marital Satisfaction

The descriptive statistics of the sexual functioning, sexual distress and marital satisfaction outcomes are presented in Tables S3 and S4. A total of 61 participants reported having sexual relations in one or more of the outcome assessments conducted at T0, T1 and T2. As some of the items of the SVQ are only relevant for those who have sexual relations, the vaginal changes and sexual function subscales of the SVQ involved only a subgroup of the participants. There were no noticeably greater improvements found in the intervention group when compared with the control group except that participants in the intervention group were more likely to perceive greater sexual interest from their partners after intervention at T1 (76% vs. 52%, rate ratio: 1.46, 95% CI: 1.07 to 1.99, p = 0.024) and T2 (74% vs. 48%, rate ratio: 1.55, 95% CI: 1.11 to 2.10, p = 0.014) (Table S4). The GEE analyses revealed no statistically significant differences in changes of all SVQ subscale scores, including intimacy, global sexual satisfaction, sexual interest, vaginal changes and sexual function as well as the FSDS-R and EMS scores at T1 and T2 with respect to T0 (all group-by-time interactions were not statistically significant, Table S5).

3.2 Participants' Views of the Intervention

Of the 66 intervention completers, 42 participated in the semi-structured interviews. Content analysis revealed a major theme − positive experiences in rebuilding sexuality and intimacy. The subthemes and codes are summarized in Table S6.

Of the 42 interviewees, most of them acknowledged that the nurse intervener played a significant role in providing sexuality care. However, only less than half reported having resumed sexual activity and the most common sexual difficulty was vaginal dryness, which tended to cause pain and discomfort during sexual intercourse. The participants reported relief from vaginal dryness by adopting practical strategies to resolve sexual problems recommended by the nurse intervener. Some interviewees reported experiencing sexual distress due to the fear of sexual pain, fear of infection and altered body image. They shared their fears and worries with the nurse intervener, who helped clear up some misconceptions and comforted them. Subsequently, their distress was relieved. Some women were grateful for the new insights provided by the nurse intervener regarding building intimacy with their partners. They highlighted some successful experiences in applying the strategies for effective communication and exploring alternative ways to express affection.

4 Discussion

This study is the first to evaluate the effects of a theory-driven nurse-led sexual rehabilitation intervention that incorporates the Neotheoretical Framework of Sexuality, Ex-PLISSIT model, and empowerment model, on sexual functioning.

Regarding the outcome of sexual functioning, both groups demonstrated small but significant within-group improvements in intimacy, global sexual satisfaction and sexual interest (Table S3) at both timepoints. However, there were no statistically between-group significant differences in the SVQ subscale scores at both timepoints. Despite the non-significant quantitative results, the qualitative findings suggest some improvement in vaginal problems among the sexually active women with reported relief from vaginal dryness by adopting practical strategies recommended by the nurse interveners. In fact, nearly half of this cohort reported being sexually inactive in the previous month at 12-month post-treatment, which might account for the non-significant results. A recent RCT of a nurse-led sexual rehabilitation intervention grounded in positive psychology among a sample of Chinese women treated for cervical cancer observed that most of the participants had resumed sexual activities only after a very long period postoperatively, ranged from 1 to more than 3 years post-treatment [24]. This suggests that the beneficial effects on sexual functioning of our sexual rehabilitation intervention may take a longer time to be apparent. Further studies should extend the length of the intervention and evaluate its effects on sexual functioning. Importantly, the reported timing of sexual activity resumption is much longer than the clinical recommendation of around 3 months after treatment. This discrepancy suggests the presence of potential barriers to sexual rehabilitation that warrant further investigation.

Nevertheless, the women in the SEXHAB group perceived their partners having greater sexual interest than did the control participants upon completion of the intervention and at 12-month post-treatment. This finding concurs with the finding of our previous study that evaluated the effects of a psychoeducational intervention on the same target population at 12-week post-operation for GC [25]. Notably, in the present study, the involvement of partners in the intervention was encouraged and only 30 out of 66 intervention participants had their partners attending at least one session. As partners play a significant role in the abilities of GC patients to adjust to sexual changes, future research should recruit the partners of all participants to receive the intervention and explore the effects of this program on their sexual health [26].

We observed a small but significant within-group increase in sexual distress at both timepoints (Table S3). However, in contrast to the findings of an earlier study of a psychoeducation intervention for GC patients [27], no statistically significant between-group difference was observed in our study in terms of changes in the level of sexual distress. However, sexual distress was found to be extremely low in both groups of participants at all time points, indicating that they did not worry about sexual relations and functioning. Such a low level of sexual distress and high prevalence of sexual inactivity might be attributed to their cultural background that Chinese culture emphases refraining from sexual activity during recovery from disease [28]. On the other hand, the qualitative findings revealed the potential benefits of the intervention for women with high level of sexual distress, indicating reduction in sexual distress and improvement in intimate relationships with their partners. Considering that nearly half of the women in this study may resume sexual activities later than 12-month post-treatment, further studies should examine the changes in sexual distress over a longer period of time.

No statistically significant between-group difference in marital satisfaction was observed in this study. The EMS scores of both groups ranged from 33.7 to 36.4 within a possible range of 10–50. According to the scoring scale of the instrument [29], this range is classified as somewhat satisfactory to satisfactory in most aspects. Our inclusion criteria of having a regular sexual partner might have introduced recruitment bias, with only women with satisfying sexual relations being recruited. Sex contributes 15%–20% to a marriage happiness [30]; thus, having an active sex life with one's spouse might indicate satisfactory marital relationships at baseline.

5 Study Limitations

This study has several limitations of note. First, the participants were recruited from three regional hospitals in Hong Kong, which may limit the generalisability of our findings to other settings. Second, early-stage cancer patients were overrepresented in this sample. Third, the partners of only a minority of participants joined the intervention sessions with them, which is likely to have introduced inconsistency in the intervention format. However, subgroup analysis revealed no significant differences in the changes of outcomes between participants whose partners had at least attended one session and those who had not. Fourth, as some of the participants did not have sexual relations during one or more data collection periods and hence they did not respond to some of the sexual functioning assessment items, which reduced the effective statistical power of the study for some outcomes. Finally, as only a minority of the interviewees in the qualitative study reported having resumed sexual activity at 6-month post-treatment, we were not able to capture the positive sexuality- and intimacy-rebuilding experiences of those who resumed sexual activity between 6- and 12-month post-treatment.

6 Clinical Implications

Despite there is no statistically significant improvement in the quantitative outcomes, qualitative findings suggested potential benefits to women who resumed sexual activity after treatment completion. In this study, only around half of this cohort resumed sexual activity at 12-month post-treatment implying that women may perceive lower priorities for addressing sexual and intimacy issues during early stages of survivorship. However, it is possible that the priority placed on these issues may increase as women gradually resume sexual activities at a later stage. As such, the timing of delivering sexual health interventions should be responsive to their evolving needs.

7 Conclusion

Admittedly, the SEXHAB is labor intensive, but supporting GC survivors and their partners to adapt to the changes in sexuality resulting from the disease and related treatments and rebuild sexuality and intimacy after treatment is challenging. Although the quantitative results are negative, given that the study is a high-quality study structured on an important, under-addressed issue, the study findings still warrant dissemination. Future research needs to consider prolonging the duration of SEXHAB and evaluate its longer-term effects after treatment.

Acknowledgements

The authors have nothing to report.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.