Randomized controlled trial of an individual blended cognitive behavioral therapy to reduce psychological distress among distressed colorectal cancer survivors: The COloRectal canceR distrEss reduCTion trial

Abstract

Objective

Colorectal cancer survivors (CRCS) often experience high levels of distress. The objective of this randomized controlled trial was to evaluate the effect of blended cognitive behavior therapy (bCBT) on distress severity among distressed CRCS.

Methods

CRCS (targeted N = 160) with high distress (Distress Thermometer ≥5) between 6 months and 5 years post cancer treatment were randomly allocated (1:1 ratio) to receive bCBT, (14 weeks including five face-to-face, and three telephone sessions and access to interactive website), or care as usual (CAU). Participants completed questionnaires at baseline (T0), four (T1) and 7 months later (T2). Intervention participants completed bCBT between T0 and T1. The primary outcome analyzed in the intention-to-treat population was distress severity (Brief Symptom Inventory; BSI-18) immediately post-intervention (T1).

Results

84 participants were randomized to bCBT (n = 41) or CAU (n = 43). In intention-to-treat analysis, the intervention significantly reduced distress immediately post-intervention (−3.86 points, 95% CI −7.00 to −0.73) and at 7 months post-randomization (−3.88 points, 95% CI −6.95 to −0.80) for intervention compared to CAU. Among secondary outcomes, at both time points, depression symptoms, anxiety symptoms, cancer worry, and cancer-specific distress were significantly lower in the intervention arm. Self-efficacy scores were significantly higher. Overall treatment satisfaction was high (7.4/10, N = 36) and 94% of participants would recommend the intervention to other colorectal cancer patients.

Conclusions

The blended COloRectal canceR distrEss reduCTion intervention seems an efficacious psychological intervention to reduce distress severity in distressed CRCS. Yet uncertainty remains about effectiveness because fewer participants than targeted were included in this trial.

Trial Registration

Netherlands Trial Register NTR6025.

1 BACKGROUND

Patient-centered care seeks to integrate understanding of the patients' emotional needs and life issues in addition to medical treatment.1 The diagnosis of colorectal cancer (CRC) and medical treatment together with persistent treatment-related side effects may negatively affect a patients' quality of life and lead to psychological distress. Distress is defined by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network as a “multifactorial unpleasant emotional experience of a psychological, social and/or spiritual nature that may interfere with the ability to cope effectively with cancer, its physical symptoms and treatment.” About one third of colorectal cancer survivors (CRCS) experience high levels of distress up to 5 years after medical treatment2, 3 including distress due to physical consequences,4, 5 anxiety,6, 7 fear of cancer recurrence8 and depressive mood.6, 7, 9

Evidence-based psychological interventions focusing on reducing severe distress after treatment in CRCS are scarce. A small trial (N = 59) has evaluated progressive muscle relaxation training 10-weeks after colorectal cancer patients received stoma surgery, which reduced state anxiety and improved quality of life.10 A feasibility trial (N = 40) of a 12-session emotional expression group intervention showed support for reducing distress at 4 months post-randomization.11 Thus, there are currently no robust trials that have evaluated the effects of psychological support interventions in a diverse group of colorectal cancer patients with long-term follow-up.

Psychological intervention content can ideally be tailored to individual patients and take advantage of new healthcare methods including eHealth. Guided eHealth cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBTs) have shown to be equally effective as face-to-face treatments for diverse psychiatric and somatic patient populations.12, 13 Combining face-to-face contact with online activities (blended therapy) reduces therapist workload and traveling for patients.14 Furthermore, blended therapy leads to better outcomes and reduced patient dropout compared to self-guided internet interventions.15 The COloRectal canceR distrEss reduCTion (CORRECT) intervention was designed to meet the need for a psychological intervention for reducing distress in CRCS who experience significant levels of distress.16 CORRECT was delivered as blended cognitive behavior therapy (bCBT) for 4 months, combining face-to-face sessions and telephone consultations with a cognitive-behavior therapist, with an interactive self-management website. The aim of the CORRECT trial was to evaluate the effect of bCBT compared to care as usual (CAU) in distressed CRCS who were between 6 months and 5-year post-medical treatment on distress (primary) and other mental health outcomes including depression symptoms, anxiety symptoms, cancer worry (CWS), self-efficacy, and cancer-specific distress (secondary).

2 METHODS

2.1 Study design and participants

The CORRECT trial was a two-arm, parallel, blocked, multicenter randomized controlled trial (RCT) that evaluated the efficacy of the CORRECT intervention (bCBT) compared with CAU in distressed patients who had completed primary curative treatment for CRC. The study protocol has been published16 and the study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethical review board of the Radboud university medical center (CMO Arnhem-Nijmegen # NL55018.091.15). All participants provided written informed consent.

Eligible participants were adults who were cancer free when entering the study, had completed primary CRC treatment with curative intent (stage I, II or III) between 6 months (time to readapt) and 5 years prior to enrollment (being in active medical follow-up), with a distress level of ≥5 as measured on the Distress Thermometer (range 0–10), had internet access at home and possessed an email address, were literate in Dutch and able to travel to the academic hospital for face-to-face sessions. Exclusion criteria for the trial were a diagnosis of Lynch Syndrome or current active psychotherapeutic treatment.

Eligible CRCS were enrolled through four recruitment methods between August 2016 and March 2020. At trial launch, potentially eligible CRCS were retrospectively selected by database screening of seven hospitals in the Netherlands or were prospectively approached by their treating nurse or physician at routine follow-up visits within four hospitals. Study information was provided with the option to indicate interest in participation by sending back contact information or reject participation and optionally declare a reason for rejection. Additionally, in a later phase of the trial, CRCS who were registered at the Prospective National CRC Cohort (“Prospectief Landelijk CRC (PLCRC) cohort”) were selected for eligibility and received study information with information on how to participate in the trial. Finally, information about the trial was posted on social media (i.e., the study's Facebook and Twitter pages), newsletters and flyers in hospital waiting rooms and cancer community services. Interested patients could contact the researchers via e-mail or telephone. They were sent a secure weblink to the digital screening questionnaires via e-mail or received hard-copy screening measures via regular mail (according to patient preferences). After screening, a member from the research team contacted the patient by phone to address questions and confirm eligibility criteria. During this telephone screening the researcher also checked the self-perceived need for help by asking if the patient believed they had problems worth talking about to a psychologist. After written informed consent was obtained, the researcher sent participants a secure weblink to the baseline measures via e-mail or a paper version via mail.

2.2 Randomization and masking

Randomization with a 1:1 ratio occurred after participants had completed their baseline measures. The CORRECT trial was a blocked RCT because eligible participants were first stratified based on the regional academic hospital of enrollment (Radboudumc or Amsterdam UMC), sex (male or female) and cancer diagnosis (colon or rectal), and then randomized into intervention arm or CAU using blocks of 2 to 4 participants (varying). A unique identification code for each participant and stratification variables for eligible participants were entered in an online, custom-built randomization program developed by an employee not involved in the study. The program provided immediate randomization. Randomized participants received notification of the intervention or CAU assignment by phone and mail. Those allocated to the intervention also received an invitation for an appointment with one of the psychologists. Participants and research staff were not masked to intervention status, which is common in trials of psychological interventions17 and understood as part of the intervention, similar to clinical practice. The statistician responsible for analyses was blinded for intervention status.

2.3 Intervention

The CORRECT intervention was an individual bCBT intervention that consisted of five face-to-face sessions (sessions 1, 2, 3, 5 and 8; 1 hour) at one of the two academic hospitals (Radboudumc or Amsterdam UMC) and three telephone consultations (sessions 4, 6 and 7; 15 min). The intervention sessions started between 1- and 2-weeks post-randomization and were scheduled in a period of 14 weeks, during which participants also had access to an online intervention website. Participants were registered on the website and received an invitation link via email to activate their account. If participants were unable to use the online program, they received a paper workbook and USB-key with videos, which was identical in content. Detailed information on the intervention and website development is available in the study protocol and published case study.16, 18 For session overviews, see online supplementary material. In short, therapy sessions included psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring, behavior modification and relaxation. Therapy content targeted three types of distress in different modules: (1) distress due to physical consequences (gastrointestinal problems, stoma-related issues, post-cancer fatigue, neuropathy, pain and sexual dysfunction), (2) anxiety and uncertainty, and (3) depressive mood. Participants and psychologists selected one or two modules based on problem areas identified via baseline questionnaire scores and patient needs, but patients had access to all three modules. After every session, relevant assignments were selected and made available to the participant within the chosen module(s) on the website. Assignments consisted of different types of self-management activities, including reading psycho-educational scripts, completing tasks, screening tests, audio clips, and peer videos.

Five registered health care psychologists with at least 5 years of experience in the field of medical psychology and psycho-oncology provided the intervention. Therapists followed a 2-day training with a researcher and a senior clinical psychologist (JP) to ensure therapist competence and fidelity to the treatment protocol, and a one-hour training in using the intervention website. After the training, biweekly group supervisions took place with the senior clinical psychologist (JP). Treatment sessions were audio recorded, and a randomly selected sample of two face-to-face sessions per therapist (9% of all sessions) were audited for adherence to planned session components.19

Participants randomized to CAU received questionnaires to obtain trial outcomes but did not have access to the bCBT program. There were no restrictions to the use of psychological services and treatments after trial entry for participants receiving CAU.

2.4 Measures

Demographic information was obtained through online self-report questionnaires and medical information through medical records. Participants completed outcome measures at baseline (T0), and four (T1) and 7 months (T2) after baseline. Detailed information on outcome measures is available in the online supplementary material.

The primary outcome was psychological distress measured with the 18-item Brief Symptom Inventory-18 (BSI-18)20 at T1. A total score is calculated (primary), as well as three subscales for anxiety, depression, and somatization (secondary). Higher scores reflect more distress.

Secondary outcomes were BSI-18 total score at T2 and BSI-18 subscale scores and other outcomes at T1 and T2 months follow-up, including the perceived impact of physical consequences of colorectal cancer (European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30; EORTC-QLQ-3021, 22 and the 38-item colorectal cancer specific module; CR3823); fatigue (20-item Checklist Individual Strength (CIS)24); anxiety and depression symptoms (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)25); fear of cancer recurrence (Cancer Worry Scale; CWS26); cancer specific distress (Impact of Event Scale; IES27), and self-efficacy (Self-Efficacy Scale28).

Three key aspects of the therapeutic relationship (agreement on the tasks of therapy, agreement on the goals of therapy, and development of an affective bond) were assessed with the short form of the Working Alliance Inventory (WAI-S29) questionnaire at T1.

Overall treatment satisfaction, efficacy and user-friendliness of the intervention was assessed at T1 with an intervention evaluation questionnaire with purpose-designed items scored on 5-, 6- or 10-point scales with higher scores indicating more positive evaluations. Additionally, items about utility of different components of the intervention were answered on 4- or 6-point scales. Website usability was assessed with the System Usability Scale (SUS30), with higher scores indicating a better perception of the website usability.

2.5 Statistical analyses

Based on reviews and meta-analyses of psychosocial and cognitive behavioral interventions in cancer survivors, we assumed a standardized mean difference effect size of 0.4.31-34 For a two-tailed alpha of 0.05, and an assumed correlation of 0.6 between pre- and post-intervention assessments,35 N = 128 provides at least 80% power. Assuming 20% loss to follow-up, we targeted to include at least 160 participants.

All outcome analyses were conducted in R (R version 3.6.3; R Studio version 1.2.5042). We used an intent-to-treat analysis to estimate score differences between all patients randomly assigned to the CORRECT intervention and to CAU using a linear regression model (using the lm function in R). In main analyses we adjusted for baseline score, and to account for the stratification approach, sex, hospital and tumor location were adjusted for as well.

To minimize the possibility of bias from missing outcome data, we used multiple imputation by chained equations using the mice package to generate 20 imputed datasets, using 15 cycles per imputed dataset. Variables in the mice procedure included intervention arm, psychologist, number of intervention sessions attended, sex (female vs. male), hospital (Amsterdam UMC vs. Radboudumc), tumor location (rectal vs. colon), measures of all primary and secondary outcomes (only subscale scores for variables analyzed with total scores and subscales) at baseline and 4- and 7-months follow-up, age, years since end of treatment, and recruitment method (self-referral vs. retrospective vs. prospective vs. PLCRC Cohort). Pooled standard errors and associated confidence intervals were estimated using Rubin's rules. To aid in the interpretation of study results, for primary and secondary outcomes, at 4- and 7-months follow-up, we produced standardized mean differences (Hedges' g).

As a secondary analysis of the primary outcome (BSI-18), we also controlled for age (years), and years since end of treatment. Analyses of secondary outcomes were similar1 controlling for baseline scores and stratification variables only and2 controlling for baseline scores, stratification variables, and additional covariates.

To estimate average intervention effects among compliers (defined as attending at least 2 of 8 sessions), we used an instrumental variable approach to inflate intention-to-treat effects from main models by the inverse probability of compliance among intervention group participants (complier-average causal effect analysis) for the primary outcome (BSI-18 total scores) and BSI-18 subscale scores.

Post-hoc analyses were added to explore whether model fit (based on Akaike Information Criteria) was improved after accounting for possible differences in intervention effect for the various psychologists who administered the intervention, for the primary outcome (BSI-18 total scores). To do this, we fitted additional linear regressions where we used the control group as the reference group and computed treatment effects for each psychologist in complete case analyses.

The reliable change index (RCI) was calculated for participants who completed both T0 and T1 BSI-18 total scores to determine the statistical reliability of difference scores.36 The RCI represents the change between and individual's T0 and T1 scores divided by the standard error of difference between the scores resulting in reliable improvement (RCI < −1.96), no reliable change (RCI −1.96 to 1.96) or reliable deterioration (RCI > 1.96).

Secondly, clinically significant change (CSC) was defined as a decrease of the BSI-18 total score to the normal range (BSI-18 < 10 for men; BSI-18 < 13 for women20). Participants were classified as clinically significantly improved if both criteria were met (RCI < −1.96 and CSC).

2.6 Protocol amendments

Protocol amendments are described in the online supplementary material.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Participants

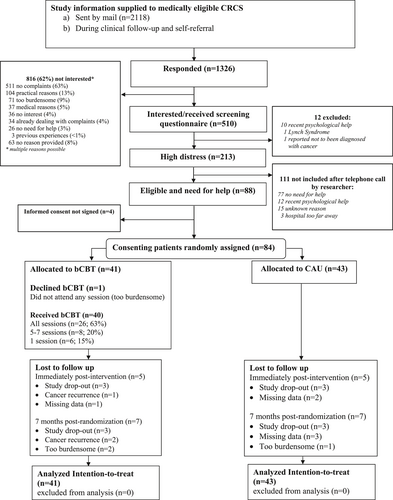

Between August 2016 and March 2020, 84 participants were enrolled (53% of targeted sample size). Enrollment was stopped before reaching the targeted sample size of 160 participants because enrollment of a substantial number of additional participants was unlikely given a participation rate of only 4% of medically eligible patients. Details about reasons for non-participation are described in detail elsewhere.37

Of the 84 participants, 41 (49%) were allocated to the intervention, and 43 (51%) to CAU (See Figure 1). As shown in Table 1, demographic and disease characteristics of intervention and CAU participants were similar. Overall, mean age was 63.7 years (SD = 9.3) and 58% (n = 49) were female. Participants were recruited retrospectively through hospital registries (58%; n = 49), prospectively during routine visits (24%, n = 20), the PLCRC Cohort (16%; n = 13), and self-referral (2%; n = 2). Mean time since the end of curative treatment was 2.2 years (SD = 1.3 years), and 70% of participants had colon cancer (n = 59).

CONSORT flow chart showing recruitment and enrollment of 84 participants.

| Variable | CORRECT intervention (N = 41) | Care as usual control (N = 43) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic | ||

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 62.5 (9.5) | 64.9 (9.1) |

| Female sex, N (%) | 17 (41.5%) | 18 (41.9%) |

| Level of education completed, N (%) | ||

| Primary | 10 (24.4%) | 6 (14.0%) |

| Secondary | 16 (39.0%) | 16 (37.2%) |

| Tertiary | 15 (36.6%) | 21 (48.8%) |

| Partnered, N (%) | 31 (77.5%)a | 40 (95.2%)b |

| Hospital, N (%) | ||

| Radboudumc | 34 (82.9%) | 34 (79.1%) |

| Amsterdam UMC | 7 (17.1%) | 9 (20.9%) |

| Recruitment method, N (%) | ||

| Self-referral | 2 (4.9%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Retrospective (via hospital registries) | 22 (53.7%) | 27 (62.8%) |

| Prospective (routine hospital visits) | 11 (26.8%) | 9 (20.9%) |

| Prospective Dutch colorectal cancer (PLCRC) cohort | 6 (14.6%) | 7 (16.3%) |

| Time since end of treatment in years, mean (SD) | 2.1 (1.3) | 2.4 (1.4) |

| Colon cancer, N (%) | 29 (70.7%) | 30 (69.8%) |

| Number of comorbid diseases | ||

| 0 | 4 (9.7%) | 6 (13.9%) |

| 1–2 | 26 (63.4%) | 29 (67.4%) |

| 3+ | 11 (26.8%) | 8 (18.6%) |

| Psychological help in the past | ||

| Yes | 24 (58.5%) | 20 (46.5%) |

| No | 11 (26.8%) | 13 (30.2%) |

| Unknown | 6 (14.6%) | 10 (23.3%) |

| Patient-reported outcomes (baseline) | ||

| BSI-18 total score, mean (SD) | 13.6 (7.7) | 13.3 (8.0) |

| BSI-18 depression score, mean (SD) | 4.6 (3.6) | 4.9 (3.8) |

| BSI-18 anxiety score, mean (SD) | 5.1 (4.1) | 4.7 (3.7) |

| BSI-18 somatization score, mean (SD) | 3.9 (2.6) | 3.7 (3.2) |

| EORTC-QLQ-C30 summary score, mean (SD) | 74.0 (12.2) | 74.7 (12.0) |

| Fatigue (CIS) score, mean (SD) | 38.6 (11.2) | 38.0 (9.5) |

| HADS total score, mean (SD) | 15.5 (6.6) | 15.5 (6.4) |

| HADS anxiety subscale (HADS-A) score, mean (SD) | 8.2 (4.2) | 8.2 (3.5) |

| HADS depression subscale (HADS-D) score, mean (SD) | 7.3 (3.5) | 7.3 (3.8) |

| Fear of cancer recurrence (CWS) score, mean (SD) | 16.1 (4.9) | 15.2 (4.4) |

| Cancer-specific distress (IES) total score, mean (SD) | 20.9 (16.7) | 19.9 (17.5) |

| IES avoidance subscale score, mean (SD) | 9.7 (8.6) | 11.4 (10.5) |

| IES intrusion subscale score, mean (SD) | 11.1 (9.1) | 8.4 (8.1) |

| Self-efficacy (SES) score, mean (SD) | 18.0 (2.4) | 18.6 (1.9) |

- Abbreviations: BSI-18, Brief Symptom Inventory-18; CIS, Checklist Individual Strength; CWS, Cancer Worry Scale; EORTC-QLQ, European Organization for Research and Treatment for Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; IES, Impact of Event Scale; SES, Self-efficacy Scale.

- Due to missing values:

- a N = 40.

- b N = 42.

3.2 Intervention sessions

The mean number of sessions attended was 6.3 (SD = 2.7); 1 (2%) participant enrolled but did not attend any sessions, 6 (15%) attended 1 session, 8 (20%) attended 5–7 sessions, and 26 (63%) attended all 8 sessions. In the 10 sessions evaluated for planned treatment adherence, 91% (range: 30%–100%) of the time spent in therapy was relevant for bCBT and 90% (range: 57%–100%) of the sessions covered all required session components.

3.3 Trial outcomes

Outcome data were obtained for 88% (74 of 84) of participants immediately post-intervention, including 36 of 41 (88%) of intervention participants and 38 of 43 (88%) from CAU. At 7 months post-randomization, 88% (70 of 88) provided follow-up data, including 83% (34 of 41) of intervention and 84% (36 of 43) of CAU participants. Overall, 82% (69 of 84) participants completed measures at all 3 time points. Table 2 shows complete-data outcomes at each time point.

| Immediately post-intervention | 7 months post-randomization | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CORRECT intervention (N = 36) | Care as usual control (N = 38) | CORRECT intervention (N = 34) | Care as usual control (N = 36) | |

| BSI-18 total score, mean (SD) | 6.7 (6.8) | 11.6 (9.0) | 5.7 (6.0) | 10.0 (9.6) |

| BSI-18 depression score, mean (SD) | 2.5 (3.6) | 4.0 (3.9) | 1.7 (2.5) | 3.5 (4.2) |

| BSI-18 anxiety score, mean (SD) | 2.2 (2.4) | 4.7 (4.6) | 2.0 (3.2) | 3.6 (4.1) |

| BSI-18 somatization score, mean (SD) | 2.0 (2.2) | 3.0 (3.1) | 2.0 (2.0) | 2.9 (3.0) |

| EORTC-QLQ-C30 summary score, mean (SD) | 83.6 (12.0) | 78.2 (14.9) | 86.6 (9.2) | 80.9 (13.4) |

| Fatigue (CIS) score, mean (SD) | 32.8 (11.7) | 35.3 (9.7) | 31.4 (11.0) | 33.4 (11.4) |

| HADS total score, mean (SD) | 10.9 (6.7) | 14.7 (6.9) | 9.2 (5.3) | 13.6 (6.8) |

| HADS anxiety subscale (HADS-A) score, mean (SD) | 5.6 (3.3) | 8.0 (4.2) | 4.5 (3.0) | 7.3 (3.8) |

| HADS depression subscale (HADS-D) score, mean (SD) | 5.2 (4.0) | 6.7 (3.5) | 4.7 (3.4) | 6.3 (3.9) |

| Fear of cancer recurrence (CWS) score, mean (SD) | 13.1 (3.7) | 15.3 (4.9) | 12.9 (3.0) | 14.5 (4.6) |

| Cancer-specific distress (IES) total score, mean (SD) | 11.5 (12.6) | 21.4 (17.2) | 12.8 (12.4) | 20.3 (16.9) |

| IES avoidance subscale score, mean (SD) | 5.5 (7.4) | 11.4 (9.5) | 6.6 (7.2) | 10.6 (9.1) |

| IES intrusion subscale score, mean (SD) | 5.9 (6.1) | 10.0 (9.0) | 6.1 (6.4) | 9.7 (8.9) |

| Self-efficacy (SES) score, mean (SD) | 19.5 (2.3) | 18.9 (2.5) | 20.0 (2.3) | 18.3 (2.8) |

- Abbreviations: BSI-18, Brief Symptom Inventory-18; CIS, Checklist Individual Strength; CWS, Cancer Worry Scale; EORTC-QLQ, European Organization for Research and Treatment for Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; IES, Impact of Event Scale; SES, Self-efficacy Scale.

As shown in Table 3, in the primary intent-to-treat analysis, BSI-18 scores were statistically significantly different between groups immediately post-intervention. Post-intervention scores were 3.86 points lower (95% CI −7.00 points to −0.73 points) for intervention compared to CAU. Results were similar when adjusted for covariates. In average complier effect analysis, BSI-18 total scores were 4.63 points lower (95% CI −8.53 to −0.73 points) for intervention compared to CAU participants. At 7 months post-randomization, in the main intent-to-treat analysis, distress scores were significantly lower in the intervention arm compared to CAU (−3.88 points, 95% CI −6.95 to −0.80 points), including when adjusted for covariates. In average complier effect analysis, BSI-18 total scores were 4.65 points lower (95% CI −8.56 to −0.74 points). See Table 3.

| Intent to treata post-intervention | Intent to treata | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 months post-randomization | ||||

| Difference (95% CI) | Hedge's g SMD (95% CI) | Difference (95% CI) | Hedge's g SMD (95% CI) | |

| Primary outcome | ||||

| BSI-18 total scores | −3.86 (−7.00 to −0.73) | −0.46 (−0.83, −0.08) | −3.88 (−6.95 to −0.80) | −0.46 (−0.83, −0.09) |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||

| BSI-18 depression subscale score | −0.89 (−2.31, 0.52) | −0.23 (−0.59, 0.14) | −1.49 (−2.85 to −0.13) | −0.41 (−0.78, −0.03) |

| BSI-18 anxiety subscale score | −2.01 (−3.49 to −0.52) | −0.50 (−0.87, −0.13) | −1.26 (−2.72 to 0.19) | −0.33 (−0.70, 0.05) |

| BSI-18 somatization subscale score | −0.94 (−2.09, 0.21) | −0.33 (−0.74, 0.08) | −1.09 (−2.38 to 0.20) | −0.37 (−0.81, 0.07) |

| HADS total scores | −3.53 (−5.91 to −1.15) | −0.51 (−0.85, −0.16) | −4.09 (−6.62 to −1.56) | −0.62 (−1.02, −0.23) |

| HADS-D score | −1.45 (−2.84 to −0.06) | −0.38 (−0.74, −0.01) | −1.71 (−3.38 to −0.05) | −0.44 (−0.86, −0.02) |

| HADS-A score | −2.09 (−3.45 to −0.72) | −0.53 (−0.88, −0.17) | −2.38 (−3.72 to −1.03) | −0.64 (−1.01, −0.27) |

| EORTC-QLQ-C30 score | 4.95 (−0.07 to 9.97) | 0.36 (−0.01, 0.73) | 5.26 (0.87 to 9.64) | 0.43 (0.07, 0.79) |

| CIS score | −2.49 (−6.73 to 1.74) | −0.23 (−0.62, 0.16) | −2.27 (−6.90 to 2.36) | −0.20 (−0.59, 0.20) |

| CWS score | −2.25 (−3.70 to −0.80) | −0.50 (−0.83, −0.17) | −1.64 (−2.99 to −0.30) | −0.41 (−0.75, −0.07) |

| IES score | −8.59 (−13.53 to −3.66) | −0.54 (−0.86, −0.22) | −5.99 (−11.54 to −0.44) | −0.39 (−0.75, −0.02) |

| IES intrusion score | −4.58 (−7.21 to −1.95) | −0.57 (−0.91, −0.23) | −3.90 (−6.83 to −0.98) | −0.48 (−0.84, −0.12) |

| IES avoidance score | −3.98 (−6.69 to −0.99) | −0.44 (−0.77, −0.10) | −2.22 (−5.47 to 1.04) | −0.26 (−0.64, 0.12) |

| SES score | 1.51 (0.49 to 2.52) | 0.59 (0.19, 0.99) | 1.85 (0.64 to 3.06) | 0.65 (0.21, 1.08) |

- Abbreviations: BSI-18, Brief Symptom Inventory-18; CIS, Checklist Individual Strength; CWS, Cancer Worry Scale; EORTC-QLQ, European Organization for Research and Treatment for Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; IES, Impact of Event Scale; SES, Self-efficacy Scale.

- a controlled for baseline score + stratification variables (sex, hospital, and tumor location).

Among other secondary outcomes, at T1 and T2, distress (HADS total), as well as depression symptoms (HADS-D) and anxiety symptoms (HADS-A), CWS, and cancer specific distress (IES) were significantly lower in the intervention arm compared to CAU. Self-efficacy scores were significantly higher in the intervention arm compared to CAU. BSI-18 anxiety scores were lower in the intervention arm compared to CAU at T1 but not T2, whereas BSI-18 depression scores were statistically significantly lower at T2 but not T1. Quality of life (EORTC-QLQ-30) scores were statistically significantly higher in the intervention arm compared to CAU at T2 but not T1. See Table 3.

Results from complete case analyses are provided in the online supplementary material. Results of complete case analyses and intent-to-treat analyses were similar. In post-hoc analyses, including the treating psychologist in the model did not lead to improved model fit.

3.4 Clinical relevance

Although the proportion of participants reporting reliable improvement, CSC and clinically significant improvement was higher in bCBT compared with CAU, the difference was not statistically significant (Table 4). One participant in the CAU condition reported a clinically significant increase in distress.

| Criteria | bCBT (N = 36) | CAU (N = 38) | Fishers' exact test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reliable change: Improvement | 9 (25%) | 4 (11%) | p = 0.136 |

| Clinically significant change | 16 (44%) | 9 (24%) | p = 0.085 |

| Clinically significant improvement | 9 (25%) | 4 (11%) | p = 0.132 |

3.5 Satisfaction with the intervention

Overall treatment satisfaction was high (mean = 7.4/10, n = 36) and 94% of participants indicated that they would recommend the intervention to other colorectal cancer patients. Subjective efficacy was rated as good (3.8/5.0, n = 34), as 75% felt helped by the intervention and most patients reported major improvement (65%) or no distress at all (16%) at T1. Overall usefulness of treatment components was rated as very useful (3.6/4.0, n = 30). Detailed information is provided in the Appendix.

SUS scores showed an overall user-friendliness of the CORRECT website of 36.6/50. Participants (n = 32) reported to have visited the online modules at least once a week (n = 13, 41%), at least once a month (n = 9, 28%) or a few times at most (n = 10, 31%) during the intervention period.

Patients in the intervention arm rated the therapeutic relationship overall as high with mean WAI scores of 4.1/5 (n = 32, 78%). The subscales agreement on therapy tasks, agreement on goals, and affective bond scored very good or high with mean scores of 3.9, 4.1, and 4.3, respectively.

4 DISCUSSION

We tested a blended CBT intervention and found statistically significant lower scores on distress in intervention participants compared with CAU immediately post-intervention and at 7-months follow-up in CRCS with severe distress. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first RCT to demonstrate effects of a bCBT intervention on distress reduction in distressed CRCS. Secondary outcomes concerning quality of life, general and cancer-specific distress, fatigue, fear of cancer recurrence and self-efficacy confirmed the positive effects of bCBT with small to medium effect sizes. These effect sizes are comparable to effect sizes found in a meta-analysis on psycho-oncological face-to-face interventions for individual therapies on emotional distress in mixed cancer survivors (d = 0.35).31 They were somewhat smaller than a recent bCBT for high fear of cancer recurrence.38 Although a higher proportion of patients receiving bCBT reported CSC, this was not statistically different from the CAU condition. Our conclusions about the effectiveness of the CORRECT intervention are limited by the inability to meet our targeted recruitment for the trial (84 of 128 participants required for adequate power not considering loss-to follow-up (65%) and of 160 targeted (53%)).

Only CRCS with high distress were eligible to participate in the study. Fewer CRCS than anticipated (based on previous studies) experienced high distress (48%), and there was a low participation rate in our trial (4% of eligible CRCS).37 In addition, only 60% of CRCS who scored above the cut-off of the Distress Thermometer (≥5) reported a need for help from a psychologist. This could be because distress is a generic concept consisting of multiple components including a physically oriented component for which patients might preferably contact other healthcare professionals. Compared to the Dutch CRC population, the distribution of sex and tumor location was similar (male: 58% vs. 56%; colon 68% vs. 71%), but the proportion of patients above the age of 70 was substantially lower (24% vs. 53%), in line with previous studies.39-41 Furthermore, 88% of CRCS reported at least one comorbidity, 23% reported three or more comorbidities and half of CRCS had received psychological help in the past. Taken together, this suggests that there is a relatively small, selected sample of CRCS requiring a psychological intervention such as CORRECT.

Regarding the feasibility of CORRECT, the intervention non-completion rate was 37%, of which 20% participated in 5–7 sessions. Therapist treatment adherence was high with 90% coverage of bCBT elements and all required session components. Patients were highly satisfied with the treatment, would recommend the intervention to other CRCS and rated subjective efficacy as good. The CORRECT website was rated as user friendly and the therapeutic relationship as high. These feasibility outcomes support implementation, and a next step would be to investigate how CORRECT fits in the real-world psycho-oncological setting. As the fit of interventions within the real-world care is highly context-specific, barriers and facilitators for implementation should be explored in addition to the healthcare setting in which CORRECT could be optimally embedded. The trial was conducted in two academic hospitals, but regional hospitals as well as psycho-oncological centers could also provide this psychological intervention.

4.1 Clinical implications

Based on the results of this study, clinically, a matched care model should be considered in which distress as a normal reaction to a cancer diagnosis and treatment would be emphasized by the medical team, providing patients with skills to address mild distress and help prevent the development of severe distress. For those experiencing elevated feelings of distress, interventions varying in intensity along distress severity in relation to the nature of emotions (adaptive vs. maladaptive) following a matched care model might be most optimal: low-intensity supportive interventions in case of elevated distress and adaptive emotions, and professional mental health care such as the CORRECT intervention in case of high distress and maladaptive emotions.42

4.2 Study limitations

This study has several limitations. First and foremost, because of the inability to meet the targeted recruitment for the trial and the small inclusion rate, conclusions about the effectiveness and generalizability of the CORRECT intervention warrant caution. Furthermore, CORRECT was designed to tailor intervention content to meet individual treatment goals using different treatment modules. However, no insight in working mechanisms was obtained so conclusions on key elements could not be made, neither on key elements nor dose relationship of the website as there was no information on website usage. Lastly, we did not investigate a potential relationship between the treatment effect and use of pharmacological interventions or psychosocial services. This limits conclusions about CORRECT being the main or only element in distress improvement.

5 CONCLUSIONS

In sum, we found a statistically significant reduction in distress severity amongst distressed CRCS treated with CORRECT. However, uncertainty about the effectiveness remains, due to smaller than planned sample size. Interventions such as CORRECT might be a useful tool to address mental health needs in a select vulnerable group of CRCS.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Judith Prins, Joost Dekker, Annemarie Braams, Belinda Thewes and Johannes de Wilt contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by José Custers, Linda Kwakkenbos, Brooke Levis, Yvonne van der Hoeven, Lynn Leermakers, and Sarah Döking. The first draft of the manuscript was written by José Custers and Linda Kwakkenbos and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The CORRECT trial was funded by the Dutch Cancer Society (grant number KUN 2014–7155) The funding body has no role in collecting, analyzing or interpreting data of the trial. We thank Marieke Gielissen for her role in co-designing the study, as well as the following therapists who provided the CORRECT intervention: Dr. Emma Collette (coordinating therapist), Marieke de Gier, MSc, and Carien Brals-Koomen, MSc, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam, the Netherlands; and Dr. Saskia Spillekom – van Koulil, Dr. Petra Servaes, Dr. Nienke Tielemans, Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

ETHICS STATEMENT

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.