Colorectal cancer survivors' experiences and views of shared and telehealth models of survivorship care: A qualitative study

Penelope Schofield and Michael Jefford have equal senior authors.

Abstract

Objectives

The number of colorectal cancer (CRC) survivors is increasing and current models of survivorship care are unsustainable. There is a drive to implement alternative models of care including shared care between general practitioners (GPs) and hospital-based providers. The primary objective of this study was to explore perspectives on facilitators and barriers to shared care. The secondary objective was to explore experiences of telehealth-delivered care.

Method

Qualitative data were collected via semi-structured interviews with participants in the Shared Care for Colorectal Cancer Survivors (SCORE) randomised controlled trial. Interviews explored patient experiences of usual and shared survivorship care during the SCORE trial. In response to the COVID pandemic, participant experiences of telehealth appointments were also explored. Interviews were recorded and transcribed for thematic analysis.

Results

Twenty survivors of CRC were interviewed with an even number in the shared and usual care arms; 14 (70%) were male. Facilitators to shared care included: good relationships with GPs; convenience of GPs; good communication between providers; desire to reduce public health system pressures. Barriers included: poor communication between clinicians; inaccessibility of GPs; beliefs about GP capacity; and a preference for follow-up care with the hospital after positive treatment experiences. Participants also commonly expressed a preference for telehealth-based follow-up when there was no need for a clinical examination.

Conclusions

This is one of few studies that have explored patient experiences with shared and telehealth-based survivorship care. Findings can guide the implementation of these models, particularly around care coordination, communication, preparation, and personalised pathways of care.

1 BACKGROUND

In 2021, colorectal cancer (CRC) was the second most commonly diagnosed cancer affecting both men and women in Australia and third most common in the United States.1, 2 With advances in early detection and treatments, survival rates are increasing, with around 70% of those diagnosed surviving 5 years in Australia and the USA.2, 3 Survivors may, however, continue to experience broad physical and psychosocial long-term effects,4 including fatigue,5 bowel,6 and sexual dysfunction,7 depression and anxiety.8 Traditionally, survivorship care has been face-to-face, oncologist-led follow-up focusing on surveillance and symptom management.9, 10 This model, however, is associated with significant unmet needs9-13 and does not reflect optimal cancer survivorship care, particularly regarding coordination between specialist cancer care teams and primary care providers.13 Specialist-led care is also unsustainable as cancer survivorship and demands on hospital resources increase.9, 10

With more physical and psychological health problems, cancer survivors visit their general practitioners (GPs) more often than people without cancer.14 GPs are well positioned to play a role in survivorship care because of their understanding of patients' medical histories and needs,12, 15 capacity to promote cancer surveillance, manage comorbid illness, and provide psychosocial support, health promotion, and care coordination.15, 16 Research into the effectiveness of shared survivorship care between oncologists and GPs is limited and there have been no published randomised controlled trials (RCT) examining shared care for CRC survivors. Systematic reviews including mixed-cancer types have found no significant differences between specialist-led and shared models of survivorship care for quality of life,17 surveillance and psychosocial effect management,18 care satisfaction,17 and detecting cancer recurrence.17 Shared care yielded higher patient satisfaction,17 improved primary-secondary cancer care coordination,18 and is potentially more cost effective than specialist-led care.17

Despite the feasibility and apparent effectiveness of shared care, CRC survivorship care in Australia continues to focus on specialist-led cancer surveillance, with insufficient attention on survivors' other needs.11, 19 Studies that have included CRC survivors' perspectives on proposed shared care models are mixed. Participants believed their GPs should perform routine monitoring and cancer screening tests,20 and also deliver holistic care and psychosocial support, which might not be adequately addressed in specialist care settings.20, 21 However, participants were concerned about information communication between providers.21-23 Participants with confidence in their GP's skills, knowledge and communication more readily considered their GP as their ideal follow-up care provider.23

There are few RCTs of shared care and uptake of this model is negligible,12, 24 possibly reflecting the scant evidence about implementation.25 Often successful implementation is determined by clinical outcome data. This focus hinders understanding of the process of implementation and related contextual factors.26 Several guiding frameworks in implementation science exist.27, 28 Proctor et al26 propose several implementation outcomes including acceptability, appropriateness, feasibility and sustainability among others. Their framework is favoured by some researchers as it clearly differentiates implementation from clinical and service outcomes.27 Successful implementation of shared survivorship care may be informed by intervention effectiveness and implementation outcomes as defined by Proctor et al.26

The SCORE RCT was designed to evaluate shared care for CRC survivors.29 In this trial, patients with early-stage colon or rectal cancer treated with curative intent were randomised to usual care follow-up (hospital-based visits 3, 6, 9 and 12 months following end of treatment) or to shared care, which substituted the 3 and 9 month visits with GP visits and added an early GP visit soon after treatment ended. As part of the shared care intervention, participants received additional resources including a survivorship care plan (SCP), a patient information booklet and DVD, and a concerns/question prompt list. GPs received clinical management guidelines and the SCPs. SCORE was conducted at five public hospitals in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. The trial was disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic with follow-up care shifting from face-to-face to telehealth consultations in both arms of the study.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, telehealth visits were fundamental to enable ongoing cancer care delivery.30, 31 Telehealth is time- and cost-effective for health workers and patients,32 has high patient satisfaction rates,33 and can improve access to oncology specialists.30 However, some clinicians are concerned that increased telehealth use may adversely impact patient outcomes, including impaired communication and absence of physical examination.31 Therefore, in-person consultations may be preferred for delivering crucial information, when physical examination is necessary and for patients with cognitive impairments or limited health literacy.34

Our study formed part of the SCORE trial evaluation.29 Its primary objective was to explore patients' perspectives on facilitators and barriers to implementing the shared care model for CRC survivors. The secondary objective was to explore patients' experiences receiving survivorship care via telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic. To our knowledge, there has been no qualitative investigation into CRC survivors' experiences of a controlled shared care intervention, and this study will inform future implementation of this model of care.

2 METHOD

2.1 Design

The constructivist approach, which asserts that reality perception is constructed from individual and socio-historical contexts,35 informed this qualitative study. A thematic analysis was conducted, guided by selected grounded theory techniques including constant comparative, iterative, concurrent data collection and analysis, and predominantly inductive analysis.36 While grounded theory is a contested approach,35 the “Strauss” led approach supports using grounded theory techniques to develop themes.37

2.2 Participants

Purposive sampling was used whereby only SCORE trial participants who expressed willingness (via consent-form tick-box) to participate in an interview about their experiences on study completion (12 months) were invited. Eligible participants were invited via email or letter, provided with an information statement, and followed up via phone call. Participant consent was verbal and audio recorded on interview commencement. Participants were selected to ensure even distribution between those allocated to the shared and usual care arms of the SCORE trial, and to ensure representation across all enrolling hospital sites.

2.3 Data collection

SCORE trial investigators29 developed two sets of semi-structured interview guides, with a shared care set specific for participants in the shared care arm, and a usual care set specific for participants in the usual care arm (Appendices 1 and 2). Development of these guides was informed by implementation outcomes relevant to the individual consumer level, as defined by Proctor et al.26 and aimed to understand the acceptability and appropriateness of the SCORE shared care intervention from the patients' perspectives, and their preferences for follow-up care. Audio-recorded interviews were conducted by the lead author (CG) between August 2021 and August 2022 either via video or telephone. CG is a registered psychologist and was trained in research interviewing techniques by PS, an experienced qualitative research interviewer. The interview for shared care participants explored their experiences of shared care and follow-up care preferences. The interview for usual care participants explored their experiences of usual care and attitudes towards greater GP involvement. All interviews explored participant experiences of receiving telehealth-delivered care during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2.4 Data analysis

Audio-recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim. Initial analysis (CG) involved open coding, with labels created to describe segments of transcript content. Codes with similar meaning were grouped into categories.38 Similarities, differences, and relationships across categories were considered to inform the theme names, aligned with the study goals.38 NVivo software (QSR International Pty Ltd) supported data management.

CG coded all transcripts and a subset of five transcripts were reviewed and co-coded by an experienced qualitative researcher (CW) to improve analytic trustworthiness. CG and CW first met after each coding the initial transcript and compared perspectives on the codes. CW supported CG's approach to coding. Throughout the analysis, CG and CW met to review and define emerging categories and themes within the data. Minor differences were reconciled upon discussion. This method of inter-rater analysis was employed to increase interpretative rigour.39

Demographic information was extracted from the interviews and summarised using descriptive statistics.

Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative data (COREQ)40 were adhered to, although ‘participant checking’ was conducted through inviting participant feedback on the interviewer's summary of their statements at the end of interviews. This ‘participant checking’ conversation was included in the verbatim transcription. All participants confirmed their experiences had been captured accurately, and were able to elaborate, or clarify, as necessary. Overall findings were not returned to participants due to potential burden41; and no available evidence indicates that the strategy improves the quality of findings.42

2.5 Ethics

Ethics approvals were received from Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre (Ref: HREC/72311/PMCC-2020) and Swinburne University (Ref: 20215904-8162) ethics committees.

3 RESULTS

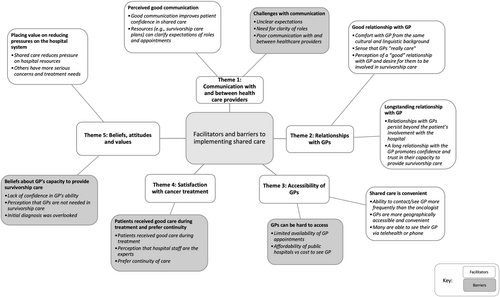

Twenty participants (70% male) were interviewed with an even distribution between the shared and usual care arms of the SCORE trial (Table 1). Thirty-one were invited, nine did not respond and two declined (hearing impairment and psychosocial stressors). Participants' median age was 60.5 years (range: 36–86-years-old). Findings were organised into two sets of themes relating to facilitators and barriers to implementing shared care (Figure 1 and Appendix 3) and perspectives on using telehealth-delivered care (Appendix 4).

| Participant ID | Age (in decadesa) | Sex | Study arm | Hospital | Telehealth experiences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1S | 30s | F | Shared | Austin | Hospital: Phone/F2F |

| GP: F2F | |||||

| P2U | 40s | M | Usual | Austin | Hospital: Phone/video/F2F |

| P3S | 40s | M | Shared | Austin | Hospital: Phone/F2F |

| GP: F2F | |||||

| P4S | 40s | M | Shared | Austin | Hospital: Mostly video |

| GP: F2F | |||||

| P5U | 40s | F | Usual | Austin | Hospital: Mostly video |

| P6S | 50s | M | Shared | Austin | Hospital: F2F |

| GP: F2F | |||||

| P7U | 50s | M | Usual | Austin | Hospital: Phone/F2F |

| P8S | 50s | M | Shared | Austin | Hospital: Phone/F2F |

| GP: Phone/F2F | |||||

| P9U | 50s | F | Usual | PMCC | Hospital: Phone/F2F |

| P10U | 50s | F | Usual | PMCC | Hospital: Could not recall |

| P11S | 60s | M | Shared | PMCC | Hospital: Phone/F2F |

| GP: Phone/F2F | |||||

| P12S | 60s | F | Shared | PMCC | Hospital: Phone and/or video/F2F |

| GP: Phone and/or video/F2F | |||||

| P13U | 60s | M | Usual | PMCC | Hospital: Phone/video/F2F |

| P14S | 70s | M | Shared | PMCC | Hospital: F2F |

| GP: F2F | |||||

| P15S | 70s | M | Shared | Western | Hospital: Phone/F2F |

| GP: did not attend GP appointment | |||||

| P16U | 70s | M | Usual | Western | Hospital: F2F |

| P17S | 70s | M | Shared | Western | Hospital: F2F |

| GP: Phone/F2F | |||||

| P18U | 70s | M | Usual | RMH | Hospital: F2F/video |

| P19U | 80s | M | Usual | RMH | Hospital: Video/phone |

| P20U | 80s | F | Usual | RMH | Hospital: Phone/F2F |

- Abbreviations: F2F, Face-to-Face; PMCC, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre; RMH, Royal Melbourne Hospital.

- a To support anonymity.

Facilitators and barriers to shared care: Themes, categories (bold, outer circles) and codes (italics).

3.1 Facilitators and barriers to implementing shared care

Five themes were developed on the facilitators and barriers to implementing shared care as perceived by those who had experienced either 12 months of shared or usual survivorship care in the SCORE trial: communication with and between health care providers; relationships with GPs; accessibility of GPs; satisfaction with cancer treatment; and participant beliefs, attitudes and values. In data illustrations, participants P1S, P3S, P4S etc., received shared care, and P2U, P5U, P7U etc., received usual care.

3.2 Communication with and between health care providers

When I first went there, she didn’t even know why I was there. I explained to her, and she said ‘Oh, I know nothing about this…” It makes you a little bit nervous because you don’t want to miss out on any care that’s meant to be done. (P4S)

Alternatively, when they perceived good specialist-GP communication, participants were “more comfortable” (P10U) seeing GPs for follow-up care.

Participants also identified the need for clarity of roles between specialists and GPs, sometimes querying who was “the first port of call?” (P12S). They expressed confusion around appointment schedules and attributed this to poor hospital communication.

While some participants stated that informative resources helped clarify shared care expectations, few recalled receiving any information, or if they did, did not use them.

3.3 Relationships with GPs

Many described the advantages of having “good,” longstanding relationships with GPs, including feeling comfortable to “talk more freely,” (P10U) believing that the GP “really cares” (P17S) and that GPs can be trusted. Participant P10U detailed the benefits of being able to “explain in my language how I am feeling” when their GP is from the same cultural and linguistic background.

I may never go back to the (hospital) again, but if my GP knows what’s happened in those years, and what I had, what were the results… because I may follow my GP for a long time… she can understand all of what happened… I think she can help me in future. (P3S)

3.4 Accessibility of GPs

Participants found their GPs to be more geographically accessible and convenient, particularly those living rurally who had GPs in the same town, or “only 10 min down the road” (P11S). Some mentioned they could contact/see their GP more frequently and more urgently than oncologists if needed.

However, some participants had difficulty making GP appointments due to limited availability, or GP leave-taking and inability to find another. This increased distress about unmet needs. GP affordability was also cited as an access barrier when their GP visit was not fully covered by the Medicare rebate.

3.5 Satisfaction with cancer treatment

Participants from all hospital sites spoke positively about experiences of hospital-based care during cancer treatment, describing it as “excellent,” (P19U) and “terrific” (P11S). Some preferred continuity of care with the same hospital staff rather than GP involvement. Participants also asserted that specialists are experts and felt more confident in hospital-based follow-up care. P15S stated “I probably had every confidence in the hospital because I think they did a marvellous job [during treatment].”

3.6 Beliefs, attitudes, and values

Many participants believed GPs could not expertly manage their survivorship care (especially if they had delays in diagnosis). P10U said “It makes you feel better … Because he [oncologist] knows the treatment that I had. Yes, he is a specialist in cancer, not like a GP.” Some also believed that GPs were redundant in survivorship care, with participant P7U stating “I don't see why I would need the GP for this.”

Others referenced the importance of reducing hospital system pressures and believed GPs were well-positioned in the shared care model to provide test results and follow-up. P1S stated “I think you're probably not wanting to take up hospital resources with getting notification of results … If it's just for results like blood tests and stuff like that, the GP could do that.”

3.7 Perspectives on using telehealth-delivered health care

Four themes were developed on perspectives about using telehealth for survivorship care accessed through GPs and hospital-based specialists: telehealth was convenient and more comfortable; satisfaction with quality of care; associated challenges; and future preferences (Appendix 4).

3.8 Telehealth appointments were comfortable and convenient

Many participants felt more relaxed during telehealth appointments due to being more comfortable at home, and less aware of the doctor being busy. Some participants found telehealth appointments less confronting as they avoided hospital waiting rooms, which were described by one participant as “very tense” (P2U). Another stated, “not that I was worried, but you see other people and you think ‘what are they going through?’” (P5U). Most felt telehealth saved travel and hospital waiting times.

3.9 Satisfaction with quality of care

For many participants, unless they believed they required a physical examination, for example, they felt unwell, there was no perceptible difference in quality of care. P4S said, “I feel it's exactly the same really. At that point they are only following up the results of bloods and scans so, it's no different.” Participants spoke of being “able to communicate” (P5U) effectively via telehealth. They described their interactions as “personable” (P12S) and “exactly the same” [as face-to-face] (P11S).

3.10 Challenges of telehealth appointments

A few participants cited difficulty setting up video appointments, due to not having the technology or required knowledge. Some participants found telephone appointments “impersonal” (P8S) and rushed. Incidental social interactions in the hospital were also missed with telehealth appointments for example, visits to the wellness centre.

3.11 Future preferences

If I don’t feel well and I think I need to go in and be examined, then I have to go in. But if it’s for a result or a test or something that’s not urgent… just to let you know what’s happening, I prefer just a phone call. (P11S)

However, some still preferred to see their doctor face-to-face for ease of communication. P18U said, “If I want to see the doctor, I will go and see [them] in person… First of all, I haven't got a computer, that's one thing. Second, I've got poor hearing.”

4 DISCUSSION

CRC survivors who participated in a controlled shared care intervention discussed their experiences of survivorship care. The study results deepen our understanding of the facilitators and barriers to implementing shared care and allow recommendations to guide future implementation. Factors for consideration include communication, survivor beliefs and attitudes, relationships with GPs and preferences for telehealth-based care.

4.1 Communication

The shared care intervention followed a study protocol29 with defined roles for the GP and specialist. However, participants still expressed confusion about the follow-up schedule, and roles and responsibilities of each provider when the model of care was not specialist-led. Similar experiences have been reported in GP-led models of follow-up for CRC survivors.43 While participants in the shared care arm of the SCORE trial received SCPs to facilitate communication, many could not recall using these and still found that their GPs were unsure of the study protocol, leading to distress that their care needs were not being met. Better communication tools are needed between hospital-based care providers, GPs, and patients as shared care models have been deemed less acceptable when survivors perceived poor communication between care providers.18, 23 A survivorship care coordinator role may assist in the implementation of shared care by scheduling tests, following up results, sending appointment reminders, and serving as a point of contact and support for both patients and providers.24 Research suggests that GPs would prefer clear follow-up protocols and easy access to hospital-based specialist teams, rather than additional training to implement shared care.24 Electronic medical records that facilitate sharing of health information between GPs and specialists in real time might enhance the efficiency of communication.10

4.2 Survivor beliefs and attitudes

Consistent with existing literature, survivors in our study were often concerned about their GP's knowledge of cancer survivorship, and doubted their ability to provide effective survivorship care.16, 23 Some participants also believed that, because specialists are experts, GPs are not needed in survivorship care. This belief is incongruent with growing evidence which shows that GPs can play a vital role in survivorship care12, 15 and specialist-led models leave survivors with unmet needs.9-13 This inconsistency suggests there is a need to better: explain to patients the purpose of survivorship care and the roles of the GP and specialist (and survivorship care coordinator); prepare patients for alternative models of survivorship care; and reassure patients that shared care is a safe and appropriate alternative to specialist-led follow-up.9, 17

4.3 Relationships with GPs

Generally, participants who experienced shared care were satisfied with having their GP involved while remaining connected to their specialist. Emerging data from the SCORE trial show that CRC survivors exposed to shared care prefer this model.44 Studies suggest there is not a “one size fits all” model of survivorship care and recommend personalising care pathways based on individuals' risk of recurrence and long-term effects, existing physical and psychosocial issues, circumstances, and capacity to self-manage.9, 10, 24 We suggest including quality of the patient-GP relationship in this criteria, as this was found to be both a facilitator and barrier to shared care, depending on whether it was perceived to be “good” or “poor”. Similarly, Lisy et al24 found that patients having a regular, trusted GP was a facilitator to shared care. Personalised follow-up care pathways may lead to better patient outcomes with more efficient use of oncology time, fewer visits for survivors, and reduced overall costs.9

4.4 Telehealth-delivered care

Importantly, the results also suggest that when only receiving test results, survivors are satisfied with accessing survivorship care via telehealth (both telephone and video), and generally perceived no difference in quality of care received when attending these appointments in person or via telehealth. This finding is significant given the uptake of telehealth during and since the global COVID-19 pandemic, and the limited data on telehealth use in adult survivors of CRC.32 Telehealth-based follow up can create care environments at home, work or wherever is convenient for the survivor of cancer.34 It is recommended that patient preferences for telephone/video appointments versus in person be considered when offering a particular model of follow-up and, in line with Chan et al,32 that telehealth be offered to supplement in-person appointments and not as a stand-alone model of follow-up.

4.5 Study limitations

The results of this study should be interpreted in light of several limitations. Firstly, we explored perspectives of CRC survivors treated in the public health system in Melbourne, Australia. These results may not be generalisable to other cancer types, to people treated in the private system, or to other countries with different health care systems. Second, the study participants were interviewed at various time points, with some completing their participation in the SCORE trial more than 12 months before they were interviewed. This may have led to recall bias in interviews and accounted for difficulty recalling survivorship care resources and other aspects of their survivorship care. We also acknowledge the potential risk of selection bias with interviews of participants in the SCORE trial who had already agreed to being randomised to shared care, and may have more favourable attitudes towards GP involvement. Additionally, we only explored patient perspectives on their first 12 months of survivorship care, and not the longer-term acceptability of the model for example, at two, three, or five years-post treatment. It is possible that patient perspectives (including confidence in their GP) may change over time as GPs become more experienced in the provision of shared care. Cancer-specific issues and concerns might also be less prominent years later.

4.6 Clinical implications

- (1)

Personalise pathways of care based on individual characteristics, preferences, health care settings and existing relationships with their GP.

- (2)

Utilise a care coordinator and IT systems to facilitate use of SCPs, manage appointments and follow-up schedules.

- (3)

Provide direct lines of communication including shared electronic medical records between GPs and specialists.

- (4)

Prepare patients at the outset about pathways of survivorship care and the role of the GP in providing holistic health care.

It is also suggested that researchers and healthcare practitioners evaluate future implementation of shared care against implementation outcomes,26 as well as clinical and service outcomes.

5 CONCLUSION

Our study explored CRC survivors' perspectives on the facilitators and barriers to implementing alternative models of survivorship care, such as those delivered via telehealth and those that are shared between the GP and hospital-based specialist. Key themes included: communication with and between health care providers; relationships with GPs; satisfaction with cancer treatment; participant beliefs, attitudes, and values; and convenience and comfortability of alternative models of care. Findings can guide the implementation of these models, particularly around care coordination, communication, preparation, and personalised pathways of care.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge funding from the Victorian Cancer Agency (grant number HSR 15036) and from Cancer Australia (grant number 1158397). JDE is supported by an NHMRC Investigator grant APP1195302.

Open access publishing facilitated by Swinburne University of Technology, as part of the Wiley - Swinburne University of Technology agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

All authors of this article declare they have no conflicts of interest.

CLINICAL TRIAL REGISTRATION

The Shared Care for Colorectal Cancer (SCORE) Trial is registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry, ACTRN12617000004369p. Registered on 3 January 2017; protocol version 4 approved 24 February 2017.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.