The Effects of a Tier 1 Self-Regulation Intervention on Elementary Students’ Engagement and Reading Comprehension

ABSTRACT

As students’ emotional self-regulation impacts their engagement in learning, as well as their mental health, researchers have called for schools to implement systems of emotional support. However, because school resources are limited, and the demands on teachers’ time continue to grow, identifying emotional self-regulation interventions that teachers can easily implement within their classrooms can be beneficial for student well-being. This study examined the effects of a Tier 1 Self-Regulation Intervention on student engagement and reading comprehension. Within an A-B-A-B-A-B reversal design, a pilot self-regulation intervention was implemented in two classrooms over 6 weeks. The study's results indicated that the intervention may have positively impacted student engagement and reading comprehension. Given the study's positive results, the intervention may be a strategy to support student emotional regulation. Future researchers should consider the benefits of the intervention in larger social and behavioral schoolwide systems, such as MTSS.

Summary

-

Self-regulation skills help students to manage their attention, emotions, and behavior to engage in learning.

-

Teachers and schools may benefit from a brief Tier 1 Self-Regulation Intervention to support the engagement of students.

-

This study offers a Tier 1 Self-Regulation Intervention that was accepted by teachers and indicated improvement in student engagement and reading comprehension.

1 Introduction

Schools have an essential role in fostering the emotional development of students and supporting their mental health. Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic negatively affected student mental health due to social isolation, family economic hardships, fear of loss or illness, and reduced access to health care (Center for Disease and Control Prevention 2022). As student mental health concerns rise, policymakers have charged schools to implement multi-tiered systems (MTSS) to enhance emotional functioning and improve academic engagement (Center for Disease and Control Prevention 2022; Office of the Surgeon General 2022).

MTSS involves a continuum of interventions, including whole-school, universally applied Tier 1 interventions, that can improve behavioral, social, emotional, and academic outcomes. Further, when staff provide Tier 1 (i.e., universal, schoolwide) level support, there can be a positive impact on student mental health and behavioral outcomes, leading to improved emotional regulation and ability to learn (Clark et al. 2021; Immordino-Yang 2015). One form of MTSS involves the implementation of schoolwide social and emotional learning (SEL) programming to enhance student self-regulation.

2 Framing the Problem

Regrettably, school staff lack efficient strategies to embed schoolwide SEL strategies in their classrooms (Kern et al. 2022), often due to staff and funding shortages (Sutcher et al. 2019). Although teachers must focus on teaching academics while supporting the increasing emotional needs of students (Fonderen et al. 2020; Schonert-Reichl 2017), they do not receive adequate preparation and support to build the emotional development of students and feel unequipped to address students’ mental health needs. While this balancing act is difficult, supporting students’ emotional regulation may be critical to academic success. As such, teachers may benefit from brief, efficient, Tier 1 interventions that target skills to support emotions and increase engagement in learning.

2.1 Impact of Emotions on Engagement and Self-Regulation

Emotions shape not only what students learn but also how and why they engage with the material. When students experience positive emotions, they are more likely to participate actively, stay motivated, and achieve academic success. In contrast, negative emotions can lead to disengagement, avoidance, and diminished learning outcomes. Support and encouragement create an environment where students feel safe to think critically, express emotions, and engage both socially and intellectually (Hamedi et al. 2019; Immordino-Yang 2015; Goetz et al. 2006; MacCann et al. 2020). Beyond shaping motivation, emotions also influence essential cognitive functions, including attention, memory, complex thinking, and decision-making (Pekrun 2014). Because of this deep connection, students who develop emotional self-regulation skills may experience improvements not only in their social and behavioral development but also in their academic performance.

Self-regulation plays a key role in helping students manage their emotions, thoughts, and behaviors in ways that support learning and personal growth (Pekrun et al. 2002; Zimmerman 2002). Students who are able to regulate their emotions tend to be more resilient, proactive, and optimistic about their future (Zimmerman 2002). They are also better equipped to navigate challenges such as stress, anxiety, and trauma—factors that can interfere with concentration and learning. On the other hand, students who struggle with self-regulation may find it difficult to cope with frustration, manage stress, or develop the patience needed for academic tasks (Khan and Jameel 2024). These difficulties extend beyond behavior, affecting core academic skills such as reading comprehension. Given these connections, fostering emotional self-regulation is not just about well-being; it may be a critical component of academic success.

2.2 Reading Comprehension and Emotion

Reading comprehension requires readers to decode words, understand vocabulary, access prior knowledge, connect with background knowledge, make predictions, and construct meaning (Hamedi et al. 2019). These are complex learning skills developed over time through engagement in academic instruction. Student emotions toward reading directly affect the quantity and effectiveness of student engagement, which impacts reading performance (Grabe and Stoller 2019; Wigfield et al. 2004). Emotional regulation can significantly impact complex cognitive tasks, such as reading comprehension, which involves the combination of emotions, cognition, and behaviors (Fredricks et al. 2004; Grabe and Stoller 2019; Hamedi et al. 2019). Addressing the emotional needs of students may improve reading engagement and comprehension, which could lead to improved student success. Given the connection between emotions and reading comprehension, schools must adopt comprehensive strategies to support student engagement.

2.3 Interventions to Support Engagement and Reading Comprehension

A Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS) offers a framework designed to meet students’ social, emotional, academic, and behavioral needs across a continuum (Bohanon et al. 2024; Center on Multi-Tiered Systems of Support. 2023; Horner et al. 2017). The MTSS framework includes three tiers of instruction and support services, universal screening, implementation of researched intervention, and integrated data collection to inform decisions (Marlowe 2021). Tier 1 involves universal interventions for all students (e.g., effective core instruction, teaching expected behaviors, increased opportunities to respond; Kittleman et al. 2025). While typically schoolwide, Tier 1 interventions can also include applications to more broadly defined groups, such as classrooms. A primary goal of Tier 1 support is to reduce risk and maintain student health and safety (Cullinan 2022). By addressing Tier I prevention strategies, schools can create lasting academic, social, emotional, and behavioral improvement (Greenberg and Abenavoli, R 2017).

Tier 2 involves strategic support for 10–15% of students who do not adequately respond to Tier 1 interventions alone. These interventions (e.g., check-in and check-out, small academic skills groups) focus on students with minor problem behaviors or missing some academic-related skills needed for success (Kittleman et al. 2025). Tier 3 encompasses individualized interventions (e.g., functional behavior assessment, academic remediation, small social skills development) to address the intense needs of about 1–5% of the population (McIntosh and Goodman 2016; August et al. 2018). Tiers 2 and 3 are more time-intensive and require significantly more specialized training and resource demands. Due to the high percentage of students with mental health concerns, emotional support-based Tier 1 focusing on emotional support may provide an efficient first step for prevention.

Tier 1 systems for emotional support in the classroom can build consistency, safety, support, and positive interactions, which all students can benefit from regardless of their emotional readiness (Cavanaugh 2016). These emotional supports may include a structured SEL curriculum or clear classroom expectations with positive reinforcement. However, a brief Tier 1 intervention focused on emotional development can support teacher implementation while improving student development (Greenberg and Abenavoli, R 2017). By providing Tier 1 instruction to improve emotional development, students may be able to better engage in learning, specifically reading comprehension. One promising approach to supporting both emotional and academic growth at Tier 1 is the use of cognitive behavioral interventions.

2.4 Cognitive Behavioral Interventions

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is grounded in the idea that our cognitive processes, behaviors, and emotions are interconnected (Kalodner 2011). While therapists typically use CBT, school personnel can also implement cognitive behavioral interventions (CBI) to support students. When applied by teachers, students learn how their thoughts influence their emotions and, ultimately, their academic and social behaviors. When teachers integrate CBIs within an MTSS framework, students develop cognitive strategies that can decrease anxiety, fear, and aggression while improving peer relations and social cognition (Daunic et al. 2006). Common examples of CBIs include meditation, self-affirmation, positive reinforcement, and deep breathing. However, there is limited research on effectively embedding these interventions into Tier 1 instruction. To address this gap in the literature, the researchers in this study examined how a CBI could improve students’ self-regulation and in turn, engagement and reading comprehension.

3 Research Objective and Questions

The purpose of this study was to examine the impact of a universal Tier 1 Self-Regulation Intervention on student engagement and reading comprehension. The intervention was based on cognitive behavioral interventions (CBI) due to their potential to positively influence student emotions. Specific CBI strategies included focused breathing, self-affirmation, meditative listening, and emotion labeling. The researchers aimed to implement a brief and effective intervention that would enhance both student engagement and reading comprehension scores. In addition, the study assessed teacher satisfaction with the intervention training and its implementation. The intervention was designed to be adaptable across various grades, content areas, student readiness levels, and staff experience. The following were the research questions for the study.

RQ1..What were the effects of a 5-min classroom-based CBI intervention on students’ overall classroom engagement, as measured by a direct behavior rating (DBR) form?

RQ2..What was the impact of the intervention on reading comprehension, as measured by a curriculum-based Maze probe?

RQ3..After receiving training on the intervention, to what extent did teachers implement the intervention with fidelity (i.e., adherence to the procedures), as measured by an implementation fidelity checklist?

RQ4..After teachers receive training in the intervention, what was their perceived social validity of the intervention before and after implementation, as measured by the Intervention Rating Profile-15 (IRP-15)?

4 Methods

4.1 Setting

The study occurred in 2 classrooms in a Midwestern, urban, catholic school with 150 PK-8th Grade students. Among the student population, 95% of the student population identified as Hispanic, and 100% of the students qualified for free and reduced-price lunch. The study occurred during the school's 6-week school-based summer school program from the middle of June until the end of July, and included academic, athletic, and fine arts activities. The program was offered to all students attending the school and open to the community.

Due to the small number of students participating in the summer camp, there were only two classrooms for ages 7 to 12. All students in both classrooms participated in the Tier 1 Self-Regulation Intervention, which was immediately followed by a reading comprehension lesson. The reading lessons followed the Scholastic Guided Reading Program, which was an evidence-informed program to teach and improve reading comprehension (Pinnell and Fountas 2010). The Scholastic Guided Reading Program included scripted instructor plans and student books for each lesson, correlating with the students’ reading levels. The researchers adapted the lesson plans to fit within the 45-min instructional block for the summer school program, focusing on reading comprehension.

Before the study, the researcher trained the teachers in how to follow the scripted plans and use the student books to implement the reading lesson. The reading lesson was completed every day of the summer program. Lesson materials included researcher-developed intervention resources (e.g., script for the teacher), scripted reading lesson plans for teachers, and guided reading books for students.

4.2 Participants

All students in the summer camp participated in the intervention. However, data were only collected for students who attended the program consistently and for whom parental consent was obtained. Ultimately, the participants in this study included five students: Max, Zac, Ben, Pam, and Sam. To obtain pre-baseline information and examine the intervention's impact on participants who may be at behavioral and emotional risk, the Student Risk Screening Scale – Internalizing and Externalizing (SRSS-IE) (Lane and Menzies 2009) was completed by classroom teachers, before summer camp, for all students participating in summer camp. The SRSS-IE is a reliable and valid universal screener designed to identify students with signs of internalizing or externalizing behaviors such as shyness, anxiousness, aggression, or noncompliance. The risk level cut scores for SRSS-I are 0–1 = low risk, 2–3 moderate risk, and 4–15 = high risk. The risk level cut scores for the SRSS-E are 0–3 = low risk, 4–8 = moderate risk, and 9–21 = high risk. SRSS-I scores fell in the low risk range for Max, Zac, and Ben, and in the moderate risk range for Pam and Sam, while SRSS-E scores fell in the low risk range for Zac and Sam, in the moderate risk range for Ben and Pam, and in the high risk range for Max.

Approval to conduct this study was obtained from Loyola University Chicago's institutional review board (IRB). Approval was then obtained from the diocese and the school. Teachers and parents provided written consent. Student assent was received during their participation in summer camp, per the university-approved human subjects’ protocol.

4.3 Tier 1 Self-Regulation Intervention

Researchers designed the study's independent variable - a Tier 1 Self-Regulation Intervention, grounded in CBT and SEL strategies to increase the participants’ self-regulation. The intervention was based on the 10-Point Check-In intervention from the CBT Toolbox for Children and Adolescents (Phifer et al. 2017). The 10-point check-in supports grounding and coping skills, where students begin the intervention at step ten and then work their way down to step one. (10. Take 10 deep breaths, 9. Name 9 things you see, 8. Name 8 people who support you, etc.) It also includes students evaluating how they felt at the start and the end of this intervention. For this study, the 10-point check-in was modified to 5 steps: take 3 rounds of deep breath, identify 3 things that you hear, define 2 emotions you are feeling, make 1 compliment to yourself, and take 3 rounds of deep breath. The purpose of modifying the intervention was to develop a brief strategy for classroom teachers to utilize before starting a lesson or activity. The intervention was purposefully adapted to have minimal materials so that students and teachers could transfer this intervention easily and quickly to various settings.

The intervention included CBI and SEL strategies of meditative breathing, meditative listening, self-awareness, and self-affirmation. The teachers conducted the 5-min intervention during treatment weeks immediately before the reading lesson. Teachers were provided a guide to walk students through meditative breathing and listening, self-affirmation, and self-awareness. An example from this guide related to meditative listening is, “We are going to listen to the sounds in our school. Begin by finding the first sound. Focus on this sound and take a deep breath (pause for 10 s.) Let's find a new sound and focus on it. Take a deep breath while focusing on that sound (pause for 10 s.) Find one last sound and take a deep breath while focusing on that sound.” A poster in the classroom displayed the treatment steps as a visual prompt for student participation in the intervention.

4.4 Dependent Variables

The researchers evaluated the effects of the Tier 1 Self-Regulation Intervention on student engagement and reading comprehension.

4.4.1 Student Engagement

Student engagement was defined by the student's level of academic engagement, respectful behavior, and disruptive behavior during a reading comprehension lesson. Academic engagement was defined as actively or passively participating in the classroom activity. Respectful behavior was defined as compliant and polite behavior in response to adults and peers. Disruptive behavior was defined as student action that interrupts classroom activities (Direct Behavior Rating DBR Form: 3 Standard Behaviors. 2009). A measure of overall engagement was calculated by averaging the scores within each baseline and intervention phase.

4.4.2 Reading Comprehension

Reading comprehension was defined by the student's ability to construct meaning of a text by using a variety of reading skills including decoding, fluency, vocabulary, and motivation (Wright 2013).

4.5 Measures

4.5.1 Direct Behavior Rating (DBR) Form

Teachers completed a DBR form to measure student engagement (Chafouleas et al. 2010). A DBR form is an evidence-based scale that can be used to monitor an intervention's effectiveness (University of Connecticut 2010). The DBR form included 3 areas: academically engaged behavior, respectful behavior, and disruptive behavior. Each area was scored on a scale from 0 to 10, with 0 meaning the behavior was present 0% of the time, and 10 meaning the behavior was present 100% of the time during the reading lesson.

The teachers completed the DBR form for each student immediately following the reading lesson. Teachers rated their perception of the student's behavior during the reading lesson. The DBR form was used to measure if the intervention impacted engagement by comparing DBR ratings between baseline and intervention.

The researchers conducted interobserver agreement observations during 33% of the study sessions to assess the reliability of data collection for student engagement. The acceptable range for interobserver agreement is typically between 70% and 80% (Artman et al. 2012). The lead researcher's DBR score was compared to the teacher's DBR score for each student to calculate interobserver agreement. A DBR score was agreed upon if the researcher and teacher rated the engagement within 2 numbers above or below on the scale. The mean interobserver score for the study was 86%, meaning the researcher and teacher's DBR scores agreed 86% of the time. These results indicate that the DBR was a reliable measure of student engagement.

4.5.2 Maze CBM Probes

The teachers administered a curriculum-based measurement (CBMs) Maze assessment once per week to each student participant to measure reading comprehension (Curriculum-based measurement Maze passage 2007). CBM assessments are a reliable and valid measure to assess progress of reading comprehension and make formative decisions to support students (Fuchs and Fuchs 2002; Hosp and Suchey 2014). The assessment is a short passage where the first sentence is written completely, and every seventh word following the first sentence is to be correctly chosen. The Maze assessments for the study were created through Intervention Central, using passages from the Scholastic Guided Reading Program that were aligned with students’ reading levels. Students completed a Maze assessment at the end of each week as a measure of intervention effectiveness. To administer the Maze assessment, each student received the assessment on paper and a writing utensil to answer the question. The students had 3 min to complete the assessment. The scores for each student were calculated by dividing the number correctly answered over the total number of questions.

4.5.3 Design

A single case A-B-A-B-A-B withdrawal design (Kazdin 2021) was used to evaluate the effects of the intervention on student engagement and reading comprehension. During the baseline condition, students did not receive the Tier 1 Self-Regulation Intervention, and during the intervention condition, students received the Tier 1 Self-Regulation Intervention each day of camp, immediately before the day's reading lesson. Each baseline and intervention period lasted for 1 week.

4.6 Procedures

The lead researcher trained the participating teachers on all study components. The training took place in 1 meeting session and included providing teachers with all materials and explaining how to utilize each material. This included the Tier 1 Self-Regulation Intervention, reading lesson, DBR form, note taking, Maze assessment, and the daily fidelity checklist. The lead researcher also provided the baseline IRP-15 survey to the teachers before the study to provide feedback on acceptability of the intervention.

During baseline weeks, the teachers implemented the reading lesson daily and completed the DBR form for each student after the reading lesson. Students completed the Maze assessment at the end of each week. During intervention weeks, the teachers implemented the Tier 1 Self-Regulation Intervention daily, followed by the reading lesson. The teachers completed the DBR form for each student after the reading lesson, and the Maze assessment was completed at the end of each week. Teachers also had the option to write specific notes on the DBR form about student engagement during baseline and treatment weeks. At the completion of the study, the teachers completed the IRP-15 survey again to provide feedback on acceptability of the intervention after implementation.

Table 1 shows the specific procedures of the baseline and intervention weeks.

| Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline/nontreatment week | Reading lesson DBR form |

Reading lesson DBR form Researcher fidelity check |

Reading lesson Maze assessment DBR form Teacher notes on DBR form |

| Intervention week | Intervention Reading lesson DBR form |

Intervention Reading lesson DBR form Researcher fidelity check |

Intervention Reading lesson Maze assessment DBR form Teacher notes on DBR form |

- Note: Students attended the enrichment program three days per week.

4.7 Implementation Fidelity

The degree to which teachers implemented the Tier 1 Self-Regulation Intervention with fidelity was measured by an implementation fidelity checklist (Horner et al. 2006). The checklist included each step of the intervention, and teachers indicated which steps of the intervention they completed each time it was implemented. The researcher conducted observations of the intervention in practice during 33% of the study sessions. Checklists were scored to calculate the percentage of steps and the percentage of steps in which teachers adhered to intervention procedures.

4.8 Social Validity

Teachers who implemented the intervention completed the Intervention Rating Profile-15 (IRP-15) (Witt and Elliott 1985) before and after the study as a measure of social validity. The IRP-15 was administered before and after the study to examine if the teacher perception changed after implementation. The survey contains fifteen questions on a six-point Likert scale used to determine the acceptability of an intervention (Martens et al. 1985). Response options range from strongly disagree to strongly agree. A higher rating on the rating continuum indicates a higher level of acceptability. The range for the total score for the IRP-15 is between 15 and 90 points. A moderate level of treatment acceptability for a total score is 52.5 and above (Ozdemir 2008). The tool also has strong internal consistency (α = 0.98; Martens et al. 1985).

4.9 Data Analysis

DBR and CBM data were analyzed by visual inspection (Kazden 2021). Visual inspection included an examination of changes to level, trend, and variability. The IRP-15 survey was analyzed by reviewing the total score to determine acceptability and calculating the percent of change from pre and post observation score.

5 Results

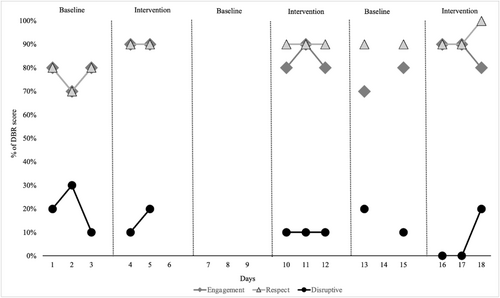

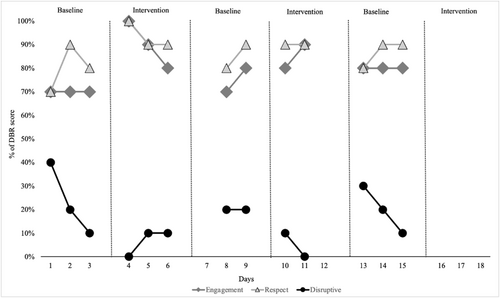

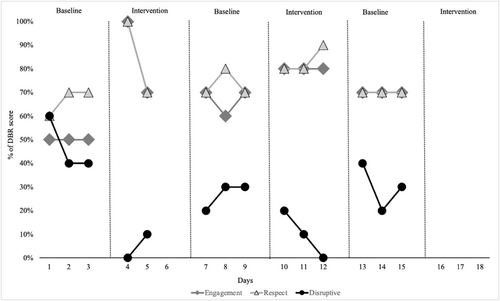

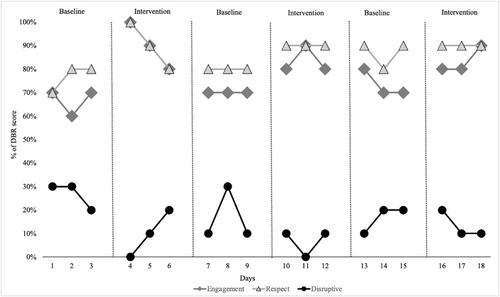

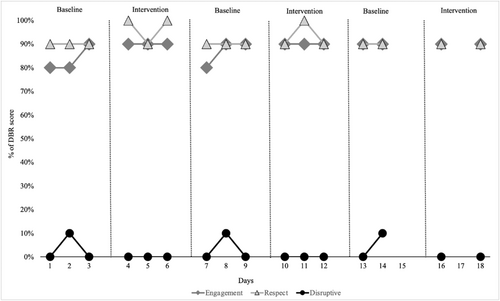

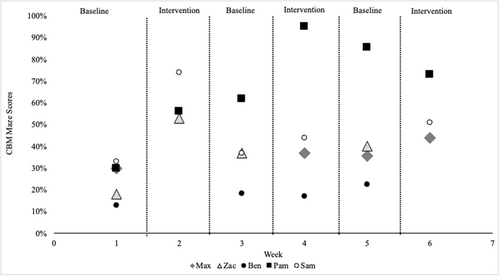

The following sections include the results based on the study's RQ's. To review specific student scores, review Figures 1-5. Max, Zac, and Ben are missing certain study phases due to absence from summer camp.

5.1 Student Engagement

5.1.1 Academic Engagement

The individual weekly mean academic engagement scores, as measured by DBRs, were higher during intervention weeks. The overall weekly mean scores were higher during intervention weeks and increased from 70% in Week 1% to 88% in Week 6. The most significant participant increase was with Pam whose average baseline weeks scores were 67%, 70%, and 73% and her average intervention weeks were 90%, 87%, and 87%. Additionally, the overall weekly mean standard deviation scores were lower during intervention weeks, indicating less variability between scores. Table 2 shows the average weekly academic engagement scores for each student participant, along with the overall weekly mean score and weekly standard deviation.

| Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Week 5 | Week 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max | 77% | 90% | Absent | 87% | 75% | 87% |

| Zac | 70% | 90% | 75% | 85% | 80% | Absent |

| Ben | 50% | 85% | 67% | 80% | 70% | Absent |

| Pam | 67% | 90% | 70% | 87% | 73% | 87% |

| Sam | 87% | 90% | 87% | 90% | 90% | 90% |

| Weekly Mean Score | 70% | 89% | 74% | 86% | 76% | 88% |

| Weekly Standard Deviation | 0.136638 | 0.022361 | 0.088081 | 0.037014 | 0.078294 | 0.017321 |

5.1.2 Respectful Behavior

The individual weekly mean respectful scores, as measured by DBRs, were equal or higher during intervention weeks. The overall weekly mean scores were higher during intervention weeks and increased from 78% in Week 1% to 90% in Week 6. The most significant participant increase was with Pam whose average baseline weeks scores were 77%, 80%, and 87% and her average intervention weeks were 90% every week. The overall weekly mean standard deviation scores were also lower during intervention weeks, indicating less variability between scores. It should be noted that although the results indicate a moderate positive effect for some participants, the general effect was minimal. For example (201)'s initial score was 77% and maintained a score of 90% from Week 2 to Week 6. Table 3 shows the average weekly respectful behavior scores for each student participant, along with the overall weekly mean score and weekly standard deviation.

| Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Week 5 | Week 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max | 77% | 90% | Absent | 90% | 90% | 90% |

| Zac | 80% | 93% | 85% | 90% | 87% | Absent |

| Ben | 67% | 85% | 73% | 83% | 70% | Absent |

| Pam | 77% | 90% | 80% | 90% | 87% | 90% |

| Sam | 90% | 97% | 93% | 93% | 90% | 90% |

| Weekly Mean Score | 78% | 91% | 83% | 89% | 85% | 90% |

| Weekly Standard Deviation | 0.08228 | 0.044159 | 0.084212 | 0.037014 | 0.084083 | 0 |

5.1.3 Disruptive Behavior

The individual weekly mean disruptive scores, as measured by DBRs, were lower during intervention weeks. The overall weekly mean scores were higher during intervention weeks and decreased from 24% in Week 1% to 7% in Week 6. The most significant participant decrease was with Ben, whose average baseline weeks scores were 47%, 27%, and 30% and his average intervention weeks were 5% and 10% (Ben was absent the last week). Further, the overall weekly mean standard deviation scores were lower during intervention weeks (see Figures 1-5), indicating less variability between scores. Table 4 shows the average weekly disruptive behavior scores for each student participant, along with the overall weekly mean score and weekly standard deviation.

| Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Week 5 | Week 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max | 20% | 15% | Absent | 10% | 15% | 7% |

| Zac | 23% | 7% | 20% | 5% | 20% | Absent |

| Ben | 47% | 5% | 27% | 10% | 30% | Absent |

| Pam | 27% | 10% | 17% | 7% | 17% | 13% |

| Sam | 3% | 0% | 3% | 0% | 5% | 0% |

| Weekly Mean Score | 24% | 7% | 17% | 6% | 17% | 7% |

| Weekly Standard Deviation | 0.15779 | 0.055946 | 0.100789 | 0.041593 | 0.090167 | 0.065064 |

The following Figures 1-5 provide daily DBR scores for each student participant.

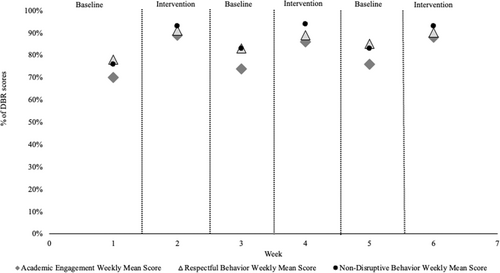

5.1.4 Overall Engagement

Figure 6 includes the weekly overall mean score for all DBR categories (i.e., academic engagement, respectful behavior, and nondisruptive behavior) and the average scores for baseline and intervention weeks. Based on these data, all participants’ engagement appeared to be higher during the intervention weeks. In all cases, the overall mean standard deviation intervention scores were lower or equal to baseline study phases, indicating less or equal variability during the intervention.

5.2 Reading Comprehension

RQ2 involved measuring the impact of the intervention on reading comprehension, based on weekly Maze probes. All student participants improved their reading comprehension scores from week one to week six (see Figure 7). As shown in Figure 7, the overall weekly mean participant score improved from 25% to 56% across the study phases. The most significant improvements took place between week one (baseline) and week two (intervention) when the mean score changed from 25% to 61%. In most instances, reading scores were higher during intervention weeks than baseline, with two exceptions. Ben started with and sustained the lowest comprehension scores, was absent for 2 of the tests, and had a higher week three (baseline) than week four (intervention). Pam had a higher score in week five (baseline) than week six (intervention).

5.3 Intervention Fidelity

Teachers completed an implementation fidelity checklist each time they implemented the intervention. Results indicated 100% implementation fidelity, meaning all interventions were implemented with fidelity. Additionally, the inter-rater agreement was 100%, indicating that the teachers self-assessed their implementation fidelity reliably.

5.4 Social Validity

Teachers completed the IRP-15 (add citation) before and after the study to provide a measure of their perceptions of efficiency and acceptability. The pre-intervention score for Teacher 1 was 60 and Teacher 2 was 80. The post-observation score for Teacher 1 was 73 and Teacher 2 was 83. The scores indicate that teacher perceptions of the intervention before and following implementation were above the acceptable range (Ozdemir 2008). Qualitatively, one teacher stated the intervention was, “[a] great strategy to calm students down and get them focused before a lesson.” These results indicated that teachers found the intervention to be efficient and acceptable.

6 Discussion

The purpose of this study was to determine the impact of a Tier 1 Self-Regulation Intervention on student engagement and reading comprehension. Based on the single-case experimental design, the researcher's interpretation of the results indicated that in general, students’ engagement and reading comprehension scores were higher during treatment weeks. Also, all students improved their overall reading comprehension. The following section includes a discussion of results based on student engagement, reading comprehension, and teacher implementation.

6.1 Student Engagement

The five participants displayed increased classroom engagement as measured by the DBR between baseline and intervention weeks. The following section includes a discussion of the results of the three components of the DBR: (a) academic engagement, (b) respectful behavior, and (c) disruptive behavior.

6.1.1 Academic Engagement

While all students showed improvement in academic engagement, Ben had the largest improvement between baselines. Ben also had the second highest risk factor based on the SRSS-IE (i.e., internalized behaviors). No student returned to the same or below week one baseline levels of academic engagement. These outcomes may result from the maintained treatment effect during nontreatment weeks. These results also appear to support the connection between academic engagement and self-regulation (Pekrun et al. 2002).

6.1.2 Respectful Behavior

Although the weekly mean respectful scores indicate a moderate positive effect for some participants, the general effect was minimal. However, no student dropped below week one baseline levels of respectful behavior. As with previous research, student self-regulation in this study may be connected to improved desired behaviors, such as respect (Duckworth and Carlson 2013; Wolters and Brady 2020).

6.1.3 Disruptive Behavior

Most students had lower levels of disruptive behavior in every phase of the study compared to their week one baseline data. This finding may result from maintained treatment effect across the study phases. Sam maintained a low disruptive score throughout the study; therefore, there was less potential for a change in the rating score. Interestingly, Zac had a large drop in disruptive behavior between baseline and intervention weeks. This student also had the lowest SRSS-IE score, suggesting that students not identified as at-risk may also benefit from the intervention. Students with higher risk levels for internalized behavior may still struggle at some level with self-regulation, which manifests in disrupted behaviors (Khan and Jameel 2024). Still, these results support how self-regulation skills can assist all students in managing their behavior to engage in learning (Wolters and Brady 2020).

6.1.4 Overall Engagement

The overall weekly mean score never returned to the same or below week one baseline levels of overall engagement. The engagement data further supported how a universal self-regulation intervention could build a classroom environment that supports students’ engagement and the individualized needs of students (Cavanaugh 2016). The results also supported the idea that emotional regulation can positively impact a student's engagement (Immordino-Yang, 2015). The DBR was an indirect measure of the students’ ability to self-regulate. While it is not known if the student's emotional regulation improved, it appears the participants controlled their attention as measured by academic engagement. Additionally, their behavioral impulses and disruptive behavior patterns improved. Hence, the intervention shows promise towards addressing components of self-regulation (Duckworth and Carlson 2013; Khan and Jameel 2024; Wolters and Brady 2020).

6.2 Reading Comprehension

As with previous research (Hamedi et al. 2019; Fredricks et al. 2004), the researchers found that emotional regulation may impact a student's reading comprehension. In terms of reading, all five participants displayed increased reading comprehension as measured by the Maze probe from week one to week six. Also, the students’ mean comprehension scores were higher during intervention weeks and lower during baseline weeks. The scores indicate that the intervention may have impacted the reading comprehension scores. These results connect to previous research, which suggests that a student's ability to engage in reading is based on a combination of emotional, cognitive, and behavioral factors (Fredricks et al. 2004; Khan and Jameel 2024). As previously stated, emotional readiness is critical for students to successfully engage in the complexities of reading comprehension (Wigfield et al. 2004; Grabe and Stoller 2019). The Maze assessment results align with research that social and emotional skills are associated with better school performance, including reading comprehension.

The increase in comprehension scores was gradual and fluctuated for each student. For example, Pam's scores started at 30% in week one and ended at 73% in week six, but scores in weeks two and six fluctuated. Also, Ben's baseline reading scores improved between week one and five, however, they decreased during week four which was an intervention week. Reading comprehension scores improved through the research process, but the individual student results did not show exact improvement on weeks that included the intervention. Also, there was more variability in the weekly mean standard deviation patterns across the study phases. These results may indicate that students with lower reading performance levels may take longer to improve in their comprehension skills. It is unclear from the individual student participants’ data if the improvement was due to the intervention or the weekly reading lesson. However, there are sufficient data to show that the intervention may have been a catalyst for reading comprehension improvement within this study, as shown by the overall comprehension score improvement during intervention weeks related to DBR scores.

The interpretation of these results suggests that helping students regulate and modify their emotions through an intervention can have positive outcomes, such as academic success. The study's results support the connection between emotions and reading comprehension (Khan and Jameel 2024). Based on the researchers’ interpretation of these results, there may be an association between emotional regulation and how effectively students learn to read (Wigfield and Guthrie 1997; Wigfield et al. 2004).

6.3 Students Identified as At-Risk

Before the start of the study, school-year teachers completed an SRSS-IE to determine if any students within the study were at emotional or behavioral risk. Max, Ben, Pam, and Sam received SRSS-IE scores indicating levels of risk. In terms of gains, Max and Pam's DBR and CBM assessment scores increased from Week 1 to Week 6. These improvements included higher scores during intervention weeks. Ben's overall DBR and CBM assessment scores improved from Week 1 to 5. However, this student was absent for Week 6 of the study. The data's upward trend provides hope for continued improvement for this student. Overall, the results from this study indicate that the intervention was an effective method to support the classroom engagement and reading comprehension of students with and without identified emotional or behavioral risk factors. Given the students with greater levels of risk improved during the study, the intervention may be an effective process to address, in part, the rising need to address student mental health (Office of the Surgeon General 2022).

6.4 Teacher Implementation: Fidelity and Social Validity

The fidelity checklist data was 100% for all items related to the intervention, suggesting that the teachers implemented the intervention with fidelity across all phases of the study. These data support that future teachers may be able to implement a CBI-related intervention with fidelity if it is brief, efficient, and requires limited training. The fidelity checks can also serve as an opportunity for coaches or administrators to provide feedback and training to teachers on their implementation.

Additionally, the social validity data suggests teachers would be interested in using the intervention to improve student engagement and reading comprehension. The post-intervention mean score was 78, which was above the reported moderate level of treatment acceptability for the IPR-15 (Ozdemir 2008). The study outcomes indicate that teachers in this study found it to be acceptable, meaning that other teachers may be willing to utilize this intervention. As a result, teachers might efficiently use the intervention individually and universally with all classroom students (Bohanon et al. 2024; Center on Multi-Tiered Systems of Support. 2023).

This intervention may also benefit schools and teachers whose staff lack training and knowledge in emotional development. A brief Tier 1 intervention, such as the one in this study, could help teachers feel better equipped to help students’ emotional regulation (Schonert-Reichl 2017). A brief intervention may be needed due to minimal formal training or professional development about the impact of trauma and ways to respond (Fonderen et al. 2020).

6.5 Limitations

Readers should consider the study's limitations when interpreting the results. One key limitation was that student participants attended a voluntary summer school program, which may not reflect typical school-year conditions. To enhance generalizability, future research should examine student data collected during the traditional academic year. Additionally, the study was constrained by a small sample size and the limited duration of the 6-week summer program. Replicating the study with larger participant groups over an extended period and across diverse educational settings would strengthen the findings.

Another limitation involved the number of teacher participants. With a limited pool of educators, the generalizability of the social validity data was restricted. Future studies should explore increased sample sizes with greater diversity in teacher experience, age groups, and instructional settings. Expanding the number of educators implementing the intervention could also provide further insights into its effectiveness and applicability. Despite this, the Tier 1 Self-Regulation Intervention was found to be acceptable for the teachers involved in the study. Collecting additional qualitative feedback from teachers and students could refine the intervention and enhance its social validity in future research.

While the study suggests that the Tier 1 Self-Regulation Intervention may improve student engagement and comprehension, further research is needed to determine which aspects of the procedure contributed to these positive outcomes. For example, it remains unclear whether improvements in student comprehension resulted from the daily guided reading lessons, the self-regulation intervention, or a combination of both. Implementing research designs with greater experimental rigor, such as quasi-experimental studies, could help isolate the intervention's specific effects.

Additionally, although students’ emotional and behavioral risk levels were assessed before the study using the SRSS-IE, post-intervention scores were not collected. Future research should include follow-up assessments and longitudinal probe data to evaluate the long-term impact of the intervention on students’ emotional and behavioral outcomes. Moreover, while the researchers monitored the fidelity of the emotional regulation intervention, they did not track the fidelity of the reading intervention. Future studies should incorporate both aspects to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the study's impact.

Finally, while the participating school had components of an academic MTSS model in place, it did not implement MTSS for behavior or social-emotional learning. Future research should explore how the study's Tier 1 strategy might function within a broader schoolwide system that integrates both academic and behavioral supports.

7 Significance of the Study and Conclusion

Teachers need brief and effective interventions that benefit student emotional regulation. This need is due to growing mental health concerns and the resulting demands placed on teachers. Given the study's positive results, the intervention may be an additional Tier 1 strategy for staff to support student emotional regulation. The intervention appeared to be associated with higher levels of comprehension, lower levels of perceived classroom disruption, higher levels of perceived student engagement, and high levels of fidelity and social validity for teachers. Educators may value study's improved student engagement and academic outcomes. MTSS leadership teams might consider self-regulation strategies as part of their Tier 1 core approaches to student support. While more research is needed, students with and without identified risk factors could potentially benefit from these interventions. Educators may also find these approaches acceptable if embedded within their instruction. Future research should consider class-wide units of analysis as one step towards scaling the intervention toward schoolwide application.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Christina Culver, M.Ed. and Dr. Laura Riffle, Ph.D. for their feedback on the development of this manuscript.

Ethics Statement

Human subjects' approval was obtained from Loyola University Chicago.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Preprint Source

Reichart. (2023). Measuring the Effect of an Intervention on Student Engagement and Reading Comprehension. Doctoral dissertation, Loyola University Chicago.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Data is available by request to the author.