Diabetes service provision in primary care: a baseline survey in a city primary care trust (PCT)

Abstract

Primary care trusts (PCTs) are a key plank of the modernisation of the NHS in the UK. They have a unique role in the commissioning and provision of services to local communities. A baseline assessment of diabetes service provision in primary care is vital in establishing current levels of service and in developing service models relevant to local populations. We have developed and evaluated an audit tool to baseline diabetes services in primary care. We used this tool in the Eastern Leicester PCT which serves a population of 180 000 with a high South Asian population, estimated to be around 50%. This PCT has a high number of single-handed general practices serving a deprived population. The survey was undertaken using direct interviewing of key members of the primary health care team, using a semi-structured interview lasting for around an hour. All practices in the PCT were involved. The results of this survey highlighted major deficiencies in current services, e.g. only 10% of the practices had a structured plan for providing education for people with diabetes. It also demonstrated how regional estimates of the prevalence of diabetes in the UK may seriously underestimate the ‘true’ prevalence in some localities. This study highlights the uphill task many PCTs will face in terms of meeting the national service framework standards and providing basic elements of diabetes care. Copyright © 2004 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is one of the most common chronic diseases in the world. Around 4% of the current world population is estimated to have type 2 diabetes, with a projected increase of over 120% between 1994 and 2025; this translates to an increase of 135 million, to over 300 million people.1 This rapid rise is due to a number of factors including reduction in physical activity, increase in obesity and the concept of epidemiological transition.2-4

The increase in the incidence of type 2 diabetes is predominantly amongst the older population, but is occurring in all age groups and is more and more affecting children and young people. In the UK those at particular risk are the South Asian population where reported rates are at least four times higher than in white Caucasians.5

It is therefore very timely that diabetes has become a national health priority in England with the recently published National Service Framework (NSF)-for Diabetes standards and delivery strategy.6, 7

Primary care trusts (PCTs) are an important feature of the modernisation of the NHS in the UK. 8 Given their unique role in the commissioning and provision of services to local communities, PCTs will be central to the delivery of diabetes care and the implementation of the NSF for Diabetes.7

One of the key initial steps in the delivery strategy for the NSF is to review the local baseline assessment at a primary care level. Indeed, this baseline assessment of diabetes service provision in primary care is vital in establishing current levels of services and in informing resource allocation and service model development issues relevant to specific PCT populations. Such information will enable PCTs to demonstrate progress in the implementation of the NSF, including the reduction in variation of service quality – an issue highlighted by the Audit Commis-sion report.9

Leicestershire currently has a population of over 950 000 of a mixed culture and rural character. Approximately one third (320 000) are resident in the city of Leicester, which includes areas of substantial material deprivation. The proportion of the Leicester city population from ethnic minority backgrounds is five times the average for England and Wales (28% versus 6% at the 1991 census). This comprises mainly people of South Asian origin (24%), with the Eastern part of the city having rates of 50%. We know that people of South Asian ethnic background are at particularly high risk of both type 2 diabetes and its complications.10 Leicestershire South Asians have been recently shown to have acute coronary heart disease rates twice as high as those of the Caucasian population.11

Eastern Leicester PCT serves a population of 180 000 with a high South Asian population (estimated at 50%). The PCT has a high number of single-handed general practices serving a deprived population.

Previous problems within the PCT have highlighted issues such as poor development of primary health care teams and lack of resources. The PCT at an early stage has identified diabetes as one of its clinical priorities. We report the first part of a baseline survey looking at current service provision for diabetes in primary care within the trust.

Patients and methods

The baseline assessment was undertaken by the direct interview of key members of the primary health care team involved in practice diabetes service provision. A trained diabetes specialist nurse with a primary care background interviewed one or more of the lead general practitioners (GPs), lead practice nurse or practice manager in each practice. The interview schedule was previously tested and refined in a number of practices in the Coventry area and adjusted to the needs of Eastern Leicester PCT (ELPCT). Each practice was initially informed of the purpose of the study by the PCT clinical governance lead by letter, and the interviewer subsequently telephoned the practice to arrange an appointment.

A semi-structured interview technique was used with data entered on to a written template. Each interview lasted at least an hour and where possible documented evidence of standards of service were requested (e.g. the evidence of an up-to-date diabetes register or a practice protocol). Table 1 documents the key topics covered in the interview.

| Diabetes register present | Time allocated for ‘annual review’ and follow-up |

| Estimated number of people with diabetes | Care of housebound people with diabetes |

| Dedicated diabetes clinic in practice | Participation in clinical audit |

| Practice nurse hours | Practice equipment |

| Diabetes training undertaken by practice staff | Practice protocols |

| Education provided to people with diabetes | Access to support for diabetes care (e.g. dietician, podiatry, secondary care) |

| Practice initiation of insulin therapy |

Results

We present key findings of the practice interviews particularly relevant to the development of diabetes services in the PCT.

In terms of the personnel interviewed, 33 practices (100% of the PCT practices) were interviewed in total with the lead nurse and GP interviewed in 20 (60.6%) practices. In the remainder, one or the other of these individuals was interviewed; in two (6%) practices the practice manager only was interviewed. The interview data were analysed by the interviewer and the PCT clinical governance lead and key issues for the PCT highlighted in a report.

Ten (30%) practices had a diabetes register, which appeared to be regularly updated and used for diabetes care (e.g. call and re-call). A further 10 (30%) practices claimed only an up-to-date register. In all, 10 (30%) practices had a register but this was not maintained and was likely to be inaccurate and incomplete. Three (10%) practices had no register at all.

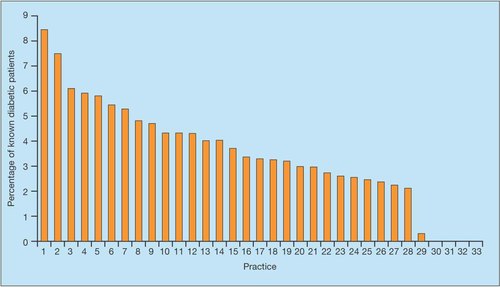

In all, from a reported 188 052 subjects registered across the PCT, 6895 were reported as having diabetes – a prevalence of 3.6%. Three practices reported a prevalence of diabetes of over 6%, 11 practices had a prevalence of 4–5.9%, 14 practices had a prevalence of 2–3.9%, and one practice had a prevalence of less than 0.35%. Four practices had no data on prevalence. (See Figure 1).

Estimated percentage of patients with diabetes per practice

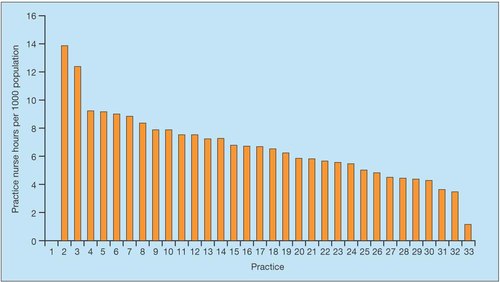

In terms of dedicated diabetes clinics in practices, 14 (42%) practices ran clinics of which 10 were nurse-led, one GP-led and three joint-led (GP and nurse). However, there was a large variation in total practice nurse hours between practices. Two (6%) practices had over 10 hours of practice nurse time per 1000 patients on their list per week, 16 (48%) practices had six to nine hours, and 15 (45%) practices had less than six hours, with one of these having only one hour per 1000 patients per week. One practice had no nurse hours. (See Figure 2).

Total hours of practice nurse time per 1000 patients per week

In terms of training, 13 (39%) of practices had a practice nurse who had completed an ‘accredited training course’ for diabetes (such as the Warwick and Bradford course), with a further 13 having attended local updates only. Only one practice (3%) had a GP who had attended an accredited course, with only three having attended local updates on diabetes.

Only three (10%) practices claimed that they had a structured plan in providing education for people with diabetes, which included dedicated sessions for education and minimum standards of patient information.

Regarding the care of housebound people with diabetes, 26 (79%) practices reported that annual reviews were carried out by only the district nursing staff, only one (3%) practice had documentation of district nurse training for this role and only four (12%) practices had a practice protocol for district nurse use.

Bearing in mind that Leicester-shire has an active primary care audit group with a national reputation in primary care audit of diabetes care, it was disappointing that only 15 (45%) practices had undertaken a clinical audit in diabetes care within the previous three years.12, 13

Regarding the issue of availability of diabetes equipment at the surgery, the presence of calibrated glucose meters was variable with 16 (48%) practices having these. Only two (6%) practices had monofilaments for testing for neuropathy. No practices routinely tested for microalbuminuria either in the premises or via the hospital laboratory. Screening for retinopathy was also highly variable with a mixture of practice, optician and hospital screening used. Time allocated for annual review and follow-up appointment varied and is summarised in Table 2.

| Time allocated | Annual review | Follow-up visit |

|---|---|---|

| 30 minutes | 6 (18%) | 2 (6%) |

| 20 minutes | 14 (42%) | 10 (30%) |

| 15 minutes | 7 (20%) | 5 (15%) |

| 10 minutes | 6 (18%) | 14 (42%) |

| 5 minutes | 0 | 2 (6%) |

Practices in general had access to dieticians and podiatry but reported long waiting lists – sometimes of several months. Use of secondary care varied from use for only type 1 diabetes, to referral of all patients in one practice.

Twenty-three (76%) practices were unable to produce a practice protocol for diabetes; the remainder had protocols of various types (practice, local or national). Only three (10%) practices felt they had the skills and time to initiate insulin for people with diabetes.

Discussion

Other groups have published on methods of assessing health care needs in a primary care setting. Some have concentrated very much at a PCT level and have used various models to predict prevalence and therefore the potential costs of diabetes services but have not addressed some of the more qualitative issues.14

Other surveys have comprised self-reported questionnaire studies and generally have reported far higher levels of service provision than in our study.15 For example, Pierce et al. reported 80% practices having diabetes registers and 85% of practice nurses claiming to have undertaken training.15 Our survey demonstrated that either the ELPCT has much lower levels of service provision compared to elsewhere or that self-reported national data are misleading with over-reporting or over-optimistic interpretation of practice service provision.

This study highlights the uphill task that many PCTs may face in terms of meeting the NSF standards. Standard 4 relating to ‘clinical care of diabetes’ states ‘the presence of accurate up-to-date diabetes registers is a corner stone of organising care at practice level’. Clearly, even this basic requirement is not in place in many practices in ELPCT. The importance of this is obvious, as studies have clearly demonstrated that good quality care in general practice is dependent on well-organised and systematic service delivery.16

Even more worrying is that the effective implementation of Standard 3 ‘Empowering people with diabetes’ requires that people with diabetes receive ‘structured education’ to improve knowledge to enhance self-care. ELPCT is far from this position with only three (10%) practices feeling they offer such education.

This study emphasises the difficulties that primary care faces in providing even basic elements of diabetes care – for example, it highlights an insufficient and inequitable distribution of practice nurse hours, and a huge training need for GPs, nurses and district staff. Even basic requirements – for example, practice protocols, ready access to support services such as dieticians and practice equipment – are problematic for many practices. Such shortfalls in the structural aspects of diabetes care compound poor teamwork – a feature of general practices which offer poor quality diabetic care. 17 To illustrate this further the inequity of care provided to housebound people with diabetes has been well documented in Leicestershire; this survey shows that poor training of district nurses and lack of team working to protocols may well contribute to this.18

The study gives a glimpse of the massive workload facing some city PCTs with a high ethnic population. The best organised practices with good registers reported prevalence rates of over 6% in our PCT and, even with incomplete databases (three practices provided no data at all), this survey still identified 6895 people with diabetes within the PCT. ELPCT in reality probably has some 12 000 people with diabetes – a huge issue in terms of resource and health need. This is of major concern as the Trent Observatory figures estimated a crude prevalence of 4.3% of diabetes in Leicestershire, and these figures may be used to plan services for the future. If these estimates are not adjusted upwards,19 this may lead to gross under resourcing of diabetes services, not only in Leicester but across the whole of the Trent region.

This baseline survey has put the implementation of the NSF for Diabetes in context for our PCT and – together with the clinical audit data (for both process and outcome indicators) that we are now collecting – will enable us to develop and implement realistic programmes for service improvement and development. An immediate result of this piece of work is that ELPCT, having recognised diabetes as a priority area, has invested in additional specialist diabetes resource, which has been particularly targeted to the 12 most ‘needy’ practices, identified through this baseline assessment.

Whilst ELPCT serves a deprived and largely ethnic population, its needs are by no means unique and should serve to warn that without such baseline data PCTs will seriously underestimate the needs of both the primary health care teams and populations they serve. The resulting inability to meet the aspirations of the NSF for Diabetes may then seriously damage the proposed role of primary care being pivotal in the provision of a decent service for people with diabetes.

Key points

-

Primary care trusts may face an uphill task in meeting NSF standards

-

The presence of up-to-date diabetes registers is a basic requirement that is not present in many practices

-

Many practices feel they don't provide structured education to patients, making the effective implementation of Standard 3 of the NSF ‘Empowering people with diabetes’ difficult to achieve

-

Primary care faces difficulties in providing even basic elements of diabetes care